Executive summary

In the 2023 Spring Budget, the Chancellor announced additional funding to support local authorities to expand wraparound childcare (before and after school) between 8am-6pm for all primary aged children. Coram Family and Childcare was commissioned by the Local Government Association to conduct research with parents, sector experts and local authorities to build an understanding of current provision and how councils might use the additional funding to support the expansion of provision. The policy is rooted in the government’s employment agenda, encouraging parents to work and a mandated requirement for parents on Universal Credit with primary school aged children to work more hours but also serves a dual purpose of potentially improving access for disadvantaged children to extracurricular activities to improve their outcomes.

Coram Family and Childcare’s most recent Childcare Survey 2023, highlights the current gaps in wraparound childcare provision for primary school age children – with only one quarter of local authorities having sufficient provision for parents working full time with children aged 5-11 and over a quarter of local authorities not having a clear understanding of the provision in their area.

In terms of the preferences of parents, and the views from sector experts, there is not one preferred model of delivery between direct school provision, private or voluntary providers or childminders. What parents and sector experts wanted was good quality provision that reflects the needs of all children, including those with additional needs, and that any new or developed provision must be sustainable and delivered at a reasonable cost. There was concern that the funding was not supporting an expanded holiday childcare offer, which was seen as a key missing piece in enabling parental employment.

Local authority webinars and interviews with four local authorities, Islington, North Somerset, North Yorkshire and Hartlepool were subsequently carried out to develop the key themes and recommendations for change.

Please note that the recommendations in this report are that of Coram.

Key recommendations

We hope that this report will help to inform and support local authorities to gauge and understand how demand in their local area is likely to change as a result of the Chancellor’s announcements in the Spring Budget. The extra funding, and the focus on primary school age childcare is welcome, and provides the opportunity to address an area where there have been persistent shortages in sufficiency. We also hope it can be used to support the primary school age childcare sector to grow to meet this expected additional demand. Below we set out key recommendations.

Need for understanding of local demand

Local authorities must develop a clear understanding of current and potential future demand for wraparound childcare, this will enable them to support their local childcare market/providers and invest funding into provision that will be sustainable in the medium to long term.

To do this, they must regularly gather broad information across their local area, and also detailed granular data in areas where there could be childcare shortages, including working with parents to understand exactly how much childcare they are likely to use, their preferences for childcare, and how much they are willing to pay for it.

Support for parents wanting to move into work

Some new demand for wraparound childcare is likely to come from increasing work expectations for parents with primary school aged children claiming Universal Credit. Local authorities and ‘childcare champions’ at Jobcentre Plus should set up local partnerships, that help parents find childcare that enables them to work, and supports local authorities to understand the likely changes in demand.

Support to grow the wraparound childcare workforce

Local authorities can help support entry into the wraparound childcare workforce, particularly through supporting childminders and leveraging the current start up grant available. Local authorities should set out a plan for how to help childminders caring for primary school age children, such as making civic space easily accessible for trips for childminders and supporting childminder networks. Local authorities should also work with their education providers to look at employment routes both during and after study to help expand the wraparound childcare workforce.

Improvements for children with SEND

The expansion of provision must be inclusive for children with additional needs, both within mainstream schools and specialist schools. In relation to specialist schools, it will be important to reconcile any expansion of wraparound provision with what can be rigid times with home to school transport. The government should issue guidance for local authorities on how they can address the current shortages for children with SEND, how to meet any additional costs associated with provision and how the extra funding from the Chancellor could be used to meet those costs.

Link to holiday childcare

Many parents need year round childcare to stay in work, and local authorities have a duty to make sure there is enough childcare for all working parents. Although the additional funding can only be used to support wraparound childcare, local authorities should think about year round childcare for school age childcare, and taking account of the fact that many school age providers need to operate year round in order to be financially sustainable.

Affordability of wraparound childcare

The handbook for local authorities highlights the need for local authorities to raise awareness of both tax free childcare and the childcare element of Universal Credit. Local authorities should use their own communication channels and work with their providers to help increase awareness of this support. To make sure the greatest reach, the government should also consider running a national awareness raising campaign to back up local communication.

Introduction

Coram Family and Childcare was commissioned by the Local Government Association to conduct research into wraparound childcare. Wraparound childcare is defined in the National wraparound childcare programme handbook as childcare that ‘wraps around’ the school day, or provision for school-age children directly before and after the conventional school day.

The research builds an understanding of what provision is currently on offer and helps inform how councils might use the new funding outlined at the Spring Budget 2023 to improve the supply of wraparound childcare.

The report includes a background of wraparound childcare policy, the recent government announcements about the policy, and facts about childcare. We conducted a focus group with parents and Parent Champions as well as interviews with experts on childcare delivery and policy. Parent Champions are parent volunteers who talk to other parents about the local services available to families. The Parent Champions scheme was introduced to help marginalised or isolated parents who miss out on information on accessing local family services. After these interviews, we ran webinars with local authorities across England, to share our findings and to discuss approaches to expanding wraparound provision. We then interviewed four local authorities with different approaches to wraparound childcare and we have set these out in case studies.

We conclude the report with recommendations and policy implications for local authorities in relation to the expansion of wraparound childcare.

Policy context

Background

Wraparound childcare achieves two purposes: it enables parents to work and can support disadvantaged children to access extracurricular activities to improve their outcomes. Over the last 30 years there have been a series of local and central Government interventions to support these outcomes and improve access to wraparound childcare.

The sector has expanded rapidly since 1990, when there were only 350 school-based clubs in England and Wales providing 5,000 childcare places. The Labour Government ran their ‘out-of-school childcare initiative’ between 1997 and 1999, which raised the number of school-based childcare places for children aged 5 to 11 to 40,000. Labour’s 1998 ‘Meeting the Childcare Challenge’ green paper committed the Government to improving both the affordability and availability of childcare using a mixture of private, not-for-profit and public sector provision.

In 2002, the Department for Education and Skills developed the ‘extended schools’ programme. The definition of extended schools included a wide range of services including counselling for children, employment training for adults, and childcare provision before and after school. A pilot programme of 25 local authorities found that extended schools improved educational achievement, parental employment and community relations.

In 2004, Labour announced their aim to create a school-based childcare place for every child in the UK aged three to 14 within 10 years; in England, the extended schools programme would deliver this. In 2005, the Government signalled a shift from ‘extended schools’ to ‘extended services in and around schools,’ placing schools as facilitators for other agencies, and committed all schools to providing a core set of extended services by 2010, including an 8am to 6pm day offer, 48 weeks a year. Concurrently, the Childcare Act 2006 established the requirement for English and Welsh local authorities to ensure their areas have sufficient childcare for children up to the age of 14 whose parents are in work or training for work. This gave local authorities a clear role in the development of extended schools and wraparound childcare.

The extended schools programme identified five core elements of the extended schools offer:

- childcare from 8am to 6pm, 48 weeks a year for primary schools.

- a varied menu of activities (including study support, play/recreation, sport, music, arts and craft and other special interest clubs, volunteering and business and enterprise activities) for primary and secondary schools.

- parenting support, including family learning.

- community access to facilities including adult learning, ICT and sports facilities.

- swift and easy access to targeted and specialist support services such as speech and language therapy.

By 2010, two thirds of schools offered all five elements of the full core offer of the extended schools programme and the remaining third offered some of these elements. Evaluations of the programme tend to have focused on outcomes for children rather than effects on parental employment. A 2010 survey, found that 68 per cent of schools said that extended school services had at least some influence in raising attainment and 13 per cent said it had ‘considerable influence.’ These findings were replicated again in 2016; disadvantaged primary school pupils who attended an afterschool club once a week achieved, on average, a 1.7 point higher Key Stage Two score than predicted based on their prior achievement. The benefits were most evident for disadvantaged children – those who attended an afterschool club twice a week outperformed expectations by three points, as outlined in Centre for Longitudinal Studies report.

In 2011, ring-fencing for extended schools funding was removed and, in a time of spending pressures, school-based childcare clubs became less financially sustainable and there were closures. In 2013, the Coalition Government’s ‘More Affordable Childcare’ policy paper set out its intention to make it easier for schools to offer childcare and community facilities on-site and, in 2014, the Children and Families Act 2014 removed regulations from the Education Act 2002 that required governing bodies to consult before making school facilities available to the wider community. By 2016, the extended schools funding still formed part of the Designated Schools Grant (DSG) in England but there was little analysis of how this money was used, and the DSG was under considerable pressure during this period.

In 2016, the Conservative Government introduced their ‘right to request’ policy with the aim of helping parents to work, or to work more hours, by increasing the availability of wraparound and holiday childcare. Under the policy, parents of children from Reception to the end of Year 9 can submit a formal request to their child’s school asking them to provide wraparound or holiday childcare. According to Government guidance on wraparound and holiday childcare, the school is then required to gauge wider demand for the requested services and to inform parents of whether or not they will accept or deny the request and the reasons for their decision. All schools are expected to provide wraparound childcare, from 8am to 6pm, if there is sufficient demand. In practice, local authority staff have said that parents are either unaware of, or unable to make use of, the ‘right to request’ procedure and there was little clarity on the expectation around what should be delivered. Responding to surveys conducted in 2017 and 2018, only three to seven per cent of local authorities said the policy was having a positive impact on sufficiency of childcare.

Proposed expansion of wraparound childcare

The Chancellor, Jeremy Hunt MP, announced in his Spring Budget in March 2023, an investment of £289 million over two years from September 2024, to enable local authorities to support the expansion of wraparound childcare for all primary school aged children from 8am to 6pm. The wraparound expansion is around term-time provision and does not include the school holidays.

The government subsequently announced that 16 local councils had been chosen to develop pathfinder wraparound childcare delivery plans. The local councils include Barnsley, Blackburn with Darwen, Cambridgeshire, Central Bedfordshire, Cornwall, Dudley, Gateshead, Hampshire, Hartlepool, Kingston upon Hull, Merton, Newham, Norfolk, Nottinghamshire, Sheffield and Wiltshire. The government has also established, at the Department for Education, a Wraparound Policy Steering Group to support the development and rollout of the wraparound childcare policy. In addition, the government has recently published the National Wraparound Childcare Programme Handbook: A guide for local authorities in England (October 2023).

The Chancellor’s policy announcement around wraparound childcare, was made in the context of the government wanting to support parents to work more hours or to enter the workforce. This policy perspective is clear from the response by the Secretary of State for Education to a Parliamentary Question about the expansion of wraparound childcare which includes the observation that parents are working fewer hours even when their children are school age because of the current gaps in provision and that “40 per cent of non-working mothers with primary age children said that if they could arrange good quality childcare that was convenient, reliable and affordable, they would prefer to work”. So, the expansion of wraparound childcare is focused on increasing parental employment rather than on child development, although it may deliver benefits to children.

Expansion of wraparound childcare and increased welfare conditionality

An expanded wraparound childcare provision may support some parents who want to start work or work more. However, the Spring Budget mandates an increasing number of parents on Universal Credit to become jobseekers or to increase their working hours. The wraparound childcare policy runs in tandem with the expectation on low-income parents in particular to move into work or to increase their hours of work.

Families on Universal Credit have rules in place, known as welfare conditionality, as to how many hours they are expected to work or to spend job seeking. Welfare conditionality has changed over the last fifteen years with an increasing expectation on parents to work or job seek. Currently single parents and lead carers in couples are expected to become job seekers when their youngest child is aged three. As well as expectations about who must work, as a condition of receiving Universal Credit there is also the requirement as to how many hours parents should work. Up until October 2023 the maximum hours requirement for single parents and main carers was twenty-five hours for those whose youngest child is aged between five and twelve years. For some this has meant they may be able to work during school hours with less need for before and after school childcare.

Since October 2023, main carers (mostly mothers) and single parents with a child at primary school are now expected to work thirty hours a week. An additional 800,000 parents will be expected to increase their hours of work or move into work for the first time.

The wraparound childcare expansion therefore comes in the context of an increasing expectation for many lower income families to increase their hours of work or enter the workforce. Local authorities will need to take into account both those parents who may voluntarily wish to take up childcare or increase their use of wraparound childcare as well as those who will be obliged under benefit rules to work more hours when they calculate the demand for provision. The expectation on single parents and main carers in couples to work thirty hours a week is likely to have a particular impact on the demand for wraparound childcare provision for primary school aged children.

Quality of wraparound childcare

Since September 2019, according to Ofsted guidance, childcare clubs do not have to meet learning and development requirements, unlike early years childcare providers, and the Ofsted grading system for childcare clubs has been simplified to focus on whether or not safeguarding requirements have been “met” or “not met.” These changes were made in response to an Ofsted consultation which found that the ‘quality of education’ requirement was not appropriate for childcare clubs because they are not required to meet the EYFS learning and development requirements and that many providers of school-age childcare clubs do not consider themselves to be an education service.

Many, but not all, childcare clubs are required to register with Ofsted; providers who care for children under the age of eight for more than two hours a day must register with Ofsted. More details on requirements are available on Out of School Alliance website.

Ofsted has two registers for childcare providers: the Early Years Register (for children from birth to the 31st August after they turn five; most children in reception year at school fall under this category) and the Childcare Register (for children from the September after they turn five until they turn eight; most wraparound services fall under this category). The Childcare Register has a Voluntary and Compulsory section; the former is for activity-based clubs and providers that care for children older than eight.

Ofsted inspections of childcare clubs have three possible outcomes, guided by the below government guidance principles:

- Met: this means that the provider complies with all the requirements.

- Not met – actions: this is likely to be for minor failures to meet the requirements that have a minimal impact on children and/or issues that can easily and quickly be corrected and/or the provider demonstrates a clear ability and willingness to put right.

- Not met – enforcement action: this is likely to be for more significant failures or persistent failures to meet the requirements that have a direct impact on the safety and welfare of children and/or the suitability of the provider.

Providers registered under the Compulsory Childcare Register must fulfil several requirements:

At every session you must have:

- a first aider holding the 12 Hour Paediatric Care First Aid qualification

- all your staff must have been trained to understand your safeguarding policy and procedures and have received training in recognising signs of abuse and neglect

- all your staff must have received training in recognising the signs of radicalisation and know how to respond to concerns

- all staff involved in food preparation must have had some form of food handling training but not necessarily a formal Food Handling and Hygiene certificate.

Among your staff — and ideally at every session — you must have:

- A designated child protection person, who holds a Child Protection Level 1 or Basic qualification, and who has attended a Child Protection Designated Person training course.

Among your staff you should have:

- A fire safety officer is not a statutory requirement but it is good practice to have a named person taking responsibility for fire drills and record keeping.

While the quality requirements for school age childcare providers are light touch, quality does matter to the families using school age childcare. Our research on school age childcare in London found that parents were reluctant or unwilling to use childcare that they did not think was high enough quality or that their child(ren) did not enjoy. Parents and Parent Champions who attended our focus group on wraparound childcare (set out later in this report) also talked about the quality of provision. It is important to consider parent and child demands and preferences around school age childcare in order to achieve both employment and child development outcomes.

Current wraparound childcare costs and availability

Wraparound childcare costs

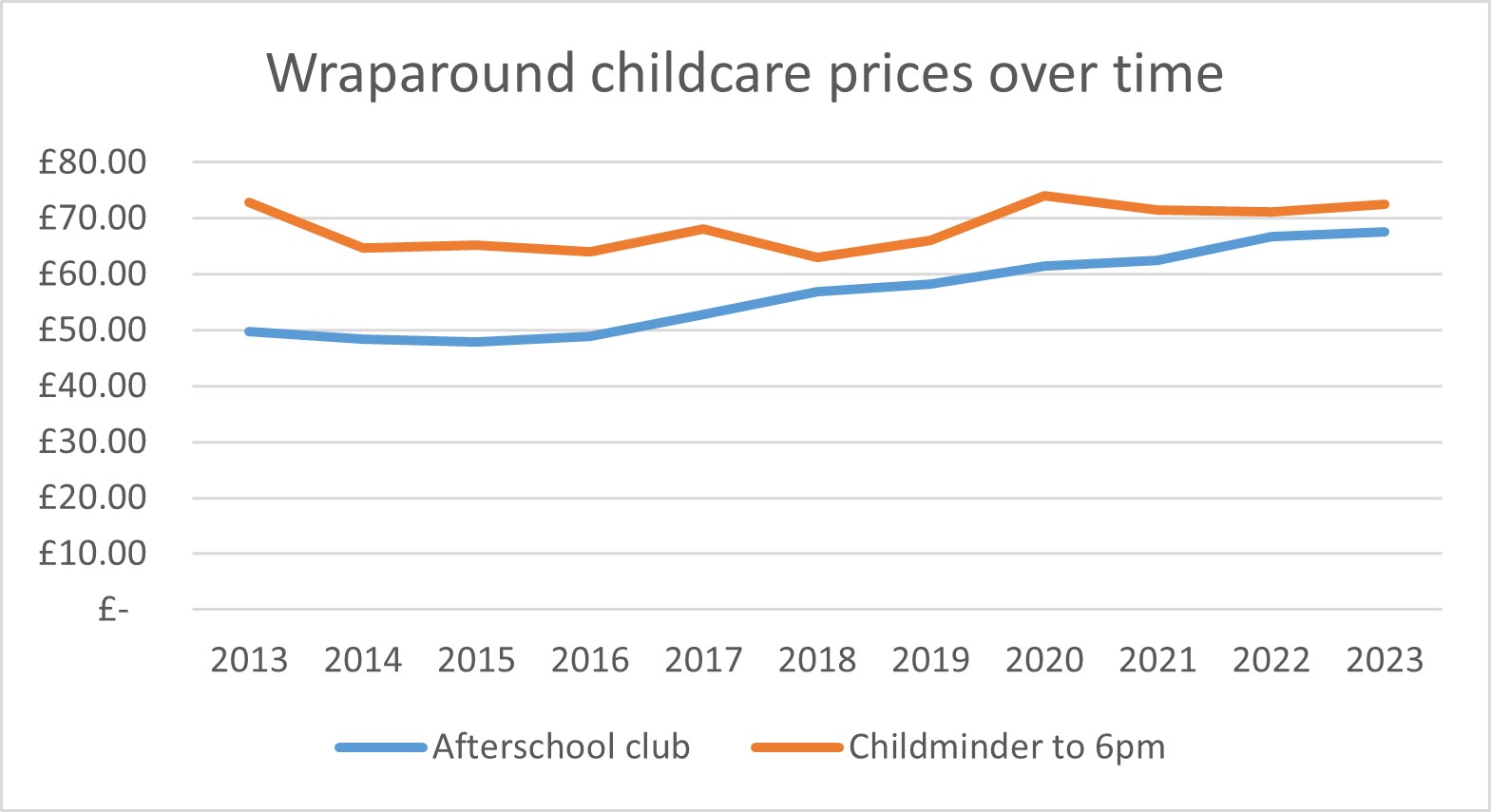

Coram's childcare surveys have shown afterschool club prices rising steadily over time (figure 1) and a narrowing in the price difference between afterschool clubs and childminders.

Figure 1 shows the the price of a wraparound childcare place per week since 2013

Source: Coram Family and Childcare, childcare survey 2013 – 2023

Wraparound childcare availability

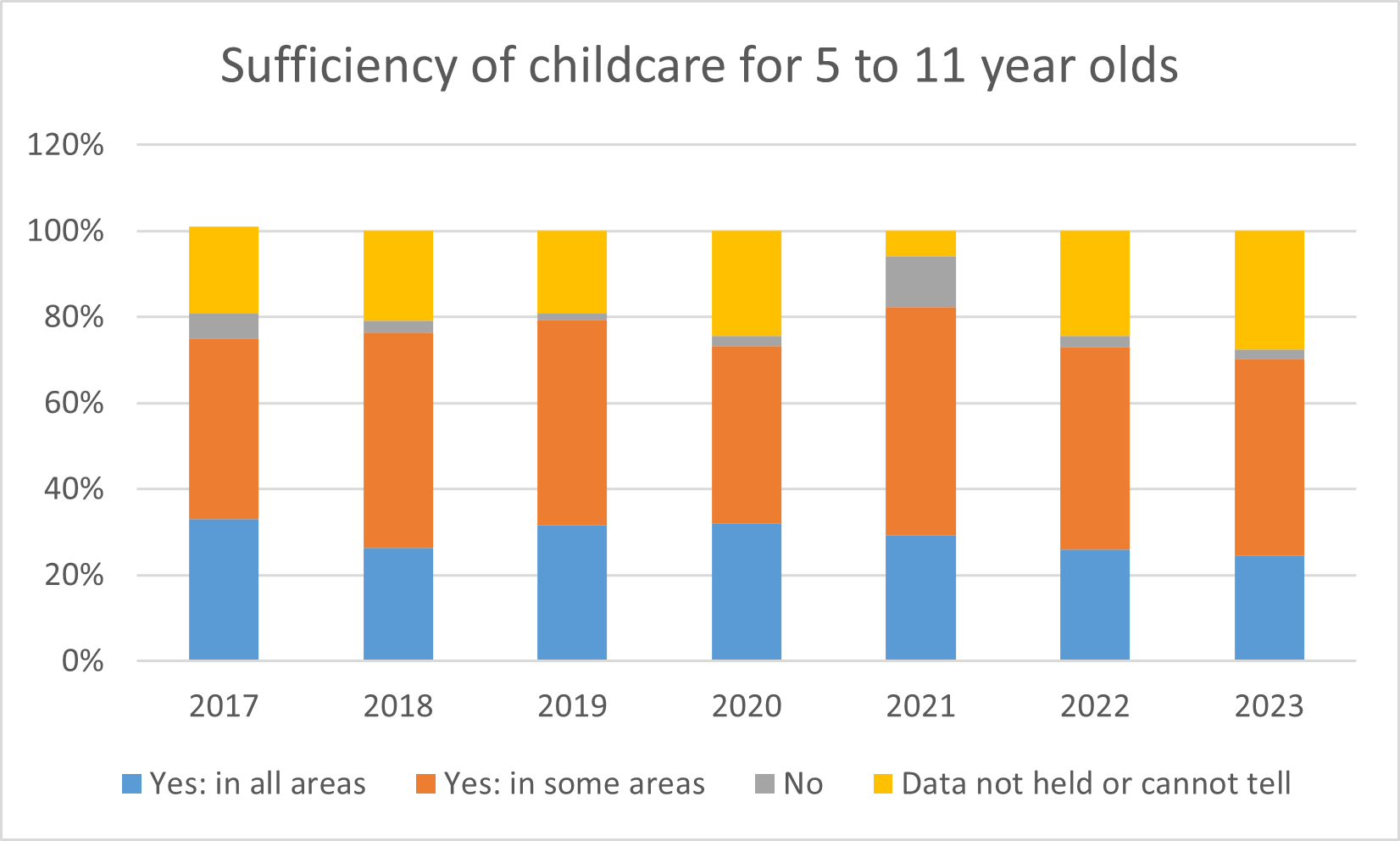

Coram Family and Childcare’s Childcare Surveys also find persistent shortages in the sufficiency of childcare for primary school age children with only a quarter to a third of local authorities reporting enough childcare for children aged five to 11 since 2017 (figure 2). During this period, there has also been fluctuating demand for wraparound childcare. The percentage of school-age children accessing any form of childcare has steadily decreased according to government data, from 71 per cent of five to 11-year-olds in 2017 to 59 per cent of five to 11-year-olds in 2022. Covid lockdowns, social distancing measures and changes in work and caring patterns caused significant disruption to the wraparound childcare market and go some way to explain the dip in availability during the Covid period.

Given some wraparound childcare provision is not registered with Ofsted, it is hard to track provision, and this was particularly challenging during Covid when it was often unclear what was happening to wraparound childcare provision. It should also be noted that school-based childcare provision is not consistent throughout England, and it is usually disadvantaged families who miss out. Schools with a higher proportion of children eligible for Free School Meals (FSM) or who speak English as an additional language (EAL) are less likely to have breakfast and afterschool clubs than schools with a higher proportion of children from a white British background or who speak English as their first language, according to Coram Family and Childcare's report School age childcare in London.

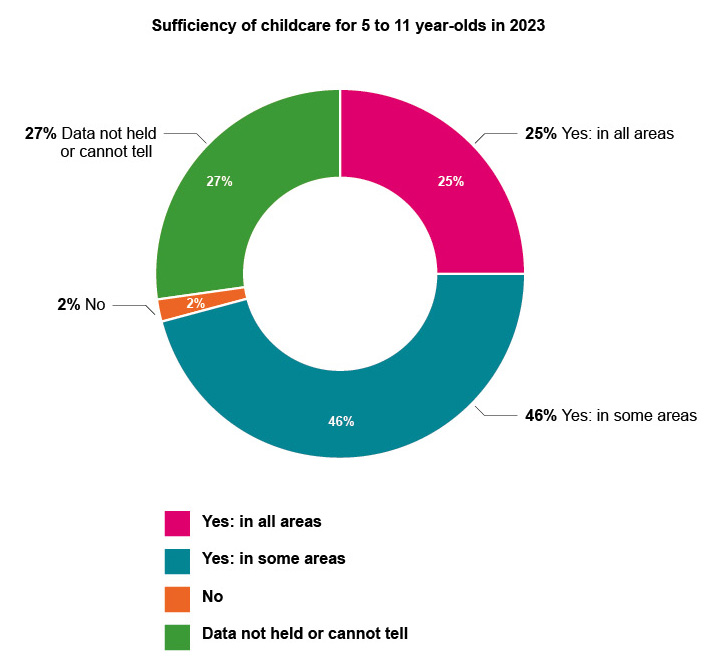

Latest figures on wraparound childcare sufficiency

The most recent Childcare Survey 2023 figures around wraparound childcare, found that for parents who work full-time and have a child aged five to 11 only 25 per cent of local authorities report that there is sufficient provision in all areas; 46 per cent in some areas; 2 per cent that there is no sufficiency. Crucially, for 27 per cent of local authorities this data is not held or they cannot tell. This clearly illustrates the current gaps in wraparound childcare provision for primary school age children, with a significant minority of local authorities not having a clear understanding of provision in their area.

Figure 3: Sufficiency of childcare for five to 11 year olds in 2023

Source: Coram Family and Childcare, Childcare Survey 2023

Practice background

In order to understand the wider context for wraparound childcare delivery, we ran five expert interviews with organisations representing key stakeholders in wraparound childcare: private providers, schools and parents. Similar themes came out from across the interviews. We also ran a focus group with parents and Parent Champions to make sure that our understanding was grounded by parents’ needs and preferences.

Provider type and operating models

There are a number of different operating models currently being used: schools running their own wraparound childcare provision; private or voluntary providers operating out of school premises; private and voluntary providers operating out of non-school premises; and childminders working in their own homes. There was not a strong preference for any of these operating models being better than others, but instead a view that any of these could be done well or badly.

“There is not one model that works above all others.” (Sector expert)

There are opportunities for consistency and familiarity in all these models, with teaching assistants often also working in wraparound childcare both when run by schools themselves or private providers. Some parents noted the benefit of wraparound childcare in a school setting where children were already familiar with the environment and could be with their friends.

“So, four days provision that I put my daughter in and, because it’s amongst her friends, her school, her environment she’s familiar with it’s worked out well.” (Parent)

Parents also spoke about the value of delivery at school and by childminders.

“If it is at school, they carry on playing with their mates and their friends and that enhances social skills. If it is a childminder…they get to meet other people and they get to play with other children and they learn different things. So, I think there is a massive benefit to them as well.”(Parent)

A school that we spoke to moved to running their wraparound childcare in house when the private provider had to withdraw when demand reduced during Covid. They saw benefits from now running this in house as they were able to be more flexible for families who needed extra childcare at short notice.

“It is useful because we have really been able to listen to the parents and their needs and come up with a wraparound service that reflects their needs and work patterns.” (Sector expert)

Equally, we heard about private providers who had taken over provision previously run in house by schools and were able to offer a more reliable service. However, some interviewees noted structural elements that alter running costs for different types of providers, and in turn parental fees and/or financial sustainability. Schools tend to need to pay higher wages to staff compared to private providers and are also more likely to offer more generous terms and conditions. Private providers normally need to pay rent for the premises, unlike school-run provision, and the rate for rent can vary dramatically between different schools.

We heard of the importance of developing wraparound childcare provision that it is sustainable.

“Future proofing is about not rushing to make a decision to fund and to open something new… I don’t want to see a churn of providers.”(Sector expert)

Preventing this churn of provision was seen as vital for parents.

“It does not matter who is providing the wraparound childcare but it does need to be stable. Establishing childcare that then just closes a short while down the line means that parents are back to square one.” (Parent)

Some parents felt that childminders were particularly important for children with Special Educational Needs and Disabilities (SEND) who could benefit more from a smaller, quieter setting and lower staff to child ratios.

One parent said they had always used a childminder for wraparound care because their childminder was good with “additional needs” and that the home environment is more suitable for children with SEND who “need small groups or 1:1 or even 2:1.”

Understanding quality

The parents talked about the need for a range of activities to meet children’s different interests. One parent spoke positively about their afterschool club offering a different activity each day, whereas another raised concerns that their afterschool club focused too much on sport which did not match their child’s interests. The skills and empathy of the staff were considered more important than the activities that were on offer and parents particularly prioritised this. They also wanted staff to have up to date training and skills on working with children with SEND to be able to support all children.

Some parents also said that their children found the clubs boring, both in terms of the activities and the food that was on offer, and that breakfast clubs in particular tended to have fewer activities on offer. Parents valued big open spaces and were pleased that the provision that they used did not have any screen time. Parents also spoke positively about breakfast clubs enabling children to be well fed before starting the school day, although others raised concerns about the variety of food on offer.

“It is really handy (the breakfast club at school) so I could drop off my child and he gets his breakfast and there is a good variety of things he could play with and be with his friends.”(Parent)

There was not a clear shared vision of what high-quality wraparound childcare looks like in the expert interviews. Many discussed the challenges around making sure there was enough childcare for children with SEND, but beyond that, there was not a clear definition of good quality provision. Key elements of quality that were discussed included being able to understand the wants, needs and preferences of the individual group of children and adapt provision to meet those.

“Good provision is about listening to what the children want and excellent communication with parents. The space is important. We are able to offer inside and outside space to children. It allows children to do lots of different activities within the school setting in a safe environment.” (Sector expert)

It was felt that operating at the maximum ratio (1:30) did not allow for this approach. Some interviewees described quality as being about enabling children to relax and have fun, rather than being about formal activities that support children’s development.

“We don’t want to hijack this wraparound programme to become an enhanced school programme.”(Sector expert)

Expanding the workforce and maintaining quality

There were also concerns about how the expansion could affect quality. The regulations around school age childcare are less prescriptive than for preschool children, including around qualifications and checks of staff. While there are pressures around recruitment and retention right across the childcare sector, for wraparound childcare this could create particular risks around whether it is possible to get the right people with the right skills to fulfil the role.

“I think the challenge is going to be finding people who actually want that kind of work, which is an hour in the morning, 3 hours in the afternoon, it won’t suit everybody.” (Sector expert)

There was concern from providers about the difficulty of finding staff who were willing to work an hour in the morning and from 3.30-6pm. Some providers had managed to find suitable workers from local colleges who combined their study (often in a related field of study) with working in wraparound childcare, indeed the before and after school hours often suited their hours of study and they could be available where providers also offered holiday childcare. It was stressed that those who worked in wraparound childcare needed to have different skills from the early years workforce, including more play based approaches focused on the needs of older children.

“Wraparound childcare staff need different skills… There needs to be a play and child centred approach.” (Sector expert)

Flexibility of provision

The latest Government funding is aimed at setting up provision to operate from 8am to 6pm, unless data shows that local demand is for different hours reflecting local labour market patterns. From the focus group and interviews there were varying views about whether 8am-6pm hours are sufficient to meet the needs of working parents.

Parents did not think that provision was always flexible enough to reflect their working lives. They felt providers could be too rigid around needing to book sessions far in advance, there were not always sufficient places, and the hours could be too limited. Some said that they were expected to use breakfast provision all or most days in order to keep their place, which did not always match their needs.

Some parents wanted longer hours than 8am to 6pm, even just starting at 7.30am as some nurseries do. The issues with hours were felt particularly strongly by parents who do not work typical 9am – 5pm hours who felt poorly served. This could also be the case for parents who had a longer commute time for work.

“That is a barrier and challenging for us parents because of the extra travel time for work. It is also a barrier to applying for jobs. Even for jobs in a school it does not work because you have to start as early as 8 so you couldn’t get from your own child’s school to get to work on time.”(Parent)

While providers felt that they were largely meeting families’ needs, others raised the issue of parents needing longer hours in order to be able to manage work and commuting time. This was felt to be particularly important for single parents who are less likely to be able to share pick up and drop offs.

“The traffic can be hard for people who work in the local town, it is only four miles away but it can take time and so finishing at 6 gives parents enough time to finish work at 5.30 and get to the school.” (Sector expert)

One expert Stakeholder suggested that even longer operating hours of 7am to 7pm would be more useful to parents, but others felt that the hours that were currently on offer were sufficient for parents.

Longer opening hours would increase running costs for providers who would need professionals to work longer hours and to have access to premises for longer, and so it is likely that these costs would need to be passed on to parents. There would also need to be a greater understanding of whether there was enough local demand to increase opening hours and to make this financially sustainable.

Children with Special Educational Needs and Disabilities (SEND)

There were particular concerns from parents about whether there was enough childcare for children with SEND and that the funding available for them was often inadequate. One parent, observed from her own experience that “parents with children with additional needs are excluded from wraparound childcare”.

A parent champion said, “The biggest complaint I hear from parents with children with additional needs is that there is not enough before and after school provision for them, they need either small groups or one to one, or even two to one and childcare providers just can’t do that because it is not financially viable for them.”

Another parent pointed out that there were financial issues for those who wanted wraparound care delivered by a childminder, as the additional costs to the childminder meant that they could be reluctant to take on a child with additional needs “Not even childminders can take them (children with additional needs) because it is not cost effective.”

Both parents and stakeholder experts felt that children with SEND were particularly poorly served by the current wraparound childcare market. Providers are not able to access additional funding for children with SEND, and most providers’ income comes from parent fees. This means that any additional costs associated with specialist provision needs to be met through parental fees. Interviewees noted that the high child to staff ratios at wraparound childcare do not always help with making provision accessible to children with a range of additional needs.

“The one thing that restricts us is having the staff to look after children with SEND. There is no funding for having one to one staff for these children or it is very hard to get.” (Sector expert)

“We do the best we can for SEND children. We are already operating on a shoestring. We need to keep costs down as much as we can.”(Sector expert)

Reasonable cost

Parents wanted wraparound provision to be available at a reasonable cost. They also wanted more publicity about financial support for childcare including tax free childcare and help under Universal Credit to help make wraparound childcare more affordable. It is positive that the handbook to local authorities also stresses the need for local authorities to promote the use of this childcare support.

In the local authority webinars that we held, attendees thought that there is a role for central government in promoting a national campaign to highlight this support to parents. Parents were concerned that any new funding from the Government for wraparound care would go to commercial companies. Parents thought it would be better if there could be investment locally and for social enterprises to lead wraparound care in schools.

“I don’t mind paying but not too much. That’s not a problem, but I think it needs to be reasonable and affordable to parents.” (Parent)

Understanding need

In the expert interviews, a common theme was around the difficulties in accurately assessing need for wraparound childcare, and therefore being able to design services meets this need. While local authorities hold a duty to ensure sufficient childcare for all working parents, childcare sufficiency assessments are often stronger at assessing demand and supply of pre-school childcare rather than school age childcare.

“The nature of childcare sufficiency for school age children is hard, parents might say they want childcare at their school but when that provision is established they might not take up a place. From a provider’s perspective you need committed sign ups in order to commit to opening a setting.” (Sector expert)

For some, they thought the solution was being very upfront with parents about potential costs and asking them to be clear about their anticipated usage over the week and the term rather than a vaguer question to parents as to whether they might use wraparound childcare at their school.

“There needs to be real data and real information rather than a parent saying ‘yes’ but then only using childcare every four weeks. Providers also need a clear understanding of who else is around you. Is there really a need for new provision or is there enough already there?” (Sector expert)

Coram Family and Childcare have also seen in research greater volatility in demand for school age childcare, particularly around Covid and this was also highlighted by sector experts.

“I think that Covid has specifically impacted and had a negative impact on out of school provision, more parents partly work from home and commute less. It has meant that some parents can do their job around the school day and this has had an impact on providers of wraparound childcare.” (Sector expert)

Sector experts talked about consistently seeing shortages in sufficiency, but that it is hard to quantify these to a particular number of places in a particular area. In some areas, there is demand for school age childcare, but not enough to maintain self-sustaining breakfast and afterschool clubs – meeting this need is particularly challenging. A clear understanding of demand in hyper local areas will be important, and challenging, for local authorities as they work to increase the supply of financially sustainable wraparound childcare and that this accurately matches demand, at a time when we expect demand to increase.

“We have had links with other clubs that have closed because of lack of demand and they could not make ends meet. They were not sustainable in the longer term. This is true of private providers as well as provision delivered by schools.” (Sector expert)

School holidays

While interviewees welcomed the recognition of the need to support primary school age childcare provision, there were also concerns that only focusing on term-time childcare was a missed opportunity and would not meet families’ needs.

“Providing term-time only wraparound care is not going to solve the issue of childcare for working parents.” (Sector expert)

Many felt that the pressures were currently greater during the holidays rather than term-time and that by not supporting holiday childcare, the intervention was unlikely to achieve its aim of supporting parents to work.

“There are holiday camps that are happening for pupil premium children and children on school meals but this is not helping other parents who are struggling to arrange holiday childcare.” (Sector expert)

Another talked about the value that there can be in providing holiday childcare connected to the term-time provision, and this was achieved through grouping across different schools rather than provision in each. Providing both holiday and term time provision can be the only way for some providers to be financially sustainable.

“The government are missing a trick not including provision in the school holidays. We have parents working shifts all year round, so you need to be there all year round for some of these children. I have got parents who would not be able to work if we were not there in the holidays.” (Sector expert)

Key recommendations

Coram hope that this report will help to inform and support local authorities to gauge and understand how demand in their local area is likely to change as a result of the Chancellor’s announcements in the Spring Budget. The extra funding, and the focus on primary school age childcare is welcome, and provides the opportunity to address an area where there have been persistent shortages in sufficiency. We also hope it can be used to support the primary school age childcare sector to grow to meet this expected additional demand.

Below sets out key and policy recommendations.

Need for understanding of local demand

It is essential that local authorities gain a clear understanding of current and potential future demand for wraparound childcare and be able to invest funding into provision that will be sustainable in the medium to long term. This means gathering broad information across their local area, and also detailed granular data in areas where there could be childcare shortages, including working with parents to understand exactly how much childcare they are likely to use, their preferences for childcare, and how much they are willing to pay for it.

Support for parents wanting to move into work

Some new demand for wraparound childcare is likely to come from increasing work expectations for parents with primary school aged children claiming Universal Credit. To support parents to be able to make positive choices about work and care, local authorities and Jobcentre Plus should work together to help parents find childcare that enables them to work, and supports local authority teams to understand and meet likely changes in demand. This should also include support for childcare for working parents during the school holidays.

Support to grow the wraparound childcare workforce

To support the growth of the sector, local authorities can help support entry into the wraparound childcare workforce, particularly through supporting childminder entry and leveraging the current start up grant available for childminders. More can also be done to help childminders caring for primary school age children, such as making civic space easily accessible for trips for childminders and supporting childminder networks. Local authorities could also work with education providers in the local area to look at employment routes both during and after study to help expand the wraparound childcare workforce.

Improvements for children with SEND

It is important that the expansion of provision is inclusive for those children with additional needs. This includes both provision within mainstream schools as well as in specialist schools. In relation to specialist schools it will be important to reconcile any expansion of wraparound provision with what can be rigid times with home to school transport. In addition, there needs to be clear guidance for local authorities on how they are expected to address the current shortages for children with SEND, how to meet any additional costs associated with provision and how the extra funding from the Chancellor could be used to meet those costs.

Link to holiday childcare

Many parents need year round childcare, and local authorities have a duty to make sure there is enough childcare for all working parents. Although the additional funding can only be used to support wraparound childcare, there are significant benefits to local authorities in thinking about year round childcare for school age childcare, most notably, that many school age providers need to operate year round in order to be financially sustainable.

Affordability of wraparound childcare

The handbook for local authorities highlights the need for local authorities to raise awareness of both tax free childcare and the childcare element of Universal Credit. This may encourage parents to commit to taking up wraparound childcare places as it might make this more affordable for parents and in turn this may help with sustainability for some providers as more children attend. Local authorities have a positive role in using their own communication channels as well as working with providers to help increase awareness of this support. To make sure the greatest reach, we also think there is a role for central government in backing up the local communication with a national awareness raising campaign.

References

Acknowledgements

Coram Family and Childcare is grateful to the Local Government Association for their support with this report and in particular to Flora Wilkie for her input during the development of the report and comments on the final draft. We would also like to thank the parents and Parent Champions who gave valuable insight into their experience of wraparound childcare and their hopes for expansion.

Thank you also for the input of the sector experts, Victoria Lock, Devoran School, Rebekah Jackson Reece, Out of School Alliance, Lauren Fabianski, Pregnant Then Screwed, Tracy Franklin, Wybers Wood Out of School Club and Jo Pringle, Hempsalls.

Thanks to the local authorities who attended the webinars and to the four local authorities who were interviewed for the case studies, in particular Helen Smith from North Yorkshire, Nicky Hirsch from Islington, Kim Rowntree from Hartlepool, and Samantha Dockrell and Sarah Evans from North Somerset.