About this guide

On 20 March 2020, the Government announced the temporary closure of all gyms and leisure centres as part of its COVID-19 response to stop the spread of infection. These leisure facilities provide vital health, leisure and wellbeing services to local communities and will be a key re-engagement service for those communities post the COVID-19 pandemic. Throughout the pandemic, councils and leisure operators have made considerable financial investments to sustain public leisure facilities during periods of lockdown and limited facility availability.

This guide follows on from the guidance note ‘Options for councils in supporting leisure providers through COVID-19’ (April 2020), produced by the local government association (LGA) in partnership with Community Leisure UK (CLUK) and UKactive. This sets out the impact of COVID-19 on leisure providers and the options available to councils to support their leisure operator through the crisis.

This guide is not intended to instruct or encourage councils to bring leisure services back in-house. It has been written to help councils in an emergency position mobilise their leisure service. It provides appropriate tools and considerations to support the internal resource that should be committed to the process. This will assist the continuity of service for the community and ease the transfer from the existing provider to the council, either as an interim measure or on a longer-term basis.

Wherever feasible to do so, councils and operators are encouraged to work together to retain the incumbent service provider, either through an open book approach or cost-plus arrangements. The additional costs of delivering public leisure services through the pandemic has impacted both councils and their service delivery partners. Both parties may be able to recoup these additional costs over the remainder of the contractual term and will be working to balance financial recovery with service provision for those sections of the community most impacted by the crisis.

While the industry has been severely impacted by the pandemic, there continues to be signs of recovery that will positively impact on a leisure service over the longer term, if the operator is able to sustain its business until then.

This guide aims to highlight the key considerations for the emergency termination of leisure management contracts. However, given the complexities of each contract and individual circumstances of a particular council that will determine an insourcing arrangement, the guide should be considered as an information source rather than a comprehensive plan of action.

The LGA encourages councils to consider (as part of the process) the longer-term objectives of the transfer, be it to retain the service in-house (via a Local Authority Trading Company (LATC)) as an interim measure until the industry has recovered, or for a longer-term. Sport England has developed a number of guidance and support materials for defining strategic outcomes, this can be found on their “capital project development” webpage. A strategic outcomes approach will ensure that decisions are made appropriate to the outcomes and ensure the strategic objectives of the service continue to be met, with the insourcing process forming part of the council’s longer-term journey and vision.

The guide is not intended to be exhaustive; councils are advised to undertake their own due diligence and seek legal, HR, tax and leisure consultancy advice, to evaluate their individual options.

Why are leisure services important?

Leisure services with their associated infrastructure play a key role in the delivery of the public health agenda through direct initiatives such as exercise referral schemes. These schemes offer low impact activity for people with a range of conditions such as muscular/skeletal disorders or rehabilitation programmes following cancer, stroke and heart conditions. Leisure services also contribute to broader statutory duties and the national objective to improve the local population’s wellbeing. Healthier lifestyles and mental wellbeing can be supported by reducing health inequalities, tackling obesity rates and physical inactivity. (Extract - LGA Guidance - Options for councils in supporting leisure providers through COVID-19 - April 2020) This can be achieved through the NHS recommendation of 150-minutes of moderate intensity activity per week, or 75-minutes of vigorous intensity a week (As recommended by the NHS) which will assist in combating health conditions compounded by inactivity.

Without the provision of swimming pools, schools would be unable to meet their national curriculum obligations, including the need for all primary schools to provide swimming and water safety lessons in either Key Stage one or two.

Losing leisure facilities or services would leave many people without access to affordable opportunities to participate in healthy physical activities. This would impact on some of the most vulnerable people in communities who have been more adversely affected by COVID-19. Besides their intrinsic value to society, the services play an important role in tackling health inequalities and social isolation, improving educational outcomes, promoting community cohesion and generating economic growth; creating jobs and volunteering opportunities and making local areas attractive places to live, work and play. They will also be essential to the recovery of individuals suffering from long-COVID, and will help our nation to be healthier and less vulnerable to the effects of future pandemics.

Councils will have a significant role to play in defining the ‘new normal’ for communities, in tackling health inequalities and delivering the ‘levelling up’ agenda5.

Maintaining business continuity for community-based leisure provision is critical post COVID-19, with many people requiring rehabilitation after suffering long-COVID, or diminished mental health caused by lockdown. The health and wellbeing of the nation is at the forefront of all our minds, and it is clear the services delivered by leisure providers play a vital role in this both now and in the future (Options for councils in supporting leisure providers through COVID-19).

Introduction

Throughout the pandemic, councils and leisure operators have both made considerable financial investments to sustain public leisure facilities during periods of lockdown and limited facility availability.

The charitable status of many leisure providers meant they could not access much of the Government financial support or the Coronavirus Business Interruption Loan Scheme (CBILS). Financial support was limited to Job Retention Scheme (JRS) and concession payments / rent holidays that were negotiated alongside any additional subsidy with their council partners.

The £100 million National Leisure Recovery Fund (NLRF) announced in October 2020 was aimed at supporting the sector to reopen, but it still falls short of the £700 million (Figure provided by the LGA. Councils currently spend £2.2 billion a year on culture and leisure services in England) needed to cover the estimated industry losses to date, with an estimated future recovery period of 18 months or more. The Government Sales Fees and Charges Schemes also provided income protection for LA facilities operated in-house, or who received an income from their operator in an outsourced arrangement.

Despite the incredibly challenging circumstances faced by leisure operators as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, we have seen only a small number that have failed to survive, largely due to the close working and support they received from their local authority partners, as well as drawing on their reserves. Others have had to withdraw from selected contracts and facilities to ensure their continued survival elsewhere.

This has resulted in councils taking emergency measures to protect their leisure facilities and services by stepping in to bring the service in-house, ensuring these essential community assets are not lost.

The guide highlights the key considerations that should be addressed when making any decision on the future operation of the leisure service, and signposts to further supporting information where this is already available in the public domain. A Transfer Checklist has been included in the guide, which sets out the range of tasks that should be undertaken when transferring the service. This can be adapted to individual council requirements. A set of frequently asked questions (FAQ’s) has also been included following stakeholder discussions, while case studies on the lessons learnt have been provided by councils that have undertaken an insourcing exercise, to share their experience.

This guide is structured to follow the main stages of the in-sourcing process:

Phase one - Decision to insource

Phase one takes place whenever due consideration is given to alternate operational models including the option to insource. There are many different motivations for councils to insource. While political opinions will feature in the decision making, due regard should be given to the financial, contractual and operational impacts of the changes that will follow.

There are many different processes that could have resulted in an informed decision to revert to an in-house operation, and these include but are not limited to:

- a leisure management options appraisal

- enacting a business continuity plan

- contingency planning review or roll out

- financial impact assessment

- contract termination.

Many of these aspects will be dictated or influenced by the existing terms and conditions which should be assessed early to assist on establishing an exit route map. Where additional contracts relevant to the arrangements also exist, such as leasing or financing agreements, they should also be reviewed. For existing charitable trusts or those with social commitments, identify the community programme commitments in place; identify if any projects are grant funded and determine if these funds are transferable. The purpose of this exit route map is to ensure that the council understands the roles, responsibilities, liabilities and contractual steps that both parties need to adhere to. This is vital to ensure the steps that follow are correct and will avoid any disputes or disagreements subsequently emerging.

This guide starts with the presumption that a properly informed decision has already been taken to insource, with the council aware of the main issues associated with this decision, relevant to their own circumstances, contractual terms and financial position.

As a minimum, the council must ensure that due regard has been given to the following considerations:

- financial impact on council budgets, and fiduciary responsibilities including Best Value

- VAT regime, and impacts of alternate models for the council

- business rate relief implications

- legal and contractual obligations (including establishing an exit route map)

- capacity to replace the operators head office functions, especially business critical functions such as payroll, finance, sales and marketing

- service continuity

- time and resource required to complete the in-sourcing

- budget for upfront costs of any new LATC set up

- governance and commissioning arrangements including client function

- staff and TUPE implications including pension liabilities

- obligations that need to be passed through to the council, such as commitments to other funders and National Governing Bodies (NGB’s)

- pension bonds and guarantees required

- impact on the supply chain

- the new role of members and avoiding conflicts of interests

- the ‘’opportunity cost’’ of initiatives that may be deferred due to the focus on reversions (such as capital investment plans)

- the communications plan – with messages for internal and external stakeholders

- evaluate current service performance and determine how the success of the new service will be measured in relation to the outcomes required.

A more detailed Transfer Checklist of tasks has been included as a reference guide.

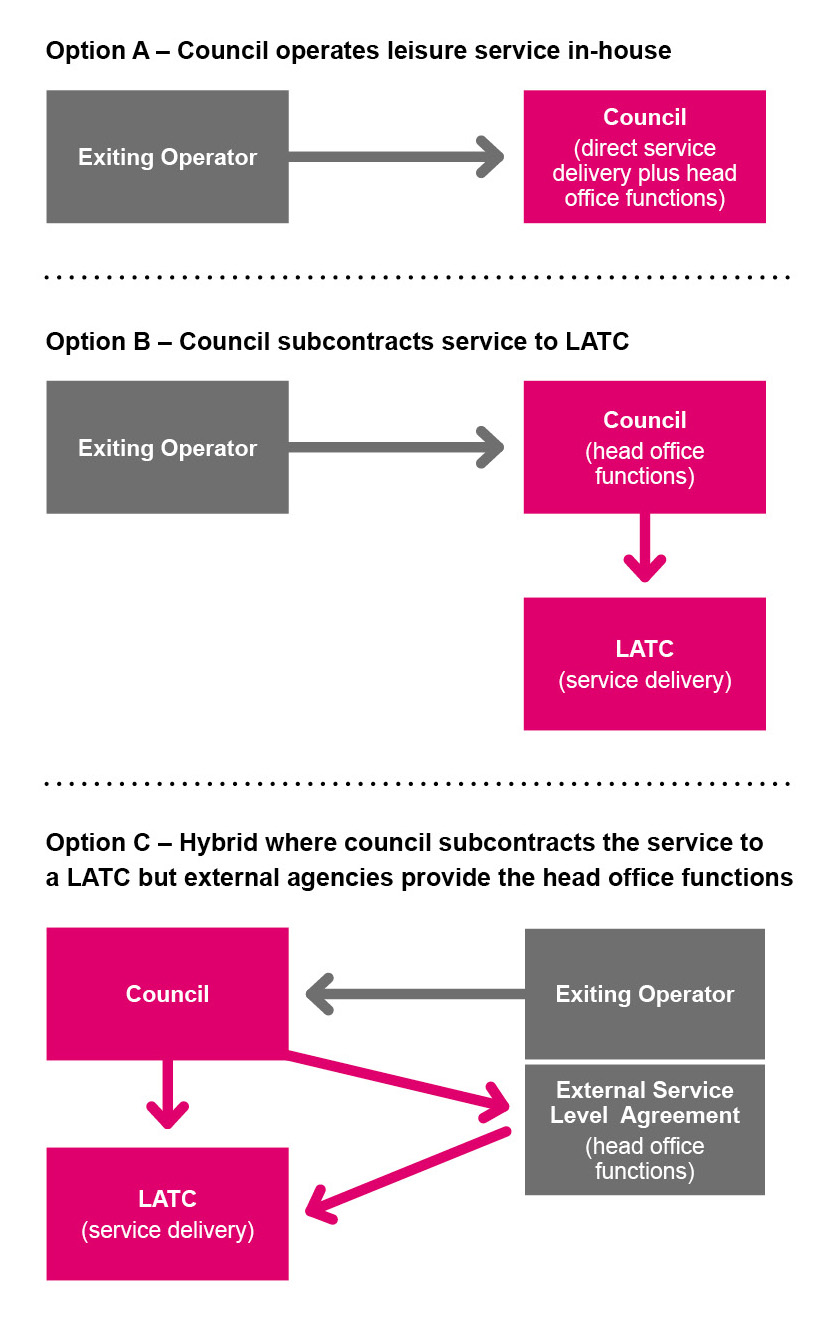

Organisational model

There are a range of alternate delivery models that could be considered in an emergency situation which are outlined in Sport England guidance. Due to the emergency timelines councils may determine there is not enough time to deploy a new local authority trading company (LATC). However, this should be one of the operating model solutions considered along with a full in-house reversion, or a hybrid solution (where professional services such as back office / support services are provided by an external organisation).

Determine early in the process if the in-sourcing is an interim arrangement for the short to medium term, or if it is the new long-term delivery model. This will help to ensure that the arrangements made are fit for purpose.

The guide assumes that outsourcing the entire service to an alternative external contractor is not an option due to the emergency timelines in play, and the requirement for a competitive tender process. There may be concerns over insufficient market interest or competitive tension to secure a Best Value outsourced solution currently, or at least until the leisure market fully recovers. Following the impact of the pandemic there may be less appetite from contractors to take on risk transfer, despite that outsourcing will continue to offer some operational flexibilities and benefits that should be reviewed as an option during the council’s deliberations.

Each operating model has its own advantages and disadvantages, so councils should determine the best fit for them. When deciding on the model, a council may wish to consider:

- the level and type of control the council wants to exercise over the service

- direct management preference or via a contracting arrangement

- the optimal VAT efficiency, including qualification for making exempt supplies. (VAT Notice 701/45)

- the ability to attract business rate relief (Only discretionary relief will be available, and it will be important to understand the councils existing relief policy and how the relief is funded (net benefit))

- what committee structures the new model will require, including the delegations to apply any reserved matters (in the case of the LATC)

- what balance will be struck between the liberty to innovate and perform, and the requirement for strong democratic oversight

- how to achieve the transition from traditional annual budget setting to a business planning culture

- what governance, reporting and contract monitoring systems will be put in place

- what access to operational information will be required

- if and how the model will achieve the strategic outcomes of the council

- the policy of the council on harmonising employee terms and conditions along with access to membership of the Local Government Pensions Scheme (LGPS).

An outline of the operational management model options with associated benefits and drawbacks is included in the Sport England Strategic Outcomes Planning Guidance.

The council will determine if the LATC, an external supplier, or the council itself will provide central support services, such as HR and payroll, direct debit runs for membership management, sales and marketing support, finance or asset management. Each element of the support service should be evaluated to determine how it is best resourced and structured in the new arrangement.

Term of new contract

Some councils may see the insourcing to a direct operation or the deployment of an LATC as an interim solution and may intend to revert to an outsourced solution when the market and competitive tensions return.

An existing LATC may be used as a stepping-stone to explore the viability of providing leisure services from this model (should such an entity exist).

A council may determine that the insourcing (in either form) is the best value long-term solution after evaluating the performance and value for money (VFM) for a period.

Legal Considerations

When an outsourced leisure contract comes to an end there are certain practical, commercial, and legal issues that need to be taken into consideration and addressed by the relevant council. These are associated principally with the ending of the existing relationship, planning the transition process and the establishment of the new delivery arrangements within the council (or LATC).

The ending of contractual arrangement with the exiting operator will result in potentially delicate issues having to be considered and resolved. Some of the issues to consider include:

- On what basis is the existing contractual relationship coming to an end: this is important to clarify from the outset. Knowing your position in the contract is vital to avoid unnecessary disputes and understand the exit obligations of both parties. For the exiting operator this may include undertaking asset surveys and dilapidation repairs; for the council compensation payments may in certain circumstances become payable; and both parties will have their respective obligations in terms of staff transfer (see further below) which will need co-operation between the two. We would advise that an exit route map is prepared early in the process to address some of these areas.

- A good contract will set out the process and steps for an exit. However even if this is the case the parties will be involved in some commercial discussions on the final terms of the exit, and such discussions will be inevitable where the contract is older or silent on exit. It is sensible to enter into a Deed of Termination recording the terms of the exit and either party's on-going liabilities (and the duration of these obligations) post the exit date.

- Where the exiting operator is a charitable trust there will be specific issues that may need to be addressed. These become more critical where the relevant trust is entirely or predominantly dependent upon the terminating contract. If the on-going viability of the trust becomes an issue, this may result in a members' voluntary liquidation and a solvent winding-up of the trust.

Financial impact

It is advisable to create an operating budget as early as possible so that decisions can be made on operating costs and income projections.

It may be necessary to reconfigure the map of accounts as it will differ to the councils' ledger system, but it is essential to retain the ability to generate accurate and timely financial information on the business activities at a profit and loss level.

Budget changes will need to be reported and reflected in the council’s medium-term financial plan (MTFP).

Set up and transfer budget

Allowances will need to be made for transfer and set-up costs that may include:

- external advisors such as HR, tax specialists, legal and/or leisure consultants

- a transfer project manager (either an internal dedicated team member or an external project management resource working full time on the transfer)

- internal officer resource from each department for the project team (part time resource, internal charges may apply)

- any breakage costs from the existing contract

- the provision of building condition surveys, and the cost of essential works identified

- any external audit costs

- costs and liabilities associated with the pension actuarial assessment

- cost of Bonds or Guarantees on pension funds, if required in the case of the LATC

- any recruitment costs from advertising or securing new senior positions via agencies

- any applicable redundancy costs (Care and advice will be required as redundancies should not be attributable to any TUPE transfer)

- new licenses cost (member management systems, website, music etc)

- development time for any leisure management system data transfer or system build

- replacement site signage (internal and external, including removing existing operator logo)

- new staff uniforms and name badges

- implementation of a new or reconfigured financial management and accounting system, or other business critical systems including CRM

- ICT infrastructure including hardware computers, printers, receipt printers, till systems, desktop licenses, independent network systems, e-mail accounts, etc

- replacement website reconfiguration or build, including online functionality to process online activity bookings, memberships and associated payment systems. Include new legislation around accessibility

- point of sale systems, including catering and retail EPOS and membership card processing

- costs associated with setting up leisure operator bank account

- stock transfer or purchase

- induction training costs

- Intellectual Property (IP) licenses or cost for creation of new brands

- production of any essential publications with new branding applied.

This list is not exhaustive, and councils should determine their own situation requirements.

While not forming part of the initial transfer cost, consideration should be given to whether the transfer is designed as a short to medium term solution. If it is an interim solution another budget may need to be reserved for a future procurement process, whenever that may be.

Phase two - Transfer preparation

To prepare for a transfer there are fundamental tasks that should be undertaken.

Determine asset condition and ownership of equipment

This may include preparation of condition surveys, asbestos risk assessments, reviewing the maintenance and lifecycle plans to determine any work outstanding and the cost to complete these works. This assessment may form part of the exit negotiation with the exiting operator and will allow the council asset management team to prepare for the future management of the assets.

Identify who owns the equipment on the inventories and ensure that the inventories are up to date. Determine if equipment is leased or owned and when will they be due for renewal. Produce a list of equipment owned by the exiting operator to determine if there is a need to purchase these items as part of the transfer arrangements.

Operating policies

Undertake a health and safety audit to ensure the systems are up to date such as risks assessments and operating procedures. Statutory inspection logs should be reviewed to ensure the annual inspections have taken place and that any required remedial works have been completed. This audit should identify the health and safety competent and qualified personnel in each centre.

Staffing

The exiting operator should provide the council with a TUPE transfer list (legally the employee liability information does not have to be provided until 28 days before the transfer, unless there are contractual provisions that say something different). On receipt the council should undertake a HR review on lines of reporting, structures, pay and benefits.

A gap analysis will help to identify any measures that the council will need to advise the incumbent of, but also to identify differences between the TUPE cohort and any new staffing structure or requirement. This can also be used to develop an enabling plan. Transition will happen before transformation, so setting out a one to two-year plan from the outset provides a clear direction of travel.

Identify which senior personnel will transfer across and determine how the contract would be managed, monitored and supported on a day-to-day basis.

Identify any recruitment requirements for any new structure along with any loss of central services where these cannot be absorbed into the existing council structure. Central services would include HR and payroll, finance, membership management, ICT, sales and marketing functions as well as asset management. Even if ‘assigned employees’ are not required by the council going forwards, the employees would have the right to transfer and then the council would have to make changes to the structure. It could rely on the ETO defence i.e. an economic, technical or organisational requirement entailing a change in the workforce defence to any TUPE related dismissals.

It is advisable to complete a risk assessment on the status of casual workers (as defined by the exiting operator) to ascertain whether these individuals are casual or may in fact be employees.

Policy decisions may be required on a range of staffing matters including:

- requirement to harmonise employment terms with those of the council (required for a direct council operation, but may not be required when a LATC is deployed, the law and its interpretation changes over time and specialist HR / Legal advice may be required on this matter)

- particular consideration should be given to pension terms, the use of an admitted body scheme (ABS) or local government pension scheme (LGPS) scheme and if this is ‘open’ or ‘closed’

- whether the use of casual workers (zero hours) will be acceptable (there may be very significant cost implications if the incumbent operator makes extensive use of causal workers / zero hours contracts)

- whether non-contractual staff policies are adopted

- whether there will be continuation of benefits not usually applicable under council control, such as bonus payments and other performance incentives.

Specialist HR advice may be required in a more complex TUPE transfer.

Pensions

On receipt of a TUPE list, an actuarial assessment will need to be commissioned with the co-operation of the exiting operator. The main requirements will include;

- determining the fund deficit / surplus attributable to the exiting operator

- identifying exit liabilities, including deficit funding and whether there is a risk-sharing mechanism in place under the contract for services

- requirements for the council to provide bonds / and or guarantees (in the case of the LATC)

- providing the employer's contribution for the admission of the TUPE cohort

- estimating the relative cost of a closed and open agreement, and risk assess the option for a closed pension agreement (in the case of the LATC).

In some cases, the fund may require the deficit to be crystallised as a result of the termination of the LGPS admissions agreement. This could be an initial expense for the council, depending upon the terms of the contract for services.

If the LGPS is open to new employees as well as transferring employees, there may be a greater cost implication compared to the exiting operator arrangements in place.

If, in respect of a LATC, participation in the LGPS is not extended to new employees, this will minimise the ongoing cost to the council. It is possible for the LATC to restrict admission to the LGPS for those new employees it designates as eligible. This will mean it will allow only a limited number of future admissions. The LATC will need to establish a qualifying automatic enrolment pension scheme for those new employees not eligible to join the closed scheme, and for it to agree the employer’s contribution rate payable.

Business Planning

The exiting operator will have applied the disciplines associated with the business planning process, and it would be advisable to continue with the production of a comprehensive annual business plan rather than rely solely on the traditional council budget setting process.

In the case of the LATC, the approval of the annual business plan will form a key part of the governance and monitoring structure.

Commissioning and contract management

Even though the council will have more control over the service, either from operating directly or through a LATC, it is advisable to have formal agreements in place to define the respective responsibilities and allocate risks to each party. Agreements also provide continuity towards professional standards (and can support the transition process to re-procurement should the LATC be intended as an interim measure).

It is important to retain service objectives which can be determined by undertaking a strategic outcomes planning process as recommended in Sport England Strategic Outcomes Planning guidance. Consideration could be given to additional service outcomes that could be built into the new arrangements that are aligned to the councils’ strategic objectives.

The recommended contractual documents (excluding any governance documents for the LATC) are:

- service agreement (the contract)

- lease or license to occupy

- service specification to include service outcomes, reporting and key performance indicators.

Additional guidance and templates for the subcontracting arrangements can be found within the Sport England procurement toolkit.

It would be beneficial to extract from the contractual documentation the key conditions of the business relationship and to include this within the new organisation’s Business Plan, for ease of reference.

The contractual documentation suite for the formation of the LATC itself will also need to be prepared and may include a shareholder agreement, financing documents, director employment conditions and other corporate procedural documentation.

The LATC will require as a minimum:

- Health and Safety Policy and procedures

- a business plan (annual production and approvals cycle with the Council)

- cash flow projections

- staff policies and procedures (including grievance and disciplinary)

- clarity on any non-statutory policies that may be adopted from the exiting operator

- standing orders and scheme of delegation

- appropriately qualified health and safety advisors

- external auditors

- directors indemnity insurance

- other systems and documents required by company law.

Performance management

A new Service Specification should be created which can be aligned to the existing arrangements with any additional requirements built in to reflect the new service outcomes. This is an opportunity to re-align the service to the councils’ current priorities and strategic objectives such as:

- access and equality tracking

- protected programme time for under-represented or target groups

- accessibility policy to protect concessions, ensuring cost is not a barrier to participation for those who would benefit most

- social return on investment / social economic impact measurements

- joint health initiatives, such as exercise on prescription and social prescribing

- resilience planning, such as outdoor facility design and infrastructure for any future lock downs

- Moving Communities– monitoring and tracking regime.

A new reporting regime will need to be developed that is appropriate for the arrangement chosen, either direct operation or via the LATC. This will include allocating monitoring personnel and determining the monitoring frequency, identification of key performance indictors (KPI’s), reporting requirements and quality assurance systems, which will have been updated to reflect COVID-19 management regimes.

The new Moving Communities framework by Sport England tracks participation at public leisure facilities and provides new evidence of the sector’s performance, sustainability and social value. This data will assist local authorities, leisure providers and policymakers to support the recovery of public gyms and leisure centres, taking informed decisions to keep our nation active.

Data transfer and Intellectual property

It is not uncommon to find that the existing contract is silent on who owns the membership and customer data. More recent contracts in the Sport England procurement toolkit set this out, but even where there is an agreement to transfer the data, there will be a variety of General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) considerations and constraints. In particular, the transfer of customer data from the exiting operator to the council is not a business-as-usual activity. As such it may not be a data processing activity that leisure operators cover in their privacy notices given to customers. If this is the case, the exiting operator should give specific notification to customers that the transfer is going to happen. Cooperation with the exiting operator will be needed during this process.

Once the customer data has been received, the council will be the data controller of that data and will need to ensure it acts in compliance with the Data Protection Act (DPA) 2018 and UK GDPR. Since it will be acquiring a new dataset, the council should conduct a Data Protection Impact Assessment before the transfer is made so that it is prepared to put in place compliant procedures once the data is received. Activities following the transfer should include setting up processes for notifying customers that the council is now the data controller (with a relevant privacy notice) and reviewing the data received to ensure it is accurate and up to date.

Where a contractor's intellectual property (IP) has been used in the delivery of a contract, the council will need to consider whether it requires ownership of that IP (or at least a licence to continue using it) once services are back in-house. This is often the case where a local trust has been set up to run leisure centres and that trust has developed a particular brand or bespoke product. If the council wants to carry on delivering the services under that brand or using that product, the right to use the relevant logos and other materials needs to be secured. The existing contract may deal with the treatment of IP on exit, but this is not always the case.

Governance for LATC

Any new LATC created will need an appropriate governance framework in place, including directors who will be responsible for the day-to-day operation of the company. The council should consider the number of directors, any specialist skill sets wanted and where they are recruited from. If these directors are officers or members of the council, consideration should be given to conflicts of interest. Often there is a shareholder committee in place, which acts as the body that opines on the reserved matters set out in the shareholder agreement (and other matters), and acts as part of the council's governance mechanisms. This will be in addition to the normal governance structures that are used in the relevant council.

From a governance perspective, the council will also need to consider the powers it is relying on to enter into the arrangement, subsidy control and issues relating to corporate form. A LATC can take various corporate forms such as a company limited by shares or guarantee. The eventual form will in part depend on the future aspirations of the council.

Notwithstanding that a company owned by a single shareholder does not require a shareholder agreement; it is advisable to have one in place as it enhances satisfaction of the Teckal conditions relating to control. The shareholder agreement will often include a list of reserved matters which are key areas of activity that cannot be undertaken by the company without the consent of the shareholder (ie the council).

Phase three - delivery

Once formal approval for insourcing has been secured, the delivery and transfer stage will begin (though some progress on these may have already been made through the preparation phase).

Project plan

A detailed mobilisation plan should be created using the Transfer Checklist provided in this document as a starting position and adapted as needed.

An issues log is an essential document that is kept up to date throughout the transfer process, evaluating each task status against a risk and likelihood rating and identifying the project team member responsible for completing each task and by when.

Project initiation and governance

Good practice needs to be applied to include the following;

- create a project initiation document (PID), including the target date for transfer

- identify the project owner and sponsor assigned (tier one or two officer if possible)

- create a risk matrix, with impact assessment and mitigation strategies (the exit route map created upon review of the existing terms should inform this)

- establish a project board, frequency and terms of reference defined (recommend weekly project team meetings)

- task and finish groups can be established, depending on the scale of the transfer this may involve a:

- demobilisation team

- mobilisation team - the escalation of issues process should be defined

- delegated authority is identified in case of absence and emergency decision making

Having broad delegations will help with delivery and this should extend to;

- spend approval levels for external resource and project costs

- appointment of officers to the Project Board and Project Team

- determining the form and function of the LATC where applicable

- company formation and registration where a LATC is deployed, including delegation for the founding director.

Project team

Members of the project team should be identified as early as possible in the preparatory stage, and they will report to the project board. It is important to emphasise that the team members are going to have to deal with a high volume of work and they must allocate time for this, even if it means reprioritising existing workload. For the duration of the project from decision being taken to transfer each project team member may be required to spend between 20 per cent and 50 per cent of their time on the project.

This would usually include:

- external advisors (and/or PMO lead)

- head of service (relevant service head if no leisure client function exists)

- HR and payroll

- finance (credit control, membership, management accountant)

- operational representative from TUPE cohort

- procurement / suppliers manager

- sales and marketing

- ICT

- Property and asset team

- health and safety / operational lead.

Phase four - post transfer

By setting up the infrastructure, process, systems and personnel outlined in the guide and by utilising the Transfer Checklist to work through tasks, transfer progress should be made at the required pace to achieve the target transfer date.

Following transfer there will be a period of settling in for operational staff employed to deliver the service, and the providers of the head office support services. During this time efforts should be made to introduce the monitoring and reporting programme, to set the standard for the service moving forwards and to enable the key personnel and council interface teams to get into a pattern of information transparency and cooperation.

A formal review of the transfer process should take place to capture any lessons learned to aid any future transfer if the service is to be outsourced again at a later date.

Lessons learnt

As part of the production of this guide stakeholder interviews took place with councils that have already undertaken an insourcing process, either to the council direct or to a LATC.

Several common themes emerged on the lessons learnt along the way, these have been collated below as advisory points for other councils in a similar situation to consider:

- Exhausting all options to maintain the existing operator: explore terms that could make the existing contractual relationship more viable, perhaps consider new contractual measures that will allow the council to have more influence over the service without being the controlling entity. This includes securing key performance data to help inform decision making. Identify the root cause of the previous contractor failure to ensure that any new arrangement being put in place does not repeat the same failure situation. Monitor performance against industry benchmarks using the new Sport England Moving Communities platform, the national benchmarking service or UKactive research institute for industry recovery rates and benchmarking.

- Taking careful consideration before deciding on a temporary or permanent measure: evaluate the new service objectives and strategic outcomes required before a decision is taken on whether the insourcing is temporary or permanent. Aspirations for the future of the service may change in line with the industry recovery, and budgets could recover longer term with an external operator in place again.

- Ensuring there are strong project management processes in place: be aware that once the decision to insource has been made the process takes on a life of its own and you cannot stop it, so ensure sufficient time is spent during the preparation stage. Ensure there is a full-time project manager (PMO) overseeing the process and capturing actions and updates as this will be a full-time job where the process needs to take place quickly. Get your project team together early to understand what needs to happen, the timelines and what their own remit is. Members of the project team need to accept the responsibility being handed to them and act accordingly. Multiple work streams need to be delivered in parallel, so each department needs to work together at pace to deal with tasks that cross over multiple departments.

- Understand the delegations and who makes the decisions: if you only have a small window of time with them come prepared with a list of decisions that need to be made each week, to make that time most effective. Set out a hierarchy of decision makers, so if one isn’t available the next on the list can be utilised.

- Do not assume the transfer will complete fully or on time: create a risk assessment or issues log and keep it updated at all times, this will help the PMO track any issues before they escalate by logging progress against each task and measuring the impact and severity of tasks not being completed on time. Always find workarounds to problems as they will arise, as the transfer will not be seamless. A fully completed transfer may not happen; some aspects of the service may need a workaround for a period of time until they can be properly absorbed into the new service, not all suppliers will meet the transfer deadlines, so explore acceptable solutions.

- Look after the transferring staff: They can get demoralised quickly through a transfer and can make the process smoother for colleagues and customers if they are on board with the process taking place. Keep transferring staff updated on progress as much as possible. Nominate staff representatives in each centre to escalate concerns to the HR team as they arise and to feedback updates on the process.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to all the people who contributed to the making of this publication:

Amardeep Gill, Partner, Trowers & Hamlins

Andrew Durrant, Executive Director of Place Services, The Royal Borough of Windsor and Maidenhead

Chris Donkin, Facility Lead, Sport London

Councillor Titherington, Deputy Leader and Cabinet Member (Health, Wellbeing and Leisure)

David Scott, Head of Communities; the Royal Borough of Windsor and Maidenhead

Helen Hull, Commercial Advisor, LGA

Ian Leete, Senior Adviser – Culture, Tourism and Sport, LGA

James Barnes, Parks and Countryside, Sheffield City Council

Jane Wilson, Leisure and Community Manager, Cambridge City Council

Joanne Martin, Managing Director, My Leisure Consultant

Karen Whitfield, Head of Service, South Kesteven

Kevin Mills, Director of Capital Investment, Sport England

Kirsty Cumming, Chief Executive Officer, Community Leisure UK (CLUK)

Lisa Bowes, Partnership Officer, Sheffield City Council

Louis Sebastian, Senior Associate, Trowers & Hamlins

Mark Lester, Director of Commercial and Property, South Ribble

Martin McFall, Partner, Trowers & Hamlins

Michael Berrington, Programme Director, Local Partnerships LLP

Neil Anderson, Assistant Director of Projects and Development, South Ribble

Paul O’Brian, Chief Executive, APSE

Paul Walker, Operations Coordinator - Education, Leisure and Life Long Learning Directorate, Neath Port Talbot

Rebecca McGuirk, Partner, Trowers & Hamlins

Samantha Dunker, Commercial Projects, Sheffield City Council

Samantha Ramanah. Adviser – Culture, Tourism and Sport, LGA

Simon Jones, Cultural Services Manager, Hinckley and Bosworth Borough Council

Stefania Horne, Head of Parks and Sport, London Borough of Hounslow

Steve Laird, Senior Consultant, My Leisure Consultant

Steven Scales, Director of Membership and Sector Development, UKactive

Steven Welch, Strategic Lead – Leisure Operations, Sport England

Stuart Lockwood, Chair, Community Leisure UK (CLUK)

Tina Holland, Programme Manager – Procurement, LGA

Tim Webb, Leisure Contract and Capital projects Delivery Manager, Exeter City Council

Appendix A: Frequently asked questions

Included below are a series of questions commonly asked by councils that are intended to assist in supporting the conversation between organisations. The answers are provided by the consultants following stakeholder engagement with organisations having been through an insourcing process or currently undertaking a review for insourcing.

Appendix B: Transfer checklist

The following checklist provides a list of action that councils should consider as part of their transfer process. This list is not exhaustive, and councils can adjust to suit their own individual requirements.

Download the transfer checklist (word document)

Appendix C: Case studies

Exeter City Council insourcing case study

The challenge

Exeter has six sites that were operated by Legacy Leisure along with a new £45m Passivhaus leisure centre that was due to open in 2021. The existing contract was coming to an end and a new procurement process started September 2019. Several bidders were shortlisted at SSQ stage: the incumbent was not one of them. After the first national lock down (March 2020), the council checked for continued interest from bidders but did not feel confident of any organization’s viability. The procurement was subsequently abandoned April 2020.

While the council used an open book approach to maintain the financial support package for the incumbent, retaining an operator on this arrangement indefinitely created financial risk. As the existing contract was coming to a natural end and having determined there was no longer appetite from other operators to take on risk or invest capital in the new centre fit out, the council decided an inhouse arrangement would be preferable. While recognizing the in-house service would be more costly by comparison to an external outsource, the council had more comfort in this option as they could budget for the calculated costs. An exit settlement was agreed with the incumbent a month prior to the contract end.

Due to the timing of the operator exit the council was left with responsibility for implementing COVID-19 safety procedures which meant the Exeter sites opened a month later than other centres across England, at the end of September 2020.

The solution

The insourcing process was supported by an external operational specialist three days a week, M&E consultants were engaged, there was internal HR support and external HR consultancy which cost circa £25K in total. Finance and legal support were secured inhouse.

Post transfer a restructure is taking place to align roles with the new service requirements. While the job evaluation process was unsettling staff are now happy and settled. The Sales and Marketing functions now come under the existing central marketing team that supports tourism in Exeter, while the finance team have absorbed the additional work.

The impact

The council started with a low membership base, as 60 per cent of members had left during the pandemic. A revenue budget of £1,542,130 was agreed to cover the cost of transfer and re-launch the service. An additional £270,000 was allocated to cover the cost recovery agreement with the incumbent operator. £330,000 of Capital budget was allocated to reopen the centres in a COVID-secure manner. The actual spend was £845k less than budgeted. This was down to several factors but principally the further lockdowns which reduced operating costs and provided access to the job retention scheme (JRS) payments.

The new £45m St Sidwells centre is due to open late 2021, with refurbishments at Riverside complete by Summer 2021 (pandemic delayed construction). It is anticipated these new developments will contribute towards reducing the new service subsidy with projections of break-even or possibly a surplus being made from 2023.

How is the new approach being sustained?

Post transfer the team is in a period of consolidation. Political and executive support remains positive. Leisure support services have been largely absorbed into the existing council departments. Monitoring is not yet in place.

The decision has been made not to outsource again in the future. When the disruption from transfer has settled the council may consider an LATC model to assist with managing the council partial exemption threshold.

Lessons learned

Ensure any council considering insourcing have operational knowledge leading the process or recruit this knowledge to support the transfer. Decisions need to be made quickly as the pace of transfer is fast, so ensure there is senior management and political support for decision making. Win the hearts and minds of transferring staff as they will reassure customers and support the process. The council made an active choice to bring the TUPE cohort inhouse and to offer staff council terms and conditions which was used to positively promote the process. Have confidence in the transferring staff – they know what needs to be done, so empower them in the process.

Contact: [email protected]

Hounslow insourcing to LATC

The case study outlines the council reversion of the leisure operation from Fusion Lifestyle to a newly established subsidiary Lampton Leisure (a LATC) of Lampton 360 (an existing LATC). It captures the challenges faced and how they were overcome, and includes valuable lessons learned from the London Borough of Hounslow council.

The challenge

The council felt that the service needed to be re-aligned to the long-term wellbeing objectives as set out in the corporate plan 2019-2024. Following an options appraisal, transfer into the council’s wholly owned company was deemed the best long-term solution to achieve these and other strategic objectives.

The solution

A mutually agreed early contract termination with Fusion Lifestyle, with reversion of the leisure facilities to council management via a newly established leisure LATC (Lampton Leisure); a subsidiary of the existing LATC (Lampton 360). The full transfer involved six leisure facilities (to the LATC), four public halls and a day centre (to direct management by the Council).

The Cabinet agreed the transfer on 8 September 2020, supported by an options appraisal. Once the decision was taken to transfer the leisure services to an LATC, the transfer was achieved within 8 weeks. Despite the additional complexities caused by new COVID-19 management regimes on re-opening, the transfer was achieved on 1 November 2020.

The impact

The options appraisal identified the best model as a transfer into the council wholly owned company to maximise the financial benefits and to bring added value to the council and its residents.

A mobilisation budget of £400,000 was approved; most of this budget was required for technology, asset repair costs, brand and associated set up costs. Support resource for leisure and project management costs was less than £100,000 which included leisure consultancy and project management costs between the LATC and the council.

The council’s objective was to deliver the services for no higher a cost than when outsourced.

How is the new approach being sustained?

An effective but light touch client function that focuses on the strategic outcomes and partnership working is in place.

Lessons learned

Specialist leisure and project management support was provided to the project board in the form of a PMO; alongside other specialist advice such as legal and transitional sales and marketing support.

The complexity, time and effort required to achieve the transfer must not be underestimated. The project had to deal with several challenges: demobilization, transfer, and mobilization of a new service in a new entity under a wholly owned company.

Governance structures and having clear strategic objectives were critical and were put in place from the project commencement, with project ownership and oversight by the executive director. Bringing the right team together across a range of functions to support delivery was important. The project team included leisure, communications, HR, legal, finance, procurement, corporate property, facilities management, digital and ICT and customer services.

Leisure expertise was essential throughout the project. This aided the loss of knowledge whilst the transfer was taking place and supported the new entity set up. Other areas of expertise that were brought in focused on sales and marketing functions, web and the use of multi-channel media.

Delegations were given through the cabinet to officers, to achieve the project objectives. This enabled quick actions and flexibility throughout the process.

ICT and GDPR issues were complex; system reconfiguration takes time which needed to be factored into the project planning.

Investment in the right support team was key to the success, this enabled officers to identify the risks ahead of time and design solutions.

Advisors need to work with the officers to apply local knowledge and to provide confidence in the navigation of multiple workstreams.

The emerging management team from the LATC / council need to be immersed in the process from the beginning, taking ownership of the shared objectives. The early transfer of a manager from the incumbent operator helped with logistical issues around the transfer.

All of the above contributed to the success of the transfer alongside the effective teamworking at all levels that enabled a quick delivery.

Contact: [email protected]

South Kesteven leisure insourcing

The challenge

The council have four centres that were operated by 1Life. Prior to the end of the contract term the council initiated an options appraisal. The preferred route at that time was to extend the current contract arrangement for 15 months to allow time for an external operator procurement process. COVID-19 happened and the council recognised that the market appetite had changed.

A risk assessment of the situation forced the council to reconsider the alternative options. One of these was the creation of a LATC which had not been selected originally as all risk would remain with the council and it was recognised there would be high set up costs. The decision for this went to cabinet August 2020 and secured approval.

The solution

Leisure consultants supported the original leisure options appraisal while legal counsel was received on the structure and creation of a new company, along with external tax advice on how to protect the council’s VAT exemption.

With only four months left on the existing contract the setup of Leisure SK Ltd (the LATC) and the transfer needed to take place by 31 Dec 2020. It was a significant project which was supported by the chief executive and leader and involved weekly meetings led by the council project team.

The staff transferred into the LATC with their terms and conditions intact to future proof a possible outsource again in the future.

The impact

£500,000 was allocated for the transfer and set up of the LATC £420,000 has been spent and the remainder rolled over to new financial year.

The service costs more than before the pandemic, but less than the period of national closures. There is a five-year trading plan in place projecting a small profit from year two.

How is the new approach being sustained

The feedback on the new service so far from customers and the council’s Scrutiny Committees has been good. Karen heads up the monitoring regime which is a two-sided process with a balanced performance scorecard.

Lessons learned

Timing can trip you up, transfer arrangements differ between tasks and some need more time than you have, so you have to adapt; for instance, the transfer of data and set up of the leisure management software with Gladstone took four months. The bank account took some time to be set up which delayed the setting up of suppliers. Transferring staff were consulted with very early on, to inform them of what was happening and to gain confidence and support for the transfer. Employee representatives were established, and regular zoom calls took place on any key staffing issues as they arose.

Contact: [email protected]

Links to publications

While there are several resources linked within the body of the guide, the following section contains existing publications that may also assist councils.

LGA - Options for councils in supporting leisure providers through COVID-19

LGA – Leisure under Lockdown: How culture and leisure services responded to COVID-19

LGA – The impact of COVID-19 on culture, leisure, tourism and sport

LGA - Website accessibility requirements

APSE – a Guide to Bringing Local Authority Services Back in-house

APSE – Rebuilding capacity for insourcing The Case for Insourcing Public Contracts, May 2019

Central Government Guidance - The Outsourcing Playbook

Guide on Service Delivery, including Outsourcing, Insourcing, Mixed Economy Sourcing and Contracting, June 2020

Central Government Guidance - Guide to assessing economic and financial standing of Bidders and Suppliers, December 2020

Central Government Guidance - Financial Viability Risk Assessment tool to assess supplier financial security

Central Government Guidance - Corporate financial distress, July 2019

Provides basic understanding of corporate financial distress for individuals engaged in the management of Government supply contracts

Community Leisure UK – Benefits of using a Trust model, Value of the Trust model and Impact of the Trust Model

Health and Safety Executive – Guidance documents

Sport England provides overall support on facilities and planning

Sport England Strategic Outcomes Planning Guidance (found on the capital project development webpage): Provides a strategic approach to sport and physical activity that supports local priorities

Sport England – Procurement Toolkit (found on the capital project development webpage): Provides an informative guide to leisure procurement options and procedures to follow, and provides good practice templates for councils to use and adapt as needed. The toolkit places importance on achieving local outcomes, which aligns with the aims of our new 10 year strategy Uniting the Movement.

Sport England Moving Communities platform

Moving Communities has been invested in by Sport England to provide a data platform that tracks participation at public leisure facilities and provides new evidence of the sector’s performance, sustainability and social value at a scale not achieved before. This data will assist local authorities, leisure providers and policymakers to support the recovery of public leisure provision and help informed decision making locally to keep local communities active. If a Local Authorities would like to sign up to the service, or find out more information, please contact Alison Rivers at Leisure Net. ([email protected]).