Introduction and executive summary

The Chancellor is conducting the 2021 Spending Review in exceptional conditions. We are dealing with the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on people, the economy and public finances. But this is also the time to be bold and ambitious about reshaping the direction of this country for years to come.

Councils have played a critical role throughout the last eighteen months, turning rapidly changing policy into practice on the ground. The experience of the pandemic demonstrates that local government is a trusted delivery partner for Whitehall, making sure that our joint response to this crisis recognised local needs and impacts across our diverse communities.

By central and local government working together, tens of thousands of rough sleepers and homeless people were helped off the streets, millions of our most vulnerable were shielded from the virus and over £20 billion in vital grants were provided to businesses forced to close or restrict their activities. Councils, with their directors of public health, have been at the centre of efforts to limit the spread of COVID-19 in all its variants and support our hugely successful vaccination programme. Throughout, councils learnt from and supported each other through sector-led improvement.

Due to rapid change brought in by COVID-19, for many people their local area matters more now than it ever did, and will continue to play a significant role as we move further into recovery. Some groups and communities have been adversely affected by the health, social and economic impacts of the pandemic and will need more help to recover, with some individuals needing support where they did not prior to the pandemic. For others, the issues they faced pre-pandemic – access to fast broadband, housing that is right for them and their families – have been amplified.

This means that the role councils play will have an even greater significance in the lives of people as we all reimagine what our post-pandemic lives look like. We need a collective effort to rebuild our economy, get people back to work, level up inequalities across the country and create new hope in our communities. Responding to the significant economic challenges ahead requires a renewed joint endeavour between local and national government as equal partners. Building back better means building back local.

The Government has set an ambitious target to level up the entire country and improve the lives of its citizens. The Prime Minister was clear that to make progress on levelling up we have to raise living standards, spread opportunity, improve our public services and restore people’s sense of pride in their community. All of these aims need the necessary funding, and councils to be empowered to help deliver on this shared commitment.

It is clear that the starting point for this new approach to our public services, a joint endeavour with national government, needs to be a re-think of public finances with a multi-year financial settlement providing local government with certainty over their medium-term finances; sufficiency of resources to tackle day-to-day pressures and the lasting impact of COVID-19; and that recognises the benefits of investment directed by those closest to the opportunities for shared prosperity.

To achieve this, the Spending Review will need to move away from the traditional drivers of departmental spending towards a degree of fiscal decentralisation in line with some of the world’s most productive economies. The economic challenges our communities are facing requires a bold response – place-based budgets which are in tune with the needs of the local economy. We need to re-think how we fund public services, not try to fit new and bold ideas into old frameworks.

This Spending Review presents an opportunity to reset public spending in a way that is fit for the future, flexible to allow for the delivery of local priorities, and empowers councils to achieve the ambition for our communities that central and local government share.

This submission is organised into six priority themes which set out how local government can act as the driver to our shared priorities, in addition to a series of departmental supplements with further suggestions on how local government can work with all parts of Whitehall to deliver policy.

These proposals include a mix of revenue funding, capital funding, freedoms and flexibilities as well as policy reform to relieve pressures on local government (for example, services to children with special educational needs and responsibilities.

Priority 1 – A strong and certain financial foundation

The Spending Review needs to provide councils with sufficient funding to meet cost pressures and pre-existing challenges, but is also an opportunity to enable councils to bring together the budgets of public services across a place to eliminate duplication of effort and drive savings to the public purse.

Key proposals include:

- A multi-year ‘core’ local government funding settlement which provides sufficient certainty and resources. Excluding the impact of COVID-19 and pre-existing challenges, such as pressures arising from the education of children with special educational needs and disabilities (SEND) or the pre-existing adult social care provider market, we estimate councils are facing cost pressures of £2.6 billion each year, comprising £1.1 billion for adult social care and £1.5 billion for other services, just to keep them at their 2019/20 level of quality and access.

- Our plan to allow councils to deliver further public spending efficiencies by joining up local services in a place and eliminating the fragmentation of funding.

- Our proposals to reform and improve local taxation, as well as using the business rates review as an opportunity to discuss how council funding can be further diversified through other forms of taxation.

Priority 2 – Adult social care and public health

The Government’s publication of ‘Build Back Better: Our plan for health and social care’ (the plan) was an important moment in the long-running debate about the future of adult social care and support. It has the potential to be an important first step in moving toward the changes that are needed to ensure people of all ages are best supported to live the life they want to lead. However, if the plan’s potential is to be realised, the Spending Review must deliver new national funding to stabilise the service. Public health services have shown their value during the pandemic and are key to tackling health inequalities. This is about securing the resources needed to deliver on existing priorities and responsibilities – both now and in the coming years. But it is not an end in itself; such investment will also secure the foundations for other activity we want to take forward now and in the future. These are set out in Priority 3, including our ambitions to narrow inequalities.

Key proposals include:

- A £1.5 billion injection of funding to stabilise the adult social care provider market, together with annual funding needed to meet the cost pressures covered above.

- Investing £900 million in the public health grant to return it to its 2015/16 level in real terms.

Priority 3 – Investing in communities and tackling health inequalities

The concept of levelling up is multi-faceted and will require investment in social as well as physical infrastructure. It is vital that central and local government work together on these multiple issues, in a unique mix in each local area, at the same time.

The Spending Review is an opportunity to put a fresh and innovative approach into action by introducing an unringfenced and ongoing Community Investment Fund, worth £1 billion in 2022/23 and increasing to £3 billion by 2024/25, so that councils can invest in supporting individuals and strengthening communities according to priorities in their local areas, including tackling health inequalities.

Priority 4 – Reaching net zero

Climate change is one of the most important issues facing the world today and councils are leading the way in helping the Government meet its ambition for net zero by 2050.

Key proposals include:

- A call for a new policy and fiscal framework, backed by crucial investment, to allow councils to help Government achieve its aim for the UK to become a net zero carbon economy in 30 years’ time.

- Measures to make sure that the ambitious waste and recycling reforms are introduced in a financially sustainable fashion.

Priority 5 – Education and children’s social care

Councils are ambitious about maximising the life chances of all children, regardless of their background. Equality of opportunity is a critical element of enabling levelling up and building thriving local areas.

Key proposals include:

- Measures to empower councils to build new schools in their areas, as well as the financial capital funding framework needed to support it.

- Dealing with pressures related to the education and care of children with SEND.

Priority 6 – Building back local economies

Councils want to work with Government on the economic recovery from COVID-19 as trusted partners, in particular through greater devolution and powers to steer resources to local economic priorities.

Key proposals include:

- Dedicated local growth funding through the Shared Prosperity Fund and other initiatives.

- An innovative, devolved approach to making sure that local residents have the right skills to match the work opportunities of the future.

- Measures to help councils secure affordable homes for all those who need it, including a housing stimulus package to deliver 100,000 homes each year and reform of the Housing Revenue Account system.

Priority 1 - A strong and certain financial foundation

Cost pressures

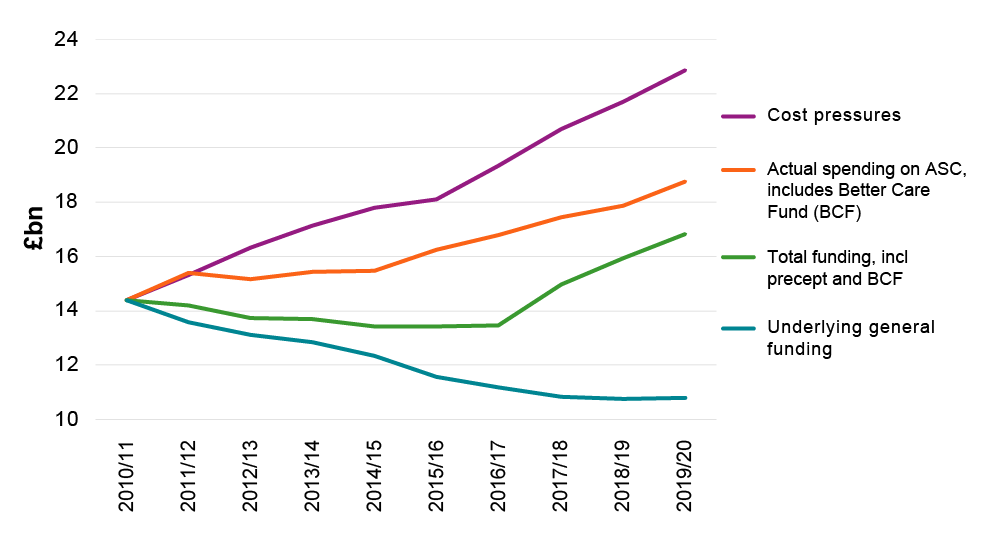

Recent Local Government Association (LGA) analysis estimates that the average increase in annual cost pressures facing councils is £2.6 billion per year to maintain services at their current level of access and quality, meaning that the same services will cost around £7.8 billion more to provide in three years’ time. Of this, £1.1 billion per year is related to adult social care (in addition to a pre-existing £1.5 billion provider market pressure), £0.6 billion to children’s social care and £0.9 billion to all other council services (excluding education and police/fire services).

This does not include any continued impact of COVID-19, for example the health impacts of ‘long COVID’, catching up on pent up demand in children’s social care, or the longer-term effects on sales, fees and charges or commercial income.

For all these pressures to be met through council tax alone, income from council tax would have to increase by 8 per cent each year, which is not sustainable. However, if no funding is found, councils would have to make savings worth the entirety of their spending on museums, sports facilities, swimming pools, libraries and parks – each year.

| 2021/22 | 2022/23 | 2023/24 | 2024/25 | Average annual increase | Change 21/22 to 24/25 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adult social care | 20.0 | 21.1 | 22.3 | 23.3 | 1.1 | 16.6% |

| Children's social care | 10.9 | 11.4 | 12.1 | 12.6 | 0.6 | 15.9% |

| Homelessness | 0.9 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 0.1 | 27.2% |

| All other services (excl. education, police and fire) | 20.1 | 20.9 | 22.1 | 22.6 | 0.8 | 12.5% |

| Total net expenditure (excl. education, police and fire) | 51.8 | 54.3 | 57.5 | 59.6 | 2.6 | 15.0% |

Other underlying pressures

As in previous years, no improvements to services are included – the £2.6 billion annual average cost pressures are related purely to increased demand and costs of providing the same services, rather than expanding access or increasing the quality of services which would come at additional cost. Underlying problems with services, such as the provider market pressure in adult social care or the remaining SEND service funding deficits held by councils, would stay at the same level as previously, without making it better or worse. Further funding injections would be required to deal with these challenges, or future pressures in these challenges, should they grow.

The following table shows this funding requirement including cost pressures:

| 2022/23 £bn |

2023/24 £bn |

2024/25 £bn |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Cost pressures (average of £2.6bn per year as above) | 2.5 | 5.7 | 7.8 |

| Existing adult social care provider market pressures | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 |

| Existing pressures on children's social care | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Existing pressures on homelessness | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| Addressing the public health service underfunding | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.9 |

| SEND deficits not met by funding | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 |

| Total core revenue funding need | 6.7 | 9.9 | 12.0 |

While the list above covers key identifiable underlying pressures, it is important to note that there are other specific pressures and new burdens, the funding of which falls on core council resources and are more difficult to quantify. They are identified, where relevant, elsewhere in the submission.

Special educational needs and disabilities

The cost pressures set out previously exclude education, and in turn special educational needs and disabilities (SEND), owing to the difficulty in separating local government responsibilities and expenditure from other school and local education authority (LEA) expenditure. However, the ongoing financial impact of SEND must not be understated. The number of children and young people with Education, Health and Care Plans (EHCPs) has risen year on year for the past decade, with an 11 per cent rise in the last year alone. Although the future costs of SEND are difficult to pin down, research from ISOS commissioned by the LGA in 2018 shows that from 2015/16 to 2018/19 expenditure increased by 17 per cent across the 93 authorities which responded to a survey.

Government has provided additional funding for SEND of £250 million over 2018/19 and 2019/20, and £700 million in 2020/21. However, despite this additional funding, there remains an estimated funding gap of £0.6 billion by 2021.

Furthermore, these one-time cash injections, although welcome, have not been formally included in the baseline of the High Needs Block funding provided to councils, meaning that funding continues to further lag behind costs. Whilst annual increases in High Needs Block resources is welcomed, it does not go far enough to keep pace with demand. Moreover, there is uncertainty in the funding councils will receive, despite the trend in EHCP numbers, resulting in difficulty managing future risks from an already squeezed system.

COVID-19

Local government has coordinated and delivered the national government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic at a local level. Working with national government, councils have drawn on strong local leadership coupled with exceptional commitment from councillors and council staff to protect the most vulnerable in our society and ensure vital services continue to be provided, showing what can be achieved when we work together towards a shared goal.

Central and local government have protected rough sleepers and homeless people, helped those defined as clinically extremely vulnerable (CEV) to shield to protect themselves from the virus, set up effective local virus tracing partnerships, supported businesses with vital grants, and helped distribute the largest vaccination programme in our history. Local government can be, and has been, trusted to deliver on national priorities.

For many people their local area matters now more than ever, with an emphasis on the value of green spaces, safe communities, and efficiently run public services. For some, the issues they faced pre-pandemic – access to fast broadband, appropriate housing – have been amplified. The role councils play will have a greater significance in the lives of people as we emerge into the post-pandemic era.

The pandemic has caused extraordinary financial costs to local government. Councils reported to Government, the financial impact of COVID-19 in 2020/21 was an estimated £9.5 billion (consisting of £6.8 billion of cost pressures and £2.7 billion of non-tax income losses). In addition, councils estimate £2.2 billion of lost local tax income. Central government has supported councils financially, with £8.5 billion of grants as well as compensation schemes for a proportion of lost sales, fees, and charges, and local tax income.

The effects of COVID-19 will be felt far beyond the end of the current phase of the pandemic.

- Economic vulnerability and the long-term health effects some people experience from COVID-19 will continue to hinder society’s full recovery.

- Council delivered adult social care and mental health services will play a pivotal role in supporting people.

- Children and young people have missed out on education, developmental milestones, and important life-events.

- The pandemic has exacerbated existing inequalities, leading to higher rates of coronavirus infections and death amongst the most disadvantaged people.

Councils are best placed to identify people in their local areas who need the most support, and what support is required. This will require substantial backing from Government to bolster the recovery from the pandemic and ensure people are supported in the long term.

Councils continue to be financially hit by the crisis, with costs and losses of income likely to continue. It is difficult to predict the uncertain nature of how the pandemic, and its legacy, will impact local government. We welcome the funding Government has provided to date and call on Government to continue to monitor the situation both in the short and long term, providing vital support when needed. If the Coronavirus mutates again, and we are faced with a virus that escapes our current vaccine programme, it will be extremely important to be able to stand up all of the response infrastructure we have built, allowing councils to step in as they have done to protect our vulnerable communities, contain the virus, and keep our local economies going.

Efficiency

It is important to recognise that one of the goals of the Spending Review will be to set a new path towards sustainability of the public finances after the impact of COVID-19. This requires looking at how the public sector spends money, and on what priorities.

Councils have delivered more than their fair share of the burden of putting public finances on a more sustainable footing over the past decade and stand ready to help Government with the task ahead.

- Prior to the pandemic, councils had already dealt with a £15 billion real terms reduction to core government funding between 2010 and 2020. They responded to this by being more efficient, streamlining services and finding new and innovative ways of operating while still delivering the vital services their residents rely on and value.

- By way of example, there are now 626 shared services arrangements, with councils sharing the cost of a number of different services. These changes have achieved £1.3 billion of cumulative efficiency savings – money which is being used to protect the delivery of valued public services to local communities. Council planning departments have cut spending by 46 per cent in real terms. Despite this, councils have improved efficiency in making planning decisions, increasing the rate of decisions on planning applications received by 2 per cent since 2015/16.

- The traditional means of delivering efficiencies within local government have been exhausted. LGA work undertaken prior to the pandemic showed that the vast majority of remaining variation in spending between councils on older people’s adult social care and children’s services – the two biggest service areas – was explained by factors outside the control of councils (78 per cent and 71 per cent respectively).

- Despite the sustained pressure on council finances and the fact that local government is close to exhausting all efficiencies, residents’ trust in local government decision making remains high – nearly three quarters of residents trust their local council most to make decisions about how services are provided in their local area, compared to only 17 per cent who trust central government more.

Building back whilst stabilising public finances needs a completely different approach which unlocks the capabilities of local government to deliver savings across the public sector, instead of looking at local government budgets as just another budget line.

Councils are ready to help the Government deliver further significant efficiencies to the public purse through the following measures:

- A renewed focus on prevention, backed by government investment. A sure-fire way to address existing and future demand for services such as social care, homelessness support and community safety is to invest in lower cost approaches which help strengthen people, communities and local infrastructure. However, with council budgets stretched, a challenge of this scale needs to be kickstarted with government investment. Our submission provides a rich set of such investment opportunities.

- Reducing the fragmentation of government funding. Research commissioned for the LGA found that in 2017/18, nearly 250 different grants were provided to local government. Half of these grants were worth £10 million or less nationally. At the same time, these grants are highly specific – 82 per cent of the grants are intended for a specific service area. Around a third of the grants are awarded on a competitive basis and there is a cost to every application councils make, whether or not successful. All of these factors mean that if fragmentation and the ringfencing of grants is reduced, the system of local government funding can provide much better value for the same amount of funding.

- Bringing budgets together in a place. The approach to tackling fragmented funding can go much further, by looking beyond just local government funding. We need to allocate money to places and not departmental silos. A shared financial and governance framework will mean that services can better align with local priorities and local duplication of efforts can be eliminated. This Spending Review should place emphasis on communities and place by introducing multi-department place-based budgets, explicitly built around the needs of diverse local communities using equality impact assessments.

- Supporting councils to make local self-financed investments to help transform services leading to savings or generated income. This is covered immediately below.

Certainty

In addition to sufficiency in funding levels, certainty to enable councils to plan appropriately is just as important.

Councils have received one-year funding envelopes for three years in a row now and this is an obstacle to councils to making innovative and meaningful decisions over financial planning, so hampering their financial sustainability. Councils may end up planning on the assumption that they will have less funding available to them than is actually the case, needlessly scaling back non-statutory services and making redundancies.

Government must commit to councils receiving a three-year Spending Review settlement, including as much information as possible, such as council tax referendum limits (if any). The NHS, defence and schools have been benefitting from longer term certainty and the same should apply to council services which are vital to the national recovery, even if all other departments receive a one-year Spending Review outcome.

An early, three-year local government finance settlement should translate the Spending Review outcome into individual council settlements. In recent years, local government finance settlements have been published in draft form very late in December, after the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities’ stated target of 5 December. This target should be met.

The lack of certainty has been further exacerbated by the number of financial reforms which have been paused. Lack of information about whether and when these reforms will resume would mean that even if there was certainty over the overall total council funding sums for a number of years, this would not give individual councils the certainty they need for financial planning.

In this light, it would be extremely helpful to local government to receive confirmation of whether and when each of the planned local government finance reforms will be implemented as soon as possible. This includes the review of relative needs and resources (also called the Fair Funding Review), the business rates reset and the parameters of the new homes bonus.

Providing certainty on these issues would make a significant difference to council financial planning, and therefore public services, even without a Spending Review outcome. Councils could make decisions which provide better value for money for the taxpayer, by making longer term investments that deliver savings, if they had longer term certainty over funding. Of course, if or when financial reforms do go ahead, overall funding will need to be sufficient to facilitate them and to ensure no council sees its funding reduce.

Local taxation

Reforming council tax

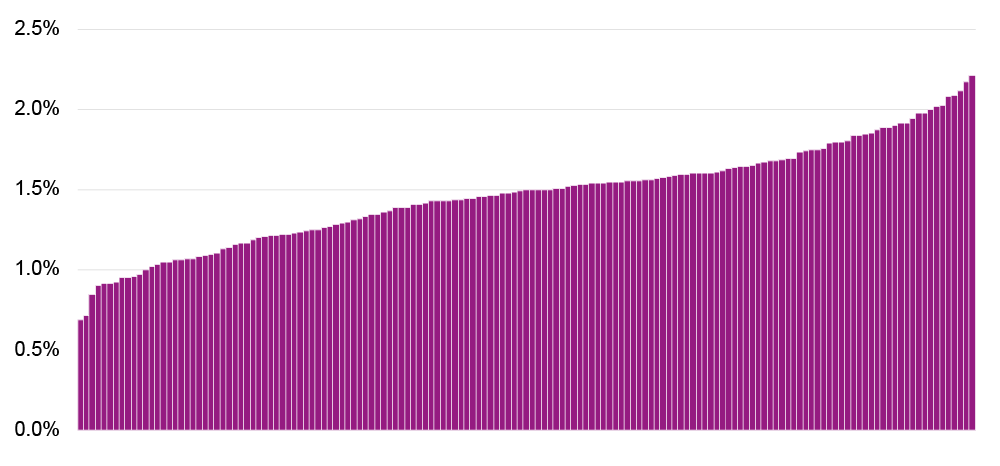

Council tax increases, including the adult social care precept, are not a long-term solution to funding services. Increasing council tax raises different amounts of money in different parts of the country. On its own, council tax falls short of the sustainable long-term funding that is needed to improve the services our communities and local economies will need to recover from the pandemic. However, that does not mean that council tax cannot be improved even without fundamental reform. We would like to work with Government to make council tax more local:

- To strengthen the accountability of councils to their residents through the local election process, the council tax referendum limit should be abolished so councils and their communities can decide what increase in council tax is warranted to protect or improve local services. Ending referendum principles would also improve value for money – a referendum costing potentially up to £1 million would have to be organised to approve a council tax bill increase of as little as £1.15 per week. Failing that, the Government should consider ways to define the referendum limit which do not reward or penalise councils based on their past decisions. For example, the percentage-based limit could be replaced by a threshold which allows higher percentage increases to areas with lower council tax levels, similar to the £5 flexibility provided to shire district councils. In addition, the council tax levy paid to drainage boards should not be counted towards the cap on council tax rises. Any additional costs should not fall on council taxpayers.

- To make sure the tax system is fair to everyone according to local circumstances, councils should have the powers to vary all council tax discounts and eligibility criteria. Most discounts and exemptions are fixed nationally. A prime example is the single person discount, worth 25 per cent of the total bill and applied to all households where there is only one liable occupant, regardless of their ability to pay. This discount is currently worth £3 billion each year, covering around a third of all dwellings.

- To improve the build-out rates of homes with planning permission and reduce the number of stalled sites, councils should be able to charge developers or landowners full Band D council tax for every unbuilt development in these situations, as opposed to having to wait for the Valuation Office Agency (VOA) to list developments following their completion. LGA analysis suggests that over one million homes granted planning permission since 2010 have not yet been built. This is equivalent to three years’ worth of Government’s target number of homes to be delivered each year.

- As COVID-19 support measures, like the furlough scheme, end from September 2021 the local Council Tax Support (CTS) Covid Grant should be continued for the three years of the 2021 Spending Review, linked to changes in the number of predicted working age claimants, so councils can continue to help the most vulnerable council taxpayers.

- We would like to work with the Government to improve the generational fairness of local CTS by revisiting the pensioner element of local CTS to give councils more flexibility. However, this should not be accompanied by further reductions in government funding for CTS to avoid the experience of the 2010s.

Reforming business rates

As part of the Government’s Business Rates Review, the Government has acknowledged that business rates are an important source of revenue for local government and stated that the impact on the local government funding system will be an important consideration in reviewing the tax.

Property continues to provide a good basis for a local tax on business. Business rates are efficient to collect and have been relatively predictable and buoyant in recent years. However, the changing nature of business alongside the nature of demand pressures on councils means that we cannot look to business rates to form such a substantial part of local government funding in the future and alternative means of funding councils will be needed instead of, or as well as, a reformed business rates system.

Our proposals for reforming business rates include the following:

- If local authorities had more leeway on business rates relief, they would be able to help local and independent businesses in order to stimulate the local economy. This could be done by making large national reliefs, such as charitable and empty property relief, discretionary. It would also allow councils to incentivise other behaviours that match local and national economic priorities, for example providing reliefs for new or green investments.

- Many fundamental concepts have been set by case law and not by statute, leading to results which may seem puzzling to the public, such as the fact that large vacant sites may not pay business rates. Changes in the basis of liability are needed so that more is defined in statute.

- The complex framework of business rates exemptions needs to be reviewed. This includes, for example, agricultural exemptions where there are businesses which should normally be rated but just happen to be located on farms.

- Aggressive business rates avoidance continues to cost councils and central government more than £250 million each year. We call for the Government to tighten up on the abuse of reliefs along the same lines as have been introduced in Wales and Scotland.

- We will be replying to the consultation on more frequent revaluations which proposes a compliance regime for ratepayers at the same time as the move to three yearly revaluations. We consider that a similar compliance regime should apply to ratepayers in their dealings with local authorities.

- Local government should be able to set its own business rates multiplier, or at the very least be able to set a multiplier above and below the nationally set multiplier. Local authorities ought to have the power to vary multipliers by property value or property type. This would enable them, for example, to charge a higher multiplier to businesses, such as online warehouses, in order to support reliefs for other businesses.

Alternative and new sources of funding

The Government’s fundamental business rates review, which considers both reforms and alternatives to the tax, is an important opportunity to take a fresh look at the local government finance system as it is being stress-tested by the impact of the pandemic.

For example:

- The recent announcement of a health and social care levy follows our long-standing calls on the Government to make the case for national taxation increases, or new levies, to fund adult social care pressures. The announcements are covered in more detail in the next chapter.

- Taxation should be fair for both physical and online businesses. We welcome the fact that the Government is consulting on proposals for an online levy as part of the review, however the proceeds of such a levy should be retained by local government to diversify the local taxbase. We look forward to action on this when the review reports.

Overall, local government needs a funding system that raises sufficient resources for local priorities in a way that is fair for residents and gives local politicians the tools they need to be the leaders of their communities. It is therefore important that the tax system provides as much certainty as possible.

In the meantime, we are calling on the Government to publish a progress update on the review as part of Spending Review announcements.

Capital investment framework

Investing in infrastructure with capital spending will be crucial to delivering the social and economic recovery from the pandemic, delivering key government priorities on net zero, housing and regeneration, and making the public sector more efficient and able to deliver better value for money while providing key services for citizens.

Councils are best placed to deliver capital infrastructure to enable economic regeneration, housing and school improvements, service transformation and to support Government’s move towards net zero carbon emissions, if they are given the right financial freedoms, flexibilities and support.

The Government has recently published its ‘planned improvements’ for the local authority capital framework. We welcome the undertaking that any significant changes to the capital regime will be subject to individual consultations, and as yet the full detail of what the changes are and what they will mean is not yet clear. However, we will continue to make the case that any changes need to be proportionate and that the overall framework for capital finance should continue to allow local authorities wide freedoms to borrow and invest, without the need to seek prior approval from government, if councils are to be able to play their key role in delivering capital infrastructure.

Our submission contains many examples of where councils can play a key role in delivering priorities, such as fixing the nation’s roads and delivering economic regeneration, delivering high speed broadband and high-quality mobile connectivity everywhere, investment in housing (coupled with reform of Right to Buy), schools, transport infrastructure, as well as tackling environmental challenges including reforms to waste and recycling and carbon reduction.

Government grant funding of council capital programmes has reduced in recent years. Capital funding in 2019/20, the last year for which outturn figures were published, was £300 million lower than in 2014/15. If 2014/15 levels of grant had been maintained in the intervening years councils would have had an additional £2.3 billion to invest in local capital projects between 2014/15 and 2019/20. Such funding could help shore up local infrastructure – for example it could reduce the highways repairs backlog by a fifth, be used for local housing and regeneration, or put towards the provision of additional school places.

Where government capital grant funding is available, it is frequently fragmented and accompanied by bureaucratic and burdensome bidding processes. For example, there are at least 11 different capital funding streams for roads investment alone, each with their own arrangements, rules and allocation processes. Councils have frequently had to consider the risk of investing significant time and revenue resources that cannot be spared into long-winded processes that are not guaranteed to deliver any local benefits.

A further funding freedom can be delivered very simply, and at no cost, by making the flexible use of capital receipts arrangements permanent and available to fund all transformational and savings projects. Government first introduced this flexibility in 2015 and although extension of the scheme beyond 2022 was announced in the 2021 Budget, details of how the scheme will operate have not yet been confirmed. The Spending Review is the opportunity to make this permanent, adding certainty and removing the need for further review.

Priority 3 - Investing communities and tackling health inequalities

As the Prime Minister and the new Secretary of State for Health and Social Care have recently highlighted, there are serious inequalities when it comes to health and life chances across England which affect, among other things, the economy in a reciprocal relationship. Local government is a key delivery partner in addressing these inequalities and enabling levelling up across the country. We have heard from different areas about the unique challenges they face. It is clear that the concept of levelling up is multi-faceted and will require investment in social as well as physical infrastructure and it is vital for central and local government to work together on these multiple issues, in a unique mix in each local area, at the same time.

As we have argued above, trying to manage multiple priorities at the same time has in the past led to a sprawling number of central government funding streams, all with their unique conditions, reporting requirements and distribution methods. This poses a serious risk of duplication and failure to achieve value for money, but also requires significant resource from an already depleted workforce. Indeed, addressing the multitude of priorities and issues we cover throughout this submission individually would contribute to fragmentation of funding even further.

We recognise that, in the current public finance context and with the need to achieve long term sustainability in our public spending commitments, it is unlikely that government will be able to fund all the preventative and early intervention proposals that we have put forward in the past as set out in table 3. However, we will not be able to level up communities if we do not make a start.

| Proposal | Sum, annual |

|---|---|

| Investing in adult social care prevention, innovation and equality of outcomes | £1 billion |

| A public health prevention transformation fund | £2 billion |

| Investing in early intervention in children's services | £1.7 billion |

| Total | £4.7 billion |

Our solution, therefore, is to start smaller and build community infrastructure over time in a way that allows local areas to target funding to their greatest local priorities.

The Spending Review is an opportunity to put a fresh and innovative approach into action by introducing an unringfenced and ongoing Community Investment Fund, worth £1 billion in 2022/23 and increasing to £3 billion by 2024/25, so that councils can invest in supporting individuals and strengthening communities according to priorities in their local areas.

This unringfenced fund could have a requirement that councils are clear with residents which schemes and initiatives are financed by the fund, similarly to how the source of funding for infrastructure spending has been advertised in the past. It is likely that much of the funding would be directed through the voluntary and community sector, though councils might directly deliver or look to local businesses to address some requirements. This could also build in local social value benefits.

Councils would be empowered to use this funding to start building back resilient communities and tackling health and social inequalities, for example by investing in the following areas:

Adult social care prevention and innovation

New and dedicated funding for each year of the Spending Review period could enable increased spend on prevention and innovation to help prevent or reduce the need for longer-term support. Local priorities might include:

- Enabling increased investment in preventative services including those provided by the voluntary sector to support people in their own homes and keep them engaged in their communities to avoid escalating need and more formal health and social care interventions. This would include supporting informal carers.

- Funding support for action on adult social care inequalities. The disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on some communities has exposed long endured patterns of inequality and discrimination. The proposed funding would allow councils to begin targeting specific action to address inequalities and poor outcomes for those people at greater risk.

- Investing in innovation and technologies to enhance outcomes. This could include assistive technology, predictive analytics and apps. This would also support bringing evidence-based but currently marginalised positive models of care and support into more mainstream use and could also be used to develop and rapidly test solutions to particularly challenging care problems.

As set out in the NHS plan and aspired to in the Care Act, a preventative model, rooted in local communities, would be better for people, reduce rising demand for social care over time and better for the NHS by preventing or delaying an individual’s attendance at hospital – making a saving to the public purse.

Public health

Public health services are vital to tackling the health inequalities which are preventing us from levelling up the country. With greater, more consistent funding for councils’ public health services, alongside other local government services such as housing, sport and leisure provision and employment, councils can influence the future health management and life chances of our communities.

Councils would have the option to use the Community Investment Fund to supplement spending from the public health grant so that they can offer a wider public health programme targeting particular local challenges. Our previous work shows that scaling up good practice examples from across England could be highly cost-effective, delivering a return of 90 per cent to the public purse through savings on services across the public sector.

Early intervention in children’s services

The Independent Review of Children’s Social Care has identified that ‘It is getting harder to meet children’s needs within the current system and if we don’t take urgent action to prevent this, costs will continue to rise and the situation of children will deteriorate. There is no situation in the current system where we will not need to spend more’.

Councils would have the option to use the Community Investment Fund to invest in the early intervention support that their local children and families need, so that we can make sure help is available when it’s first needed – not later down the line when the situation has reached crisis point. Councils could target funding according to local priorities which might range from early years support to families to crime prevention activity focused on young people.

The Case for Change published by the Independent Review of Children’s Social Care highlights a range of evidence on the impact of investment in preventative services, including:

- reduced spending on preventative and family services is associated with rising rates of adolescents entering care

- an additional 8,750 to 24,400 children in need than would have been expected had spending on preventative and family services remained at 2010/11 levels

- spend on early help is associated with better Ofsted inspection outcomes.

There is also clear evidence on the benefits of specific programmes of prevention and early help, for example:

- the Troubled Families programme reduced the proportion of children in care and reduced juvenile custodial sentences and convictions

- greater coverage of Sure Start centres led to a fall in hospitalisations of children up to the age of 11, saving the NHS £5 million per cohort of children

- reducing the attainment gap between disadvantaged pupils and their peers across the country to the same size as in London would deliver an overall economic benefit of around £12 billion over the lifetimes of those young people.

Local flexibility is key, allowing councils to meet the needs of local families and effectively integrating with existing provision in a place-based approach to prevention and universal support.

Mental health

Supporting people’s mental health and wellbeing underpins all aspects of the COVID-19 recovery. From reopening schools, to getting the country safely back to work, dealing with the economic and housing consequences of the pandemic, and supporting people who may have become lonely or socially isolated. The Centre for Mental Health estimates that 10 million people, including 1.5 million children and young people, will need support for their mental health as a direct result of the pandemic over the next three to five years with some population groups at higher risk than others.

The annual cost of mental health problems in England is estimated to be £119 billion, measured in terms of spending on health and the impacts on an individual’s work or education. Mental health problems cost UK employers £35 billion a year in sickness absence, reduced productivity and staff turnover. Three-quarters of mental health problems first emerge before the age of 25, so it makes sense economically to invest in mental health support for young people, as well as making a huge difference to people’s lives.

Improving people’s mental health has the potential to help public finances as well. Evidence-based parenting programmes, for example, are estimated to generate savings in public expenditure of nearly £3 for every pound spent over seven years, with the value of savings increasing significantly longer term.

Community learning

There are other purposes for which the Community Investment Fund could be used, for example, realising the wider social and health benefits associated with councils’ community learning activity (currently funded through the Adult Education Budget) to engage those that most need support to start or restart their journey back into employment and which also helps reduce loneliness and ill health, improves social integration and active citizenship. This is however closely connected to current reforms to adult education funding through a new Skills Fund which must not lose the wide-ranging benefits of community learning. Any use of the Community Investment Fund for this purpose would have to be additional to, as a minimum, local government continuing to receive receiving at least £220 million through the new Skills Fund for delivery of community learning within an enhanced and adequately funded council-run adult and community education service.

Priority 4 - Reaching net zero

The Government has legislated to reduce carbon emissions by 78 per cent by 2035, and to reach net zero by 2050. To achieve these goals, Government will need to build effective partnerships to broker deals across a range of sectors.

Locally, councils have existing relationships with a whole host of partners which they can use to help deliver the individual changes needed to meet the national target. The majority of councils have declared a climate emergency and already areas such as Yorkshire and Humber and Hertfordshire have climate change partnerships involving their local NHS bodies and other major partners to look at how they can collectively meet emissions’ targets.

Councils have also supported the electric vehicle industry by investing in on and off-street electric vehicle (EV) charging infrastructure – contributing to the 21,000 public charge-points across the UK. Birmingham City Council has brought the first Clean Air Zone into operation which by 2026, is estimated to reduce the number of asthmatic children showing bronchitis symptoms by 873 a year. It will also contribute towards Birmingham’s commitment to a 60 per cent reduction in carbon emissions by 2027. Given that it is the single largest source of emissions in this country, transport has a significant role to play in helping the country to reach its net zero targets.

To deliver significant progress on net zero it is going to be necessary to ask the public to make further behavioural changes. The public have already made some of the easier changes, such as swapping to reusable shopping bags/water bottles and getting better at recycling. But the next phase of behavioural change is going to need more commitment from the public as we look to swap our modes of transport and seriously review our own personal consumption. The Committee on Climate Change estimates that future reductions in emissions will rely on as much as 62 per cent of our individual choices and behaviours.

Although there are significant challenges ahead there are also many opportunities for national and local government to work together. Councils will work as partners with Government to tackle climate change, using their place-shaping role and drawing on their longstanding ability to collaborate and build cohesion with local partners and residents. Community capacity and cohesion issues will arise in the transition to net zero and it is only at the local level that these can be addressed.

If the UK is to remain a leading global example, Government needs to unlock councils’ full potential. It is clear that the transition to a net-zero carbon society will require substantial additional public and private financial resources.

The Government should work with councils and businesses to establish a national fiscal and policy framework for addressing the climate emergency.

This framework should outline responsibilities for the Government nationally – for example, aligning the regulatory system, including the planning system and national tax incentives – and the local responsibilities, together with a commitment to cooperate with local public sector bodies. There should be a process of engagement between central and local government and industry to enable councils to fulfil their role to translate a national framework into transformative local plans that deliver on this agenda and invest in solutions for a green recovery and future.

The framework must be underpinned by a long-term revenue and capital package to address climate change and meet the net zero target. Local government can work with central government to help identify the costs and how they can be funded.

Alongside the framework we need to pilot place-based approaches that will help us speed up the pace of action and achieve economies of scale. We need to be bold and let local areas lead the green recovery and give them to opportunity to test radical new approaches, such as devolving skills and powers funding and responsibilities to speed up the green recovery. This could include further funding for specific village, town and city wide pilots on EV charging coverage, local energy schemes and other initiatives.

Decarbonising housing

Decarbonising existing council housing will require significant investment. Analysis undertaken by Savills for the LGA before the pandemic (available on request) estimated that the additional investment costs to achieve net zero carbon in existing housing stock held within councils’ Housing Revenue Accounts (HRA) is almost £1 billion per year over a 30-year pattern of investment. This will have an impact on other council housing programmes and the ability to deliver statutory functions.

There is an opportunity, through decarbonising both our existing housing stock and new build homes, to help economic recovery whilst achieving the shared local and national government’s net zero target. Targeted policies can support both the construction sector and low-carbon and job creation in deprived areas, including those most impacted by the pandemic thus also supporting the Government’s levelling up agenda.

Giving councils the tools, powers, flexibilities and resources that they need to decarbonise heat in homes, including bringing forward the £3.8 billion capital Social Housing Decarbonisation Fund will help the rollout of an ambitious national retrofit programme across all tenures that will create jobs, support local economies, cut fuel bills, and help tackle fuel poverty.

Transport decarbonisation and Local Transport Plans

Councils have much to do over the coming years to work with Government to deliver the Transport Decarbonisation Plan and the local schemes that will be needed to move away from carbon dependent travel. Councils will be looking to:

- prepare Local Transport Plans that deliver against quantifiable local carbon reduction targets

- consolidate their work and prepare a pipeline of cycling, walking and bus prioritisation schemes along with other transport initiatives to meet local transport priorities, as well as national targets, such as 50 per cent of all urban journeys to be cycled or walked by 2030

- respond to demand for electric and zero-emission vehicles, with a focus on provision for charge points for those without off-street parking

- respond to future transport trends – such as the roll out of escooter rental schemes and regulation of private escooter ownership and ‘last mile’ freight/delivery consolidation schemes

- further integrate transport and spatial plans.

In order to undertake these activities and be effective partners of Government councils will require additional resources to invest in capacity and expertise to develop plans and ensure quality and value-for-money scheme delivery.

Funding each highways authority with an additional £2.1 million revenue support for the remainder of this Parliament and committing an additional £700,000 each year for the next Parliament will help ensure councils are able to co-deliver the Government’s ambitious Transport Decarbonisation Plan.

This additional amount will help by ensuring every highways and transport authority has the minimum resources they need to plan, consult, design, promote and deliver their local schemes in contribution to the national Transport Decarbonisation Plan. It will also consolidate any existing revenue funding, such as for producing Bus Improvement Plans.

Waste and recycling

Councils have a strong track record in reducing the amount of waste sent to landfill and using technology to make services more efficient and reduce road journeys by collection teams. Household collection services are a very visible part of the recycling process but change needs to happen across the whole chain of actors, from retailers right through to the recycling industry.

We welcome the introduction of extended producer responsibility (EPR) and new legislation that will require manufacturers and retailers of packaging to pay councils the full cost of material that ends up as household waste and litter. This must include the costs associated with increasing recycling rates. EPR revenue should flow in its entirety to local government.

We do not support the Government’s conclusions on the economic and environmental benefits of free garden waste collections. The evidence to support the free collection of garden waste is not compelling and does not take into account the opportunities to increase home composting, the provision of free disposal at household waste and recycling centres, the emissions implications of increased vehicle movements and the fact that a large proportion of urban properties do not have gardens, this proposal is unfair and unnecessary. The majority of councils have declared a climate emergency, and policy approaches that increase the number of fossil fuel-consuming vehicles driving up and down our roads is counterproductive. Free garden waste collection would have an initial cost of £176 million to implement and an annual running cost of £564 million. This would need to be funded should the Government go ahead.

Priority 6 - Building back local economies

Economic growth and recovery funding

Throughout the response to COVID-19, councils have demonstrated their value as leaders of place, utilising their local knowledge and leadership to deliver the most appropriate solutions for their areas and communities. Councils understand the need for locally responsive actions to promote sustainable and inclusive economic growth and recovery but need the right powers and resources to be able to make a meaningful change in their places.

This is all the more important because the impact of the pandemic has been felt acutely, but differently, by all types of areas across England. For example:

- In urban areas, the pandemic has both amplified existing challenges and created new ones. Urban areas remain vulnerable to further economic changes such as poor productivity growth, poor earnings growth, inequalities, and housing need. Cambridge Econometrics forecasts a loss of half a million jobs in urban areas between 2019 and 2021 in manufacturing, finance and insurance, hospitality and leisure, retail and other services. There have been proposals for dedicated recovery funding for urban areas, such as the Sustainable Urban Futures Fund.

- Rural places’ economic reliance on small businesses (including a high proportion of micro-enterprises with under ten employees) and on sectors such as tourism and hospitality have left them exposed. Rural and coastal economies were among the slowest to recover after the last recession. A range of proposals have been made to strengthen economic resilience in these areas including: more investment in digital connectivity; better targeting of growth funding to address pockets of deprivation; and better business support for micro-businesses, including extending the ‘Help to Grow’ scheme to those with fewer than five employees.

In order to build on the excellent work of councils throughout the pandemic and to build on the momentum for transformation, councils need access to funding which is long-term and transformative in scale. As well as ‘hard’ infrastructure funding, we need investment in social infrastructure, including the voluntary, community and social enterprise sector, to support community resilience and recovery – for example through the Community Investment Fund we outlined in priority three.

Fragmented, short-term and competitively funded pots will limit the ability of councils to create integrated initiatives for recovery and growth, to work at scale and to create sustainable change in their place. Growth funding must not simply recycle existing funds under a different name, but should be of a meaningful scale and term to address different local needs across the country.

In light of the unprecedented challenge facing the country, we propose that at a minimum this should match the £9.1 billion of Local Growth Funding awarded between 2016 and 2021.

Digital connectivity

During the pandemic, access to effective broadband services and mobile internet have been essential to facilitate working and learning from home. However, 17 per cent of rural residential premises and 30 per cent of rural commercial premises still do not have access to superfast broadband (30 Mbit/s or higher). This needs to change if rural England is expected to seize the benefits of home working and attract high tech, high value businesses.

- Investment in broadband services should be prioritised for those with the least connectivity first, and a £250 million contingency fund should be created for councils to support the rollout of ultrafast broadband in those areas that fall within the scope of Project Gigabit, but which are lagging behind delivery.

- The cost cap of £3,400 for the Universal Service Obligation should also be reviewed, with a view to better understand the extent of premises with costs above the cap, and a mechanism for funding those excess costs identified.

- Government should provide £30 million a year for councils to put in place a local digital champion to help coordinate delivery locally and to recruit extra capacity within highways and planning teams to respond to surges in local roll out activity, such as streetworks permit requests or planning applications.

UK Shared Prosperity Fund

The Government has recognised local government as place leaders and natural partners of national government by confirming them in a lead role in the Community Renewal Fund (CRF), the pilot for the Shared Prosperity Fund (SPF). With the right resources and freedoms and building on the learning from the CRF, councils are in a prime position to support the delivery of central government’s ambitions of levelling up, tackling inequalities and building back better.

The introduction of the CRF has enabled local government to demonstrate their role as place leaders, bringing together strategic direction, local intelligence and expertise in economic development and inward investment, stakeholder engagement and democratic accountability. The SPF’s design can take this a step further by providing a fund that is flexible and will deliver the place ambition of local government and the needs of our communities and economies.

- There are numerous funding streams, both new and old, helping to deliver national government’s levelling up agenda, with some streams funding very similar activity. New funds such as the Levelling Up Fund, the High Streets Fund and Freeports, are all operating different processes. The then-MHCLG Secretary of State’s commitment at this year’s LGA Annual Conference to reduce the number of funding streams is positive. The SPF could be a catalyst to bring these funds into a single programme and make a real impact to local communities driven by local need. It could help local government to simplify funding allocation processes, limit the duplication and bureaucracy of multiple bidding processes and free up time and resources to encourage innovation.

- There is an opportunity to learn from the CRF process and develop a more effective, streamlined national framework for the SPF programme that allows for national government accountability as well as local determination of outcomes. Such a framework should be developed with local government to reflect this partnership and ensure that it as effective as possible.

- The SPF should encourage innovative and localised solutions to tackling inequalities. This can only be achieved if it is fully resourced by being at least equal to the quantum of the funding streams it is replacing, including £5.3 billion in previous structural funding and all other predecessor funds. It should be distributed over a longer term, stable period to deliver the benefits to local economies and communities.

Employment and skills

Since the pandemic hit, councils have led from the front, used their knowledge, links and leadership and been trusted to bring together partners to support residents and businesses. The Government’s ‘Plan for Jobs’ rightly introduced vital new support to help learners, jobseekers, and businesses, but it added to an already confusing national employment and skills system.

With more chance to co-design support with Government, councils could enhance the national offer. For instance, we set out our views on how Kickstart should be developed including what incentives and support employers should be offered to keep a young person on through a traineeship, Kickstart placement and then on to an apprenticeship. Similar opportunities to create a more rounded offer for unemployed people by building in local support (housing, mental health, financial, skills) to the national Restart offer, are possible if the programme is reshaped.

To deliver jobs and growth, especially as furlough comes to an end and we move towards the next stages of economic recovery, national and local government must combine resources and expertise.

To make this happen, the Government should:

- Co-design with councils new, or repurpose existing support, contained in the Plans for Jobs and Growth and trust them to coordinate provision across their areas. To complement the lead council role in determining local infrastructure spend to create new jobs (Levelling Up, Community Renewal and Towns Funds) and shortly the SPF, they should also now be trusted to have a lead role in coordinating employability support and work in partnership with Government to reshape existing support (Kickstart, Restart) and other programmes. Connecting infrastructure and employability spend in this way will help local people benefit from these new opportunities, level up places across the country and allow councils to deliver a clear local offer to young people.

- Build local green jobs into its national strategy. LGA research shows that up to 1.1 million green jobs across England could be required by 2050. As the Government has now published the findings of its national Green Jobs Taskforce, we have a real opportunity to join up the dots in policy and funding decisions.

- Extend the current Apprenticeship Levy incentive (due to expire in September 2021) to March 2022 so councils and other employers can support even more people into training and work. The two-year expiry date for levy funds should also be extended where employers have been unable to use it due to the restrictions brought on by the pandemic. More fundamentally we urge the Government to deliver a root and branch reform of the Apprenticeship Levy. This should include giving councils maximum local freedom and flexibility to use these funds such as the ability to pool levy funds to better plan provision across their areas to address supply/demand side issues, target sectors to support the local business community, and widen participation to disadvantaged groups and specific cohorts, and use a proportion of the levy to subsidise apprentices’ wages and administration costs.

- Extend and repurpose Kickstart. Despite limited national data, councils have been instrumental in getting Kickstart off the ground, creating placements within their own workforces and supporting local businesses to do the same, including through much-valued gateway models. The Government should extend Kickstart beyond its December 2021 cut off point, open up referrals to those not in receipt of Universal Credit, 16 and 17 years olds as well as adults, and enable councils to plan provision.

- Restore adult skills funding to its 2010 levels (from £1.5 to £3 billion) and fully devolve it to expand training opportunities. A consultation on a new Skills Fund replacing the current Adult Education Budget should provide more chances to increase skills levels from community and entry level to higher levels to help adults enter and progress in work and cement local government’s adult education functions within the wider skills landscape. The current Adult Education Budget includes £220 million for community learning which supports vital community based and outreach activity for councils to engage those adults most in need of support to progress into learning or employment, but brings with it much wider social and community benefits which must not be lost in the Skills Fund reforms. We urge the Government to recognise this. Alongside this, National Careers Service contracts, due to expire in 2022, should be localised and devolved where possible.

Looking ahead, councils need to be empowered to work innovatively with their communities, the Government and its agencies to design a locally determined skills and employment offer in exchange for sustained outcomes for their residents and businesses. The LGA has a framework for this to happen. Now is the time to put Work Local into action. The Government should use it to back and fund pathfinders across rural, coastal and metropolitan areas and deepen existing devolution deals.

For a medium-sized combined authority each year, our Work Local model could lead to an additional 8,500 people leaving benefits and 5,700 people increasing their qualification levels, with additional local fiscal benefits of £280 million per year and £420 million to the economy.

Highways and public transport

Buses and public transport

Buses are the cornerstone of the Government’s future plans to decarbonise the way we travel, as set out in the Transport Decarbonisation Plan and also in the National Bus Strategy.

However, they have suffered a major collapse in passenger numbers and revenue due to the pandemic. Bus ridership is recovering slowly but has still not reached 75 per cent (in London) or 70 per cent (outside London) of pre-COVID levels. Emergency Government support and support from councils has protected most services and over the coming year the £226 million recovery funding from the Government will help.

In order to allow councils to revolutionise local bus provision so that people are able to access jobs, learning opportunities, meet people and access vital services in a more sustainable and cheaper way, the Spending Review needs to:

- make good the £700 million funding gap on concessionary bus fares

- commit to devolving the Bus Services Operators Grant to all councils that request it as set out in the National Bus Strategy

- monitor and review the adequacy of the £226 million Bus Recovery Fund, available until the end of 2021/22, in addressing any ongoing reduction in passenger revenues in local public transport and buses.

Highways maintenance

In recent years the Government has been a strong supporter of local roads maintenance, recognising the importance of resilient and well-maintained highways infrastructure to all road users and business and each Parliament has seen an increase in funding to councils.

It was therefore surprising and disappointing that the 2020 Spending Review effectively reduced the amount available to councils. The LGA estimates the reduction in total highways maintenance funding at just under £400 million from the total amount allocated for 2020/21 – a reduction of 22 per cent from the previous year.

In order to tackle the £10 billion backlog of road repairs, the Government should reinstate its commitment to provide an additional £500 million per year for road repairs on top of the baseline amount of £1.3 billion provided in 2020/21, bringing a total of £1.8 billion per year.

The cost of construction has also increased significantly, reflecting global supply problems. Future capital allocations should take into account the significant inflation rates in highways construction and maintenance costs.

Long-term capital funding certainty

Both Network Rail and Highways England are planning their investment strategies for 2025-2030, developing pipelines of projects with agreement built upon multiple previous five-year funding agreements. These investment strategies are explicitly to support planning and delivery capacity and enable flexibility in spending decisions. More recently, eight mayoral combined authority areas are also set to benefit from £4.2 billion of government investment in five-year funding settlements for local transport starting in 2022/23, and £50 million in 2021/22, to support preparations for settlements.

Long-term certainty of funding also delivers efficiencies and better value for money for tax-payers and is more attractive to third party investors. All local infrastructure and transport should be benefitting from the same five years’ funding certainty that Network Rail, Highways England and mayoral combined authority areas currently receive. This should be the nature of all infrastructure funding for all areas and councils are pleased that the Transport Decarbonisation Plan recognises this.

Future infrastructure funding should also move away from competitive funding. Funding in this way means councils are spending money on pulling together bids without certainty of success, is short term in nature and removes decisions away from things that matter to local people.

Delivering housing that is affordable for all

Local government shares the Government’s ambition of delivering 300,000 new homes a year. Investment in new housing supply of all tenures will play a vital role in rebuilding the national economy following the pandemic. New homes have delivered almost £148 billion of construction output since 2018, of which 16 per cent was delivered by the public sector.

A key part of delivering a recovery for all is more quality homes in the right locations and the supporting infrastructure to create sustainable, resilient places. This includes building more homes for social rent. This will help local and national government collectively to address the national housing shortage and reduce rising levels of homelessness.

We want to work with government to secure funding for a council housing stimulus package which would support the delivery of 100,000 new homes for social rent each year – providing secure, stable, affordable homes for residents as well as delivering long-term fiscal benefits.

Building 100,000 homes would:

- Improve the public finances over thirty years by £24.5 billion according to LGA analysis.

- Make a major contribution to the shared ambition of 300,000 new homes per year.

- Offer a pathway out of expensive and insecure private renting towards ownership.

- Reduce the housing benefit bill, thus reducing the cost to Government of meeting the housing needs of those on a low-income.

- Support the rapid scaling up of sustainable supply chains that is needed if we are to achieve net zero by 2050. For example, it has the potential to support a standardised programme of training for plumbers and electricians in fitting air source heat pumps and/or other technology.

Building on recent important changes to Right to Buy introduced in March 2021, the Spending Review is a chance for the Government to go further and faster in providing local government with a broader range of flexibilities to be able to support it in its housebuilding ambitions, such as:

- Bringing forward further Right to Buy flexibilities, such as allowing councils to set discounts locally, combine receipts with government grant funding (such as the Affordable Homes Programme) and transfer receipts to ALMOs and/or housing companies to give greater flexibility as to how new council housing is delivered.

- Allowing the value of land released by councils’ general fund to be assessed as part of the cost for Right to Buy 1-4-1 calculations in the same way as if it was bought on the open market. This would incentivise the use of council land for affordable housing.

- Launching a Right to Buy pilot programme that allows councils to retain 100 per cent of receipts from the sale of homes with no restrictions on their use.

- Committing to monitoring the impact of the cap on the use of Right to Buy receipts for acquisitions being introduced in 2022 and revising the policy if it is found to be restricting overall housing delivery.

- Rapidly scaling up Homes England’s strategic partnerships with local authorities, so that rather than applying for funding on a scheme-by-scheme basis, local authorities can enter into multi-year grant agreements to deliver affordable housing.

- Working with local government to secure additional capacity and improvement support for housing delivery teams within councils and their delivery partners. This should ensure that there is a suitable and sufficient mix of professions able to deliver housing projects for councils.

- Setting a long-term rent deal for council landlords to allow a longer period of annual rent increases for a minimum period of at least ten years. This should include some flexibility for councils to address the historic anomalies in their rents as a result of the ending of the ‘convergence’ policy.