This report covers the work PAS have done on what can we learn from the current challenges and opportunities in Environmental Assessment practises to inform the development of Environmental Outcome Reports (EOR)

What are the barriers and challenges in undertaking Environmental Assessment?

In 2022 PAS, jointly with DLUHC, held a series of workshops to gather views from councils on the current challenges of undertaking Sustainability Appraisals, Strategic Environmental Assessments and Environment Impact Assessments. The workshops looked at what can we learn from the current systems challenges and opportunities to inform the development of EOR.

There are known issues with the current SA/SEA/EIA system, such as

- Too much paperwork generated and an overly cautious approach to assessing impacts

- A lack of access to robust and consistent data

- Assessments, particularly at the project level, can be inaccurate and misleading with the scientific uncertainty or implementation being often downplayed

- A lack of monitoring of the forecasted impacts or mitigation, with many proposed mitigation measures either not being implemented as proposed or being ineffective.

The five workshops covered an overview of the new EOR system as set out in The Levelling Up and Regeneration Bill and a series of deeper dives into some of the more technical aspects of the current system such as screening and scoping stages as well as assessment, monitoring and remediation stages of EIA and SA/SEA.

The views and intelligence gathered during this work has been used to produce an Environmental Assessment Barriers Report, You can download a copy here or read this webpage.

Project background and scope

This project is part of a wider programme of work to support the emergence of the Government’s Environmental Outcome Reports (EOR) and Environmental Assessment regime. The Levelling Up and Regeneration Bill , plus the accompanying policy paper produced by Department of Levelling Up, Housing & Communities (DLUHC), launched a new form of environmental assessment known as Environmental Outcome Reports (EOR). The intention is that Environmental Outcome Reports will replace the existing system of Sustainability Appraisals (SA), Strategic Environmental Assessments (SEA) and Environmental Impact Assessments (EIA).

The full details of how EORs will work is at present unknown and The Levelling Up and Regeneration Bill introduced broad powers allowing new regulations and guidance to come forward and signalling future consultations. What we do know is that the intention is to make EORs simpler, using more consistent data and focussed on measuring environmental effects against improving environmental outcomes.

It provides the views from local authorities, along with some recommendations and ideas for how the regime might resolve some of the existing barriers & challenges within the current Sustainability Appraisal (SA), Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) and Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) & Environmental Statements (ES) policy regime. The report is to inform Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities (DLUHC) as they consider ways to develop the emerging approaches to environmental assessment. It was written by PAS facilitators and shared with participants for their comment.

This report and its content require a level of assumed knowledge about the environmental assessment regime and its terminology.

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to the people who volunteered their time and careful thoughts. The officers provided their own opinions that were not necessarily those of their employers.

Participants came from a wide variety of local authorities, including from Thurrock District Council, Medway Council, Hartlepool Borough Council, Bassetlaw Council, North East Lincolnshire Council, Surrey County Council, Birmingham City Council, Stockport Metropolitan Borough Council, Hambleton District Council, Gedling Borough Council, Cornwall Council, Cheshire East Council, Broadland and South Norfolk Councils, Plymouth City Council, Harborough District Council, East Suffolk Council, Peterborough City Council, Castlepoint Council, Tees Valley Council, Central Bedfordshire Council, Braintree District Council, Wiltshire Council, St Helens Borough Council, Norfolk Council, Wealden Borough Council, Stafford District Council, Royal Borough of Windsor and Maidenhead Council, South Kesteven Council, Reigate and Banstead Borough Council, Nottingham City Council, South Lakeland Council, Telford Borough Council, Enfield Council, Hinkley and Bosworth Borough Council, North Devon Council, London Borough of Barnet Council, Eden District Council and Walsall Council.

Methodology

Between June and July 2022 PAS held a series of workshops with officers from local authorities to explore their recent experiences with the current environmental assessment regime. Sixty-seven councils participated in the workshop series. Participants were a range of professional officers including development management, policy, environmental specialists, and were from a varied range of councils small to big, district to county. This report is intended to set out a consensus view across this mix of authorities and officers.

The workshop series kicked off with an overview session where the participants were asked general questions to enable a discussion to commence and to help frame the direction of the project. The questions were around the thinking behind how EOR might work and, importantly, investigating the ‘fixes’ needed in the current environmental assessment policy regime of Sustainability Appraisal, Strategic Environmental Assessment and Environmental Impact Assessment.

There then followed four deepdive workshops which were in smaller officer groups to develop the issues, including those raised at the initial workshop. The smaller deepdive workshops were focussed on the following stages of the current environmental assessment policy regime.

- EIA – Screening and Scoping

- EIA – Reviewing, monitoring and remediation

- SA/SEA – Assessment (including accessing data)

- SA/SEA – Mitigation, monitoring and remediation

The format of all the workshops was split into three separate chunks, firstly a presentation by DLUHC tailored to the event’s focus followed by a Q&A session facilitated by PAS. This allowed participants the opportunity to ask DLUHC any queries and acted as a thinking warm-up for the breakout rooms. The breakout rooms were used to run a workshop session that provided the opportunity for discussion between participants in smaller groups and enabled contributions & ideas on key topics.

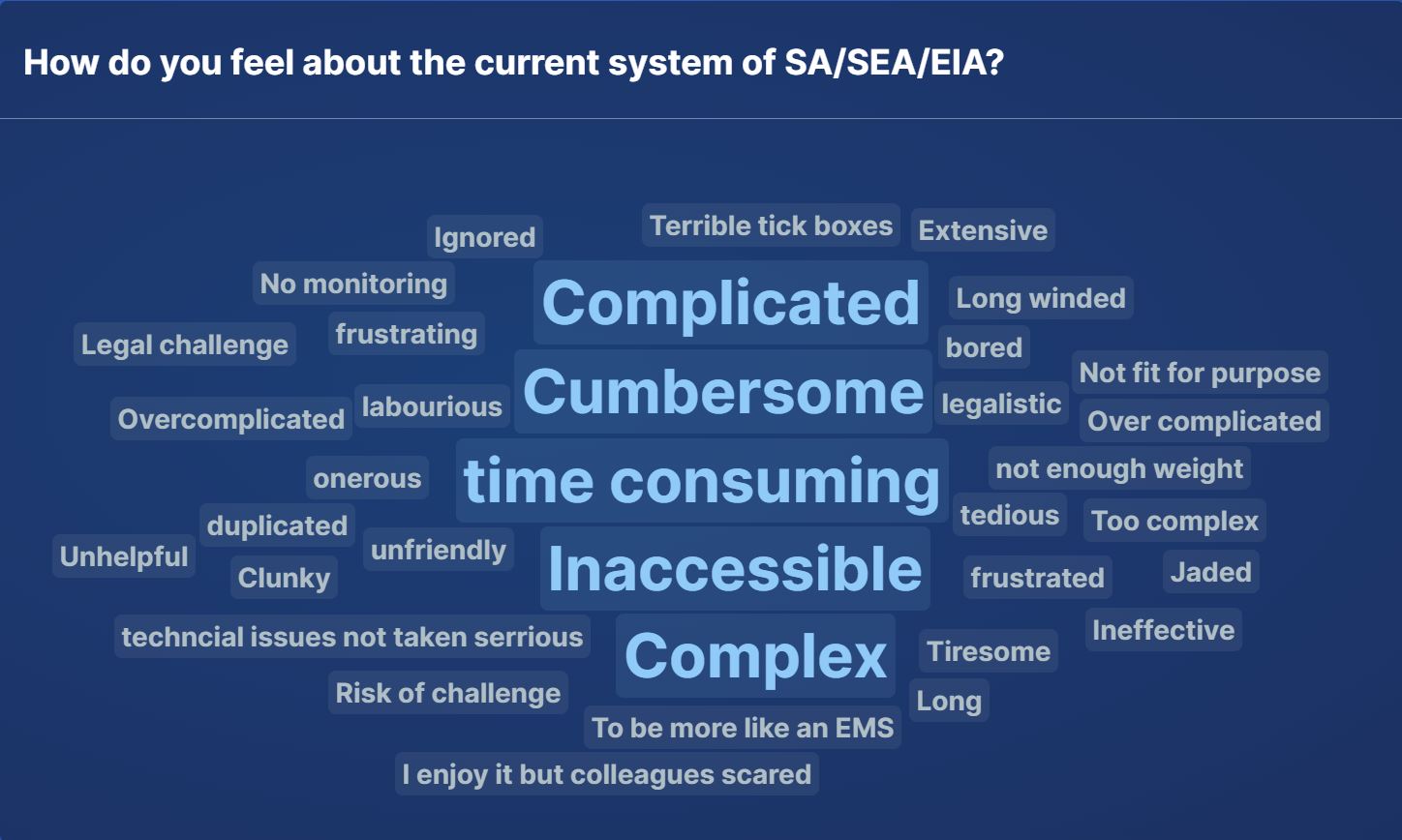

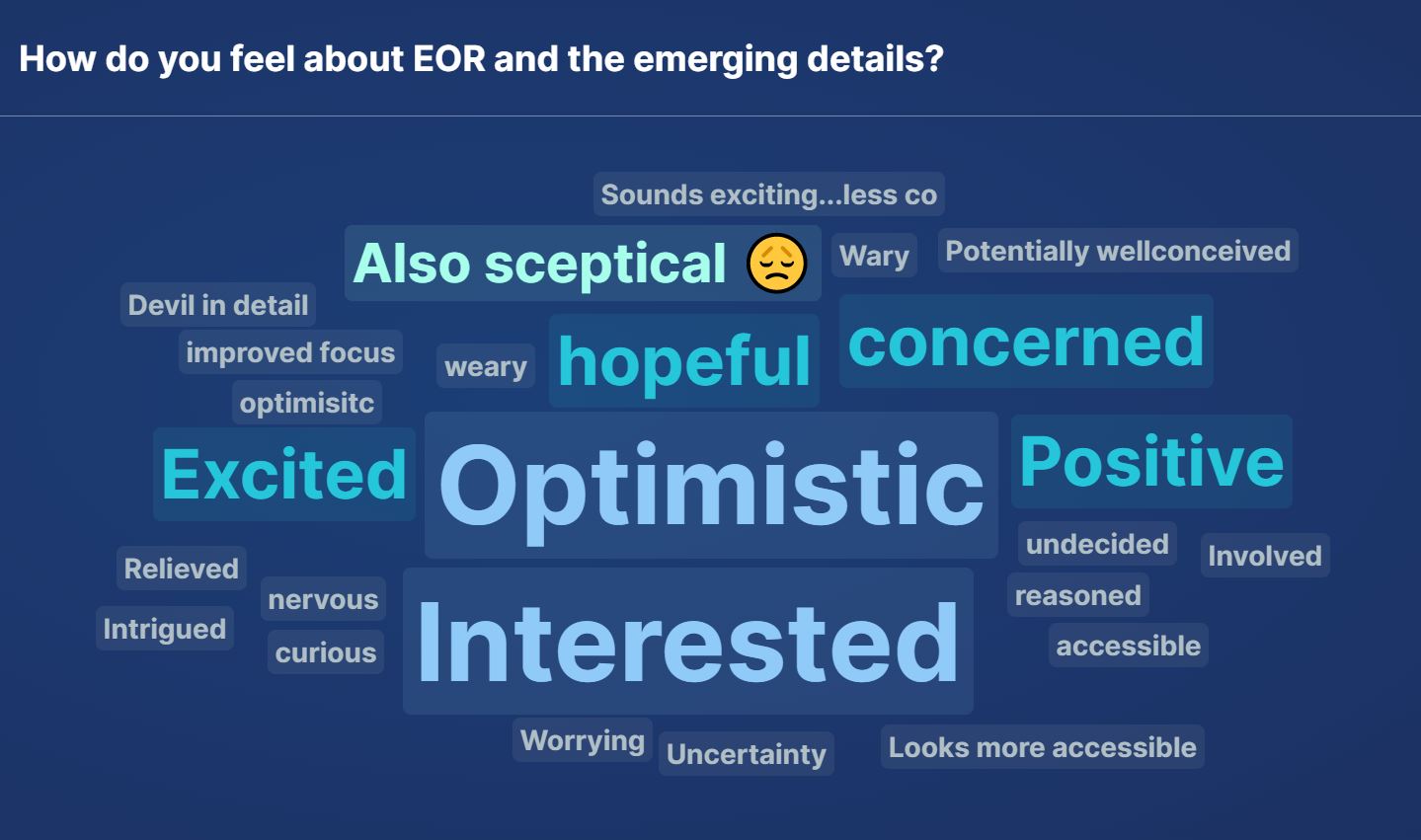

During the overview workshop participants were asked to create two wordclouds to reflect their feelings on the current system of environmental assessment and the emerging Environmental Outcomes Reports.

In both the overview and deepdive workshops participants were asked to consider the fundamental question ‘What needs fixing in the current environmental assessment policy regime?’ accompanied by more probing questions around a number of themes:

Confidence

-

How confident do you feel in engaging with the process?

Engagement

-

How much do politicians/communities/others engage?

-

Do you get support from consultees in time? What are the issues here?

Questions particularly around Environmental Impact Assessment

-

For Screening and Scoping requests is the information submitted sufficient and pitched at the right level?

-

How much is spin?

-

Is uncertainty transparent?

-

How much monitoring, enforcement and remediation is undertaken?

Questions particularly around Sustainability Appraisals and Strategic Environmental Assessment

-

How effective do you find the process?

-

Does framework scoping and setting indicators work?

-

How is uncertainty dealt with, is it transparent?

-

Where is the value for plan making?

-

What are the main data gaps? Are effects quantified accurately?

-

How much monitoring, enforcement and remediation is undertaken?

-

What are the impacts on costs and resources? Is there a reliance on external consultants?

Workshop series follow-up

Following the workshop series participants were provided with the opportunity to comment and reflect upon a draft version of this report. Approximately ten local authorities provided thoughts and opinions on the draft report via email and using Slido engagement tool.

The workshop series also gave rise to PAS establishing an Environmental Officer Group made up of participants who showed an interest in continuing dialog with PAS on environmental assessment. The Environmental Officer Group has representatives from Surrey County Council, Birmingham City Council, Stockport Metropolitan Borough Council, Hambleton District Council, Gedling Borough Council, Cornwall Council, Cheshire East Council, Broadland and South Norfolk Councils, Plymouth City Council, Harborough District Council and East Suffolk Council.

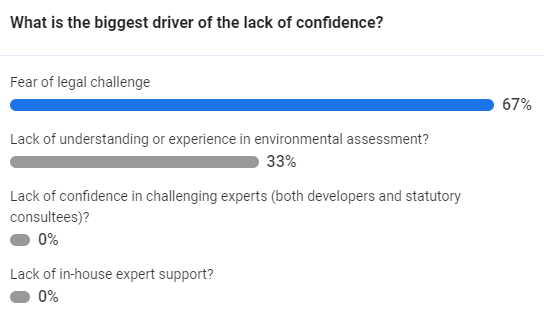

Finally, there was a workshop with the Environmental Officer Group to ensure that PAS had properly understood the issues raised and to consider possible recommendations in finalising the report. This workshop was held in September and used Slido engagement tool to gather feedback. The results of the Slido poll exercise can be found at Appendix A.

For the workshop series and follow up feedback gathering all opinions were provided in a “Chatham House” environment with no opinions being attributed to any one individual. Support or otherwise of a viewpoint was expressed verbally through the series of workshops or comments on the draft report.

All points raised in this report have been triangulated across the workshop series and are reported as a consensus viewpoint.

Key Insights

In drawing together all the views and intelligence gathered through the series of workshops we heard that there are a number of crucial barriers and challenges that reflect the experience of local authorities and their stakeholders face in the current policy regime. These insights are used as a structure for the recommendations for the emerging EOR regime.

As part of the feedback on the draft report, participants of the workshop series and the Environmental Officer Group were asked to rank these barriers in order of importance.

The table below is set out in order of importance as a result of that feedback process.

| Insight | Commentary |

|---|---|

| There is an acknowledged lack of inhouse expertise on environmental assessment. |

The most significant barrier within the current policy regime is lack of confidence in dealing with environmental assessment issues. The workshop series highlighted the shortage of capacity and competence within LPAs, which led to an inability to feel confident assessing reports and environmental impacts effectively. Environmental assessment should be, and in many regards is, very much bread and butter work for most planners on planning applications that fall below the EIA thresholds and policy development of environment policies of a plan. Whilst the lack of environmental assessment expertise within the public sector is a primary barrier more widespread is a lack of confidence for planners to have autonomy on decision making. |

| The current environmental assessment regime contains an inherent element of uncertainty, and this sits at odds with other elements of the planning system. |

There is an inherent element of uncertainty and predicting the ‘might happens’ and uncertain effects in the current environmental assessment regime contains. Plans and development proposals have a desired outcome, so the uncertainty of effects is turned from ‘cloudy’ to ‘crystal clear’ to fit with certainty needed for plans and examinations. There is evidence that developers retrofit EIA to make their proposal acceptable, whereas the original vision for EIA was that it should inform what the proposal is. This does not work in practice. Any EOR regime would need to be an iterative process rather than a single reporting stage and require proportionate evidence at stages of project/scheme development to mitigate this current challenge |

|

There is a fundamental knowledge gap between what environmental assessment does and is and what policy is and does. |

A failure to understand the basic differential between whether a plan or project does/doesn’t have ‘Likely Significant Effects’ alongside some confusion about the difference between the assessment of significance and mitigation of an effect, and how that related to compliance with planning policy is found in both nonprofessional and professionals in the planning sector. |

| The current policy regime generates significant amounts of paperwork and documentation. | This makes interrogation of the data difficult to establish the important points and environmental effects identified. The result is that analysis of the documentation by councils is fraught with an overly cautious approach to screening, scoping and assessing impacts. |

| The lack of guidance from Government is the key issue. | Practitioners have to rely on guidance produced by professional bodies but that guidance is not typically specific to EIA/SEA and can be applied equally to non-EIA development. This adds to the cautionary approach, fear of legal challenge and overall lower confidence in undertaking environmental assessment. |

| There is a lack of monitoring of the forecast impacts or mitigation. | The workshops provided confirmation that there is a lack of monitoring, with many proposed mitigation measures either not implemented as proposed or ineffective. Councils are resorting to an aspirational approach to the setting of indicators and monitoring in SA/SEA, when actually these cannot in practice be monitored. |

| Inconsistency of approach in environmental assessment (both EIA assessment and SA/SEA) is a significant barrier in the current environmental assessment regime. |

Whilst assessments use common themes as headings (e.g. air, water) there is significant variance in the indicators and datasets used within assessments. The current policy regime has resulted in assessment authors ‘doing their own thing’ and setting the assessment frameworks in a multitude of formats. This is coupled by an increasing tendency to include locally distinct indicators due to the risk of legal challenges that something may be missed from the assessments. Participants told us this is true for all assessment types e.g. those prepared by developers as EIA, SA prepared by consultants and in-house EIA or SA/SEA. |

| The scope of environmental assessment has become too broad and there is a need to refocus on the implications of the land use. | Other elements of environmental impacts should be captured by permitting, licencing, operational controls and other regulatory regimes. |

| Subjectivity clouds the overall ethos of what environmental assessment is trying to achieve. | Guidance and support to build confidence is needed, the example of landscape & visual impact assessments was cited as a policy where subjectivity has been made transparent using guidance and standardisation of approach. |

| There is a significant lack of access to robust and consistent data. | Participants generally agreed that using nationally set objectives and indicators linked to long-term trusted data which was centrally managed would be a most welcome change in the system. |

| Councils aren’t ready for digital assessments. | Participants expressed frustration at how archaic councils are in their reluctance to accept a non-PDF format from a corporate stance and that planning departments and officers were frustrated by this. The objection to accepting new digital based formats was that are not ‘uploadable’ or ‘submittable’ in the same way a PDF is and therefore limited how the council could make the document available to the public and meet accessibility requirements. The issues of councils not wishing to accept a format that was externally hosted was also raised |

Accessibility

Overall

In a nutshell the complexity of process and documentation inhibits engagement. Accessibility is the biggest issue, and the current system is far too difficult and complex for elected members and the public to access and utilise SEA, SA, EIA in any meaningful way.

The current policy regime generates significant amounts of paperwork and documentation which makes interrogation of the data to establish the important points and environmental effects identified difficult. The result is that analysis of the documentation by councils is fraught with an overly cautious approach to assessing impacts. Participants stated this is largely a consequence of poor scoping. Environmental assessment should be focussed on the likely significant environmental effects of the proposed development. The scope of EIA has been progressively expanded to cover every conceivable impact pathway, which leads to expansive documentation. We heard criticism that the law is not sufficiently clearly defined and therefore LPAs and consultants adopt a precautionary approach to the scoping of EIAs.

We heard in all of the workshops that the prevalence of cut and paste is the biggest issue for environmental assessment produced by external consultants. It’s a case of ‘spot the other authority’s name’ and this leads to a lack of confidence in the report's findings. Participants were nervous about providing specific examples where they as the local authority had been caught out with another councils name in the documentation or draft reports; however the issues was raised so frequently that it is a fair assumption to say it happens to a substantial degree.

Evidence provided by participants supports the knowledge that engagement levels in environmental assessment are generally low by the public and members as the process is too difficult and complex. This results in EIA and SA being seen as a technical exercise and so given little weight in local decisions.

The exception to this is resident, community and charity/activist groups using EIA/SEA as a means of challenging proposals or plans to which they object. EIA and to a lesser extent SEA/SA have provided fertile ground for legal challenges to planning permissions and plans, which suggests that engagement with the reports is not such an issue for these groups. It is important to remember that EIA/SEA are there to facilitate public engagement in environmental decision making, and legal challenges are tangible examples of active public engagement. However, the actual level of legal challenges and public interaction with EIA/SA/SEA when compared to the wider public engagement with planning is small and limited.

The current environmental assessment policy regime mean that social and economic factors end up being trading off against environmental impacts. Trade-offs are not always transparent, and the weight of the benefit give to the creation of jobs and houses is seen as overriding environmental effects. This trade-off happens within the assessment and is done a cursory high level on the actual benefits new jobs/homes provides. This is seen by the participants as trying to force planning judgement and the wider planning balance into a rigid matrices format. Participants said they find this unhelpful for communicating the purpose of environmental assessment.

Local members do not engage with the scoring and pages of plus/minus type analysis. This is seen as trying to hide how the site assessments have been made. We heard examples of where SA had taken a more narrative site commentary approach which members might engage with more meaningfully.

The scope of environmental assessment has become too broad and there is a need to refocus on the implications of the land use. This is an important point - about the geographical and temporal scope of assessment. Participants, particularly environmental specialists, felt at present the law is ambiguous through the inclusion of catch-all lists for the types of impacts (direct, indirect, secondary, synergistic, cumulative, etc.) that might need to be covered in EIA/SEA. We heard this leads to a precautionary approach by LPAs in particular due to the risk of legal challenge. For example, in a climate change context there is a lack of guidance in relation to the scoping in or out of GHG emissions and how far up or down the value chain an assessment should go - for example – for upstream emissions - should you consider the GHG impacts of mining and smelting the iron that creates the iron components of an aircraft? for downstream emissions should the GHG assessment for an aircraft manufacturing facility include the likely lifetime emissions of each aircraft produced?

Inconsistency of approach in environmental assessment (both EIA assessment and SA/SEA) is a significant barrier in the current environmental assessment regime. Whilst assessments use common themes as headings (e.g. air, water) there is significant variance in the indicators and datasets used within assessments. We heard from participants who were predominately planners that the current policy regime has resulted in assessment authors ‘doing their own thing’ and setting the assessment frameworks in a multitude of formats. This is coupled by an increasing tendency to include a multitude of locally distinct indicators in addition to the common themes due to the risk of legal challenges that something may be missed from the assessments.

Participants who were environmental specialist had a different angle to why environmental assessment is seen as inconsistent and inaccessible. We heard that topics such as ecology and landscape have defined approaches to impact assessment that are typically applied in EIA - the Chartered Institute of Ecology and Environmental Management (CIEEM) guidance on Ecological Impact Assessment (EcIA) and the Landscape Institute/IEMA Guidelines for Landscape and Visual Impact Assessment (GLVIA). The same applies to other established and science-based disciplines including air quality, water environment, noise, with guidance from other bodies (e.g. CIEEM, LI, IAQM, etc.)

Direct quote from Participant - The lack of guidance from Government is the key issue, as practitioners have to rely on guidance produced by professional bodies but that guidance is not typically specific to EIA/SEA and can be applied equally to non-EIA development.

To make EOR accessible and engaging for all requires a renewed focus on better scoping and the production of more accessible non-technical summaries with increased use of digital platforms. What's needed is a rebranding of the nontechnical summary – this is what communities and politicians can engage with. It is acknowledged that currently non-technical summaries are not without problem and can be used a public relations promotional exercise. Nevertheless, the group found that they present a level of information that is accessible to non-industry stakeholders. Recommendations are that EOR will need to simplify and regularise the process, without losing some scope for local flexibility to make sure EORs are relevant to members and the public. EOR will need to be structured in a way that prevents subjective or biased promotion and instead provides unbiased assessment in a plain English and easy to access format.

Whilst there was widespread support over the workshop series for a streamlined and simplified environmental assessment process; there was a feeling of caution around the tendency for ideas to start simple then progressively get more complex as they get challenged and the ‘what ifs’ come into play. This has certainly been the pattern for the current EIA/SA/SEA policy regime with legal caselaw and more layers of policy or guidance being added over the years.

Participant's felt it is important to understand what a community wants and why; accompanied with a clear understanding of what they are and are not getting through the environmental assessment process.

Issues particular to EIA

The way in which EIA has been embedded into the land-use planning regime in particular has provided a fertile ground for legal challenge. Some participants stated their view was it could be argued that from the perspective of improving environmental decision making and public engagement that case law has demonstrated that EIA is fulfilling its function in providing a high level of protection of the environment.

The voluminous nature of technical evidence submitted alongside screening & scoping applications and Environmental Statements (ESs) means that officers have difficulty accessing the pertinent information on predicted environmental effects. We heard that applications can be accompanied by huge boxes of ecology and specialist surveys, with officers regularly comparing it to ‘finding a needle in a haystack’ for the nugget of information on what the actual “main” or “significant” environmental effects are.

A failure to scope matters out of the ES also leads to extensive documents that are then challenging to interrogate. The ES should focus only on those aspects of the environment that would experience 'significant' effects, but there is a tendency for EIA to cover all conceivable impacts even where those effects would not be of a scale or type that would warrant inclusion in the EIA. Whilst the ESs prepared by large consultancies will typically have some elements of standardised format and approach, there is an inconsistency in format and coverage across ESs. There is a need to standardise in terms of the content and structure.

Participants, especially environmental specialists, expressed some frustration with EIA, and to a lesser extent SEA, in that the UK has transposed EU regulations that are very process heavy, setting out complex procedures that LPAs have to follow in receiving, publicising and utilising ESs. The use of secondary legislation to introduce EIA and different approaches for different consenting regimes, was a view raised by participants who felt this means there has been inconsistency in the application of the requirements of the EIA Directive.

The current EIA regulations require officers to check additional matters and thresholds that sit outside DM regime, and this is seen as an additional burden to processing applications.

We heard in multiple instances criticisms of the quality and content of submitted ES’s, the most common critique was ‘spot the other authority's name’ with cut and paste is seen as biggest issue.

Issues particular to SA/SEA

The prevalence of cut and paste is a big issue for SA/SEA produced by external consultants, it’s a case of ‘spot the other authority’s name’ and this leads to a lack of confidence in the report's findings.

The reports are so long as to be inaccessible. The high volume of information in SA/SEA reports mean officers regularly compared it to ‘finding a needle in a haystack’ for the nugget of information on what the actual “main” or “significant” environmental effects are.

Direct quote from participant – ‘Reports are generic – so where is the value?’

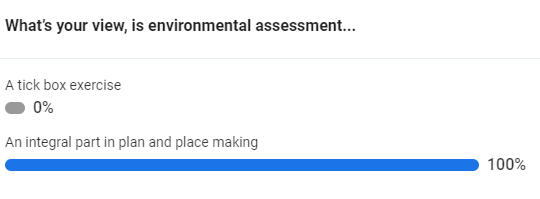

That being said, we heard overwhelming support for the current system of environmental assessment as an integral part of the plan making process. This support can be seen in 100% response rate from the report feedback gathering.

Some thought that Sustainability Appraisals/SEA are actually useful pieces of evidence in plan making, but it is difficult to get key info out and recognise what it is; primarily due to the volumes of documentation and complexity. SAs are valued as they bring evidence to the plan process that can underpin DM policies and judgements on the development strategy. Others thought it was just a tick box exercise. The value in SA and SEA are that they ensure environmental issues are pushed up the agenda, highlighting choices and judgements at plan making stages.

The main barrier is that this crucial and useful role is not understood by communities or other stakeholders within the council such as senior leaders and councillors. In particular, Local Plan consultations are flooded with community responses raising concerns on whether certain environmental, social or economic issues have been fully considered in influencing the plan development. Indicating that people submitting Local Plan responses are unaware of the SA/SEA process in plan making.

Direct quote from participant- ‘Nobody reads it (SA/SEA) so it makes our plan consultations a battleground’

There are a number of challenges to overcoming this barrier, namely that currently reports are long, generic and not presented in easily understood way. Furthermore, beyond the scope of environmental assessment, there is a wider lack of transparency around how councils consider all parts of the local plan evidence base in the round when making choices and decisions over strategy, policy and site selection.

Conflating the purpose of the various elements of environmental assessment

Overview

We heard that consultants, officers, legal professionals, members and the public conflate the environmental assessment with whether a scheme is acceptable in planning policy terms. A key issue is the lack of dedicated environmental professionals in LPAs - this applies to both EIA and SEA. Planners, both development management and policy, may not have sufficient knowledge of environmental systems and processes to be confident in determining what environmental impacts need to be assessed. They also need specialist support to evaluate whether the environment information submitted by developers is sufficiently scientifically robust or how to define whether the policies and sites proposed for inclusion in Local Plans have ‘likely significant effects’.

One notable example heard was where an elected member had challenged their own council officers on their judgement pertaining to an EIA screening opinion and was unable to separate the EIA process from the landscape and other environmental impacts the proposal had in policy terms.

The process of plan making and environmental assessment have become conflated, and even individual parts of environmental assessment have become conflated. There is a lack of clarity of purpose between SA and SEA as well as the confusion between SA and plan making.

SEA, as conceived in the EU Directive, is essentially EIA for Plans and is focused on understanding the likely impact of the Plan on environmental systems and processes.

We heard there is confusion as to the purpose of SEA within plan making, which has largely arisen as a consequence of the conflation of SEA into SA.

The role of SEA is to identify potential environmental harm that could arise from the implementation of the plan, with a particular focus on the area of land covered by the Plan. The SEA, like EIA, should also identify measures that could be deployed to address the risks of environmental harm associated with the Plan. SEA also requires that a comparative assessment be made of the environmental harm likely to arise from the implementation of reasonable alternatives to the proposed Plan. The purpose of this requirement is to place such environmental information in front of those making the decisions namely policy planners and elected members so that they might make informed decisions.

Unlike the Habitats Regulations the SEA Regulations do not have the power to prohibit the inclusion within a Plan of a policy or site that was found to be environmentally harmful by the SEA process. The SEA does however render explicit the environmental information that has informed decisions and gives communities and other parties the opportunity to participate in the decision-making process and give their own views on the likely environmental implications of the Plan

The role of SA is to challenge the ability of the proposed plan to contribute to wider sustainability objectives and therefore has a broad focus but is more about direction of travel than any form of quantitative assessment. Much of this confusion has arisen as a consequence of little or out-of-date guidance. Reference was made to the 2005 guidance and speculation that it has never been updated in light of recent practice.

The role of SEA is to provide a clear account of the likely significant environmental impacts of the proposed alternatives to help inform the subsequent decision making process. It is not universally understood that is not the job of SEA or SA to generate options for the Plan, instead its role is to act as a challenge function or test for the options previously generated against the identified environmental constraints The role of SEA is simply to ensure that the implications for the environment are set out clearly and are placed before those making the decisions. This is where the conflation of SEA and SA has not helped - as the inclusion of social and economic considerations dilutes the focus of the assessment and increases the scale of the associated reports.

The SEA process is about information provision - it is for the plan makers to then explain how they have taken that information into account and how it has helped to inform their decisions. The SEA Regulations do not require that an explanation be provided in the environmental report of the way in which plan makers have used the environmental information to inform their decisions, that explanation is required in the post-adoption statement (Reg 16). However, through SA as well as for SEA and EIA the story of how the plan or project was formulated should be a key part of the assessment report.

We heard there is a lack of clarity in practice with the difference between plan making and having a narrative of how the strategy developed and the SA/SEA. There is confusion over what is plan making and what is sustainability appraisal, which used to be clearer but has recently become lost. The explanation of alternatives for the plan strategy and sites is part of the plan making process and it should be accompanied by a visible narrative to communities but it’s not. When asked why this might be, participants concluded that a mixture of less experienced officers, staff churn, a reliance on outsourcing and a lack of clear guidance from government on the ‘how’ to undertake SA/SEA have all created a perfect storm.

The workshop series highlighted opposing views on the effectiveness of environmental assessment. Most participants in the workshops expressed the view that environmental assessment as an integral part of the plan making process. A smaller proportion of participants expressed the view that environmental assessment (SA/SEA/EIA/ES) is a tick-box exercise that doesn’t form a part of place or plan making. It is worth acknowledging that many of those views were in relation to EIA Screening and Scoping as a tick-box exercise. These opposing views and the fact that more people said they saw the benefit of environmental assessment in plan and place making sits at odds with other stakeholder engagement undertaken by DLUHC and others.

When probed about their views supporting SA/SEA, participants responded with why they supported SA/SEA so strongly. We heard that the SEA/SA process can help with key pieces of work such as site selection, as it’s a useful means of identifying the matters that will need to be flagged up as key development criteria for allocated sites (e.g. the site adjoins an area of Ancient Woodland, or is prone to surface water flooding, etc.).

During the feedback process this split between views was tested with the officer group established and the background of the participants in that smaller group was gathered. This corroborated what the wider workshop series found e.g. that planners recognised the important role environmental assessment plays in plan and place making.

Participants reflected that the SEA/SA can be a useful hub to pull together the findings of other supporting technical assessments and studies, such as transport assessments, SFRAs, HRAs, landscape character work, etc. In order to do this well the policy planners and environmental specialists need to work closely, to ensure that topic specific assessments are undertaken early enough to allow sufficient time for their findings to be incorporated into the SEA/SA. This also improves the robustness of the data on which the SEA/SA relies and provides a sound evidence base from which recommendations can be made to address any harmful impacts that the plan is expected to give rise to.

Participants felt this split in views was due to a key issue, namely that there is the lack of environmental specialists in LPA. Planners may not have the necessary knowledge of environmental systems and processes that environmental specialist have to be able to apply the requirements of current UK law in this area confidently. Planning training in the UK does not typically include the level of study of the environmental sciences and environmental law that is necessary to be confident in the use of EIA or SEA in decision making. Environmental assessment should be, and in many regards is, very much bread and butter work for most planners on planning applications that fall below the EIA thresholds and policy development of environment policies of a plan. Whilst the lack of environmental assessment expertise within the public sector is a primary barrier more widespread is a lack of confidence for planners to have autonomy on decision making.

In relation to the view that environmental assessment is a tick-box exercise participants were keen to clarify three things.

Firstly, that the procedures are almost checklist like in nature of aspects of environmental assessment this naturally steers the process towards being a tick-box exercise.

Direct quote from a Participant - SA often feels like a tick box exercise, as much as you try and make it not that way, it does feel like sometimes there are very few, if any, real alternative, mutually exclusive options to assess and therefore the assessment doesn’t help.

Secondly that ALL environmental assessment CAN be a tick box exercise if not undertaken correctly and meaningfully. Experience suggests that when external consultants prepare the assessment it is a tick-box exercise. However, that’s not to say that there isn’t a great deal of value in EIA/SEA/SA when undertaken correctly and with an open mind. Thirdly that all too often SEA/SA end up being done retrospectively whereas the process of plan/policy development and SEA/SA should be iterative. Retrospective SEA/SA is just box ticking. If it is done properly and timely, it is not.

Participants want to get back to consistently using the SA to inform judgements – at the moment there is a feeling that the SA must point to the “right answers” and so the only people engaging with the SA are those that want to object to a site and are looking for evidence of environmental harm or identify the steps that could be taken to address that harm. This creates a vicious cycle of increasing cynicism surrounding the SA/SEA.

Sometimes all the development options/alternatives set out in an SA can be resisted or supported; there is a perception from outside the process that SA rarely presents a viable alternative for development strategies e.g., Green Belt release versus increasing density (high buildings) in towns is not seen as a real choice by members.

Participants all expressed a desire for the emerging EOR policy regime to make any new reporting format shorter, more succinct and that it is really important that information is presented in an easily understood way.

We heard that SA needs to be better integrated into the plan-making process to properly inform judgements. One LPA has had useful sessions with elected members when the SA was used to judge the pros and cons of different sites. This was at an early stage in the plan process.

Cautionary approaches and the need to de-risk the regime

Overall

We heard of widespread concern over the litigious minefield that environmental assessment brings, resulting in a hyper-cautious approach being taken by councils in all aspects of the current policy regime.

Direct quote from participant – ‘It’s a lawyers dream’

There is an acknowledged lack of in-house expertise on environmental assessment, which is leading to precautionary behaviours. Alongside the legal risk councils face the reputational risk inherent in the current system; councils want to deliver robust decisions as part of their planning function. The last 5yrs have seen an escalation in challenge coming from local resident or opposition groups with the current environmental assessment regime seen by many as the preferred vehicle for opposing, stalling or stopping an unwanted local development.

Direct quote from participant – ‘It’s difficult as a planner to feel confident with making the decision on it’. (This was relation to EIA Screening and Scoping Opinions)

The predominate precautionary behaviour seen is a lack of challenge to submitted documentation and technical evidence. Officers find it difficult to challenge without having the supporting environmental expertise. Low levels of confidence within LPAs or lack of expertise in this field often means external resource has to be bought in. The low levels and sporadic in-house expertise in many councils cause them to be risk averse because of the likely threat of a legal challenge if they push back against developers on EIA or SA grounds. We heard from four local authorities during the report feedback gathering that expertise had once been present in their councils but that this resource had been lost either due to budget cuts or an individual officer with a particular interest and skills in environmental assessment had left the authority.

When legal advice is sought often the advice is ‘this needs expertise to come to a view’. This then triggers external support being procured, causing more work and financial impacts to do this. We heard from councils where this extra finance and resource cannot be accommodated so the officers end up just having to accept what’s said by the ‘developers' expert’ without any recourse to challenge.

Issues particular to EIA

The scrutiny level of EIA Scoping & Screening stages by developers, national environmental organisations/charities and public/resident groups is high, so this leads to EIA not being focussed enough. The regulations are also so inclusive as to exclude nothing. A common viewpoint was that parts of the regulations are pointless, rigid and include unnecessary elements which has contributed to the caution councils take.

Direct quote from participant - ‘An absolute nightmare! Developers and us don’t want to scope anything out’

We heard of numerous pre-screening activities to determine whether an EIA was needed being undertaken by councils as a by-product of the cautious nature and lack of confidence in officer ability in formal EIA Scoping & Screening opinion processes. Examples of internal pre-screening processes using checklists, tick-box lists and proformas asking key questions were all cited during the workshop series. Participants when discussing ‘pre-screening’ referred to both action taken before an EIA screening request comes in and as a pre-acceptance activity at the time of validation. Participants stated this pre-screening process can add time and resources to undertake, adding to the department burdens. The principal reason given for why councils felt it necessary to run a pre-screening activity was to provide the council with legal cover and an embedded nervousness that something would be missed.

Likewise, the use of the Environmental impact assessment screening checklist is widespread and is considered to be a useful tool for officers, however councils are reluctant to make the completed checklist publicly available alongside the application documentation for fear of legal challenge or scrutiny by local opposition groups.

Reference was made through the workshop series about the thresholds for development needing EIA, explicitly Schedule 2 10B. Many felt the current planning regime means that development of a smaller scale is submitted to councils but without the technical evidence. This triggers officers into having to make decisions on opinions which are challengeable. We heard suggestions that screening is one of those areas where clearer guidance from UK government as to the types and scales of development that warrant EIA so the large amount of precautionary screening of projects that LPAs have to engage in could be addressed relatively easily through a review of the thresholds and criteria set out in the TCPA (EIA) Regs 2017 . This could be particularly applied to those broad categories in Schedule 2 (i.e. paragraph 10(b) – urban development projects) that are used to mop-up developments that don’t fall readily into the more tightly defined categories.

Participants felt that schemes of 150 dwellings would be best addressed by having their environmental impacts assessed as part of the ‘normal’ planning balance rather than through EIA to reduce the litigation risk.

Issues particular to SA/SEA

Producing SA/SEA in-house is an option for local plans teams, but participants said that a council will often seek to reduce risks of a legal challenge by commissioning an external consultancy as this is seen as a safer option.

The current system is not trusted by the public and there are frequent sceptical perceptions around vested interests of the council being the author of SA/SEA reports when it is the same council which wants its local plan to get through.

The consensus view is that SA/SEA has morphed into an overly technical process and SA/SEAs have become too formulaic and technical. We heard that LPAs have lost sight of the fact that judgements are needed and SA/SEA should help inform choices rather than lead to a single right answer. Under-pinning this is the risk of legal challenge, many officers have had long sessions at an examination defending their judgement for making a tick or cross in an SA/SEA.

People used the term “legal hunting ground” to describe SA/SEAs at examinations, with expensive barristers using an SA/SEA to unpick the strategy for individual site allocations on behalf of their developers. The arguments over the soundness of the SA/SEA can become very site specific and lose sight of the strategic role of an SA/SEA.

The majority of participants in the workshop series were concerned that the value of the SA/SEA process in informing judgements and choices during the plan making process was being lost as the technicalities were legally challenged by objectors to trying to unpick the plan. This is explored in more detail at Future EOR recommendations in this report.

Monitoring

Overall

At the start of the workshop series, we posed the theory that in the current policy regime there is a lack of monitoring of the forecasted impacts or proposed mitigation, and that many proposed mitigation measures are either not implemented as proposed or ineffective. The views and opinions we heard confirmed that hypothesis and we heard first-hand accounts of where monitoring is not resourced and therefore

- At the project level - limited to reactionary monitoring when complaints are received.

- At the strategic level – limited to wider monitoring of the plan with aspirational indicators or the monitoring effects at a very high level with no tangible link to the SA/SEA predictions

The consensus view across the workshop series was that monitoring is lacking and when it does occur it bears no positive link to what is happening with actual environmental impacts. It was agreed that long-term land management and stewardship are a key missing element of environmental monitoring.

Environmental assessment is seen by the participants as a linear exercise where monitoring is the end, which predominately trails off. There was optimism and a keen interest by all at the suggestion that EOR will be a circular process, effectively closing the feedback loop; however, there are very few details on how EOR would work at this stage. A reporting requirement could help to drive better monitoring but it would need to have a clear purpose and be supported by public engagement to ensure political buy-in. Systems thinking should be applied to the development of EOR to ensure a circular, iterative approach whereby mitigation is adaptive.

We heard that the primary barrier to monitoring was a lack of resources, officer time and expertise. Participants expressed the understanding that there needs to be checks and balances in the system; however proper monitoring requires significant LPA involvement, but this desperately needs a cost recovery mechanism. Cost recovery has the potential to provide resources for local planning authorities to carry out monitoring but there is a lack of understanding about how this might work in practice.

Most participants had the view that monitoring cannot rely on developers self reporting and that LPAs have an aspiration to robustly monitor environmental effects but are currently unable to financially or time resource it.

This theme highlighted the disparity between the approach to monitoring taken by county councils and districts. This is primarily down to the application types. For example, county councils dealing with county matters, minerals and waste which almost always require an EIA/SEA or SA. Local planning authorities are currently able to recoup fees for minerals development and landfills and this tends to be within county councils. Participants speculated whether this recouping of monitoring costs can this be extended to district typologies of application such as residential and mixed-use schemes.

Officers from county councils provided examples of monitoring practices involving frequent site inspections & specialists such as ecologists undertaking receptor site analysis. These are clearly resource intensive and it would be challenging to translate this level of resourcing into district planning departments on residential and mixed-use development. It was acknowledged that minerals and waste developments are unique in that they have a finite lifespan e.g., a mineral extraction development will cease once the mineral is extracted. This makes monitoring of the development easier and that site restoration and remediation form part of that monitoring feedback loop. Districts deal with development types that are harder to monitor longer-term e.g., a site is developed, the house purchased, and the end user is a householder who may undertake home improvements detrimental to improving environmental outcomes. This lack of a single end user and finite end use makes monitoring of predicted environmental outcomes extremely difficult, especially when individual EIA and ES’s have used datasets and indicators set by the authors rather than a nationally set approach.

We only heard instances of remediation and its monitoring from county matter developments and a very few instances of district-level development. The latter was as a result of enforcement complaints, usually where contaminated land was known to be present.

Issues particular to EIA

An issue related solely to EIA monitoring was the changing of the level of information presented at screening and scoping stages to the eventual ES submitted with the planning application. This process of dilution of data by developers/applicants is often when the ES is watered down from the thresholds and promised level of surveys in the scoping opinion submission. This means that what was needing to be monitored in terms of impacts, effects and mitigation is different or less clear than what the LPA agreed at screening and scoping stages.

Issues particular to SA/SEA

A range of participants expressed the view that creating indicators, KPIs and other monitoring matrices for either monitoring the predicted effects within Sustainability Appraisals or for wider monitoring of the Local Plan can be problematic. Namely that monitoring indicators are being drafted without the ability to collect or have access to the data needed to measure performance against that indicator accurately. Councils are tending to monitor what is convenient and available rather than what is the right indicator for measuring policy outcomes. This is leading to an aspirational approach to monitoring frameworks. A frequent mantra was ‘we know what we need to monitor for this impact/effect, but we simply don’t have the data to do so’. Participants were clear to state that officers can determine what should be monitored and have the aspiration to monitor the right indicators for their sustainability appraisals and plans however the lack of available and consistent data means that frequently aspirational indicators are included within monitoring frameworks that cannot be reported on.

Consistency of assessment approach, Data and Digital

Overall

Participants confirmed that there is a significant lack of access to robust and consistent data.

There is a need for data to be trustworthy and transparent over who owns and manages it. There are rich data sources held by external groups and bodies which are useful to officers presently, but these are frequently challenged by stakeholders as to their appropriateness. We heard how the Natural England Magic Map geospatial tool was widely used by council officers until there was a loss of trust in the quality and up-to-dateness of the data at which point councils stopped using it as often. A set of national indicators would help to drive more consistent data requirements and improve data availability. This will need some careful thinking e.g., a menu of national indicators would never be big enough to cover all eventualities, and some local indicators would always be needed as well. Some thought should be given to what data national agencies could and should be required to publish to support indicators.

Subjectivity in the assessment of environmental effects is seen by many as a fundamental flaw of the current policy regime.

As stated previously there is a lack of consistency of format with assessments, both EIA and SA/SEA, and this compounds inconsistency in assessing the level of various effects and impacts.

Direct quote from a participant – ‘It feels like you would get ten different answers from ten different people.’

Whilst it was acknowledged by the participants that subjectivity is inherent in environmental sciences, the quote above demonstrates how subjective using a simple matrix can get. We heard multiple times about disagreements between officers on whether an effect was a double minus or single minus or even neutral depending on the view taken by an individual. The assessment matrices created in Sustainability Appraisals are considered to be far too subjective to be meaningful. With the use of vague and subjective symbols representing the assessed level of effect such as ++ and - - , these can be read a hundred different ways and lack the nuanced narrative needed to articulate the level of assessed effects. Even assessments which use a narrative approach could be improved if the data was standardised and clear on what the baseline and desired quantum of positive or negative effects are. There was a sense of widespread support that any EOR policy should start with the same/standardised datasets to enable a standardised approach to reporting so that what is produced are similar assessments regardless of geographical location.

However, this view was caveated with some concerns about the use of nationally set objectives and indicators, as these may miss impacts that are significant in a local context and may not be appropriate to the full range of development covered by the TCPA and NSIP regimes.

Data coverage and accessibility are issues, but there appear to be some optimistic assumptions being made about the existence of data that may not be there or be there with sufficiently wide coverage for it to be useful in plan making or site-specific assessments.

For example, when discussing statutory consultees, we heard from participants that whilst SSSIs are subject to requirements for condition monitoring and reporting it is known that because of Natural England's lack of resources not all SSSIs are being monitored as frequently as would be appropriate. The same can be said for water quality monitoring for surface and ground waters, for which the Environment Agency is responsible.

If LPAs are supposed to evaluate development proposals against national environmental indictors using data that is consistent across the whole of England then the bodies responsible for collecting that data will need to be properly resourced. That data will also need to be readily available to LPAs, who themselves will have to be resourced appropriately to ensure that they have access to appropriate technical experts in both data handling and interpretation as well as sufficiently resourced GIS support.

The Environment Act and emerging environmental assessment proposals will introduce a renewed focus on how we will plan for the environment. There is a shift towards a need for ‘big picture’ thinking and introducing a mechanism for long term monitoring. For EOR shifting towards an outcome-based approach means there is a need for new guidance and legislation on how EOR, Biodiversity Net gain (BNG), Local Nature Recovery Strategies (LNRS) will all fit together and how the long-term condition and improvement of the environment will be monitored. The increasing importance of the interaction between environmental effects and climate change was a strong theme within the workshop series. Long-term monitoring is going to be key to implementing BNG and with BNG becoming mandatory in November 2023, will be an area that LPAs are grappling with alongside EOR. Many of the messages we’ve heard through this workshop around the challenges of monitoring have been the same as those raised at workshops PAS has run on BNG. The same can be said for environmental expertise, i.e. that lack of capacity and expertise is the issue most frequently raised at workshops PAS has run on BNG and wider environmental planning, as well as an issue for councils dealing with nutrient neutrality matters. The issue of assurance for BNG assessment and delivery is one that is being explored by Natural England for BNG.

Significant lack of data read across between strategy and project level. We heard how allocated sites when they come forward for consenting tend not to refer to or use the data sources in the SA/SEA for the Local Plan. Furthermore, we heard that DM officers, due to a lack of understanding of SA/SEA at plan making stage, do not realise this is a source of data to be used in the planning balance or that they should require the applicant to demonstrate read across from strategic to project level assessment.

Data presentation and the readiness of councils for the digital agenda was a theme of the workshop series. We heard that councils had been prevented from accepting digitally based, non-PDF, environmental assessment (EIA/ES/SEA/SA) due to corporate IT departments. This included things such as interactive 360 view site surveys and hydrology simulations for flooding extents. Upon further discussion, the principal barrier appeared to be a reluctance to accept a non-PDF format from a corporate stance and that planning departments and officers were frustrated by this. The objection to accepting new digital based formats was that are not ‘uploadable’ or ‘submittable’ in the same way a PDF is and therefore limited how the council could make the document available to the public and meet accessibility requirements. The issues of councils not wishing to accept a format that was externally hosted was also raised.

Participants expressed frustration at how archaic councils are in this regard and the Institute of Environmental Management & Assessment (IEMA)web resource on emerging digital innovations was cited by many. IEMA is one of the professional bodies for those working in environment and sustainability. They have complied a webpage to host examples of digital innovation in EIA, the website provides best practice guidance, case studies and webinars on Digital Impact Assessments. There are other examples of these types of resources produced by Chartered Institute of Ecology and Environmental Management (CIEEM), Chartered Institution of Water and Environmental Management (CIWEM) and the Royal Town Planning Institute (RTPI).

Everybody wants standardised data. All workshops concluded that a consistent approach to datasets would be a way to standardise the approach to environmental assessment, both EIA and SA/SEA, to streamline the system. Participants all expressed support for a data-driven approach to EOR and the possibility of a nationally set range of indicators and datasets.

Issues particular to EIA

We heard from participants that frequently developers of multi-phase developments or multi developer/ownership sites where more than one developer is involved don’t share data and tend to assess impacts differently. This really confuses the public. We were unable to get specific developers or sites to be named by participants.

There is an acknowledgement that this leads to ‘lost learning’ and that the private sector seems unwilling to learn either from best practice approaches to compiling EIA or assessing impacts accurately from previous sites or phases.

The pre-submission decisions taken by developers cause challenges for LPAs. Project/scheme design work and PR from the developer occur before the technical work is undertaken. This is a particular issue for residential or mixed development schemes. Glossy concept diagrams and slick CGI are frequent features of outline consents needing an EIA. Many decisions on development quantum's, based on financial returns, are made before any technical analysis of significant or likely effects work is done, thereby retrofitting the EIA to the scheme with no input into this from LPAs. Developers use EIA as a one hit process rather than a cyclical process which avoids full consideration of the mitigation hierarchy throughout the timeline of consenting e.g., outline to delivery. Any EOR regime would need to be an iterative process rather than a single reporting stage and require proportionate evidence at stages of project/scheme development to mitigate this current challenge.

Direct quote from participant - ‘developers have a plan then they are told they need to do an EIA and they make the EIA fit the proposal. Whereas the original vision for EIA was that it should inform what the proposal is. This does not work in practice because this is the commercial reality we are in’

Developers commit (via screening and scoping opinions) that an ES will follow guidelines, standards of surveys and parameters that are frequently not followed through and many participants experience a ‘watering down’ of quality when it comes to planning application stage or conditions discharge.

There is crossover with what we heard around data quality and resourcing. Officers expressed frustration where multiple developers assessing the same thing but with no learning from what’s already been done. An example given was where four consecutive projects from the same developer, but they didn’t build on experience of what’s worked/not worked and build this into a programme of monitoring. This type of practice is really challenging and frustrating for officers and adds to the resources taken for the EIA process.

Issues particular to SA/SEA

Everybody saw a lack of standardised data as a barrier to a more efficient process. All workshops' events concluded that a consistent approach to datasets would be a way to standardise the approach to environmental assessment, both EIA and SA/SEA, to streamline the system. Participants all expressed support for a data driven approach to EOR and the possibility of a nationally set range of indicators and datasets.

The current environmental assessment regime contains an inherent element of uncertainty and predicting the ‘might happens’ and uncertain effects. This sits at odds with the elements of the planning system. Plans and development proposals have a desired outcome, so the uncertainty of effects is turned from ‘cloudy’ to ‘crystal clear’ to fit with certainty needed for plans and examinations.

We heard evidence that the initial scoping of SA and setting of sustainability objectives is time consuming and that the practice of ‘seeing what others had done’ was common. Several participants confirmed that in setting sustainability objectives for their SA they viewed other councils’ SAs and ‘took the bits they liked’. There is lots of cross learning and informal standardisation happening and this is an area which would benefit from having a national source of standardised sustainability objectives and standardised datasets to measure those objectives, perhaps with the ability to include locally specific datasets as additional elements for measuring the objectives. Participants expressed a wish that these should be consulted on widely with the industry and statutory consultees.

Across the workshops focussed on SA/SEA the consensus view was that sustainability objectives can be crude and difficult to measure. Objectives were often accompanied by proxy assessment around broad assumptions on locations and benefits e.g. benefits of housing is linked to the broad quantum rather than location specifics or delivery of tenure types. This means the assessment behind some of the objectives is also very crude and has an over reliance on old unreliable data sources, especially around technical areas such as water quality, flooding and air quality. Participants universally agreed that using national set objectives and indicators linked to long-term trusted data which was centrally managed would be a most welcome change in the system. This would allow an acknowledgement of the data flaws that exist but fundamentally shift the current arguments around appropriate baseline data to a more productive narrative.

Direct quote from a participant - ‘We need to step away from relying on less robust data and accept the data flaws. EOR has the potential to simplify and de-risk the process for us so we can have better conversations’

There were also discussions on how nationally set standards for data submitted by developers would be a significant improvement. We heard examples where officers were trying to link the strategic level assessment and the objectives set in their SA with project level assessment. They commonly found that technical data submitted around the SA objectives was not reliable enough to make any meaningful assessment. One example given was where 30yr old bore hole data was submitted to show the SA objective was met, the officer had difficulty pushing back to say that the data was out-of-date as there wasn’t any set data standards or common datasets. This is felt to be an area where EOR could assist in setting national data standards for technical evidence.

We also heard that setting of national objectives, indicators, data standards and datasets would improve communication and engagement with members and the public.

Management of timescales and of stakeholders

Overall

Capacity and competency within statutory consultees was a reoccurring theme across the workshop series, especially in relation to Natural England and the Environment Agency. The high workloads and staffing resources at statutory consultees was universally acknowledged by participants

Direct quote from a participant – ‘we know they are as overworked as we are but the stuff they send you is rubbish’

Consultee engagement is challenging, and we heard specifically that Natural England struggle to engage as they are so under-resourced. This often leads to delay in LPAs processes as Natural England frequently miss the 30-day deadline for comments. Similar experiences with National Highways and Environment Agency were cited. We heard statutory consultees often ask for an extension to the deadlines (which are legal minimums) and that delays the process as LPAs feel unable to refuse the request.

We heard about the stakeholder consultation merry-go-round experienced by council officers frustrating the development management process. Some participants experience a constant loop of 21 days consultation with all statutory consultees for when a slight change or amendment is made, even if it's for clarification purposes of one stakeholder. This has resulted in statutory consultees changing their position when the amendment was unrelated to this or providing comments which don’t relate to their area of specialism upon which their comments were sought e.g., the Environment Agency providing standard lines on flooding and SUDS when the application details required advice on land contamination matters.

There is a lack of clarity around the necessity, or not, to consult statutory consultees all over again when amendments are made during the application process.

The consensus view is that central Government needs to speak with one voice, so implementation of EOR needs to work for statutory consultees as well.

Issues particular to EIA

Statutory consultees are not providing the independent scrutiny on the quality and content of EIA screening and scoping opinions that they are meant to within the current system. Statutory consultees comments on screening or scoping opinions are often not related to the ‘significant effect’ but to other environmental impacts arising from the application. Participants voiced strong views on the lack of quality responses from stat cons and that this is inhibiting good decision making at councils.

We heard about the stakeholder consultation merry-go-round experienced by council officers in relation to EIA particularly. EIA consultation is considered to be very rigid and onerous e.g., where LPA requires further information, they are required to re-consult, this needs simplifying.

Issues particular to SA/SEA

Significant time and resources are needed going into SA report and overall, the process takes too long. Particularly the case when external consultants are undertaking the work. We heard from a number of participants the lengthy processes involved in tendering, procuring and appointing external consultants is a major barrier to effective and efficient plan-making. Indeed, the process of writing the initial brief is fraught with challenges with frequent occurrences of inarticulate briefs without clearly setting out of the expectations of the council. This is likely to be due to the lack of publicly available clear guidance on how to procure this type of evidence, as well as a lack of knowledge sharing. Due to the long timescales of SA/SEA work often the project lead has moved on from the authority when it is time to begin the next SA or Local Plan, thereby losing that inbuilt knowledge.

We also found that a common theme was the interlinkages between data and timescales. In preparing an SA/SEA significant officer time is spent providing external consultants with data sets including those that are locally specific.

PAS will continue to organise and facilate the Environmental Officer Group to enable continuing discussions with local planning authorities as any new approach to environmental assessment emerges. If you are interested in joining this group then email [email protected]

Future EOR Recommendations

| Issue | Recommendation |

|---|---|

| Improved accessibility |

What's needed is a rebranding of the non-technical summary – this is what communities and politicians can engage with. Recommendations are that EOR will need to simplify and regularise the process, without losing some scope for local flexibility to make sure EORs are relevant to members and the public. It is important for EOR to understand what a community wants and why, accompanied with a clear understanding of what they are and are not getting through the environmental assessment process. EOR policy regime should make any new reporting format to be shorter, more succinct and that it is really important that information is presented in an easily understood way. EOR, in simplifying the process could make it easier to communicate the purpose and role of SA in policy development to stakeholders, the public and those involved in producing Neighbourhood Plans. |

| Clarity of purpose for EOR |

EOR needs to be integrated into the plan process to properly inform judgements. EOR needs to be systems approach to be fully cyclical and iterative. EOR could split out social and economic assessments from the process. The current environmental assessment policy regime mean that social and economic factors end up being trading off against environmental impacts within the assessment itself, instead of as part of a transparent decision-making process on the plan. EOR needs to ensure the delivery of mitigation/effectiveness of mitigation i.e. monitoring and enforcement – a significant resource issue. EOR will need to manage the differing levels of detail between EIA and SEA/SA if switching to a new single report format |

| EOR needs to be better integrated |

EOR will introduce long-term monitoring which is also going to be key to implementing BNG & LNRS and will be an area that LPAs are grappling with alongside EOR. Central Government needs to speak with one voice, so implementation of EOR needs to integrate with other policy regimes; that in combination refocus planning on ‘planning for the environment’ is a wider sense. |

| Upskilling and improving confidence in councils |

EOR needs to be accompanied by clear guidance on implementation and practical process, including templates, checklists and tools. Improving confidence in assessment can be achieved if EOR is aligned to an environment form of accreditation - A brownie badge in EOR. There is a need for a comprehensive (and ongoing) programme of peer-to-peer support, sharing of approaches and best practice and guidance to sit alongside the development of EOR policy. |