Executive summary

There are nine sections in this briefing. The briefing can be read as a whole or readers can select the parts of most interest to them. The ‘Introduction’ outlines the background to this briefing, the second on adult safeguarding and homelessness. It identifies the diverse sources of knowledge that have been brought together to further enhance the evidence-base for working with people experiencing multiple exclusion homelessness. The focus is very much on learning for sector-led improvement. Particular emphasis is given to learning from those with lived experience of adult safeguarding and homelessness. In keeping with Making Safeguarding Personal, immediately following the introduction is the section on ‘Beyond listening to hearing and responding – learning from voices of lived experience.’ The key messages in this section come from reflective presentations given in a webinar, supplemented with personal testimonies that can be found in safeguarding adult reviews (SARs).

There is considerable synergy between what can learned from hearing from, and responding to people with lived experience and from the findings and recommendations from research and from SARs. An evidence-base exists for what good looks like across four domains of practice and management of practice. This evidence-base is then further developed in the ensuing four sections. The focus is on ‘further learning’, reinforcing and elaborating the core components of positive practice.

‘Further learning on direct work with Individuals’ renews the focus on person-centred practice. It questions particular narratives, especially about lifestyle choice and non-engagement, and emphasises the importance of a psychologically-informed approach and of professional curiosity. That curiosity refers both to the importance of seeking to understand the person’s journey into homelessness but also of reflectiveness about assumptions, pre-judgements and bias that may implicitly influence how we respond. The importance of thorough assessments of care and support needs, risk, mental capacity and mental health is also emphasised. The ‘Further learning for the team around the person’ section gives particular prominence to legal literacy and to safeguarding literacy, alongside the need for whole system partnership working and the use of different types of panels, strategy meetings and conferences.

The ‘Further learning for organisations supporting the team’ section considers how senior managers can best support and develop their staff, supervise decision-making and commission effective services. Particular emphasis is given to how organisations can enhance practitioner and manager legal literacy, and use the power commissioning to improve service provision. Finally, the section entitled ‘Governance’ explores how safeguarding adults boards (SABs) can demonstrate effective leadership in this field of practice through promoting a governance conversation about where strategic responsibility for homelessness should best reside. Guidance is also offered on how SABs can translate learning from SARs and from fatality reviews into initiatives designed to demonstrate outcomes across knowledge and skill acquisition, attitudinal change, policy and practice enhancement, and improvements in people’s wellbeing.

The eight webinars that informed the development of this briefing were held virtually as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. One of the webinars explicitly focused on responses during the pandemic to safeguarding people experiencing homelessness and all of the webinar presenters were conscious of the implications of this context. The available learning is pulled together in the section ‘Learning lessons from the response to the pandemic.’ Doubtless, more learning will emerge as research projects report and as personal testimonies emerge from people with lived experience and from practitioners working with them. The briefing ends with a conclusion that emphasises the importance of learning lessons from the pandemic, namely retaining what has worked effectively in safeguarding and promoting the wellbeing of people experiencing homelessness, rather than returning unreflectively to previous policies and practice. The final section, ‘Resources’ lists some useful references.

A key message from this second briefing remains that multiple exclusion homelessness refers to people with care and support needs, who may well also be experiencing abuse and neglect (including self-neglect). Adult safeguarding responsibilities are therefore also engaged. A key aspiration for this second briefing is that it will further assist SABs and other key decision-makers in deciding how to review and respond to the learning that emerges from cases involving multiple exclusion homelessness. The questions that follow here, which appeared originally in the first briefing, are designed to support your reflections and to promote action planning as you read through the briefing. Leadership is everyone’s responsibility and the questions are directed at those holding different roles in the partnership that underpins adult safeguarding and multiple exclusion homelessness.

Key questions for practitioners

- Where does your practice correspond with the components of effective practice for working with individuals?

- What supports you to practise in line with the evidence-base?

- What examples of positive outcomes from practice can you share?

- What gets in the way of practising in line with the evidence-base?

- How might you advocate for policy, organisational and system change to enable practice to mirror more closely “what good looks like?”

Key questions for operational managers

- How closely does practice correspond with the components of effective practice and management of practice described in this briefing?

- What supports practice in line with the evidence-base?

- What examples of positive practice can you share?

- What gets in the way of practising in line with the evidence-base?

- How can you promote and support effective practice when working with adults who experience multiple exclusion homelessness?

- How can you support reflective practice across teams?

Key questions for strategic managers

- How closely do single and multi-agency practices, policies and procedures correspond with the components of effective practice and management of practice described in this briefing?

- What supports whole system collaborative working in line with the evidence-base?

- What examples of positive practice can you share?

- What gets in the way of services aligning with the evidence-base?

- How can you promote and support culture change and service development for work with adults who experience multiple exclusion homelessness?

Key questions for SABs and elected members

- What level of reassurance do you have that services are aligned to deliver practice that corresponds with the evidence-base presented in this briefing?

- How are you holding agencies and the multi-agency partnership to account for policy and practice in the field of adult safeguarding and multiple exclusion homelessness?

- Are there gaps in policies, procedures and protocols that need to be filled?

- How have lessons from audits and SARs, completed locally or elsewhere, informed practice and service development?

- What examples of positive practice can you share?

Introduction

This briefing builds on an earlier publication that set out the evidence-base for positive adult safeguarding practice with people experiencing multiple exclusion homelessness. That earlier briefing summarised relevant law on adult safeguarding and homelessness and analysed the learning from safeguarding adult reviews (SARs). It then filtered effective practice through four domains – direct work with individuals, the team around the person, organisational support for the team, and governance. It concluded with a review of the impact of the legal, policy and financial context within which adult safeguarding and homelessness practice is located.

Funded by the Care and Health Improvement Programme (CHIP ) and supported by an Expert Reference Group, the original intention had been to promote that briefing through a series of regional workshops. Instead, as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, a sequence of eight virtual webinars, each with a thematic focus, was held between December 2020 and March 2021. Attendance at the webinars averaged 210 people, enabling a more extensive knowledge exchange than could have been achieved otherwise.

This briefing brings together the learning about practice, the management of practice, and the policy framework from those eight webinars. It also contains practice examples that those attending the webinars submitted afterwards. Once again, the learning is organised around the aforementioned four domains and the legal, policy and financial context that creates the overarching framework.

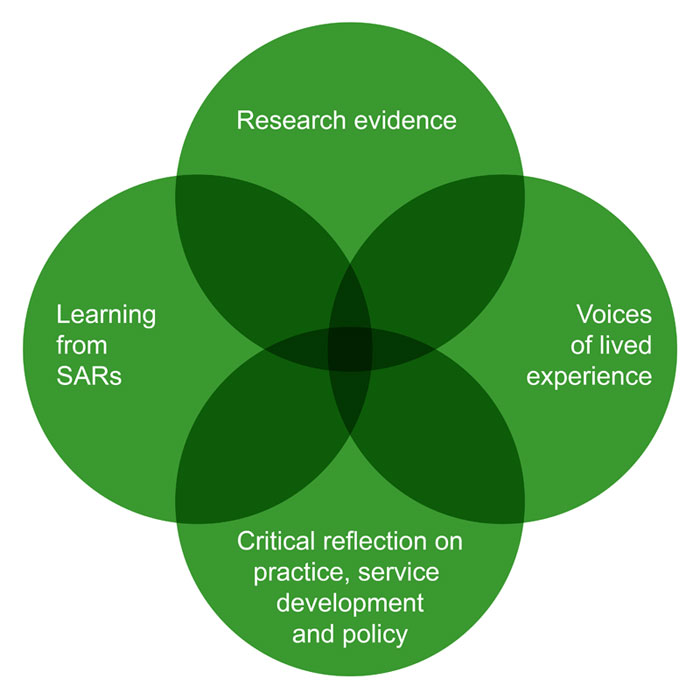

Knowledge is derived from many sources (SCIE Knowledge review 03: Types and quality of knowledge in social care) – research, policy development, practice, lived experience, inquiry and reflection. That diversity was reflected in the presentations given during the eight webinars and is reflected in this briefing, captured diagrammatically below.

The spirit of this briefing is one of appreciative enquiry, namely collating and disseminating examples of positive learning and practice from the different sectors involved, especially housing, health and social care, both statutory and third sector. The learning includes findings from the first national analysis of SARs and from recent thematic reviews of adult safeguarding and homelessness. The briefing captures what has already been learned and achieved by way of sector-led improvement and enhancement, and what priorities remain. It includes learning from experience of the COVID-19 pandemic. Most importantly, the briefing foregrounds learning from the voices of lived experience, in line with the commitment of making safeguarding personal.

The focus throughout this briefing is on learning. Firstly, in the section that follows immediately, the focus is on learning from the voices of lived experience. There then follow sections on learning in relation to direct work with people, the team around the person, organisational support for the team, and finally governance. These four sections build upon and further elaborate the evidence-base that was outlined in the first briefing (Adult safeguarding and homelessness: a briefing on positive practice). What has been learned from responses to the COVID-19 pandemic follows. This briefing finishes with a conclusion and list of further resources.

Learning from the voices of lived experience

[I want] people to listen to me and not make me feel like a bad person.”

When asked what he needed, Terence replied:

Some love, man. Family environment. Support.”

He wanted to be part of something real, part of real society and not just “the system.” (Thematic SAR on People who Sleep Rough)

I lost everything all at once: my job, my family, my hope…without [this help in Leeds], I’d already be dead. I’ve no doubts about that. If the elements hadn’t got me, I would have got me. Sometimes I have rolled up to this van in a real mess and they have offered help and support and got my head straight.”

(Understanding and Progressing the City’s Learning of the Experience of People Living a Street-Based Life in Leeds)

What hope do I have to ever recover or feel better when this keeps happening? I encourage anyone who truly cares to come and spend a day with me to see what it’s like to be helpless, when days feel like weeks, weeks feel like months.”

Ms I’s partner commented that at times “she could not help herself” because of the feelings that were resurfacing; access to non-judgemental services was vital and helpful, and that support is especially important when individuals are striving to be alcohol and drug free. It was during these times that stress, anxiety and painful feelings could “bubble up”, prompting a return to substance misuse to suppress what it was very hard to acknowledge and work through.”

These quotations are part of individual human stories. They remind us that there are multiple reasons why people become and remain homeless. They challenge us about the assumptions, unconscious bias and pre-judgements (prejudices) that we bring to the work. They remind us of the importance of relationships, of demonstrating emotional connection and of offering respectful and timely engagement that fits with the person’s own perception of their needs. They challenge us to be thoughtful not just about our responsibility but about our ethical duty of response-ability. They remind us of why making safeguarding personal is such an important practice principle.

There is no one typical person who is experiencing homelessness (A qualitative study of the experiences of people (with experience of rough sleeping/homelessness) who were temporarily accommodated in London hotels as part of the ‘Everyone In’ initiative). In any one location where there are people living street-based lives, there will be a range of ages, diverse languages and ethnic backgrounds, and different educational, employment and personal histories. There are multiple routes into living a street-based life, including debt, domestic abuse, loss of employment, substance misuse, mental ill-health, relationship breakdown and/or immigration status.

SARs sometimes comment on how little appears to have been known about the individuals with whom they work, their life experiences, the impact of significant episodes and their longer-lasting effects (National SAR Analysis April 2017 – March 2019). The omission of paying attention to an individual’s story results in tackling symptoms rather than addressing underlying causes. As one SAR pointed out (Thematic SAR on People who Sleep Rough), drawing on the observations of Ms I’s partner, attempting to change someone’s behaviour without understanding its survival function will prove unsuccessful. The problem is a way of coping, however dysfunctional it may appear, for example to numb the distress arising from adverse experiences. Put another way, individuals experiencing multiple exclusion homelessness are in a “life threatening double bind, driven addictively to avoid suffering through ways that only deepen their suffering.”

A poem captures vividly not just one individual’s voice but the depth of detail of their experience. Little of this appears to have been known to the practitioners and services that encountered him. He was described as reluctant to engage but it may rather have been that services did not find a way to respond to his “uniqueness” and to engage with him.

You found me and took me to places I had only dreamed

I found you in bottles, cans, and in pubs

Then later you showed me off- licenses, bars and clubs

For a while we just met on weekends with our friends

But over the years the drink changed with the trends

You started to change me and took over my life

You affected my work, my children and my wife

From a friend to an imposter, you started to be

I tried to ignore you and ask you to leave

You started to control me and take over my mind

The hope of you leaving was now left behind

I started to believe you wanted me dead

Still, I turn to you daily for relief from my head

I gave you my hand, which you took with a smile

You showed me dark places, we walked down the aisle

You left me to ponder the end of my life

I considered them all: pill, spirits and knife

How has this happened to the boy at the start

You lied to me, hurt me and have broken my heart

I thought I had beaten you time again

But you wanted to kill me, you are here till the end

I pleaded and begged, I got down on my knees

I didn’t understand that I had a disease

It would take more than my willpower to keep you at bay

I needed support to get through everyday

For now, you are dormant, but I know you will be back

Unless I do what is suggested and stay on the track

My family and support, they keep everything at ease

I am doing everything I can to arrest the disease

So, I am writing this poem to say my goodbyes

But when I read what you have done to me, I started to cry

Please if you read this and think alcohol may be your friend

Alcohol will kill you; it’s there till the end.

Presentations from experts by experience at the webinars, some of whom are now working as practitioners helping others to access the support that they themselves were able to respond to, contain crucial messages about, and provide further endorsement for components of positive practice across the different domains. These key messages are summarised below.

Direct work with individuals

- Engagement – recognise that people may be wary of professionals and services, possibly due to past experiences of institutions and the care system; appreciate that individuals may feel alone, fearful, helpless, confused, excluded, suicidal and depressed, unable to see a way out.

- Professional curiosity – “I was not asked ‘why?’” There is always more to know. Experiences (traumas) had a “lasting effect on me.” “Appreciate the beginning of the journey.”

- Partnership – “work with me, involve me, and support me.” “Keep in touch so that we know what is going on.” Help with form filling, bank accounts and other practicalities.

- Environment for engagement – what are we offering? A faceless centralised service in an office block that is hard to get to, with security cameras and guards, officers with lanyards, tickets, queues and screens? A telephone waiting system that even practitioners cannot bypass? Or a one-stop neighbourhood “hub” with allocated and contactable workers, no tickets and people who know you?

- Person-centred – see the person and, where necessary, adapt our approach; “people did not see beyond the sleeping bag”; challenge misconceptions of people who are homeless and any evidence of assumptions (unconscious bias) that someone may be undeserving; there are multiple reasons behind why a person may become homeless.

- Assessment – what does this individual need? Do not assume or stereotype. “I believe I found accessing services harder than my partner as I am black. I often felt stereotyped. I know my community finds it harder to take up help from the system.”

- Language – be careful and respectful about the language we use; words and phrases can betray assumptions. For example, who is not engaging? What does substance misuse imply?

Team around the person

- Collaboration – widen the multi-agency, partnership and colocation approach; a breadth of expertise is needed to respond to individuals’ complex needs involving physical and mental health, substance use and homelessness.

- Safeguarding – do not assume that people know what adult safeguarding actually is; for some it may be understood as the removal of children and as practitioners “working against, not with me.”

Organisations supporting the team

- Commissioning – focus on evidence-based practice and what works. Hostels and night shelters are not suitable for everyone and can be more frightening than the streets. Wrap-around support is often crucial – “I would not have coped otherwise.”

- Managerial oversight – understand the barriers to effective practice and learn from positive outcomes.

- Supervision and staff support – support a culture of reflective practice across teams to enhance practitioner wellbeing and resilience.

- Service development with commissioners and providers – use our expertise and experience to promote improvement and enhancement.

Governance

- Review – learn from failures.

- Training – education is essential so that practitioners and managers understand the multiple routes into homelessness and the pathways for prevention, intervention and recovery.

- Involvement – use our expertise.

- Audit – not just tick boxes but outcomes that matter to people.

National legal, policy and financial context

- Policy - reform should be guided by evidence.

- COVID-19 - learn from the “everybody in” initiative during the pandemic, which enabled people living street-based lives to settle in accommodation, with support to meet their health and social care needs.

Evaluations of Housing First and Community Outreach projects also sometimes contain testimonies from people with lived experience. They highlight and reinforce the importance of building trust, providing practical as well as emotional assistance, and advocacy alongside them with service providers. Several soundbites and themes stand out from these testimonies and from the presentations by those with lived experience of homelessness.

“Nothing changes if nothing changes” – a recognition that change has to come from within, but that practitioners and services have to adapt also. Lives will not be transformed from behind computers.

“Change will come” – a recognition that relationships can be transformative when they instil hope, demonstrate care and empathy, and offer practical and emotional support to achieve empowering change. Complex needs and multiple disadvantages can be overcome; there is a way back when individuals feel cared for and listened to. “We know the fundamentals – build on that.”

Further learning on direct work with individuals

The evidence-base for best practice when working with individuals who are homeless and at risk has been built from research and SAR findings. It comprises nine building blocks (Adult Safeguarding and Homelessness: A Briefing on Positive Practice).

- Person-centred approach, keeping in contact

- Concerned curiosity

- Exploring non-engagement and repeating patterns

- Understanding the person's history

- Exploring the impact of trauma and adverse experiences

- Thorough mental capacity and mental health assessments

- Thorough risk and care and support assessments

- Thinking family

- Seeing transitions as opportunities

A person-centred approach is embedded in the legal framework that accompanies the Care Act 2014. The Care and Support Statutory Guidance enshrines the principle of involvement , putting the person at the heart of the assessment process in order to understand their needs, desired outcomes and wellbeing, and to deliver better care and support. On the themes of involvement and thorough care and support assessments, the statutory guidance further advises that individuals should be provided with questions in advance, in an accessible format, to help them prepare. To promote engagement and involvement, consideration should be given to any preferences an individual may have regarding the location, timing and format of an assessment.

Learning from one community outreach project captures the essence of this approach. Its evaluation emphasised the importance of the individual retaining ownership of goals and the progress steps towards achieving them. It emphasised also the importance of a strengths-based approach and taking time to build rapport and trust. Finally, the approach had to be needs-led.

A consistent finding within SARs, however, is that individuals with complex needs are expected to keep appointments at designated times and specified locations, without apparent consideration of the practicality and feasibility of doing so, with cases then closed on grounds of non-engagement. Put another way, issues of social justice and oppression may make it more difficult for individuals experiencing homelessness to access support in relation to traumatic experiences; mental distress and substance use, the latter sometimes is a means of coping with painful and distressing experiences and makes it harder to access support (Trauma-informed and reflective practice in safeguarding people experiencing homelessness). Practitioners and services, therefore, must question the “did not engage” narrative by asking what they can do to facilitate engagement (Understanding care assessments and safeguarding planning for people experiencing homelessness).

It is important to remember that the threshold for care and support assessments is simply an appearance of need. Where an individual may have substantial difficulty in becoming and maintaining their involvement, an advocate must be appointed to provide representation and support during assessment, care planning and reviews. SARs have found that this entitlement to advocacy is sometimes overlooked (National SAR Analysis April 2017 – March 2019).

Care and support assessments must be balanced, considering all needs equally. Assessment should focus on understanding and defining an individual’s needs; it should not start from a position of what services are available and/or normally provided. With individuals experiencing homelessness, assessment and the provision of assistance must appreciate the inter-connectedness of accommodation and social care needs and outcomes. Accordingly for example, one single homeless pathway offers not just supported accommodation but a wide range of support and accommodation options, using a psychologically-informed approach and awareness of trauma.

Assessments should be characterised by professional curiosity rather than taking at face value and without exploration as to what an individual says. Thus, how do they come to be the person that you encounter now? A Care Assessment toolkit is available as guidance.

Professional curiosity about the “there and then” of people’s experiences, in order to understand them in them in the “here and now,” may identify the on-going impact of trauma and adverse experiences. It is not inevitable but trauma is both a likely precedent for, and outcome of homelessness. People who are homeless are highly likely to experience violence, abuse and anti-social behaviour. The term “multiple exclusion homelessness” recognises the importance of exploring and, where identified, addressing the impact of trauma. Multiple exclusion homelessness refers to extreme marginalisation that includes childhood trauma, physical and mental ill-health, substance misuse and experiences of institutional care. Adverse experiences in childhood can include abuse and neglect, domestic violence, poverty and parental mental illness or substance misuse. For many of those who live street-based lives, homelessness is a long-term experience and associated with tri-morbidity (impairments arising from a combination of mental ill-health, physical ill-health and drug and/or alcohol misuse) and premature mortality (Multiple exclusion homelessness and adult social care in England: exploring the challenges through a researcher-practitioner partnership).

SARs have been critical of interventions that address symptoms rather than causes of behaviour. For example, one SAR reported the observations of an individual’s partner: “At times she could not help herself because of the feelings that were resurfacing; access to non-judgemental services was vital and helpful, and that support is especially important when individuals are striving to be alcohol and drug free. It was during these times that stress, anxiety and painful feelings could “bubble up”, prompting a return to substance misuse to suppress what it was very hard to acknowledge and work through.” As the review further acknowledged, attempting to change someone’s behaviour without understanding its survival function will prove unsuccessful. The problem is a way of coping, however dysfunctional it may appear. Too often services respond to symptoms and not causes. Put another way, individuals experiencing multiple exclusion homelessness are in a “life threatening double bind, driven addictively to avoid suffering through ways that only deepen their suffering.” A psychologically-informed approach recognises the extent, impact and effect of trauma, and responds sensitively to it, through the medium of safe and respectful relationships, trust and transparency, careful use of language, compassion and empathy, a willingness to connect emotionally and a readiness to learn from those with lived experience (Trauma-informed and reflective practice in safeguarding people experiencing homelessness). It also means that the length of involvement must be determined on a case-by-case basis and not pre-ordained by organisational procedures. These are the same fundamentals as identified earlier by those with lived experience.

Effective safeguarding depends on robust risk assessment. Discrete tools are available (Protecting adults at risk: the London multi-agency policy and procedures to safeguard adults from abuse. Practice guidance: safeguarding adults risk assessment and risk rating tool), whilst some SABs have integrated risk assessment templates into procedures for different types of abuse and neglect (Norfolk SAB Self-Neglect Hoarding Strategy and Guidance Document). Risk assessment explores both the likelihood of different risks arising and their potential significance. One risk assessment tool that focuses on homelessness explicitly is built around three questions (Safeguarding toolkit): whether the individual has a safe place to stay where their basic needs can be met; whether they understand concerns about the level of risk to their wellbeing, and what help they need to protect themselves and how agencies should work together. There are four sections:

- The adult’s needs and the risks they face – focusing on care and support needs, physical and mental health needs, substance misuse, and also decisional and executive capacity and any evidence of coercive and controlling behaviour that may impact of decision-making.

- Chronology of events (short and long-term) – building up a picture of a person’s life journey and the impact of adverse experiences (loss and trauma) on daily living rather than just relying on how a person presents on the day of assessment.

- Immediate risk factors – immediate needs to prevent abuse or neglect, including self-neglect, and to protect the person from harm, using discretionary powers (Section 19, Care Act 2014).

- Protection planning – continually reappraising the effectiveness of risk mitigation plans to avoid normalisation of, or desensitisation from risk (Understanding care assessments and safeguarding planning for people experiencing homelessness).

Different narratives can obstruct risk assessment. One powerful narrative to guard against is the assumption of “lifestyle choice.” For example, with individuals who are alcohol-dependent, it is easy to view them as choosing their lifestyle but the reality will be more complex (Safeguarding Vulnerable Dependent Drinkers). Another is the assumption that an individual can protect themselves. These narratives can lead practitioners to under-estimate risk. Conversely, the protection imperative narrative can also obstruct risk assessment, the neglect of an individual’s strengths and resilience, which can lead to an over-estimation of risk. Particularly when there are repetitive patterns of need and risk, the aim is to build a relationship that can support respectful challenge and dialogue about how to mitigate (rather than necessarily remove all) risk and promote agreed objectives relating to wellbeing and autonomy. The medium for change is a relationship, which expresses concerned curiosity about an individual’s experiences and what has led them to where they are now, and which seeks to identify and build on their strengths, goals and aspirations in order to keep themselves safe and promote their choices (Trauma-informed and reflective practice in safeguarding people experiencing homelessness). This is a person-centred, psychologically-informed environment.

People experiencing homelessness often present with mental health concerns. The National SAR Analysis highlighted both good practice and shortfalls regarding mental health assessments and interventions for people with significant mental distress but not in acute crisis, as the graphic below summarises. Guidance (Pathway with Lambeth Council) is available on the use of mental health and mental capacity legislation (Safeguarding Vulnerable Dependent Drinkers).

Assertive outreach is effective but building engagement takes time and persistence

Good practice

- Timely and thorough assessments

- Understanding and use of law

- Referral practice

- Effective collaboration and communication

- Use of adult safeguarding

- Assertive outreach and follow-up

Practice shortfalls

- Failure to differentiate between mental wellbeing and MHA 1983 assessments

- Poor (risk) assessments and reviews

- Failure to think family and assess dynamics

- Lack of outreach

- Case bouncing/revolving door

- Referral pathways into mental health – who can refer?

- Lack of secondary mental health services for people not in immediate crisis

- Lack of understanding of MHA 1983

- Failure to use safeguarding procedures

- CPA guidance not followed

- Parity of esteem, for example mental health overshadowing physical health concerns

A similar picture emerges from the national SAR analysis on mental capacity assessment

Good practice

- Robust capacity assessments and best interest decisions

- Outcomes clearly recorded

- Assessment clearly mapped against MCA requirements

Practice shortfalls

- Failure to assess or review

- Poor assessments

- Misunderstanding of MCA principles

- Misunderstanding of diagnostic test

- Neglect of executive capacity

- Neglect of advocacy

- Assumptions about lifestyle choice

- Poor recording

- Lack of confidence

When working with people experiencing homelessness, some of whom will be using alcohol or other drugs, an accurate interpretation of Mental Capacity Act 2005 principles is essential. The presumption of capacity should not be read as meaning that there is no need to investigate capacity. An apparently unwise decision may be reason to doubt capacity and to complete an assessment (Legal Literacy: Navigating the Complexities (and Misconceptions) in the Legislation).

Reliance must not be placed solely on what a person says. Adverse experiences, trauma and prolonged substance abuse can result in frontal lobe brain damage, which will affect an individual’s behaviour. Assessing executive functioning is therefore essential. NICE (Decision-Making and Mental Capacity) has advised that “practitioners should be aware that it may be more difficult to assess capacity in people with executive dysfunction – for example people with traumatic brain injury. Structured assessments of capacity for individuals in this group (for example, by way of interview) may therefore need to be supplemented by real world observation of the person's functioning and decision-making ability in order to provide the assessor with a complete picture of an individual's decision-making ability.”

SARs have also highlighted the importance of assessing executive functioning. Thus: “the concept of “executive capacity” is relevant where the individual has addictive or compulsive behaviours. This highlights the importance of considering the individual’s ability to put a decision into effect (executive capacity) in addition to their ability to make a decision (decisional capacity). ” Again: “To assess Ruth as having the mental capacity to make specific decisions on the basis of what she said only, could produce a false picture of her actual capacity. She needed an assessment based both on her verbal explanations and on observation of her capabilities, ie “show me, as well as tell me”. An assessment of Ruth’s mental capacity would need to consider her ability to implement and manage the consequences of her specific decisions, as well as her ability to weigh up information and communicate decisions. ” Other SARs have highlighted that individuals may be driven by compulsions that are too strong for them to ignore. Their actions often contradict their stated intention, for example to control their alcohol use. In other words, they were unable to execute decisions that they had taken. The compulsion associated with an addictive behaviour can be argued to override someone’s understanding of information about the impact of, for example, their drinking, calling into question a lack of capacity (Safeguarding Vulnerable Dependent Drinkers).

The initial focus for the assessment should be on whether an individual can understand, retain and use or weigh information in order to reach a decision. Thus, is the individual able to engage with feedback that is shared when their behaviour has been observed? If not, is that because of an impairment or disturbance in the functioning of the mind or brain? (Legal Literacy: Navigating the Complexities (and Misconceptions) in the Legislation). Resources (including templates, Pathway with Lambeth Council) are available to assist with the completion of mental capacity assessments.

In summary, direct work with individuals can result in improved emotional and physical wellbeing, reduced psychological distress, and greater financial and housing security. This will often depend, however, on the persistence that practitioners demonstrate and their ability to offer supportive, trauma-aware, intensive and flexible relationship-based support and assistance. It will also depend on organisational endorsement for this approach and how well the team around each individual comes together. It is to these two domains of practice that this briefing now turns.

Further learning for the team around the person

The evidence-base for best practice within the team around the person comprises eight building blocks (Adult Safeguarding and Homelessness: A Briefing on Positive Practice).

- Services work together to provide integrated care and support (collaboration)

- Information and assessments are shared

- Referrals that clearly state what is being requested

- Multi-agency risk management meetings to plan and review

- Exploration of all available legal options (legal literacy)

- Using adult safeguarding enquiries to coordinate case management (safeguarding literacy)

- Using pathways within policies to address people's needs

- Comprehensive recording of practice and decision-making

Collaboration between practitioners and their services is essential to ensure the timely provision of care and support (Care and Support Statutory Guidance). Most individuals who live street-based lives will present with a combination of housing needs, physical health and mental health concerns, substance misuse and/or psycho-social factors. This highlights the importance of convening a bespoke team around the person, combining a range of expertise to ensure wrap-around assessment and support (Care and Support Statutory Guidance). Assertive outreach is most effective when guided and support by collaboration between agencies. When several services are involved, it is helpful to clarify which practitioner will undertake a mental capacity assessment.

Evaluations of initiatives involving people experiencing homelessness consistently recognise the necessity of a collective effort to address systemic issues – it is “everybody’s business.” To improve people’s mental and physical wellbeing, to enable individuals to access and to sustain tenancies, and to achieve reductions in substance misuse and anti-social behaviour/offending, requires whole system partnership working across mental health and substance misuse providers, outreach homelessness teams, councils, adult social care, police, homeless support workers, primary care and secondary health care. In this context, it is important to remember the duty to cooperate enshrined in the Care Act 2014 and, especially, collaboration between adult social care and housing. Evidence from project evaluation and SARs (National SAR Analysis) continues to stress also the value of appointing a keyworker, both to support individuals living street-based lives to access and engage with services, but also to coordinate provision of support and assistance.

SARs frequently criticise the lack of safeguarding literacy (National SAR Analysis), namely missed opportunities to refer safeguarding concerns, implicit hierarchies of expertise that lead to concerns (for example from third sector practitioners being side lined), or failure to conduct enquiries where the three criteria are clearly met, namely for an adult in a council’s area, the individual has care and support needs, is experiencing or at risk of abuse and/or neglect (including self-neglect), and is unable to protect themselves as a result of their care and support needs (Section 42 (1), Care Act 2014). Pathways should be clearly identified through which referrers can challenge and/or escalate concerns about decision-making in response to referred adult safeguarding concerns. Narratives of lifestyle choice and mental capacity sometimes derail responses to referred adult safeguarding concerns. There is no reference to mental capacity or consent in the criteria in section 42 (1) (Legal Literacy: Navigating the Complexities (and Misconceptions) in the Legislation). Even where the duty to enquire is not met, the council must still consider and record how any identified risk will be mitigated, for example by referral to another agency and/or convening a multi-agency risk management meeting to agree a forward plan.

Where referrals are sent, they should clearly present relevant information and highlight what is being requested (National SAR Analysis April 2017 – March 2019). Multi-agency risk management meetings are useful for reviewing how practitioners and services are working together, for highlighting and addressing patterns for both the individual and how agencies are responding, and for setting SMART actions that are then monitored and reviewed (Understanding care assessments and safeguarding planning for people experiencing homelessness).

There will be occasions when multi-agency risk management meetings prove unable to mitigate risks and significant concerns remain. A creative solutions board, or similar arrangement, may prove helpful at this point (Creative Safeguarding for People with Multiple Disadvantage). Board meetings discuss individuals at risk of abuse or neglect where previous responses have not worked. The meeting seeks to plan creatively, with the individual at the centre of reaching for a different solution. It is recognised that the whole system may need to change and flex to deliver a better outcome. This requires a commitment to collaboration, with agency representatives having the authority to commit resource and change the offer from their service. People with lived experience are members of the board. This demonstration of the team around the person becomes “my team around me.”

Safeguarding literacy requires legal literacy. Indeed, safeguarding adults in the form of the section 42 duty to enquire, and safeguarding adults in the form of preventing (further) risks from homelessness, entail navigating legal complexity – balancing different legal rules and competing human rights, and considering all legal options (including referral to the Court of Protection) when what may be in a person’s best interests is uncertain (Legal Literacy: Navigating the Complexities (and Misconceptions) in the Legislation).

Legally literate practitioners and managers (Legal Literacy: What it is and why it matters):

- Have sound knowledge of legal rules and standards in administrative law

- Can apply legal rules to real world scenarios

- Abide by professional codes of ethics, which include acting lawfully

- Ensure that human rights are observed

- Are confident in identifying options, weighing their respective merits, and justifying the choices made

There are five essential components to legal literacy, to constructing and, if necessary, defending a decision.

The first is giving due consideration to the potential contribution of diverse legal rules in primary legislation, the detail for which was given in the earlier briefing (Adult Safeguarding and Homelessness: A Briefing on Positive Practice).

Mental Health Act 1983

Housing Act 1996

Human Rights Act 1998

Mental Capacity Act 2005

Equality Act 2010

Care Act 2014

Homelessness Reduction Act 2017

The second is being able to demonstrate how practice has promoted a person’s wellbeing, namely:

- personal dignity

- physical and mental health, and emotional wellbeing

- protection from abuse and neglect

- control over day-to-day life

- participation in activities

- social and economic wellbeing

- domestic, family and personal wellbeing

- suitability of living accommodation

- contribution to society

- involvement in decision-making.

The third component is being able to demonstrate that explicit consideration has been given to human rights, as codified in the Human Rights Act 1998 and in United Nations Conventions.

The fourth is being able to show how decision-making has upheld standards for the exercise of authority, which feature in administrative law.

Public authorities must act lawfully:

- not exceed their powers

- respect human rights

- promote equalities.

They must observe standards in the use of statutory authority

- make timely decisions

- take account of all relevant considerations

- avoid bias

- share information and consult

- provide a rationale for the exercise of discretion.

Finally, due regard must be paid to case law. Examples include reminders about the right to advocacy , the consequences of acting unlawfully and violating a person’s human rights , and what might constitute relevant information when undertaking capacity assessments.

The earlier briefing (Adult Safeguarding and Homelessness: A Briefing on Positive Practice) provided detailed guidance about the legal mandate, the powers and duties, for safeguarding adults experiencing homelessness, including those with no recourse to public funds. Without repeating that detailed guidance, it is worth emphasising again, key powers and duties to reinforce the importance of legal literacy (Legal Literacy: Navigating the Complexities (and Misconceptions) in the Legislation):

- Councils have a duty to meet a person’s care and support needs that arise from or are related to physical or mental impairment or illness.

- The duty to assess arises when a person appears to have a need for care and support (section 9, Care Act 2014).

- Assessment should continue despite a person’s refusal to engage, where the individual lacks capacity and it is in their best interests, or where the individual is experiencing or at risk of abuse and/or neglect, including self-neglect (section 11, Care Act 2014).

- The council must meet eligible needs (section 18, Care Act 2014).

- Councils have a power to meet needs that do not meet the eligibility criteria (section 19(1), Care Act 2014), so the reasons for exercising, or not, this discretion must be clearly recorded.

- There is a power to meet needs and provide emergency accommodation pending an assessment (section 19(3), Care Act 2014).

- Throughout involvement with a person, the council must aim to promote their wellbeing (section 1, Care Act 2014) and to enhance their human rights, most especially the right to life, the right to live free of inhuman and degrading treatment, and the right to private and family life (Human Rights Act 1998).

- The duties and powers arise when a person is ordinarily resident in the council’s area or is present and with no settled place of residence.

- Care and support needs can be met through the provision of any type of accommodation (section 8(1), Care Act 2014) but there is no duty to meet needs that arise solely from destitution (section 21, Care Act 2014).

For those with no recourse to public funds, alongside the powers and duties outlined above, the focus must also be on providing practical assistance to help them secure changes to their immigration status.

Further learning for organisations supporting the team

This part of the evidence-base comprises six elements (Adult Safeguarding and Homelessness: A Briefing on Positive Practice):

- Supervision to promote reflection and analysis of case management

- Supporting staff

- Management oversight of decision-making

- Access to specialist legal, safeguarding, mental capacity and mental health advice

- Providing workforce development and ensuring that workplace culture and policies enable effective practice

- Developing commissioning to respond to the needs of people experiencing multiple exclusion homelessness

Supervision , support and management oversight have been consistently highlighted by SARs (National SAR Analysis) as essential components of achieving best practice, particularly with complex and challenging situations. Working in a psychologically-informed environment, providing trauma-informed care and support, maintaining relationship-based practice, and navigating ethical dilemmas about whether, when and how to intervene – all will depend for their effectiveness on organisational recognition of the psychological needs of staff (Trauma-informed and reflective practice in safeguarding people experiencing homelessness). There are several elements within this recognition, namely access to specialist psychological advice, training, and provision of physical and social spaces in which practitioners, managers, and service users (What works and what doesn’t for homelessness? A perspective informed by lived experience) feel safe-enough to reflectively explore how to move forward. One example is an organisational safeguarding group where practitioners can bring situations about which they are concerned and seek advice and support from colleagues with specialist expertise, for example in mental health and substance misuse. Reflective supervision explores the emotional impact of the work and tries to make sense of uncertainty about how to move forward. It is developmental, appreciative, and supportive, collaborative but constructively challenging. There is a focus on analysis, planning and review. In essence, it is the provision of a secure base.

Staff support, management oversight, alongside workforce development and access to specialist advice, are also essential components for ensuring legally literate decision-making (Legal Literacy: What it is and why it matters). This comprises:

- access to legal advice

- training on legal literacy

- briefings to update knowledge

- decision-making

- reflective spaces to consider options

- time to compile a legally literate assessment

- law talk informs practice

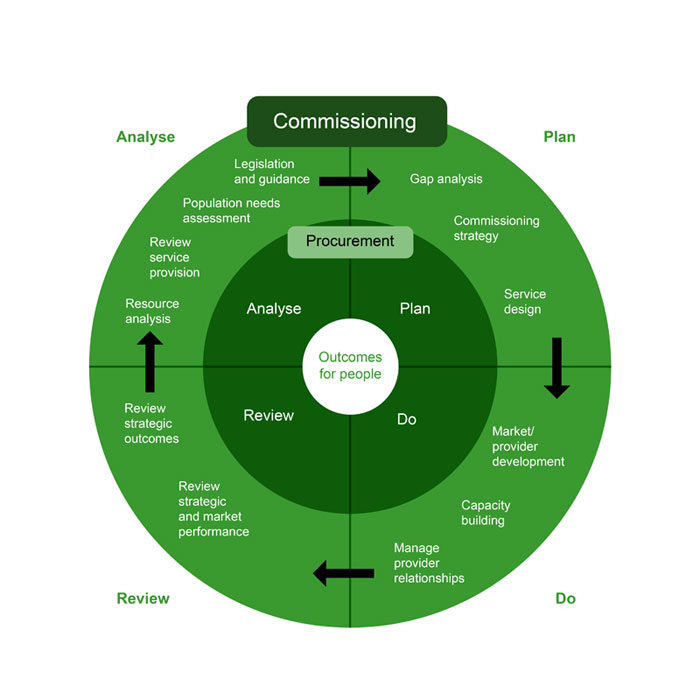

Commissioning is also an essential component for achieving best practice in responding to the accommodation, health and social care needs of people experiencing homelessness. Thematic reviews involving homelessness (Thematic Safeguarding Adults Review regarding People who Sleep Rough) have noted the complexity of funding and commissioning arrangements, the importance of positive collaboration between commissioners and with providers, and the obstacles created by the way in which provider contracts are configured and renewed, which create considerable risk in the system. One SAR (Understanding and Progressing the City’s Learning of the Experience of People Living a Street-Based Life in Leeds) highlights the benefits of joint commissioning to develop pathways to recovery and sustained community living for those who have led street-based lives.

Commissioning involves analysis, planning, securing/purchasing and reviewing services. Providers echo the concerns reported by SARs, noting particularly the impact of more than a decade of financial austerity, a lack of reciprocity and collaboration, with providers not being seen as equal partners, incomplete data because of the invisibility of some forms of homelessness, unhelpful performance indicators and the absence of integrated approaches (“Commissioning to safeguard people who are homeless: a provider’s perspective).

There is, however, an evidence-base for best commissioning practice that incorporates known enablers. These include respect and reciprocity, seeing providers as equal partners, contracts that support investment in skill development to enhance quality, the involvement of people with lived experience in service design and delivery, and performance indicators that are outcome focused. One framework for conceptualising and enhancing the power of commissioning comprises five elements, namely that the process should be:

- person-centred and outcomes focused

- inclusive and co-produced with people with lived experience and with providers

- well-led, drawing on evidence about what works

- integrated, a whole system approach

- aimed at promoting a sustainable and diverse market-place (Commissioning to safeguard people who are homeless: a provider’s perspective).

Another framework takes the cycle of commissioning and explores the components within each quadrant (Homelessness and adult safeguarding: best practice in commissioning). Once again, coproduction and integration are recurrent themes, alongside market analysis and development, a person-centred approach that understands what people want and need, and capacity building that draws on evidence of “what works.”

Evaluations of projects also highlight the importance of commissioning. This involves thinking through, including with people with lived experience, the design and delivery of drug and alcohol services, mental health assessment and support, and access to adult social care, so that pathways for access are clear and arrangements sufficiently flexible to enable successful outreach to individuals.

Further learning on governance

This component of the evidence-base has five elements (Adult Safeguarding and Homelessness: A Briefing on Positive Practice):

- SAB promotes procedures for working with self-neglect and multiple exclusion homelessness

- SAB coordinates governance with Community Safety Partnership and Health and Wellbeing Board

- SAB uses SARs for learning and service development

- SAB audits cases involving self-neglect and multiple exclusion homelessness

- SAB uses the evidence-base to hold partners accountable for practice standards

Governance focuses on how organisations direct and control what they do, and specifically on the structures and processes that are designed to ensure accountability and transparency, equality and inclusiveness, lawful decision-making, responsiveness, and empowerment through participation (Safeguarding Adults Boards and multiple exclusion homelessness: the challenges of leadership and governance). SABs have specific governance responsibilities with respect to adult safeguarding. These are: to hold organisations to account, to provide oversight on the delivery and impact of strategic priorities for improvement and learning, and to seek assurance regarding the effectiveness of how services work together to prevent and protect adults from abuse and neglect. Mechanisms to implement these responsibilities include setting standards and issuing guidance, completing audits and SARs, provision of multi-agency training and operating quality assurance systems (“Safeguarding Adults Boards and multiple exclusion homelessness: the challenges of leadership and governance” and “Governance of adult safeguarding and homelessness: learning from safeguarding adult reviews, research and practice.)

If the governance of adult safeguarding is unequivocally the responsibility of SABs, strategic responsibility for homelessness is less clear. It may fall, variously, to the Health and Wellbeing Board, the SAB, the Community Safety Partnership, or a Homelessness Reduction Board. Accordingly, several thematic reviews have recommended that SABs should take the lead in convening a summit, a whole-system governance conversation, with a view to determining where strategic oversight will sit. There is no one model for where governance of multiple exclusion homelessness might reside; what works will vary, depending on local government and local governance structures. If the SAB does not take the strategic lead for multiple exclusion homelessness, its leadership contribution will be important in ensuring that adult safeguarding is not overlooked as strategic plans are being developed, implemented and reviewed.

SARs have also offered recommendations relating to governance of adult safeguarding in general and multiple exclusion homelessness in particular (National SAR Analysis April 2017). These recommendations echo themes that have appeared throughout this briefing, including coproduction, legal literacy, commissioning for quality, and relationship-based, trauma-informed practice.

Recommendations from SARs on governance

- Involve people with lived experience in the development of policies, procedures and protocols.

- Agree the main location for strategic leadership and oversight (two tier councils).

- Ensure strategies on homelessness contain overt references to (pathways into) adult safeguarding.

- Review procedures concerning people living street-based lives; high risk cases where individuals have capacity; risk assessment; frequent flyers; self-discharge.

- Reach out to national provider services (Royal Mail, utility companies, DWP).

- Clarify pathways for case reviews.

- Review impact of previous SARs.

Recommendations from SARs on enhancement of practice and the management of practice

- Ensure guidance is embedded in practice (training, case and supervision audits).

- Promote recognition of interface between homelessness and self-neglect.

- Audit adult safeguarding decision-making (section 42(1) and 42(2)) (legal literacy).

- Review pathways (into mental health; services for women).

- Review commissioner-provider relationships, including gaps in provision.

- Promote trauma-informed practice.

- Promote shared databases to build a shared case narrative.

Whatever governance arrangements are agreed locally, SABs will be “process catalysts” or a “guiding presence” to ensure that change happens. That involves a whole-system conversation about change, beginning with clarity about aims and objectives, informed by the evidence-base of what good looks like, and moving through an appraisal of the present state and what actions are necessary, by whom, to achieve and sustain desired change. It will be helpful to articulate where outcomes are expected, namely (Making any difference? Conceptualising the impact of safeguarding adults boards):

- Partner reactions: views of their experience of working with the SAB and in adult safeguarding

- Changing attitudes: perceptions of partnerships in adult safeguarding are modified

- Knowledge and skill acquisition: developing understanding and application in practice of procedures regarding assessment, intervention, purchaser/provider roles in adult safeguarding

- Changes in practice: implementing new learning about adult safeguarding by the workforce

- Changes in organisational behaviour:iImplementing new learning in organisational culture and procedures

- Benefit to service users and carers: improvements in wellbeing.

The description of desired outcomes should be informed by what SABs have found during audits, multi-agency training and, especially, SARs and fatality reviews. Originally developed by the London Borough of Haringey , other areas have adopted the practice of fatality reviews, with findings and recommendations feeding into the work of Health and Wellbeing Boards, informing commissioning decisions (Learning from deaths and solution focused responses to complex needs). SABs are increasingly commissioning SARs that involve homelessness. The national analysis contained 25 such reviews, representing 11 per cent of the sample (National SAR Analysis April 2017). In summary, there were 14 references to good practice, namely: rapport building, expression of humanity, provision of care and support and emergency accommodation, health services outreach, colocation of practitioners, and clear referrals. There were 42 references to practice shortfalls, as follows: delayed or missing risk, mental health and mental capacity assessments, unclear referral pathways, discharges to no fixed abode, lack of use of available legal rules, and absence of consideration of vulnerability. There were 18 recommendations, focusing on wrap-around support (health and care and support as well as housing), coordination of response, legal literacy, commissioning for health and social care as well as housing, and governance oversight.

SARs and fatality reviews continue to highlight the need for change across direct work with individuals, the team around the person, and organisational support for the team (Learning from deaths and solution focused responses to complex needs and Governance of adult safeguarding and homelessness: learning from safeguarding adult reviews, research and practice).

Reinforcing learning about direct work with individuals

- Engage with people about their experiences, taking time to develop a relationship of trust.

- Responding in a coordinated way to multiple accommodation, physical health, mental health, and care and support needs.

- Responding to substance misuse issues.

- Demonstrating professional curiosity.

- Being careful about the language used.

- Scrutinising the stories we tell ourselves and others about people who are experiencing homelessness.

- Recognising the diversity of people experiencing homelessness.

- Outreach and in-reach to improve access to services.

- Appreciate people’s resilience and strengths but also recognise fragility.

- Thorough assessments of mental capacity, mental health and care and support needs where individuals are rather than where we might expect to interview them.

Reinforcing learning about the team around the person

- The importance of flexibility of thresholds and eligibility criteria so that people’s needs are met and safeguarding is everyone’s responsibility.

- Understanding the risks associated with homelessness.

- Using enquiries to respond to adult safeguarding concerns were individuals have care and support needs and are experiencing abuse and/or neglect, including self-neglect.

- The importance of agencies working together, for instance when individuals present with mental health and substance misuse issues.

- Sharing information when people move out of area.

- Co-location.

Reinforcing learning about organisational support for team members

- Training to enhance recognition, understanding and responses to multiple exclusion homelessness.

- Co-design services with people with lived experience.

- Ensure support for staff working with complex situations.

- Joint commissioning.

Both SARs and fatality reviews, alongside safeguarding adult enquiries, can make significant contributions to improving practice and service enhancement. The important focus is on learning and it is timely to recall the duty to cooperate enshrined in the Care Act 2014. All SAB partners must cooperate to identify lessons to be learned from cases where adults with care and support needs have experienced serious abuse and/or neglect, and apply lessons learned to future cases.

Learning lessons from the response to the pandemic

The webinars from which much of the material for this briefing has been taken were virtual, owing to the COVID-19 pandemic. One webinar was specifically devoted to highlighting lessons learned with respect to safeguarding people experiencing homelessness from the beginning of the pandemic. Presentations in other webinars also made reference to the pandemic and its impact on homelessness.

On the one hand the pandemic has revealed social injustice and inequalities (Social injustice kills on a grand scale – health, homelessness and housing supply); on the other hand, it has demonstrated that national social policies, accompanied by central government investment, can be the difference that makes a significant impact. As thematic SARs have observed , social policies on social housing, including supported accommodation, and on welfare benefits, have made it increasingly difficult to provide safe and secure accommodation for people experiencing homelessness and to reduce the number of people living street-based lives. Structural issues, legal rules and social policies, such as poverty and immigration law, have been significant contributors to inequality, social exclusion and homelessness. A trauma-informed approach must, therefore, embrace social factors alongside individual personal adverse experiences (Adverse Childhood Experiences: What We Know, What We Don’t Know, and What Should Happen Next).

However, the “everybody in” initiative has proved successful in providing not just safe and secure accommodation for people living street-based lives but also wrap-around physical and mental health care, and care and support. One approach to best practice is a multi-agency effort coordinated through a Homelessness Forum that pulls together the work of statutory and third sector organisations to find solutions for people who have been living street-based lives, including those with no recourse to public funds. Recognising the multiple needs with which people experiencing homelessness present, a multi-disciplinary collaborative response is required that involves social care, substance misuse practitioners, mental health services, primary care and housing staff (Homelessness response to COVID-19). For individuals with no recourse to public funds, support through the “everybody in” initiative has included assistance to enable claims for settled status or leave to remain (Homelessness response to COVID-19).

The focus is then on identifying the level of support that a person will need to move into and sustain secure accommodation. Lower levels of required support will mean utilisation of the private rented sector, with floating support; higher levels of need will connect individuals with supported housing and Housing First. New grant funding streams have been used to increase the number of accommodation units. Once provided with accommodation, continued support is offered to promote testing and vaccination, prevent evictions and address health and social care needs.

Personal testimonies from people with lived experience have commented positively on the standard of accommodation offered, the approachability of staff and the opportunities for personal development. Research (A qualitative study of the experiences of people (with experience of rough sleeping/homelessness) who were temporarily accommodated in London hotels as part of the ‘Everyone In’ initiative) has also found that people who were accommodated as a result of the pandemic valued the kindness of staff, the room facilities and the warmth, safety and privacy afforded by having their own space. The practical support provided was also appreciated although some needs relating to health and medicine were not met.

The initiative appeared successful in preventing and protecting people from exposure to COVID-19. However, reinforcing the need for wrap-around support, not everyone with mental health problems had been well-connected into mental health services before being accommodated and some physical and mental health problems remained untreated. The more information that was provided about arrangements for moving on, the less stress and anxiety was experienced about next steps. Also reinforcing the need for wrap-around support, access to formal and informal social, financial and emotional support systems had been limited when people were living street-based lives, and outreach, or more assertive forms of assistance seemed helpful in breaking down barriers to seeking out support. Moreover, move-on accommodation must be of a reasonable standard and the wrap-around support that characterised the “everybody in” initiative must not be allowed to unravel once a person has moved on.

Further research data, personal testimonies and practitioner accounts will emerge in time about the on-going impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on people experiencing homelessness and about the effectiveness of local and national initiatives in response. A whole system conversation will be important to capture this learning and to embed it into future work with, and provision for people experiencing homelessness.

Conclusion

Care and Support Statutory Guidance requires that adult safeguarding is characterised by six principles. These principles apply, as this briefing has demonstrated, to working with people experiencing homelessness, whether that is Adult Safeguarding, using referral of concerns and the duty to enquire (section 42, Care Act 2014), or whether it is adult safeguarding in the broader sense, seeking to prevent abuse and/or neglect, and to meet an individual’s accommodation, health, and care and support needs. Elaborating the six principles provides a standard against which policy and practice locally can be evaluated.

- Empowerment – look beyond the presenting problem to the backstory; make every adult matter; listen, hear and acknowledge, see and build on the person’s strengths.

- Prevention – commissioning to avoid revolving doors and to provide integrated wrap-around support; transitions out of prison or hospital as opportunities to plan for meeting needs.

- Protection – address risks of abuse and neglect, and of premature mortality; in-reach and outreach to build up and sustain a relationship through which to provide practical assistance and emotional support.

- Partnership – no wrong door; make every contact count; be flexible about how to engage; build a team around the person.

- Proportionality – minimise risk; judge the level of intervention required.

- Accountability – get the governance right; system-wide leadership.

Populating the six principles draws on the evidence-base that is drawn from testimonies from people with lived experience alongside SAR and research findings. The realisation that there is an evidence-base for effective safeguarding with people experiencing multiple exclusion homelessness means that, as the United Kingdom emerges from the worst of the COVID-19 pandemic, services must not slip back to fragmented territoriality.

When central government updates its strategy for rough sleeping, it must draw on this evidence base. Otherwise, people who experience homelessness in the future may well be let down by the system again if learning from recent events is to inform support for people who experience homelessness.

Action planning - what needs to happen now?

Having read this briefing:

- What will you do next and why?

- What might the challenges be as you take these next steps?

- How could SAB partners, elected members, senior managers, operational managers and practitioners help?

- What examples of positive practice can you share?

Resources

Relationship between Housing and adult social care

Blood, I. (2019) Successful Relationships – Working Together across Housing and Social Care. Dartington: Research in Practice for Adults.

User experience

User experience briefings about being homeless during the pandemic.

Established and run by people with direct experience of homelessness, the Museum of homelessness records deaths of people living street-based lives and has a collection and archive of materials.

Learning from SARs

Since January 2020 SABs have published a number of SARs that reinforce the messages about best practice in this briefing.

- Thematic review – Manchester SAB (2020)

- Thematic review – Oldham SAB (2020)

- Bexley SAB – N (2020)

- Cornwall and Isles of Scilly SAB – Jack (2020)

- Herefordshire SAB – Samuel (2020)

- North Yorkshire SAB – Ian (2020)

- Northamptonshire SAB – Jonathan (2020)

- Bexley SAB – Paul (2020)

- Cambridgeshire and Peterborough SAB – Peter (2020)

- Solihull SAB – Paul (2020)

- Warwickshire SAB – Peter (2020)

- Teeswide SAB – Adult D (2021)

- Newham SAB – Peggy (2021)

Data

Comprehensive picture of homelessness is updated annually.

Learning from COVID-19

Lewer, D., Braithwaite, I., Bullock, M., Eyre, M., White, P., Aldridge, R., Story, A. and Hayward, C. (2020) ‘COVID-19 among people experiencing homelessness in England: a modelling study.’ Lancet Respiratory Medicine, 8, 1181-1191.

Neale, J. (2020) Experiences of Being Housed in a London Hotel as part of the ‘Everyone In’ Initiative. Part 1 – Life in the Hotel. London: Kings College London.

Neale, J. (2021) Experiences of Being Housed in a London Hotel as part of the ‘Everyone In’ Initiative. Part 2 – Life in the Month after Leaving the Hotel. London: Kings College London.

See also briefings produced by Homeless Link

Legal Literacy

Research in Practice has completed a change project on legal literacy that includes tools to support supervision and staff development, and to enhance organisational legal literacy.

Organisational resilience

Research in Practice has developed a resource to enhance organisational resilience.

Professional curiosity

Thacker, H., Anka, A. and Penhale, B. (2020) Professional Curiosity in Safeguarding Adults. Dartington: Research in Practice.

Webinars

All eight webinars were recorded and can be accessed on the Local Government Association (LGA) web pages. The slides used by the presenters have also been published on the same web pages, the links for which are given below. Each of the eight webinars was organised around a particular theme:

Foundations for positive practice in safeguarding people who are homeless

Presenters: Professor Michael Preston-Shoot and Bruno Ornelas

17 December 2020

Commissioning and provider services: safeguarding people experiencing homelessness

Presenters: Gill Taylor and Rebecca Pritchard

13 January 2021

Psychologically-informed and reflective practice in safeguarding people experiencing homelessness

Presenters: Katy Shorten and Lydia Guthrie

18 January 2021

Learning lessons from the response to Covid-19 regarding safeguarding people experiencing homelessness

Presenters: Susan Harrison, Atara Fridler, Laurence Coaker and Stephen Parkin

25 January 2021

Legal literacy in safeguarding people experiencing homelessness

Presenters: Professor Michael Preston-Shoot, Laura Pritchard-Jones and Henry St Clair Miller

15 February 2021

Governance of adult safeguarding and homelessness

Presenters: Jane Cook, Professor Adi Cooper and Professor Michael Preston-Shoot

23 February 2021

Tackling specific issues: safeguarding people experiencing homelessness

Presenters: Mike Ward, Barney Wells and Aileen Edwards and Alison Comley (Golden Key)

1 March 2021

Making every adult matter and every contact count – reviewing learning about positive practice in safeguarding people experiencing homelessness.

Presenters: Carl Price, Jason, John, Kinga and Tom (Independent Futures) and Claire Barcham

8 March 2021

Footnotes

Preston-Shoot, M. (2020) Adult Safeguarding and Homelessness: A Briefing on Positive Practice. London: LGA and ADASS.

Care and Health Improvement Programme is funded by the Department of Health and Social Care and delivered by the Local Government Association, in collaboration with the Association of Directors of Adult Social Services. The ethos within the programme is one of sector led improvement.

The web links to the webinars may be found in the resources section of this briefing.

Pawson, R., Boaz, A., Grayson, L., Long, A. and Barnes, C. (2003) Types and Quality of Knowledge in Social Care. London: Social Care Institute for Excellence.

Preston-Shoot, M., Braye, S., Preston, O., Allen, K. and Spreadbury, K. (2020) National SAR Analysis April 2017 – March 2019: Findings for Sector-Led Improvement. London: LGA/ADASS.

Preston-Shoot, M. (2020) Adult Safeguarding and Homelessness: A Briefing on Positive Practice. London: LGA and ADASS.

Quotation in Taylor, G., Price, C. and Clint, S. (2022) ‘Seen but not heard: why challenging your assumptions about homelessness is a matter of life and death.’ In A. Cooper and M. Preston-Shoot (eds) Adult Safeguarding and Multiple Exclusion Homelessness: Evidence for Positive Practice. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Quotation within a Thematic SAR on People who Sleep Rough, published by Worcestershire Safeguarding Adults Board (2020).

Quotation from the Executive and Oversight Report, published by Leeds Safeguarding Adults Board and Safer Leeds (2020), on “Understanding and Progressing the City’s Learning of the Experience of People Living a Street-Based Life in Leeds.”.

Published by Luton Safeguarding Adults Board (2018).

Within Ms H and Ms I, Thematic SAR, Tower Hamlets Safeguarding Adults Board (2020).

Presentation by Carl Price (2021) “Being homeless – How did I feel?” Presentation by Stephen Parkin (2021) “A qualitative study of the experiences of people (with experience of rough sleeping/homelessness) who were temporarily accommodated in London hotels as part of the ‘Everyone In’ initiative (March-September 2020).”

Preston-Shoot, M., Braye, S., Preston, O., Allen, K. and Spreadbury, K. (2020) National SAR Analysis April 2017 – March 2019: Findings for Sector-Led Improvement. London: LGA/ADASS.

Quotation within a Thematic SAR on People who Sleep Rough, published by Worcestershire Safeguarding Adults Board (2020)

Presentations by Carl Price (2021) “Being homeless – How did I feel?” and by Jason, John, Kinga and Tom (members of Independent Futures) (2021) “What works and what doesn’t for homelessness? A perspective informed by lived experience.”

For example, South Yorkshire Housing Association (2021) Housing First Rotherham: Impact Report 2020.

For example, Safer Arun Partnership (2019) Arun Street Community Outreach Keyworker Project.

Preston-Shoot, M. (2020) Adult Safeguarding and Homelessness: A Briefing on Positive Practice. London: LGA and ADASS.