Introduction

This Local Government Association (LGA) workbook has been designed as a distance learning aid for local councillors. It is intended to provide councillors with insight and assistance and develop key understanding and skills which will help you be most effective in your role. Some of the content may be most of use to more newly elected councillors, but nonetheless the subject we are dealing with is a challenging one and so it should be of use to more experienced councillors as well by way of a refresher.

The workbook considers the way local councils receive their funding and highlights both the legal and best practice requirements in managing the council’s financial affairs. If you serve in the scrutiny function, you may also like to use the LGA’s ‘Councillor’s workbook on scrutiny of finance’, which builds upon and complements this workbook.

The workbook can be used as a standalone learning tool, but, along the way, the various sections suggest that you obtain and review key financial documents from your council. All of these documents are publically available and so will be easily downloadable from your council’s website.

You do not need to complete it all in one session and you may prefer to work at your own pace. However, it is suggested that you complete the sections in the order in which they are written, as the latter sections build upon the knowledge you have gained in previous sections. It is also hoped that you can ‘dip in’ to any section for a refresher at any time in the future as well.

A list of useful additional information and support is also set out in the Appendix to the workbook.

You will note that some terminology used in this workbook is in bold type. This means that the term is more fully defined in the glossary of terms at the end of the workbook.

Throughout this workbook you will encounter different types of information, and suggested actions, indicated by the symbols shown below:

Guidance

– this icon indicates guidance such as definitions, quotations and research

Challenges

– this icon indicates questions asking you to reflect on your role or approach

Case studies

– this icon indicates examples of approaches used in different settings

Hints and tips

– this icon indicates best practice advice

Useful links

– this icon indicates sources of additional information

The context

The importance of local government finance

Every council requires money to finance the resources it needs to provide local public services. Therefore, every councillor should take an interest in the way their council is funded and the financial decisions that the council takes.

Legislation is clear that every councillor is responsible for the financial control and decision making at their council. The Local Government Act 1972 (Sec 151) states that “every local authority shall make arrangements for the proper administration of their financial affairs…” and the Local Government Act 2000 requires Full Council to approve the council’s budget and council tax demand. However, it is recognised that councillors may well not be financial experts and so legislation also requires that every council has a named ‘Responsible Financial Officer’.

The responsible financial officer

Whilst section 151 of the Local Government Act 1972 makes clear that the council is responsible for the overall financial administration of the council, a key way in discharging this function is the requirement that councils “secure that one of their officers has responsibility for the administration of those affairs”. Section 113 of the Local Government Finance Act goes further and requires that this officer is a qualified member of one of the accountancy institutes (such as, but not exclusively, The Chartered Institute of Public Finance and Accountancy, CIPFA). Therefore, every council designates a

specific officer as their responsible financial officer, also known as the council’s ‘Section 151 officer’. This person is usually the head of the council’s finance function and is central in providing:

- effective financial advice to councillors and officers

- organising and maintaining a sound system of financial governance and control

- ensuring that the council follows all of its legal duties in financial matters.

Preparing and approving a budget

A sound budget is essential to ensure effective financial control in any organisation and the preparation of the annual budget is a key activity

at every council. Budgets and financial plans will be considered more fully later in the workbook, but the central financial issue at most councils is

that there are limits and constraints on most of the sources of funding open to local councils. This makes finance the key constraint on the council’s ability to provide more and better services.

Every council must have a balanced and robust budget for the forthcoming financial year and also a ‘medium term financial strategy (MTFS)’ which is also known as a Medium Term Financial Plan (MTFP). This projects forward likely income and expenditure over at least three years. The MTFS ought to be consistent with the council’s work plans and strategies, particularly the corporate plan. Due to income constraints and the pressure on service expenditure through increased demand and inflation, many councils find that their MTFS estimates that projected expenditure will be higher than projected income. This is known as a budget gap.

Whilst such budget gaps are common in years two-three of the MTFS, the requirement to approve a balanced and robust budget for the immediate forthcoming year means that efforts need to be made to ensure that any such budget gap is closed. This is achieved by making attempts to reduce expenditure and/or increase income. Clearly councillors will be concerned with any potential effect that these financial decisions have on service delivery.

Current developments in local government finance

The detailed finance rules and regulations for local councils are complex and ever-changing. However, over the past few years, there has been a significant change in the overall approach to local government funding. These key changes are outlined below.

Prior to 2010 – councils operated in a highly centralised national funding system. As such, a large percentage of the council overall funding was determined by central government through a complex central grant system. This grant system attempted to model a council’s spending need through a set of formulae designed to determine the relative need of one council when compared with others. Grant funding was then provided to councils on the basis of their relative need.

This centralised system had advantages and disadvantages: the key advantage was the attempt to move money around the country to ensure that councils who were less able to raise income locally received the funding they required to maintain essential public services. The main disadvantage was that, as a result, there was limited financial incentive for councils to develop and grow their local economy, as the consequent financial benefit did not always stay locally.

Since 2010 – Government has sought to make the local government funding system more locally based, phasing out general government grant altogether. Whilst there still is a formula approach to distributing money around the country on the basis of need, more additional funding is being retained locally. For example, from increases in rates collected from new businesses. The process of localisation is set to continue over the next few years.

One of the key implications of this change in government policy is that local decisions affecting the local economy now have important implications on council income. Therefore, the policy objectives and decision making of the local council plays a far more significant role in the council’s ability to raise income than before.

The councillor’s role

Value for money

What is the councillor’s role in all of this? Put simply, it is to consider the council’s finance and funding as a central part of all decision making and to ensure that the council provides value for money, or best value, in all of its services.

There is unlikely to be sufficient money to do everything the council would wish to provide due to its budget gap. Therefore, councillors need to consider their priorities and objectives and ensure that these drive the budget process. In addition, it is essential that councils consider how efficient it is in providing services and obtaining the appropriate service outcome for all its services.

Hints and tips

An important aspect of considering value for money is to make comparisons with other councils. The LGA provides an online tool where council performance can be compared with others. This can be accessed at http://vfm.lginform.local.gov.uk/

Challenge 1

Find out who the Section 151 officer is at your council. Consider how s/he fulfils their statutory responsibilities in terms of securing effective financial administration and control.

Obtain a copy of your council’s MTFS and look to see if there is a ‘budget gap’. How has your council closed such budget gaps in past years? How are councillors involved in this process?

How can councillors monitor whether the council provides best value?

Take a look at the LGA’s performance tool – how is your council doing when compared with others?

Key concepts

The difference between ‘revenue’ and ‘capital’ finance

Local councils, together with all public bodies, receive separate funding for their revenue and capital spending and their financial systems must be able to separate the income and expenditure on revenue activities from the income and expenditure on capital activities. The distinction between revenue and capital spending is much stronger in terms of the sources of council finance than you might ordinarily expect to find in say the accounts of a business or other organisation.

Revenue – this is the council’s day-to-day expenditure and includes salaries and wages, running costs such as fuel, utility bills and service contract payments. As a rule of thumb, if the expenditure is consumed in less than a year, then it is revenue. The council funds revenue expenditure through revenue income sources such as the council tax and charging users for the services they use.

Capital – if the council spends money on improving the council’s assets, then this is capital expenditure. This would include purchasing new assets, such as land and buildings, but also refurbishing and improving existing ones. Capital expenditure is funded through capital income sources such as capital receipts and borrowing.

Councils need to ensure, and also demonstrate, that they are complying with these rules by making sure that there is a clear separation between capital and revenue in all of its financial activities.

Grey areas

Usually, it is clear whether a transaction is revenue or capital, but there are some grey areas. These include:

- Maintenance and repairs v refurbishment. The key concept here is that if the expenditure does NOT make the asset last longer, increase the sale value of the asset or make it more useful to the user, it is revenue expenditure. For example, repainting windows would be revenue expenditure whereas replacing the frame with UPVC would be capital expenditure.

- Staff costs such as architects. Staff costs are almost always revenue expenditure, but where the staff cost is directly related to a capital project, such as an architect or quantity surveyor, these costs can be added to the capital expenditure on the project. Note that this is sometimes very tricky and so your Section 151 officer will need to provide clear advice here.

- Income: any regular income derived from a capital asset, for example rent or service charges is revenue income. The proceeds of sale of an asset is capital income. For example, car parking income is revenue, whereas selling the actual car park site would yield capital income (known as a capital receipt).

As a general rule, councils are not allowed to use capital income to fund revenue expenditure (though they can use revenue income for capital expenditure). For example, a council could fund the purchase of land using revenue income such as council tax, but it would be illegal to sell land and use the sale proceeds to fund an officer’s salary.

Recently, the distinction between revenue and capital has been muddied somewhat by the Government allowing councils to use capital income to fund ‘the revenue costs of transformation projects’.

Guidance has been given to Section 151 officers on what can be counted as a transformation project, but broadly speaking, if the project is likely to save revenue costs in future years then any up-front costs (eg redundancy costs) can be funded from capital income if the council chooses to do so.

There may be other areas where there could be a ‘blurring’ between capital and revenue expenditure. For example with office equipment. As such equipment is likely to last for more than one year, equipment purchases could be capital expenditure, but the sheer volume of such purchases would make the accounting system unwieldy if every item was classified as capital. Therefore, most councils operate a local de-minimis level where equipment purchases below a cut-off amount are treated as a consumable item as so charged to the revenue budget. The cut off amount is subject to local agreement, but a de-minimis level of £5-10,000 for a district council and £25-30,000 for a county or unitary council would be typical.

Capital and revenue are different but linked

Whilst they must be accounted for separately, there are clear practical links between revenue and capital income and expenditure. For example:

- building a new leisure centre (capital expenditure) will also lead to staff and running costs (revenue expenditure) but also income through user charges (revenue income).

- investing in energy efficient boilers etc. (capital expenditure) may lead to ongoing savings on utility bills (revenue expenditure)

- purchasing an office block (capital expenditure) in order to provide office space for local business start-ups will yield rental income (revenue expenditure).

Therefore, councillors should concentrate on the ‘whole-life’ costs and income when considering budgets and financial plans.

‘Ring-fenced’ funding

Every council has a general fund from which most services are funded. However, there are restrictions where the council must ensure that certain income is only spent in specific service areas. This is known as ‘ring-fenced’ funding. There are three main activities that are ringfenced through legislation and/or government funding rules. These are:

The Housing Revenue Account

The Local Government Finance and Housing Act 1989 requires councils who own housing that they rent out to tenants to separate all of the financial activities relating to the council acting as landlord into a ring-fenced account known as the Housing Revenue Account (the HRA). Due to the ring-fence, it is illegal for the council to subsidise any general fund activity from its HRA and vice versa.

The ring-fence causes a practical issue, however, as the council’s housing department is likely to provide a wide range of housing related services that cannot be charged to the HRA (eg services for the homeless). To comply with legislation, careful estimates of the amount of money spent on general fund housing services and HRA services must be made, with the actual sums allocated to the correct account in the council’s financial ledgers.

School budgets

The Education Act 1988 established a system of individual school budgets, with local accountability for such expenditure resting on school governing bodies. Whilst many councils provide wider services for children and young people, the ring-fence around schools’ expenditure requires that the council must ensure that funding specifically provided for schools is spent only on this service area.

Academy and free schools are funded directly from central government and so do not form part of the council’s finances. Though, councils may provide services to such schools, such as payroll and other HR services through an agreed service contract.

Public health

Since 2013, local councils have received a government grant that must be spent on providing a range of public health services, such as interventions to tackle teenage pregnancy, child obesity, sexually transmitted infections and substance misuse. The specific government grant is must be spent on the service areas specified in the ‘grant rules’ and, as such, is ring-fenced funding.

The adult social care precept

For 2016/17, Government allowed local councils with responsibility for providing adult social care (ie metropolitan, unitary and county councils) to add an additional ring-fenced precept onto the council tax. Initially this was set at two per cent but was increased the following year to make the annual increase up to three per cent in any given year, but no more than six per cent over the three years 2017/18 to 2019/20. Any such precept must be separately identified on the council tax bill sent to residents.

Other locally ‘ring-fenced’ budgets

Whilst the term ‘ring-fenced’ comes from legislation, some councils also use the term more widely to restrict certain funding to a local agreed service area. For example, a council could agree to allow a council-run arts centre to reinvest the income it generates from fee-paying arts activities in the centre’s future. Thus, it has ‘ring-fenced’ this income to be used in a particular area. This is not a legal requirement but, where used, will form part of the council’s agreed local budgets etc.

Hints and tips

Councils sometimes have their own internal jargon and you may also find ring-fenced finance described as ‘earmarked’, ‘specific’ or ‘restricted’.

Activity 2

Which of the following transactions are revenue and which are capital? The answers can be found at the end of the workbook.

-

Filling in a small pot-hole in a council car park? Revenue/capital

-

Re-surfacing the entire car park?

Revenue/capital -

The annual cost of the council’s refuse collection contractor, who operates the service under a seven-year contract?

Revenue/capital -

Adding webcasting equipment to the council chamber costing £50,000?

Revenue/capital -

Redundancy costs of officers as part of a re-structuring programme?

Revenue/capital

Hints and tips

When you are reviewing any service plan, think whether the costs and income related to the scheme are capital or revenue, as the council will budget differently for these two types of expenditure.

Financial planning and budgeting

This section considers how a local council plans its finance and agrees its annual budget.

There is a significant amount of legislation around local authority financial planning and budgeting. This is outlined below.

- The Local Government Act 2000 states that it is the responsibility of the full council, on the recommendation of the executive (or the elected mayor) to approve the budget and related council tax demand.

- The Local Government Act 2003, section 25 requires the council’s Section 151 officer to report to the council on the robustness of the estimates made and the adequacy of the proposed financial reserves assumed in the budget calculations.

- The Local Government Finance Act 1988, section 114 requires the Section 151 officer to report to all of the authority’s councillors if there is or is likely to be unlawful expenditure or an unbalanced budget. The council must meet within 21 days to consider the report and during that period the authority is prohibited from entering into new arrangements that will cause money to be spent.

- Failure to set a legal budget may lead to intervention from the Secretary of State under section 15 of the Local Government Act 1999.

Notwithstanding the legislative requirement to set a budget, financial plans are important because they act as a financial expression of the council’s policies and instruct officers on the areas they should attribute spend.

The budget setting process

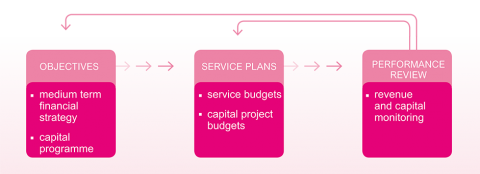

The three stages in the above chart are discussed further below.

However, finance should not be the driver at the council and it is important that all financial decision-making is policy-driven.

Stage one: medium term financial planning

Every council will have a Medium Term Financial Strategy covering estimated revenue income and expenditure over at least three forward years. It will also have a similar plan for likely capital income and expenditure, known as the Capital Programme. These are important financial documents and are updated and approved annual by elected members.

Stage two: annual service budgets, capital project budgets

The budget for the forthcoming year (year one of the MTFS) will then be considered in more detail, leading to the setting and approval of detailed income and expenditure budgets on a service-by-service basis. The capital budget for the year will be made up of budgets for the capital projects scheduled for the forthcoming year. Again, it is essential that the budget is set in accordance with the service plans and objectives for the forthcoming year.

Stage three: monitoring spending against the budget

Once the year has started, actual spending and income will be monitored against the approved budget. This is primarily undertaken monthly by officers designated as the budget holder (usually the head of service), with elected members receiving reports highlighting specific issues or concerns on a regular, usually quarterly, basis.

Timetables and deadlines

The Local Government Act 1992 requires the councils that billing authorities complete and approve their budgets and set a council tax before 11 March immediately prior to the start of the financial year on 1 April. The deadline for precepting authorities is 1 March.

The budget and council tax must be approved by full council prior to the start of the new financial year (1 April). However, this is the end of a very detailed budget setting process that progresses throughout the year at the council.

Whilst every council is slightly different, the illustration below gives a rough timetable of how the council reviews and approves its budget:

| Period | Stage |

|---|---|

| April - July |

|

| July - September |

|

| September - December |

|

| December - February |

|

| March |

|

The roles and responsibilities of councillors

Every councillor has a role to play in the budget setting process. Those serving on the executive have a responsibility to consider their service

portfolio in the light of its budget position. Councillors serving on overview and scrutiny also have an important role in regularly reviewing the council’s finances and in considering the proposed annual budget. In addition, every councillor will be concerned to ensure that services are delivered effectively in their local ward.

Most councils have formal processes to consult on its budget with residents, local businesses, partner organisations and service users, with the results taken into account when setting the budget.

Hints and tips

When councillors review actual spending and income against the approved budget, it is easy to focus on over-spending as it is ‘bad news’ and overlook under-spending as it is ‘good news’. However, always try to understand such variations in spending by considering why and how these have occurred.

For example, an over-spend might have occurred due to an exceptional demand for a statutory service (still bad news in the sense that money needs to be found to cover the amount, but maybe now more understandable). An under-spend may simply be due to the council not delivering the service for which the money was intended to be spent. Is this always good news?

Challenge 3

Obtain your council’s latest MTFS capital programme and annual budget report and consider:

-

What are the key messages?

-

How clear is the link between the council’s agreed objectives and plans and the budgets set?

-

What assumptions have been made in estimating future spending and income?

-

How has the budget taken the results of public consultation into account?

-

How can you as a councillor become more involved in the budget setting process?

Case study – effective budget consultation

The London Borough of Redbridge and the LGA has developed an online simulator that encourages members of the public to consider where council budget cuts should fall, where efficiencies might be made and where income might be generated. It starts with the premise that the available budget is overspent and identifies the council tax adjustment that would notionally be required to meet all demands in the budget. The council enters into the simulator the various detailed elements of the budget and other information such as the maximum council tax increase that would be acceptable. Users can then adjust elements of spending and income to balance the budget.

The sources of revenue funding

This section will consider in more detail the key sources of funding available to a local council to fund its revenue expenditure. Every source of income will have constraints stopping the council simply increasing the amount of income to fund services. Many of these are legislative constraints, but also council income sources can be subject the law of demand – as the price rises, demand tends to fall. Consequently, a price rise can yield less overall income if it results in a drop-in service use.

The Housing Revenue Account

The main sources of income in the Housing Revenue Account is housing rents, which is subject to overall government control. Councils will also levy service charges on tenants, for example on the cost of shared hearing systems. Such service charges are determined on a cost-recovery basis.

The general fund

The following sections consider the main sources of revenue income in the general fund.

Council tax

Council tax was introduced in 1993 by the Local Government Finance Act 1992 and replaced the Community Charge (also known as the ‘Poll Tax’). The tax is based on the value of domestic properties, in eight valuation bands. Various discounts are required by law, for example there is a 25 per cent discount for domestic properties with sole occupants. Councils are also required to provide discounts to vulnerable retired people on a means tested basis. Billing authorities also have a local policy that provides council tax discounts to vulnerable people of working age, again on a means tested basis.

The key benefit of the council tax as a system of raising money is that it is very difficult to evade, as houses tend to move far less than people. Thus, it is comparatively easy to bill and has a very high collection rate of 97 per cent or above in most council areas.

How is the council tax calculated?

Every domestic property is valued by the Valuation Office Agency and placed in one of the eight valuation bands, based on its value as at 1 April 1991 (houses built after this date have their value as at April 1991 estimated at the time of their first sale). The amount of council tax paid varies according to the valuation band as follows:

| Band | Value at 1 April 1991 | Ratio | Ratio as a percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | Up to £40,000 | 6/9 | 67% |

| B | £40,001 - £52,000 | 7/9 | 78% |

| C | £52,001 - £68,000 | 8/9 | 89% |

| D | £88,001 - £120,000 | 9/9 | 100% |

| E | £88,001 - £120,000 | 11/9 | 122% |

| F | £120,001 - £160,000 | 13/9 | 144% |

| G | £160,001 - £320,000 | 15/9 | 167% |

| H | £320,001 and above | 18/9 | 200% |

Council tax is usually expressed as ‘Band D equivalent’. The average council tax for each council area differs for Band D depending on the number of properties in each band. Properties in Bands A-C pay less than the standard council tax and those in Bands E-H pay more.

Originally, central Government planned to conduct regular revaluations of the council tax bands to make sure that they kept pace with house inflation. Such revaluations proved to be politically difficult and so there has been only one in Wales (April 2005) and one in Scotland (April 2017). There has never been a revaluation in England.

As new homes are built, each is valued for council tax purposes at 1991 prices and added to the council’s council tax base. Every year, councils review their council tax base and consider whether they need to increase the level of council tax to fund their spending plans. This is an important part of the budget process as it is illegal for councils to raise additional council tax through supplementary bills part way through the year.

Increases in council tax always are of public interest and so successive governments have sought to limit the size of any annual increase in council tax that can be agreed by the council. The current system of control was introduced by the Localism Act 2011 and requires the council to win a simple majority in a local referendum for any proposed council tax increase that is considered excessive by central government. The government announces as part of the local government settlement the percentage increase that it considers excessive and, therefore, would trigger a referendum. For 2018/19 this is three per cent or £5 for district councils, whichever is the higher. Parish and town councils are currently not affected by this restriction and can raise their council tax precept by as much as they wish.

In recent years, central government has also allowed councils with adult social care responsibilities to raise additional council tax that is ring-fenced to the provision of adult social care services.

How is the council tax billed?

To ensure that residents only receive one council tax bill, every local area has one council that acts as the billing authority, with all of the other councils in the local area being precepting authorities. Each precepting authority notifies the relevant billing authority of their decisions on council tax and the billing authority prepares one bill covering every council’s tax. In two tier areas the billing authority is the District Council.

Each billing authority operates a collection fund that accounts for all the council tax payments as they are received from residents and then the funding is distributed to the relevant precepting authorities on the basis of the demand made at budget time.

In a single tier area, the metropolitan or unitary council acts as the billing authority. In a two-tier area, the district or borough council acts as the billing authority.

Precepting authorities include: county councils, police and fire authorities, parish and town councils and combined authorities.

The New Homes Bonus

Building new homes leads to an increase in the council tax base and so enables the council to raise more funding for services. In addition to increased council tax, central government currently gives a financial incentive to councils that build new homes with an additional amount of government grant, known as the New Homes Bonus.

The grant has been given since 2011 and originally provided councils with grant equivalent to the council tax on each and every new property for six forward years. Recently, however, the government have made the bonus less generous and, for 2018/19, the new homes bonus will only be paid for four years and only for the number of homes built above a national baseline of 0.4 per cent of the total local housing stock. In two-tier areas, the district council receives 80 per cent of the New Homes Bonus and the county council receives the remaining 20 per cent. The rationale for this 80:20 split is that since district is the planning authority it is the council that needs to be incentivised to agree new housing.

Business rates

Local councils levy a business rate on every business premises in their area. The amount of the charge is based on:

The Rateable Value of the business premise (set nationally by the Valuation Office Agency on the estimated rental value of the premises)

Multiplied by

A Business Rate Multiplier (of x pence in the £)

Billing authorities raise the rates bill and collect the income, but do not retain the money themselves. The way in which business rates income is shared between councils has been subject to change over the years and is currently a live issue of debate.

The key problem is one of ‘fairness’. Individual councils have vastly different business communities and so have varying abilities to raise income from business rates. However, a significant amount of local government expenditure provides services to local people rather than local businesses (for example on social care) and it may not always be seen as ‘fair’ to enable local councils simply to determine, raise and spend business rates locally.

| Prior to 1990 | Councils were free to set the business rate multiplier locally. |

|---|---|

| 1990-2012 | Government set the business rate multiplier nationally. Rates income was pooled nationally and re-distributed to councils via the government grant system. |

| After 2012 |

|

| The future? | The government has piloted a new system where some local councils retain more than 50% of any growth in business rates locally. The intention is to move to a revised system nationally but this has now been deferred. |

Further detail of the current system

Local shares of business rates

The total business rate levied in any local area is shared 50:50 between central and local government. However, the 50 per cent local share is then distributed between the billing and some of the precepting authorities depending on the structure of the government in the local area. Shares are distributed as follows:

| In unitary and metropolitan areas |

|

|---|---|

| In London |

|

| London Authority In two-tier areas |

|

Police and crime commissioners and parish councils do not receive business rates funding.

Case study: Epsom and Ewell District Council

In 201/18, 40 per cent of the council’s business rate income was approx. £9.76 million. However, the council pays a ‘tariff’ to central government of approx. £8.43 million leaving the council with £1.33million of income.

Case study: Oldham Metropolitan Borough Council

In 2016/17, 49 per cent of the council’s business rate income was approximately £29.06 million. However, the council receives a ‘top-up’ from central government of approx. £30.24 million, leaving the council with approx. £59.3 million of income.

Business rates and risk

From 1992–2012, the national system meant that any local changes due to business closures or successful business rates appeals were dealt with at national level. Under the current system, any appeal that is successful has a local impact on the council’s funding levels. To offset some of this risk, some councils have joined together, usually in county areas, and formed voluntary business rates pools, which aim to spread such risk over a larger number of individual councils.

Government grants

During the 20th century increasingly it was found that the costs of services provided by local authorities exceeded the revenues raised from local taxes. Accordingly government gradually increased the funding provided from treasury sources. Since 2010 this process has reversed. Local government receives two types of government grant income:

Revenue Support Grant (RSG): this is a general grant calculated on the basis of the spending need at the individual council. The grant can be spent on any service according to the objectives and priorities of the local council.

There are two factors that affect the size of such grants:

- The total amount of funding the government wishes to provide to all local councils in total

Since 2010 the government has significantly reduced this sum and the intended policy aim had been to completely remove RSG from 2020, but it is now expected to continue for at least a few more years. Since 2010, government has reduced the level of grant income provided to local councils as part of government austerity and some councils now usually receive zero RSG each year. The exact nature of arrangements are finalised each year in the Local Government Finance Settlement which is usually announced for the financial year ahead in December and finalised in January.

- The relative size and distribution of the total grant sum between councils

This is always a controversial area and requires government to ‘model’ spending need in a local area and then consider whether there is a gap between local sources of funding and this spending need, the gap being the grant sum paid. Most governments have sought to model funding requirements using local factors such as population size, relative deprivation and urban v rural location. Recent approaches have also taken into consideration the councils total income requirement when calculating RSG. Therefore, councils with a high council tax base receive less government grant due to their increased ability to raise money locally.

The current system of business rates top-ups and tariffs is also based on distributing funds between councils and so the way these formulae operate is still of importance to local councils.

Specific grants

Central government also provides additional grant funding to local councils but they restrict the use of such grants to specifically defined service areas. For example, public health grant, which must be spent on providing a range of local public health services defined by government. The same is the case with ‘Dedicated Schools Grant’ which can only be spent on providing schools

The key issue here is that local councils are not fully in control of determining how local need can be met as there are national rules over the use of such funds. Accordingly, since 2010, the government has generally moved away from providing specific grants as part of a drive to a more local approach. The Department for Education being an exception to this.

Fees and charges for service use

Councils provide a range of statutory services and the law usually determines whether a council should make a charge for service use, and, if so, how much can be charged. For example:

- The Libraries and Museums Act 1964 restricts the council from making a charge for a book lending service, but allows councils to make charges for other services, for example CD/DVD lending and room hire.

- The Town and County Planning Regulations 2012 set out the actual charges that every council should levy for various types of planning application.

- The Care Act 2014 enables councils to require people who receive adult care services to contribute to the cost of the service they receive. The level of contribution is determined by a financial assessment of the individual’s financial means.

Section 93 of the Local Government Act 2003 enables councils to charge users for discretionary services, including car parking, leisure and cultural activities. Where levied charges should not be higher than necessary to cover the total cost of providing the service. Councils can make profits from charging for discretionary services but only if they provide them through an arm’s length company.

Over recent years, councils have become more focussed on service charges and most now have regular policy discussions over whether or not to charge for services. This is usually undertaken as part of the overall budget making process.

In setting fees and charges, councils should not only consider the total cost of the service and whether any subsidy from general funds such a council tax is justified but also the effect of any charge on service use. For example, should a service such as pest control be provided without charge (or at a nominal fee) to encourage the public to report infestation? Should the council consider accessibility to vulnerable groups when they set charges? Should the council discourage long term parking in city centre car parks by levying high fees for long stays?

Other sources of income

Other potential income sources available to councils include:

- Returns and interest from investments

Councils may invest any surplus cash in interest bearing investments. Any such interest and other financial return can be used by the council to finance revenue expenditure. However councils may not borrow to invest in this way.

- Commercial income

Many local councils are using the extended flexibilities of the Localism Act 2011 to offer a variety of service through commercial arrangements with external bodies. Whilst such arrangements may not have the explicit aim of generating income for the council, returns in the form of profit or dividend income from local authority companies or other trading activities can be added to the overall revenue budget.

- Fixed Penalty Notices

These can be issued by local councils for a variety of environmental offences such as dog fouling, fly tipping and littering. Government controls the maximum that can be charged for such penalties and also must demonstrate that it uses the income to fund a defined range of activities. For example, dog control offences have a penalty of between £50 to £80, with the proceeds restricted to provide litter, dog control, graffiti and fly-posting services.

Challenge 4

If you have been working through this workbook, you should already have obtained a copy of your council’s MTFS and annual budget. You will need a copy of them to complete this challenge. As you work through this section, find the level of income your council raises from each of the sources mentioned and consider the local constraints on each.

- What (if any) council tax increase did your council agree last year? What was its reasoning behind this decision?

-

How much New Homes Bonus has the council received over the past three years? How does your council spend the money? Is it added into the overall budget or spent on certain one-off items?

-

How much income from business rates does your council receive? How is it affected by the top-ups and tariffs system?

-

Is your council part of a business rates pool? Why is it, or isn’t it part of such a pool?

-

How does your council decide on which service to charge for? Are there any services that your council might charge for but currently chooses to offer without charge? Why?

-

Advanced challenge – try to plot a chart showing the amounts of each type of income over the past five years. What do you notice about the pattern and trend?

The sources of capital funding

This section provides an overview of potential sources of capital income for local councils. You will recall that capital income is largely restricted to funding capital expenditure, such as the provision and refurbishment of assets. From

2018/19 councils will be required to produce an annual capital strategy, approved by full council. It is likely this will be done alongside the budget and associated papers.

Key capital funding sources are outlined below.

Capital receipts are the proceeds of sale that are generated when a council sells an asset, such as land or buildings. The amount of capital receipts the council can generate will depend on the assets that the council are willing to sell and the buoyancy of the market for such assets. A key consideration when selling council assets is the revenue income and expenditure forgone. For example, if a council decides to sell a block of industrial units, it will gain a capital receipt but forgo any rental income that would be paid by tenants.

Rules are somewhat different in the Housing Revenue Account, where capital receipts generated under Right To Buy legislation are subject to control by central government. Many councils have an agreement to utilise these capital receipts locally to part-fund new social and affordable housing, but, if the council is unable to use such receipts over an agreed timescale, they are returned to central government.

Government grants are available to local councils for certain kinds of capital expenditure, usually either transport or school related expenditure. In most cases, grants will fund or part-fund the initial building or acquisition of the asset but provides no funding on ongoing revenue expenditure such as maintenance and running costs.

Borrowing - since 2003, local councils have been able to borrow to fund capital expenditure. According to CIPFA’s Prudential Code, all council long term borrowing must be both ‘affordable’ and ‘prudent’. Therefore, the council must be confident that it is able to pay back both the interest and principal of any borrowing through its revenue budget. Whilst new borrowing will enable the council to construct useful assets, it will also lead to an increased ‘call’ on revenue budgets for many years into the future and so, through a rigorous process of project appraisal and budgeting, the council determines that it is not over-stretching itself financially.

The overall amount of new borrowing councils can enter into in the Housing Revenue Account is currently capped by central government.

Use of reserves given the low level of return available through investment income, many councils are looking to use their reserves in a more creative manner to maximise value for money. Councils may use funding from their reserve accounts to spend on capital. Many councils no longer do this to a great extent because of the pressure that has been placed on revenue budgets in recent years.

Planning gain most councils require private developers to contribute to the overall public realm as part of larger construction projects. There are two main ways of doing this:

- Section 106 agreements: The Planning and Land Act 1992 (sec 106) enables councils to negotiate with developers to either directly provide affordable housing and public realm, or to provide monies to the council so that they can provide whatever has been agreed.

- The Community Infrastructure Levy: this is a tariff-based charging scheme that provides funding for more general infrastructure improvements. It is a voluntary scheme and the council must have any proposed CIL scheme inspected and approved.

Challenge 5

Obtain a copy of your council’s latest Capital Programme (the budget for capital expenditure and income) and Capital Strategy (from 2018/19 onwards) From this you will be able to see the various capital schemes that your council plans to provide and how the overall programme is intended to be funded.

Advanced challenge – try to track the various levels of expenditure and funding over the past five years – what do you notice?

Provisions, reserves and balances

A budget is a financial plan and like all plans it can go wrong. Councils therefore need to consider the financial impact of risk and they also need to think about their future needs. Accounting rules and regulations require all organisations to act prudently in setting aside funding where there is an expectation of the need to spend in the future. Accordingly, local councils will set aside funding over three broad areas:

Reserves

Councils create reserves as a means of building up funds to meet know future liabilities. These are sometimes reported in a series of locally agreed specific or earmarked reserves and may include sums to cover potential damage to council assets (sometimes known as self-insurance), un-spent budgets carried forward by the service or reserves to enable the council to accumulate funding for large projects in the future, for example a transformation reserve. Each reserve comes with a different level of risk. It is important to understand risk and risk appetite before spending

These reserves are restricted by local agreement to fund certain types of expenditure but can be reconsidered or released if the council’s future plans and priorities change.

Balances

The above are specifically allocated to pay for future liabilities. However, every council will also wish to ensure that it has a ‘working balance’ to act as a final contingency for unanticipated fluctuations in their spending and income.

The Local Government Act 2003 requires a council to ensure that it has a minimum level of reserves and balances and requires that the Section 151 officer reports that they are satisfied that the annual budget about to be agreed does indeed leave the council with at least the agreed minimum reserve. Legislation does not define how much this minimum level should be, instead, the Section 151 officer will estimate the elements of risk in the council’s finances and then recommend a minimum level of reserves to council as part of the annual budget setting process.

Confusingly, some councils refer to balances as reserves, general reserves or un-allocated reserves.

Why have reserves?

There are no legal or best practice guidelines on how much councils should hold in reserves and will depend on the local circumstances of the individual council. The only legal requirement is that the council must define and attempt to ensure that it holds an agreed minimum level of reserves as discussed above. When added together, most councils have total reserves in excess of the agreed minimum level.

In times of austerity, it is tempting for a council to run down its reserves to maintain day-to-day spending. However, this is, at best, short sighted and, at worst, disastrous! Reserves can only be spent once and so can never be the answer to long-term funding problems. However, reserves can be used to buy the council time to consider how best to make efficiency savings and can also be used to ‘smooth’ any uneven pattern in the need to make savings.

Treasury management

The various reserves held by the council are invested in order to make a return that itself can be spent on providing public services. All investments carry risk and the more risk that is taken in an investment the more return is possible. However, the likelihood of losing all or part of the principal sum invested increases. Councils are investing public money and so it is essential that councils consider the security of such investments ahead of the return that might potentially be made. The Treasury Management Strategy, agreed annual by full council, considers the overall approach taken by the council when managing its cash, investment and borrowing activities. It will provide parameters on the types of investment the council will consider and whether any new borrowing is anticipated over the forthcoming few years.

The council’s finance function will include specialist officers who look after the council’s treasury management activities. There are three elements of such activity:

- monitoring the council’s cash flow and bank accounts – like every organisation, making sure that the banks statement is regularly reconciled to the council’s accounts system is a basis requirement of financial control

- making detailed investment decisions on behalf of the council, in accordance with the principles agreed by the council in its annual Treasury Management Strategy

- making detailed borrowing decisions, again in accordance with the Treasury Management Strategy.

As well as the annual strategy, treasury management activities will be reported to council at least in a mid-year update and an annual report after the year end. In practice, many councils provide quarterly reports on such activities.

Challenge 6

Find out what reserves your council holds and the purpose of each of these reserves. Most annual budget reports will detail such information, but there is also a note in your published annual accounts that will detail reserve levels at the year end. What do you notice in what you find?

Governance and audit

Governance is about how councils ensure that they are doing the right things, in the right way, for the right people, in an accountable manner. As such, financial control forms an important aspect of the overall governance framework at every council.

Every elected member is responsible for making sure that the council is effectively governed. Councils deal with public money and so it is essential that there are well constructed and documented systems and procedures to ensure that the council not only acts as a good steward but also exhibits the values and culture required to foster good governance. Such values are summed up in the ‘seven principles of public life’ (selflessness, integrity, objectivity, accountability, openness, honesty and leadership) set out by Lord Nolan in 1995[1].

It is best practice for councils to have an Audit Committee (or an equivalent committee) that is made up of councillors, and sometimes independent non-councillors, to consider governance issues in detail. This committee is an important aspect of the governance framework at the council as it sets the tone from the top and will have the power to make recommendations to full council, the executive or to whomever it considers best placed to deal with the committee’s concerns. The Audit Committee (or equivalent) is likely to deal with the following issues:

- ensuring the council has a comprehensive set of procedures and rules, such as financial regulations

- discussing the work of internal and external audit, and other inspection agencies as appropriate

- risk management policies and procedures

- reviewing, and in some councils approving, the annual financial statements

- reviewing the annual governance statement.

If an audit committee is not established its functions must be carried out by full council. Section 3 of the Accounts and Audit Regulations (2016) requires that the council ‘must ensure that it has a sound system of internal control’. This system should ensure that the financial and operational management is effective, including the management of risk. The regulations make the council’s responsible financial officer responsible for ensuring that there are effective accounting recording and control systems are in place. Such controls are documented in the council’s Financial Regulations, which form part of the council’s overall constitution.

The Accounts and Audit Regulations also require that the council conducts a review of the effectiveness of its system of internal control each financial year and prepares an annual governance statement that summarises the governance arrangements present at the council, concludes on the effectiveness of such arrangements and includes an action plan for any improvement that is necessary. This statement is signed by the leader of the council and the chief executive officer as a sign of its importance.

The annual financial statements

Every council, by law, must prepare, have audited and then publish a set of annual financial statements. The format of these financial statements is informed by CIPFA’s Code of Practice on Local Authority Accounting in the UK to ensure that they are similar across all councils.

The audited financial statements must be approved by elected members as they represent the main document that demonstrates to the public how public money has been allocated to services over the year. However, they tend to be long and technical documents and are a challenging read! However, the financial statements include a narrative report provides a useful overview of the council’s finances for the past year and into the future in an accessible style and should be essential reading for all councillors!

Audit

The Accounts and Audit Regulations 2016, require councils to have two types of audit, internal and external audit. Their role is outlined below.

Internal audit

Internal audit provides assurance to councillors and officers that the council’s various internal control processes and procedures operate in an effective an efficient manner. They fulfil this role by preparing a risk-based audit plan that carries out independent reviews of the council’s activities.

Whilst an effective internal audit function is essential, the way such a service is provided is determined by the council. Some councils have their own internal audit department, some use internal audit partnerships and others use private audit companies. Whichever approach is used, the work of internal audit is important as it operates ‘on the ground’ providing detailed support and challenge directly to officers about their detailed governance arrangements.

Internal audit findings and recommendations will be reported in detail to the officers who are responsible for managing the section of the council under review. Internal audit will also summarise their work in regular, usually quarterly, reports to the audit committee.

External audit

External audit’s responsibilities are set out in the Local Audit and Accountability Act 2014. Broadly speaking, these responsibilities are:

- to provide an opinion on whether the council’s Annual Financial Statements provide a true and fair view of the council’s finances

- to provide an opinion on whether the council has made proper arrangements for securing economy, efficiency and effectiveness in its use of resources

- to give electors the opportunity to raise questions about the council’s accounts and consider and decide upon objections received in relation to the accounts

- to apply to the court for a declaration that an item in the accounts is contrary to the law.

In order to undertake their work, external auditors will need to satisfy themselves that the council’s governance and internal control systems are sound. Therefore, they will review the work of internal audit and seek to place reliance on the conclusions made. This avoids duplication of audit effort.

Senior representatives of external audit will regularly attend the council’s audit committee and share their audit plans and approach as well as their findings and recommendations as set out in the annual audit letter.

Challenge 7

-

Obtain the latest annual financial statements and read the narrative report.

-

What are your conclusions? Make a resolution to read this narrative report every year from now on!

-

Obtain the latest annual governance statement (which is published as part of the annual financial statements). What governance issues have been highlighted?

-

Obtain your council’s latest external audit letter. What assurance does it give you that the council’s financial affairs are well governed?

Notes

[1] First Report of the Committee on Standards in Public Life (1995) p14.

Further information and support

Useful websites

The LGA website is an invaluable source of help and advice for all those in local government. From the home page, one of the topics deals specifically with finance and business rates and provides a wealth of information, publication and case studies.

The website of the Chartered Institute of Public Finance and Accountancy is a useful source of more detailed financial discussion and guidance.

The Local Government Information Unit provides various publications and training seminars on various aspects of local government finance.

Further training

The LGA finance leaders seminar is a two-day event for councillors who have specific responsibility for finance, whether as a council leader, portfolio holder of chair of an audit or scrutiny committee. The event is usually held three times in the autumn. Details can be found on the LGA website.

Glossary of terms

Annual Governance Statement an annual report prepared, approved and published with the financial statements that reviews the council’s overall governance arrangements.

Best Value the legal duty introduced in the Local Government Act 1999 that requires councils to make arrangements to continuously improve the way in which its functions are exercised and to have regard to a combination of economy, efficiency and effectiveness.

Billing authority a local council that directly bills council tax and business rates in its local area.

Budget gap where the estimates expenditure is higher than the estimated income in a budget or other financial plan, there is said to be a ‘budget gap’.

Budget outturn the actual income or expenditure compared to the budgeted sum at the end of the financial year. This is usually reported to councillors soon after the close of the financial year in the ‘outturn report’.

Business rateable value the annual assumed rental value of a business property.

Business rate multiplier the annual amount established by central government used in the calculation of the business rates bill. This amount is multiplied by the businesses rateable value to derive the size of the business rates bill for the year.

Business rates pools an agreement between neighbouring councils to add together combine their business rates activities in a pool. This is designed to maximise the ability for councils to retain business rates locally.

Capital receipts the proceeds of sale from the disposal of assets such as land and buildings.

Council tax base the total amount of council tax due to the council. This is calculated by multiplying the number of domestic properties in each of the 8 council tax bands and then adding the resultant figures together. The tax base can increased by building new homes as well as by increasing the council tax demand itself.

De-minimis literally means ‘too small’. Councils will usually set a de-minimis level where small value assets (usually equipment) are treated as revenue expenditure rather than capital expenditure.

Discretionary services a range of services that councils provide which they are not required to provide by law.

Earmarked reserves an amount of money that has been set aside to be spent on a defined activity or manner at some point in the future. Also known as specific reserves.

General fund the council’s main account detailing its expenditure and income on services, except those arising from the provision of housing accommodation directly by the council.

Housing Revenue Account (HRA) a separate account to the General Fund, which includes the expenditure and income arising from the provision of housing accommodation directly by the council.

Internal borrowing where a council decides to use its reserves to finance expenditure rather than borrow externally.

Internal control a system of rules, systems and procedures intended to make sure that the council’s financial activities are well managed.

Local government settlement the annual announcement by Government of the amount of grant funding to be provided for the forthcoming year. The provisional settlement is usually announced in mid-December, with a final settlement confirmed in mid to late January.

Medium Term Financial Strategy (MTFS) a budget estimating income and expenditure at a high level over at least three forward financial years.

Narrative report an element of the council’s annual financial statements providing an overview of the council’s finances and financial provision in an accessible format.

Precept the amount which a local authority which cannot bill the council tax directly requires to be collected on its behalf by the relevant billing authority.

Prudential borrowing/The Prudential Code the CIPFA Code of Practice that regulates local council capital spending and financing. Requires all borrowing to be both affordable and prudent.

Responsible financial officer the proper name for the ‘Section 151 officer’. Every council, by law will designate an individual officer as having legal responsibility over providing effective financial management and advice across the council. The post holder must be a qualified member of one of the main accountancy bodies in the UK.

Revenue Support Grant the main grant paid to councils by central government. The amount of this grant has been severely reduced since 2010.

Section 151 officer another name for the responsible financial officer. Derived from the fact that section 151 of the Local Government Act 1972 requires there to be such an officer at every council.

Self-insurance the process used by many councils to use a specific reserve to set aside money to repair or replace any damage that occurs where there is no external insurance policy to cover the loss.

Specific Government Grant money provided by central government to local government where there are specific requirements for councils to spend the money on certain defined activities.

Statutory services services which councils must provide by law.

Responsible financial officer a senior officer who is legally responsible for the overall administration of the council’s financial systems, controls and procedures. Also known as the ‘Section 151 officer’

Ring-fenced funding, budgets etc income and expenditure budgeted and spent on certain defined activities and cannot be used elsewhere.

Answers to challenge 2

Which of the following transactions are revenue and which are capital?

- Filling in a small pot-hole in a council car park?

This is repairs and so is revenue. - Re-surfacing the entire car park?

This improves the asset and so is capital expenditure. - The annual cost of the council’s refuse collection contractor, who operates the service under a seven-year contract?

It is the subject of the expenditure not the length of the contract that is crucial here. Refuse collection is an on-going regular service and so is revenue expenditure. - Adding webcasting equipment to the council chamber costing £50,000?

This is likely to be capital expenditure as the cost is almost certainly above the council’s "de minimis" limit. - Redundancy costs of officers as part of a re-structuring programme?

Whilst redundancy costs are staff related and so revenue expenditure, if the re-structure is agreed to be a transformation project then the council may use its capital resources for this if it wishes.