Newcastle City Council wanted to understand why certain families turn down the offer of early help, and to identify opportunities to increase the take-up of support.

The challenge

Each quarter, approximately 1,000 children and young people are recommended for early help in Newcastle. Once assessed and offered early help support, 20 per cent of those recommended for support decline the opportunity to participate.

The consequences of families declining the offer for early help are seen in a range of ways. For the children and families there can be significant negative impacts. Issues such as debt problems, addiction, behaviour challenges and mental ill health can become more complex and damaging to the individual, family and wider community.

Further, data reveals that where problems do continue to escalate in this way there is an increased financial impact for more extensive social care support delivered at a later stage. During the course of a year, the cost to the council is estimated at over £750,000 in delivering later stage support with statutory interventions for families.

The council hoped to understand more about what motivates people to accept or decline the early help offer and critically, what approaches can be used to influence families to accept the offer of support.

Our initial scoping work determined that the way in which early help is offered to and perceived by some families is inhibiting the take up of support. We also found that the use of child concern notifications (CCNs) as a blanket tool for police referrals results in inappropriate or inaccurate recommendations to offer early help support. However, the council was keen to focus the project on its own practice and services and so this was deemed to be unsuitable for our intervention.

The solution

Focusing on improving families’ perceptions of early help in order to improve take-up rates and decrease decline rates was determined as the ideal outcome. Using the evidence and insight gathered, a co-design session was held with the project team, to design our intervention and test it with a randomised control trial.

Understanding the challenge

To better understand our target audience, we performed a series of covariate analyses and chi-square tests to investigate variations in the decline rates of early help based on the following factors:

- contact source (where the recommendation for early help came from)

- seasonality (months and quarters)

- deprivation (based on the family’s location).

Our analysis revealed the following key findings:

- one in five families turn down the offer of early help

- one in four families of children whose safeguarding concern was raised by the police turn down the offer of early help

- one in three families of children living in less deprived areas whose safeguarding concern was raised by the police turn down the offer of early help.

We also found that the following challenges were being reported in interviews with families:

- social stigma is seen as a barrier to accessing early help

- awareness of the early help offer and what it consists of is low

- families often lack confidence in speaking openly about problems they are facing

- communication preferences of families being offered early help are not currently being met.

The intervention

The key components of our intervention, which was targeted at families that were offered early help, consisted of:

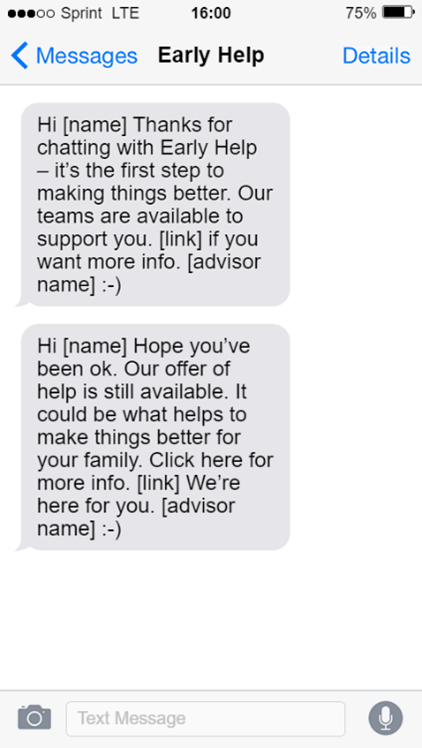

- two text messages (one sent immediately after an initial telephone call and the second sent 48 hours later)

- a redesigned early help information leaflet accessed via a link to the council’s website.

The intervention sought to encourage the families to accept the early help offer by:

- reassuring the parent of the benefits of accessing early help

- emphasising the positives of engaging

- providing another opportunity to engage

- using personalisation to build relationships

- making the offer clear, useful and practical.

Text number 1

This was sent on the same day as the initial call from the front door to the family.

The purpose of this was to reinforce the positive connection and to reassure the recipient of the benefit of accessing early help.

This text was sent to those that both accept and decline further support.

Text number 2

This was sent 48 hours after the initial text only to those who had declined the initial offer of support.

The purpose of this was to reassure the recipient support is still available and that it could be beneficial to their family.

The text aims to reinforce the positive connection with early help and to provide a link to online information about early help.

Early help information leaflet (online)

Parents who followed the link arrived at a webpage with additional information about the early help service and links to other sources of support. On the page they were able to submit their details to request help from early help.

Webpages were designed to reassure readers about the relevance and benefit of engaging with the service and included quotes from people who have accessed help previously.

Methodology

Initially, participants were those who had been offered early help through contact with the front door team, this was then extended to those who had been written to. However, due to changes in the way early help organised their data, we were unable to include everyone who was offered early help. They were randomly assigned to either the treatment condition or the control condition. Those in the treatment condition were sent the follow-up texts (including link to the leaflet), while those in the control condition did not receive these materials. We then measured the difference in decline rate of early help support between these two groups.

The impact

The results from the intervention trial showed a significant difference when compared to early help data previously provided by the council. While the acceptance rate of the early help offer found in our scoping phase analysis was 72 per cent, within our trial sample (that is, for intervention and control group combined) it was only 2 per cent. Changes to data collection and classification within the council also resulted in a considerable reduction to the number of families that were within scope for the trial when compared with the numbers used for power and sample size calculations. Therefore, the results from the trial were inconclusive due to a significantly reduced sample size.

It is important to note that the absence of a clear result from the trial does not indicate that the intervention was ineffective. It is merely unproven / unclear whether the text intervention is effective. Despite the absence of a conclusive result from the trial, the wider research and insight gathering from the project has generated significant understanding of the challenge and opportunities to increase take up of early help.

Several learning points were gleaned from the project:

The rate with which the offer of early help support is turned down vary significantly according to: the referrer (contact source), where the family live (local area deprivation) and time of the year (seasonality).

Despite the considerable resource invested, there is no evidence to suggest that front door staff making phone calls to families is effective at encouraging the take up of early help support. Take-up of the early help offer arising from phone calls from front door staff is extremely limited. Given the high resource requirements of these calls, there’s no evidence that they offer value for money and considerable efficiencies could be realised by deploying this capacity elsewhere.

There is evidence from research literature – but the trial findings have not been able to determine this – that the communication channel used to offer early help support is also a factor in whether families accept or reject it.

Contacts that originate from the police are responsible for the majority of recommendations for early help – significantly and disproportionately more than might be expected.

Recommendations for early help that come from a police referral are far more likely to be declined, whereas recommendations from schools are much more likely to be accepted (only 7 per cent declined).

There is a perception among social care practitioners that designated safeguarding leads (DSLs) – particularly in schools but also more widely – are receiving inaccurate or misleading information and guidance around where and when to make referrals to a children’s safeguarding contact (CSC).

There appears to be limited shared understanding and clarity of what early help is among practitioners across services. This is particularly evident among the police who appear to have limited understanding of what the early help support offer entails, its benefits and how to communicate it effectively to families.

The police appear to have a process which limits the opportunities to engage with families effectively. Child concern notifications (CCNs) are seen as the only tool available to the police and are consequently used indiscriminately.

How is the new approach being sustained?

The early help service is currently undertaking a review of pathways and communications materials which the research will inform. The ongoing use of text messages at ‘the front door’ is also being actively considered.

Work is also underway to implement a new case management system for early help services where messages about recording practice and data quality will be picked up.

Lessons learned

Despite the absence of robust quantitative trial results to determine whether or not the intervention was effective, there has been considerable learning from the project for the early help service, and how Newcastle City Council can use these learnings as opportunities to intervene.

A more considered approach to change and innovation can aid understanding of ‘what works’

Changes were made between the scoping phase and the trial delivery and during the trial delivery that significantly impacted on both the sample size, the categorisation of families in scope and how data were recorded. These changes severely reduced the overall sample size – on which the trial design and sample size calculations had been based – which ultimately undermined the viability of the trial to detect a statistically significant intervention effect.

Local government inevitably has to deal with constant change and pressure to develop new approaches and improve effectiveness and efficiency. However, making multiple simultaneous changes to a particular service can severely limit the ability to understand what works (or doesn’t). In this instance, changes following the project scoping and design (prior to the trial commencing) and during the trial delivery, severely impacted on any meaningful assessment of effectiveness (and indeed the viability of the trial itself). A more measured approach of incremental and iterative innovation – test, evaluate, learn, adapt – would make it far simpler to accurately determine what difference individual changes are making and enable the adoption of effective approaches and allow ineffective ones to be abandoned.

Using data to generate insight and inform decision-making and service design

We observed a strong approach to data analysis and analytics within the council, with accurate data being produced in a timely manner. However, the analytics can only be as good as the system on which they are based and the information that is captured within in. Although changes were made to improve data collection during the course of the project, it is clear that data resides in multiple locations which can impair the ability to extract key service delivery insights. It also appears that data are not always being used to inform service design and that the ‘right questions’ are not always being asked which direct how data are interrogated.

One example of this is the use of phone calls as a way to encourage take up of early help. Regardless of whether families were within the intervention or the control group of our trial, the evidence suggested extremely limited take up of early help arose as a result of a phone call from front door staff. Given the high level of resource required to undertake these calls, there is no evidence to support the assertion that this is an effective approach for the council to take. It would appear from the evidence available that this capacity would be far better deployed elsewhere.

Opportunities to adopt more overt customer-centred service design

The benefits of a customer-focused approach to designing services are that it ensures systems and processes are based on the perspective of those we want to engage with a service. By placing the interests and perspective of customers at the centre of how services are designed and delivered, we increase both effectiveness and engagement. At present it appears that aspects of early help do not routinely consider the perspective of families that it wishes to engage with the service.

For example, the provision of services within office hours may have benefits from a delivery perspective but it is not based on the needs or interests of families. While front door staff are seen as personable, friendly and efficient, this is irrelevant when services are only offered at times that are inconvenient for families. The service would benefit from providing itself outside of normal office hours, so that families who work or have other daytime obligations have opportunity to access the services at a convenient time. Whilst we recognise that this may have resource implications for the Council, delivering a service that is less effective simply because it is more cost-effective focuses more on the service providers rather than the people who will actually be engaging with the service.

Employing a more resonant and personable approach to communications and messaging

When we want to encourage someone to do something, we ought to ask ourselves – ‘what is in it for them’? Considering this question helps us to understand how to frame our communication in a way that is more likely to be effective at motivating the reader to respond as we would wish.

Having reviewed the letters used by early help to communicate with families; it is apparent that the tone, style and design could be strengthened in the following ways:

- The current content needs to be more personal, and less formal

- The title is most frequently ‘If you need this information in another format or language, please contact the sender.’ Arguably, this is neither the title, nor the most important part of the content, despite occupying a very prominent position on the page. The most salient or eye-catching part of the letter should be utilised for the most important information.

- Content needs to promote benefits of response or engagement, rather than just acting functionally.

- The content makes no specific reference to the family circumstances. Whilst this may be conscious in order to avoid sensitive information being seen by others in the household, it increases the sense of impersonality and potentially ‘invisibility’ – meaning people may feel it is easy to disappear ‘within the machine’. Therefore, the content should be personalised in order to make families feel 'seen', rather than just part of a process.

- While the content is clear about steps the family might take to be in touch, it misses the opportunity to show empathy or to reassure the recipient about the positivity of taking such action.

- The messenger (‘the council’) is austere and distant, at a time where it should be making an effort to be friendly and welcoming.

There are also several ways communications and messaging could be improved through design and style. Effective use of boxes, headlines, titles, keywords that are highlighted (using bold type or colour) and other formatting devices like these encourages the reader to recognise what is important on a page. It provides signalling which allows the reader (subconsciously) to understand where they ought to focus their attention.

Such techniques can also help to embed key messages in a way that is salient to the recipient. These include:

- Boxing out key information – such as contact names/numbers/websites – placing these in the top right-hand corner of a given page/slide. This technique does feature in the leaflet but there is potential to increase impact.

- Images – there are very few images used in the leaflet (none in the letters), it is clear that effort has been made to include a mix of ethnicity and gender. It may be useful to include some images that are clearly from Newcastle as a way of stressing the local relevance.

- Colour coding might be a useful tool to assist navigation of the information within the leaflet.

Contact

Stephen Foreman, Informatics Manager, Newcastle City Council

[email protected]