Introduction

At the top of a local authority, as chief executive, Leader or elected Mayor, you need assurance that what you are seeking to achieve is indeed being delivered to its optimum whilst securing and demonstrating the most efficient and effective use of public funds.

The council will have a plethora of policies, procedures, strategies, objectives, plans and performance indicators, but how do you get the assurance that these are working, delivering the right results, and driving continuous improvement? How are you assured that the arrangements for internal control, risk management and general governance are in place, adequate and effective; the arrangements that inevitably support and enable the success of the council and meet statutory obligations?

It is a management responsibility to deliver the objectives set by the council and be held to account for doing so, but we know that despite best efforts and good intentions, that responsibility does not always achieve its intended outcomes, sometimes with quite serious and damaging implications.

There is however a function that exists, often under-used, under-valued and mis-understood, that can make a significant contribution to the assurance you need. It can be influential in promoting organisational improvement, enhancing, and protecting organisational value, providing valuable insight, and demonstrating to the public that there has been the proper use and accounting for public money.

The audit function, both internal and external, is there to help do this. Whilst both work within frameworks guided by legislation and professional standards and practice, there is significant scope to ensure you maximise their contribution to your council’s success and demonstrating public accountability.

This ‘Must Know’ guide covering Working with Auditors provides information and practical guidance to help you ensure this valuable resource is maximised.

The guide sets out the status, legal and best practice frameworks and roles and responsibilities of both sets of auditors. Understanding this is important to ensure the greatest value is derived from the auditors and what the authority’s responsibilities are to achieve it.

Internal audit

Internal Audit is the council’s own team of officers or contractors, working within the council, responsible to management and overseen by the audit committee.

Before exploring how to get the best from internal audit (IA), it is important to understand what it is, what it does and the legislative basis on which it works.

Legislative basis of Internal Audit

The Accounts and Audit Regulations 2015 (SI No. 234), Part 2 (Internal Control), Section 5 states:

Internal audit

5. (1) A relevant authority must undertake an effective internal audit to evaluate the effectiveness of its risk management, control, and governance processes, taking into account public sector internal auditing standards or guidance.

(2) Any officer or member of a relevant authority must, if required to do so for the purposes of the internal audit -

(a) make available such documents and records; and

(b) supply such information and explanations;

as are considered necessary by those conducting the internal audit.

(3) In this regulation “documents and records” includes information recorded in an electronic form.

Within the legislation is the requirement for an IA function to adhere to guidance. The Public Sector Internal Audit Standards (PSIAS) are referenced in the legislation but there is also additional best practice that needs to be considered, most notably CIPFA’s Statement on the Role of the Head of Internal Audit (HoIA).

The key and critical elements of the legislation and guidance are encapsulated in the guiding definition of IA within the international standards for IA practice:

Internal auditing is an independent, objective assurance and consulting activity designed to add value and improve an organisation’s operations. It helps an organisation accomplish its objectives by bringing a systematic, disciplined approach to evaluate and improve the effectiveness of risk management, control, and governance processes.

Public Sector Internal Audit Standards 2017

This definition supports the simple mission of IA:

To enhance and protect organisational value by providing risk-based and objective assurance, advice, and insight.

Public Sector Internal Audit Standards 2017 *

* The Global Institute of Internal Auditors issued revised standards in January 2024 for implementation in 2025. Revised Public Sector Internal Audit Standards will also be issued.

As can be seen, there are important aspects of the IA function that set it apart from other management support functions in a council. Emboldened words and phrases are of particular significance and will feature throughout this guide.

The reason for setting out this legislative context and guidance is that to get the best from the relationship with IA, it is critical to ensure the there is an organisational culture that that supports and encourages openness, transparency, and supportive challenge. Without that culture in place, and demonstrated ‘from the top,’ it will be harder to reap the benefits of an effective IA function.

Whilst an IA function is mandatory for a local authority, how and from whom it is provided is not prescribed and a mixed economy of provision has evolved. This ranges from an entirely in-house, directly employed function through to the fully outsourced with shared services, consortia, and co-sourced arrangements in between. Some practical differences and considerations regarding who provides the IA function are set out in Annex 2.

The Head of Internal Audit (HoIA)

An important element of the IA function is the role of the HoIA. Linked to how the IA function is provided, the HoIA may be a directly employed officer or an employee of a contracted provider. Whatever the HoIA’s employment status is, that individual is bound by the same professional responsibilities.

The Head of Internal Audit (HoIA) is perhaps unique in being required to operate independently, report in their own name to relevant committees and chief officers, have unfettered access to the chief executive and the audit committee and therefore have a status in the organisation different to most other senior roles.

The term HoIA is used generically in the Public Sector Internal Audit Standards (PSIAS), but the individual may have a different job title. Whatever they are called, there must be one individual who is responsible for the IA function and specific professional responsibilities required by the PSIAS.

The HoIA is providing a service to management and as such the key relationships are with the chief executive, the statutory chief finance officer and monitoring officer, the senior management team, wider management across the organisation and the audit committee. (The role of the audit committee and members more widely in working with internal audit and external audit is not specifically covered in the guide. Annex 3 does however provide useful information in this regard).

Organisational responsibility, accountability and culture

This is critical factor for the success of any organisation. Not having the right culture, one that facilitates, enables, and ensures clear responsibility and accountability, an organisation is at a higher risk of failure in some shape or form. It is a common theme in organisational failures across the public and indeed private sectors, that cultural problems and poor governance are the root cause.

This culture must be driven ‘from the top’ and having an effective IA function that is fully and openly engaged and has the appropriate status and profile in the council will demonstrate and support that culture.

Working with Internal Audit

Internal Audit, by its nature has a broader and more flexible remit than external audit, albeit still needing to abide by the professional standards for internal auditing.

This section highlights how internal auditors work and therefore how to work with them to greatest value.

As previously mentioned, a corporate predisposition to adopt an open and transparent culture, that demonstrates public accountability and seeks to constantly drive improvement through engaging with auditors, inspectors, and regulators, will go a long way to getting the greatest value from internal (and external) audit. An underlying culture to encourage challenge is not only a healthy one, but it also provides a solid basis for IA to be effective.

The extent to which IA can impact relies on such an organisational culture. IA is most effective when ‘allowed in,’ openly and at all levels across the organisation. Although the HoIA has specific responsibilities and IA is indeed empowered through the provisions of legislation to have access to anyone and anything in the fulfilment of their role.

As a reminder, the Accounts and Audit Regulations state that:

Any officer or member of a relevant authority must, if required to do so for the purposes of the internal audit -

- make available such documents and records; and

- supply such information and explanations;

as are considered necessary by those conducting the internal audit.

Ideally, the HoIA should never have to ‘remind’ management of their legislative rights of access.

In basic terms the chief executive / ‘management’ are seeking independent and objective assurance from IA on the effectiveness and efficiency of the council’s internal control, risk management and governance arrangements that will support and enable the efficient and effective delivery of objectives. This assurance is delivered through planned and responsive work, advice, and support.

Internal Audit planning

So, what does IA actually do?

Although local government and indeed all businesses are constantly changing, responding to external pressures, managing difficult financial positions, and navigating various political and economic challenges, they are, or should be, underpinned by a core framework of effective and efficient internal controls, risk management and governance.

Good practice is that IA set out their intended coverage in a plan, to deliver that independent and objective assurance through the deployment of their resources. That plan is usually for the financial year, but may be more of a rolling plan, broken down into quarters or indeed take a longer-term perspective. However the IA plan is formed, it will be significantly influenced by the strategic and operational context of the council and therefore how IA construct their plan is key.

As the professional standards and guidance state, IA work is risk-based, or risk influenced and must therefore be cognisant of existing and future matters that threaten the delivery of objectives. Auditors do not however have a crystal ball, hence why engagement with senior management across the authority is so important, on a continual basis, and not just for the purpose of setting the annual plan.

The IA plan should therefore be determined via a consultative process. Whilst the responsibility for determining the plan ultimately rests with the HoIA, the most effective plans are co-designed.

There are a number of facets to how the IA plan is determined. A typical format for the IA plan is included as Annex 4 to capture the areas of possible coverage but also to demonstrate their link / contribution to the key risks, strategies, policy areas and objectives of the council.

In simple terms the IA plan is formulated through:

- Consideration of the strategic and operational risks, concerns, and issues – as set out in risk registers.

- Consideration of historical and topical issues (local and national) as well as horizon scanning to identify any major issues that might affect the controls, risks, or governance of the council.

- Consideration of issues to provide specific assurances to the statutory S151 Officer in meeting his/her statutory responsibilities (predominantly the audit of the major financial systems and processes of the authority).

- Consultation with the senior management team and each directorate management team responsible for the delivery of services, with reference to their business plans, risk registers, external relationships / contracts etc.

- Internal Audit’s own cumulative knowledge and experience (supplemented by the sharing of intelligence, good practice, and experience between HoIAs, locally, regionally, and nationally).

- Consultation with the audit committee that has responsibility for overseeing delivery of the work of Internal Audit, to ensure any of their concerns are considered, and also being assured of the audit planning process itself.

As stated, the HoIA has the responsibility for the plan. Management and the audit committee can clearly have input to it and approve it but cannot direct it. This can sometimes be an area of tension between ‘management’ and the HoIA. It is important that the independent status afforded to the IA function and the HoIA personally, is respected. It is indeed important for the chief executive and audit committee to be assured that the work of IA has not been subject to inappropriate influence, either to do something or not do something. This unfettered independence is critical for an effective IA function and should be supported and demonstrated from the senior management team and across the authority.

A key part of the audit planning process is to ensure sufficient overall coverage is provided across the council to enable the HoIA to give an annual opinion on the effectiveness of the council’s internal controls, risk management, and governance arrangements. There needs to be sufficient work across those areas upon which to base each of these opinions.

IA is an internal control in its own right. Ensuring that the organisation has a good awareness of the existence, role and remit of IA does provide an over-arching element of control. It is useful for all staff to be aware of the potential for their area of responsibility to be subject to internal audit.

There is a dichotomy, however. Good practice is that IA is risk based and therefore its resources directed to the highest areas of risk – the ‘red’ risks on risk registers being an obvious driver. However, ‘green and ‘amber’ areas have the potential to become ‘red’ if not adequately managed. The resources available to the HoIA are limited and so this places a responsibility on the HoIA to carefully consider how to deploy resources into some of those ‘green’ and ‘amber’ areas – a sort of ‘diagonal slice’ through the organisation. This can be very effective to give assurances with a broader perspective, promote IA across the council and to provide the HoIA with a more holistic view of the organisation, and how well governance and accountability responsibilities are understood in all parts of the organisation. A rich base to use to provide assurance should be an aim of the IA plan.

It is almost inevitable that despite the supporting culture of the council, the resources available to the HoIA are going to be under constant pressure and may be reduced alongside other ‘back-office’ services to meet budget saving targets. This creates the need for the prioritisation of where IA resources will be deployed and the expectation of ensuring those limited resources are used as efficiently and effectively as possible – a core responsibility of the HoIA.

The planning process will almost certainly identify more potential areas for IA to review than the resources will allow. The professional judgement of the HoIA is therefore key to determine a plan that includes sufficient coverage to base an opinion on the controls, risk, and governance arrangements, but also one that is broad and deep enough, through the ‘diagonal slice’ approach, to facilitate that whole organisational perspective. There is an inherent risk of IA resources only being focussed on the red risks and ‘big ticket’ issues.

Councils that take their eye off the basics do so at their peril, and so it is entirely appropriate for some IA coverage to be focussed in areas to prevent red risks appearing. It is a delicate balance the HoIA needs to consider carefully and explain to senior management and the audit committee how that coverage will provide the appropriate assurance.

Of particular interest for the senior management team is, if IA cannot resource the required assurance activity fully, where will assurance come from?

It is the role of the management to implement and maintain an effective framework of internal controls, risk management and governance. Care needs to be taken that IA does not inadvertently ‘slip’ into this management space (many internal audit teams were redeployed to help with the response to the COVID pandemic and in exceptional circumstances like those it is entirely appropriate to utilise the organisational knowledge of IA to assist management). Being ‘internal,’ and perhaps particularly for an in-house IA team, the HoIA needs to safeguard being used or tempted to help management in a way that may compromise IA’s independence. It is a difficult balance and judgement. The HoIA will clearly want and need to add value, but not at the expense of professional independence and objectivity. (See Annex 5 for information on the Three Lines Model that may be useful to define and guide the key levels of responsibility).

In circumstances where there may be a clear gap in management capacity or an urgent need, very careful consideration should be given to whether it is appropriate for IA to step in. Safeguards can be put in place to allow this, such as a ‘Chinese wall’ in how a piece of IA work is managed within the IA team, but this should be minimised. Independence should be preserved and be seen to be preserved as a priority.

Internal Audit coverage

What audits, reviews, advice, and support IA actually provide will be significantly influenced by the status and context of the council. The audit planning process will have determined that

Of increasing significance to authorities is their resilience, financially and organisationally. There is a legitimate role for IA to provide assurances regarding resilience, in how the MTFS has been created and managed, the robustness of the annual budgets, how savings and efficiencies are being delivered, the success of major transformational change programmes and the delivery of major projects. These of course will vary significantly between authorities, but it is increasingly important that IA is contributing to the achievement and success of the most corporately significant matters.

The relationship between IA and the S151 Officer is of particular importance. The audit of the core financial systems will appear in the audit plan every year in some form. This work aims to provide significant assurance to the S151 Officer and wider senior management team of the integrity and robustness of the control framework of the systems that handle large numbers of transactions and account for all the authority’s income and expenditure. Audit coverage of the core financial systems may well be established and captured in a specific audit strategy / approach. Such a strategy would also be discussed with the council’s external auditors.

The core financial systems typically cover:

- accounts payable / purchase to pay

- accounts receivable / income

- payroll (employee admin / organisational management)

- main accounting / budget management

- housing rents

- council tax

- Non-Domestic Rates

- housing benefits

- Treasury management

- fixed assets

- insurance.

Looking at the various Best Value and Peer Challenge reports or the Reports in the Public Interest issued by external auditors, there is a common theme of a general lack of effective ‘scrutiny’ and challenge. Whilst there are many opportunities for this to happen through normal management and executive arrangements, the reports raise a question regarding how IA was used. A highly effective IA cannot of course guarantee that major failings will be avoided, but it should make a significant impact in minimising the risk. This is of course predicated on the culture of the authority enabling IA and importantly listening to it.

Alongside the key areas of strategic activity, IA will undertake a range of other audits, reviews and provide advice or consultancy support. The HoIA will ensure there is adequate provision for the management of the IA function itself, the actual planning process, reporting and liaising with management, attending, and reporting to the audit committee, undertaking quality assurance work, and maintaining the Quality Assurance and Improvement Programme (QAIP) as required by the PSIAS.

The IA plan is also likely to contain reviews or independent input to major project boards and partnership arrangements. The governance of major projects, contracts, partnerships, collaborations, or joint ventures feature regularly in critical external reports where costs may have gone out of control, governance over decision-making is weak or there is a critical delay in implementation that then undermines any benefits that were expected. This is another key space for IA. It is a good practice to have an experienced senior member of the IA Team, if not the HoIA, to be part of any major initiative of the authority. Having such a role should not fetter the independence of the auditor but it should be clear from the outset what role they are performing. Having this formally captured in the relevant terms of reference is key, such that roles and responsibilities are not blurred, and true independent and objective advice, support and challenge can be given.

The integrity of IT systems is an increasing risk. The HoIA should have regular discussions with the Head of IT to keep abreast of changes in the IT infrastructure, such as moving systems to the cloud, new IT system procurements and enhancements, and the cyber resilience of the authority Alongside the Head of IT, the HoIA should also have regular discussions with the council’s statutory Data Protection Officer. Their roles are in many ways similar, and any mutual assurance from their respective activities should be shared.

A growing area where IA may be able to give assurance is around the authority’s sustainability and environmental responsibilities and commitments, another area likely to feature on a strategic risk register. It is also probably only a matter of time before the public sector will be required to report on their ‘ESG’ (Environment, Social and Governance) responsibilities.

Furthermore, the way we all work has changed since the pandemic and has presented the need for councils to review and change policies, procedures, guidance, systems, and controls. It has certainly changed the processes of supervision and management. IA should be aware of those changes, indeed be consulted on them, and give assurance on their effectiveness and how they are being complied with.

In general terms, there is increased pressure on councils to take managed risks. IA can assist in advising where the risks are if policies are changed, for example allowing greater officer or member delegations and/or raising various thresholds. It is management’s responsibility to manage those risks.

There are also likely to be a myriad of smaller audits to deliver that ‘diagonal slice’ and for IA to have a periodic ‘presence’. For example, periodic audits will take place in remote sites like museums or other cultural sites where there may still be significant cash taken, valuable assets managed and where the public attend introducing issues such as health and safety.

A good checklist for where IA coverage should be targeted would be the list of corporate objectives, key strategies, and major policy areas. Whether through a specific audit or providing advice through involvement in a ‘board’ or ‘steering group,’ there is likely to be great value that IA can provide

Below is an example of an audit assurance approach to consider the broader perspective of a strategy:

- What is the ‘problem’ the strategy is seeking to address? What’s driving it?

- Is it articulated in a clear way and understood by appropriate staff/stakeholders – so there is a clear buy-in to it and how is it woven / linked into other working practices, policies, procedures, reporting.

- How is it being communicated, so everyone understands their duties, roles and responsibilities and contribution?

- What are the core ‘ingredients’ to make it successful - money, people, systems, data, contracts / 3rd parties, performance management, risk management, decision-making, governance, reporting, escalating, dependencies (e.g. on other strategies?), any fraud vulnerabilities?

- How is progress / delivery being monitored and reported? Are action plans effective and driving progress and accountability? How are Business Units being held to account for their input to the strategy?

- Is there a ‘board’ that oversees the strategy? How does this work? Is the strategy formally reviewed?

- What are the critical success factors / KPIs that will say ‘job done’? How will delivery / success be sustained longer-term?

- What will drive the next strategy?

Given the focus of IA work should be risk based, an area that requires independent assurance is the corporate risk management approach itself. If IA can rely on the effectiveness of the actual risk management process, then this will support the creation of an effective and appropriate IA plan.

One activity that ideally IA should not be involved in however is writing the Annual Governance Statement (AGS) which is a job for management. A more appropriate use of IA is to undertake an independent assessment of how the review of governance effectiveness has been undertaken, what issues and improvements have been identified and that effective actions have been identified and delivered.

Like all plans, the IA plan is prepared at a point in time and will change due to changed corporate priorities, staffing issues, urgent requests and planned jobs taking longer than anticipated. The IA plan needs to be constantly reviewed and adjusted. It is also common practice for the IA plan to contain a contingency of unallocated days to accommodate plan pressures without unduly impacting on the planned work. The level of contingency is normally between 5-10 per cent.

Any significant plan changes should be shared and discussed with senior management and the audit committee to give assurance that sufficient work will be completed to enable the HoIA to provide that annual opinion and report. Any material resource issues should be discussed as a matter of urgency with the S151 Officer.

Ultimately, the HoIA should be able to demonstrate the delivery of the plan and present the annual report to management and the audit committee that highlights the following:

- How coverage has aligned to the strategic risks, concerns, and issues of the Authority.

- The contribution to assurance in respect of the Authority’s governance framework and in support of the Annual Governance Statement.

- Coverage of the core financial systems in support of the S151 Officer and validation of grant claims (for example, government funded).

- Support to any major transformation programmes.

- Assurance on any changes to working styles and practices to ensure compliance and maintenance of effective controls.

- Assurance regarding the council’s partnership governance arrangements and environmental programme and commitments.

- Project governance and overall project and performance management including management of assets;

- Key areas of advice given, particularly in specialist areas like procurement, contracts, IT and project/programme management.

- Assurance work in respect of information governance, information management and support the council’s Data Protection Officer and the results of any specifically commissioned reviews.

The HoIA will have calculated the core ‘capacity’ of the IA Team in determining a total of ‘productive days,’ taking account of leave, provisions for training, sickness absence, corporate activities, recruitment, performance management, management / team meetings etc. The HoIA therefore has a number of days to deliver the IA plan.

The IA plan may contain those days allocated to specific pieces of work. This is always indicative, a guide for the HoIA to have a general sense of what is going to be achievable over the course of the plan period. It is the responsibility of the HoIA to deliver appropriate and sufficient assurances through pieces of audit work such that professional standards are met, and the authority receives an evidence based and well-rounded assurance opinion. It is of course the responsibility of the HoIA to demonstrate that they have delivered the plan in as an efficient and effective way possible.

Audit reporting and opinions

Most pieces of audit work follow a fairly standard process. This will vary to some degree depending on the complexity of the area being reviewed but most will have these stages:

| Terms of reference | A more detailed scoping document is prepared in advance, in consultation with the audit sponsor and other key contacts. This will cover the context for the review, scope, links to risks, objectives (the extent to which the work covers controls, risks, and governance), the methodology to be used, timescales, key client contacts, the audit staff assigned to the work, and who will receive the draft and final reports. |

| Information gathering, assessment and analytical review |

Almost all audits will require the collection, consideration and analysis of data, reports, policies, guidance, transactions etc. before the fieldwork stage. Such data / information is then used to help the auditor identify key areas to focus on, any samples to test, who to speak to and the general approach needed. |

| Fieldwork |

This stage incorporates the discussions, transactional testing, and general review work, on-site, although this is increasingly virtually. The auditor will assess the relevant control, risk, or governance arrangements in terms of their existence and effectiveness. Findings and their implications are then determined. |

| Draft report |

Captures the key messages, findings, and implications. Such reports will vary in length and style of course (and designed in consultation with management), but the primary aim is to prepare a draft for discussion with key client contacts and/or the sponsor for factual accuracy and to obtain management’s response, capturing what action they are going to take. The overall assurance opinion will also be discussed. |

| Final report |

Includes management responses / actions and reflects any discussions between the auditor and client. This version is usually then distributed to a wider audience, subject to any agreed protocols. |

| Feedback |

It is good practice for the HoIA to request feedback, usually through a standard questionnaire on various aspects of the audit assignment. Such a questionnaire should highlight where the audit could have gone better, but importantly the value it has given to the sponsor. |

In most cases each piece of assurance work will produce an individual opinion. These individual opinions will aggregate to help the HoIA determine their overall annual opinion alongside the extent to which management have heeded any advice provided promptly and effectively implemented actions and any assurances obtained from other sources, like inspectors, regulators, or external audit.

There is a general consistency across IA providers of having a range of levels of assurance. Typically, these are four, two regarded as ‘positive’ assurance, and two as ‘negative’ assurance These are described positively as ‘substantial’ or reasonable’, and negatively as ‘limited’ or ‘none’. Other descriptions may be used such as ‘high or full’, ‘satisfactory’, ‘partial’, or ‘unsatisfactory’.

Traditionally, IA make recommendations to management. These are based on the findings from the audit and IA’s judgement of what is required to address a control, risk or governance improvement that has been identified. There is a growing trend of IA identifying the implications of their findings that then prompt management to determine the action. This is perhaps a better way to ensure management take responsibility to address the issues identified. As such, rather than audit recommendations, it is agreed management actions that are included in the final audit report.

In either case, Internal Audit will follow up reports to ensure that management action has been taken and will report to audit committee the outcomes of these follow-ups.

The overall opinion arising from the piece of work is based upon the significance of the findings / implications. This is the professional judgement of the HoIA rather than applying any kind of ‘formula’ based on the number or significance of the issues raised. Most IAs will have some general guidance regarding how the assurance opinion is determined.

The following serves as a general guide to the basis of these opinions:

- Substantial Assurance - “A sound system of governance, risk management and control exist, with internal controls operating effectively and being consistently applied to support the achievement of objectives in the area audited.”

- Reasonable Assurance - “There is a generally sound system of governance, risk management and control in place. Some issues, non-compliance or scope for improvement were identified which may put at risk the achievement of objectives in the area audited.”

- Limited Assurance - “Significant gaps, weaknesses or non-compliance were identified. Improvement is required to the system of governance, risk management and control to effectively manage risks to the achievement of objectives in the area audited.”

- No Assurance - “Immediate action is required to address fundamental gaps, weaknesses or non-compliance identified. The system of governance, risk management and control is inadequate to effectively manage risks to the achievement of objectives in the area audited.”

A further nuance to how findings / implications or indeed recommendations are classified is to distinguish between ‘control adequacy (or control existence)’ and ‘control application (or compliance)’. This classification is often a helpful indication of where management attention is needed – to improve the basic framework of controls (risk management or governance) or to improve compliance, or both of course.

The HoIA may well draw out such classifications in their annual report to present a wider picture of the effectiveness of the council’s control, risk, and governance arrangements.

These individual reports and the HoIA’s annual report should be of interest to the senior management team to assist in the continual improvement of the controls, risk management and governance of the council to support the achievement of its objectives and demonstrate its public accountability.

Internal Audit impact and performance

Given the role and responsibilities of an IA function, having assurance in the quality of IA itself is fundamental to it being deployed, used, and supported to perform and deliver its important role.

The simplest measure of IA effectiveness is through feedback from the senior management ‘sponsors’ of the audit work. A HoIA may have a range of more operational performance measures to keep a track on the delivery of the plan, how staff are utilised for example, but there remains no better measure than the satisfaction of an audit sponsor regarding the usefulness and value of a piece of work.

To a chief executive, member of the senior management team or indeed the audit committee, the impact and influence of IA is of great significance. There must be a real sense of benefit, improvement and insight generated from IA work beyond the comforting assurance that the basics are working well, as important as that is.

The external quality assessment (the EQA) required under the PSIAS should have a focus on that impact and influence measuring IA against the principles set out in the standards providing further and independent assurance of IA’s effectiveness.

It is not necessary for a chief executive or members of the senior management team to have a detailed understanding of the Public Sector Internal Audit Standards but they should know in general what is necessary to ensure compliance (see Annex one). The audit committee should have such an understanding of their role of holding the HoIA to account.

Annex six provides a typical calendar of the IA cycle and associated activities.

Internal Audit, the audit committee and members

The HoIA will report into a member arena, usually an audit committee, but usually only by exception to a cabinet or other executive member body formally. That is not to say that the leader/ mayor/ chair of the policy and resources committee, or any other member should not be able to contact and liaise with the HoIA.

Annex three provides information about the role of the audit committee in relation to internal and external audit. This guide does not cover the effectiveness of the audit committee as such. Suffice to say however, that the effectiveness of an audit committee and therefore its relationship with both sets of auditors is significantly influenced by the organisational culture.

External audit (sometimes referred to as local audit)

At the time of writing the local audit system in England is facing considerable challenges. This ‘Must Know’ guide describes the system as it would normally work.

The external auditors are the regulated and independent professional firm appointed with a statutory mandate to audit the council. They are responsible to ‘those charged with governance’ who, in a council setting, are its elected members, normally represented by an audit committee.

In basic terms, the external auditors provide assurance to residents and the council that the council’s finances are soundly managed, and the annual accounts present a true and fair view of the council’s income and expenditure and its assets and liabilities.

The importance of local audit

A robust local audit system and transparent local authority financial reporting are key to delivering value for money for taxpayers, and for sustaining public confidence in our systems of local democracy. The statutory accounts are the only information provided by local authorities that are independently verified through external audit. For users of the accounts to trust and rely on this information, they must both have confidence that the audit process is robust and be able to understand what the financial reports are telling them. A separate Must Know guide covering the financial statements is available.

The external auditor of a local authority is also required to provide an annual commentary on the authority’s arrangements for achieving value for money under three reporting criteria; financial sustainability, governance and arrangements to improve economy, efficiency and effectiveness.

External auditors have a duty to inform stakeholders of matters of importance. The issues covered within public interest reports (PIRs) issued in relation to a number of authorities over the last few years demonstrate the crucial role of external audit in bringing concerns into the public domain. It is equally important that robust governance mechanisms are in place within local authorities to review and, if necessary, act on audit findings.

Audit ensures transparency and accountability and, when done well, encourages authorities to have strong governance and financial records. It also encourages organisations to follow the relevant financial and regulatory frameworks.

Effective, high-quality audit is becoming increasingly important as local authorities’ accounting practices become more complex and the sector comes under financial pressure. For example, in recent years more councils have been borrowing to fund schemes to generate commercial income. This has changed the risks that councils are facing, so it is essential that the financial reporting and audit process is able to make these risks clear and that are being well managed.

Finally, external audit is a key assurance mechanism. A local authority’s audited accounts allow the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities, in its role as the steward of the local government accountability framework, to be assured that the authority has been acting with regularity, propriety and value for money in the use of their resources.

The legal basis and arrangements and responsibilities for the delivery of local audit

The legal basis of external audit is provided via the Local Audit and Accountability Act 2014. The next sections set out the various responsibilities of local authorities and local auditors. The context for how and indeed the limitations of working with (external) auditors is important to understand.

Responsibilities in relation to the financial statements

The financial statements of local government are an essential means by which a local authority accounts for the stewardship of the resources at its disposal and its financial performance in the use of those resources. The authority is responsible for preparing financial statements that meet relevant statutory, professional and any other applicable requirements.

In carrying out their responsibilities in relation to the financial statements local auditors comply with auditing standards, where applicable, as well as other relevant guidance.

Auditors provide an opinion on whether the local authority’s financial statements:

- give a true and fair view of the financial position of the authority and its expenditure and income for the period in question

- have been prepared properly in accordance with the relevant accounting and reporting framework as set out in legislation, applicable accounting standards or other direction.

Auditors plan and perform their audit in compliance with the requirements of the Audit Code of Practice and with relevant professional and quality control standards. The auditor’s work is risk-based and proportionate and is designed to meet the auditor’s statutory responsibilities, applying the auditor’s professional judgement to tailor their work to the circumstances in place at the authority and the audit risks to which they give rise.

Auditors examine selected transactions and balances on a test basis and assess the significant estimates and judgements made by the authority in preparing the annual accounts. In conducting their work, the auditors exercise professional scepticism. They obtain and document such information and explanations as they consider necessary to provide sufficient, appropriate evidence in support of their judgements.

Auditors evaluate significant financial systems, and the associated internal financial controls, for the purpose of giving their opinion on the annual accounts. However, they do not provide assurance to an authority on the operational effectiveness of specific systems and controls or their wider system of internal control; this is internal audit’s role. Where auditors identify any weaknesses in such systems and controls, they draw them to the attention of the authority, but they cannot be expected to identify all weaknesses that may exist.

Auditors review whether the Annual Governance Statement has been presented in accordance with relevant requirements and reports if it does not meet these requirements or if it is misleading or inconsistent with other information of which the auditor is aware. In doing so, auditors take account of the knowledge of the authority gained through their work in relation to the annual accounts and through their work in relation to the authority’s arrangements for securing economy, efficiency, and effectiveness in the use of its resources.

Auditors are not required to consider whether the Annual Governance Statement covers all risks and controls, nor are auditors required to express a formal opinion on the effectiveness of the audited body’s corporate governance procedures or risk and control procedures, although they may comment on all of these things as part of their work.

Auditors are also mindful of the activities of inspectorates and other bodies and take account of them where relevant to prevent duplication and ensure that the demands on the authority are managed effectively. In so doing, the auditor is not required to re-perform the work of inspectorates and other bodies, except where it would be unreasonable not to do so.

Auditors review for consistency other information that is published by the authority alongside financial statements, such as an annual report. If auditors have concerns about the consistency of any such information, they will report them to the audit committee.

Additional powers and duties of auditors

Auditors have additional powers and duties under the Local Audit and Accountability Act 2014 in relation to matters of legality. Auditors undertake the following in relation to these duties.

| Consideration of additional powers and duties |

|

It should be stressed that taking such action would never occur without significant discussion with the S151 officer, chief executive, monitoring officer, and indeed the head of internal audit. Having effective arrangements in place for regular liaison with the authority’s auditors is therefore essential.

Reporting the results of audit work

Auditors provide the following for local authorities:

- Audit planning documents.

- Oral and/or written reports or memoranda to officers and, where appropriate, directors on the results of, or matters arising from, specific aspects of work.

- A report to those charged with governance, normally submitted to the audit committee, summarising the work of the auditor; an audit report, including the auditor’s opinion on the financial statements and reporting by exception on whether the authority has put in place proper arrangements for securing economy, efficiency, and effectiveness in its use of resources.

- A certificate that the audit of the accounts has been completed in accordance with statutory requirements.

- An auditor’s annual report addressed to the authority, which is based on the report to those charged with governance. A key element to this report is the commentary on VFM arrangements.

Audit reports are addressed to officers of the authority as appropriate. Auditors do not have responsibilities to officers or directors in their individual capacities or to third parties that choose to place reliance upon the reports from auditors.

Outputs arising from the exercise of additional powers and duties of an auditor, the need for which may arise at any point during the audit process, are issued when appropriate.

Matters raised by auditors are drawn from those that come to their attention during the audit. The audit cannot be relied upon to detect all errors, weaknesses, or opportunities for improvements in management arrangements that might exist. Authorities should assess auditors’ recommendations for their wider implications before deciding how to implement them.

Ad hoc requests for auditors’ views

There may be occasions when the chief executive, S151 officer, or monitoring officer particularly, seek the views of auditors on the legality, accounting treatment or value for money of a transaction before embarking upon it. In such cases, auditors are as helpful as possible, but are precluded from giving a definite view because auditors:

- must not prejudice their independence by being involved in the decision-making processes of the authority

- are not financial or legal advisers to the authority

- may not act in any way that might fetter their ability to exercise the special powers conferred upon them by statute.

In response to such requests, auditors can offer only an indication as to whether anything in the information available to them at the time of forming a view could cause them to consider exercising the specific powers conferred upon them by statute. Any response from auditors should not be taken as suggesting that the proposed transaction or course of action will be exempt from challenge in future, whether by auditors or others entitled to raise objection to it. It is the responsibility of the authority to decide whether to embark on any action or transaction.

The appointment of external auditors

Councils are responsible for appointing their own auditors but nearly all of them opt into to a national scheme for this purpose.

The national scheme is run by Public Sector Audit Appointments Limited (PSAA), which was incorporated by the Local Government Association (LGA) in August 2014.

In July 2016, the Secretary of State for Housing Communities and Local Government specified PSAA as an appointing person for principal local government and police bodies for audits from 2018/19, under the provisions of the Local Audit and Accountability Act 2014 and the Local Audit (Appointing Person) Regulations 2015. The appointment was renewed for the following procurement covering audits from 2023/24 onwards.

Acting in accordance with this role PSAA is responsible for appointing an auditor for every opted-in authority and setting scales of fees for audits.

The appointment of the auditor is a decision of full council. This includes the decision to opt into the national scheme.

Working with External Audit

The functions of external audit (EA) are determined through the National Audit Office’s Code of Audit Practice and whilst there are opportunities to ask for views from the external auditor, their core work is pre-ordained. The external auditor is required however to set out their plan of work that will take cognisance of the nature and context of the authority.

An important part of the external audit planning process is through liaison and discussion with the chief executive, S151 Officer, Monitoring Officer and HoIA. Regular contact should enable the external auditor to maintain a good understanding of the authority’s key issues, challenges, and developments, that will help to inform where any audit focus will be needed.

The external auditor will be particularly interested where an authority is planning to embark on a major commercial enterprise, a significant capital programme, a major out- or in-sourcing project, any major system implementation, or any joint ventures. As well as their core work on the audit of the financial statements, there is the work on VFM looking at the three areas:

- financial sustainability – how the authority plans and manages its resources to ensure it can continue to deliver its services

- governance – how the authority ensures that it makes informed decisions and properly manages its risks

- improving value for money – how the authority uses information about its costs and performance to improve the way it manages and delivers its services.

EAs work is focussed on the financial year with their work being largely undertaken after the year has ended. For example, the work needed to provide an opinion on the financial statements of a particular financial year and then prepare the VFM narrative will be typically undertaken between the June and December following the financial year-end.

The results of EA’s planning work will result in an audit plan. This will typically cover the following ‘key matters’:

- the national context and any influences that context has on the local audit

- the local context, looking at the council’s financial performance, its MTFS, any financial pressures (such as, SEND, CSC, ASC etc.), major projects.

The plan will highlight specific and significant risks which are focussed on the risk of the likelihood of material financial misstatement. These cover:

- management over-ride of controls

- valuation of land and buildings

- valuation of the net pension fund balance.

Given the significance of IT systems in the preparation of the financial statements, EA will also have their own IT audit strategy to examine the key technical and environmental controls. One of the ISAs requires EA to obtain an understanding of the relevant IT and technical infrastructure and the details of processes that operate within the IT environment. In most councils (subject to the type of authority), EA will focus on the core financial systems, incorporating financial reporting and payroll, council tax, business rates, housing benefits and housing rents.

The cycle / calendar of audit activity and reporting will also be included in the audit plan. This is significantly determined by the statutory deadlines for the approval of the financial statements. These have changed in recent years to accommodate the impact of the pandemic and difficulties in the EA market where many of the audit firms are having considerable difficulty in meeting the statutory dates. This is the subject of significant national discussion. However, the problems of resourcing EA are ultimately solved, there will be a calendar of EA activity linked and scheduled to audit committee reporting and the issue of the report on the financial statements, the audit findings report and the Auditor’s Annual Report on VFM arrangements.

The plan document will also highlight the fees for the audit. These comprise various elements, typically fees covering:

- the scale fees determined through a national formula

- the increased challenge and depth of audit work to meet the requirements of the regulator

- the enhanced audit procedures around plant, property, and equipment (PPE)

- the revised VFM work required

- enhanced technical audit procedures

- any local circumstances that require additional audit assurance work.

An important part of the plan document is EA’s statement on their independence, to explain their obligations to disclose all material facts and matters that may bear upon the integrity, objectivity and independence of the audit firm or persons involved in the audit and the extent and nature of other services that they may provide. Such other services are likely to be around grant certifications and returns (housing benefit grant, teachers’ pensions return and pooling of capital receipts, subject to the type of authority).

It would be the norm for the key external audit partner & engagement lead to present the audit plan in person to the audit committee having discussed and shared a draft with the chief executive, S151 officer, monitoring officer and HoIA.

Given the significant prescription around the roles and responsibilities of EA, there is limited scope to change what they will audit. That said, it is important to foster a good and open relationship with EA to help make their audit work as efficient and effective as possible and therefore provide the authority with a quality audit.

Internal and External Audit Liaison

It is important that there are arrangements in place to ensure effective liaison between the two sets of auditors. It is a given that in the event of anything exceptional or urgent that one would contact the other, but a quarterly discussion would be appropriate.

Although there are significant synergies between the areas of focus for both auditors, as has been described, their remits are quite separate. External Audit do not ‘rely’ on the work of IA and indeed are not allowed to under the Code of Audit Practice. They have an interest in what IA may report upon and it is accepted good practice that EA have access to all IA reports. The regular liaison would also serve to keep EA informed of any important control or governance issues that IA were finding.

Although less likely under the current Code of Audit Practice, it is still important to ensure that IA and EA work does not unduly overlap or duplicate. The sharing of plans and the results of work provide mutual assurance.

EA may follow-up on matters identified by IA and certainly get assurances that any high priority management actions (recommendations) have been implemented, or there are clear plans in place.

For more information about ‘working with auditors’ and how to get the best from that relationship, speak to them.

Annex 1 - Public Sector Internal Audit Standards (PSIAS)

Whilst a chief executive would not normally need to have a detailed knowledge of the PSIAS, being aware of what they cover and how the HoIA is held to account for conforming with them is important to provide assurance that you are receiving a high-quality IA service.

The PSIAS contain a Code of Ethics for internal auditors. It is perhaps obvious given the role and responsibilities of IA, but the Code of Ethics cover:

Integrity – ensuring internal auditors perform their work with honesty, diligence, and responsibility, observe the law, and make any disclosures required by law.

Objectivity – ensuring that internal auditors exhibit the highest level of professional objectivity in undertaking their work and always make balanced assessments avoiding any influence from their own interests or from others.

Confidentiality – ensuring that internal auditors respect the value and ownership of the information they receive and do not disclose any information without appropriate authority unless there is a legal or professional obligation to do so.

Competency – ensuring internal auditors apply the knowledge, skills and experience needed to perform IA services.

Through the PSIAS, the HoIA is accountable for ensuring all IA staff understand and comply with the Code of Ethics.

The PSIAS themselves contain four Attribute standards and seven Performance Standards. Again, it is not essential that the CX has a detailed knowledge of what these Standards contain, but having an appreciation is valuable to give confidence of the quality of IA provision.

The Attribute Standards cover:

- the purpose, authority, and responsibility of IA

- independence and objectivity

- proficiency and due professional care

- quality assurance and improvement programme. *

The Performance Standards cover:

- managing the IA activity

- nature of IA work

- engagement planning

- performance of the engagement

- communicating results

- monitoring progress communicating the acceptance of risks.

* Within this element of the PSIAS is the requirement for the HoIA to maintain a Quality Assurance and Improvement Programme (QAIP) and for the function to be subject to an independent external quality assurance review.

Of all the elements of the PSIAS, the Core Principles for the professional practice of internal auditing provide a clear set of objectives for the HoIA to demonstrate and be held accountable for.

These principles are that IA:

- demonstrates integrity

- demonstrates competence and due professional care

- is objective and free from undue influence (independent)

- aligns with the strategies, objectives, and risk of the organisation

- is appropriately positioned and adequately resourced

- demonstrates quality and continuous improvement

- communicates effectively

- provides risk-based assurance

- is insightful, proactive, and future-focussed

- promotes organisational improvement.

Of particular relevance to a chief executive and indeed the senior management of the organisation are the last two above. Working with IA and getting the greatest organisational value and assurance are key.

Professionally, in their guidance on the role of the S151 officer, CIPFA place a responsibility with that officer to ensure the IA function is adequately resourced and effective.

Annex 2 - Internal Audit Delivery Models

Internal auditing standards apply to any internal audit service, regardless of the model employed, but do not mandate the model that should be used. There are several different models of internal audit service.

In-house – the internal audit service is provided by a team of people who are employees of the organisation.

Outsourced – the internal audit service is provided by a team of people who are not employees of the organisation. This may be through a shared service, a formal commercial contract, or another partnership arrangement.

Co-sourced – an in-house internal audit service that secures some of its resource from external parties. This may be on an ad hoc basis or a formal partnering contractor arrangement. This is often a model used by in-house teams to procure particular expertise or skills to augment the existing team.

All models can be effective, but the organisation must be mindful of what it needs to do to make its chosen model work. When selecting a model, the focus should be on what assurance is needed to facilitate informed prioritisation of coverage and the skills and quantum of assurance, not what assurance can be afforded in the allocated budget.

Organisations that have a good understanding of their assurance requirements and priorities will be better placed to make an informed decision about the nature of internal audit required and the best way to deliver that.

CIPFA has identified the following perceived advantages and disadvantages of the In-house and outsourced models of IA delivery as part of a major survey CIPFA undertook and published in May 2022 called Internal Audit: Untapped Potential

| In-house Internal Audit | |

|---|---|

| Advantages | Disadvantages |

| Better knowledge of the organisation and people within it. | Many internal audit teams are facing challenges in recruiting quality candidates with the skills required. |

| Easier to build effective working relationships with a constant presence. | The smaller the audit team, the more challenging it will be to have all the skills required within that team |

| An effective internal audit department can be used as a secondment to support management development programmes. | The risk of long-tenured team members may lead to impaired objectivity and innovation. |

| Regular liaison with other internal assurance functions and management. | Small internal audit teams in particular may find it difficult to provide succession and promotion opportunities. |

| Some heads of internal audit have a role in the management team and are therefore present for discussions on emerging issues and determining how internal audit can best support the organisation as priorities change. | Unplanned absences can delay the internal audit plan and impact service delivery. |

| If the internal audit budget allows for advice / consultancy, this can be provided as part of a budgeted cost rather than an additional fee. | |

| Outsourced Internal Audit | |

|---|---|

| Advantages | Disadvantages |

| Able to share good practice and lessons learned observed in other organisations. | Lack of clarity over responsibility and accountability for internal audit and assurance. |

| Able to provide benchmarking or comparative data from similar organisations. | There may be reluctance to provide formal assurance opinions on certain topics. |

| More options and flexibility to provide staff or subject matter expertise. | The risk that management will not perceive their responsibility for maintaining an effective internal audit function. |

| A shared service model could allow for staff to be based predominantly with one client and therefore to build knowledge of the organisation. | The organisation may not engage as effectively with an external provider. |

| Lack of organisational knowledge, including of the culture of the organisation. | |

| A contract manager or key contact is still required to ensure effective liaison between the organisation and the internal audit provider. | |

| The risk of high staff rotation leading to lack of familiarity with the organisation. | |

| A focus on price rather than quality when contracting for an outsourced service may prohibit extensive input from senior staff or specialists. | |

Annex 3 - The Audit Committee and the Auditors

There is an important relationship with all authorities between the internal and external auditors and the audit committee. The status and profile of the audit committee can also be a reflection on the overall culture in an organisation. An effective and high-profile audit committee that is openly supported by the Chief Executive will support the role and work of both internal and external audit.

The following paragraphs draw on the 2022 CIPFA Guidance for audit committees in local authorities and provides a useful oversight of that relationship.

External audit

The independence of auditors is critical for confidence in the audit opinion and audit process. It is important for an audit committee to satisfy itself that the external auditor’s independence is safeguarded.

Each year, the external auditor will disclose to the committee an assessment of whether it is independent. The audit committee should use this opportunity to discuss with the external auditor their assessment of threats to independence and any safeguards.

Receiving and considering the work of external audit

The timetable of external audit work is shaped by the Code of Audit Practice and the appropriate regulations.

The audit committee should monitor changes to timetables and audit plans, supporting good communication between the auditor and the authority to manage difficulties in the best possible way.

It is considered best practice in some quarters for the external audit annual report to be submitted to full council, perhaps after detailed consideration by the audit committee. As all councillors are “charged with governance,” they should be aware of serious issues and the overall results of the audit.

Supporting the quality and effectiveness of the external audit process

The audit committee should support the quality and effectiveness of the external audit process.

The audit committee should be briefed on any relevant issues around quality that emerge from the regulation of external audit.

There should be an opportunity for the audit committee to meet privately and separately with the external auditor, independent of the presence of those officers with whom the auditor must retain a working relationship.

Supporting audit quality

The audit committee should be an advocate for high audit quality.

The committee should ask about the auditor’s approach to audit quality, including the support and training provided to the team on specialist areas within the scope of the audit.

The audit committee needs to work with auditors and key officers to ensure that there is a shared understanding of objectives, expectations, and outcomes from the audit.

Where there are difficulties in the relationship between auditor and client, the audit committee should seek to support and resolve in an objective way that helps the delivery of a quality and timely audit.

Internal audit

The audit committee has a clear role in relation to oversight of the authority’s internal audit function.

Each authority should consider which committee or individual is the most appropriate to fulfil the role of the council in relation to internal audit. An audit committee will usually fulfil the role of the council.

The role of the audit committee in relation to internal audit is to:

- oversee its independence, objectivity, performance, and professionalism

- support the effectiveness of the internal audit process

- promote the effective use of internal audit within the assurance framework.

The audit committee should consider internal audit’s quality assurance and improvement programme (QAIP) when conducting such a review.

For the head of internal audit to operate an effective internal audit arrangement, the audit committee should ensure that they can operate effectively and perform their core duties. This responsibility exists whether the service is provided in-house, outsourced or through a shared arrangement.

The committee should develop sufficient understanding of the effectiveness of internal audit and its adherence to professional standards and should also hold internal audit to account for the following:

- conformance with professional standards

- effective management of resources

- focus on risks and assurance needs

- delivery of required outputs

- impact.

Annex 4 - Typical layout / structure of an Internal Audit Plan

Whilst the management of the IA Plan is the responsibility of the HoIA, and likely to be managed within an audit management system, a document / spreadsheet is often prepared for use in meetings or presentation to the audit committee that typically contains key information.

The IA Plan should align with the strategies, objectives, and risks of the organisation. It can be useful for demonstrating that through such a document.

| Column | Purpose / Content |

|---|---|

| Directorate / Service | Simply to identify the area / sub-area of the authority the work relates to. This may also be ‘council-wide’ or ‘corporate’. |

| Assignment Title | A brief title given to the piece of IA work. |

| Outline Scope / Objectives | In the plan consultation process, there should have been sufficient discussion to enable a brief outline scope of the activity to be prepared. This will be confirmed and fine-tuned before the work is undertaken. That brief scope should highlight the key objectives of the piece of work. |

| Governance Domain / Area * | This is good practice to link which aspect of the authority’s governance framework the IA activity is going to cover and therefore provide assurance on. This is important for the HoIA to demonstrate coverage of ‘governance’ as part of the overall annual opinion. |

| Risk Register Link | As IA work is risk-based, there should be a link, where relevant, to the strategic / corporate / operational / project risk contained in the risk registers. This is a fundamental aspect of IA planning. |

| Objective / Strategy / Policy Link | IA work is likely and should consider and contribute to the successful delivery of strategies and policies. It is important that IA cover the ‘big-ticket’ strategic matters to provide the greatest value and assurance. |

| SMT Sponsor | Each piece of work should have a sponsor, and to get senior management buy-in, it is useful to have the relevant SMT member named as the key senior contact and client for the piece of assurance work. |

| Priority | As the list of potential areas for IA to undertake is going to exceed their capacity, a simple ‘H / M / L’ priority can be useful to include in the plan document. |

| Indicative Days | This is predominantly for the HoIA to be able to understand how fare their IA resources will go in the delivery of high and medium priority work. |

| Control / Risk / Governance | Identifying which of control / risk / governance is the primary focus for a piece of work is useful for the HoIA to assess the coverage across the three elements to support the three separate annal opinions. Most pieces of assurance work will include a combination of C/R/G. |

| Quarter to start | In consultation with the sponsor, it is useful to have at least an indicative quarter that the work will commence. This helps the HoIA spread the work across the year to be able to manage their IA resources. |

| Report or Advisory | Not all IA work will result in a formal report. Having the nature of the work identified is another useful view for the HoIA to assess the spread of work such that there is sufficient work to support the annual opinion. |

| Basis for inclusion | A brief sentence is useful to capture the initial discussion with management that determined that area’s inclusion in the plan. |

* Governance Domain / Area – a useful framework to use to define the policy framework of the authority through which all activity is undertaken. Every aspect of what an authority delivers is facilitated through a combination of these governance domains. Below is one version to separate the various elements of a governance framework, but the terminology would vary according to what made sense in a particular authority. These domains can also be used to link IA recommendations or risk mitigation actions such that there is a common language created that promotes a better understanding or corporate responsibilities and accountability.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Annex 5 - The Three Lines Model

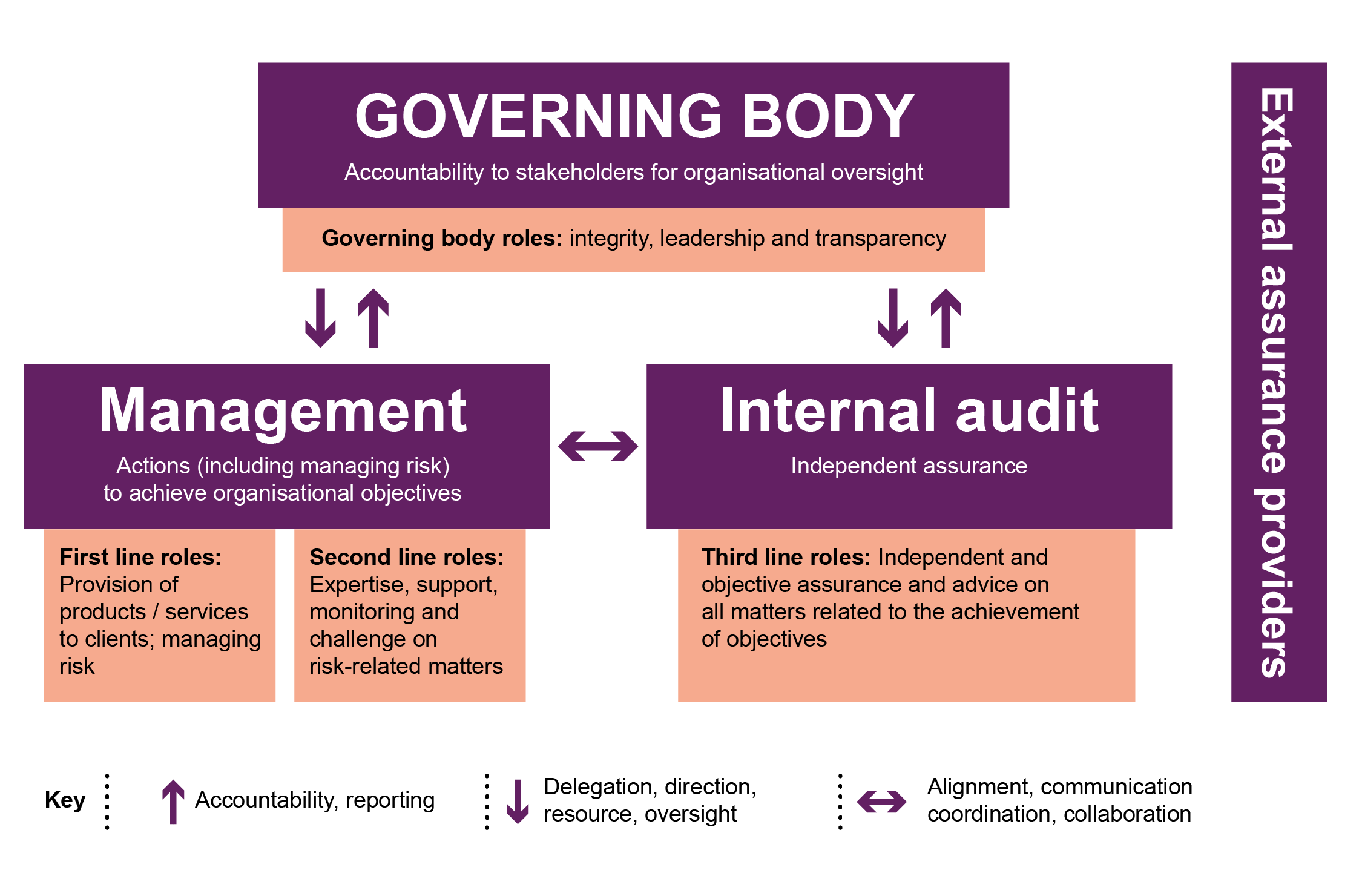

A model has evolved over the years that sets out organisational responsibility and accountability – the Three Lines Model, alternatively known as the Three Lines of Defence. In simple terms it provides a useful ‘visual’ to set out the ‘lines’ of responsibility and accountability, and where IA and EA fit in.

Copyright © 2020 by the Institute of Internal Auditors Inc. All rights reserved

Although perhaps somewhat obvious, it is worth setting out what is meant by the roles and responsibilities of the Governing Body and the first and second line roles of Management that could be used as a high-level focus for the organisation in setting expectations.

The governing body (Full Council normally represented by an audit committee)

- Accepts accountability to stakeholders for oversight of the organisation.

- Engages with stakeholders to monitor their interests and communicate transparently on the achievement of objectives.

- Nurtures a culture promoting ethical behaviour and accountability.

- Establishes structures and processes for governance, including relevant committees as required.

- Delegates responsibility and provides resources to management for achieving the objectives of the organisation.

- Determines the organisational appetite for risk and exercises oversight of risk management (including internal control).

- Maintains oversight of compliance with legal, regulatory, and ethical expectations.

- Establishes and oversees an independent, objective, and competent internal audit function.

Management

First line roles (Senior management)

- Leads and directs actions (including managing risk) and the application of resources to achieve the objectives of the organisation.

- Maintains a continuous dialogue with the governing body, and reports on planned, actual, and expected outcomes linked to the objectives of the organisation; and risk.

- Establishes and maintains appropriate structures and processes for the management of operations and risk (including internal control).

- Ensures compliance with legal, regulatory, and ethical expectations.

Second line roles (Compliance management)

- Provides complementary expertise, support, monitoring, and challenge related to the management of risk, including:

- The development, implementation, and continuous improvement of risk management practices (including internal control) at a process, systems, and entity level.

- The achievement of risk management objectives, such as: compliance with laws, regulations, and acceptable ethical behaviour; internal control; information and technology, security; sustainability; and quality assurance.

- Provides analysis and reports on the adequacy and effectiveness of risk management (including internal control).

Of critical importance and is demonstrated in this model that should be replicated in how the organisation is structured and responsibilities are made clear, is that the third line, IA (and EA), is not a replacement for management’s responsibilities and accountability.

Annex 6 - Typical Internal Audit cycle / calendar

This will be significantly similar in all local authorities given the legislative requirements for the annual financial statement and the annual governance statement. It will potentially vary a little according to any changes in those statutory timescales.

The activity below ‘starts’ with the audit planning process.

|

Qu. |

Month |

Internal Audit Activity |

Linkages and inputs |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

4 |

Jan. |

Monthly liaison meetings with senior management.

Specific 1:1s with the CX, S151 and MO – if not monthly then quarterly.

Monitoring the delivery of the IA plan to look where changes are needed and discussed with the relevant senior officer.

HoIA meetings with the Chair of the Audit Committee – again, if not monthly then quarterly.

|

IA planning – research within the IA team, consultation with management and the audit committee, culminating in the IA plan being presented to SMT and then the audit committee usually before 31st March. | Quarterly IA report to audit committee | SMT, Directorate management teams, specific officers e.g., Head of HR, Head of IT, the Data Protection Officer, S151 Officer the Monitoring Officer, External Audit, and audit committee. |

| Feb. | |||||

| March | Update of the Audit Charter for presentation to the audit committee | ||||

|

1 |

April | Update report on the Quality Assurance and Improvement Programme (QAIP) | |||

| May | Drafting HoIA annual report and opinion | HoIA report may be draft at this stage to inform the draft AGS. | |||

| June | |||||

|

2 |

July | Quarterly IA report to audit committee | |||

| August | |||||

| Sept. | Confirming final HoIA annual report and opinion | HoIA opinion confirmed to be included in the final AGS | |||

|

3 |

Oct. | Quarterly IA report to audit committee | |||

| Nov. | |||||

| Dec. | |||||

|

4 |

Jan. | IA planning – research within the IA team, consultation with management and the audit committee, culminating in the IA plan being presented to SMT and then the audit committee usually before 31st March. | Quarterly IA report to audit committee | ||

| Feb. | |||||

| March | |||||