The Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities (DLUHC) held a consultation on social housing rents between 31 August and 12 October 2022. The consultation sought views on the introduction of a rent ceiling from 1 April 2023 to 31 March 2024. Our response to the consultation questions can be found below.

About the Local Government Association (LGA)

The LGA is the national voice of local government. We are a politically-led, cross party membership organisation, representing councils from England and Wales.

Our role is to support, promote and improve local government, and raise national awareness of the work of councils. Our ultimate ambition is to support councils to deliver local solutions to national problems.

LGA response to the consultation questions

Question 1: Do you agree that the maximum social housing rent increase from 1 April 2023 to 31 March 2024 should be subject to a specific ceiling in addition to the existing CPI +1 per cent limit? To what extent would Registered Providers be likely to increase rents in that year if the Government did not impose a specific ceiling?

We do not agree that the maximum social housing rent increase from 1 April 2023–31 March 2024 should be subject to a nationally-set lower ceiling to the existing Consumer Price Index (CPI) +1 per cent limit.

Councils are rightly very concerned about the impact that rising living costs are having on social housing residents across the country. With that in mind, councils had already been considering their approach to next year’s rents to ensure that a careful balance is made between affordability for tenants and investment in the homes that they live in. All councils we have had direct discussions with, as well as those who have been engaged in the Savills research described below, have confirmed that they were already planning for lower rent increases than CPI +1 per cent. Councils will also continue to do what they can to protect people from hardship, targeting help at people facing the most complex and acute challenges.

However, decisions on the level of rent increases need to continue to be made by councils within the existing government rent policy commitment of CPI +1 per cent limit. This will ensure that the variation in cost pressures for different local authorities can be taken into account at a local level and councils can determine the minimum rent increase necessary to meet committed expenditure requirements and essential and urgent new works, whilst balancing this with affordability for tenants.

There are a number of causes for variation in cost pressures across local authorities. These include:

- pay award inflation – while a fixed cash increase equivalent this will vary as a percentage pay increase to different local authorities given the pay base for each authority

- requirements to refinance existing debt and/or take on new debt – with costs going up as interest rates rise sharply

- levels of investment needed to maintain the decency of existing homes as well as undertake essential building safety work, especially with inflationary drivers above the long-term OBR forecast, for example, supplies and materials costs, contractor costs and construction costs

- levels of investment needed to raise the standard of all local authority homes to EPC Band C by 2030, paving the way for full decarbonisation by 2050.

It is also worth noting that 60 per cent of households renting homes from local authorities receive housing benefit and therefore will not benefit from a limit on rent increase in any case as their benefits will be increased in line with any increase.

Therefore, we consider that the proposal for a nationally-set rent restriction below CPI +1 per cent for all local authorities is an untargeted blunt approach which will have potential long-term and wide-ranging impacts on their ability to provide critical services for their tenants and invest in new and existing homes.

Notwithstanding our view that the maximum social housing rent increase from 1 April 2023–31 March 2024 should not be subject to a nationally-set lower ceiling than the existing CPI +1 per cent limit, if the Government does take forward a lower ceiling, 7 per cent should be the absolute minimum cap. This is the higher of the three proposed options in the consultation (3 per cent, 5 per cent or 7 per cent).

Alongside this, the Government should provide a suitable mechanism to mitigate for any shortfall in any local authority income from a lower rent ceiling e.g. through additional funding for 2023/24 (and future years) and / or a mechanism to allow ‘catch-up’ of lost income so that local authorities can continue to safeguard services and meet the country’s future housing needs.

As an example, the consultation impact assessment points out there will be a substantial reduction in government welfare spending if a rent restriction is taken forward (a £4.6 billion monetised benefit in the 5 per cent cap scenario) – this is money which could be used to support provision of services that tenants will otherwise not receive, because of the loss of income in local authorities resulting from a new ceiling on rents, as well as support for vital investment in new and existing stock.

More broadly, the future sustainability of Housing Revenue Accounts (HRA) remains a concern for stock-holding local authorities. The self-financing settlement in 2012 distributed debt to stock-holding local authorities on the assumption that anticipated rent income would be sufficient to fund works to raise all homes to Decent Homes Standard (DHS) and maintain them there, and to pay off debt over a 30-year period. That is, the settlement was calculated to ensure a level of debt that could be sustained having taken into account future income less future costs. The future costs included allowances for management, repairs and major repairs. Whilst the major repairs was allowance was significantly uprated, it was only ever intended to meet and maintain the Decent Homes Standard – based on the safety standards at the time. The settlement is now 10 years old, and its underlying income and expenditure assumptions have both been superseded. There was no allowance in the settlement for enhanced capital or revenue standards, for example it did not include all the additional enhanced fire and building safety works that local authorities are now required to undertake. Local authorities are therefore carrying a higher level of debt than they would have done had these additional requirements been taken into account. Put another way, rents are now being required to finance works that they were never intended to in 2012.

The 2012 settlement assumed HRA income based on annual rent increases of RPI +0.5 per cent, plus an allowance for convergence to formula rents where this had not yet have achieved. This assumption was compromised by Government decisions to scrap convergence and to reduce rents by 1 per cent a year for four years from April 2016, which resulted in an estimated 12 per cent reduction in average rents by 2020/21.

Current Government policy limits increases in rents to the Consumer Price Index (CPI) +1 per cent until 2025, however the current consultation which is proposing further rent restrictions adds another level of uncertainty and further compromises the successful delivery of HRA business plans and services to tenants.

Question 2: Do you agree with imposing a ceiling of 5 per cent, or are there alternative percentages that would be preferable, such as a 3 per cent or 7 per cent ceiling? Do you have any comments or evidence about the potential impact of different options, including of the 3 per cent, 5 per cent and 7 per cent options as assessed in our Impact Assessment (Annex D)?

As described in question 1, we do not agree with imposing any specific lower national rent ceiling on rents in addition to the existing CPI +1 per cent limit. Notwithstanding our view, if the Government does take forward a lower ceiling, 7 per cent should be the absolute minimum cap. Alongside this, the government should provide a suitable mechanism to mitigate for any shortfall in any local authority income from a lower rent ceiling, for example, through additional funding for 2023/24 (and future years) and/or a mechanism to allow ‘catch-up’ of lost income so that local authorities can continue to safeguard services and meet the country’s future housing needs.

The LGA, the National Federation of ALMOs (NFA) and the Association of Retained Council Housing (ARCH) have commissioned Savills to undertake analysis of the implications of a variety of rent scenarios from 2023/24, taking into account the context of current inflationary drivers on expenditure. The full Savills report is available on request.

This has resulted in a nationwide HRA projection based on several approaches to rent increases, as follows:

- baseline with rents CPI +1 per cent all years

- baseline with rents capped at 5 per cent for 2 years, no catch-up

- baseline with rents capped at 5 per cent for 2 years, with catch-up

- baseline with rents capped at 7 per cent for 2 years, with catch-up.

Implications of the modelled rent increases

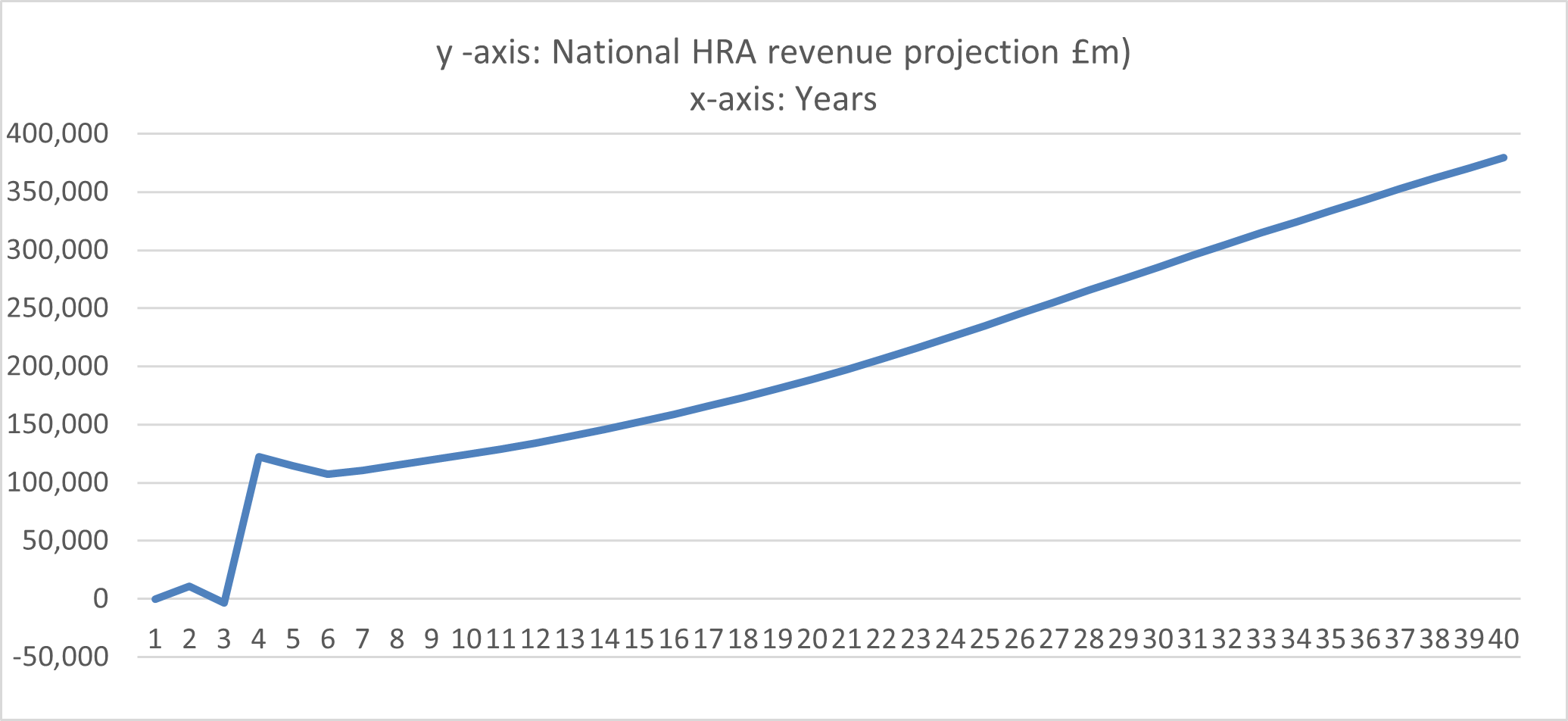

1. Rents CPI +1 per cent all years

Rent increases are as follows:

- April 2023: 11 per cent

- April 2024: 7 per cent

- April 2025: 5 per cent

- April 2026+: 3 per cent.

The chart below shows that in the first year or two, there are potential pressures on revenue arising even when rents are increased at the full CPI +1 per cent, because of the inflationary drivers in the HRA.

Beyond the first two to three years, however, the projection is for a gradually increasing relative annual surplus – which is entirely in line with expectations. Income and expenditure inflation have been aligned for all future years of the projection.

This 'steady state' projection offers the basis for comparison when rent increases are varied.

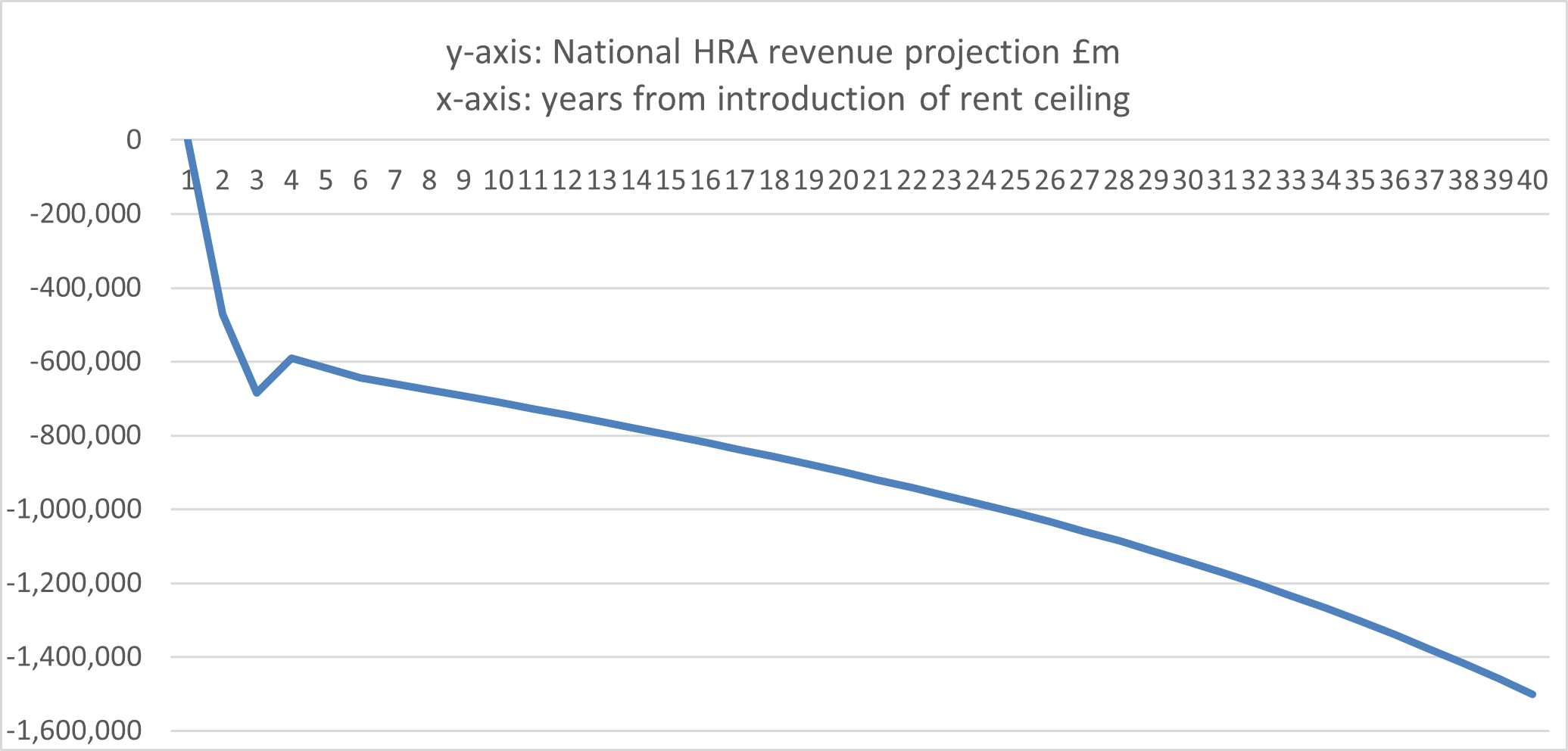

2. Rents capped at 5 per cent for 2 years, no catch-up

Rent increases are as follows:

- April 2023: 5 per cent

- April 2024: 5 per cent

- April 2025: 5 per cent

- April 2026+: 3 per cent.

The chart below shows that, in the first year or two, there is a risk of large deficits as rent increases do not keep up with cost inflationary pressures. This would need to be addressed by making substantial additional savings and/or using reserves

Beyond the first two to three years, the position is unable to be recovered as rents do not thereafter catch up with the cost pressures that have become part of the expenditure in the first two to three years.

This longer-term projection is therefore for increasing deficits: operating margins decline from around 18 per cent now to zero over the projection term. Operating margin is gross income less operating costs – before any financing or interest costs. It is the underlying operating margin that provides the surplus funds out of which local authorities can either borrow against, repay debt, or fund capital expenditure directly.

Cumulative loss of resources:

- 2 years: £1.16 billion

- 5 years: £3.36 billion

- 40 years: £45 billion.

These losses represent 6 to 8 per cent of all operating costs (including major repairs) or 9 to 11 per cent of management and maintenance costs.

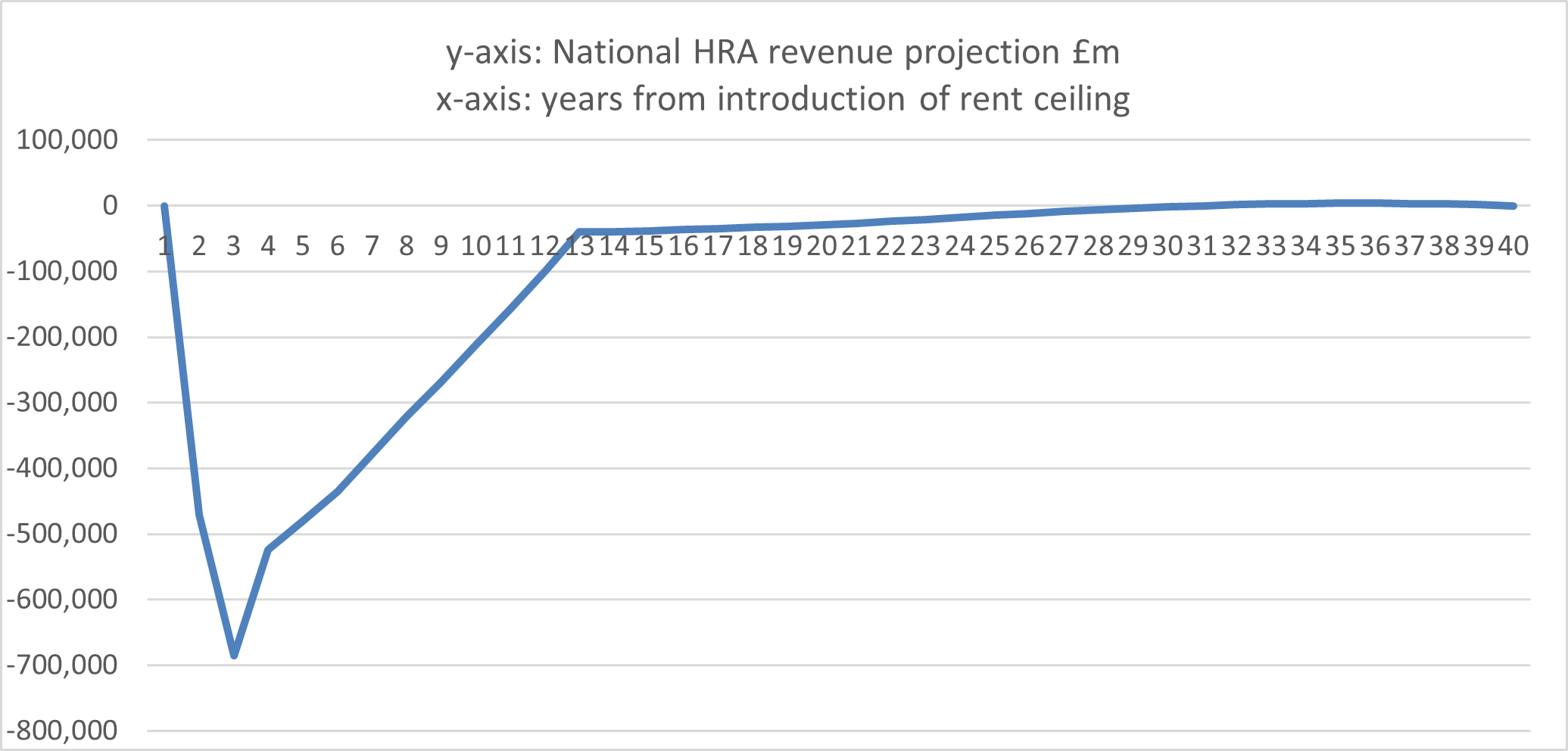

3. Rents capped at 5 per cent for 2 years, with catch-up over 10 years

Rent increases are as follows:

- April 2023: 5 per cent

- April 2024: 5 per cent

- April 2025/29: 4.1 per cent average

- April 2030/34: 3.5 per cent average

- April 2035+: 3 per cent average.

Cumulative loss of resources:

- 2 years: £1.16 billion

- 5 years: £2.95 billion

- 40 years: £12 billion.

These losses represent 5 to 7 per cent of all operating costs (including major repairs) or 8 to 10 per cent of management and maintenance costs in the first 2 to 3 years.

The chart below shows that in the first year or two, there is a risk of large deficits as rent increases do not keep up with cost inflationary pressures. This would need to be addressed by making substantial additional savings and/or using reserves.

Beyond the first two to three years, the position is able to be recovered as rents are gradually allowed to be increased back up to the original path of CPI +1 per cent.

If 'catch-up' is over 10 years, the projection position is to return to 'balance'.

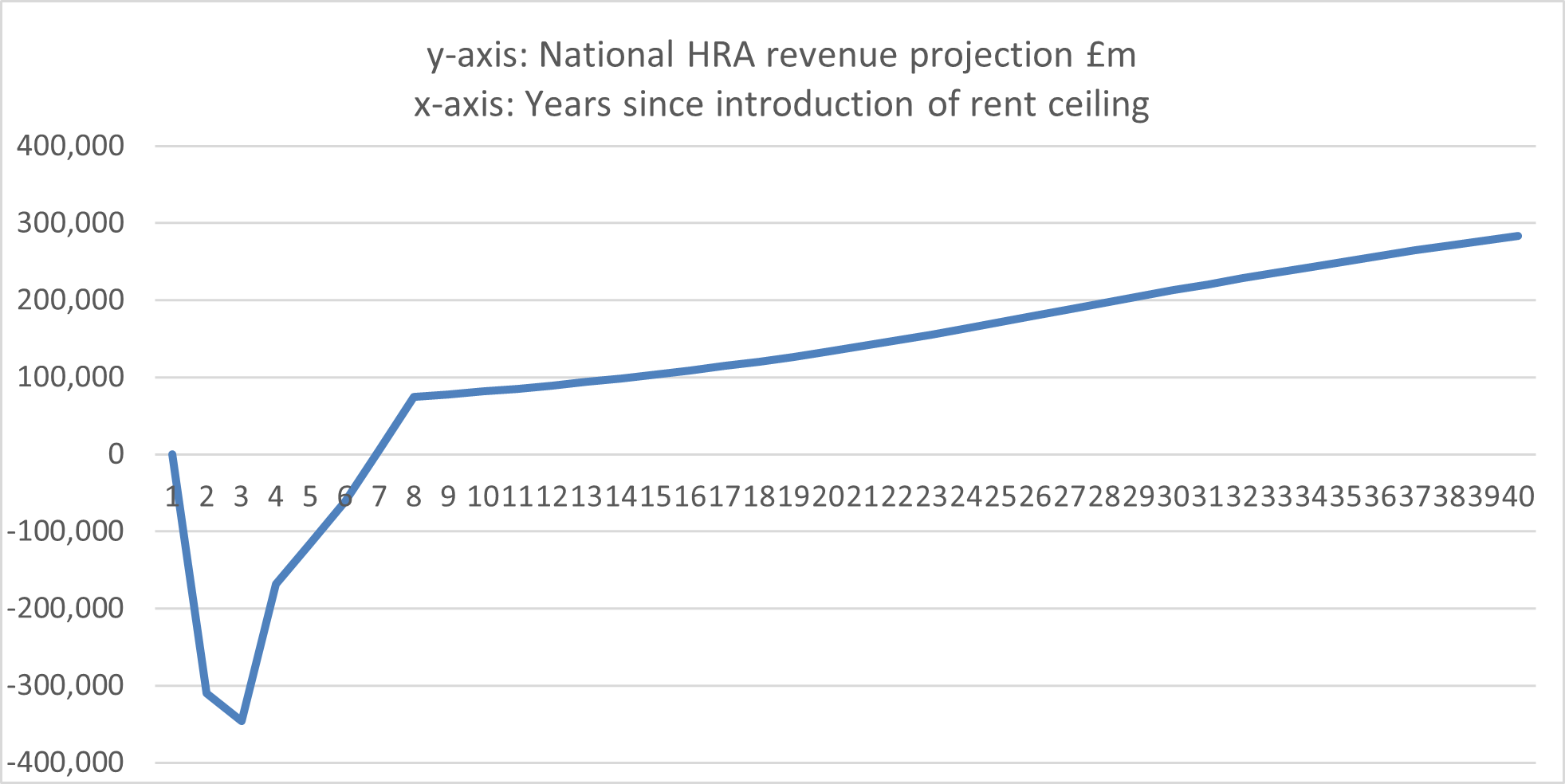

4. Rents capped at 7 per cent for 2 years, with catch-up over 10 years

Rent increases are as follows:

- April 2023: 7 per cent

- April 2024: 7 per cent

- April 2025/29: 4.1 per cent average

- April 2030/34: 3 per cent average

- April 2035+: 3 per cent.

Cumulative loss of resources:

- 2 years: £0.66 billion

- 5 years: £1.35 billion

- 40 years: £3 to 4 billion.

The chart below shows that in the first year or two, there is a risk of deficits as rent increases do not keep up with cost inflationary pressures. This would need to be addressed by making substantial additional savings and/or using reserves.

Beyond the first two to three years, the position is able to be recovered as rents are allowed to be increased back up to the original path of CPI +1 per cent.

If 'catch-up' is over 10 years, the projection position is to return to 'balance'.

Impact of rent decisions on individual local authorities housing management services and stock investment

The charts above illustrate the impact of a variety of rent approaches on HRA projections at a national level. Individual local authority responses to the consultation will also provide a local flavour of impact as this will be felt differently in different places based on a variety of factors, as outlined earlier.

We have also included a few examples below:

Example 1

If the rent increase is capped at 5 per cent, then this would result in a £1.9 million loss for a district council in the Eastern region, compared to a CPI +1 per cent increase. This is set against a context of the impact of inflation on the cost of delivering current services – as an illustration this is affecting their newbuild programme. In terms of acquisitions of new properties, prices between October 2021 and September 2022 have increased by around 20 per cent per square metre. In regards to the ongoing maintenance of existing homes, repairs are costed annually on a price per property basis and also expect to see an inflationary increase when these are reviewed for 2023/24. Any impact on increased costs above the inflationary baseline may impact on capital improvements, such as meeting net zero targets.

Example 2

The Government's proposed rent cap will bring additional serious financial challenges and disruption to the existing financial plans of a district council in the East Midlands.

The council’s capital programme assumes the acquisition or build of at least 40 new energy efficient homes. The programme of stock condition surveys being undertaken this year is also enabling them to accurately prepare their future investment programmes for new kitchens, bathrooms and other capital investment projects for 2023 onwards.

The investment proposed in the Housing Capital Programme will make a significant contribution to ensure the council’s housing stock is improved to increase its Standard Assessment Procedure (SAP) ratings and ensure all homes are efficient and provide affordable warmth for our tenants. The four-year capital programme to 2025/26 is currently £83 million: £54 million for major repairs and energy efficiency measures, £1 million for external wall insulation, £11 million for environmental works, £12 million for new build and £4 million for acquisitions.

There are already financial challenges and disruption to the council’s HRA resulting from the pandemic - due to loss of income in the form of rent arrears and increase in voids, as well as other increased costs, for example, personal protective equipment (PPE). The proposed rent cap will compound these further and will require savings to be made to reduce costs and comes at a time when residents are also under pressure with the cost of living.

The impact of a rent cap over the next two years would see:

- planned maintenance programmes lengthened, and major works delayed

- decarbonisation works put on hold

- new build and acquisitions falling dramatically – at a time when homelessness is rising and the number of households on the council waiting list has increased by 13.5 per cent in 2021/22 to 2558

- sharp decline in reserves

- additional borrowing with increasing interest costs.

Example 3

The impact of a rent increase ceiling of 5 per cent would result in a minimum of £11 million in lost income to the HRA for a metropolitan authority in the Yorkshire and Humber region. This would come at a time when they are facing steep increases in energy prices and costs as a result of the level of inflation. This is not just a one off but a compound impact and will seriously impact the HRA’s ability to invest in and maintain its current stock, also growth in terms of building new social housing and will severely impact the level of services provided to tenants.

Furthermore, the 2016/20 rent reduction policy is estimated to have cost the council over £300 million in lost income, with the council not compensated for lost income. While this cap will not have the same scale of effect, it will undoubtedly limit the councils HRA ambitions which will be to the detriment of tenants.

Possible policy solutions

Notwithstanding our view that there should not be a new lower rent ceiling in addition to the CPI +1 per cent limit, if the government is minded to introduce one, there are a number of options that the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities and the Treasury could take forward with local authorities to mitigate the impact, not least given the £4.6 billion monetised benefit for he Treasury in the 5 per cent rent cap scenario. These are not mutually exclusive and in addition should also be considered even in the absence of the introduction a nationally-set lower ceiling:

'Catch-up' mechanism

As described above, the Government should commit to a mechanism to allow ‘catch-up’ of lost income over a number of years. The Savills modelling looks at a 10-year catch up, but this could be reduced to two or five years for example, although this would of course mean higher rents for tenants over a shorter period of time. The catch-up mechanism could also be expanded to allow for the loss of rents that resulted from the government’s 2016/20 rent reduction programme.

Temporary revenue support

One off grants paid to local authority Housing Revenue Accounts as revenue support to cover spikes in inflation – there is a precedent with COVID-19 grants paid to local authorities to support increases in costs or loss of income.

Capital grant support

While not addressing challenges in the HRA directly, provision of additional capital support to cover fire and building safety, energy efficiency measures (EPC C by 2030) and revisions to the Decent Homes Standard would reduce pressures to divert revenue to cover these essential costs at a time when net revenue risks being permanently reduced. This would provide a mechanism which would help to ensure that these works are sustainably financed in HRAs.

Right to buy reform

Enabling councils to retain 100 per cent of receipts from Right to Buy sales and giving full flexibility on the use of receipts would support councils to deliver replacement homes more efficiently.

Public Works Loan Board (PWLB) borrowing rates

Rates had, at the time of the Savills research, increased to 3.5 to 3.7 per cent for long-term debt. While these rates remain below the long-term average interest rate in the Savills projection, a temporary reduction of these rates to lower the cost of investment in building safety and new build would maintain incentives for investment at a time when revenue budgets are under heavy pressure.

There could be two levels of input:

- A reduction on rates for all new borrowing (but not affecting refinancing). While it is difficult to model an extensive degree of support – assuming 4,000 new homes per annum at £250K build cost, 70 per cent leverage at 4 per cent interest cost would be £25 to 30 million. This would assist, but not prevent the need for other areas of savings / cuts.

- A general reduction in rates across the board.

Homes England Affordable Homes Programme

Local authorities continue to want to play a role in delivering additional homes through new-build programmes. But these are being hit by rising construction costs – this is affecting both materials and labour. A rent restriction as proposed in the consultation, will further compound this issue and make it even more difficult to fund the costs of new-build programmes. In light of this, Homes England should take action to review grant contributions to help sustain these programmes.

Social Housing Decarbonisation Fund

The Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) has recently launched the bidding round for Wave 2.1 of the Social Housing Decarbonisation Fund which is an important fund in terms of delivering improved energy performance for council homes, and in turn reducing tenants’ energy consumption and therefore outgoings – this is increasingly important in the context of the current high cost of energy. Decarbonisation is also vital to improving the comfort, health and well-being of tenants through the delivery of these warmer and more energy-efficient homes. In Wave 1 applicants were required to contribute at least a third of total eligible costs. Wave 2.1 now requires applicants to contribute a greater proportion of total eligible costs – 50 per cent. Any nationally-set lower rent ceiling below CPI+1 per cent, alongside recent price increases is going to make it increasingly difficult for local authorities to provide higher levels of matched funding. BEIS should urgently review and revise its assumed costs per dwelling alongside reviewing the required level of contribution from local authorities.

Housing Benefit and Universal Credit (UC)

The Housing Benefit uprate should be fully implemented and overall benefit / Universal Credit increased to minimise pressures on spending. This will be particularly important for those on partial benefit.

Question 3: Do you agree that the ceiling should only apply to social housing rent increases from 1 April 2023 to 31 March 2024, or do you think it should apply for two years (that is, up to 31 March 2025)?

Notwithstanding our view that there should not be a new lower rent ceiling in addition to the CPI+1 per cent limit, if the government is minded to introduce one, this should only apply for one year. This should be accompanied by a firm commitment that the rent ceiling will revert back to CPI+1 per cent in 2024/25. The Government should also commit to a suitable mechanism to mitigate for any shortfall in local authority income.

As described above, this could be through additional funding for 2023/24 (and future years) and/or a mechanism to allow ‘catch-up’ of lost income so that local authorities can continue to safeguard services and meet the country’s future housing needs.

Question 4: Do you agree that the proposed ceiling should not apply to the maximum initial rent that may be charged when Social Rent and Affordable Rent properties are first let and subsequently re-let?

Yes, notwithstanding our view that there should not be a new lower rent ceiling in addition to the CPI +1 per cent limit, exempting Social Rent and Affordable Rent properties when they are first let and subsequently re-let from any new ceiling that is introduced will allow some catch-up from loss of income.

Allowing homes to be let for the first time or re-let at formula rent, which has been increased by the full CPI +1 per cent, would help to stem a move into further deficit as described in some of the modelling scenarios outlined in response to Question 2.

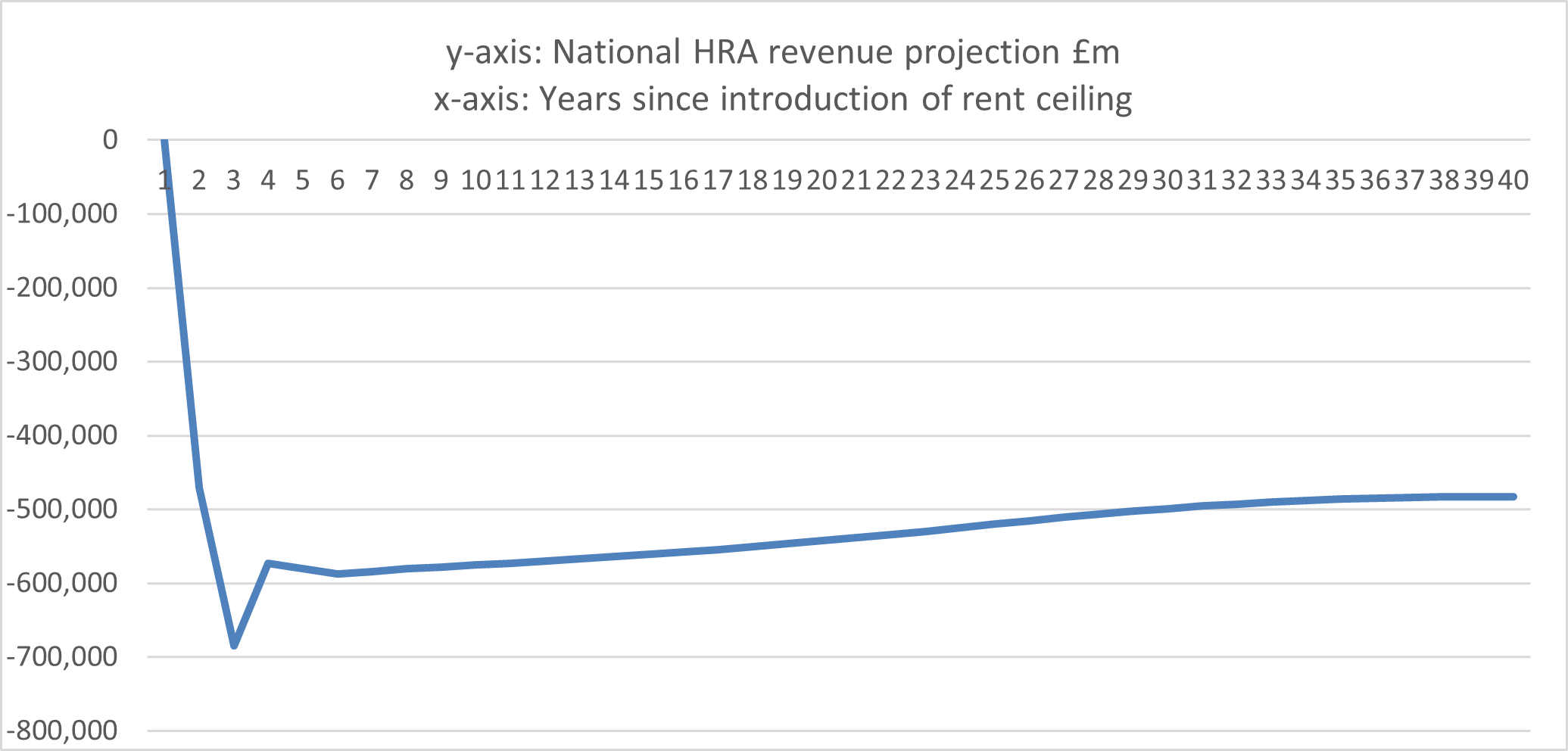

However, the Savills research estimates that not all stock would turnover in 40 years, with their estimate of relets being approximately 75 per cent of stock over that period. As the graph below shows, this mechanism would therefore not be sufficient to support recovery to formula rent at a level sufficient enough to return HRAs to surplus.

Savills estimates of the cumulative loss of resources resulting from a rent cap of 5 per cent with catch-up via re-lets only is:

2 years: £1.16 billion

5 years: £3.25 billion

40 years: £29 billion.

Question 5: We are not proposing to make exceptions for particular categories of rented social housing. Do you think any such exceptions should apply and what are your arguments / evidence for this?

Notwithstanding our view that there should not be a new lower rent ceiling in addition to the CPI +1 per cent limit, it is recognised that there may be some circumstances where the introduction of one could put the financial viability of a local authority Housing Revenue Account (HRA) at risk.

Therefore, should the Government be minded to introduce a new lower rent ceiling, we do not consider that there should be a blanket exception for particular categories of rented social housing. As the consultation points out, an individual housing provider will still be able to apply for an exemption, or the disapplication of the revised Rent Standard, as per the processes under the current Rent Standard.

Despite this mechanism being in place as an important safeguard for individual Registered Providers, the government should however be aware, that any lower rent ceiling, even if it does not jeopardise overall financial viability of individual HRAs, will still have an impact on local authorities and their tenants. This is because it will mean, as the consultation rightly recognises, that local authorities will have less money to invest in provision of new homes, improve the quality and energy efficiency or existing stock and provision of services to their tenants.

LGA, ARCH, NFA Rent and income analysis

To support our response to this consultation, we have used data from the research and analysis commissioned by the LGA on the rent and income capacity of Housing Revenue Accounts.

Note to users: this PDF is not fully accessible to WCAG 2.1 AA