Introduction

Voluntary and Community Sectors (VCS) organisations offer huge amounts to local areas, through the services they provide, the wealth they generate, and the people they connect, engage and empower. At a time of rising pressure on services and tough financial constraints, it is more important than ever that councils can harness their local strengths and build successful partnerships with their local VCS.

This toolkit aims to support councils on this journey. It builds upon research commissioned by the Local Government Association and conducted by Locality, into the state of strategic relationships between councils and their local voluntary and community sector. This in-depth work explores the different types of strategic relationship, the principles underpinning them, the benefits they bring, and the barriers to achieving them.

This toolkit is designed to help senior officers and lead members put the research findings into practice. By using this toolkit councils can:

- Deepen their understanding of the benefits of effective partnership working with the VCS.

- Assess the current state of their strategic relationships, where there are strengths and weaknesses.

- Agree concrete steps to further strengthen their relationships.

What’s the current state of strategic relationships?

Locality’s research found the state of strategic relationships between councils and the VCS can be summarised in one word: mixed. Some councils engage clearly and consistently across departments, some have effective relationships in pockets or that sit with individuals, while others have little engagement at all.

There are a number of common barriers to effective strategic relationships. These include: perceived or real differences in priorities and approaches between councils and the VCS; a lack of capacity to proactively invest in relationships; and long-standing issues around existing relationships and structures.

The aim of this toolkit is to help councils overcome these barriers, should they exist. All councils will be starting from different places, so this toolkit can be used to understand the state of your council’s strategic relationships and take clear and practical steps to strengthen them from any starting point.

Throughout, the toolkit provides short real world examples to showcase what good looks like and demonstrate the art of the possible. In these exemplar areas, councils and local VCS organisations are achieving huge things together. They illustrate what can be achieved when people come together in the spirit of partnership to tackle common challenges. More detailed case studies can be found in the research report 'The state of strategic relationships between councils and their local voluntary and community sector'.

Self-assessment tool

This toolkit brings together three core elements of Locality’s research to provide a practical self-assessment tool:

- the benefits of partnership working with the VCS

- the main types of relationships between councils and the VCS

- the principles for successful relationships.

The aim of this is to help councils to understand the strengths of their own strategic relationships, identify weaknesses, and plan ways forward.

This is not an exercise councils can do on their own. Shared foundations are a crucial building block of effective council/VCS relationships. While it may be worth doing some initial work internally to build understanding and buy-in, it is important that councils don’t just come to their own view on what local relationships look like without proper engagement and involvement from local partners.

The toolkit uses three main areas of self-assessment. Each involves a series of questions as a prompt for discussion, as a means of deepening understanding and developing actions to improve current working. This exercise will be more effective by including a range of perspectives and so we recommend involving colleagues from across various council departments.

Different types of councils will need to approach this exercise in different ways. Two-tier areas, for example, will need to consider when and how to involve county or district colleagues. Other areas may want to think about how to incorporate relationships held by parish councils or combined authorities. In a similar way to involving the VCS, the assessment could usefully be done to aid internal discussion by one tier in isolation, but probably only as a starting point and whole area collaboration will be required to develop a comprehensive picture.

None of this is an exact science. The central aim of the self-assessment tool is to provoke conversations internally and externally about the state of strategic relationships in an area, how they might be improved, and, crucially, what could be achieved if they were.

It’s important to highlight that not all relationships need to be strategic – this will depend on what you want a relationship to achieve once it has been identified.

The self-assessment tool is designed to be used flexibly. It can be used as a comprehensive three step process, with each stage developing consecutively and culminating in an overarching action plan. Alternatively, councils can choose to focus in on one specific part, dependent on overall aims, priorities and capacity. Each section is designed to both standalone and connect up as an integrated process.

Assessment one: The benefits of partnership working with the VCS

A key principle identified by our research was the importance of having a clear understanding of why strategic relationships with the VCS matter. Commitment to working with the VCS can often be the preserve of particular departments or a few key individuals. So an important starting point for any self-assessment is to develop a common view of the benefits of working with the VCS across the council to drive a shared commitment.

| Direct benefits |

|

|---|---|

| Indirect benefits |

|

Key questions for discussion:

- What are the key benefits for your council of working in partnership with the local VCS?

- To what extent do you think there is a shared understanding of these benefits across the council?

- Do you think there are areas where your council is currently realising these benefits? What lies behind this success?

- Are there particular areas where your council is missing out on these benefits? Is this because VCS capacity isn’t there – or is the capacity there and your council isn’t harnessing it effectively?

Assessment two: The type and scope of your relationships

Our research explored the many ways in which councils and VCS organisations interact with each other. In doing so, we identified five key ‘types’ of relationships. The typology below aims to help understand the main ways in which relationships are formed, rather than serving as an exhaustive list of potential relationships.

| Type | Shaping relationships |

Ongoing relationships |

Neighbourhood relationships |

Commissioning relationships |

Delivery relationships |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Summary | Formalised structures through which councils engage VCS on strategic direction. | Practical mechanisms for working together on a day-to-day basis. | Neighbourhood level structures for local engagement and where powers, funds, or service delivery can be devolved. |

Working together throughout the commissioning cycle. Planning strategically based on local needs, assets, aspirations, and priorities. Co-designing the services to be procured, and the process for doing so. Monitoring and evaluating based on agreed, meaningful, and illustrative metrics. |

Local VCS participating in tenders, winning contracts, and delivering local services. |

| Example | VCS Partnership boards and VCS strategies. | CVS and other infrastructure, compacts, Community Foundations. | Community councils, Area Arrangements, Place Partnerships, Community Networks. |

Co-design of commissioning strategies and/or services, being part of a public service framework, community asset transfer. |

Winning contracts, forming delivery consortiums, participating in alliance contract. |

We have found examples of how these relationship types are playing out for councils across the country.

In partnership with leading local VCS organisations, Derby City Council’s Communities team formed the Stronger Communities Board. This has been described as “a Trojan horse for the voluntary sector to occupy the council house”, as it was designed to be a purely VCS-led board leading policy debate.

Putting the VCS in the driver’s seat in this way has required other, unconventional approaches from new senior leadership. The council has also sought to create space informally for problem-solving, action learning, and open communication. This has been an iterative, ongoing process that has also helped bring the entire local VCS together. Such informal mechanisms have also supported co-production, often at early stages of project development.

This has provided an opportunity for the council to support the VCS to work alongside it to secure external funding. This transformed approach to strategic working has meant that commissioning doesn’t always need to go to tender. The approach has also demonstrated how co-production with the VCS can be accomplished not just within the Communities team but across the entire council.

Malvern Hills District Council have set up a ‘District Collaborative’ as a place-based partnership structure supporting the design and delivery of integrated services across localities and neighbourhoods. It involves the council, VCS, NHS, residents, service users and their carers, and representatives of other community partners.

Together, they seek to support the health and wellbeing of the population. The structured partnership holds summit meetings (30-40 people from around 25 organisations) to share experience and knowledge. It is helped by the council, which gives guidance, management, and support to the group. Importantly, it is chaired by VCS leaders.

The group meets regularly every six to eight weeks and people can take part depending on their needs (smaller organisations may not have the capacity to attend every meeting). “We don’t have to be the big people – no ego involved”, says one VCS leader. Building trust and solid relationships face-to-face is seen as key. The partnership uses these meetings to identify priority areas and agree a focus. From this, an action plan is devised to release funds, decide on the approach to take and the time and the resources it will require. The council asks itself, “who does this well already and who has the reach?” It understands that a council officer for everything is not the answer when significant strengths already exist within communities.

In assessing your own relationships, think about the main ways your council engages with and forms relationships with the VCS. Assess which relationships fall under each typology heading as well as who holds them.

Questions to ask of each relationship at this point include:

- Does it provide the VCS with a say over the direction of council strategy and policy?

- Does it support the regular and embedded engagement of the VCS in everyday working, for example through local infrastructure organisations?

- Does it target engagement on a neighbourhood-by-neighbourhood basis?

- Does it meaningfully engage the VCS in commissioning opportunities?

- Does it facilitate the delivery of council services by the VCS?

There may well be overlap between different relationship types. This is not necessarily a problem but should be kept in mind as you continue to analyse who holds the relationships and how effectively they are being used.

Understanding which departments, service areas, and individuals hold the different relationships may help to identify how strategic they are. While the seniority of the relationship holder does not dictate how strategic it is, it’s important to consider these points to identify where senior ownership may be lacking. There may be high-level relationships between senior council officers, councillors and VCS leaders. Others may exist within specific local forums or networks. Or they could be the consequence of day-to-day working by sector-facing officers within different departments. Again, not all of these need to be strategic. Assessment three can be used to decide which ones do.

These initial conversations should produce a broad map of current relationships, with an understanding of what they are, what they are for and where they sit. This map can also allow councils to consider where these relationships are held directly and where they are brokered through intermediaries like local infrastructure organisations.

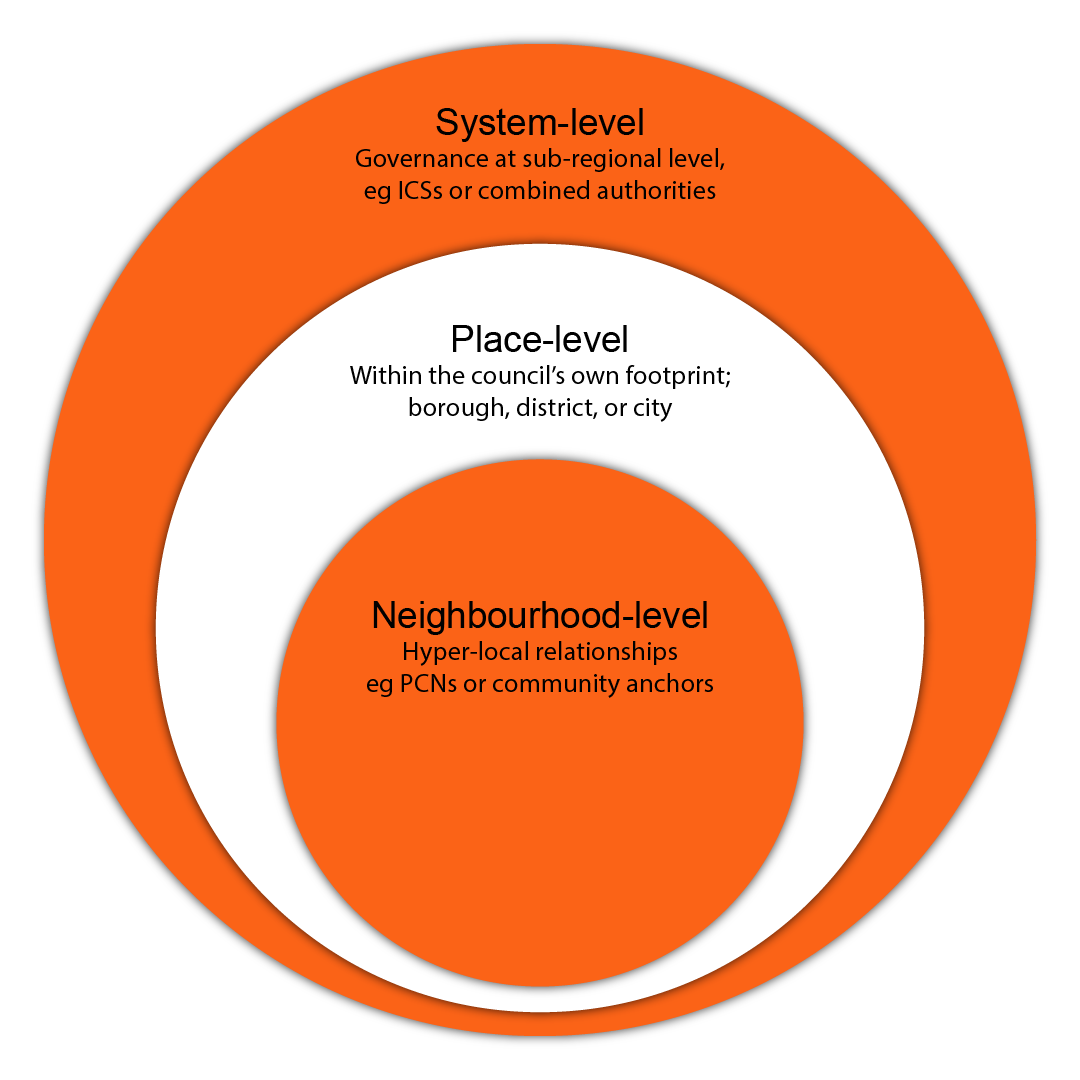

A further step to understand the scope, remit, and interplay of these relationships with the VCS, could be to map them spatially. Integrated Care Systems (ICSs) provide a useful example framework for this.

Assessment three: Evaluate how strategic your relationships are

There are no set criteria for what makes a relationship ‘strategic’ or ‘non-strategic’ – but the four principles for strategic relationships defined by our research suggest a set of qualities which can either be seen to be present or absent.

Together, councils and the local VCS should have:

- Shared foundations: clarity of purpose, values, and roles, built on shared understanding, knowledge and a commitment to partnership working

- Relational culture: behaviours and ways of working that enable the power of community to flourish, with both sides giving generously to the process and being open to receiving feedback

- Effective structures: systems, mechanisms and processes that are fit for purpose and enable innovation and sustain long-term commitment

- Capacity and resources: having the wherewithal to take action.

Below are just a few examples of the ways in which some of these principles are currently being put into practice in places across England.

In Derby, the council works with the VCS to tackle potential barriers of siloed working, clashes of opinion, and hesitance to collaborate.

It does so on two fronts.From within, council leaders have committed to adopting a community-minded approach and often challenge colleagues to work more closely with the VCS. From without, VCS leaders increasingly shape strategic direction through bodies like its ‘Stronger Communities Board’.

There is even an informal ‘Community Power Network’ consisting of council and VCS leaders committed to shared collaborative principles. This self-described ‘motley crew’ of individuals operates as a community of practice to exchange ideas “candidly, but confidentially”. Meeting fortnightly, group members share ideas, exchange resources and problem solve together.Historically, there has not been as much long-term planning around budgets as would be ideal. Where planning processes do exist, there have been tight timescales that preclude the VCS from shaping financial decisions. However, this is sometimes beyond the council’s control. A key example here are the Levelling Up Fund and UK Shared Prosperity Fund processes.

Due to tight timescales imposed by central government, the quick turnaround on both has made it more difficult to co-design a vision for the funds. However, leaders in both sectors have been working to overcome these challenges by ensuring that a broad shared vision is easy to understand and access. This vision can then be referred to so that decisions can be made on tight timescales rather than requiring repeated sign-off. This approach has included; a recognition in the council plan of the need to work alongside the VCS in designing services and delivering positive social change. The council’s ‘Community Leadership Manager’ regularly meeting with internal departments to devise ways their work can be more community-minded and inclusive of VCS voices. It also included council officers working hard to build up an institutional memory of strategic working with the VCS, embedding it in the identity of the council to better tell Derby’s story.

The approach to partnership working between Hackney Council and the local VCS has shifted over the years. Like most councils, Hackney has taken a New Public Management approach to delivering services over the last two decades. This has included Key Performance Indicators, best value and benchmarking with the aim of improving efficiency. There is a growing recognition that more collaborative ways of working are needed. Like others, Hackney is testing out partnerships that are more open, relational, and focused on shared outcomes and collective impact.

The council’s shift in mindset began after a realisation that VCS groups needed to be actively involved in working through collective problems and finding solutions. This has been key, for example, in tackling key inequalities in communities and meeting growing demand in advice services. It also came in response to the development of the council’s VCS Strategy, during which the sector flagged how transactional the relationship had become and the limits this imposed.

This approach helps address what are understood to be ‘complex’ problems with multiple determinants. These can be treated by embracing the multiple and complementary solutions provided by the broad and diverse VCS locally. Rather than see the VCS as one voice, the council’s leadership therefore works to recognise the collection of perspectives within the sector and create spaces for them to contribute to agenda shaping. This has been driven by the pandemic – the council had to start working in this way because, as it points out, “VCS partners were the only people who really knew what was going on in communities”.

Two VCS organisations – Clapton Commons and Shoreditch Trust – have worked together to re-imagine local VCS commissioning and present that feedback to the council. For their part, council leaders aim to align funding structures with the principles they hope to encourage in Hackney: collaboration, meaningful engagement, and solutions-minded approaches to community challenges. This has involved establishing ongoing dialogue with those in the VCS, including through strategic meetings and regular email correspondence.

South Gloucestershire Council has long sought to bring the VCS in as a “genuine partner around the table all the time”. This has meant having both formal and informal conversations regularly, importantly avoiding “tokenistic engagement” of the sector. This is especially important for adult social care. The council takes pride in increasingly acknowledging the strengths of the VCS through a Keep it Local approach to commissioning, amongst other activities.

That framework provides a shared vision for the council and VCS organisations and provides a foundation for work to be built on. Over time this has enabled trust to be built between the sectors which has only strengthened the relationship.In addition to these frameworks and principles for collaboration and genuine partnership, formal structures have been important in South Gloucestershire. The VCSE Leaders Board is the best example of this.

The formal VCS-led structure has been the backbone of collaboration across the council area. During the COVID-19 pandemic, it opened new avenues for collaboration as the VCS quickly mobilised.The Board was revolutionary in its approach. It is not a traditional partnership board where administrative power is held by the council and VCS representatives sit in on meetings. Instead, it has been VCS-led and has brought council leadership into the community. The board meets on a quarterly basis at times most convenient to the VCS partners. Its goal is to have a clear route for open dialogue between the council and the VCS in a way which preserves the sector’s autonomy and voice.

Its success has led to other boards being developed to provide a structure to joint-working. Among them is the South Gloucestershire Disability Network and the South Gloucestershire Race Equality Network. Both have regularly shaped key strategies and policy approaches alongside council officers.

Calderdale Council has a community anchor policy, thought to be the only example in the country. This very public commitment to proactively support the local VCS puts the sector at the heart of the council’s vision for a more inclusive local economy. In practice, the policy has meant putting in place a Relationship Management approach with established community anchor organisations. These tend to be the largest and most established local VCS organisations, often operating community spaces, employing local staff, and offering a variety of services to local people. Calderdale’s approach has provided a commitment from the council and local VCS to establish new ways of working and setting expectations for joint working. It also ensures that the VCS has access to council officers and practical and proactive support.

To assess a relationship against the four principles, consider the following questions.

| Principle | Questions |

|---|---|

| Shared foundations |

Does the relationship seek to rebalance power through collaborative partnerships, with parity of esteem, trust, and mutual respect? Is it supported by senior leadership? |

| Relational culture |

Does the council seek to use the relationship to enable and empower the VCS organisations to contribute their strengths? Is there also an understanding from the VCS of the areas in which they need to step up to deliver more? Do all parties approach the relationship with a view to learn and understand the position of others? |

| Effective structures |

Is the relationship part of a wider system designed to maximise the opportunities and benefits of council-VCS working? Does that system consist of suitable mechanisms through which relationships can thrive, eg, managed networks, forums, and programmes? Are their appropriate, consistent, and useful processes in place to facilitate good relationships and decision-making? |

| Capacity and resources |

Is there a shared commitment to prioritising and supporting each other with capacity to develop the relationship? Does the council support the VCS to access commissioning opportunities? Does it support local organisations representing marginalised groups to tackle entrenched issues of inequality in capacity and resource? |

The strategic measure of a relationship can also then be assessed by mapping it against a series of axes, including:

- Proactive-reactive – Are both parties engaged in the relationship to generate positive change (rather than being called into action only when need arises)

- Financial investment (high-low) – Does the council either use its own funds to engage the VCS organisation and produces outcomes, or support its access to other income streams?

- Time investment (high-low) – Does the council allot dedicated staff time to developing the relationship and its aims?

Scoring

An exercise this qualitative in nature and without a definitive definition of ‘strategic’ can never be an exact science. However, you might want to provide a score for each of the 15 questions/axes in Assessment three using this scale, to help you get a clearer sense of particular strengths and weaknesses and assess progress.

| One= Not at all | Two = To a small extent | Three = To a medium extent | Four = To a large extent | Five = As much as possible |

The higher the score, the more strategic the relationship is likely to be. Councils can loosely categorise their relationships according to their score:

- 0-15: Not strategic

- 16-30: Minimally strategic

- 31-45: Somewhat strategic

- 46-60: Largely strategic

- 61-75: Highly strategic

As we have discussed, not all relationships need to be strategic in order to be valuable. But this score can also help you to understand whether certain relationships have scope to be more strategic and should be nurtured as such. This can help identify whether a relationship is:

- Strategic in both intent and delivery – action not needed

- Strategic in intent but not in delivery – action needed to bring delivery in line with intent

- Strategic not in intent but in delivery – action needed to ensure delivery is understood, valued, and supported at a strategic level

- Strategic neither in intent nor delivery – action may or may not be needed depending on plans and opportunities for relationship

Creating an action plan

Following your assessment exercise, you should continue to work with the sector to create a joint action plan. This is an opportunity to clarify the understanding built through the process, define tangible next steps to strengthen strategic working, and decide who is responsible for taking it forward.

The content of the plan should be based on the following considerations assessed using the steps above:

- Gaps in the types of existing relationships, according to the typology

- Any overlap in the remit of relationships and the prospects for greater clarity within the council and between all parties

- How relationships can best be structured and supported according to their geographical scope

- Which relationships need support to become fully strategic, and what action needs to be taken to achieve this

- What balance can and should be struck by parties according to the axes mentioned above

- What needs to be done to improve how strategic relationships are, according to Assessment three, above.

To be as relevant and impactful as possible, any action plan must consider the external context in which it will operate. The four principles for successful, strategic relationships outlined in this toolkit are designed to be ‘all weather’ principles. They attempt to distil the key characteristics of good partnership working ‘in general’.

However, in practice they will be applied in a specific set of circumstances, determined by:

- an external policy environment shaped around shrinking council budgets and competitive commissioning

- long-term crisis conditions for VCS organisations at the local level, following a decade of austerity, and the pressures of the pandemic moving into a cost of living crisis.

It is therefore important for local areas to think about the implications of these contextual factors and what they mean for putting these principles into practice. For example:

- Has the pandemic built shared foundations by increasing councils’ appreciation of the VCS’s work? Or has it instead seen these organisations “boxed” off as emergency delivery partners?

- In recovering from the pandemic, councils may have been moved to better collaborate with their communities on shared aims and ambitions for their place. But how do they build this relational culture in an intentional and meaningful way?

- Innovations such as Integrated Care Systems may well aim to revolutionise the way the VCS and public services work together locally. But how do you bring the VCS along on this journey to create effective structures, rather than creating confusion around yet more change?

- Councils may have good intentions to build the capacity and resources of their VCS organisations. But how feasible is this against the backdrop of a financial crisis and looming budget cuts?

The examples highlighted in this toolkit and explored further in the report show how different council areas are overcoming these challenges to put these principles into practice. While it is important to recognise the difficult circumstances within which strategic relationships are seeking to grow, there is a clear consensus from our research that the only way through them is to work together.