For people with an intellectual and developmental disability (IDD), the COVID-19 pandemic saw a traumatic loss of routine, activities and contact with family and carers that was hard to understand and to cope with. In addition, the increased risk of dying from the disease is significant for people with IDD, compared to the general population.

This forms part of the LGA’s A Perfect Storm report, published April 2021.

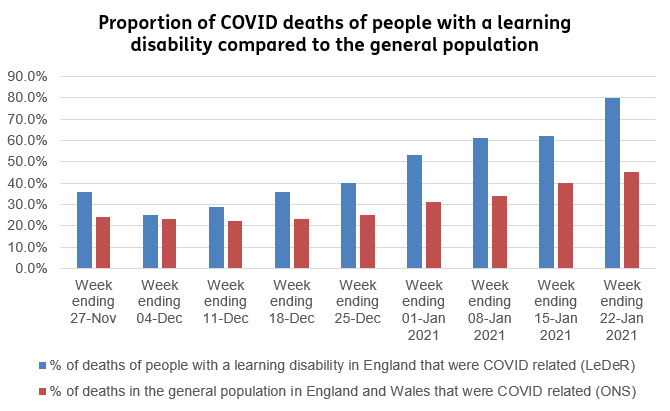

Data released by Mencap in February 2021 in the graph below revealed that the death rate from COVID-19 amongst those with a learning disability rose steeply during December and January. The data refers to deaths of people with a learning disability in England that were reported to the Learning Disability Mortality Review (LeDeR) – although it is not a requirement for deaths to be reported so many could be missed.

The data of COVID-19 deaths of patients with a learning disability from LeDeR and the Office for National Statistics (ONS) also shows that in every week since the end of November, people with a learning disability have died from COVID-19 disproportionately compared to the general population. This disparity between the proportion of COVID deaths grew dramatically throughout December and January.

In the graph below, Mencap reveals that COVID-related deaths for people with a learning disability were dramatically higher than the general population in England and Wales (Eight in 10 deaths of people with a learning disability are COVID related as inequality soars).

Earlier in the pandemic, a PHE report COVID-19: deaths of people with learning disabilities found that after standardising for age and sex, 451 per 100,000 people registered as having a learning disability died with COVID-19 between 21 March and 5 June 2020; a death rate 4.1 times higher than the general population of England (109 per 100,000). However, researchers estimated the real rate may have been as high as 692 per 100,000, 6.3 times higher, because not all deaths in people with learning difficulties are registered on the databases from which this data was taken.

The report found that deaths were also spread much more widely across the age spectrum among people with learning disabilities, with far greater mortality rates in younger adults, compared to the general population. The death rate for people aged 18 to 34 with learning disabilities was 30 times higher than the rate in the same age group without disabilities."

The age-standardised COVID-19 death rate was higher for men than for women with learning disabilities but slightly less than the difference for the general population and for hospital patients without learning disabilities.

The impact of ethnicity was also noted: the proportions of COVID-19 deaths in people with learning disabilities that were of a person from an Asian or Asian British group, or a Black or Black British group were around three times the proportions of deaths from all causes seen in these groups in corresponding periods of the two previous years, and greater than the proportion in deaths from other causes in 2020.

People with IDD are likely to have difficulty recognising symptoms of COVID-19, or following government advice about getting tested, self-isolation and social distancing as well as infection prevention and control. It may also be more difficult for people caring for them to recognise the onset of symptoms if these cannot be communicated. Many people with IDD have difficulty accessing health care in ordinary times and adapting to changes in consultations with healthcare professionals will have been particularly challenging. Remote consultations via telephone or video-link, as well as professionals wearing personal protective equipment cannot have been easy.

Media reports about COVID-19 in care homes mostly concentrated on older people but there are many younger people living in residential homes because of their learning disability and/or physical disability. The isolation for them, combined with a lack of understanding of the pandemic and its restrictions will have made this particularly hard. Seeing family, the other side of a window, without being allowed physical contact will have been confusing and distressing for many.

The PHE report found that between March and June 2020, COVID-19 accounted for 54 per cent of deaths of adults with learning disabilities in residential care, slightly less than for people with learning disabilities generally, but still much more than in the general population. This is likely in part to reflect the greater age, disability and possible underlying health problems of those in residential care."

People with IDD are more likely to have physical health problems such as obesity and diabetes. Certain kinds of learning disability, such as Down’s syndrome, can make people more vulnerable to respiratory infections, which can increase their risk of dying from COVID-19

As well as the risk of increased mortality from COVID-19, lockdown and service restrictions have had a significant impact on people with IDD - on behaviours and routines as well as severely limiting their ability to act independently and autonomously. Occupational activity for this group of people has been severely curtailed, further impacting on their independence.

There has been an enormous strain on families and carers for whom the intensity of the demands of continual caring, often with work commitments being managed alongside full-time caring responsibilities. In some cases, adult relatives with IDD who normally live in residential care services (with one to one or greater support) were sent to live with the family at home (with no additional support). Without timely professional support many carers experienced excessive strain and a reduction in their psychological wellbeing.

Some families manage complex packages of support, often employing staff. This means they are having to deal with the employment issues as well as physically maintaining the care and support of their relative and ensuring the environment is COVID safe for family and workers.

The pandemic has meant routine healthcare is now largely delivered by telephone or video consultations. Lack of regular physical health reviews for those with IDD is a concern as they identify unmet needs and implement interventions to improve health outcomes.

Research by Tromans et al, in Priority concerns for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities during the COVID-19 pandemic, investigated the expectations of people with intellectual disabilities and/or autism during the pandemic and made recommendations based on their feedback. Priority concerns centred around:

- Mental health and challenging behaviour – including a risk of relapse of or further deterioration in challenging behaviours, risk of misattribution of symptoms and behaviours in IDD, over prescription of medication and access to mental health services.

- Physical health and epilepsy – including risk of delayed presentation to services to address physical health complaints, risk of physical complications from possible COVID-19 infection, risk for not monitoring epilepsy-related concerns including seizures and seizure related injuries.

Social circumstances and support – including social isolation, access to social support services, financial hardship, risk of abuse/neglect, loss of respite care, change in accommodation/breakdown of placements.

The report highlights the importance of retaining and employing specialist staff trained to work with those with IDD, but many may have been redeployed during the most pressured waves of the pandemic.

Local authorities will be working closely with third sector colleagues to support those with IDD, especially where they also face financial hardship. It will be important to preserve placements and respite care.