Foreword

The work took place in a period of challenging times for both the NHS and Local Government as the second wave of COVID-19 hit communities hard during this period. This did mean that some systems were unable to prioritise this work for a short period but after the success of the vaccination programme led to reduced demand on the hospitals all the key players resumed work to improve their discharge arrangements. The programme had been intended to end in March 2021 but was extended to June 2021 to allow all the parties to complete their work on the stages of the programme. Only one of the systems felt unable to complete the programme due to a lack of capacity to undertake some of the work.

We would like to thank the professional staff in all seven health and care systems for the way in which they participated in the programme and their willingness to share the learning. This did mean that sometimes their current systems were put under scrutiny and challenge in a way they may not have previously experienced. Most of these systems rose to that challenge.

Summary

The guidance from the DHSC: Hospital discharge service: policy and operating model updated in February 2021 requires both the NHS and social care to jointly develop new ways of working on the discharge of patients from hospital that should lead to a significant change from previous arrangements. The key change appears straightforward: the assessments of people for their longer-term care and support needs should take place after they have had a period of recovery (not in the hospital). This is better known as Discharge to Assess or D2A But this apparently simple requirement does require several significant changes:

- a shift of assessment and therapy staff from the acute hospital to the community. (In order to undertake the assessments at the optimum time).

- an investment in intermediate care services in both bedded-based care and the community that will help support people’s recovery particularly, a new investment in dementia care services.

- a culture and understanding of the support that can assist older people to make a partial recovery and reduce their frailty so that they can remain in their own homes.

- a focus on the outcomes for older people rather than their length of stay or speedy discharge (though getting this right did lead to both reduced lengths of stay and speedier discharges).

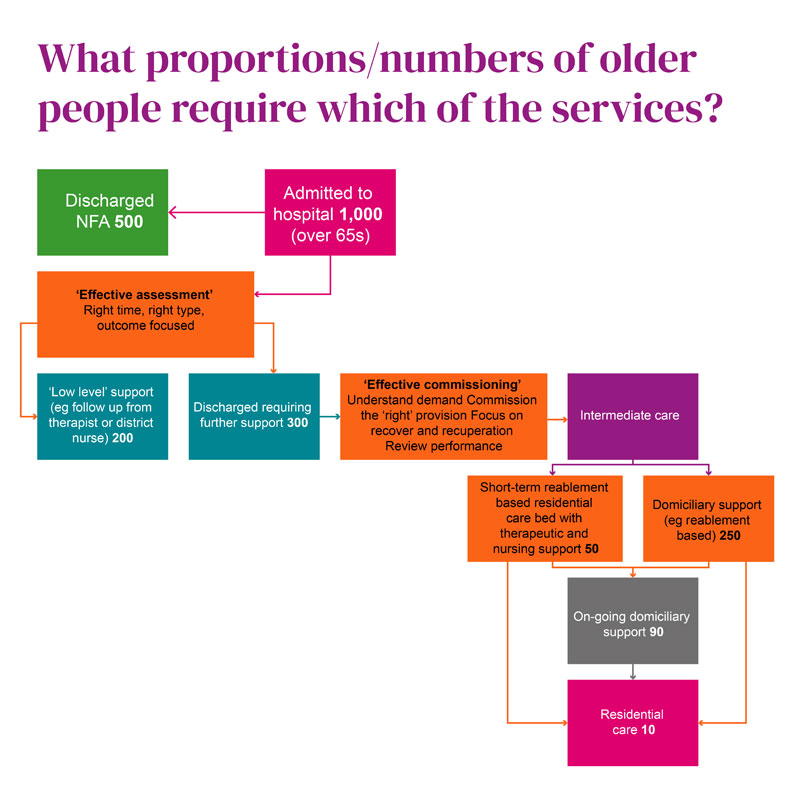

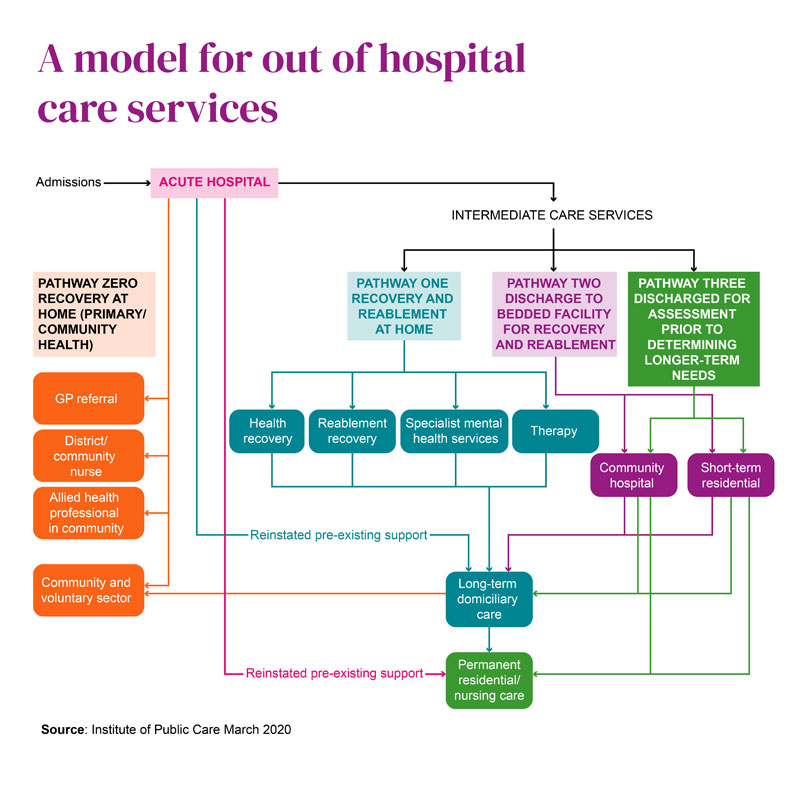

Some older people can be discharged from hospital and can either manage their own recovery safely or they can do so with the support of family or community networks. Many older people may require some additional support to help them manage their recovery – this may be in the form of health care (usually from the GP working with community nurses) or from care or support workers directed by therapists (sometimes referred to as reablement). For D2A to effectively work the NHS and local government need to jointly commission a combined set of services (known as intermediate care) in the community (including bedded facilities) into which people can be placed to support their recovery back at home. The use of community beds in this model is an interim rather than permanent admission and is intended to support a return to independence and discharge home.

This programme, which was funded by the LGA, led by Professor John Bolton, supported seven health and care communities in England to evaluate the procedures for the discharge of older people from hospital. Its main aim was to help these systems understand how to optimise the arrangements for out of hospital care and how to establish joint arrangements between the NHS and the local authority. This required a common understanding of the services they had commissioned; the likely demand on those services and the outcomes that those services were achieving in relation to helping older people return home.

The seven health and social care partners with whom this programme was working were varied in their approach. There was a common desire and recognition of the importance of working together and a growing realisation of the importance of the outcomes for the older people who were being helped. Every system had established governance arrangements through a joint board that oversaw the work on out of hospital care. This did not mean that every system was well integrated, and there were many examples where both the NHS and adult social care had commissioned services that overlapped or duplicated. The first phase of this project helped to track the services and identify their role in supporting each of the care pathways as defined in the DHSC national guidance. In nearly all systems there was an underuse of the capacity of the voluntary and community sector, and an almost total lack of community-based mental health services to support discharge to assess for people with dementia or other mental health needs.

If out of hospital care is going to focus on the benefits for older people, then both local authorities and the NHS will have to stop established practices of procuring individual beds in care homes for older people at discharge, unless there is a programme in place to help their recovery and return home. Purchasing beds in care homes does help to clear the hospital of older people who are ready for discharge, but it typically offers poor outcomes for the older people despite the best efforts of all staff involved. Positive use of bedded facilities can make a great difference for an older person at discharge, but this is only likely to occur when the initial focus remains on helping the person return home.

The most difficult logistical challenge for all systems was bringing together the health and social care data to help understand the demand and pressures on the services that had been commissioned. It usually required one person from within the system to undertake this challenging task pulling together the data from the acute hospital and linking it to the data on the services that then supported people with their post-hospital care. Even at the end of the programme some systems continued to struggle to integrate the data that would help them both understand demand on services and have clear oversight of what happened to older people moving through the hospital and community.

COVID-19 presented a significant challenge to all in the system. In fact, the pressures on the system from December 20202 to February 2021 understandably slowed down progress in this work. There were also changes in admissions to hospitals and in the needs of those being discharged which required new thinking about out of hospital care. Maintaining COVID-19-free resources to support people was particularly challenging.

Measuring the outcomes in relation to discharge to assess was the final stage of the programme and only a couple of places reached this point because of the limitations identified above (failure to be able to collect data that tracks patients). There was a particular interest in looking at the outcomes from community hospitals and the role of residential care as a place for short term recovery. Where data were available it demonstrated that the better-staffed community hospitals can get over 70 per cent of older people back to their own homes and where residential care beds were supported by therapists and nurses a similar percentage of older people returned home.

There are additional challenges for systems where there is more than one local authority looking to work with a single Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG). In many locations there is the same health provider, one or two acute hospitals, a single CCG and three or more local authorities. Each local authority tends to want to do things in their own way and many find it hard to change or adapt what they may need to do to fit in with all the other partners. There are often good reasons for this reflecting the history of local services; the rurality or size of the population; the demographic pressures; democratic influences; and multiple other factors. But this has led to very disjointed services, making it particularly hard for the NHS providers and the CCG to develop a comprehensive single system that delivers effective outcomes. Only where the local authorities can reach some agreement on how they can adapt their services to integrate with the NHS does the opportunity arise to maximise outcomes and to reduce costs. This could continue as a problem and a challenge for the new Integrated Care Services (ICS). Can local democratic wishes be set aside for the common good?

In addition to the seven health and care systems examined in this report, Professor Bolton also worked with the health and care partners in Bridgend, Somerset and North Mersey who were not in the programme but provided consistent advice and help to those systems who wanted to make changes. All three of these systems have already developed good practice in relation to integrated intermediate care services. Many thanks should go to staff in those places who were willing to help and assist colleagues in this programme.

Finally, each system was concerned about the availability and supply of domiciliary care and in several places, workshops were organised solely to explore this. The issues raised included: the restrictive over prescribing of care with little flexibility for providers; the way in which care was commissioned by councils; and the role of in-house reablement services with therapists in reducing demand. Much of the challenge was determined by the role and approach of commissioners, although the problems this generated were faced day to day by operational and front-line staff.

Those who took part in the programme recognised the enormity of the task they faced in building a better range of intermediate care services that were fit for purpose. This was accepted as the best way of introducing discharge to recover and then assess, and to improve the outcomes for older people being discharged from hospital. All the systems have now developed action plans which take them further on that journey. It is recognised that depending on where they embarked it could yet take a while to get to the desired destination.

Conclusions and key messages

This review of progress with D2A across seven health and care systems has painted a complex and mixed picture, and it is worth highlighting once again the key conclusions and messages that are emerging.

- To implement the central government requirements of D2A policy local systems need to establish a set of intermediate care services to which people can be safely discharged. This is not the situation in many places. Ensuring delivery of the best possible care pathways for out of hospital care is the responsibility of commissioners. Operational staff cannot improve the outcomes for older people without the right set of commissioned intermediate-care services where there are clear outcomes. Future guidance needs to recognise this.

- D2A requires several changes to the way the previous arrangements worked. This includes moving assessment staff (including therapists and geriatricians) out of the hospital to the community to work alongside the intermediate care services. Systems should not confuse their success in delivering speedy discharges when the COVID-19 virus hit acute hospitals with a well-managed D2A programme. This requires a shift in culture for all staff working in the NHS and social care.

- Clear pathways need to be agreed between the NHS and the local authority for older people leaving hospital, where possible this should be through jointly commissioned services. The more integrated the arrangements are, the more likely better patient and system outcomes can be achieved. A focus on better outcomes for older people also delivers shorter lengths of stay and speedier discharges as this reduces the risk of the system encountering delays because patients have no onward services to move to.

- There is scope to take pressure off Pathway 1 through developing flexible contracts with the local voluntary and community sector. In Wales, for example, a special pathway as a route out of hospital with support from the voluntary sector has been developed, and similar initiatives in using enhanced take home and settle services are known to exist more widely. There have been some discussions in England that there should be a ‘Pathway 0+’ that might encourage wider use of this opportunity for help and to support speedier discharges. There is no doubt that the voluntary sector can support with both practical and emotional help for older people on both Pathway Zero and Pathway 1.

- Health and care systems must ensure that there are a range of appropriate specialist mental health services and specialist dementia care services that can both support older people to return to their own homes (with the use of trained care professionals and assistive technology) as well as supporting more specialist bedded facilities.

- All bedded facilities should be commissioned for the purpose of recovery prior to an assessment of the older person’s needs. Although most older people will do best returning to their own homes, some will require a space for recuperation and building personal resilience prior to return home. The bedded facility whether in a care home or a community hospital should have as its main purpose the support for people to return home. Without this focus there is little prospect of Pathway 2 delivering desired outcomes and short-term placements are likely to become permanent.

- Local authorities should explore how cost- effective it might be for them to keep open packages of care for older people who are admitted to hospital, to support rapid reinstatement to facilitate timely discharge.

- The type and volume of domiciliary care available locally reflect the complex interplay of the way in which services are procured; the relationship with providers; the development of community alternatives, and the way in which care is assessed and prescribed. The key responsibility for the shape and nature of provision therefore rests with commissioners.

- The investment by the NHS in community health services is also an important part of building appropriate Intermediate Care to both address speedy and effective discharges but also helping to reduce some hospital admissions. These services need to link closely with local primary care services eg, GPs.

- All councils should ensure that their reablement-based domiciliary care services are following a therapist’s plan developed with the older person to help them regain their confidence and to support their post hospital recovery and attainment of what matters to them and their life.

- Admission avoidance is equally important in any set of intermediate care services. However, the research evidence is less clear about the best ways to tackle this. Establishing some clear measures of the effectiveness of interventions that are in place is one way to help build this evidence base. The best Intermediate care services are offering both step-up support to reduce hospital admissions and step-down support to offer speedier discharges.

- The goals for the recovery of older people leaving hospital should be realistic. Most older people want to return to their own home, but they may need to adapt to the way in which they need to manage at home. Helping people to achieve that is as important for some as helping with a full recovery which may be less realistic. In helping older people to return home health and care staff need to be fully aware of the needs of family and other informal carers.

- More work needs to be undertaken to ensure that the data that is collected is meaningful and assists commissioners in understanding the patterns of demand for their local intermediate care services. There are implications here for the type of data reporting requirements imposed by the centre.

- Health and care leaders need to jointly develop a set of measures that ensure that they are delivering the best outcomes for older people from their intermediate care services (a suggested set of measures is included in Appendix one).

- There is a challenge in how best to support continued development of D2A and intermediate care services. Many places are hoping that the Treasury will continue to support the funding for discharged patients in a way that allows the NHS and local government to make long term plans and to commission the best possible services delivering the best outcomes for older people and others at the point of discharge. It is important that local systems collect the evidence to support why this investment is worth pursuing.

Introduction

In July 2020, the LGA commissioned a piece of work to support several health and social care systems in England to look at how they might develop their out of hospital discharge arrangements. They commissioned Professor John Bolton to lead this work.

The seven health and social care systems that joined the programme were:

- Leicestershire, Leicester City and Rutland (LLR)

- Stoke and North Staffordshire (SNS)

- Bristol, North Somerset, and South Gloucestershire (BNSSG)

- Sefton

- North Tyneside

- Surrey (The Royal Surrey County Hospital and Guildford and Waverly)

- Dorset, Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole (BCP)

The programme that was established was based on the work that Professor Bolton had previously undertaken across the United Kingdom (Commissioning out of Hospital Care Services to Reduce Delays). The programme focused on the arrangements to support the recovery of older people (aged 65 plus) who were discharged from acute hospitals. The programme was planned to work with different health and care systems in three phases:

Phase one

Identifying the services that are commissioned/provided in the area to support older people discharged from hospital. To identify gaps and pressures on those services. This is a challenge for those commissioning out of hospital services.

Phase two

To count the flow of older people, over a period, to understand the patterns of demand on different services and to help identify likely future demand or to change that demand. This is a challenge for those responsible for measuring the activity and performance in the health and care system.

The image below shows the proportions and numbers of older people and which of the services they require.

Phase three

To measure the outcomes that each of the services that supported older people delivered to assist in driving improvements to the services or to decommission or recommission these services. This is a new way of looking at the services that are commissioned or provided.

The tasks ahead

Step one

Establish a group who can review the current care pathways and identify any shortages or gaps.

Understand the gaps and agree what action to take.

Step two

Establish a group who can assist in counting the numbers coming out of the acute hospital and where are their destinations.

Step three

Can we start to measure the outcomes from the system/individual service area?

Each of these phases operated independently and the systems were offered the opportunity to stop the programme at any time they thought that they were no longer benefiting from the discussions or the learning that was emerging.

The programme faced a real challenge because of the changes in practices that were necessitated in responding to the COVID-19 pandemic that hit the country. The pressure was intense for all health and care systems during December, January, and February 2020/21. However, all the participants completed the work in phase one of the programme and some made good progress in phase two. It is expected that work in all areas will recommence once the pandemic begins to subside in acute hospitals. The patterns of discharge have changed over the last year (in part related to the pandemic) – this will need careful monitoring for the future.

This report covers the period from August 2020 (when the first system joined the programme) up until February 2021. Each of the seven different systems joined at intervals during this period with LLR and BNSSG joining earlier and Surrey and Dorset the final members joining in January 2021. The key aspect of joining the programme was the need to ensure that all system partners (commissioning, operations, providers, and local support staff (performance leads) were all willing and able to participate from both the NHS and from councils (adult social care).

Key messages from Professor Bolton’s earlier work, Commissioning out of hospital care services to reduce delays:

- The services that support older people, at the point of discharge, should focus on recovery and recuperation of people who are being discharged from hospital.

- The services should be specifically commissioned for this purpose. Services that are used to support patients that are not commissioned for this purpose get full quickly (outside of a pandemic) and soon clog up the system.

- No long-term assessments for older people’s care needs (except for palliative care) should be made whilst an older person is in a hospital bed. Every individual should have the best possible opportunity to recover before they experience a long-term assessment. The Welsh model – Discharge to recover then assess is preferred.

- There should be a range of services commissioned to support older people at the point of discharge from hospital that are short-term recovery-based and therapy-led. This includes specially commissioned bedded facilities that are looking to help people get back home (including community hospitals).

- The best place for most older people to recover is in their own homes. There are four main obstacles to this:

- a lack of specialist dementia care services that support older people in their own homes.

- a lack of therapists to help reduce double handed visits from care workers by installing the right equipment.

- the over prescription of domiciliary care using the valuable capacity that is available.

- the underutilisation of formally commissioned voluntary sector services as a key partner in facilitating hospital discharges back home including in Pathway 1.

- It is important to understand the flows of older people out of hospital and into which pathway they are helped. The Newton Europe research – Why not home, why not today? found that 40 per cent of older people were supported onto the wrong care pathway – for most, on a pathway that offers a higher level of support than their needs warranted. The best area on which to focus is which older people are on Pathway 2 (bedded support) who could be supported at home and those on Pathway 1 who might be better supported with a voluntary sector support scheme such as that offered in most places but not for very high volumes of people eg, Surrey – Safe and Settled Scheme.

- If more than 40 per cent of older people being discharged from hospital require support from Pathways 1, 2 or 3, then the system is likely to struggle to cope with demands. If more than 25 per cent of these people are placed in bedded facilities the system has even less chance of coping (Commissioning out of hospital care services to reduce delays).

The image below shows the different care pathways that might be used to helped older people in their post hospital recovery. (Commissioning out of hospital care services to reduce delays, page 16, Institute of Public Care, March 2020)

The programme phases

The three phases of the work programme aimed to answer five questions:

- What is understood of the numbers of people that are currently requiring services

- What are the services that are available?

- Is there sufficient volume of these services?

- Are they the right services – should we be commissioning more services or fewer services or different services?

- Do we know which of the services we use produce the best outcomes for our patients/customers?

The learning from phase one – do we have the right services?

All the participants in this programme completed phase one. The key learning points that emerged from analysis of services available in each pathway included:

1. Different care pathways for people with similar needs

It was common for systems to have two separate care pathways for older people leaving hospital to go home (Pathway 1) - one commissioned or provided by the NHS (often referred to as a Home First service; the other commissioned or provided by the local authority (usually referred to as domiciliary care reablement-based service). There was often a lack of clarity as to which older person might be eligible for which set of services. In each place where this was the case it was agreed to either establish greater clarity on the role and purpose of each service, or to start work to integrate the services into a single model. In LLR there was a model where the NHS commissioned services took older people straight from hospital and then after 72 hours if they required more support, they were moved on to the Local Authority provided/commissioned services (reablement or domiciliary care). It also included a falls response service within two hours. This seemed to work particularly well in Leicester City. In North Tyneside discharges from hospital are co-ordinated through a single point of access, where care and health teams assess and provide support dependant on the person’s needs. There is also a first responder’s falls service that receives referrals direct from the ambulance service. The services are delivered through Care Point – a fully integrated health and social care intermediate care service. Stoke and North Staffordshire also offered an integrated response.

2. Commissioning of services from the voluntary sector

Most systems had commissioned a small volume of low-level post-hospital support from the voluntary and community sector it was recognised that this could be expanded to reduce some of the pressure on the community-based domiciliary services for both NHS and local authority. There is evidence in England (590 people's stories of leaving hospital during COVID-19) that both Age UK and the British Red Cross, as well as other smaller more locally based voluntary organisations, run excellent service (People's Stories of Leaving Hospital During COVID-19). Such evidence suggests many more people would benefit from some contact after their discharge to assist them to re-establish themselves at home, even if they don’t need domiciliary care and support, but they may benefit from a ‘take home and settle’ service and some practical reassurance. The programmes in Neath Port Talbot (Right Sizing Community Services to Support Discharge from Hospital) similarly show how the voluntary sector can offer a realistic alternative for many people to domiciliary care reablement and producing similar outcomes (Right sizing community services to support discharge from hospital). Commissioning services from the voluntary sector not only can improve outcomes for older people but also offers them a richer range of services that can help them not only with their recovery but also to regain important social links in their community.

3. Commissioning of specialist mental health services for post-hospital care

In all seven places it was agreed that the lack of mental health service involvement in either the commissioning or the provision of services for older people with dementia was a significant gap in support. The lack of a community-based specialist set of domiciliary care services supported by assistive technology often meant that the only safe route for older people with dementia post hospital was to a care home (where specialist places for older people with dementia are also in short supply). Professor Bolton referred to the very positive impact that the services developed in Bridgend could demonstrate in the work undertaken by NHS Wales (Right sizing community services to support discharge from hospital). In Bridgend, the NHS and the local authority have jointly commissioned a dementia care service that specifically helps older people with a diagnosis of dementia or delirium to return home. This is seen as a vital part of their care pathway to support speedier discharges. Stoke referred to a couple of community support services run by a mental health trust (Marrow House and Harplands Ward 4) where assessments can take place for older people with a diagnosis of dementia, and a separate service for older people with complex needs which had a focus on reducing unplanned admissions to hospital for this group which included older people with dementia. It was recognised that many of the patients who are “stranded” in hospital have mental health needs alongside other complex conditions. There is an argument to be made that older people in the early stages of dementia are much more likely to “thrive” in their own homes where at least some things are familiar. This of course needs to be managed with the associated risks. This is an example of a cohort of people who may not benefit from a rehabilitation programme but do require specialist support to help them to live with dementia in their own homes. Some places have good assessment services that can identify quickly that an older person is experiencing a level of dementia – this is not an alternative to commissioning services that support those same older people in their own homes. In North Tyneside as part of the new integrated frailty pathway they have introduced mental health workers commissioned via Age UK. These workers link closely with other staff in the community including primary, community health services and Admiral Nurses.

4. The commissioning of bedded facilities

The role of bedded facilities to support discharge, where the focus is on recovery, was a topic of much interest from the participants. During the programme, the National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) published a study on inpatient care for older people in community hospitals (Measuring and optimising the efficiency of community hospital inpatient care for older people: the MoCHA mixed-methods study). This research shows the best evidence on how to set up and staff a multidisciplinary community hospital to be most cost effective and produce the best rehabilitation outcomes for older people. It was agreed by programme participants that community hospitals can play an important role in helping the timely discharge and then the recovery of older people who are assessed as requiring bedded facilities. There was broad agreement that the 70 per cent target set by Professor Bolton for older people to return home from a community hospital was realistic if the optimised staffing (including therapists) is in place. Obviously, this is different during the COVID-19 pandemic when some of these hospitals have played a specific role in managing post-COVID-19 care.

All participants realised that if older people were placed in care home beds for the purpose of Discharge to Assess but that no therapy or other recovery-based activity was offered to them, there was a very high chance that the person would remain in the care home for the rest of their lives. The data from several sites suggested that those placed in bedded facilities (short-term) where no support for recovery was available there was a 20 per cent chance, they would return home whilst for those placed in beds where recovery programmes were supported, then around 70 per cent were likely to return home. This emerged as one of the big challenges of the current arrangements in most places. The high death rate in care homes through the impact of COVID-19 had created spare capacity in the residential and nursing sector that created potential to facilitate rapid discharge for people needing a high level of support. However, simply buying these beds may have addressed the challenge of accelerating hospital flow but did not improve the outcomes for older people unless focused therapeutic or nursing support was put in to support active recovery and achieve the goal of returning home.

5. Reinstating previously arranged domiciliary care

The role and nature of reinstated domiciliary care was also a point of discussion with the participants in some places. In some councils they keep open, for an agreed period, any package of care that was in place prior to a hospital admission so that it can be reinstated immediately on discharge. Obviously, this costs money but enables older people to be discharged quickly if they were already in receipt of care. The nature and frequency of support can be reviewed once they return home.

6. The supply of domiciliary care

The supply of domiciliary care was presented as a major issue for both Leicestershire and Bristol City Council. Each requested a separate meeting, to focus on this issue, during the programme. The focus of the discussions had three aspects:

- To what extent was the shortage of supply related to the way in which the domiciliary care was procured and the relationship with the providers of care?

- Or to what extent was the over provision of care and the prescribing of too much care in some cases leading to a shortage?

- Or was there a shortage of supply and therefore different and new solutions had to be found?

Of course, all three dimensions are contributory factors to the problems experienced in many (but not all) places in England. The limited responsibility and flexibility given to care providers was clearly seen as one problem. There is a growing view that providers should be given more autonomy to work directly with their customers to flex packages of care according to their needs. Evidence from places that have piloted models that allow older people to direct their care providers (acting as trusted assessors) on a week-by-week basis without having to resort to a care management review were explored. Evidence from the effectiveness of different ways of supporting older people who pay for their own care (‘self-funders’) was also discussed. There was also evidence shared from the work in Somerset to develop community enterprises, in rural areas, that has had a positive impact in increasing the supply of people willing to offer care in both a paid and voluntary way.

There was common agreement that domiciliary care was a valued and precious resource. This means that it must be used carefully and flexibly.

7. Reablement-based domiciliary care

All councils were either delivering or procuring reablement-based domiciliary care. Most understood the outcomes they were achieving although the very different results were not always understood. The important message is that reablement works best when it is part of a therapeutic plan to help the older person make some level of recovery related to their needs, as highlighted in research by the University of York and PSSRU, albeit now quite dated (Home care re-ablement services: Investigating the longer-term impacts). Those councils in this programme who had commissioned their reablement services from external providers often found that they had not included the importance of the therapist role in specifying these services and this then led to poorer outcomes (in relation to recovery) for service users. Councils were referred to the study of Coventry City Council’s excellent externally run reablement-based domiciliary care services included in a review of new developments in adult social care published by the Institute of Public Care.

8. Frailty strategy

North Tyneside adopted a slightly different approach to the main programme. They were keen to participate in the programme but had already developed a local integrated frailty service which was in advanced stages of implementation during this programme. The strategy was over seen by an executive team drawn from both commissioning and operational leaders in the NHS and the local authority. The programme, therefore, looked to support the evolution of the work that was already being undertaken. In essence this was part of an admission avoidance programme using the same services to those used for patient discharges.

The new integrated frailty service was based on two pathways, one for urgent responses and one for planned responses. These are delivered through a single point of access where referrals are triaged and allocated to a range of services based on the individuals needs. One key issue that participants wished to explore was the best way they could measure the progress they were making. The measures that were developed and adopted by North Tyneside are included in the appendix to this report. Links were also established between the North Tyneside Integrated Frailty Project Group and personnel in the NHS Delivery Unit in Wales who were working on similar issues. Interestingly, when North Tyneside reviewed their existing provision to establish their frailty service, they recognised the need for community mental health services and created two posts to support the work in their new designed set of services.

9. Multiple councils and multiple NHS Trusts

There are challenges where there is more than one council working in collaboration with a single CCG or single NHS provider. Each council has evolved their own way of doing things and developed their local services in a particular way which they think suits them. This does not make an authority good or bad, but it can make it very hard for the NHS to find the best way to collaborate (even less to integrate) with separate sets of services commissioned by different authorities each with a distinct set of purposes and varied outcomes. The evidence seems to indicate that out of hospital services are best delivered by a single integrated organisation, jointly commissioned for that purpose with control over a range of specific intermediate care services. The more varied the services, the harder it is to have clarity and agreement over care pathways. Perfectly competent councils working with good health services may not get this right unless they can agree on the best care pathways for local older people and commission services accordingly.

Some councils commented on the complexity of working with a range of different NHS Providers who were themselves not always operating in an integrated way – this was a common observation on the way in which mental health services failed to link with the rest of the system to support discharges. It was however notable in several places that the NHS providers of community services offered good leadership to the out of hospital care arrangements.

10. Other issues

Recovery and recuperation

During the process of this programme, several conversations took place with people who were interested in the work being undertaken but not directly involved in the programme.

One of these discussions was with Dr Andrew Marshall, a community geriatrician working in Dorset. A particularly interesting feature of the discussion was exploring the difference between rehabilitation and recovery. Dr Marshall put forward a view that for many older people who may have multiple co-morbidities, the help they are likely to need at the point of discharge is support that assists them in adapting to their life at home living with their long-term conditions.

Many older people live at home (and prefer to do so) with some difficulty but find ways to cope. This is not the same as undergoing a rehabilitation programme where a person makes a full or partial recovery. Sometimes at the point of discharge an assessment may be made that the person is unlikely to benefit from further rehabilitation. The point being made is that this is not the same as a person not being able to adapt when they return home.

One of the important features of any out-of-hospital care system is to ensure that the services are supporting people and helping with that adaptation to the new challenges they face. The evidence from Dr Marshall suggests that this help is optimised when the older person returns home to familiar surroundings, furniture, and possessions, and it is hard to replicate this in other settings.

The operational model

There was much discussion in the programme about whether the best way to establish a coherent strategy and a sustainable intermediate care service was to ensure that there was a fully integrated governance structure with pooled resources. There was a desire in some of the systems to build and sustain a single operational model to achieve this. The models run by North Mersey and Somerset were cited as examples of good practice where this was happening.

However, it was clear that the existing approach to intermediate care in most places left the services disjointed and not serving the population well. There was common agreement that the principle of a recovery-based model was most likely to offer improved outcomes leading to speedier discharges and shorter lengths of stay. There was not full agreement on the governance that could oversee this. However, Stoke and North Staffordshire which had an integrated system did demonstrate that with some fine tuning of the services on offer that they were probably best prepared to deliver a comprehensive intermediate care system.

Future funding arrangements

There was a high level of anxiety expressed in all places about the temporary nature of the current funding that was put in place by the Treasury to support out of hospital care. It is hoped and expected in all quarters that this level of funding will be continued and will be included in the mainstream funds for the new ICSs as laid out in the 2021 Government white paper: The pooled budgets that are supporting current work need to be secured for commissioners to be able to commit to the design and outcomes that the discharge arrangements require to be sustainable in the longer term.

When short-term funding is put in place to support any care system, the money can only be used for short-term fixes. It cannot be used to transform a service. Any staff taken on with the funding are likely to be offered short-term contracts, but mostly the money was used to fund short term packages of care. These may or may not have delivered improved outcomes for older people – the systems did not yet know this.

The Treasury is believed to be exploring how the D2A money was used and whether it saved any money elsewhere in the system. The only evidence that is available suggests that there have been shorter lengths of stay in acute hospitals because of discharges during the pandemic without any associated increases in unplanned readmissions of patients. There are potential savings from reduced use of bedded facilities both short and longer term, but we are not yet able to demonstrate these savings in these systems. There have always been savings made by those councils who commission effective domiciliary care reablement-based services which can reduce demands on longer term support packages.

The learning from phase two – counting the numbers of people on each pathway

Each system was keen to better understand the local demands on their intermediate care services by monitoring the numbers of older people going down each discharge pathway. To undertake this work required an ability to bring together the data from the acute hospital - which shows all discharges and their destination - with the data from the commissioned and provided intermediate care services. Each system examined one month’s activity in the hospital and tried to identify the destination of patients (over 65 where possible) at the point of discharge.

This work mostly took place in March, April, or May 2021, after the worst of the pandemic but the hospital demand was known to be different from “normal” times (reflecting a different profile of admissions and therefore of discharges). It might be of value to undertake a further piece of work to look at the different types of patients and the likely support they will need. For example, looking at the recovery-based help that elective surgical patients will need compared with those who are discharged with multiple-long-term conditions, and these might be compared against the needs of people discharged following an admission for a COVID-19 related condition.

Every system found that undertaking the data collation and analysis was challenging and difficult to achieve. In their first attempt, most systems failed to capture and gather the information on the numbers of older people who had been placed on Pathway Zero (minimal care and support). It would have required a detailed piece of work to ensure that the post codes of everyone who had been discharged could relate to a specific local authority. The data held by the NHS was generally more accurate than that held by local authorities. The current reporting requirements of situational reports (SITREPS) and do not focus on the data that systems need to gather to understand their demands and destinations. The work that Somerset NHS and local government have done on this is an excellent model for all to consider.

Every system examined the demands (as best they could) on Pathways 1, 2 and 3. In most systems, however, it was not possible to calculate the percentages of older people using each pathway (because of the lack of data for Pathway Zero). The data did however show that: most systems were making disproportionately high longer-term placements (in Pathway 3); that those on Pathway 2 were either in community hospitals or in inappropriate bedded facilities in care homes; and that the demands for Pathway 1 often outstripped the available supply of care and support. This in turn could lead to more demand being diverted to Pathway 2 where there was capacity from unsuitable bedded facilities in care homes and nursing homes. Most systems already understood (before they undertook this exercise) that they were making too much use of the wrong sort of bedded facilities that would not maximise outcomes for older people, and capturing the data only confirmed this.

At present (because of the high death rate in care homes) there is an oversupply of bedded facilities and an under supply of community-based provision. This can lead systems to placing more older people on an inappropriate care pathway for their needs. This in turn can lead to long term costs in the system and poorer outcomes for older people.

If a place wants to develop a “home-first” strategy as part of its approach to D2A then there needs to be a good understanding on what the likely demands are going to be on any community services and whether sufficient supply of those services is available when required.

One calculation to bear in mind is that on average an older person referred to a domiciliary care reablement service receives between 15 hours and 20 hours care each week for six weeks. So, for each older person being discharged from hospital to a domiciliary care service there needs to be capacity to offer a minimum of 100 hours care over the next few weeks.

This needs to be considered when the volumes of care are being commissioned. For every 100 older people being discharged home with a package of care there needs to be 1,000 hours of care available. (This calculation is based on previous fieldwork undertaken by Professor Bolton – it is important that each system understands and makes the equivalent calculation for their domiciliary care reablement services).

Phase three – the outcomes for older people

If the week by week demands on the intermediate care services are to be understood to ensure sufficiency of the right type of services, then most systems will need to do much more work on this. There were some performance leads from both the NHS and the local authority that had begun this process, working together and could now build on it.

Because of the challenges of gathering and interpreting this data it was very hard to look at the totality of the system and to determine the outcomes that different sets of older people achieved from their respective pathways.

Typically, community hospitals knew and understood the outcomes of their work and they consistently reported that over 75 per cent of Pathway 2 patients returned to their own homes. In some places the local authority domiciliary care services also understood the outcomes they achieved, although their performance varied between 80 per cent of older people requiring no further additional care and support after six weeks of care, and in some places as few as 30 per cent requiring no further support. The lower performance was generally where the independent sector was providing the reablement (at a significantly lower cost) but without the active input and guidance of the therapists to help with the recovery plans and reablement goals.

It was hard to identify the outcomes from other services, but anecdotally it was reported that people who were placed in short-term residential or nursing beds without any therapeutic or nursing support for their recovery did seem to remain long term in that bed (as discussed earlier).

If the week by week demands on the intermediate care services are to be understood to ensure sufficiency of the right type of services, then most places will need to do much more work on this. There were some performance leads from both the NHS and the local authority that began this process, working together and could now build on it.

Because of the challenge of gaining this data it was very hard to look at the totality of the system and to determine the outcomes that people gained from their respective pathways.

Typically, community hospitals did know and understand the outcomes of their work and they consistently reported that over 75 per cent returned to their own homes. In some places the local authority domiciliary care services also understood the outcomes they achieved though their performance varied between 80 per cent of older people requiring no further additional care and support and in some places as low as 30 per cent requiring no further support. The lower performance was generally where the independent sector was providing the reablement (at a significantly lower cost) but without the help and guidance of the therapists to help with the recovery plans.

It was hard to identify the outcomes from other services though anecdotally it was reported that those who were placed in short-term residential or nursing beds without any therapeutic or nursing support for their recovery did seem to remain long term in that bed (as discussed earlier).

Appendix one – measures of outcomes

A suggested set of measures to explore the outcomes from out of hospital care (discharges):

- the percentage of older people (over 65) that are supported through each pathway (Zero – 3).

- target to have 60 per cent+ on Pathway Zero.

- target of fewer than 3 per cent on Pathway 3 (include palliative care)

- the percentage of older people (over 65) who were discharged from hospital who return home on a permanent basis after 10 weeks (include those on Pathway Zero, 1 and 2 who subsequently returned home).

- target of over 90 per cent

- the percentage of older people (over 65) who were discharged from an acute hospital to a bedded facility who subsequently returned to their own home on a permanent basis.

- target of over 75 per cent

- the percentage of older people who were discharged from hospital who are readmitted back to hospital (for any reason) within 10 weeks.

- target of fewer than 1 per cent

- the percentage of older people (over 65) who are discharged from hospital and who go direct (as a new permanent placement) from an acute hospital to a residential or nursing care bed (exclude those who require palliative care).

- target of fewer than 1 per cent

- the percentage of those who return home after discharge from hospital who were on Pathway 1 or 2 who require on-going health or care support after 10 weeks.

- target of fewer than 25 per cent (this should exclude re-instated packages of care that were in place before admission)

North Tyneside – Integrated Community Frailty Programme

Measures for admission avoidance

These are a set of proposed measures which should assist with looking at the outcomes achieved by the North Tyneside Integrated Frailty Programme.

Measures of outcomes that are delivered for the benefit of the wider health and care system:

- 1. We expect to see reduced emergency (unplanned) admission of older people aged 75+ into an acute hospital from North Tyneside residents

Measure: from NHS data set

Percentage of emergency hospital admissions where the patient is 75+ - 1a. We expect to see a reduction in ambulatory visits by older people aged 75+ to the acute hospitals from North Tyneside.

Measure: from NHS data sets

Percentage of emergency hospital admissions where the patient is over 75. - 2. We expect to see a reduction in admissions to permanent care settings

Measure: from social care data set

Numbers of older people receiving care in a residential care or nursing home/ The rate of admissions to residential and nursing homes per 100,000 aged 65+ - 2a. We expect no more than 3 per cent of older people to go direct to a care home from hospital.

Measure: new data from acute hospital

Percentage of older people 65+ who are admitted to a care home direct from an acute hospital as a new admission - 2b. We expect to see a reduction in emergency (unplanned) admission for older people from a residential care or nursing home.

Measure: from NHS data set

The proportion of emergency admissions which come from care homes. - 3. We expect to see a reduction in average length of stay in hospital

Measure: from NHS data set

Number of hospital bed days - 4. We expect to see a reduction in bed days lost due to delayed transfers of care

Measure: from NHS data set (new)

Number of bed days lost in a (year) due to delayed transfers of care. - 4a. We can expect more people to return home after an episode in hospital.

Measure: from NHS data set (new)

Percentage of patients who are 65+ who return home (Pathways 0 or 1), after an admission to an acute hospital. - 4b. We expect to see reduced numbers of readmissions to hospital from patients who were discharged in the previous three months.

Measure: from NHS data set

Percentage of patients over 75 who were readmitted to hospital within three months of a previous admission - 5. We expect to see a higher level of social contact with fewer older people reporting social isolation

Measure: from social care data sets

Percentage of adult social care users over 65 who have as much social contact as they would like.

Percentage of adult carers who have as much social contact as they would like.

Outcomes from the respective services that have been established to serve the area

- 6. We expect that people referred to Care Point remain in their own home for the next six months.

New measure to be determined from local data (from Care Point)

Percentage of people 75+ who remain in their own home after contact with Care Point. - 7. We expect to see a good proportion of the older people who used the intermediate care (bedded facilities) to return to their own homes.

Measure: currently available from RQIC and NTICU.

Percentage of patients who are discharged to their own home after an admission to one of the two bedded intermediate care units - 8. We expect to see good outcomes from the domiciliary care reablement service with people remaining in their own homes.

Measure: from local data sets in ASC

The percentage of older people who are helped with reablement who require no further formal care assistance after 12 weeks. - 9. We expect that Care Call to resolve their members enquiries without the need for a hospital admission.

New measure to be determined with Care Call from their data sets.

Percentage of patients who are admitted to hospital or are taken to hospital following contact with Care Call.

Outcomes based on feedback from patients/customers

- 10. We expect to see high levels of patient/customer satisfaction levels from the services they receive.

Measure: needs local discussion as to whether the current GP/ adult social care/ secondary care measures are a sufficient proxy and whether it is worth collecting for these services separately. - 11. We expect to have high levels of satisfaction from staff working in these services.

Measure: needs local discussion as to whether the current GP/ adult social care/ secondary care measures are a sufficient proxy and whether it is worth collecting for these services separately. - 11a. We expect to see high levels of staff retention with a lower staff turnover.

Measure: needs local discussion as to whether the current GP/ adult social care/ secondary care measures are a sufficient proxy and whether it is worth collecting for these services separately.