As a society, we are facing an array of major global challenges. All these issues play out in a local context and shape our communities and the organisations who serve them.

Why invest in culture?

As a society, we are facing an array of major global challenges.

- The COVID-19 pandemic had a profound effect on individuals, communities, organisations and the delivery of public services. It exacerbated existing inequalities with a particular impact on those who were already most vulnerable.

- The cost of living crisis has affected people and organisations across society, but has only served to deepen the inequalities exposed by the pandemic, with those already experiencing disadvantage more exposed to the impact of inflation.

- The longer terms challenges of climate change have been highlighted in recent years by the impact on communities of extreme weather conditions and underscored by the rising cost of energy affected people’s resilience to these changes.

- All these issues play out in a local context and shape our communities and the organisations who serve them.

Key Facts

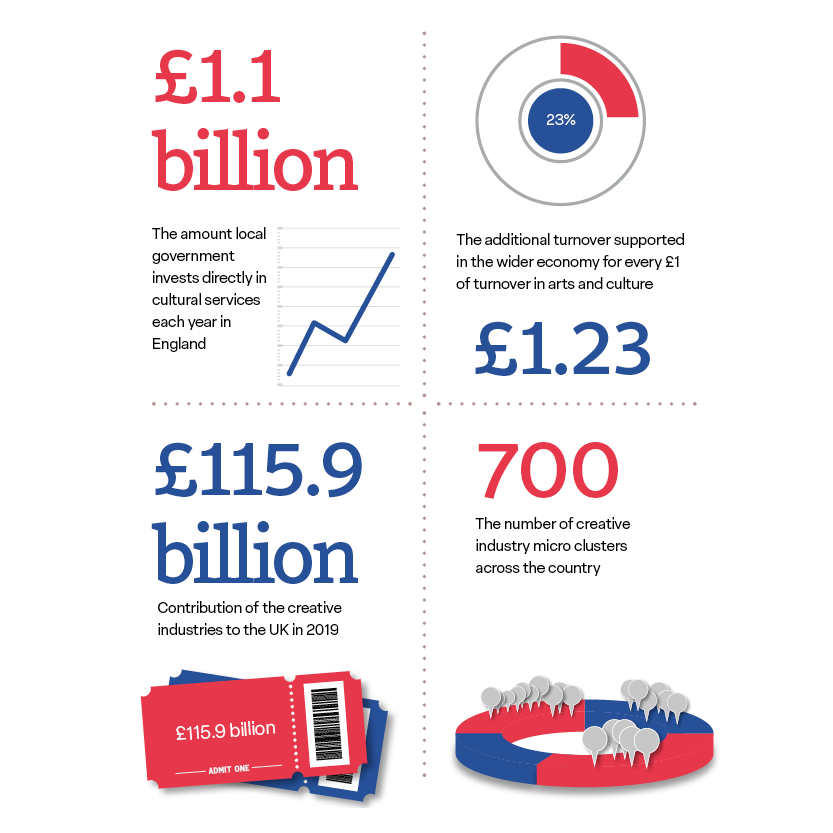

- In 2019, the creative industries contributed £115.9 billion to the UK, accounting for 5.9 per cent of the UK economy and accounted for 2.2 million jobs. They grew at four times the rate of the rest of the economy prior to the pandemic and are geographically dispersed in more than 700 micro clusters across the country.

- Public funding is an essential part of the ecology of the arts and culture in the UK. In 2020, for every £1 generated in the arts and culture, an additional £1.23 gross value added was generated in the wider economy.

- It was estimated in 2015 that Arts Council England’s share of public expenditure was 0.1 per cent but the publicly funded arts contributed 0.4 per cent gross value added.

With so many issues of this scale facing individuals, communities and places, some might question the value of spending money on cultural activity. This report brings together a wide range of evidence to demonstrate why investment in culture is not a luxury, but is essential to our national recovery.

During the pandemic, people turned to culture for solace and connection. There was a vital place-based dimension to this. Local cultural services such as libraries, museums, theatres and arts centres reached out to communities in lockdown to address isolation, support mental wellbeing and provide educational opportunity. The LGA report Leisure Under Lockdown: how culture and leisure services responded to COVID-19 sets out some of the ways cultural organisations supported people, taking their services out to people in the community. It also explores their rapid adaptation to provision of digital provision, and the appetite communities showed for locally produced cultural content.

- Some libraries saw a 600 percent increase in digital membership as well as fourfold increase in the number of ebooks borrowed. Estimates suggest that libraries made 5 million additional digital loans and loaned 3.5 million more ebooks than usual.

- More people engaged with online content. Kingston Library Service reached on average 10,000 people for each of its online Rhyme Time sessions; Norfolk Libraries’ filmed activities were viewed over 172,000 times, and Barnsley Museums’ Facebook page alone had a reach of over 5 million people, with around 500 people a day taking part in online daily challenges.

- Hackney Council’s virtual Windrush Festival had around 3,000 participants.

While the Commission heard evidence on the contribution local culture can make to a wide range of social outcomes, from economic growth to better health and wellbeing, it is critical to note that one of the main reasons to invest in culture is simply that it is important to people. The pandemic highlighted this and it appeared as a constant theme in the evidence presented to the Commission - access to culture and creativity enriches people’s lives.

In this section we will consider each of the four themes we explored as a commission. We sought evidence from cultural services and organisations up and down the country to test the following statements:

- Resilient places. Local publicly funded culture can promote civic pride and change perceptions about a place, contributing to improvements in wider social and economic outcomes.

- Inclusive economic recovery. Local publicly funded culture is essential to our national economic recovery, particularly in relation to the growth of the wider commercial creative economy and in levelling up economic inequalities between regions.

- Social mobility. Local publicly funded culture can help to address educational and skills inequalities and challenges around social mobility.

- Health inequalities. Local publicly funded culture can challenge health inequalities and the impact of loneliness exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic.

For each theme we will set out the key messages the Commission heard, the evidence that local culture has a contribution to make and the specific role the local authority can play.

A literature review for each of these themes can be found on the Commission’s webpages.

1. Resilient places

The Commission heard evidence which explored the following questions:

- Connection to place and ‘civic pride’. What evidence is there that people’s satisfaction in place and quality of life is shaped by the availability of access to cultural activities and engagement? How can investment in culture create more networked, resilient places?

- Place, collaboration and funding. How can we move towards a more strategic long-term and collaborative approach to funding culture at a place-based level? What models are already out there and how can we build on them?

What we heard

- Place underpins the other themes of the Commission. Developing effective place-led strategies for culture will help to deliver a more inclusive economic recovery, promote higher levels of social mobility and address health inequalities. Place and place-making have numerous definitions but identity, heritage, pride in place and community emerge as consistent themes in the literature.

- Councils are the democratic convenors of place. They have a role in providing leadership and partnership brokerage in an area, offering financial resources, democratic legitimacy and understanding of local communities. Councils are funders, investors, supporters and connectors/convenors for culture. They are unique in place because of their breadth of public service delivery.

- Culture and heritage provide the ‘glue’ for place-making and can unlock pride in place, but coproduction with communities is essential in building a shared and inclusive vision for an area.

- Public funding of culture and heritage underpins a much wider creative ecosystem in a place, including everyday creative activity, a thriving civil society and growth in the commercial creative industries.

- Culture-led regeneration initiatives are most effective when they draw on the unique culture and heritage of a place and its communities.

- Collaboration is key. Local strategic partnerships like Cultural Compacts can provide a basis on which to build a shared understanding of culture and place between the council, community, VCS, business partners and wider public sector.

- Civic infrastructure plays an important role in engaging and empowering people and connecting them to others. Well networked communities are an important first step in enabling better community involvement in local decision making.

- Local cultural infrastructure outside urban centres is particularly important in supporting access to cultural participation for young people and others who experience barriers to travelling long distances to access cultural venues and activities.

How does culture contribute to resilient places?

- Culture ‘[helps] people to identify with, understand, appreciate, engage with and feel a sense of ‘belonging’ to their place’, according to the Local Government Association and Chief Leisure and Culture Officers’ Association (CLOA) in their report People, Culture, Place.

- Heritage in particular can be seen as driving up civic pride, Public First’s research found. It also helps with ‘democratisation’ by helping people to realise they can take part and make a difference.

- Social infrastructure is also important. The Arts and Humanities Research Council-funded And Towns research programme identifies that “a vibrant and diverse cultural life grows the creative economy, attracts and retains the young people who can revive depleted town centres, and bridges socially or fractured or divided semi-urban communities.” It aligns this to the need to build civic infrastructure – particularly digital practice and skills. The ‘Feeling towns’ project is looking at new methods and metrics for measuring place and “place attachment” - the emotional bond between people and place – to facilitate better collaborative working on the levelling up agenda.

- In Townscapes, the Bennett Institute argues for the value of “libraries, lidos and leisure centres,” - social infrastructure whose value Kenny and Kelsey argue is poorly understood and wrongly seen in competition with ‘big infrastructure’ projects for resources.

- Creating greater resilience may need some imaginative approaches to funding as the Creative Industries PEC’s industry champions point out. They have called for funders, including central government, to consider how areas that have missed out in the past need support to ensure they get fair access in future.

- The new UK Research and Innovation/Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) Creative Communities research programme aims to build understanding of collaboration, partnership working and the creation of capacity in creative practice at a local level. It will explore the potential for arts and humanities to foster and enable creative communities and capture how collaboration can unlock the full potential of arts and culture. The programme will produce a new dynamic evidence base drawn from across the regions and nations of the UK that will inform future AHRC funding.

- In the Great Place programme, ACE and the NLHF worked together to “enable cultural and community groups to work more closely together and to place heritage at the heart of communities" - an example of this being in Tees Valley, where along with growing economic outputs a key outcome was to grow the shared sense of place and identity

- In Bradford the pride in place that has erupted around the UK City of Culture has been phenomenal. City of Culture has enabled us to have a new narrative that’s been led by the people. This will be the long-lasting legacy for Bradford.

- Culture can be key to improving the economic outlook for a place’s residents. Calderdale Council wants to build pride of place and attract visitors using its tradition of street markets as well as festivals and events, and in Lowestoft, East Suffolk Council is leading work to address a 'culture of disappointment’ through regeneration inspired by the town’s maritime history.

- Big Local is focused on giving people resources and support to do things in their communities over long timeframes – this was cited as an example by stakeholders we spoke to. It is aimed at enabling ‘resilient, dynamic, asset-rich communities’ that are better places to live.

The role of the council

Councils are often seen primarily as funders of cultural services and organisations, but their role is much wider than this. As leaders of place, they can convene cultural partnerships, embed culture in their economic development strategies, engage with wider partners such as health to ensure culture is recognised in wider approaches to community wellbeing and set the context for the growth of the cultural sector and creative industries through their planning, licensing and regeneration strategies. Most importantly, they have a mandate to engage with communities and ensure the voice of local residents is heard in decision making.

South Kesteven’s mental health and wellbeing cross party working group worked in collaboration with health partners, a mental health charity (Don’t Lose Hope) and a community arts provider to investigate whether a local information resource would be useful to help reduce isolation and loneliness post Covid.

A Wellbeing Map was created to provide the wider, still somewhat isolated population with information on local assets and opportunities for participation to bring them back together. Don’t Lose Hope also offered opportunities for people to walk as a group.

On the whole, participants have reported increased engagement and increased personal wellbeing through social interaction as a result of simply taking part and feeling they were helping others.

The project brought groups and organisations together for the first time, all eager to work together for the greater good of their local area. It brought people together in a way that had reduced or no longer existed because of the pandemic.

The Commission heard that councils can play an important role in ‘democratising culture’, and in ensuring greater involvement of communities in the planning, decision-making and delivery that affects them. Co-creation and co-production, though recognised for many years, need greater emphasis, along with ‘doing things with, not to, people’.

Historic England Heritage Action Zones (HAZ)

Historic England’s High Streets HAZ programme and wider HAZ programme is dedicated to bringing buildings back into use, improving streets, training volunteers and engaging new audiences. The associated cultural programme that supports High Streets HAZs focuses on animating town centres, widening engagement and supporting renewed local pride.

Both HAZ programmes are based on strong local partnerships, with councils and community organisations working with national partners from the heritage and culture sectors.

HAZ impacts to date

The first round of the Heritage Action Zone scheme has regenerated 77 historic buildings, helped to remove 13 buildings from the Heritage at Risk Register and brought back into use more than 8,400 square metres (equivalent to 13 large supermarkets) of commercial floor space, boosting local economies.

Supporting economic growth is one of the key aims of the scheme. In Sunderland, two sets of Grade II listed buildings in High Street West have been repaired with new independent shops opening, as well as the creation of a music and culture venue knowns as Pop Recs. The scheme has also led to new housing opportunities. In Nottingham’s Lace Market, the restoration of the Birkin Building has been converted to prime office space for creative industries.

540 community engagement volunteers have been trained, connecting them with their local heritage and helping to increase a sense of local pride and identity. In total, more than 100 community projects have benefitted from the scheme.

The £92 million High Streets-focussed programme is now in year three, with £46.6 million of Historic England funding spent to date.

At the end of year 2 the programme has facilitated the delivery of:

- The repair or conservation of over 560 historic buildings or heritage assets, against a target of 1,800 (31 per cent)

- 101 of 120 construction training activities (84 per cent)

- 2,200 engagement activities

- 311 consultation events

- 114 artworks or installations

- Almost 6,000 sqm of vacant commercial space brought back into use and 2,482 sqm of new commercial floor space created.

Successful projects are being delivered by both council partners in places such as Lincoln and Middlesbrough, and community-focussed groups, such as Heart of Hastings (a Community Interest Company) and Historic Coventry Trust.

The High Streets programme has included the creation of an innovative complementary Cultural Programme in partnership with Arts Council England and the NLHF. This grant strand has brought together cultural groups in many places where they were not previously working together, creating a positive legacy of co-operation and support. These events have animated the high street and created a springboard for new annual celebrations, such as the Oswestry Festival, to continue.

Learning

Experience has shown that there are clear benefits to working with a wider range of partners when engaging in place-based regeneration. Place-based regeneration has the greatest chance of success if it can galvanise local stakeholders to a common purpose.

2. Inclusive economic recovery

Evidence presented to the Commission explored the following questions:

- High streets. How can local publicly funded cultural services and organisations bring life back to high streets and town centres, where an existing decline in retail has been aggravated by the pandemic and a change in working patterns has affected office occupancy and footfall in town centres?

- Public funding and the creative industries. In the context of the new sector vision for the creative industries, what role does publicly funded culture play in supporting growth in the wider creative industries, particularly in areas identified as priorities for ‘levelling up’?

- Cultural regeneration. What evidence is there that investment in cultural regeneration programmes can change perceptions about place and contribute to sustainable and inclusive economic growth?

What we heard

The cultural sector has a significant role to play in growing local economies and supporting an inclusive recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic, in particular in relation to supporting high street and culture-led recovery of town centres.

- The pandemic (and subsequent rising cost of living) has exacerbated existing economic inequalities in our society. We have an opportunity to pursue an inclusive economic recovery with the aim of reducing inequalities and growing shared prosperity, cultural democracy, aspiration and social capital. An inclusive approach to setting a cultural recovery plan (that is, enabling and encouraging communities to feel included, listening to and working with them) is facilitated by open decision making, co-creation, and co-production with cultural organisations and the communities they serve. Listening to a diverse range of voices in establishing and delivering these plans is key to making recovery inclusive and sustainable.

- Local cultural organisations such as libraries, museums and arts centres are trusted spaces and therefore key to supporting inclusive recovery. Councils can work with cultural organisations to bring together people with a wide range of experiences and ideas to consider what inclusive economic recovery means to them.

- Culture can help to shift perceptions about a place. Arts Council England describes how culture-led regeneration “[Helps] to attract skilled people and business investment by enhancing the image of areas as places to live and work” but that it also stimulates jobs, attracts visitors and boosts local businesses.

- Cloning doesn’t work: When it comes to addressing regional and local social and economic inequalities, the ‘cloning’ of places doesn’t work. A local and specific approach which draws on the distinctive culture and heritage of an area is needed to ensure approaches to regenerating places and addressing regional inequalities are inclusive of communities and authentic to a place. People want to feel their place is unique and places that succeed in reinvention are likely to have a clear picture of the connection between the past and the future.

- Heritage-led regeneration initiatives can provide a model for a sustainable approach to local economic development, as set out in Historic England’s body of tools and best practice on Heritage and Sustainable Growth.

- Economic renewal of town centres. As we see the pandemic and subsequent change in working patterns exacerbating an existing decline in high street retail, the experiential offer on the high street becomes more important. Local publicly funded culture can play an important role as part of a wider offer that includes leisure and hospitality. According to the Arts Council England’s research, half of adults (50 per cent) would like to see more cultural experiences on their high streets. This 50 per cent rises to 54 percent among those aged 25 to 34 years of age and 57 per cent among black Britons.

- Stronger partnerships between councils, cultural organisations and creative businesses can support economic growth, as illustrated by Kent County Council’s work with the Backstage Academy and their strategy for supporting the creative industries.

- To build a truly inclusive approach to recovery, it is essential to address issues of low levels of diversity in the audience, workforce and leadership of cultural services and organisations. This is a complex and multifaceted issue, but it is clear that councils can provide a leadership role. The priority they give to increasing diversity in local strategies, their approach to community engagement and the voices they listen to, their championing of diversity initiatives and their use of procurement and grant making can all influence this agenda. The Commission heard that the representation of a greater diversity of voices, particularly in relation to race, class and disability in establishing local plans for recovery would help to generate strategies that were more authentic to a local area and which had higher levels of community buy-in.

Examples of projects focused on diversifying high streets and town centres:

- Barnsley Glass Works – the council repurposed empty units in a new shopping centre so that it appeared full and would attract new retailers, and gave visitors reasons other than shopping to come into the space.

- Kirklees Cultural Heart – art and cultural partnership projects filled empty market stalls and then shopping units, creating more footfall to shopping areas and encouraging secondary spend.

- Plymouth Culture, in partnership with Plymouth City Council and Plymouth City Centre Company Business Improvement District, developed a programme of taking on empty units and activating them as spaces for creative and cultural projects to drive footfall back to a reimagined high street. Projects supported include a climate hub in a four-floor former bookshop and Bike Space, a local not-for-profit social enterprise offering last mile delivery.

- Weston-super-Mare – heritage action zones have been used to revitalise the town centre. Alongside physical improvements, there is a cultural programme building on Weston’s thriving creative scene, engaging people with the town’s heritage and looking ahead to its future.

- Lancaster City Council – the council are engaging in a transformational development of The Canal Quarter to embrace the area’s existing heritage alongside contemporary development, creating a diverse residential, commercial, cultural, and recreational neighbourhood.

How does culture contribute to economic growth?

There is a growing body of research into the relationships between culture, the creative industries and economic growth. The Commission heard evidence that the publicly funded cultural services and organisations are closely allied to growth in other areas of the economy including the commercial creative industries and the visitor and night-time economies.

The relationship between local publicly funded culture and the commercial creative industries is complex and interdependent.

- The creative industries contributed £115.9 billion to the UK in 2019, accounting for 5.9 per cent of the UK economy. In the year from October 2019 to September 2020 the Creative Industries accounted for 2.2 million jobs (DCMS 2021). They grew at four times the rate of the rest of the economy prior to the pandemic and are geographically dispersed in more than 700 micro clusters across the country. As such they are an important driver of our national economic recovery and levelling up.

- But the Commission heard that the long-term sustainability of the creative industries cannot be delivered without public funding of culture, which underpins the development of the wider creative sector. As the 2007 Demos report Publicly Funded Culture and the Creative Industries sets out, there is ‘symbiosis’ between publicly funded arts and the creative industries, for example between the performing arts and the film and TV industries or the commercial stage, particularly in relation to the development of a talent pipeline. The publicly funded cultural sector provides incubation space for the development of creative practitioners and can support them through local supply chains. The Work Foundation and Nesta’s influential report Staying ahead: the economic performance of the UK’s creative industries also highlighted a growing recognition of “the subtle but important linkages between the vitality of the creative core, the creative industries beyond and creativity in the wider economy”.

- A vibrant cultural environment creates places where people want to relocate their businesses and workforce. More recently Creative Industries PEC researchCreative Industries PEC research into the relationship between larger publicly funded institutions and the growth of creative clusters found that representatives from creative industry businesses reported that the presence of larger anchor cultural institutions supported the character of their local area and made it a more attractive place to visit and work. More research is needed to unpick the complexities of how a thriving local publicly funded cultural ecosystem and the wider historic and cultural environment influence the growth of commercial creative clusters. The Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) has an important role to play in funding this type of research, for example through their support for the Creative Industries PEC and their new Creative Communities programme.

- There is an opportunity to build on existing models for cultural cluster development (for example, the innovative approaches to cultural development zones developed by the Greater London, Greater Manchester and North of Tyne Combined Authorities) to provide incentives and support for the growth of local creative industry clusters and micro clusters, as explored in a recent report on Creative Improvement Districts by Culture Commons (2022).

Culture can underpin growth in other sectors and is particularly important to the visitor and night-time economies.

- Culture is essential in driving a healthy visitor economy. The visitor economy is one of this country's strongest performing sectors. Culture, and particularly heritage and the historic environment, is a key draw for most visitors. At least 40 percent of all tourists worldwide can be considered cultural tourists. Cultural tourists provide more economic benefits because they tend to stay longer than other tourists. At the same time, cultural institutions need visitors to provide the spend that makes cultural institutions more viable. The Commission heard that in areas reliant on the visitor economy, culture can help to extend the season, encourage visitors to stay longer and return to places.

- Recent research by Visit Britain has underlined the fundamental relationship between culture and ‘Brand Britain’: culture and particularly heritage is the main driver of the majority of inbound visits and the basis of Britain’s reputation overseas as “a place where history meets modernity and a range of sites and (‘must-see’) experiences are offered within easy access”.

- Local economic growth goes hand-in-hand with an inclusive approach and conversely can be held back by a failure to deliver on this agenda. For example Visit Britain has calculated that the Purple Pound (the spending power of disabled households) is worth £15.3 billion to the British visitor economy. However, it has also been calculated that businesses lose £2 billion a month by ignoring the needs of disabled people. Councils and the cultural sector can help to address this by embracing #WeShallNotBeRemoved’s Seven Inclusive Principles for recovery.

Examples of cultural programmes underpinning the visitor economy include:

- Hull, where UK City of Culture has proved a catalyst for tourism.

- Coventry, where the UK’s first immersive digital arts gallery is a tangible legacy of the UK City of Culture year.

- Portsmouth City Council, which invested in heritage attractions to bring more visitors to the city, linked to enhanced leisure and retail.

- Thanet, where Turner Contemporary and Dreamland have boosted the visitor economy – visitors up 19 percent between 2013 and 2015 and an extra £47 million into the local economy, helped by leadership and investment from Thanet District Council and Kent County Council.

- Wrexham County Borough Council, which is planning its own ‘year of culture’ following its bid to become UK City of Culture 2025. Wrexham, which was granted city status as part of the Queen’s Platinum Jubilee celebrations, has raised its profile and demonstrated how much it has to offer – including attractions like the Racecourse Ground, the home of Wrexham AFC.

- Forest of Dean District Council, which has extended its partnership with Forest of Dean and Wye Valley Tourism to showcase the best of what the area has to offer. They have run a number of campaigns, such as ‘Find your Freedom’ which highlighted craft, sport, food, and heritage activities in the local area.

The role of the council

The council plays an important role in setting the context for a thriving cultural sector connected to the wider creative and visitor economies. In the first instance they can bring local organisations with a stake in the cultural sector together to establish a cultural strategy for an area. The Commission heard in evidence from UK City of Culture applicants and other programmes including High Street Heritage Action Zones, that bringing a range of partners together around a shared cultural/heritage strategy has the power to galvanise support for culture and create forward momentum.

The council’s role in strategy setting also puts it in a unique position to influence the inclusion of culture in other important local and regional strategies, including those dealing with the visitor economy and wider plans for economic development developed through the local economic partnership or combined authority.

Councils and combined authorities have a role in supporting the commercial creative industries and setting the context in which they can grow through their wider planning, strategy setting and regulatory role. Establishing culture as a priority in economic development strategies, developing cultural partnerships and investing in public cultural infrastructure can support the development of creative clusters. The LGA’s report Creative Places, offers a guide to councils seeking to support their local creative economy, while their report on the combined authorities and the creative industries explores the ways in which these authorities are prioritising culture at a regional level.

Specific programmes of culture-led regeneration coordinated by the council have the potential to support better local cultural infrastructure, engage communities with local culture and heritage, and re-brand the image of an area. Stakeholders told us that in order to produce the most transformative and sustainable changes, it was vital for councils and combined authorities to engage local people and to give them and their representatives agency in establishing and delivering regeneration plans.

Councils are also key to the delivery of the ‘inclusive’ aspects of ‘inclusive economic recovery through their place shaping role in cultural services. For example, libraries tend to reach into all parts of the community. Business support and skills programmes routed through libraries appear to be particularly effective at reaching groups not normally accessing other options, as we have seen with the British Library Business and IP Centres.

Reading Borough Council: Oxford Road, Reading: Re-imagining the High Street Through Your Stories

Historic England offered several Pilot Grants to the HSHAZ schemes to initiate and test projects to engage communities, during the Covid pandemic, in September 2020. Reading was successful in achieving a grant of £9,231 to run a pilot project for the HSHAZ. This pilot project: Re-imagining the high street through your stories focused on the Oxford Road conservation area. The project engaged the community, to explore people’s real stories of Oxford Road and to link them with their local heritage and rich multicultural history.

During the community engagement phase, many residents told the council that they would like to see unsightly areas such as hoardings brightened up and see modern artwork that reflected and celebrated the Oxford Road area positively. A series of art pieces celebrating the history, heritage and vibrancy of culture of the area were created, including:

- Welcome to Oxford Road Mural by AZUCIT The council commissioned local graffiti artist Arron Lowe (AZUCIT) to create a ‘Welcome to Oxford Road’ mural on a large hoarding.

- Caroline Streatfield – Hidden Recipes from the Ancestral Home Local artist Caroline Streatfield produced a set of 17 recipe cards showcasing family recipes, which can all be cooked using local ingredients.

- Baker Street Productions developed a multi-sensory, three-dimensional tour of the Oxford Road, creating an engaging narrative through which participants explore the heritage of the buildings and people. Gemma Anusa – Through your eyes.

- Gemma Anusa, a local artist and Oxford Road resident, has created two paintings that have been digitised and attached to railings along the Oxford Road. They feature two faces that are depicted with a gradient skin tone from white to black to represent the multicultural community.

Following the successful pilot, in December 2021, Reading was awarded a £85,000 grant to develop a programme of activities and events to celebrate their local character and heritage, making our high streets a key place to experience and participate in culture and heritage. The programme will include active participation and support of the project Cultural Consortium, whose membership comprises well-established local cultural organisations such as Reading Festival’s Partnership Group, Reading Cultural Education Partnership and the University of Reading.

4. Health inequalities

Evidence presented to the Commission responded to the following questions:

- Mental health. How can locally funded cultural activity support greater social connection and engagement and help to address rising levels of mental ill health exacerbated by the pandemic?

- Health and wellbeing in children and young people. How can locally funded cultural services and organisations specifically support children whose mental wellbeing has been affected by the pandemic?

- Isolation. How can locally funded cultural services and organisations help to reconnect those who have suffered from isolation during the pandemic, particularly in relation to the clinically vulnerable?

What we heard

- Different groups experienced the pandemic differently. For example, The Office for National Statistics (ONS) breakdown of deaths involving COVID-19 show that disabled people made up 59.5 per cent of all deaths for the period to July 2020, whilst only 16 per cent of the UK population are disabled. Research carried out by Public Health England in 2020, prior to the launch of the COVID-19 vaccination campaign revealed that people of Bangladeshi ethnicity had twice the risk of death compared to people with white British ethnicity, while people of Chinese, Indian, Pakistani, other Asian, Caribbean and other black ethnicity had 10-50 per cent higher risk of death than people of white British ethnicity. Inequalities also mapped to geography. There was higher mortality in the north compared to other regions of England (204.1 to 174.4 per 100,000), according to the Northern Health Services Alliance. The devastating impact of the pandemic and its disproportionate impact on people living in areas of high deprivation, people from ethnic minority backgrounds and their communities, on older people, those with a learning disability and others with protected characteristics has accelerated the urgency to address the health inequalities in our society, as set out in the NHS Equality and Health Inequalities Hub.

- Publicly funded arts and cultural services made enormous contributions to our daily lives and wellbeing during the COVID-19 restrictions. They have a role to play in supporting health at various levels in society, from contributing to general wellbeing across a population, to helping to prevent specific forms of ill health and providing treatment for acute health conditions (see the Power of Music report). The challenge now is to ensure that the value of arts and culture continues to be recognised during the post COVID recovery period, and benefits from publicly funded investment and support, drawing on the significant evidence and recommendations from 2017 Creative Health report.

- The pandemic has had a large and negative impact on the nation’s mental health as outlined in this What Works Wellbeing briefing. One in eight adults (12.9 per cent) developed moderate to severe depressive symptoms during the pandemic. Again, the effects of this were not evenly distributed. The Kooth project in particular reports that increases in poor mental health was 19 percent higher in young people from black, Asian and minority ethnic backgrounds than their white peers.

- During the pandemic, cultural services and organisations adapted rapidly by bringing services online. The Commission heard that for those audiences who find it difficult to access in-person activities and programmes due to physical or geographical barriers, this represented a new quality of access to cultural provision. However, it was also acknowledged that the digital divide creates barriers to online consumption for other vulnerable groups, alongside those who experience poor connectivity related to geography. There is a need for a balance between resumption of face-to-face provision with the continuing development of digital offers, but this places a strain on already pressured budgets and staff capacity. Libraries in particular face financial challenges in meeting the continued demand for e-books, which cost more than physical copies.

- The pandemic also fostered a greater public appreciation of the wider environmental determinants of health and the role a strong cultural infrastructure, including public spaces for cultural engagement such as parks and the historic environment can play in supporting healthy communities. Inequalities of provision here echoed the wider health inequalities exacerbated by COVID-19. The development of Integrated Care Systems may represent an opportunity to build culture and creativity into future plans for health and social care.

- Tackling Loneliness: The world’s first government Strategy for Tackling Loneliness was launched in October 2018. It recognises loneliness as a pressing public health issue, and continues to guide coordinated cross-government action to make this country a place where we can all have strong social relationships. Increasingly, areas are developing their own local strategies to tackle loneliness, taking a place-based approach to improving social connections. There is an opportunity here for cultural organisations to play a key role in bringing communities together and tackling loneliness.

- Access to cultural opportunity is not a fixed point. Being inclusive requires individuals and organisations to commit to continuous improvement, regularly training staff to improve understanding of inclusivity and referring to organisations leading practice in relation to access, for example Inclusion London’s materials relating to the social model of disability. The Seven Principles for an inclusive recovery offer helpful guidelines for navigating a return to delivery on the part of cultural services and organisations. The National Lottery Heritage funded VocalEyes report Heritage Access 2022 Report and Benchmarking Tool provides practical guidance for cultural sector organisations to improve the quality of information they provide to people with disabilities, to better support accessibility both online and on site.

- Social prescribing is seen as one means of enhancing wellbeing by connecting health and cultural services. Long-term investment in social prescribing has been welcomed by the sector, but there are gaps in understanding the barriers and enablers for health and care professionals when engaging in social prescribing for patients. Models for funding activity associated with prescribing need further development to maintain service delivery and minimise risk to both providers and patients, particularly in the case of community sector provision. Cultural provision should not be seen as a replacement for care. It should instead exist hand in hand with health services, with a shared understanding of the role and contribution of cultural stakeholders. There should be a distinction between the implicit and explicit health benefits of culture, to ensure that those who are working towards explicit health outcomes have the correct support, supervision, and skill development in place. to ensure that those who are working towards explicit health outcomes have the correct support, supervision, and skill development in place.

Examples of work with children and young people include:

How does culture contribute to addressing health inequalities?

Arts and cultural activities have an important role to play in improving mental health and supporting wider wellbeing. The Creative Health report from the APPG on Culture, Health and Wellbeing remains relevant and provides a robust evidence base on the contribution of culture to health, but its findings have not been embedded everywhere.

There is a significant and growing literature on the relationship between health and culture. The Commission heard that the benefits of cultural activity will depend on the type of health/wellbeing intervention required.

- Cultural programmes have been shown to have specific benefits in clinical treatment of conditions such as dementia and depression, as outlined in UK Music and Music for Dementia’s report The Power of Music.

- Cultural programmes targeted towards at risk groups are also valuable in supporting a preventative approach to mental ill health and loneliness, for example Helix Arts who ran the Better Connected Project in Tyneside, to improve the mental health of 350 carers through arts and cultural activities.

- More broadly, good cultural infrastructure and universal provision of cultural services at a population level has been shown to be beneficial to community wellbeing, promoting networked resilient communities. Engagement in cultural activity can play an important role in addressing issues of loneliness, exacerbated by the pandemic.

It is important to note that economic growth and enhanced wellbeing are closely intertwined and are not separate competing objectives. Wellbeing has been shown to be linked to higher levels of productivity.

Examples of projects combatting social isolation include:

- Norfolk’s Healthy Libraries Scheme has played a vital role in maintaining connections in a largely rural county, through a range of activities from singing and colouring groups to a reading project aimed at people who are housebound.

- Heritage Doncaster’s History, Health and Happiness which seeks to tackle isolation and improve wellbeing using museum collections as the basis for outreach and community engagement.

- HenPower which engages older people in more than 40 care homes with arts activities.

- Entelechy Arts, who delivered Creativity at Home in Lewisham, sending creative and arts activities to people’s homes.

- Culture Liverpool whose new community programme is designed to slowly re-introduce culture to clinically extremely vulnerable people, those who have experienced mental health challenges, bereavement or financial hardship.

- Surrey County Council have created Death Cafés in Surrey Libraries to act as centres for bereavement support, to help tackle isolation – particularly among the elderly.

- Tyne and Wear Museums and Archives set up Radio Chopwell, an innovative partnership project to empower the community of Chopwell, Gateshead to collect and share digital sound that interpreted theirs lives and community and create a regular online radio broadcast and in-person social events to showcases the lives and work of Chopwell residents.

The role of the council

Council services often support the most vulnerable in society, whether it is libraries offering computer access and training to those experiencing digital exclusion, museums providing ‘warm banks’ to those who cannot heat their homes or targeted cultural activity offering socially-prescribed services for those experiencing mental illness or loneliness.

These services offer a gateway to wider forms of cultural engagement and in many cases provide free access to all to the benefits of culture and heritage. As we have seen though, access to culture is still unequal and councils have an important role to play in opening up services to all sections of their community by making sure they meet access standards and by working with under-represented groups to ensure their voice is heard in shaping service and programme delivery.

Councils also offer a place-shaping function beyond delivery of specific services. Local authorities sit at the interface of the relationship between culture and health and are crucial in building collaboration between the cultural sector and public health, social care and the NHS.

Examples of publicly funded projects which connect people with arts and culture to improve mental health include:

- Books on Prescription services are available in a number of libraries across England including the Reading Well booklists.

- As part of their social prescribing service, Shropshire Libraries have experienced advisors who can talk about the services and resources available in the libraries. Shropshire also has the Designs in Mind studio which support adults with mental health issues and delivers high quality and experimental art and design work. Disability Arts in Shropshire also provided mentoring and funding advice to disabled visual artists.

- Suffolk Libraries provide a dedicated wellbeing service, providing drop-ins, reading lists and links to other resources.

- London Arts and Health, a member organisation including ACE, the Culture, Health & Wellbeing Alliance and Greater London Authority, supports artists and health professionals to extend the reach of the arts to communities and individuals.

- Manchester Camerata's Music in Mind programme which uses improvisation to help people living with dementia to express themselves and communicate with others.

5. Conclusion

Culture has a significant role to play in helping places to recover from the pandemic and in supporting local communities as we face new challenges. Culture, library and heritage services can:

- build civic pride in place

- promote better health and wellbeing, particularly addressing challenges of loneliness, isolation and mental ill health arising from the pandemic

- support local economic growth, including revitalising high streets, underpinning growth in the commercial creative industries and the wider development of the visitor and night-time economies

- encourage social mobility by ensuring access for all to local cultural opportunity and providing routes into the rapidly growing creative industries.

Bev.g.star's story

bev.g.star: Community Artist, Weston-Super-Mare

“I grew up on the council estates of Weston. I didn’t know there was anything outside them. There were some beautiful days, but it was grey, blockwood, closed. But now I see the light, colour and beauty.”

bev.g.star is one of a new generation of successful community artists in Weston-Super-Mare. She has received commissions from Culture Weston as part of Weston’s Heritage Action Zone and from Terrestrial, an arts production collective for projects. Bev also works with members of the community to help them develop their creativity and use art to support recovery from mental illness and substance addiction.

While recovering from acute depression and anxiety, bev started a creative project called ‘Humans of Weston’ (HOW). HOW is an online journalistic platform which provides ‘a beautiful insight to the colorful Humans of Weston’.

This work led to bev being invited to feature a spray jam on Birnbeck Pier, a collective spray-painting event for artists. This event is what inspired her to take up painting and public art projects. The Town Council gave permission for the first spray jam, and subsequent jams were supported with grants from the local authority. They are now a popular regular event and bev.g.star is at every one of them.

“They say that Banksy is the person who brought the art scene to Weston. But we were always here. He was the one who made the council see what could happen.”

In 2018 Terrestrial received funding from Arts Council England, Jerwood Arts and North Somerset Council to work with the community and local artists in Weston. Together they set up Weston Artspace which was given permission to occupy a property on the high street rent free for one year. Weston Artspace is now at the heart of Weston’s creative and cultural landscape and is a space which was pivotal to bev’s development as an artist.

“I didn’t realise there were so many of us. I’d been walking around kicking the floor, wishing for an opportunity. I was that person without any friends, looking for people like me, and then suddenly there they were, and the opportunities started happening. It was amazing.”

Culture Weston, a new community arts partnership led by Theatre Orchard, is now based at Weston Artspace. It has supported festivals and events and oversees the development of the 21st Century Super Shrines project in partnership with the community and local artists like bev. This project is part of the four-year long High Streets Heritage Action Zones’ Cultural Programme, funded by Historic England, in partnership with Arts Council England and the National Lottery Heritage Fund. The project, launched in May 2021, is designed to inject vibrancy and colour into Weston’s high street and shine a spotlight on the local community in a number of creative events, including a new window exhibition and YouTube series.

“I didn’t even know I could be an artist. Now I’m one of Weston’s artists that focus on contributing to the community. I’ve never been this busy and able to be creative. It feels like a reward for all the adversity, trauma and negativity I’ve had. I’m living my best life.”