Introduction

The Annual Statement of Accounts (also known as the Annual Financial Statements, or sometimes the Annual Financial Report) is an important statutory document produced and published by the council every year. The preparation, and the subsequent external audit, of the document is a significant undertaking for the finance function and the oversight of these tasks is one of the key undertakings for the council’s Responsible Finance Officer (the “Section 151 Officer”).

The Statement of Accounts is a long document and, in places, complex and technical. In our experience, this leads to many outside the finance function concluding, with some justification, that the Statement of Accounts is impenetrable to a non-finance professional. However, this can inadvertently lead to chief executives making the mistake of leaving the matter to accountants.

This is an error as it forgets that the Statement of Accounts is intended to provide publicly available information to demonstrate how the council has stewarded public money over the past financial year. It is important for chief executives and other working outside the finance function not only to be aware of this stewardship role but also become suitably confident in reviewing the Statement of Accounts to satisfy themselves that this public role is being fulfilled effectively.

The Statement of Accounts also sets out the council’s financial position and financial direction of travel, which is pertinent to its future strategy and decision-making. This is a matter that should be of importance to its leaders.

The mandatory inclusion of a plain language ‘Narrative Statement’ within the Statement of Accounts is an opportunity for the council to put across important messages about its finances and to clarify some of the more technical issues in the accounts. While this statement is signed-off by the chief finance officer and usually written by them, again, it is an aspect in which chief executives should take an interest.

This guide will not go into technical detail on every aspect of the Statement of Accounts, such a guide would run to many hundreds of pages of technical accounting narrative, and it is not the role of the chief executive to ensure the technical integrity of the document. Rather, it is written as a guide to what information is contained within the statements and how they can be read and reviewed without the need for a professional accounting qualification.

The guide includes examples taken from the publicly available Statements of Accounts from a variety of councils. However, whilst these examples are useful ones, their inclusion is not intended as an endorsement of these as model templates to be followed. Indeed, as you will see, the format and layout of the various financial statements is prescribed, and councils have limited flexibility on how they present the figures-based elements contained in the Statement of Accounts. Rather, the examples are used here to highlight what we consider is the key information contained within the various statements and to illustrate how they might be read and interpreted. It should also be pointed out that these statements are now some years old and so no inference or value should be given to the actual numbers, it is the formats and interpretation that we are interested in for this guide.

You will notice that there are checklist questions throughout the guide. These are designed to stimulate debate between the finance function and other senior officers in making the Statement of Accounts as user-friendly as possible in the way they are presented and published.

This guide has been written for what legislation calls “category 1” local councils and not smaller authorities with annual income and expenditure not exceeding £6.5m (smaller authorities are defined in the Local Audit and Accountability Act 2014 section 6 and have different accounting and audit requirements). Therefore, the guide is relevant for all district, county, and metropolitan local authorities, together with some larger town councils. Readers should also note that whilst the nature and format of local authority Statement of Accounts are similar throughout the UK, this guide is intended to cover England and Wales only.

Key points for consideration

- The Statement of Accounts is an important public demonstration of the effective stewardship over public money carried out by the council. Whilst there is lots of technical detail, is the overall impression one of effective, open, and transparent financial stewardship?

- Is the document published in a way that encourages non-finance professionals to engage with it? This is especially important for the narrative report section.

- Further to the above, is the narrative report viewed as a key corporate document in its own right? Is it considered as essential reading for everyone?

The purpose and legislative background to the Annual Statement of Accounts

The central role of the Statement of Accounts is to enhance the financial accountability of the council to those external to the council. They are prepared and published to give electors, local taxpayers, service users, elected members, employees and other interested parties clear information about the council’s finances over the previous financial year, setting these in the wider council context. They include information on questions such as:

- What did the council’s services cost in the year of account?

- Where did the money come from?

- Was this in line with the annual budget report setting out these issues for the forthcoming year? Are significant differences highlighted and explained?

- What is the value of the council’s assets – both in terms of the property, plant, and equipment it owns and in the council’s money reserves?

- What is the value for the council’s liabilities – both in the short term, e.g. monies owed to third parties such as suppliers and in the long term e.g. to members of the local government pension scheme?

The Statement of Accounts is a statutory document. The Local Government Act 2003 (section 21) enables the Secretary of State to issue regulation on the preparation and publication of accounts for local authorities, which is fulfilled by the Accounts and Audit Regulations 2015 (as amended). The requirements are that:

- Every council must prepare a statement of accounts in accordance with the Regulations and proper accounting practices (section 7(1)).

- These statements must include a narrative statement (also known as the narrative report) which comments on the council’s financial performance and the economy efficiency and effective in its use of resources over the financial year (section 8).

- The Responsible Financial Officer (the Section 151 Officer) must sign and date the accounts and so confirm that they are satisfied that they provide a true and fair view of the council’s finances (Section 9(1)).

- The council must ensure that there is a period of public consultation.

- After the period of public consultation, the Statement of accounts should be considered by Full Council, or a Committee of the Council, for them to discuss and approve the statements. The statements must then be signed and dated to this effect (section9(2)).

- The council must publish the annual Statement of Accounts, the narrative statement and the annual governance statement, together with any external audit opinion (reg 10(1)) by a specified date. This requirement is usually fulfilled via the council’s website, but some councils still provide paper copies to interested parties and for public use, possibly via the library service. Alternatively, where the Statements are not yet available for publication, an explanation of why the council has not been able to comply with this requirement must be published (sec 10(2)).

The legislative intention is to provide information in a format that is both relevant and useful to a wide range of potential readers and acts as a foundation to the annual Statement of Accounts being a corporate document rather than simply a financial one.

- What involvement do you as chief executive have in the preparation of the annual Statement of Accounts?

- Does the council treat the Statements in a similar manner to other council-wide publications, e.g. in their overall look and feel?

The form of the annual Statement of Accounts

You will have noted above that the Accounts and Audit Regulations Section 7(1) requires that the annual Statement of Accounts be prepared in accordance with proper accounting practices. This is defined as International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS), as applied to local authorities by the Chartered Institute of Public Finance and Accountancy (CIPFA) and the Local Authority (Scotland) Accounts Advisory Committee (LASAAC) in their Code of Practice on Local Authority Accounting in the United Kingdom. Further information on this is as follows:

- International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS). IFRS is the accounting rulebook used throughout the world. It is concerned with accounting and financial reporting for stock exchange listed companies to ensure that there is comparability in company accounts throughout the world, but the rulebook was adopted throughout the UK public sector from 2010/11. This presents a problem in as much as the nature and finances of a local council are different to a stock exchange listed company. Therefore, IFRS needs to be interpreted for use by local councils. This is undertaken by CIPFA/LASAAC.

- CIPFA/LASAAC is the body responsible for preparing, maintaining, developing and issuing a Code of Practice on Local Authority Accounting (technically known as a ‘SORP’ or Statement of Recommended Practice) that provides detailed guidance on the nature and form of the annual Statement of accounts. This body reviews changes in IFRS, together with wider aspects of local government finance and law and, after due consideration and consultation, issues Code of Practice updates as required. This is usually an annual undertaking. An important role of the external auditor is to ensure that the council has complied with the Code of Practice. In the event of non or limited compliance, this must be made clear in the Statements themselves and may result in a qualified audit opinion.

The fundamental problem that the Code of Practice seeks to address is that nearly two hundred years of legislation has established a finance system for local government which has its own unique set of rules. For example, the distinction made in local government between revenue and capital accounting is not a feature of company accounting. The published accounts therefore need to reflect both the IFRS rules (so the council can be compared with other entities) and the local government rules (so the accounts are usable by local authority decision makers). Effectively, this means that the Code of Practice attempts to combine and consolidate two accounting rule books, one professionally based, the other based on legislation, and the Financial Statements prepared and published by councils need to present the council’s accounts under both sets of rules.

It is a common complaint that this results in local authority Statement of Accounts being long and complex. Whilst this is undoubtably true, it must be pointed out that some local councils, particularly larger ones, are themselves complex in their finance and governance structures and therefore the Statement of Accounts needs to capture this complexity.

It can also be argued that users of local authority accounts have different and broader informational requirements to investors in a listed company. This is illustrated below:

|

Information requirement Stock Exchange Listed Company |

Information requirement Local Authority |

|---|---|

| How much is the company worth (its balance sheet value)? | Many of the assets in a local authority will never be sold (e.g. heritage assets, historic buildings) and the rules of local authority finance means that any assets that are sold produce capital receipts that in most cases cannot be used to finance revenue expenditure). This means the balance sheet value is not a key indicator of local council financial performance. |

| Has the company made a profit or loss? What implications does this have for its financial sustainability including future tax liabilities? | Whilst a surplus or deficit is shown in the accounts, this is not the same as any under or overspending against budget. Therefore, accounting profit is not an effective measure of local council financial sustainability. |

| What is the cashflow of the company? Can it afford to pay its bills? | Whilst cashflow and financial resilience is of the upmost importance to local councils, the nature of local authority finances means that the Cashflow Statement contained in the accounts is not the best representation of the council’s financial resilience. Councils generate most of their cash from reliable sources such as taxpayers and grant income rather than customers and so cash flow is not a crucial financial indicator as it is in a private business. |

Thus, all users should be aware that the council’s Statement of Accounts is prepared with a view to providing the information to both sets of questions. Once this is appreciated, the Statements are far from irrelevant, as some have suggested, you simply need to know where to look for the information you require.

After considering how the Statement of Accounts fits into the wider financial management process at the council, this guide will consider the main sections of the Statements and demonstrate that they do indeed provide much of the information users need to form an opinion on the council’s financial resilience and stewardship.

The Accounts preparation process

Accountants draw a distinction between financial accounting and management accounting.

Management accounting provides the organisation with the financial information that enables it to manage and control its day-to-day financial operations, e.g. the payment of bills, the billing and collection of income etc. The council will consider the overall management importance of such information and report those which are viewed as critical to effective service management. As such, non-cash transactions such as depreciation and valuation changes are not routinely reported to managers. For example, a change in the valuation of significant investment properties or assets that the council has designated for sale will be closely monitored, whereas the value of council’s historic civic hall might not appear at all in the management accounts.

In the private sector, much of this information is not shared externally, but in a local council management accounting is regularly reported to elected members in quarterly or monthly performance monitoring reports. Therefore, the public also has access to management accounting information as part of the council’s routine finance and performance monitoring process.

Financial accounting is the process by which the management accounting information is reformatted to produce the annual Statement of Accounts. These are designed for external users and so seek to represent the finances of the entire organisation, not just its day-to-day activities. Whilst much, if not all, the data used in the management accounting reports will be in the Statements, the Statements themselves are highly summarised, usually representing an entire year’s transactions in one just figure. They include financial matters that would not always be reported throughout the year as they are not of immediate concern to officers. For example, the Statements will consider the value of all the council’s property, plant and equipment and report whether this has gone up or down during the year.

Financial accounting is ‘accruals-based,’ meaning that all transactions that are incurred in the financial year are included within the accounts based on when the value of a transaction is given or received, regardless of whether the actual cash has been received or paid during the year. For example, the accounts will include the amount of council tax that is due from householders during the year, even if some residents have not got round to paying it yet. If all of what is due to the council is not paid within the year, the cash received will be lower than what is due, with the difference reported as a debtor in a note to the Statements. There will also need to be a provision for bad debts to allow for the risk that some people will never pay. Officers will closely monitor payments, chasing any unpaid bills as part of their debt management protocols.

Another important aspect of accruals accounting is the concept of the depreciation of assets. IFRS attempts to report the economic rather than the pure financial cost of running services for the year. Assets do not last forever and so the share of the cost of assets that have effectively been consumed within the year is included by way of a depreciation charge. For example, a council owned refuse freighter might be judged to have a 10-year useful life. Therefore, 1/10 of its purchase cost is added to the regular running costs of the council’s refuse collection service every year. The balance sheet will include the value of the freighter net of depreciation charges as part of the property plant and equipment balance.

Matters become a little more complex for some assets that gain value during the year, for example land, and even more complex when a building might appreciate in value at the same time as still having a finite useful life. Here, IFRS requires councils to report the current value of the asset, with any increases or decreases in value, net of adjusted depreciation, being recorded in a revaluation reserve.

Many councils do not provide accruals-based management accounts, preferring to report just financial commitments and then forecasting annual spending and income. This ensures that management accounting information is current and details the full cost of operating the service but is not on the same basis as that required under IFRS for the financial accounts.

This means that it is sometimes easy to conclude that what is important as a chief executive, or an elected member is the management accounting information and not the financial accounting. However, as we have seen above, the two sets of information are intrinsically linked (in accounting parlance, the financial accounts and management accounts should reconcile) and some councils who have taken their eye off the ball in terms of the preparation of their Statement of Accounts will soon discover that this also manifests itself in inadequate management information and control as well.

- How integrated is the council’s management accounting and financial accounting? Are they treated as two aspects of financial control by the finance function?

- Given that the main users of the Statement of Accounts are external to the council, how does the council ensure that they deliver the information that is required by such users in as user-friendly format as is possible?

Publication of the statement of accounts

The Accounts and Audit Regulations includes a deadline for the council to prepare the Statement of Accounts and submit these to their external auditors for review. Currently, this deadline is 31 May. It is considered good practice for these unaudited accounts

to be discussed at the Audit Committee, but there is no formal requirement for them to be approved by anyone other than the council’s Responsible Financial Officer. The unaudited accounts are frequently referred to as the ‘draft accounts’ although in fact they need to be complete and, to the best of the council’s knowledge, accurate before they are submitted for audit.

Councils usually publish the unaudited accounts on their website and so it is important that they are as complete and user-friendly as possible. The theory is that there should be few, if any, amendments required as part of the audit process.

This publication starts a formal 30-day period where local electors have the right to inspect the accounting records (including detailed transactional documentation) and to question the auditor or make formal objections on a matter of public interest or to report to the auditor if they consider that any item of account is unlawful. This effectively starts the external audit process.

The Accounts and Audit Regulations also specify that audited Statement of accounts should be published by the 30 September. However, over recent years, a significant number of audits have been delayed due to ongoing issues in the way that external audit is conducted for local authorities (the LGA’s Must Know guide on audit provides more information on the external audit process). Therefore, where it is not possible to publish the audited Statements by the deadline, the council must publish a statement giving reasons why this date has not been met. Once the audited Statements are available, they are formally approved (usually by the council’s Audit Committee) and are published on the council’s website together with the external auditor’s report and opinion.

The Role of the Audit Committee

The council’s Audit Committee has an essential role in overseeing the submission of accounts for audit and the work of the external auditor. It will liaise with the council’s Responsible Financial Officer to ensure that the unaudited Statements are prepared on time, and it is good practice for the unaudited statements to be discussed at the Committee in advance of them being forwarded for audit.

The Audit Committee will also receive information on the external auditor’s work programme for the year and receive audit opinions and recommendations as they become available. Finally, the Committee will receive and discuss the external auditor’s annual audit letter.

Whilst the Statement of Accounts is “owned” by the full Council, many councils delegate the approval of the audited Statements to the Audit Committee and so their role is vital in demonstrating corporate ownership and governance over the accounts preparation process and their subsequent audit.

Accounts – A guided tour

The format of the annual Statement of Accounts is largely prescribed by CIPFA’s Code of Practice and so the layout of the document is the same for every council. However, some of the reporting requirements vary with the type of local authority and its internal structure.

The annual financial statements will include the following sections:

- A narrative report.

- A statement of responsibilities. This summarises the council’s responsibilities in terms of its financial affairs and includes the certification signatures of the Responsible Financial Officer and whoever approves the accounts on behalf of the Full Council, usually either the Leader/ Executive Mayor of the Council or the Chair of the Audit Committee.

- Four “core” financial statements:

- The Comprehensive Income and Expenditure Account

- The Movement in Reserves Statements

- The Balance Sheet

- The Cashflow Statement.

- A series of notes expanding on aspects of the above core statements

- “Supplementary” statements as required depending on the nature and type of council, which might include:

- The Housing Revenue Account, where the Councils acts as a housing landlord.

- The Collection Fund for all billing authorities (those that collect Council Tax and Business Rates).

- Group accounts – that is a set of accounts that includes other entities under the council’s ownership or control, such as council-owned companies.

- A series of notes expanding on the supplementary statements

- The external auditor’s report and opinion

- A glossary of terms.

Councils that are administering authorities for the Local Government Pension Scheme will also produce accounts for the Pensions Fund, which are usually published alongside the council’s own accounts, even though it is not the council’s money.

Legislation also requires the council to prepare an Annual Governance Statement (AGS) and approve this in advance of the annual Statement of accounts. Some councils publish the AGS as part of the annual Statement of accounts, others publish it as a separate document.

The following sections will provide further information on the key components of the Statement of Accounts highlighting the information they can provide users.

The narrative report

The narrative report is probably the most important element of the whole Statement of Accounts document and is crucial as a demonstration of effective financial stewardship and accountability. It should be essential reading for everyone who wants to know about the council’s finances, set in the wider context and challenges faced at the council.

Whilst the Code of Practice sets out key areas which the narrative report should cover, the nature and layout of this section is left to individual councils. As such, this is the place where the council can exercise judgement and creativity in terms of how the information is presented.

The narrative report might include:

- Introductions by the leader/executive mayor and responsible financial officer.

- Brief details of the place the council serves.

- Links to the council’s other plans and vision statements, including the financial aspects of progress made during the year.

- A review of the council’s management structure, highlighting how the council controls and manages its finances.

- A review of the council’s financial performance for the year, including a summary of actual spending against the approved budget, where the money came from and where it has been spent (both for revenue and capital).

- Reference to the council’s key risks as contained in its risk management strategy.

- Reference to overall council performance in terms of service delivery as well as finance.

The narrative report is an opportunity for the council to produce something that can stand alone in its usefulness for council taxpayers and service users in terms of the council’s financial stewardship and accountability. Chief executives might wish to consider whether the council is making the most of this opportunity and there is nothing to prevent the council from publishing this element of the Statement of Accounts separately to maximise its potential audience.

There is also a glossary of financial and accounting terms at the back of the Statement of Accounts. This has wider use as it explains many of the key terminology and jargon used throughout council finance.

- Reflect on your latest narrative report. Does it read and look like a corporate document rather than simply a summary of the statement of accounts?

- Is it viewed by the council as an opportunity to demonstrate its effective stewardship of public money in an accessible manner?

- Has the authority considered publishing the narrative report separately to widen its potential audience?

- Does the glossary of terms help? Could it be written and published in a more accessible manner?

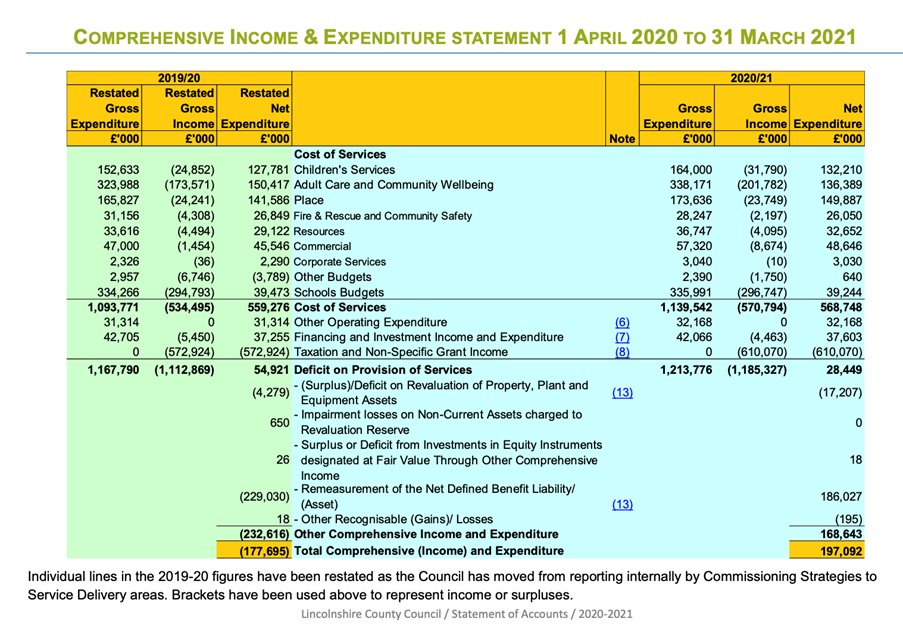

The Comprehensive Income and Expenditure Statement (the CIES)

This statement shows the accounting cost of providing services in accordance with the principles set out in the IFRS rather than just the amount paid for from taxation income. Whilst it does include all payments made to employees and external suppliers, it also includes non-cash transactions such as depreciation and accruals. It also shows the sources and values of all income due in the year, whether this has been received or not, for example any in-year gains or losses on asset and pension fund valuations. The CIES is the nearest equivalent to the profit and loss account in Company accounts although it cannot be thought of in the same way.

It might be useful to consider the CIES in three parts:

Part A: The CIES starts by detailing the economic cost of the council’s services. Therefore, gross expenditure includes non-cash items such as depreciation charges on capital assets as well as cash items such as employee costs, supplies and services and support service costs. Gross income represents fees and charges income and any specific grants paid to the council, for example the Dedicated Schools Grant.

- Compare the various figures between years. Are there any significant changes in expenditure or income? Check the Narrative Report or the notes for an explanation for this.

Part B: The CIES then sets out what might be considered as council-wide income and expenditure such as investment returns, debt servicing costs and a summary of the income raised through taxation such as Council Tax, Business Rates, and general government grants. This element of the CIES is linked to the Collection Fund for billing authorities (see below). As shown in the illustration, there will be notes that break these figures down into their individual parts. You may want to skip directly to these if you want further details.

- The performance of council investments and the cost of its borrowing can be key figures. Are the figures shown here in line with the expectations set out in the Treasury Management Strategy? Further information on performance should be contained within the Treasury Management Annual Report.

Part C: The latter part of the CIES details what councils might consider to be non-cash gains and losses. This includes any surplus or deficit on the revaluation of its property, plant, and equipment and on the valuation of its pension liabilities. As is illustrated below, such revaluations can be highly significant, and potentially volatile, in terms of their effect on the overall Statement. This means that whilst, in accounting terms, Lincolnshire County Council was reporting a deficit of just over £197.092m in the year, this was largely due to a downwards revaluation in their pension fund of £186.027m. Therefore, care must taken over the reporting of the “bottom line”.” It certainly is not the same as an over or underspend against budget (budget over and underspends are summarised in the narrative report).

Alongside the CIES, a note to the accounts known as the Expenditure and Funding Account (or ‘EFA’) provides another, more user-friendly way of looking at the council’s expenditure and income (see below).

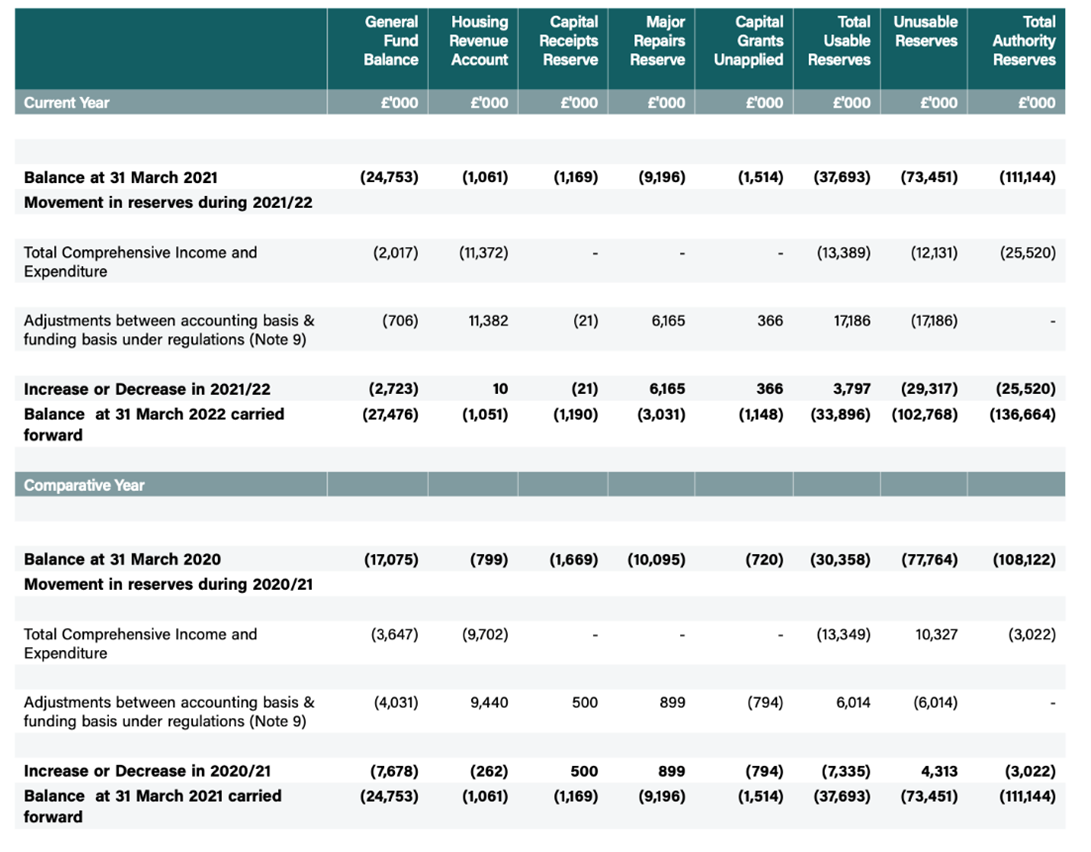

The Movement in Reserves Statement (the MiRS)

The Movement in Reserves Statement (MiRS) shows how the council’s various reserves have changed over the year of account, with the movements in each type of reserve broken down over gains and losses.

An illustration of this important statement is provided below. This statement provides two full years’ worth of information.

Source: North Kesteven District Council

The level of reserves held by the council is an important figure and so it is essential to realise that this statement is the IFRS based view of reserves and so the Total Reserves column is not the same as the council’s cash-backed reserves. This is because the MiRS reports two types of reserve:

- Usable reserves: These reserves are cash-backed and are available to the council to finance its activities in future years. The MiRS distinguishes between revenue and capital reserves; the latter can usually only be used for capital purposes.

- Unusable reserves: These reserves are created by movements in the value of the council’s assets and liabilities. Thus, they are not cash-backed and so are not available to the council to finance future activity. This will include asset revaluation reserves and pension reserves.

This presentation between usable and unusable reserves is one of the features that emerges from the need to reconcile IFRS and English local government concepts of accounting, as discussed above.

The MiRS shows whether reserves have risen or fallen in total during the year and usable reserves are further broken down in the MiRS to demonstrate the various legal requirements on the use of council finance. Thus, HRA balances are separate from General Fund, together with capital reserves separated from revenue ones.

The General Fund balance includes reserves that have been earmarked to specific projects or activities as well as the general fund working balance. There will be notes that will further breakdown these figures elsewhere in the Statement of Accounts. These notes will be considered in more detail later in the guide.

- Have reserves (especially the General Fund balance) increased or decreased during the year? Is this in line with the Council’s Medium Term Financial Strategy expectations? Is this consistent with the council’s overall objectives and policy decisions?

- Is the level of general fund reserves above the minimum level agreed as part of the annual budget report and does the level of reserves demonstrate that the council is financially sustainable and resilient into the medium-term?

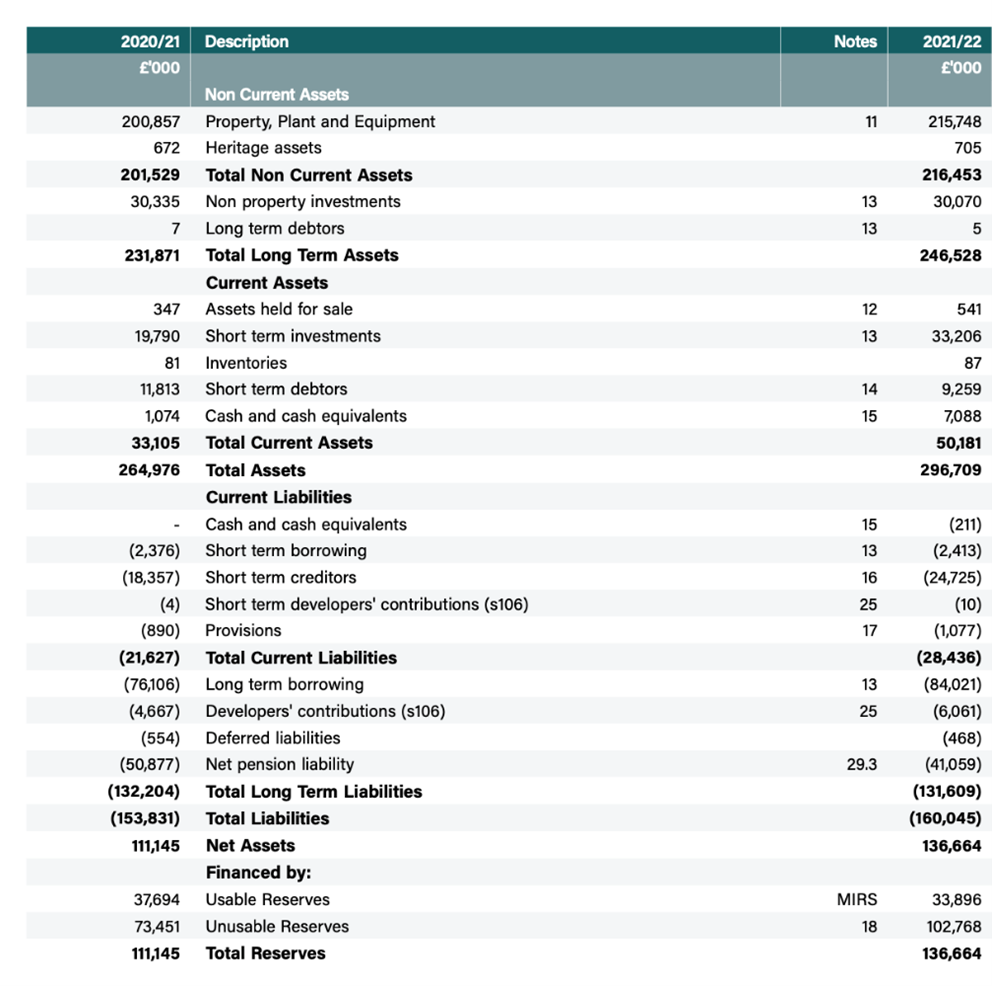

The Balance Sheet

The Balance Sheet is a financial snapshot of the council’s assets and liabilities as at the 31 March (the balance sheet date) every year.

Assets and liabilities are separated into current and non-current:

- ‘Current’ usually means that the transactions making up the balance are owned / owed within 365 days. For example, the value of inventories (e.g. stores at the council’s depots such as paint, road salt etc.). These change regularly and so the council will undertake a stock take on 31 March to formally value the inventories as at the balance sheet date.

- Non-current are those assets and liabilities that are owned / owed over longer than 365 days (e.g. long-term debtors such as loans to other public bodies or, in some cases, council mortgages that still have some of their original term outstanding.

In fact, the terms ‘short term’ and ‘long term’ are often used instead of ‘current’ and ’non-current.’ Although we use these terms freely in everyday speech, in an accounting context they always refer to the next 12 months (current; short term) and periods beyond 12 months (non-current; long term).

The value of the council’s property, plant and equipment is likely to be a significant figure on the balance sheet. There will be a note providing detail on this which we will consider below. However, in general, this balance represents the current replacement value of the council’s operational buildings (e.g. the Civic Centre). Heritage assets will include assets that are held by the council for civic and ceremonial functions and might include non-operational historic buildings such as windmills, civic regalia, and art. These are likely to be of significant age and it may be that they are valued at a proxy amount rather than their historic cost if this information has been lost over time.

The following example illustrates the connections between the Balance Sheet and the Movement of Reserves Statement considered in the previous section.

Source: North Kesteven District Council

The Net Assets figure is effectively the balance sheet value of the council and, on the “other side” of the balance sheet, you can see the usable and unusable reserves balancing the accounts. Most councils have a positive balance sheet value, which means the value of assets exceeds liabilities, but this is largely because they own assets which have accumulated value over time. To realise that value the assets in question would need to be sold, which in the case of many assets is not practicable. You will note that these reserve balances are the same as in the Movement in Reserves Statement as discussed above. Thus, the balance sheet balances!

For those familiar with company accounts, the balance sheet format is very similar, although figures for Reserves take the place of Profit & Loss Account balances and shareholders' equity.

The cashflow statement

The cashflow statement shows the changes in cash and cash equivalents, which are defined as short term highly liquid balances that are readily converted into cash, e.g. the council’s bank balances.

This statement is of critical importance in the private sector as it demonstrates how the entity is generating cash, which is essential to enable bills to be paid and, thus, avoid insolvency. (Another word that is often used is ‘liquidity’- the ability of an organisation to finance its activities from its own cash). The cash flow statement is also of general interest in showing where a council gets its cash from and how it is disbursed. Cash management at the council is extremely important in terms of making sure that those who owe the council money, particularly Council Tax and Business Rates taxpayers, pay on time and in full, and that the council can pay its own bills, such as the monthly payroll. However as long as people pay their taxes and the government transfers grants according to the scheduled timetable, councils are not usually short of cash. Insolvency is not generally a concern in council financial management. Ironically, while the media persist in calling councils ‘cash strapped,’ this is the one financial problem that councils in general do not have. It is more accurate to say councils are under-funded.

The notes

The four core financial statements are supported by a series of notes that provide further information on the account balance. The notes provide additional narrative detail and often breakdowns of the figures in the balance sheet, so they can be of greater interest to readers of the accounts than the main statements. In general, these notes either breakdown the account balance into its constituent parts and / or provide further narrative explanation on the nature and purpose of the account balance. They provide more detail in relation to many of the figures in the core statements.

- It is useful to keep an eye out for note numbers as you review the core financial statements. If you want further information about the account balance, turn to the relevant note number. Then turn back to the core statement and continue reading!

The following paragraphs provide further information on some of the more important notes, some of which can be challenging to read due to their technical nature.

The Expenditure and Funding Analysis (EFA): as explained above, the Statement of Accounts represents the council’s finances under both accounting (IFRS) and legal rules. This note demonstrates how the two rulebooks interact with each other and sets out the various adjustments that need to be made when switching between the two rulebooks. Whilst it is highly technical in nature, it does provide a useful tool to link the IFRS based accounts with the management information that is reported to the council during the financial year. A central responsibility of the external auditor is to satisfy themselves that the council has complied with its legal requirements to present the accounts in accordance with proper practice and so auditors will carefully review this analysis as part of their work.

Property, plant, and equipment (PPE): The value of PPE is likely to be one of the largest, most material items on the balance sheet. Therefore, the financial statements provide significant detail on the council’s PPE in this note. The note not only provides a breakdown that explains the overall balance sheet movement but also further information about any capital commitments the council currently has at the balance sheet date.

Over the past few years, the valuation of assets has become a significant issue in many councils. This is because of the increased focus on such valuations by external auditors due to the material nature of these figures on the council’s balance sheet. However, many of these assets will be directly operational at the council and so will not be for sale in the foreseeable future, if ever. This means that the balance sheet value of such assets is not considered to be the most important figure for management purposes. On the other hand, it is one of the largest figures on the balance sheet and so it is important that the finance department can provide external auditors with the assurance they need that valuations etc. are true and fair.

It has been argued by some in local government that these balance sheet valuations are largely irrelevant and can be responsible for the delay in the publication of the Statements as external auditors confirm such balances. Whilst this might be true for assets that the council has no intention to dispose of or sell (parks or schools, for example), they become more relevant for assets that might be sold in future years or are only held for income generation or more commercial purposes, for example leisure facilities. The finance function must maintain up to date records of all capital accounting transactions, including valuation and annual depreciation charges, to satisfy the reporting requirement in the balance sheet and related notes as well for the external auditor.

Investment properties: These assets are held by the council either to generate income and / or for capital appreciation (e.g. industrial units rented out, county farms etc.). As such, these assets are of greater importance to the council’s finances than those held for operational reasons. The note provides a breakdown of the current value of such assets. The fluctuation of these values is more important to the council, especially if it wishes to sell the assets in the near future and in some cases might affect the longer-term resilience at the council especially if the council has borrowed to finance these assets in the past. Whilst the acquisition of investment property has been a controversial issue over recent years, large numbers of councils have such properties, in some cases assets that have been in public ownership for centuries.

- Investment assets can be a critical area for councils who have significant investment property portfolios. Are there any large fluctuations in the value of these assets? What does this tell you about the longer-term financial viability of the council’s holdings?

Financial instruments: This note provides details of the council’s borrowings and long-term financial liabilities, including leasing and any commitments made under the Private Finance Initiative. PFI (Private Finance Initiative) schemes will also have a further note providing full information on the council’s commitments under such deals. All of these are valued at “fair value” as defined under the rules of IFRS. For most purposes you can think of ‘fair value’ as equating to the value that assets and liabilities have in the current market – although accountants and auditors will rightly declare that this is an over-simplification. This can be a highly detailed and technical note, but it considers the council’s exposure to financial volatility from such transactions. Therefore, there are sections considering the council’s overall exposure to risk and describing the council’s approach to mitigating and managing such risks.

- Many of these issues will be covered by the council’s Treasury Management Strategy. Review this note in the light of the Strategy and consider whether the information and council’s overall progress in these areas is consistent.

Reserves and Balances: The usable (and unusable) reserves balances in the MiRS and Balance Sheet will be broken down into their constituent parts in a series of notes. This is one of the most important notes in terms of financial accountability and transparency as the note that provides more detailed information on the purpose for which the council’s earmarked (also known as specific) reserves are held.

The note will also include narrative information on the purpose of the reserve balances held at the council. The note enables the reader to trace movements in and out of reserves over a two-year period.

The council will have a reserves policy which will detail how earmarked reserves are created, used, and closed and this note should demonstrate compliance with this policy as at the opening and closing balance sheet dates. In general, there are three types of earmarked reserve:

- Those that are earmarked (or ring-fenced) by law. For example, schools’ balances, public health grant balances and in the Housing Revenue Account. These reserves are cash-backed but can only be allocated in accordance with legal or other external regulations.

- To smooth uneven or volatile payments. Some council expenditure is not even over financial years and so the council might seek to smooth the budgetary impact of such expenditure through an earmarked reserve. For example, councils who have all out elections every fourth year might contribute to an elections reserve in the three fallow years and then utilise that reserve to fund the election year. Similarly, councils may use a reserve to provide funding for unexpected or one-off expenditure, for example a transformation reserve to fund the one-off costs of various projects designed to transform the council’s service delivery.

- To “save up” for projects or costs that are anticipated in the future. For example, an equipment replacement reserve.

As such this is an important note, and a review should allay any suspicion that the council is accumulating money in its reserves for no good reason. Therefore, it is essential that the openness and transparency of this note is reviewed wider than the finance function.

- Consider the appropriateness of the reserves held by the council. Earmarked reserves should be held for some future purpose, either to contribute to the cost of a particular scheme or project planned in the future or to protect the council against financial volatility, for example anticipated reductions in government grant funding. Does the note demonstrate that the council’s reserves are indeed held in such a manner.

- Is the title of the reserve and the narrative explanation in the note suitably open and transparent as to the nature of the reserve?

- Are there any reserves that are held but have not moved at all over the two-year period? Many councils have reserves to smooth cyclical costs, for example, the cost of elections. It is, therefore, normal for such reserves will be increased during non-election years and then spent during the election year.

- Generally, does this note contribute to open and transparent financial reporting principles?

Provisions Accounting rules require all entities to be prudent in the way that they report their finances. Thus, if there is a possibility that a financial expense will be incurred in the future which is uncertain in terms of timing and cost, the Statement of Accounts will set aside (provide for) an estimate of this amount as soon as it becomes likely to be incurred. For example, despite its best efforts, it is usually unlikely that the council will recover 100 per cent of the council tax and business rates owing in the financial year. Therefore, the council will make an estimate of the percentage amount that is considered doubtful and provide for this amount in a provision for ‘bad’ or doubtful debts.

If the council considers that it is likely to incur a significant cost, possibly due to an insurance claim, the council will also seek an estimate of the potential cost of the claim (whilst taking the advice of its insurers in terms of an admission of liability) and provide for this some in an insurance provision. The claim is then settled via this provision or indeed the provision is released back into the council’s general reserves should the claim be unsuccessful.

The Capital Financing Requirement. The CFR shows how the council’s capital expenditure is being financed. Whilst technical in nature, the bottom line of the CFR shows the underlying need to borrow to finance capital expenditure and significant upwards movement of the underlying need to borrow as disclosed in the note might be of concern to the council’s overall financial sustainability into the future. The council’s Treasury Management Strategy and Capital Strategy will provide further information on the council’s underlying need to borrow for capital purposes.

Contingent Liabilities A contingent liability is defined as a cost that may arise depending on the outcome of a specific event. It is therefore a possible obligation which may or may not arise as future events unfold. Whilst these amounts are not recorded in the council’s accounts, following the accounting principles or prudence, if the council becomes aware of any such contingent liability it must disclose the fact in a note. For example, many councils who were insured by Municipal Mutual Insurance limited, which ceased to write new insurance policies in 1992 and subsequently became insolvent, are still potentially liable for any outstanding insurance claims. This is disclosed as a contingent liability.

The distinction between a provision and a contingent liability is that provisions are liabilities that are known about and can therefore be estimated, but the timing and exact amount are not known. The provision in the accounts sets aside money for that purpose. A contingent liability is a significant (or, as auditors say, ‘material’) item which may or may not arise, but because it has a potential future impact on the council’s financial position, needs to be reported.

By their very nature contingent liabilities are specific to an individual council’s circumstances and can be financially significant but because there are currently no financial transactions involved these sums are unlikely to be included within the council’s approved annual budget. Therefore, it is important to read this note to understand if the council might be subject to any such financial claim at some point in the future.

Pension schemes: These notes provide information on the various pension schemes that council officers are members of. This might include:

- The Local Government Pension Scheme (LGPS). This is the main pension scheme that covers council officers. It is a defined benefit scheme, meaning that members earn a pension based on their years of service and salary level. The individual officer contributes to the pension scheme through deductions of salary (defined in law) and the council adds employer contributions from its resources. These resources are invested to make a return. Every year, the council’s actuary provides a review and revaluation of the LGPS, which forms the basis of this note.

- Teachers’ Pension Scheme (TPS). This scheme is administered by the Department of Education and the Statement of Accounts details the various transactions made by the council in their capacity as an education authority. Whilst the scheme is technically a defined benefit scheme, the scheme is unfunded, meaning that it is not backed by investments. Rather pensions are paid as they become due from national taxation income.

- National Health Service Pension Scheme (NHSPS). Most staff transferred to local councils from the NHS as part of Public Health and Children’s Services reforms have remained part of the NHSPS and so details of this pension scheme are contained in the financial statements. Like the Teachers’ Pension Scheme, this is an unfunded defined benefit scheme, but the accounts will include the various day-to-day transactions paid by the council during the year.

- Fire-Fighters’ Pension Scheme. This is a further defined benefit unfunded scheme which is administered by some county councils where there is a separate Fire Authority.

In addition, pension fund administering authorities will publish the accounts of the Pension Fund they manage alongside their own accounts. The pension fund administering authorities are county councils, London boroughs, some county unitaries and some metropolitan districts.

Pooled budgets: This note is required by law where the council has entered pooled budget arrangements with the Health Service, originally as part of the Health Act 1999. The note details all financial activities undertaken by the council as the host authority for pooled budgets and shows the annual surplus or deficit on a range of care activities operated under pooled arrangements.

Members’ Allowances: This note is required under law and details the various allowances provided to elected members. Whilst in relative terms this note deals with a small sum of money it can on occasions cause local interest. The inclusion of this note is, of course, a contribution to the openness and transparency of the council’s democratic process.

Officers’ Remuneration: The note shows the total number of staff employed by the council whose actual remuneration exceeds £50,000 per annum, shown in £5,000 bands. Remuneration includes gross salary, expenses, and the monetary value of any benefits in kind. It also includes the value of any termination packages. The Accounts and Audit Regulations (England) 2015 required councils to disclose individual remuneration details for senior employees who have responsibility for the management of the organisation or who direct or control council activities. This is reported via job title, apart from the most highly paid officer (usually the chief executive), who is specifically named in the list.

The Supplementary Statements

Some councils have supplementary activities which require their own separate accounting statement, either by statute or as a response to the accounting code.

The Housing Revenue Account (HRA)

For councils which are landlords, the annual Financial Statements include separate HRA accounts which show the economic cost in the year of providing housing services as defined under IFRS.

Councils charge housing rent in accordance with regulations to cover some, but not all the economic cost of providing housing and there is also a movement on the HRA Statement which considers the increase or decrease in the year on the basis for which rent is raised and spent. It concludes with the HRA reserve balance.

It is important to be aware that the core financial statements include both General Fund and HRA transactions and so links can be seen between these are the core financial statements. For example, the HRA reserve is also disclosed in the Movement in Reserves Statement.

The statements also include several notes detailing financial and non-financial information, for example, the number and types of dwelling in the housing stock, together with their value and the current level of rent arrears.

The Collection Fund

The Collection Fund councils that collect business rates and council tax on behalf of other local authorities (metropolitan and unitary councils as well as district councils) account for the inflow and outflow of such taxation income through their Collection Fund. The tax collecting authorities are known as ’billing authorities’ and the councils which draw income from the Collection Fund are ’precepting authorities.’ In effect, the Collection Fund is an agent’s statement that reflects the statutory obligation to bill council tax and Business rates and then to distribute (precept) the sum required to the various tiers of local government represented on the bill and, in the case of Business Rates to and from central Government.

The statement shows the various transactions in relation to the collection of council tax and business rates and the amounts paid over to the various parties involved. Note that for parish areas, the various parish precepts form part of the overall district council sum in the Collection Fund accounts but are paid over to the various parishes by the district council. This can be seen in the CIES.

The Group Accounts

The CIPFA Code of Practice requires the production of Group Accounts where a council has material financial interests and a significant level of control over separate entities. The most common such entities are companies which are wholly owned by the council or in which it has a ‘material interest.’ The aim of these statements is to provide an overall financial picture of the council’s activities where the council has chosen to organise itself in a way that separate legal entities (such as council owned companies) are responsible for providing such activities.

Every year, the council is required to review its operational activities and consider whether relationships with external companies and organisations are sufficiently close to require their inclusion in group accounts. Those councils who have trading companies, including housing companies, are likely to have group accounts where others may not be required to prepare them at all.

Summary

The annual Statement of Accounts is by its very nature, a set of long and technical documents. However, they are an important part of the council’s overall stewardship and accountability framework. Therefore, whilst the council’s responsible financial officer and the finance department will take the overall lead in preparing the statements, it is important that the chief executive takes an interest, not only in what the accounts show about the council’s financial health but also to review and ensure that they fulfil their accountability role to an external audience, especially local taxpayers and residents.

In summary, this guide sets out the following key questions for chief executives to consider, alongside others that are included within the text:

- Has the council considered how best to write those sections of the annual financial statements where the authority has control over to ensure that they are useful and readable to a non-finance audience?

- Has the council considered whether financial accountability might be enhanced by including explanation and graphics in the financial statements rather than simply reporting the various accounting statements?

- Do the accounts paint the picture of a council that is on top of its finances?

- Is key financial information easy to find or is it buried in the accounts?

- Have there been any significant changes between years? Can you see these in the annual financial statements? Are they sufficiently explained?

- Are any movements, particularly for investments, borrowing and asset values consistent with the council’s wider strategies, especially the Treasury Management Strategy?

- Where are the accounts published? Can a simple search on the council’s website take a user straight to them?

About the author

Ian Fifield CPFA has over 30 years experience in and around local government finance, with experience both as an auditor and a finance officer. For the past 12 years, he has provided training to local government elected members and officers in financial management and governance.