Foreword

The Government and councils are united in their commitment to help more people switch short car trips with safe and convenient walking and cycling journeys. More active travel and fewer car journeys reduces pollution and increases levels of exercise to improve public health. Less traffic also reduces congestion. To promote further action the Government introduced a step-change in its active travel ambition in ‘Gear Change: a bold vision for cycling and walking’ with £2 billion in new funding by 2024 to deliver on its aims. This urges councils to go further and faster to increase walking and cycling. This will involve some initially controversial decisions, in the reallocation of road space from cars. Low-traffic Neighbourhoods (LTNs) are a high-profile example of this kind of policy that polarises opinion in many quarters.

Last summer many local authorities implemented active-travel schemes to help with social distancing restrictions during the pandemic, incentivised through the then Emergency Active Travel Fund (EATF). The initiatives that came under the EATF took place in extremely challenging times for local authorities where the usual approach to public engagement was not possible or intended by Government. For many areas, changes have been quickly embraced. For some others, the changes have caused tension between different communities and sometimes bruising disputes with residents and other stakeholders who opposed the measures and critical of the process in which they were delivered.

As a country, if we are to meet our Net Zero ambitions, we will all need to change the way we currently travel, reducing our dependency on cars, and given that road capacity is largely fixed, this means there will be disruption to the way most people are accustomed to travel. The diversity of experience from last year provides useful lessons for local government as we emerge from the pandemic and contemplate the pressing challenge of transport decarbonisation and the Government’s ambitious plans for walking, cycling and more recently, bus services.

To help draw out some of the key lessons from the EATF programme, the LGA commissioned experts from the University of Westminster and Fern Consulting to undertake independent research. They spoke to a range of councils, held focus groups and consulted experts. The findings they have produced are not intended as formal LGA guidance, but to show how different approaches to engaging communities, especially residents, appears to have influenced the extent and nature of opposition experienced in case-study areas and elsewhere. The research explores the longer-term relationship between these councils and their communities and what councils do (or don’t do) 'in the moment', offering practical recommendations concerning the management of disruptive change.

The rate and intensity of ‘disruptive change’ on our roads is only likely to increase over the next few years. In order to manage this change, councils will need every tool available to balance the needs of road users, local communities and the needs of the environment. We hope this research provides some insights into achieving this.

Cllr David Renard

Chair of the LGA’s Economy, Environment, Housing and Transport Board

Introduction

Active travel and health have been top priorities in policy agendas for some time now. But we have seen during the past year how the COVID-19 pandemic has urged us to rethink mobility in our towns and cities. Across the country, councils have accelerated the transformation of our streets to facilitate much needed safe, active and more sustainable forms of travel. Transport and spatial changes have sprung up rapidly throughout England on a temporary and sometimes experimental basis. The majority of the schemes have been funded through the (Emergency) Active Travel Fund, which was designed to facilitate a rapid increase in walking and cycling whilst discouraging car travel.

Changes have tended to be introduced through experimental traffic orders, which means that all concerned obtain first-hand experience of the effects. Though these interventions have not been subject to traditional consultation processes, councils have still been engaging with their communities in various ways. In some cases, councils have been able respond to concerns or problems and have adapted the measures, possibly thereby building broader support for what has been done. But many councils have encountered significant and vehement opposition. People have expressed objections about the schemes themselves, the delivery process, or the methods of engagement used by their councils.

With the climate emergency and other major challenges in mind, the LGA commissioned the University of Westminster and Fern Consulting to investigate these events. We spoke with a range of councils and other stakeholders to identify the lessons that can be learnt. In particular, can the experience of promoting active travel during the pandemic help councils to engage more successfully with their communities in future when dealing with contentious issues?

Findings

Doing transport during a pandemic

As the pandemic struck, councils found themselves in an extremely challenging situation. Many were short-staffed due to the impact of COVID itself, or the need to care for family members; in some cases transport officers found themselves doing front-line work such as distributing meals. So it is important to start by recognising that the amount of transport work done was remarkable given the circumstances. Many councils mobilised very quickly and some delivered schemes at an astonishing pace compared with “business as usual”.

And we must also acknowledge that the early stages of the pandemic exerted considerable stress on the general population too. This partially explains the strength of opposition to transport schemes that was seen in many locations, which in some cases was likely to have been the most visible manifestation of wider concerns and fears amongst the public. But there was more to it than that, as we show.

Before the pandemic

How transport schemes were received during the pandemic was influenced to a great extent by the history of interaction between councils and their communities prior to it. We found that areas where officers and councillors had been generally visible and available experienced less of a reaction. A by-product of this “ambient engagement” was the accumulation of a body of evidence concerning the views of a variety of stakeholder groups. This helped officers to design schemes that catered effectively to a broad range of interests. And, whilst some stakeholders participating in our research tended to be quite critical of their councils, they were more sympathetic towards councils that they saw as open.

The response to interventions also reflected the extent to which councils had established a “mandate for action” prior to the pandemic. This is not as simple as whether the relevant adopted strategy document set out principles which individual schemes followed – often, the level of community awareness of such strategies is very low. It is instead a question of broader legitimacy: Cambridge, for example, could refer to the support for road closures that had emerged from its 2019 citizens’ assembly. In other locations, popular support for the strategic direction had been achieved through extensive engagement over many months or even years. But this is bound up with what that strategic direction was, as we will explore below.

And a third aspect is whether councils had already been developing schemes prior to the pandemic. This was double-edged: well advanced designs could be implemented quickly with confidence that they would work compared with schemes conceived rapidly during lock-down. But critics of the schemes tended to see this as implementation by stealth: “And we just all felt that they’d taken complete advantage of COVID, legislation to implement something that they’d wanted to do forever” (focus-group participant).

The (Emergency) Active Travel Fund and its impacts

When Grant Shapps announced the Emergency Active Travel Fund on 9 May 2020, councils will understandably have had mixed feelings. On the one hand, this was substantial funding being made available at very short notice for measures that had historically been hard to finance. For councils, such as London boroughs, facing significant gaps in their finances as a consequence of the loss of their normal funding via TfL, it was seen as a lifeline in order to protect schemes and avoid loss of expertise. On the other hand, the conditions imposed were extremely demanding. The original guidance (May 2020) said “measures should be taken as swiftly as possible, and in any event within weeks” to take advantage of the short-term opportunity to change travel habits.

The list of potential measures, ostensibly lengthy, actually contained relatively few interventions that could be delivered within weeks. For example, changes to junction designs and “whole-route approaches” simply are not amenable to delivery with the rapidity envisaged. It is therefore understandable that the bulk of interventions were cycle lanes, footway widening, low-traffic neighbourhoods (LTNs) and school streets. In the words of a former transport officer, “if you want to change the transport network, the only things that you can actually really do very quickly is to get rid of parking or shut roads”. Nevertheless, to their credit, councils did act quickly, as instructed.

They may have therefore been dismayed when, some months later, the Secretary of State wrote to local transport authority leaders, taking a much less bullish line about active travel and seemingly seeking to placate drivers. And, over the year since it was first released, the guidance has changed significantly: the reference to acting within weeks has gone and, in its place, “measures should be taken as swiftly as possible, but not at the expense of consulting local communities.”

That the guidance was changed is not surprising given the extent and vehemence of opposition to some of the measures that had been implemented. And the government could point out that it never removed any requirements for consultation inherent in the various forms of traffic regulation order. But this change in emphasis could be seen as a rebuke and councils might reasonably feel undermined: after all, they had done as they had been asked, and in very difficult circumstances.

The remainder of this chapter explores the variety of opposition experienced by councils: why has the backlash been so much fiercer in some places than others? And what can be learnt from the experience? Before proceeding, a note on terminology: the “Emergency” prefix has been dropped from the Active Travel Fund so we shall use the following abbreviation from now on: (E)ATF.

How councils performed

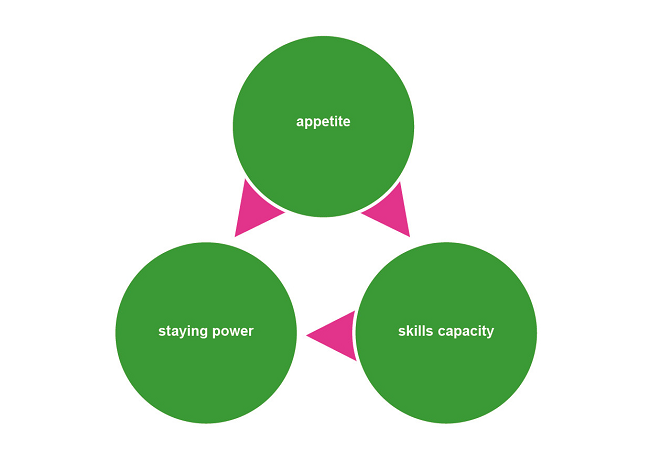

To illustrate our findings, we have developed a simple conceptualisation (see diagram 2):

Appetite: how much do relevant council figures want the outcomes which these interventions are predicted to bring?

Skills/capacity: does the council have (or can it obtain) the knowledge, skills and muscle ─ including with respect to engagement ─ to design, negotiate and deliver successful interventions?

Staying power: given that some opposition is inevitable, does the council have sufficient commitment to follow the process through?

The bulk of our findings are explained by the various ways in which these elements combined from council to council. We discuss the conceptualisation in more detail towards the end of this chapter.

We make more specific remarks below but start with a general assessment. The main point is that councils were working in exceptionally difficult conditions and that some lapses were inevitable. Some schemes were introduced with very little warning and the information provided in advance could be hard to understand for some members of the public approaching the subject fresh. We found that councils acknowledged this and that practice had improved during the pandemic. “Going forward, yes, in terms of that engagement, we would try to certainly do more upfront” (transport officer).

We found evidence of a variety of openness and responsiveness, with citizens referring both to officers being willing to meet to discuss design details and to being “left on hold for half an hour, and it rings and rings and rings” (focus-group participant). This recalls our earlier point about the prevailing relationship between councils and their communities before the pandemic. Some councils clearly took the decision to “dig in” and this was described as “straight out of the London Cycling Campaign handbook” (focus-group participant), a reference to a guide that encourages councils to “stay strong” (Rosehill Highways, Living Streets, and London Cycling Campaign, 2021). Elsewhere, officers and councillors attempted to respond quickly to questions and requests. “And I think…the flexibility of what we’ve done, has meant mistakes that have been made have been rectified very quickly, as quickly as the schemes have gone out and we’ve learnt to talk to people that would have never talked to you before…because we’ve put a traffic cone outside people’s houses” (councillor).

Much more could be said about councils’ performance in general but we pick out two specifics: first, the move to online meetings as a result of the pandemic has resulted in council business seeming more visible and more accessible – attracting potentially a wider range of participants than would turn up to a typical town hall style meeting of an evening. Those seeking to get schemes altered or removed have taken the opportunities to engage in council meetings and this has meant a widening of the constituency participating in local democracy. Whilst this is something to celebrate it has also exposed councils to closer scrutiny and criticism. Those opposed to a council’s action were quick to call out lapses of probity or competence as they saw them and councillors varied in the speed with which they adapted to being more exposed. On a more positive note, the increased scope for gathering was seen as beneficial: “[the online workshop] was for people to hear each other’s experiences and actually everybody was incredibly respectful, because a lot of people really benefited from the [scheme]” (transport officer).

Second, many of the complaints against schemes have been quite specific, relating to the experiences of individuals whose travel was affected. Much of the time, councils respond to such claims with generalities, referring to the aggregate benefit of the scheme. This is reasonable, particularly if there is no immediate “fix” for the individual’s worry. But it can also exacerbate ill-will, as the individual will understandably find little solace in knowing that the difficulty they are experiencing is outweighed by benefits enjoyed by others. It will also have little positive impact in places where those claims of aggregate benefit are themselves being disputed.

Major themes

The variety, origins and justifications of interventions

Having listed above the interventions most widely employed by councils, we note an apparent spatial disparity (not tested empirically): LTNs were implemented more in southern England, especially London, whereas cycle lanes were more widely employed by northern boroughs. And it perhaps goes without saying that perceptions of quality varied: some schemes appeared to work well whilst others were roundly criticised as having fundamental flaws. Many of the latter type were swiftly amended or removed. Perhaps the most interesting variety was seen in the rationales presented for action. Social distancing was routinely mentioned alongside a response to reduced capacity on public transport. But these COVID-based arguments were accompanied to differing extents by claims about the inherent desirability of active travel as well as the climate emergency, amongst other things. There is also some evidence of a vogue for LTNs: an intervention that was very new (at least under that name) went from obscurity to ubiquity in an extremely short time, without an especially strong case for it as a response to COVID. This may of course reflect the rather limited palette of interventions available to councils.

Critics were quick to point out what they saw as design weaknesses: why was a given road being filtered, for example, if there was no obvious rat-running problem on it? The idea of “traffic evaporation”, though an established fact in academic and professional circles for 30 years or more, is regarded with deep scepticism by much of the public. As a consequence there was an understandable concern amongst those on roads that were remaining open to through traffic that they were the “losers” from this policy and that was unjust. A perception (again not necessarily supported by evidence) that such communities who live on the busier roads in London were already suffering from poor air quality and higher general levels of economic deprivation also fed a narrative that the policy entrenched, rather than addressed, inequality. Weaponisation by some campaigners of other emotive issues such as emergency-service access times and impact on mobility-impaired people who relied on their cars, further fanned these flames. In each case these concerns could often be addressed through reference to relevant research findings but, as noted elsewhere, these necessarily refer to the aggregate impacts of such interventions, rather than the specific matter of an individual scheme which will always have local nuance. As a consequence councils found themselves fighting the same battles over and over again for each scheme given a lack of awareness of the wider rationale for such changes, and had insufficient time to communicate this effectively to the public.

Critics also raised concerns about an apparent select few stakeholders (particularly cycling groups) being granted an active role in the design process (something confirmed to us by activists) though, to the extent this happened, it is an understandable reaction to the staffing challenges councils were facing.

Telling a story

The (Emergency) Active Travel Fund was ring-fenced for transport interventions and most schemes it funded have been delivered through traffic regulation orders. Add to this the fact that regulations require certain signage to be used (eg “no through route except cycles”), and this has meant that the default narrative surrounding intervention was a transport one. As one citizen put it, “it really pitted drivers against everyone else, pedestrians and cyclists mostly, when there was very little thought put into what the benefits were beyond transportation” (focus-group participant). A perception that cycling is practised by elites has magnified this feeling of us and them.

Though transport is at the heart of these interventions, a much wider story can be told. Many authorities included road safety, physical activity, air quality and noise in their accounts, and some also mentioned climate change. But relatively few took the opportunity to characterise interventions more broadly, appealing to issues of equity, economic vitality, the quality of public spaces and quality of life more generally. Where councils were felt not to be grasping this opportunity, activists sometimes stepped in to present this narrative themselves. Many councils have a stated vision for their communities and there was an opportunity here to connect the particular interventions to that. There is no guarantee that this would have lessened opposition but it may have helped, particularly in terms of mobilising a larger set of stakeholders (public health, economic development etc) to argue in favour of action. “Don’t give ground unnecessarily because there’s a bigger prize to be won you know beyond the temporary scheme. Don’t give ground too easily and we’ve said that because these schemes are there for a reason. They are there to protect people’s health and are there to protect economies. And so, where you have individual complaints, very loud complaints, you have to test those against the reason for you doing the work in the first place” (councillor).

In contrast, there is evidence that some councils responded to opposition by revising the justifications offered for intervention over time. This both created uncertainty and strengthened the position of those arguing that schemes lacked a compelling case. Having said this, the ambiguity began with the funding from central government itself. It was released on an emergency footing, but the accompanying explanation was of grasping the opportunity given “the urgent need to change travel habits before the restart takes full effect” (Department for Transport, 2020). There is a clear misalignment here between the presumably temporary nature of the pandemic (and associated imperatives) and the aspiration to achieve lasting change (“habits”) in travel behaviour. This misalignment gave critics some justification for accusing government (central and local) of behaving opportunistically.

LTNs add complexity to this picture because, unlike footway widening or cycle lanes, the link between the pandemic and the intervention is not obvious. Social distancing did not tend to present difficulty on residential streets before they were filtered; and, whilst walking and cycling was made easier within the LTN itself, conditions remained the same, or indeed potentially worsened, in the (untreated) surrounding area and on those distributor roads that remained open to through traffic. In other words, LTNs may have succeeded in discouraging car use but may only do a partial job of encouraging more walking and cycling.

What do “the people” think?

The received wisdom is that those who strongly either support or oppose this wave of interventions represent a small proportion of the overall community. Use of social media is often credited with making views seem stronger and more widespread than they actually are. And some interest groups (notably cycle campaigns) are perceived as being well organised and well connected, thereby enjoying undue influence. If this characterisation is accurate, councils can reasonably ask what “the people” actually think. Perhaps there is a large group of people who have no particular opinion yet or who are quietly supportive. But, because propensity to voice an opinion is correlated with the strength of that opinion, these people’s views are not informing the debate. Councils, meanwhile, continue to struggle to capture the views of the seldom heard, including young people, people from black and minority-ethnic communities and homeless people.

Some communities where we maybe haven’t done as much work on active travel in the past, who to engage with and how to engage with those communities? There’s always a job of work to be done there. We don’t want to always be talking to the same people. So often you find it in council consultations, the responses come from the same people”

- Councillor

Some efforts have been made to obtain a representative picture of public opinion. There is limited value, though, in asking general questions about support for a given type of intervention, since the detail of a scheme (who is affected and in what way) is crucial to its reception. We are not aware of a representative survey that addresses satisfactorily the trade-offs inherent in these schemes. But the principle of doing this seems valid, precisely because the debate has become so polarised in some locations.

I think the challenge of transport is that all our debates are often quite polarised between people who are very cycling focused, people who want to be able to drive everywhere, and then disabled groups.

"And they are very polarised, those three groups, and what we’re missing is the bit in the middle, around people who maybe cover two or three of those things or are members of all those groups but don’t have strong opinions on it” (transport officer).

Obtaining a representative picture of opinion does not remove the need to have appropriate regard to submissions made as part of consultations, whether they are formally promoted – “tell us your views” – or take place automatically, as in the six months following the launch of an experimental traffic regulation order. And, if the representative view were quite different from that arising from self-selecting contributors, the council would face a dilemma. This arose in Croydon, where the local MP accused the council of being disingenuous in its interpretation of consultation responses. In deciding a way forward, councils should take into account strength of feeling (does strong opposition have more weight than mild support?) as well as extent of impact – the views of someone whose essential travel now takes 40 minutes longer per day may be considered differently from those of someone who is only marginally or indeed not at all personally affected.

The use of trials

A great deal of the controversy associated with work funded by the (E)ATF arises from the use of trials, typically under an experimental traffic order. First and foremost, this is unfamiliar: people who were used to consultation prior to any decision being taken were shocked when works commenced on their doorsteps, sometimes with very little warning. We have been conditioned by standard consultation to think that nothing significant will be done before the views of the community have been carefully considered by the council. Even those who trusted their council may have wondered whether what was being done was truly an experiment. Meanwhile, those who were suspicious of their council tended to think that the trial was a convenient way of getting some pet scheme implemented, with a strong presumption that it would remain.

There are strong, practical reasons for trialling interventions before deciding whether to remove, alter or retain them. “An experimental scheme, everybody knows it’s there because they can see it and then they have the opportunity to give their view on whether they like it or not. So I think there’s quite a good argument of, leaving aside COVID, experimental schemes, and we’ve seen them work elsewhere....for sure when you first put the scheme in with limited pre-engagement, there is some disbenefits, but there are also advantages to trialling schemes in terms of meaningful engagement as well” (transport officer). But the unfamiliarity of the process meant that councils faced an uphill struggle convincing their communities. We were told that it helped to be told the exact criteria that would be used to judge whether a scheme had been “a success”. But critics complained that councils had been very unclear about the process and timescale, particularly the role formal consultation would play. There were also concerns raised by some that councils were only paying lip service to the idea that these genuinely were trials, and some saw this as evidence that they were “digging in”.

For their part, officers saw the need for more advance warning in future and several councils were inclined to return to carrying out consultation before implementation using an experimental order, even though it is not required.

I think working with the community during the trial is a good approach to take. And allowing them to be involved in designing the scheme”

- Transport officer

It is important to recognise that such consultation prior to trial commencement does not necessarily need to take the form of a “referendum” – a more collegiate approach to co-designing potential trials with the community could be adopted, noting though the time and staff resource such methods entail.

Emergencies

The pandemic has provided ample evidence about our readiness to accept significant restrictions on our day-to-day behaviour and habits in the context of an emergency. People stayed away from public transport and wore face coverings if they had to use it. Though compliance may have declined over time, the immediacy and severity of the threat of COVID seem to have persuaded most people to follow instructions.

The character of the risk helps to explain the range of reactions to schemes funded under the (E)ATF. Footway widenings were broadly welcomed or at least accepted, probably because they were visibly temporary – the plastic barriers tended not to last – and because their relevance to enabling social distancing was obvious. The COVID argument for pop-up cycle lanes was slightly less direct and there was more scrutiny of whether they were being used sufficiently to justify their retention. And, as mentioned above, LTNs were perhaps the hardest to justify in terms of COVID - which helps to explain why focus-group participants used words such as “opportunism” where these were concerned. In summary, the misalignment between motive and response that underlay original government guidance on the (E)ATF was translated into a perceived misalignment at the council level. This was recognised by case-study interviewees: “[a lesson] may be to think quite hard about opportunistic schemes and whether they are the best things to do” (transport officer).

The other significant finding with respect to emergencies relates to climate. A case can be made that the climate emergency is at least as serious and pressing as the pandemic, but this is not reflected in the popular consciousness.

We need to deal with not only the pandemic but start dealing with issues like the climate crisis, but that’s not as evident and is not in front of us. And there’s more time and I guess less fear, less immediacy, and less motivation bureaucratically around that”

- Transport officer

People therefore objected to the use of climate change to justify schemes for two reasons: first, because action had been presented as necessary as a result of the pandemic, not climate change and, second, because they perceived it to pose a much lesser threat to them.

Ways of thinking about the issues

We offer the following conceptualisations to help to illustrate the phenomena that we have discussed in this chapter.

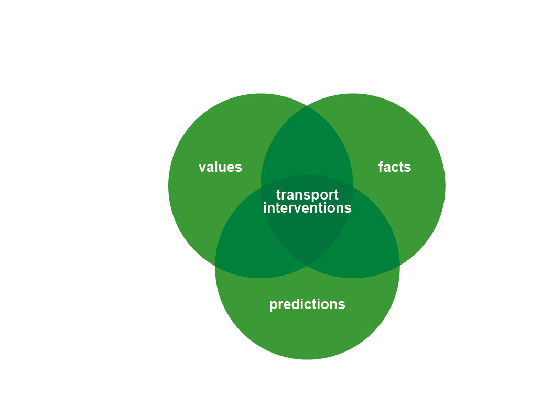

Values/facts/predictions

Diagram 1

Most transport interventions lie at the intersection of this diagram: if an intervention is justified, this is because a) it aligns with our values, and it is supported b) by relevant facts about current conditions, and c) by predictions concerning the future, in particular what will happen if the intervention is implemented. Put crudely, the more harmony amongst stakeholders concerning these three elements, the more acceptable the intervention. Our investigation has shown divergence in all three. First, there is a lack of unanimity about what is desirable (values): those providing or using the funding were committed to fostering active travel whilst (implicitly or explicitly) seeking to deter private motorised transport. This commitment was plainly not universally shared. Second, there is disagreement on the relevant facts as they relate to levels of traffic, road danger, demand for various modes etc. And, third, predictions (of distribution of impacts, uptake, displacement, congestion and so on) have also been extensively disputed. We have argued that the root cause of these divergences is dissonance within the original conception of the (E)ATF. This is in part an issue of fact – the disputed proposition that the schemes supported by the Fund would provide protection against COVID-19. It is also a matter of values, given the lack of popular consensus concerning the case for active travel, with or without a pandemic.

We claim that, of the three, divergences of values have had much the greatest impact. But we note that, when values do not align, this is more often than not expressed in arguments over the facts or the validity of predictions. The various legal disputes taking place at the time of writing have the appearance of being about facts or predictions – whether a given council followed the correct procedure or estimated an impact accurately. But the reason they are happening is the divergence of values. Further, whilst a difference of values can be manifested in an argument about facts or predictions, it does not follow that facts can be used to resolve a difference of values. More specifically, telling someone that their car use is contributing to climate change will not typically lead them to lose their enthusiasm for driving. Councils wishing to inculcate sustainable mobility in their communities will have more success if they engage on values but they will need to be in it for the long haul.

Appetite – skills/capacity – staying power

Diagram 2

This simple structure represents three essential and connected components of successful implementations.

Appetite: how much do relevant council figures want the outcomes which these interventions are predicted to bring?

Skills/capacity: does the council have (or can it obtain) the knowledge, skills and staff numbers ─ including with respect to engagement ─ to design, negotiate and deliver successful interventions?

Staying power: given that some opposition is inevitable, does the council have sufficient commitment to follow the process through?

The first component, appetite, helps to explain the wide variety of action amongst councils: some chose to do a great deal whilst others did very little. It is helpful to explore the source of that appetite, by distinguishing between intrinsic motivation (councils having a prior commitment to active travel) and extrinsic motivation (the stimulus provided by the funding). Intrinsically motivated councils were likelier to marshal (or already to have) the necessary skills/capacity for the task. This increased the chances of a successful outcome in the long run, because good design and engagement reduced the probable intensity of any opposition. Extrinsically motivated councils may have been less well prepared which helps to explain why some withdrew schemes very soon after implementation. Staying power is a function of many elements. It is positively correlated with appetite: the larger the number of enthusiasts in the council and the greater their enthusiasm, the likelier it was that the council would weather the storm.

Enthusiastic councils were also likelier to have established a supportive vision to which they could appeal when faced with opposition. Staying power is also a function of the quality of schemes and the way they were presented to the community, themselves both products of having the right skills and capacity – stronger and better understood schemes met with less resistance. It is partly determined by the prevailing relationship between the council and its community: where “civic infrastructure” existed, councils experienced less opposition, that is, the storm was less severe and therefore easier to withstand. Finally, it is related to the political environment: the more the promotion of active travel was a matter of consensus within the council and amongst influential stakeholders, the more likely it was that the enthusiasts could weather the storm.

Lessons learnt

In this chapter, we present the lessons that arise from our research.

It pays to invest in doing engagement well

Engagement is a skilled activity and doing it well requires considerable resource (time and staffing) – where the intervention itself is low-cost, engagement may in fact legitimately consume the largest proportion of the budget. It will be most successful when carried out by staff with appropriate training and experience, working alongside transport professionals who specialise in design, feasibility etc.

Whilst it is essential to carry out targeted engagement as part of developing any scheme or strategy, many councils have benefited from taking a more continuous approach to it, building the “civic infrastructure” that establishes trust with communities and effective lines of communication.

The pandemic has forced much engagement on-line and this has had positive and negative impacts. Understanding is growing concerning what does and does not work well with on-line engagement and councils can profit from staying abreast of this.

With active-travel schemes particularly in mind, councils can smooth the path by providing clear, evidence-based and consistent explanations for design details (eg why this road and not that one?) It is, though, necessary to accept that some level of opposition to change is inevitable, however well engagement is done. Time spent in advance, preparing in detail how best to respond to this (eg staffing arrangements to support answering a surge in FOI requests, petitions, general complaint procedures etc) would be prudent and likely to help support the smoother delivery of change in the longer run through reducing second-order complaints about poor administration and slow response times etc.

The whole community has valuable expertise to contribute

It is quite understandable that councils will liaise with groups whose interests align with the goals of a given initiative. It is also the case that groups and individuals who are not natural supporters of that initiative will have useful insights to offer. A visibly open approach to seeking views from a wide range of stakeholders at an early stage is likely to result in a better design and will reduce the risk that distrust arises as a consequence of a perception that the council has been “captured” by any particular special interest group.

Representative and/or considered views can be very valuable

Where debate has become or threatens to become polarised, councils can benefit from seeking the opinions of a socio-demographically representative sample of the community. It can also be useful to organise a deliberative process to understand how stakeholders feel when they have considered relevant evidence and arguments in a structured way. Referring to the lesson about engagement above, councils should see the resources required as an investment rather than a cost. In both cases, it is essential that any process addresses the true points of disagreement. In the case of this research, the central trade-off is between facilitating active travel and inconveniencing those who drive ─ any process would have to tackle this directly. Where feelings are strongly held, there is a case for asking an independent provider to lead the process.

Useful as the outputs of such exercises can be, they do not replace the results of consultation. Where it is expected that the two may differ significantly, councils need a fair and clear approach to managing that difference when working towards decisions.

Principles first, then details

There are considerable benefits for councils in establishing a mandate for action based on agreed principles before applying those principles to the development of specific interventions. Whilst that mandate is unlikely to be a consensus as such, it needs to have arisen following an open and inclusive debate that has been promoted to all members of the community affected. It must also be shown to enjoy some level of popular support. Reflecting the argument about the relationship between values, facts and predictions, the development of principles relies on a dialogue with communities about their values: “what do you like about your area?”; “what needs to change?”

Once those principles are in place, councils can appeal to them when presenting specific proposals but should not need to be drawn into renegotiating them. Engagement on the proposals can then concentrate on their details rather than a debate about those underlying principles.

Narratives matter

Though they are transport schemes, the measures funded by the (E)ATF can be characterised much more broadly, with reference to equity, public health, environment, local economies and quality of life/welfare more generally. This enables a wider range of voices to be mobilised in support of the interventions and can avoid an adversarial “us and them” framing of the issues. Where the council has an established vision, the links between it and the interventions can be drawn to good effect.

A strong and broad narrative, supported by sound evidence and valid wider research, provides the council with a basis for articulating the benefits to its community. And, when councils are in dialogue with people opposed to the interventions, it offers them a range of possibly compelling arguments.

Trials have a great deal to offer, when done properly

The key selling point of trials is that they allow decisions to be made on the basis of experience rather than speculation. In addition, by happening on the doorstep, they tend to engage many more people and a more diverse group than traditional consultation would. When carried out under an experimental traffic regulation order, they offer more freedom to make adjustments than under a standard traffic regulation order. But trials remain unfamiliar and people can be sceptical about the true intentions of councils that use them.

A proper trial process starts by giving communities thorough and clear information about the process ─ and the more warning, the better. It is crucial that the information provided leaves no room for doubt about how and when engagement and consultation will take place. Councils can increase the chances of a harmonious experience for all by setting out in advance of the trial the grounds for a decision to remove, alter or retain the intervention. They must support this with a programme of thorough monitoring that will enable that decision to be made on sound evidence.

Some councils choose to hold a dialogue with communities in advance to help define an intervention and this is very likely to help keep relations cordial. But it is more important that the council shows commitment to the spirit of trialling an intervention; any communication that implies a decision has already been taken is very likely to be damaging.

Councils can help themselves and their communities by implementing inexpensively and flexibly, thereby allowing changes to be made quickly and affordably. And an essential aspect of the spirit of trialling is readiness to admit when something is not working as intended, and changing it.

An accessible and responsive council will earn trust

Scheme opponents who spoke to us singled out the difficulty they experienced in making contact with and obtaining information from the council. They understandably thought this experience was a result of their views. And, whatever the facts of any case, it is natural to behave defensively when faced with criticism. But officers and councillors who are able to treat stakeholders even-handedly, regardless of their stance, will be building confidence in the council for the future.

More specific to the (E)ATF interventions, many of the complaints raised have been particular, relating to the impacts experienced by individual householders. We detected a tendency to respond to these with general statements about schemes’ aggregate benefits. Valid as such statements may be, councils should recognise how frustrating they will seem to people who are worried about how they will now get to their hospital appointment. Where possible, particular concerns should be met with particular responses, even if this is simply a matter of recognising the inconvenience that a scheme can impose. Part of the process of building trust will necessarily require an acceptance that there are trade-offs from many of these changes. And, for all the wider benefits they may bring, there may be some genuine losers. Their concerns and feelings need to carefully acknowledged, even if no mitigation is possible.

Transparency remains the best policy

As we have discussed, councils often found themselves in an impossible position, being obliged by government guidance to take forward wide-reaching changes to the established highway network on the basis that the pandemic required this, a contention that was poorly understood or outright refuted by many of those affected. The outcome of progressing schemes with this framing was often the perception that the pandemic was being used opportunistically by councils ─ this created strong resentment amongst those who objected to these interventions being brought forward. Whilst the emergency made communities somewhat more accepting of rapid action, it did not excuse councils from having to construct and communicate sound arguments to justify schemes. This task was undeniably made much more difficult by the clear framing by central government in their statutory guidance of the need for urgent action as being linked to the pandemic, when the rationale for many interventions was clearly more closely linked to the climate emergency.

There is a connected point about consistency: councils were criticised for appearing to revise the rationale for schemes when the original rationale was challenged. The theme also extends to process: for example, needless frustration can be avoided by making clear how comments or submissions from the community will be used at a given stage in proceedings.

Good schemes take time

The (E)ATF process imposed a punishing timetable on councils that were already under extreme pressure. This helps to explain many of the problems that have arisen in the last year with respect to delivery. Pandemic emergency or not, rushed designs will be weaker and may ultimately fail in time if they do not secure broad public support. Whilst there is no doubt that the climate emergency is severe and pressing, the clear evidence from the last year is that short-cuts in design or engagement are unlikely to save time in the long run. They may actually serve to increase barriers to change over time if opposition becomes entrenched. In summary: measure twice, cut once.

Research method

The method used in this research has been designed to help us understand these street transformation processes. We have used a variety of qualitative research methods to explore the range of perspectives and experiences towards the different schemes that we have looked at.

We selected four case studies across England to ensure we had a fair geographical representation and a wider perspective on the issues we are looking at.

Cambridge is often described as England’s “cycling capital”. In 2019, it held a citizens’ assembly on transport and amongst the recommendations was the closure of roads to motorised traffic. With respect to transport governance, the Cambridgeshire & Peterborough Combined Authority is the transport authority, Cambridgeshire County Council is the highway authority and Greater Cambridge Partnership is delivering transport schemes under delegation from the County.

Lambeth is a borough in inner London and so receives its transport funding through Transport for London. It was amongst the first English authorities to implement low-traffic neighbourhoods in the wake of the pandemic. According to its transport strategy, almost four out of five trips made by Lambeth residents are by public transport, walking and cycling.

Leicester is a unitary authority surrounded by the two-tier county of Leicestershire. It has a long history of promoting cycling and was noted last year for the speed with which it rolled out 11 miles of pop-up cycle lanes aimed at essential commuters, especially health and care workers on low incomes.

York is also a unitary authority and has a strong track record of transport demand management. In addition to being well known for its park-and-ride network, York has one of the largest pedestrian zones in Europe, called Footstreets. Vehicle access to the Footstreets network was further reduced during the pandemic to facilitate social distancing and to enable businesses to expand out in to the highway.

In each of our case studies one transport planner and one councillor were invited to separate online interviews. Interviews consisted of 10 to 12 questions that allowed an in-depth exploration of each of our four cases. In total we conducted seven online interviews. The interviews with transport planners and councillors provided insights into the challenges faced by councils in terms of resources, delivery and implementation of schemes and engagement with communities.

To complement the specificity of the case studies, we also conducted two online focus groups, one with supporters and one with those who opposed these interventions. The aim was to explore their views on their councils’ engagement approaches to understand more fully their perspectives on the implementation and delivery of the active travel schemes and their concerns. In both focus groups we explored the relationship between scheme attributes, engagement approach and stakeholder reaction.

Lastly, we organised an online symposium with selected experts from practice and academia, deliberately combining transport expertise with insights into democratic methods. We used the symposium to validate and test the themes and findings that had emerged from the interviews and focus groups.