How to support effective outcomes

Working together for effective outcomes for safeguarding concerns

November 2019 – January 2020

In late 2019 three national workshops were held in London, Leeds and Birmingham and attended by over 250 participants. A follow up workshop was held in January 2020 to ‘reality check’ and develop the themes identified in the national workshops.

Workshop participants explored the themes about safeguarding concerns from a range of perspectives, including those of health and social care providers, the police, health and adult care commissioners, adult social care, and Multi-Agency Safeguarding Hubs (MASH). People who use mental health services and the situation of people who are homeless and multiply excluded were considered.

Workshops were structured around presentations from the perspectives of referrers of concerns and those who receive concerns. Participants explored the themes from the presentations via table-top discussions and case studies. The perspectives of people who have experienced abuse and neglect was represented by a podcast with follow up discussions.

Organisations represented at the workshops

- Acute health trusts

- Adult Social Care

- Clinical Commissioning Groups

- Care Quality Commission

- Department of Health and Social Care

- Healthwatch

- Local Government Association

- MASHs

- NHS Digital

- NHS England

- Police forces

- Probation services

- Social care providers

- Mental health trusts

- Safeguarding Adults Boards

Key themes

There is a potential lack of equal access to adult safeguarding, dependent upon how safeguarding concerns are defined in a particular area.

Underpinning issues were thought to be:

- how people and their circumstances were perceived by either referrers or front line safeguarding decision makers.

Examples given included people who experienced not being believed because of their mental health status (‘psychiatric disqualification’); or the myth of ‘lifestyle choice’ applied to people who services were unable to engage in support, whose addictions/mental health/self-neglect were thought to be a choice rather than a result of trauma or other negative experience, and people who ‘sleep rough’. Included within these issues was the misuse of the provisions of the MCA (2005) to define the mental capacity of a person as a factor in being able to protect themselves from abuse or neglect, ignoring the care and support needs which made it difficult for the person to do so.

- People living in circumstances unfamiliar to main stream adult social care

Examples given included people who are homeless or living in temporary accommodation; or people living in ‘closed environments’ such as mental health units. Abuse or neglect risks being seen as part of the circumstances people live in rather than a concern which needs an adult safeguarding response, the person, and the impact of the harm on them, is lost

- The absence of a person-centred approach and understanding of the impact of abuse and neglect can lead to a ‘hierarchy of abuse’

Examples given included emotional abuse or hate incidents that are not seen as important as criminal acts. Domestic abuse responses could be confused by harm being minimised as a result of perceptions about the dynamics of intimate or family relationships or about how much choice and control could be exerted by the person being abused.

- The systems and ways of working used at the front line mean that the person is not always at the centre

Multi agency partners talked about a ‘tick box culture’ with little opportunity to discuss what was happening with the person, and use of recording systems that prevented the use of relationship based approaches, producing a false assurance about what was understood and limiting responses informed by professional curiosity.

the need for collaborative decision making and support in both preventing and finding responses to abuse and neglect whether within responsibilities set out in Section 42 (S42) of the Care Act (2014) or through other powers or multi agency arrangements

Workshop participants advocated strongly for collaboration between all agencies in sharing risk and finding solutions together. Ideas about ‘collective responsibility’ rather than seeing adult social care as the lead agency, together with the importance of systems to support collaborative working, featured in debates. Numerous examples were given of partnership approaches to preventing abuse and neglect, detailed in appendices 3 and 4

the need for support for that collaborative working including clear guidelines, shared language /definitions, opportunities for dialogue, mutual respect and understanding of roles and responsibilities

Multi agency partners identified some of the barriers to collaborative working:

Relationships and expectations

- Poor relationships between agencies, in particular a lack of respect for social care providers. These relationships can be typified by a lack of trust and ‘blame culture’, there is no ‘parity of esteem’ between agencies.

- safeguarding, typically, health care providers were expected to make decisions about what to refer as a concern, social care providers were given guidelines but were often asked to consult on or notify all incidents. Participants had concerns about a lack of transparency or accountability regarding health providers decision making, and the need to step back from an overly paternalistic approach to social care providers.

- There is a lack of confidence across partnerships about whether health provider pathways, including serious incident reporting and use of the care programme approach to manage risk, are being used appropriately or whether safeguarding concerns are not reliably reported, particularly regarding incidents that happen within acute and mental health trusts.

- A lack of respect can extend to a failure to feedback decisions about concerns, this extends to most referrers. Preventative and responsive partnerships cannot thrive without dialogue.

- Dialogue between referrers, decision makers and internal or external subject matter experts is needed to promote understanding, problem solve and clarify expectations

- Participants from the third sector felt particularly marginalised, they frequently found that the circumstances of the people they worked with and the role of their agencies was overlooked, with little relationship or dialogue with adult social care their connection with adult safeguarding was tenuous.

Shared language and definitions

- The language used in guidance is thought to be ‘social care orientated’ and hard for external partners to understand.

- All participants, including police, social care and health providers and the third sector reported confusion about what a safeguarding concern is and what to report. The police work with people who are vulnerable in different ways, who and what would represent a safeguarding concern is hard to identify with existing guidelines.

- Social care providers reported that the CQC and local authority had different expectations of what should be reported and that there were potentially negative consequences for them attached to not reporting accurately.

- There is no agreed definition of ‘poor practice’ or what is a ‘quality issue’ in health and social care agencies.

- There is a lack of clarity in many agencies about what is a concern about a person’s welfare, and what is a safeguarding concern.

The way forward

Participants gave clear messages about what was needed to address the themes above:

As safeguarding partnerships at frontline and strategic level we need:

- well understood and commonly owned safeguarding aims

- a shared language and understanding about safeguarding concerns

- agreement about what circumstances expose people to abuse and neglect

- clarity about information sharing

- opportunities for dialogue to promote skills and knowledge sharing and an understanding of each other’s organisational culture, priorities and demands

- collaboration underpinned by the principle of collective responsibility. This supports multi-agency risk sharing and problem solving, determining effective responses together, agreeing follow up and doing it, sharing responsibility for making sure that the person has the support they need.

The six safeguarding principles at the frontline and the SAB; the wellbeing principle in practice

In considering what might constitute a safeguarding concern and how to respond flexibly to individual circumstances, the six principles are at the heart of front line practice. They might be understood by front line staff as:

Empowerment

- I am confident in my own role and the role of others Prevention

- I recognise the potential for harm and take action to prevent the possibility arising. Proportionality

- I am aware of the range of options available to address risk of harm according to individual circumstances

Protection

- I can identify the circumstances in which I need to refer a concern

Partnership

- I take up opportunities for dialogue and working together

- I engage with others in problem solving and sharing risk

The Care and Support Statutory Guidance (Paragraph 14.13, Care and Support Statutory Guidance, DHSC, 2020) also specifically highlights these principles as a means of support for SABs as well as organisations in carrying out their roles.

Checklist against the six principles

The role of the SAB in supporting collaborative partnerships to ensure consistency and effectiveness in defining and working with safeguarding concerns

Empowerment

- The SAB is assured that front line staff are confident in their own role and the role of others and that citizens are confident in referring concerns.

- The SAB is actively developing a culture of respect and positive learning across all agencies in its area.

- The SAB is assured that staff and citizens recognise the potential for abuse and neglect and know how to take action to prevent the possibility arising. Staff and citizens are aware of resources and options to prevent abuse and neglect.

Proportionality

- The SAB has agreed, shared and supported the pathways available to address the risk of abuse and neglect and know that these are being supported and used regularly by all agencies.

Protection

- The SAB is assured that all staff and citizens understand when they need to consider referring an adult safeguarding concern and who they can consult with if necessary.

Partnership

Across the partnership the SAB has agreed

- common aims

- common definitions and language to describe adult safeguarding, safeguarding concerns and safeguarding enquiries.

Frontline staff and citizens across the SAB area have opportunities for dialogue and working together, including co-production.

SAB creates, supports and seeks assurance on the expectation of collective responsibility at the frontline, staff engage in problem solving and sharing risks together. Staff have an escalation route to use to support collective responsibility for effective outcomes.

Accountability

The SAB has systems which promote accountability and transparency, including audit systems which pick up on the level of effectiveness of collaborative working, and decision making in the context of safeguarding concerns. It seeks assurance of partners taking collective responsibility; working together in responding to issues that may constitute safeguarding concerns. There are mechanisms in place to support the SABs transparency and accountability to citizens in their area, including adults with care and support needs.

Wellbeing in practice

A checklist for all frontline staff: How are you supporting the adult’s wellbeing in the way that you work with them?

Personal dignity (including treatment of the individual with respect)

What does this mean for the individual?

- Everyone treats me with respect and makes sure that my dignity is upheld at all times.

- My thoughts and wishes are heard and acted on with respect

Physical and mental health and emotional wellbeing

What does this mean for the individual?

- People are interested in my emotional and mental health as well as my physical wellbeing.

- I have options to promote and maintain my physical, mental and emotional health that are acceptable and accessible to me.

Protection from abuse and neglect

What does this mean for the individual?

- I am supported by the service that is right for me, I am supported by staff I trust and I am living with people I can get along with.

Control by the individual over day-to-day life (including over care and support provided and the way it is provided)

What does this mean for the individual?

- I am asked what I would like at all times, my choices control what happens in my daily life.

- I am supported to make decisions when this is difficult for me.

Participation in work, education, training or recreation

What does this mean for the individual?

- I have a range of opportunities to engage and participate at the level I want to.

- My participation has meaning for me and improves the quality of my life.

Social and economic wellbeing

What does this mean for the individual?

- I have a social life at the level I want.

- I have enough money to support my everyday needs and to provide opportunities I value.

Domestic, family and personal

What does this mean for the individual?

- I can enjoy my private life in the way that I want to.

- I get support to maintain and develop my relationships as much as I choose to.

Suitability of living accommodation

What does this mean for the individual?

- I live in accommodation which is safe, warm and meets my individual needs.

The individual’s contribution to society

What does this mean for the individual?

- Self-esteem, I feel I am an active and valued member of my community.

Case study A – Julie

This case study concerns domestic abuse and the approach that might be taken by a psychological therapist working with the person concerned in

- thinking through whether to make a safeguarding concern referral

- the steps to take as part of the process of making the referral.

Case outline

Julie is 35. She lives with her husband of 10 years. They have no children. She goes to see her GP and tells the GP she is depressed and anxious and would like some medication to help. She confides in the GP that her husband refuses to give her any money and won’t allow her friends to visit or Julie to leave the house. Julie appears to be suffering with low moods and speaks of an increased dependence on alcohol. Julie further discloses emotional, physiological, physical, financial abuse and coercion.

The GP prescribes anti-depressants and a referral to Talking Therapies. Julie agrees for the referral to be made. The psychological therapist decides to call the local authority as she thinks that this is a safeguarding adults concern.

Decision-making in this case, reflecting the approach set out in the suggested framework

In considering whether to make a safeguarding concern referral to the local authority the psychological therapist will need to consider two criteria, does Julie have

(a) needs for care and support (whether or not the authority is meeting

any of those needs) and is she (b) experiencing, or is at risk of, abuse or neglect "

Julie has disclosed that she is being abused by her husband, and therefore meets criteria (b); she has also disclosed a number of factors which would indicate she might be in need of care and support, she has developed mental health issues and is becoming dependent on alcohol to manage her distress. These two aspects could indicate that Julie does have care and support needs. There may be other aspects of Julie’s wellbeing that are concerning the psychological therapist which should be considered in terms of their impact on Julie’s potential need for care and support.

The therapist has decided to telephone the local authority to discuss the situation, a useful step which will begin a dialogue focused on creating a person-centred and collaborative approach to supporting Julie.

Useful questions for the therapist to consider

- How will I explain my concerns to Julie?

- Am I able to tell Julie what adult safeguarding is and why I think a referral needs to be made?

- Will the risk of abuse be increased by having this conversation with Julie?

- What does Julie want to do?

- Does she want to refer herself? With my support?

- Does Julie consent to me referring the concern? If not – are there risks to Julie’s vital interests sufficient for me to override the need for her consent? Are there risks to the public? We know that Julie and her partner have no children, but does her partner have children from a different relationship?

The therapist may well meet regularly with Julie and is in a good position to explore some of the areas that can usefully be included in a referral and in discussions about a concern. Not all referrers are in this position, but if the information can be ascertained this will involve Julie at the earliest opportunity in a discussion about her understanding of the abuse and risk she is experiencing.

Areas to explore and include in a referral

- What is working well in supporting the Julie’s wellbeing, what are the strengths in her life

- Where are the gaps in how she experiences wellbeing?

- The concerns the therapist has and why she thinks getting further help is important no

- Confirming the impact that the abuse is having on Julie and any others in the situation

- What has Julie tried so far, what worked, what didn’t or in fact made things worse

- What does Julie think the risks are? What does the therapist think the risks are?

- What does Julie think needs to happen next?

- What is the impact of the ‘complicating factors’ in the situation – being subject to coercive control? Risks from the abusive partner

- Discuss and agree any relevant historical information that should go into the referral

Working through all of the questions above means that Julie is fully involved in making the decision about referral, increasing her sense of control about what she believes may help.

Case study B: Mr and Mrs Lewis

This case study shows:

- working with a member of the public who is making a referral about a safeguarding concern

- considerations of abuse or neglect of another adult living in the situation, or their carer.

Case outline

Mr Lewis is showing signs of early dementia, he is 80 years old and lives with his wife at home. Their daughter is concerned that both are now in a position where they are unable to look after themselves, being both frail and struggling with mobility. Mr Lewis is adamant that he is fine and that there is nothing wrong with him. His daughter does believe there are significant changes in his behaviour, he is not the same man that she had come to know as her father. He had refused to attend a memory clinic appointment, which was made for him a few months previously and the clinic had said that they could not do anything until he gave his consent.

Mrs Lewis has confided in her daughter that he shouts at her, her daughter is getting more and more worried that his temper may ‘turn physical’. Mr Lewis recently purchased a bed from cold callers at the house. This bed cost him nearly £5,000 – they did not need a new bed as they had not long purchased a new mattress for their existing bed. It was out of character for him to spend a large amount of money like this. Mr Lewis’ daughter contacted the bed company and they had promised to get back but have not done so as yet. In the meantime, the bed had been delivered and the old bed taken away. The cheque for the bed had been cancelled but there were still concerns that Mr Lewis might be bullied into buying it. All of this is making Mrs Lewis very poorly and she is finding day-to-day life unbearable.

Decision-making in this case, reflecting the approach set out in the suggested framework

The Lewis’ daughter has read a leaflet about adult safeguarding in the local surgery.

She thinks that both her parents meet the criteria for referring a concern as both have:

(a) needs for care and support (whether or not the authority is meeting any of those needs) and both are (b) experiencing, or is at risk of, abuse or neglect"

Useful questions to discuss with the Lewis’ daughter

- What has prompted her concerns now?

- Has she talked with either or both of her parents about her concerns?

- Does she have enough information to explain to them what adult safeguarding is?

- If she has raised her concerns with them, have either or both of her parents consented to her referring a concern?

- How can we support her to talk with her parents about what is happening and what the best way forward might be for them in terms of a referral?

It may be useful to acknowledge with the Lewis’ daughter that a lack of consent may need to be overridden as the behaviour of either Mr or Mrs Lewis impacts on the wellbeing of the other adult in the situation.

Further areas to explore and include in a referral

Remembering that the process from referral to working with in the s42 duty can be fluid rather than linear, we may find that S42(1) is initiated during the taking of a referral from a member of the public. We would anticipate that a telephone discussion takes place with the Lewis’s daughter. If she is with her parents and there are no risks of exacerbating the situation it might be possible to talk with one or both parents to gain their initial thoughts. Alternatively, these areas may best be left until a face to face meeting can be had with the family, or with each individual, to explore the situation and their perspective further. The questions below can be asked of the family, or with the Lewis’s daughter initially before exploring further with her how to engage her parents in a full discussion. Useful areas to cover will be:

- Wellbeing – what do the Lewis family think is working well, what supports do they have, where are the gaps in managing their everyday life, what is the quality of their life, what would they want to change if they could?

- What further supports do they think they need? What is the impact of potential financial exploitation on the Lewis’s?

- What is the impact of Mr Lewis behaviour on Mrs Lewis? If Mrs Lewis is afraid of or avoiding Mr Lewis, how does this impact on his wellbeing?

- Does it increase the risk of neglect of his needs?

- What does each family member think the risks are if the situation continues?

- What has each family member tried so far, what worked, what didn’t or in fact made things worse. What do they think needs to happen next? Is there any relevant historical information that should go into the referral?

Mrs Lewis may be undertaking the duties of a carer for her husband. She also appears to be an adult with care and support needs, so may be referred for consideration of the s42 duty in her own right.

If Mrs Lewis does not have care and support needs her wellbeing, including her safety, as a carer should still be considered as described within the statutory guidance. It may also be possible to undertake an enquiry even although the s42 duty does not apply. It should be remembered that if a carer is being abused by the adult they are caring for there may be a risk that the adult’s needs are neglected as the carer finds it difficult to continue to support them.

Case study C – Peter

This case study concerns applying the core messages in the framework to

- working with staff in a provided service

- working with a representative two people with care and support needs.

Case outline

Peter, a 26-year-old man with severe autism and learning disabilities attends day care for three days per week. He was travelling to the day centre with x, who also attends the day centre, sitting next to him as usual. X reached over to Peter and pinched him on the left arm.

The bus attendant immediately stopped the transport and separated both service users to different seats. Distraction techniques were used whilst x was advised that his actions were not appropriate. Once at the day centre, Peter and x were kept apart by their 1:1 members of staff.

Peter was initially distressed but soon calmed down. He was checked for injuries and he had a red bruise with the imprint of three fingers from contact. This was recorded on a body map.

Decision-making in this case, reflecting the approach set out in the suggested framework

The day centre manager considers referring the incident as a safeguarding concern. Peter certainly appears to meet the criteria for referring a concern as he has:

(a) needs for care and support (whether or not the authority is meeting any of those needs) and both are (b) experiencing, or is at risk of, abuse or neglect"

We do not yet know the emotional impact on Peter, but this may also be evident in the days to come.

Useful questions for the day centre manager to consider

- Does Peter have the mental capacity to decide to consent or not to a safeguarding referral being made to the local authority?

- Are there accessible resources that can be used to explain the concerns to Peter to support him to understand as much as possible and to make a decision?

- If he does not have the mental capacity to decide to consent or not, who does he wish to be his representative?

- If he does not have the capacity to make this decision, does he have an appropriate representative who will act in his best interests?

Peter’s mother was identified as the appropriate representative by the day centre manager, she has been told about the incident and about the actions taken to minimise risk, including Peter and x being kept apart by staff members. She is happy with the measures put in place. Peter’s mother is reported as consenting to this being addressed through safeguarding adults procedures and has said she is willing to be his representative. Peter has been attending the day centre for many years, and the manager thinks that they have a positive and trusting relationship.

Further areas to explore and include in a referral

What has the impact of the incident been on Peter? The day centre manager referred the incident to the local authority the same day that it occurred, good practice recommended in many policies and procedures. But we will not know if there is any long-term impact on Peter for some time, he may now be unhappy to get onto the bus or to be near x. The referrer could consider the reactions Peter has had to any previous incidents to indicate that he may be emotionally upset about the incident in the future.

The context of the incident is important, what is the known historical relationship between Peter and x? Is this relationship important to Peter and would he wish to continue sitting with x? Or is he indicating that he does not wish to be near him? Peter’s wishes, whether they can be articulated by him or not, are an important aspect of the referral and of considering a person centred rather than a risk averse approach.

Further information about x may also form part of the referral, but only on a basis of the need to know whether other adults, or children, are at risk from his behaviour. A legally literate response applies to x as well as Peter, and x will need to be asked for consent to share further information about himself, and the MCA process followed if there is a reasonable suspicion that x does not.

Following the steps above means that the referral reflects the legislation underpinning adult safeguarding, including the provisions of the MCA 2005. The referral is also person centred, moving away from describing an event and instead exploring the meaning of the incident to Peter and perhaps to those around him including x.

Peter and his representative are said to have a trusting long-term relationship with staff at the day centre, a collaborative response between the provider and local authority will be important in resolving matters. Conversations and timely feedback between all the agencies involved will support the best and potentially most effective outcome for Peter.

Bournemouth/Poole/Dorset/ Multi Agency Risk Management (MARM) meetings

MARM is a locally developed and agreed protocol placed in the context of the broad safeguarding umbrella. MARM has no statutory basis but is a formal framework to enable agencies to share information where there are concerns about an individual living in the community, and to formulate a response and explore solutions quickly. Any agency can host and facilitate a MARM if it has concerns, the local authority safeguarding adult team may also advise that a MARM should be held if the threshold for a Section 42 Enquiry is not met. MARMs are convened by Fire and Rescue Service, Police, the housing agency, substance misuse service, probation services, or Environmental Health, not just the local authority or health services.

The MARM can support individuals to achieve maximum wellbeing as well as considering the risks they are exposed to. It allows agencies to meet with the individual or their advocate using a formal framework to identify and share risk, whilst maximising the opportunities for case management concerning a specific individual. Members of MARM meetings have the same authority and responsibility to obtain support in difficult or complex circumstances as if the matter was being dealt with via a Section 42 Enquiry or any other case-based concerns or issues. This can include getting legal advice about the Court of Protection, talking with colleagues in domestic abuse services or considering a capacity assessment or best interest decision making if there is sufficient doubt about a person’s capacity to make decisions about the concerns that led the MARM to be convened.

The MARM process is underpinned by the core messages in the LGA/ADASS concerns framework: it is legally literate, and has the six safeguarding principles, the wellbeing principle and a person-centred approach at the centre. The process is about collective endeavour and collective responsibility. There are clear governance processes to promote accountability of all agencies.

Plymouth Creative Solutions Forum

The Creative Solutions Forum (CSF) was developed from a recognition of the need to establish a way to support individuals, staff and agencies to understand and manage risk fluidly. The CSF partnership includes statutory, provider, community and voluntary services in its core membership, and collaborates to consider creative options for people with highly complex needs and presentations that require a multi-agency response and where other single or multi-agency processes have been exhausted. This often includes people with a combination of substance misuse and serious physical or psychiatric co-morbidities, homelessness, people who are self-neglecting and people presenting high levels of risk to themselves and the community. It may also include people that are on an end of life pathway, often people who are homeless and/or using substances.

The CSF provides a co-ordinated multi-agency response to need, where a range of professionals plan an integrated response together, sharing ownership of outcomes and jointly managing risk. The creates a bespoke offer to meet an individuals’ needs, which could include alternative care options, out of hour’s activities, whole family therapeutic or behavioural support, support in the home and parent/carer support, and planned inpatient services. The CSF will also seek to identify gaps in provision to meet need which may be used to inform commissioning plans.

The CSF is a well-established example of a mechanism that encourages creative partnerships between providers and commissioners, which place the person at the centre of planning, and shares responsibility for risks and outcomes. The core messages of collaborative endeavour and collective responsibility are at the heart of the work of the CSF. The cultural change created by the CSF has been developed by the Plymouth Safeguarding Adults Board to change the relationships within the SAB see appendix 5 case study E.

Bristol Golden Key Creative Solutions Board (CSB)

Golden Key is a partnership between various organisations, charities and service providers across Bristol, working together to improve services for Bristol citizens with the most complex needs. The Creative Solutions Board was established in August 2019 to undertake two main functions:

To meet and discuss in detail, individuals where the current response is not working and creatively action/plan a different solution, with the person at the centre To use this individual learning to inform how the whole system might need to change and flex to deliver better outcomes.

Members of the Board include senior managers from the council, CCG and Police, with adult social care, adult safeguarding and housing represented, mental health services, and the voluntary drug and alcohol and homelessness services. Cases are presented by frontline workers with advice and support from experts by experience, both bringing expertise and real-life issues to Board members.

The CSB has some distinct features which reflect the core messages in the concerns suggested framework. There is a strong link between frontline practitioners, experts by experience and strategic managers with the two former groups contributing to strategic learning about how systems are working. A key component of the CSB’s development has been the building of collaborative relationships between members and the agencies they represent. These relationships, based on a deeper understanding of the role, responsibilities and values of each organisation, are now extending beyond the CSB itself. These relationships are beginning to encourage new ways that individuals relate to each other and consequently changing the ways in which their organisations interact.

Decision support tool example – Oxfordshire Safeguarding Adults Board

There are a range of decision support tools in use nationally, many of which have been based on a tool developed by Oxfordshire SAB. Decision support tools can be helpful, but risk decision making by case study if the core messages of this suggested framework are not incorporated into the guidance. Local protocols need to use the messages in the framework to set out the core ingredients for making every decision in each individual set of circumstances. The Oxfordshire SAB decision making support matrix includes examples from practice but also underlines aspects of the core messages. It encourages consultation on whether to refer a safeguarding concern if there is uncertainty; it seeks to apply some of the legislation; it indicates other possible pathways through which issues might be addressed; it recognises the importance of recording what on the surface may not be identified as safeguarding concerns, in order to enable the identification of patterns of concerns.

Decision support tool – Isle of Wight Safeguarding Adults Board

This decision support tool is grounded in the core messages of the concerns suggested framework. It is detailed and contains the vital legal literacy, principles and person-centred approach needed to support effective decision making about an individuals’ circumstances. The tool also has extensive and useful information on decision making about some of the more common concerns in provided services, medication errors and falls.

Solihull Safeguarding Adults Board - Concerns between two people with care and support needs

Solihull SAB has developed detailed guidance on responding to concerns involving two people with care and support needs. The guidance explores the system around the two people as well as the need to understand individual’s needs and perspectives.

Preventative partnership case examples

Participants at the national workshops suggested a number of examples of partnerships between agencies aimed at promoting wellbeing and preventing abuse and neglect.

Serenity Integrated Mentoring (SIM)

A small number of repeat callers who were struggling to cope with the challenges of their lives were identified as creating up to 40 per cent of the demand on all emergency services across the UK. Recognising that NHS staff alone were not equipped to manage some of the most extreme levels of behaviour, specialist, integrated mental health care and policing teams were formed to provide a unique blend of nursing care and behavioural management.

SIM carefully selects and trains police officers and police staff alongside their clinical colleagues. Together they learn about the trauma and triggers that lead to high intensity behaviour, they discuss how best to manage risk and how to ensure that the service user does not keep on repeating the same high risk, high harm behaviour. It is demanding and intensive work but can bring significant breakthroughs in the lives of people whose behavioural risks are likely to result in them entering the criminal justice system or even worse, dead from accidental suicide.

Find out more about Serenity Integrated Mentoring (SIM)

National Trading Standards (NTS) Scams Team

National Trading Standards (NTS) Scams Team is funded by National Trading Standards and is hosted by Surrey County Council. The team was founded in 2012 to tackle the problem of postal, telephone and doorstep scams. The team works across England and Wales with trading standards and partner agencies to investigate scams and identify and support those who fall victim to them.

The team receives information from a range of partner agencies who identify potential victims of scams. The team then contacts the local trading standards service of those silent victims and enters into partnership agreements with them. These partnership agreements include a variety of ways in which local authorities can work together to intervene and support their identified victims. Information is gathered about victims and best practice, which enables the team to inform local authorities and partner agencies of the most effective ways to work with and support scam victims.

A1. Collaborative approaches to create, maintain and review guidance – The East Riding of Yorkshire

The East Riding of Yorkshire share their top tips on developing, reviewing and updating guidance on decision making about common safeguarding concerns identified in provided services.

Their local care sector forum represents around one hundred and thirty independent provider organisations and has a full day meeting three times a year. Slots at these forums are used to talk through the local operational guidance on what to refer to adult safeguarding. When updating and reviewing the guidance, forum attendees worked in small groups to work through scenarios, identifying what they thought should be referred in to safeguarding and what they should manage in-house. They also had to document their decision and feedback. All points raised which were not clear were then clarified further in a review of the documentation. Feedback is also gathered from providers about how the guidance is being used and how helpful it is.

A2. Collaborative approaches to create, maintain and review guidance - Suffolk

The Suffolk Safeguarding Adults Framework was developed by the multi-agency partners of Suffolk Safeguarding Partnership in consultation with a number of organisations across Suffolk. It was developed in response to an independent review of Safeguarding Adults to assist practitioners and their organisations with a common understanding of the indicators of abuse.

Consultation sessions ran across the county and open invites were cascaded via SAB members through various appropriate forums or channels. There were representatives from many different organisations across health, police, social care, providers, advocacy, voluntary organisations, trading standards, fire service, Healthwatch and others.

Following the consultation everyone was given a “you said, we did” sheet showing what was incorporated from the sessions and what was not, giving the reasons why some comments were not adopted. The feedback was also on the SAB website which demonstrated that organisations were fully consulted with and decisions related to the documents were transparent. The framework is hosted by the SAB website and people are encouraged not to print it but to use it as an online resource that is evolving and kept up to date by SAB business support staff. Updates can come from any organisation or individual, but the changes are agreed by the original small working group before being adopted, again feeding back to people if the change is not made.

The Framework has a very extensive list of support services and referral agencies. The list is used in all areas of safeguarding activity, from “pre” safeguarding concerns through to supporting adults whilst an enquiry is taking place. Providers, front door staff find it useful in day to day business.

During training on the Framework participants are asked about services that may have been forgotten that they are aware of. In particular the resources relating to self-neglect and hoarding are growing rapidly. The Suffolk Framework is a continually developing, interactive demonstration of creative and collaborative approach that maximises the experience and knowledge of all agencies.

A3. Collaborative approaches to create, maintain and review guidance - Leeds

Leeds SAB worked with nine ‘citizen groups’ to produce practice guidance for professionals working in adult safeguarding. The guidance develops themes from the six safeguarding principles and provides checklists to guide professionals in all aspects of safeguarding work.

Citizen expectations are integrated through all aspects of Leeds SAB Adult Safeguarding policy and procedures.

B. Plymouth SAB - Impact of learning from the Creative Solutions Forum (CSF) – a reflection from the Plymouth SAB Chair

The Plymouth SAB Chair noted the collaborative and creative culture of the CSF, a forum of statutory, provider and voluntary agencies who work together with the aim of creating bespoke support around individuals who are in situations of high risk and where usual responses have failed (see appendix 4 case study B). The CSF challenged the ‘hand offs’ pervading the local safeguarding system and some areas of partnership working, where thresholds had become a reason for inactivity or moving big ‘S’ safeguarding to little ‘s’ safeguarding.

The PSAB saw the emerging practices of CSF as an opportunity to reset and fundamentally re-construct a new way of engaging senior partners in its board structure. The challenges identified by the CSF champions were seen as a reflection of the safeguarding ‘eco-system’ as well as the way the board had been working.

Following a review of SAB business and informed by the culture and energy of the CSF forum, the PSAB began operating in a very different way:

- thematic approach to each board meeting

- paper and process light

- operational practice issues brought directly to the partnership board members via operational staff presentations ‘in the room’

- significantly more challenges across the tables and more authentic contributions

- alignment of agendas to avoid duplication- SAFER and Trauma Informed assurance theme runs through every meeting

- SAB business cleared and discharged through the SAB Executive group.

CSF was the key catalyst for these changes and challenged us to shape our work differently. Through the expertise, knowledge and talent of key individuals working in different agencies there was an authentic desire to see how partners could challenge the norm and agitate change in creative ways the ‘art of the possible’. The focus is bespoke-user and service centric. The environment this has created enabled the PSAB to move in a similar direction, with little resistance.

C Devon Safeguarding Adults Board - auditing and assurance

The Devon Safeguarding Multi-Agency Case Audit aims to assess multi-agency practice. The purpose of the audit is to draw out best practice and learning and share it with colleagues across Devon. Devon Safeguarding Adults Board completes a Safeguarding Multi-Agency Case audit to understand what is working well or not working well for adults and/or their families/carers. Outcomes from the audits enable recommendations to be made to improve the way that different agencies work together to support adults and develop safeguarding practices and adults safeguarding experiences.

Where possible Safeguarding Multi-Agency Case Audits will try to ensure that a professional who knows the individual is present so they can give a detailed picture of the individual. Front line practitioners are involved in case conversations, the practitioner is asked to reflect on the safeguarding principles as part of the conversation and to contribute to the Safeguarding Multi-Agency Case Audit as a whole. By ensuring and encouraging conversations with all those involved enables the opportunity to reflect safely together, on what worked well and why.

Support for developing audit questions and methodologies

D Gloucestershire Safeguarding Adults Board (GSAB) Resolving Professional Differences

The GSAB has adopted a number of key principles to enable difficulties between agencies to be resolved quickly and openly in the best interests of the adult. These are intended to foster learning cultures of respectful challenge and parity of esteem between agencies:

- Respond positively to feedback – it is not personal. Issues have been raised because there are concerns about the level of risk for an adult(s). Being able to positively accept challenge is equally as important as being able to rise to a challenge.

- Seek to resolve any professional disagreements at the lowest possible level as part of everyday working practice and within the timescales laid out in this guidance.

- Encourage others to challenge or question your own practice, to ensure healthy challenge becomes part of professional and learning cultures.

- Wherever possible, discussions should take place face-to-face or by telephone. Try to avoid the use of email alone to raise a challenge. However, it is good practice to follow up your conversation by email to document the discussions that took place.

- The tone of challenge should be one of respectful enquiry, not criticism – be curious and remain curious until you understand and accept the reasons behind the decision that has been made or an alternative decision has been reached.

- Challenge should always be evidence based and solution focused.

- Be persistent and keep asking questions.

- Discuss your concerns with the named safeguarding lead within your organisation or through supervision arrangements.

- Always keep a written record of actions and decisions taken in line with your own organisation’s information governance and record keeping policies.

- REMEMBER, you are acting in the best interests of the adult and they must always remain central to your discussions and decision making.

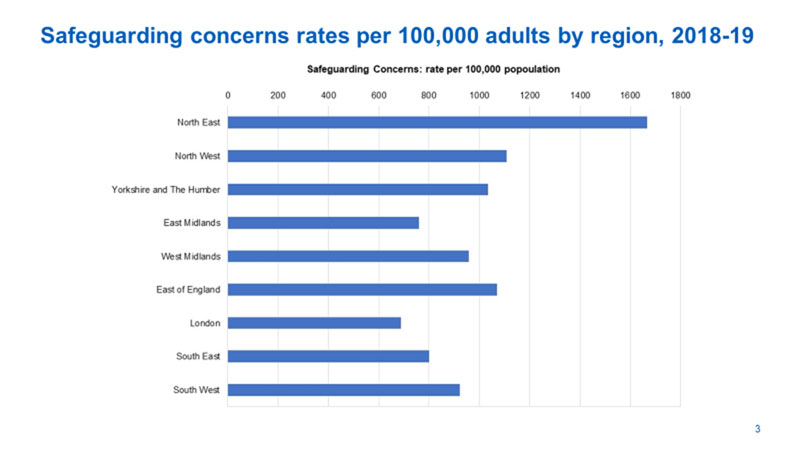

The 2018/2019 Safeguarding Adults Collection return continues to show a wide variation in what local authorities are counting as ‘safeguarding concerns’. Table 1 below shows the regional variation per 100,000 population. Demographic factors alone cannot count for this variation which ranges from approximately 700 concerns per 100,000 population (all London region) to over 1,600 per 100,000 population (North East region). If individual local authorities are compared the range is still wide, differences do not appear to be regional, but local.

Safeguarding concerns rates per 100,000 adults by region, 2018-19

In 2018 NHS Digital developed a survey to ascertain how local authorities defined key elements of adult safeguarding activity in their 2017-2018 SAC submission. 78 local authorities (51 per cent) responded to the survey. Of these, 38 local authorities reported that they had some form of ‘triage’ or filter to redirect safeguarding concern referrals before they reached an adult safeguarding team. These concerns may well have been diverted appropriately but will not be reported within the local authority SAC return.

Seven local authorities reported that concerns are assessed by a safeguarding team, but those that are ‘not safeguarding’ or represent quality concerns are diverted to care management or quality/contract compliance teams, again these concerns will not be reported as part of the local authority SAC return.

At what point in a process of filtering a referral is recorded as a ‘concern’ is a key influence on how many concerns are reported in the SAC. In addition, how work is electronically allocated in the local authority recording and allocation systems may well influence whether a referral can be recorded as a ‘concern’ before it is recorded as ‘care management’ or ‘quality team’ referral. Filtering for the purpose of allocation will influence the number of concerns reported to the SAC.

Agreed ways of working may also influence whether something is recorded as a concern by the local authority. For example, evidence from workshop participants and from the tools submitted indicates that some local authorities have guidelines that specify what should and should not be reported as a concern by providers, local authorities without such guidelines may have a higher level of concerns per population.

Does it matter that the reporting of concerns to the SAC is not consistent across local authorities?

Accurate and consistent reporting supports a number of activities connected to the principle of ‘accountability.’ At a practice level, accountability to individuals extends to making sure that they are aware of what the response has been to a concern about them. A response that is not supported by the s42 duty may well be the best response to their circumstances, but individuals should know what that response is. Adults with care and support needs, as well as the public in general, will wish to know via the SAB annual report how the local authority has responded to safeguarding concerns, and to understand the narrative behind the number of concerns recorded.

Safeguarding Adults Boards, local authorities and the DHSC can use consistent data to understand and monitor how local authorities are meeting statutory duties. In addition to SAC data local authorities and SABs should collect supplementary, local data and information to support their understanding of how concerns are understood and recorded, and to improve local monitoring of the quality of safeguarding activity.

During the writing of this framework the Covid-19 pandemic has generated and will continue to generate significant implications across all sectors for safeguarding adults. Responding to Covid-19 as it develops will undoubtedly require making difficult decisions under new and exceptional pressures with limited time, resources, and information.

On 25 March 2020 the Coronavirus Act 2020 came into force. This and the Care Act easements guidance allow a local authority to trigger ‘easements’ to the Care Act (2014). However, safeguarding duties cannot be eased. Where a local authority triggers easements, it means that the Care Act (2014) duties to assess and meet eligible needs of adults, young people transitioning to adult services and carers can be amended. Local authorities are expected to observe the Ethical Framework on adult social care which was produced alongside the guidance. Additionally, it is important to state that safeguarding adults remains a statutory duty - to keep everyone safe from abuse and neglect, with a clear role in avoiding a breach of human rights.

Government guidance is clear that local authorities should only trigger easements if it is essential that they do so, due to the pressure from coronavirus. The local authority must go through an established process to decide this, including approval by the Director of Adult Social Service. The government’s stated expectation is that even after triggering the easements, local authorities will do everything that they can reasonably do to continue to meet need as they would under the Care Act (2014). Local authorities will still be expected to carry out proportionate, person-centred care planning and they must meet needs wherever required to avoid a breach of a person’s human rights.

The focus on human rights is significant and needs must still be met in order to avoid any breach of human rights. The case study ‘Howard’ in section 2 of this framework indicates the importance of balancing conflicting duties that may be owed in a human rights context.

There are important Care Act (2014) duties that remain intact irrespective of ‘easements’. These include duties to:

- promote individual well-being (s1)

- provide suitable information and advice (s4)

- involve the person when revising care and support plans (s 27(2))

- safeguarding (s42 to s47)

- refer for and provide advocacy (s67 and s68).

This last point is significant in the context of Making Safeguarding Personal. The duty to provide advocacy is still in place and is not affected by easements. The Coronavirus Act (2020) does not alter the Care Act (2014) safeguarding duties, s42 (1) (2) to make necessary enquiries when there is reasonable cause to suspect that an adult with needs for care and support is experiencing or at risk of experiencing abuse or neglect from which the person is unable to protect him or herself. This obligation applies whether or not the local authority is meeting the person’s needs for care and support (which may now encompass individuals whose care may be provided differently, reduced or withdrawn during the emergency period).

The core messages in this framework, with its emphasis on core principles, collective endeavour, clarity and transparency are consistent with principles set out in the Coronavirus Act (March 2020) and the Care Act Easement Guidance (March 2020) and Ethical Framework on adult social care (2020). This framework relating to safeguarding concerns is in step with the principles and messages behind the Care Act (2020) easements guidance which promote:

- approaches that are: collaborative, person centred (consider the individual’s wellbeing), apply core statutory principles

- the ‘ethical framework’ for the provision of adult social care which is consistent with safeguarding adults core principles.

The rationale for decisions must be transparent and clearly evidenced against statutory principles, including an understanding of the significant factors, impact, and level of risk in each individual situation. There needs to be flexibility and proportionality but only where necessary and appropriate.

In this emergency social care decisions should not only be compliant with the law; they should also go with the grain of professional codes and guidelines. Where adverse outcomes of social care decisions are challenged (by those in need as well as by social workers) – the reference points will be these twin principles (law and professional practice) rather than the primacy of arbitrary (and narrow) budgets, performance indicators and rigid internal rule books."

It is uncertain what the impact of Covid-19 and the measures taken in response to it will be on the levels and types of safeguarding risks for adults. Safeguarding Adults Boards (SABs) and leaders are encouraged to understand the local impact of Covid-19 on safeguarding activity. In accordance with the role of the SAB, they can seek assurance of partners’ responses to the challenges of the pandemic, for example, in relation to:

- How information and data can support understanding the nature and impact of Covid-19 on safeguarding adults locally, for example responses to the potential increased risks of specific safeguarding issues (such as domestic abuse and fraud/scams) during the Covid-19 pandemic.

- Oversight of Section 42 duties in relation to safeguarding and in the context of the need for proportionate responses in current pressures.

- Effectiveness of partnership working during the emergency both in terms of responses and preventive measures (ie assurance that people are safeguarded whether through a safeguarding adults pathway or through another route, whether or not a safeguarding concern triggers a statutory enquiry).

- How is the voice of all partners heard about safeguarding issues arising from current circumstances?

- If Care Act easements are used, what impact does this have on safeguarding activity locally?

Specific questions arising in the context of the Covid-19 pandemic, in relation to adult safeguarding and this safeguarding concerns framework could include:

- Do Local Authority practitioners have sufficient understanding of human rights and human rights assessments to recognise possible human rights breaches? Are they able to make fine judgements that require balancing sometimes conflicting duties?

- Is there evidence that the framework supporting decision making on the duty (S42) to make safeguarding enquiries is being set aside in the context of other pressures? Is practice reverting to operating blanket ‘thresholds’ in order to limit the number of safeguarding concerns being addressed and enquiries undertaken?

- Is there evidence of an ongoing focus on the quality and transparency of decision making in identifying, referring and responding to safeguarding concerns?

- Is local recording and analysis of safeguarding adults concerns continuing to be reported or developed to enhance information provided by the SAC, including information about those people whose needs do not meet the duty to carry out a S42(2) enquiry? This may include a focus on increases in certain types of abuse during the coronavirus outbreak (and the need to understand trends created by this)?

- In the context of Care Act easements, is there any impact on safeguarding adults of any duties that are suspended?

- How are Directors of Adult Social Services, PSWs and adult safeguarding leads promoting the ethical framework and support staff in working with this empowering framework in their safeguarding practice?

National publications

England Protocol on Pressure Ulcers

Guidance

SCIE: Overview of what is safeguarding adults

General NHS England

General: Birmingham Safeguarding Adults Board

Clear definitions of common safeguarding terms

Doctors

General Medication Council: Adult Safeguarding

British Medical Association: Adult Safeguarding Toolkit

General practitioners

Royal College of General Practitioners (2019) Adult Safeguarding Toolkit

Housing providers

SCIE ‘At a glance’ 66 (2018) Safeguarding Adults for Housing staff

Police

Guidance currently being developed (2020).