Executive Summary

This research was commissioned by the Local Government Association in December 2019 in response to a growing concern that more and more children were missing out on their entitlement to a formal full-time education. The purpose of this research is to look at the issue of children missing education in its entirety. Drawing on evidence provided by local authorities, school leaders and parents we try to understand who the children are who are missing out on a formal full time education, how many children fit this description, what evidence there is for the long-term impact of children missing education and how local and national government might work together to address this issue.

The statutory definition for Children Missing Education states that “Children missing education are children of compulsory school age who are not registered pupils at a school and are not receiving suitable education otherwise than at a school.” However, one of the clear conclusions of this research is that this relatively narrow definition risks some significant blind-spots in our collective understanding of the cohort of children missing education.

We are therefore proposing, for this research, a wider definition of children missing education – any child of statutory school age who is missing out on a formal, full-time education. By ‘formal’, we mean an education that is well-structured, contains significant taught input, pursues learning goals that are appropriate to a child or young person’s age and ability and which supports them to access their next stage in education, learning or employment. By full-time we mean an education for at least 18 hours per week.

A common theme that has emerged from this research is that the way that the range of existing policies and guidance around pupil registration, attendance, admissions, exclusions and education otherwise than at school comes together is not seamless. While parents, local authorities and schools all have both responsibilities and powers to ensure that children receive the education to which they are entitled, some significant omissions in the current legislation mean that it is possible for children to slip through the net.

Children missing education do not form a homogenous group and are not always easy to identify. Our research has suggested that there are multiple routes whereby children may end up missing out on a formal full-time education, and eight main ‘destinations’ where these children may be found. These include a variety of both formal and informal education settings, at home receiving different forms of educational input or none at all, in employment or simply unknown to those providing services in the community. This complexity helps to explain why the numbers of children missing out on their entitlement to education might be routinely underestimated and why it has historically been a challenge to construct legislation and guidance that ensures that no children miss out on the education which is their right, by law.

Nationally, there is a distinct paucity of any comprehensive, reliable data outlining the numbers of children who are missing extended periods of formal, full-time education. However, the research evidence that does exist strongly suggests that the number is rising. Without a clear sense of how many children in England might be missing out on their entitlement to a formal full time education it is very difficult to be precise about the scale or nature of intervention that might be needed either locally or nationally to address the issue. We have therefore used this research as an opportunity to use existing data published nationally, and complementary data held locally, to develop an estimate for the number of children who may be missing out on a formal full-time education.

Our best estimate is that in 2018/19, more than a quarter of a million children in England may have missed out on a formal full-time education which equates to around 2% of the school age population. However, this is just an estimate. Depending on how one defines ‘formal’ and ‘full-time’ it could be closer to 200,000 or over 1 million. The main concern is that we simply do not know if children and young people are getting their entitlement to education, and we cannot be certain of the risks to which they are being exposed by not being in full-time education.

The evidence provided by those who engaged directly in this research all points to vulnerable children being far more likely to miss out on formal full-time education than their peers. In our data sample, local authorities shared some of the characteristics that were common to the cohort of children missing education. The large majority of these included those with social and behavioural needs; those with complex needs and no suitable school place available; those with medical or mental health needs; and of those with mental health needs, those accessing CAMHS either as an in-patient or through services in the community.

There is not a single factor that explains the growth we have seen in children who are not receiving suitable, formal, full-time education. Instead, the evidence we gathered suggests that it is a combination of three sets of factors that, taken together, have given rise to this trend. These are:

- the changing nature of the needs and experiences that children are bringing into school;

- pressures and incentives on schools’ capacity to meet those needs; and

- the capacity of the system to ensure appropriate oversight of decisions taken regarding children’s entry to and exit from schools.

Put simply, wider societal factors have meant that children are arriving in schools with a combination of needs, often linked to disruption in their family lives, at a time when schools’ capacity to respond is more limited and the way in which schools’ effectiveness is judged has focused more sharply on the academic, and less on the inclusive, aspects of education. This has created a situation where the pressures on schools and families are manifesting themselves through parts of the education policy framework that were not designed to deal with these issues – the potentially inappropriate use of elective home education, part-time timetables and condoned non-attendance, permanent exclusion and alternative provision, for example. While LAs have the responsibility to maintain oversight of the suitability of the education received by school-age children, there is a mismatch between the scope of these responsibilities and the capacity and means to carry them out at a detailed, case-by-case level such that there can be assurance that all children missing from formal, full-time education are receiving a suitable education.

The impact of children missing out on formal full-time education is felt by the children themselves, by families and by society. For individual children, the negative implications can include slower progress in learning, worse prospects for future employment, poorer mental health and emotional wellbeing, restricted social and emotional development and increased vulnerability to safeguarding issues and criminal exploitation. Having children out of education also places enormous strain on families, both emotionally and financially. Furthermore, the lifetime costs to the state of a young person not in education, employment or training have been shown to be very significant. Children missing out on formal full-time education can also be detrimental to communities, reinforcing stereotypes and increasing isolation.

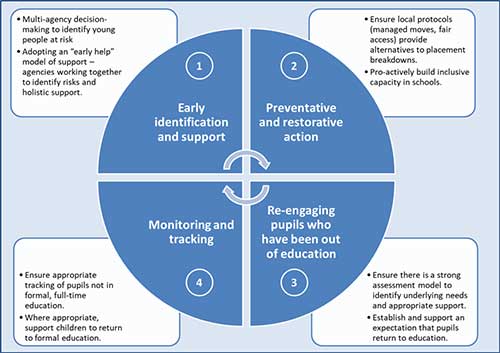

Many of the councils which took part in our research were taking a strategic and proactive approach to identifying, preventing and reengaging children missing education, in the broadest sense of the term. The key actions that they are taking are captured in the graphic below:

There is already considerable good practice in the system and opportunities from local authorities to learn from each other. However, local government would be the first to acknowledge that the safety net that they provide to ensure that all children, but particularly the most vulnerable, do not miss out on their entitlement to education is stretched to capacity. Furthermore, the omissions in the current powers that local authorities have to exercise their statutory duties create opportunities for some children to slip through the net. The rising numbers of children not in education, combined with diminishing resources at all points in the system, has created a very fragile equilibrium.

As a outcome from this research, we would therefore recommend that the Department for Education considers the following actions, that would support local government to discharge their duties in respect of ensuring all children are able to access a formal full-time education more comprehensively:

- Raise the profile of children missing formal full-time education

Our research has shown that the current statutory definition of children missing education does not capture many of the children who are missing out on a suitable education. Furthermore, the lack of published data pertaining to this cohort makes them less visible in terms of policy and unknown in terms of outcomes. We would therefore recommend that the Government adopts a broader definition of children who are missing out on formal, full-time education, collects and publishes data on the numbers of children who meet the definition and tracks the long-term destinations and outcomes for children missing formal full-time education.

- Resource local authorities adequately to fulfil their responsibilities in relation to ensuring all children receive a suitable education

The evidence gathered through this research suggests that the lack of capacity and resources within local authorities is one of the key barriers to ensuring that all children receive a suitable formal, full-time education. The work of identifying children who are missing education and then bringing together families, schools and other education providers to broker a solution that secures ongoing education for those who have dropped out of the system is a painstaking and labour-intensive task. There is no substitute for individual, careful case-management. In the current financial climate, few local authorities have the resources needed for the true scale of that task.

- Create a learning environment in which more children can succeed

It is a finding of this research, and many other similar projects, that in the current climate schools maintain a focus on inclusion despite the accountability and performance incentives, not because of them. There is a lot that Government could do to give schools back the flexibility they need to create an appropriate learning environment in which more children can succeed. This could include recognising and rewarding greater curriculum breadth; rewarding schools for inclusive practice through the accountability system; investing in pastoral and mental health support and significantly developing trauma informed practice in schools.

- Strengthen the legislative framework around electively home educated children

In April 2019 the Government consulted on changes to primary legislation that would strengthen the oversight and mechanisms for reassurance around electively home educated children. It proposed a new duty on local authorities to maintain a register of children of compulsory school age who are not at a state funded or registered independent school and a new duty on parents to provide information if their child is not attending a mainstream school. The purpose of these changes would be to enable better registration and visibility of those educated other than at school. The evidence collected through this research suggests that both changes would be beneficial in strengthening the oversight afforded to vulnerable children within this cohort and we therefore recommend that the necessary legislative changes are made at the first opportunity.

Download

Children Missing Education report (PDF)

If you would like a fully accessible version of this document as a pdf, please contact [email protected].