Background and introduction

The Insight Project was developed to create a national picture regarding safeguarding adults’ activity during the COVID-19 pandemic. The first report (COVID-19 Adult Safeguarding Insight Project: Findings and Discussion) provided a picture of how safeguarding adults activity in England was affected by the initial stage of the pandemic and first lockdown, up until June 2020. This second report provides information on safeguarding adults activity up to December 2020.

Key messages

- The Second Insight report summarises safeguarding adult’s activity data and information from 101 Councils in England.

- The COVID-19 pandemic and accompanying lockdowns had an unprecedented and extraordinary impact on safeguarding. Rates of safeguarding concerns during 2020 were overall higher than 2019. There was a sharp decline in the rate of safeguarding concerns as lockdowns started, followed by steep increases immediately as lockdowns ended. These increases were often sustained until the following lockdown period. However, not all councils followed the national trends.

- Councils who reported increased numbers of concerns during the lockdowns said that these were from emergency services, family, friends, neighbours, volunteers, and health partners. Only 29 per cent of councils who sent qualitative data saw no change.

- Nationally, there were moderate increases in the rates of domestic abuse, self-neglect and psychological abuse reported in safeguarding activity in 2020, compared to 2019.

- Councils reported receiving a high level of safeguarding concerns regarding adults who did not have care and support needs, nevertheless they were at risk of multiple categories of abuse and neglect and they were supported without going down a safeguarding pathway.

- Safeguarding enquiries increased in a person’s home during the lockdown period and overall, there was a decrease in safeguarding enquiries in both nursing and residential home settings during the pandemic period. Councils commented on reduced access by professionals, families, and friends to care homes.

- Increased levels of complexity in safeguarding activity undertaken were reported. Councils described the challenges that social distancing brought to the safeguarding enquiry process, including being unable to undertake essential face-to-face visits. The practicalities in progressing safeguarding enquiries became more difficult. which made Making Safeguarding Personal more challenging. The COVID-19 pandemic and lockdowns created complexity and barriers in how people could report as well as experience abuse and neglect.

- There was considerable variation between councils’ experiences regarding safeguarding activity in the pandemic and many variables were at play including: the number of ‘anxiety referrals’ received; proactive/preventative approaches taken; local demographics; the local provider profile; how safeguarding concerns and Section 42 enquiries are recorded; partnerships dynamics to enable effective multi-agency working; localised lockdowns coming into force; the complexity of safeguarding concerns and enquiries themselves and COVID-19 related safeguarding issues emerging and manifesting across various abuse and neglect categories.

- Councils adapted to maintain safeguarding roles and responsibilities during the COVID-19 pandemic, regardless of the situation that they were facing. Very specific barriers arose from the COVID-19 pandemic including reduced face-to-face contact, significantly increased workloads. In response Council innovated and adapted their communication methods, developed their approached the Section 42 enquiry process; improved how they worked with other agencies; increasing the frequency of meetings using technology; created new partnerships; increased professional curiosity; worked flexibly; and proactively to create bespoke solutions to issues that emerged. Councils developed new strategies, anticipated change, were proactive and adaptive, based on local circumstances and learning from experiences in the first lockdown,

- The first Insight Project report has been used by councils, Safeguarding Adults Boards (SABs), and partners to benchmark, reflect and identify issues within their locality to support learning and change.

Rationale

The COVID-19 pandemic and accompanying lockdowns have had an unprecedented and extraordinary impact on all aspects of day-to-day life and behaviours. There are ongoing concerns about how people with care and support needs may experience different or more abuse or neglect due to these changes. Insight into the impact of the pandemic on safeguarding activity can firstly, describe what is happening, secondly, inform future activity to mitigate increased or different risks of abuse and thirdly, offer a national picture for the varied and shared local experiences. Data and intelligence provide evidence, both to emphasise the importance of safeguarding adults and influence policy and decision makers.

It is important to understand what has happened, and continues to happen, to respond to changing safeguarding needs, learn lessons for future COVID-19 outbreaks and consider the longer-term impact of the pandemic. It is hoped that this insight and data improve understanding of the impact of COVID-19 locally and nationally and informs responses to people with safeguarding needs as well as assist planning for the future.

Throughout the pandemic, there have been concerns that safeguarding issues were not being identified and reported, due to reduced ‘face-to-face’ contact between adults with care and support needs and professionals, families and friends, especially, but not only, regarding people living in care homes. In community settings, there continues to be increased concern regarding the ongoing impact of social isolation and the changing risks of abuse for people with care and support needs (eg increased self-neglect, new scams regarding COVID-19 testing and immunisation). There continue to be concerns about ‘surges’ in safeguarding demand and activity when lockdown restrictions are eased and face-to-face social and professional contact restarts and intensifies. The monthly data, alongside the qualitative intelligence, collated in these insight reports describes the median experience amongst councils but also how councils may have had a very different set of patterns and trends.

The Safeguarding Annual Collection (SAC) - the annual mandatory data return for recording safeguarding activity operated by NHS Digital - captures information about safeguarding activity at the end of each financial year, although during 2019/20 a voluntary six-month ‘snapshot’ was undertaken of a sub-set of SAC data for April-September 2020. The six months ‘snapshot’ data from 2020 has been incorporated into the findings described in this report. Usually data is collected and collated by NHS Digital over the months following collection and published at the end of that calendar year ie data for 2020/21 is due to be published in November/December 2021. It does not provide a picture of changes during the year. The annual data shows how 2020/21 compares to 2019/20 but will not show how the different phases of the pandemic and lockdowns have impacted on safeguarding activity. This is the gap that the Insight reports aim to fill.

It was recognised that councils were, and continue to be, under considerable pressure to meet other mandatory data requests from central government during the COVID-19 pandemic, which meant it might be difficult to respond to the requests for safeguarding data. This Insight Project was therefore entirely voluntary and flexible. The proposal for the Insight Project has been supported by Local Government Association (LGA) and Association of Directors of Adult Social Services (ADASS), through the safeguarding workstream of the Adult Social Care Hub (joint LGA and ADASS), Care and Health Improvement Programme (CHIP) and with support from the co-Chairs of the National Principal Social Workers Network, safeguarding leads at the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) and the National Network of Chairs of Safeguarding Adults Boards.

Given the multiple variables that impact on safeguarding activity, inferring causal relationships and patterns that would apply to all councils is problematic. This report looks to indicators and factors that provide a narrative that show overall trends. It is intended to provide a national picture for strategic reflection, offer a framework for analysis of the local experience in comparison to the national trends described and capture the complexities of the impact of the pandemic on safeguarding activity in England during this period.

First Report findings: summary

The first report included information covering the period between January 2019 and June 2020, this showed that safeguarding concerns dropped markedly during the initial weeks of the first COVID-19 lockdown period, only to return to and then exceed expected levels in June 2020. The trend of safeguarding enquiries showed a similar decline during the initial weeks of the COVID-19 lockdown period and upturn in June 2020, although the June upturn was not as great. This could be due to a number of factors including: the time frames for undertaking and completing safeguarding (section 42) enquiries, lower levels of data contributions for June 2020; and activity in June not having caught up with the backlog of safeguarding concerns generated in the first lockdown period.

Analysis of the percentage distribution of types of abuse within safeguarding enquiries indicated that domestic abuse increased slightly overall, and significantly within some councils, as well as slight increase in psychological abuse and self-neglect. The percentage of safeguarding enquiries where the risk is in the individual’s own home had increased markedly related to the confinement of people in their homes. Safeguarding enquiries where the risk/safeguarding incident was in care homes had decreased as a percentage over the same period, confirming fears that there was a reduction in activity and reporting due to lack of visiting and outside scrutiny in those environments during the first lockdown period.

Methodology: quantitative data

As with the first report, requests were made for local insight and data on safeguarding activity on a voluntary basis from councils in England for the period up to December 2020. This voluntary collection of safeguarding activity compares monthly levels over time, and between equivalent months in 2019 and 2020, and month by month trends. As with the first voluntary collection, a simplified subset of the Safeguarding Adult Collection was used, with a series of questions included to elicit further insight and intelligence on local trends and changes to provide the quantitative findings. The pro forma was circulated to councils in the form of an Excel template, which they filled in with the relevant data and returned to the LGA. This data was collated through LG Inform and put into charts and tables for this report. The qualitative data was collated and analysed to generate the findings.

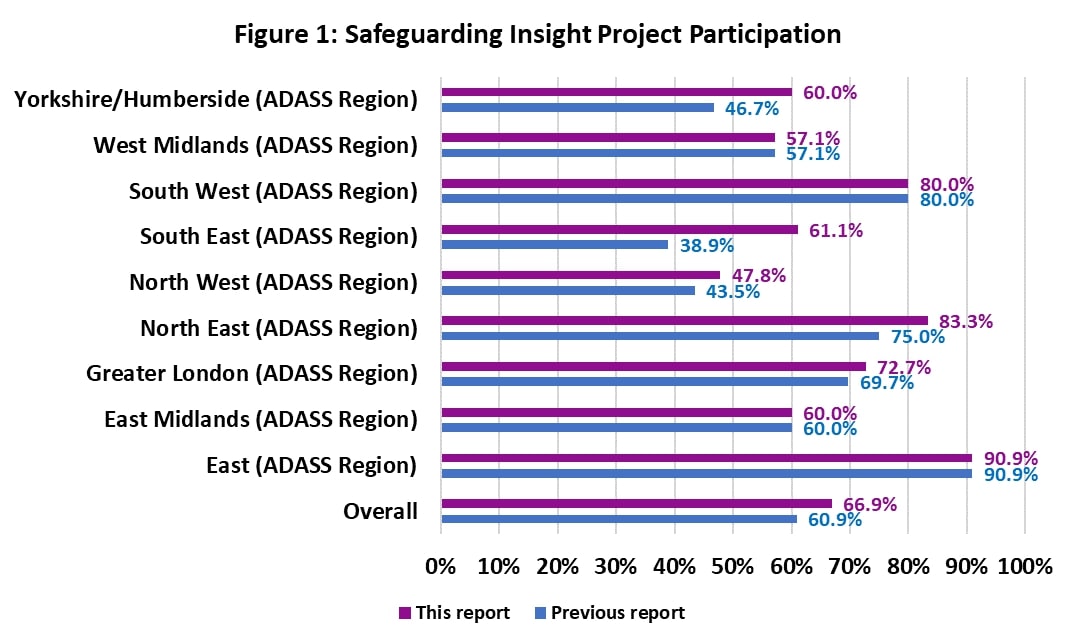

The first report presented data covering the period from January 2019 to June 2020, receiving responses from 92 councils – around 61 per cent of all single tier and county councils in England. This new second report presents data from January 2019 to December 2020 and is based on the responses of 101 councils – around 67 per cent of applicable councils. This means that an additional nine councils began to participate at this stage of the project. This response rate varied by region, but in general those regions with the lowest response rates in the previous report tended to increase markedly in the latest round of data collection (see Figure 1).

It was recognised that councils were, and continue to be, under considerable pressure to meet other mandatory data requests from central government during the COVID-19 pandemic, which meant it might be difficult to respond to the requests for safeguarding data. This Insight Project was therefore entirely voluntary and flexible. The significant number of volunteers providing information to the project suggests that there was a widespread interest in describing and understanding the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdowns on safeguarding activity. The lower response to the second request for data up to December 2020 (75 of 151 Councils) coincided with the height of a national surge in COVID-19 infections and the major lockdown in January 2021.

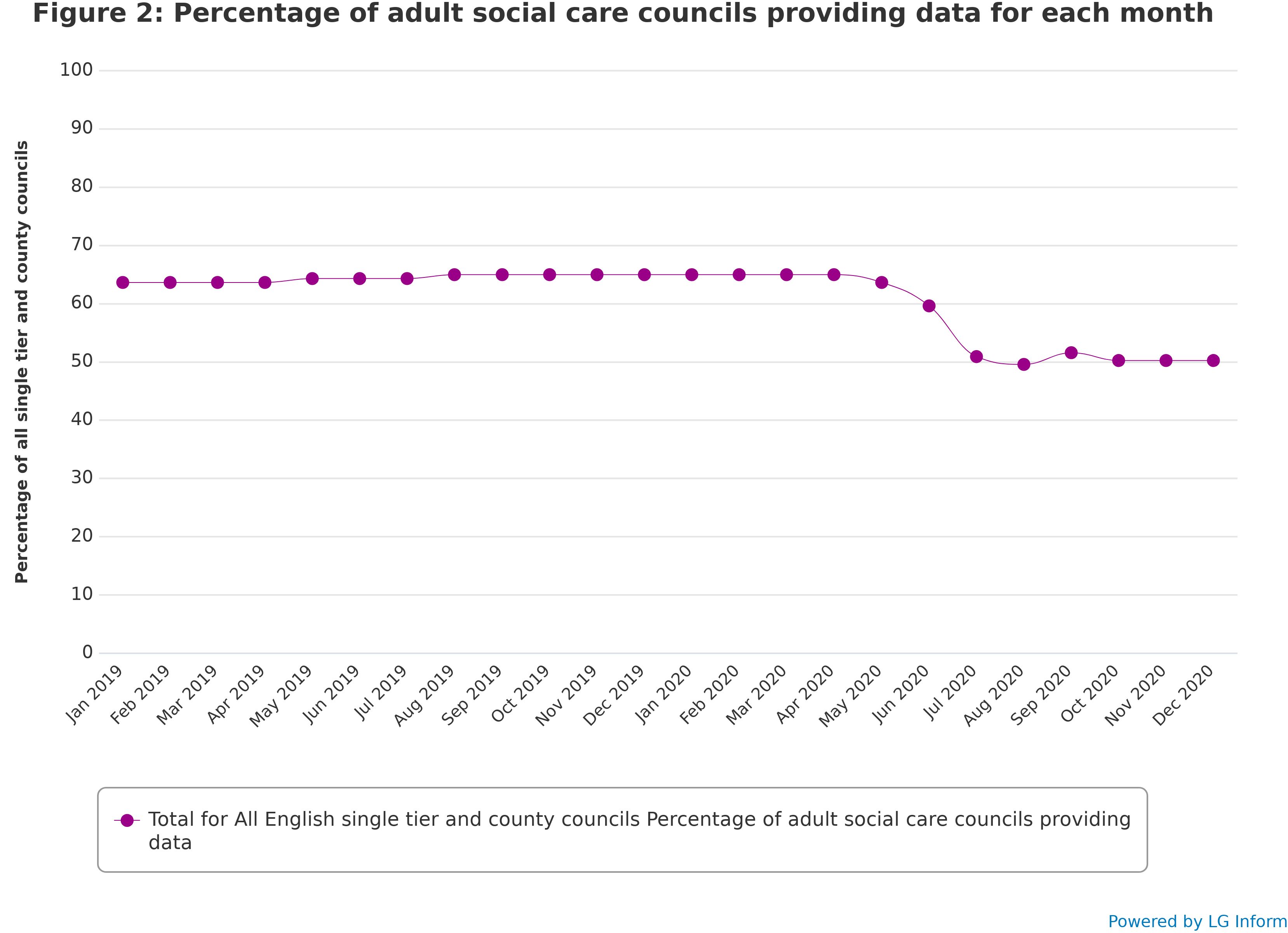

Although around 67 per cent of applicable councils have provided data for at least part of the period from January 2019 to December 2020, not all of these have provided data covering the entire period. Figure 2 shows the change in percentage of applicable councils providing data for each month. It demonstrates that participation by month has declined from a stable level of around 65 per cent to a lower stable level of just over 50 per cent.

Methodology: qualitative insights

The quantitative data provided for this report has been extremely helpful in identifying national trends, giving the bigger, overall picture. The qualitative data offers different insights, whilst some councils may very well fall into the trajectory of the median declines and spikes described in the quantitative data, the qualitative data captures the narrative and experience which is far more specific, nuanced and contextual to a particular council area. The variability of experience was highly significant and captures the very individual ecosystem in which any council exists. Each council has its unique set of factors that determine any number of structural, operational partnerships, protocols, and procedures, as acknowledged in the first Insight Project report.

What was noteworthy within the qualitative data was the various strategies that councils employed to navigate within the pandemic which saw changing approaches, new ways of working, communicating differently, creating guidance, changing referral routes, creating pro-active and preventative approaches in early identification of issues as they arise, identifying issues specific to that council.

Participants had the opportunity to provide qualitative data describing insights to targeted questions and sharing examples to illustrate their responses to the pandemic, changing landscapes in a separate section/chapter. 31 councils provided a narrative addressing the questions, representing 31 per cent of responding councils and 21 per cent of all councils in England. Their qualitative insights varied considerably as councils responded differently to any one question and not necessarily to all the questions.

Consequently, it was challenging to make broad conclusions or even direct comparisons between local authorities, due to the variety of information offered. There was great diversity in the depth and breadth of intelligence sent; some provided in-depth information, detailing trends in individual abuse types, conversion rates, sharing of trends in concerns and/or safeguarding enquiries. The outcomes of safeguarding enquiries were mentioned less frequently and textual information on location of abuse was variable. These insights are summarised in the different sections of the report.

About the report

Individual council data is treated confidentially in this project: this report does not identify any specific individual or council, instead showing the overall picture of the situation. Identifiable information about individual councils and respondents is used internally by the LGA but is only held and processed in accordance with the LGA privacy statement. Councils were asked if they could be named in the case studies.

Caveats

The pandemic and its impact varied across different parts of the country. The sample of councils participating in this project, whilst of significant size, is self-selected and therefore may not be fully representative. However, enough councils have participated to provide a broad picture and provided rich and valuable data of what has been happening in England regarding safeguarding activity during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In terms of the numerical data, it should be noted that data collected from April 2020 will not necessarily be validated, so there may be potential discrepancies to the validated figures submitted to NHS Digital. Further there have been some inconsistencies in the ways in which safeguarding concerns, safeguarding enquiries and other enquiries have been reported and work has been done to address this (recommended resources include: Making decisions on the duty to carry out Safeguarding Adults enquiries and Understanding what constitutes a safeguarding concern and how to support effective outcomes), which has been supported by the adult safeguarding workstream of the CHIP. Some participants in the first phase of the project commented that practice has improved between 2019 and 2020.

Structure of the report

Following an executive summary, each section in this report includes a narrative from the insights provided by respondents, where relevant, with specific themes that emerged from the findings.

These are followed by a summary of the numerical (quantitative) findings from the participating councils. The report describes the findings regarding safeguarding concerns and enquiries, types of abuser, location of abuse, location and types, and outcome of enquiries.

The report then discusses some further themes arising from the qualitative responses to the questions, focusing on areas relevant to the pandemic:

- COVID-19 related issues

- impact on safeguarding in regulated services including care homes

- carers and safeguarding

- changes to ways of working impacting on safeguarding practice.

Finally, the conclusion summarises some key messages following feedback regarding possible next steps.

Executive summary

The following gives an overview of the finding of the report. These findings are provided in more detail in each of the following sections.

Part 1: Safeguarding concerns

The general picture in England shows a sharp decline in the rate of safeguarding concerns in March and April 2020, only to increase steeply in May, June and July 2020, where it remained at a high level before decreasing during December 2020, following the second lockdown. Rates of safeguarding concerns were overall higher than in the previous year. Some councils reported increased numbers of concerns reported from emergency services, family, friends, neighbours, volunteers, and health partners. Councils reported receiving a high level of safeguarding concerns regarding adults who did not have care and support needs, nevertheless they were at risk of multiple categories of abuse and neglect and they were supported without going down a safeguarding pathway.

Part 2: Section 42 safeguarding enquiries

The trend of Section 42 safeguarding enquiries showed a similar pattern, with a steady decrease in rates from January to April 2020 before increasing again to almost exactly the pre-pandemic level, then falling off and decreasing sharply by December 2020. Overall, the pattern in the rate of safeguarding enquiries looks like one and a half iterations of a ‘v-shaped recovery’. The data, however, does not convey the increased complexity of enquiries and challenges in how safeguarding activity was undertaken as evidenced in the responses from councils.

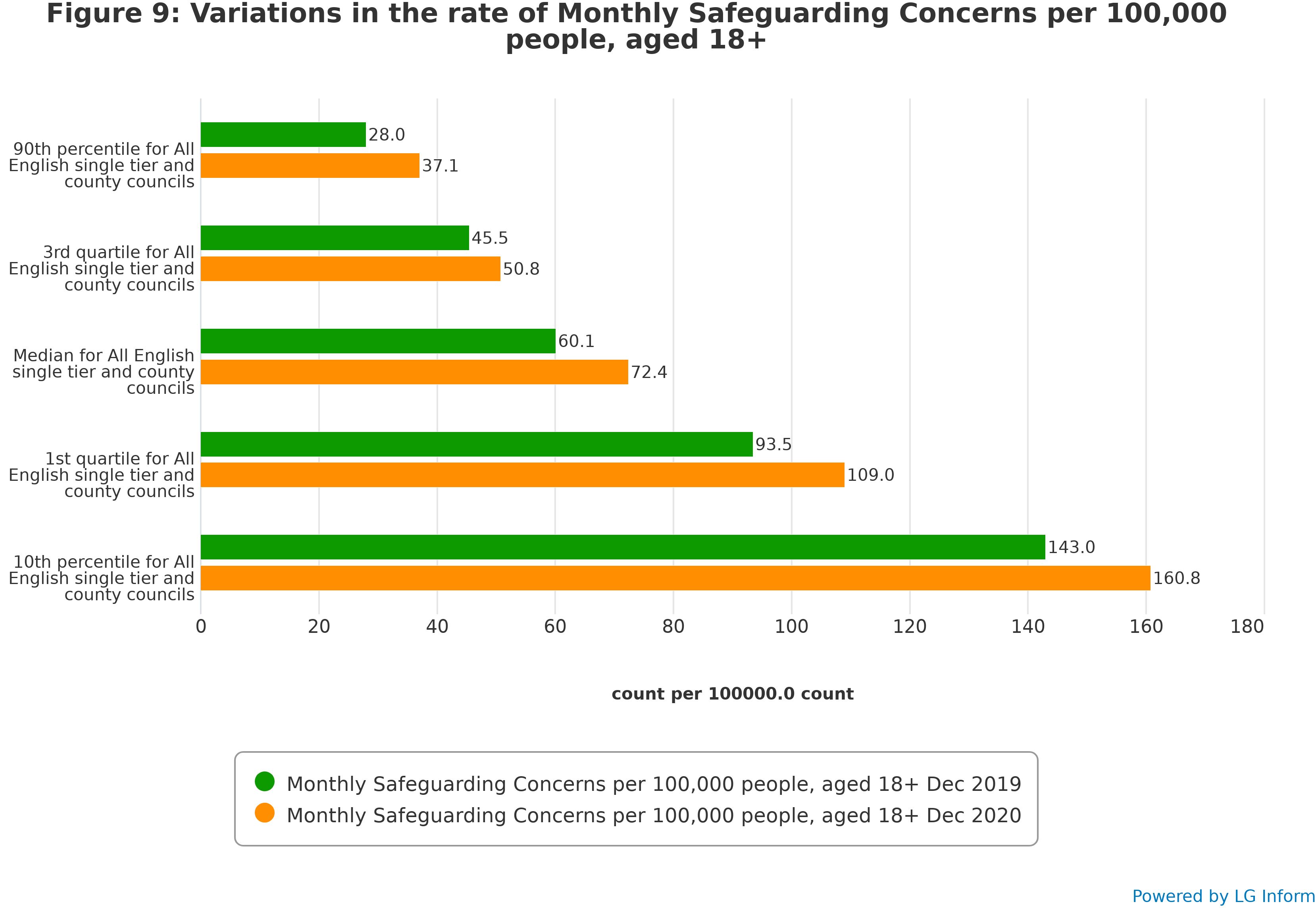

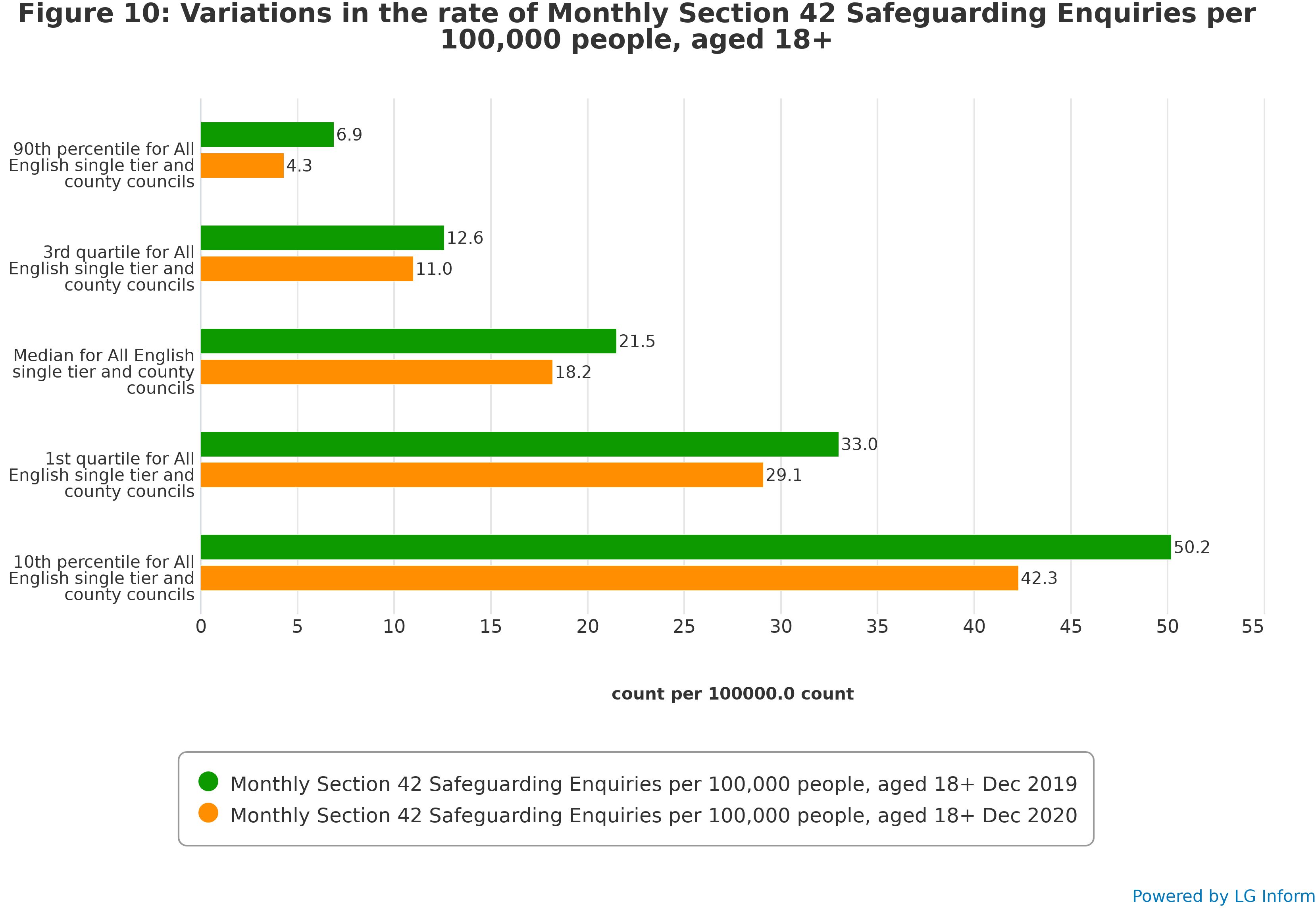

Part 3: Understanding variation between councils

The overall picture shows the rate of safeguarding concerns in December 2020 was higher than that of December 2019, although considerable variation between councils remains and points to a wide range of different situations experienced by different councils. There was considerable variation between individual councils regarding the rate of Section 42 safeguarding enquiries, although the December 2020 rate was lower than the December 2019 rate. This section demonstrates how COVID-19 and lockdown has, impacted councils unevenly across England in their safeguarding activity. Experiences are localised and specific to that locality.

Part 4: Breakdown by type of abuse

The percentage distribution of types of abuse and neglect in safeguarding enquiries remained relatively constant throughout 2019 and 2020, but with moderate increases in, domestic abuse, self-neglect, and psychological abuse in 2020 compared with 2019. Councils commented on the impact of the pandemic and lockdowns on: the incidence of domestic abuse; the identification of self-neglect through outreach to clinically vulnerable residents; new COVID-related scams; on mental health needs (related to self-neglect) and opportunities to work with people who were street homeless.

Part 5: Breakdown by location of abuse

Safeguarding enquiries where the risk is in the person’s home increased noticeably during the lockdown period. The data evidences an overall decrease in safeguarding enquiries in both nursing and residential home settings during the pandemic period, with peaks in safeguarding enquiries completed in June and November 2020 regarding residential care settings. Councils commented on reduced access by professionals, families, and friends to care homes and concerns were that there would be a ‘surge’ following the easing of the lockdowns, which is reflected in the data.

Part 6: Breakdown by type and location of abuse

Analysing data by type of abuse and location of risk experienced shows that there were marked increases between 2019/20 and the first half of 2020/21 in psychological abuse, neglect and domestic abuse located in an individual’s own home and neglect located in a residential care home. These findings from the NHS Digital mid-year data collection are consistent with the findings of the data from Insight Project returns.

Part 7: Breakdown by outcome of enquiry

The outcomes of enquiries remained relatively unchanged throughout 2019 and 2020, although there was some indication that the proportion of enquiries with outcome of “Risk Reduced” increased in the latter half of 2020, at the expense of “Risk Removed”.

Part 8: Themes around safeguarding in a pandemic

Councils commented on safeguarding risks connected to the COVID-19 pandemic. They described challenges regarding supporting people living in care homes and the multi-disciplinary work undertaken to reduce the risks (including safeguarding risks) for residents. Councils also commented on the impact of the pandemic and lockdown on ways of working, particularly the reduction in face-to- face contact and the consequences for safeguarding activity. They described the pros and cons on using IT and video conferencing, and the learning from their experiences. There are two short case studies from contributing councils to illustrate the level of detail participants provided describing local responses to the challenges being faced.

Part 9: Consultation on the future of the Insight Project

The results of a short survey to gather views on whether to continue the project with another round of data collection are summarised. Most of the respondents said that they would support continued data collection covering the period from January to June 2021.

Part 10: Conclusion

The report concludes with an overall summary of the findings and their implications for adult safeguarding in the local government sector.

Part 1: Safeguarding concerns

Insights regarding safeguarding concerns 2020

The COVID-19 pandemic and lockdowns had an impact on the patterns of safeguarding concerns reported to councils from March 2020 until December 2020. Whilst the quantitative data captures the median levels of safeguarding concerns fluctuations faced by councils in England (see figures 3 to 5 and Figure 9), the qualitative data captures the narrative behind those councils who fit neatly into the median, but also those who do not. Most councils experienced some change in patterns of safeguarding concerns following the start of the pandemic in 2020 from the previous year, only 29 per cent of councils who provided qualitative data said they experienced no change. There was a considerable variation of experiences – some areas saw very slight increases in numbers of safeguarding concerns whilst others experienced more extreme changes in patterns of behaviour from referrers. Some councils experienced very high levels of referrals, as high as a 400 per cent increase.

Half of the councils who answered the question regarding changes in patterns of safeguarding concerns saw an overall increase in safeguarding concerns following the start of the COVID-19 pandemic from a range of referrers. 29 per cent of councils saw an increase from emergency services, 29 per cent saw an increase in referrals from family, friends, neighbours, and volunteers and 14 per cent saw increased referrals from health partners.

Some of the highest levels of safeguarding referrals came from emergency services and volunteers who were taking part in providing COVID-19 related support during the lockdown periods. Neighbours, the ‘general public’ and volunteers tended to be raising safeguarding concerns because they were supporting people through the pandemic and were coming face-to-face with adults who may appear to be experiencing abuse and neglect, particularly regarding self-neglect hoarding and residents living in ‘squalid’ conditions.

Some adults who were subject to safeguarding concerns did have care and support needs and went through the safeguarding enquiry process, but the majority appear to be adults without care and support needs or required signposting and/or preventative support instead. The councils commenting on emergency services as an increased source of referral, mentioned that many of these concerns did not meet Section 42 criteria for safeguarding enquiries. Councils reported receiving a high level of safeguarding concerns regarding adults who did not have care and support needs but were at risk of multiple categories of abuse and neglect and these were supported without going down a safeguarding pathway.

Councils saw both increases and decreases in referrals regarding safeguarding concerns from family and friends (there was evidence from qualitative commentary that this was very much dependant on how these anxieties were reported). Family and friends expressed concerns about being unable to visit their relatives or friends in care homes; physical deterioration of the person when they were able to visit them; staffing levels in the homes; and regarding the correct use of personal protection equipment by staff.

Some councils described an increase in the number of concerns from health professionals over the duration of the pandemic, as high as 40 per cent in one council. Safeguarding concerns from health partners were noted as being noticeably low during lockdown periods but increased after lockdowns eased.

Patterns in safeguarding concerns data

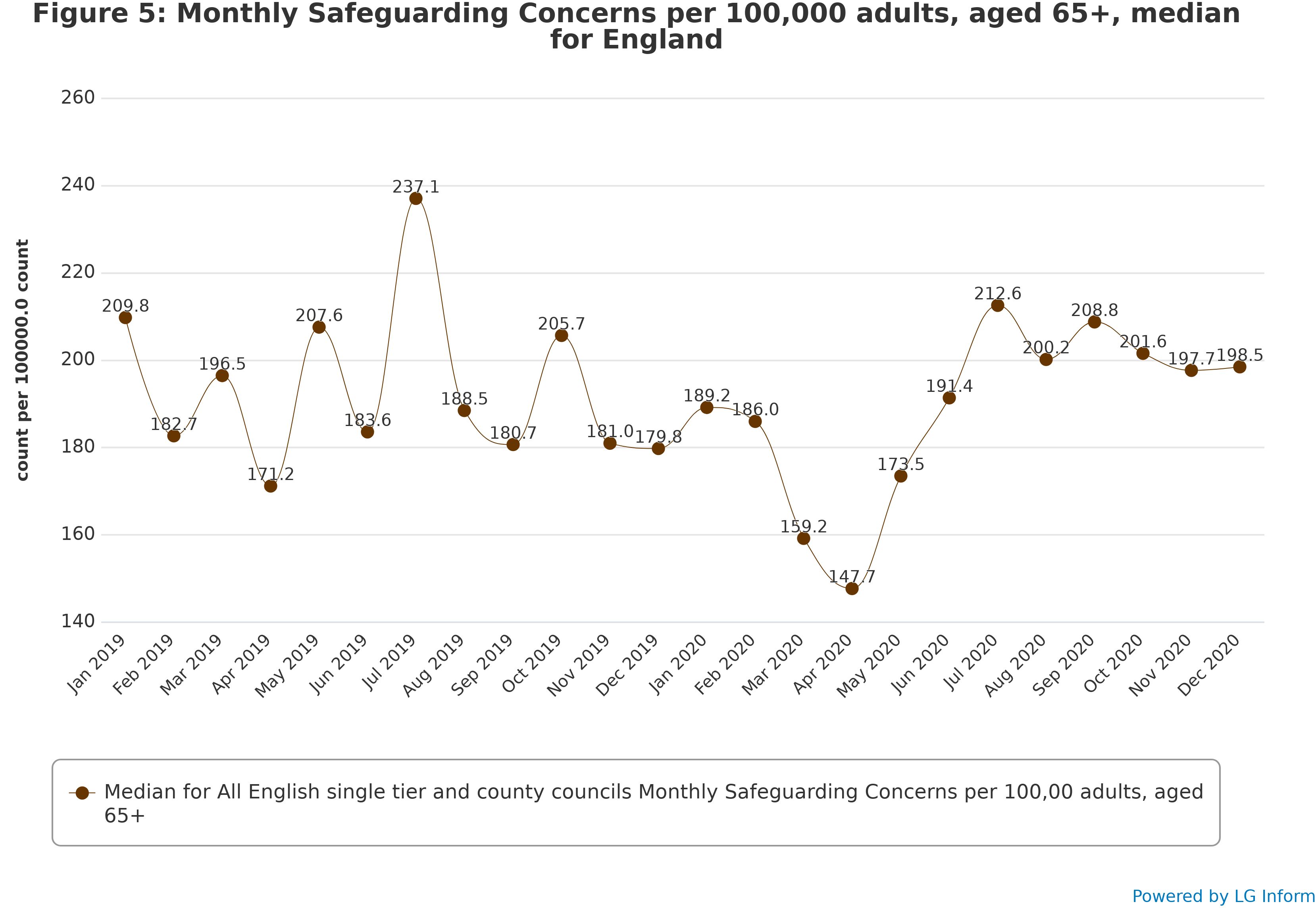

The overall rate of safeguarding concerns declined sharply in March and April 2020, only to increase steeply in May, June, and July, where they remained at a high level before decreasing towards December. Among 18-64-year olds these patterns tended to be exaggerated, whereas among those aged 65 and over changes in the rate of concerns were less considerable over the time period and did not feature a decrease in December 2020.

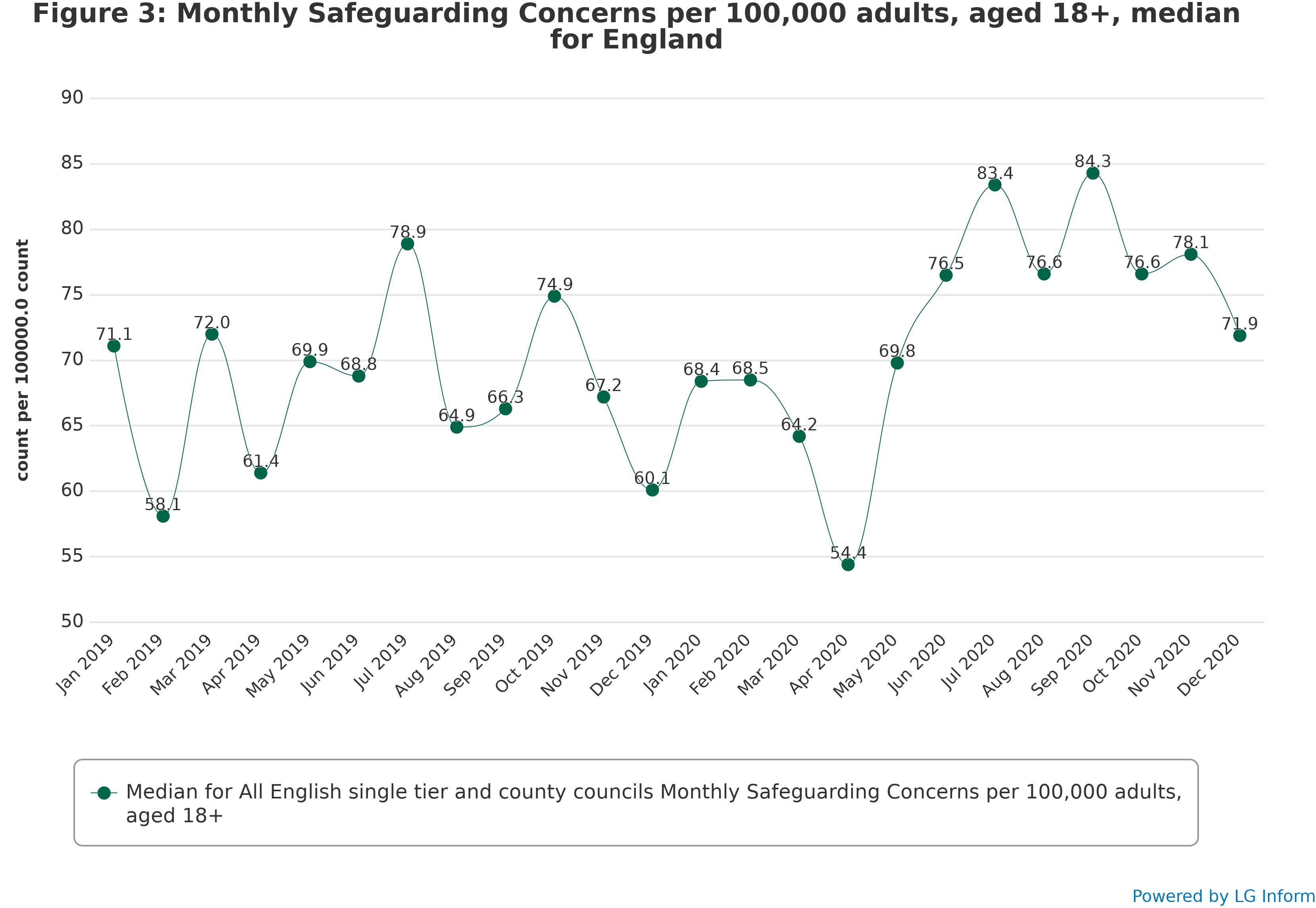

As Figure 3 shows, the rate of safeguarding concerns per 100,000 people aged 18 and over fluctuated considerably even in advance of the pandemic, generally around an average level of about 65. The rate decreased to around 56 per 100,000 people in April 2020, lower than the April 2019 level of around 61 per 100,000 people. The April 2020 rate is the lowest recorded in 2019 or 2020. This rate steadily and rapidly increased to around 83 per 100,000 people by July 2020, higher than the rate of 79 per 100,000 people in July 2019. Whilst 2019 also shows a pattern of a decrease in the rate of safeguarding concerns in April followed by an upsurge leading into July, in 2020 this trend was considerably clearer and sharper.

After July 2020, the rate of safeguarding concerns fluctuated around an average of around 80, noticeably higher than the average at the same time in the previous year. In December 2020 the rate of concerns decreased again to around 72, although this was still considerably higher than the rate of around 60 in December 2019.

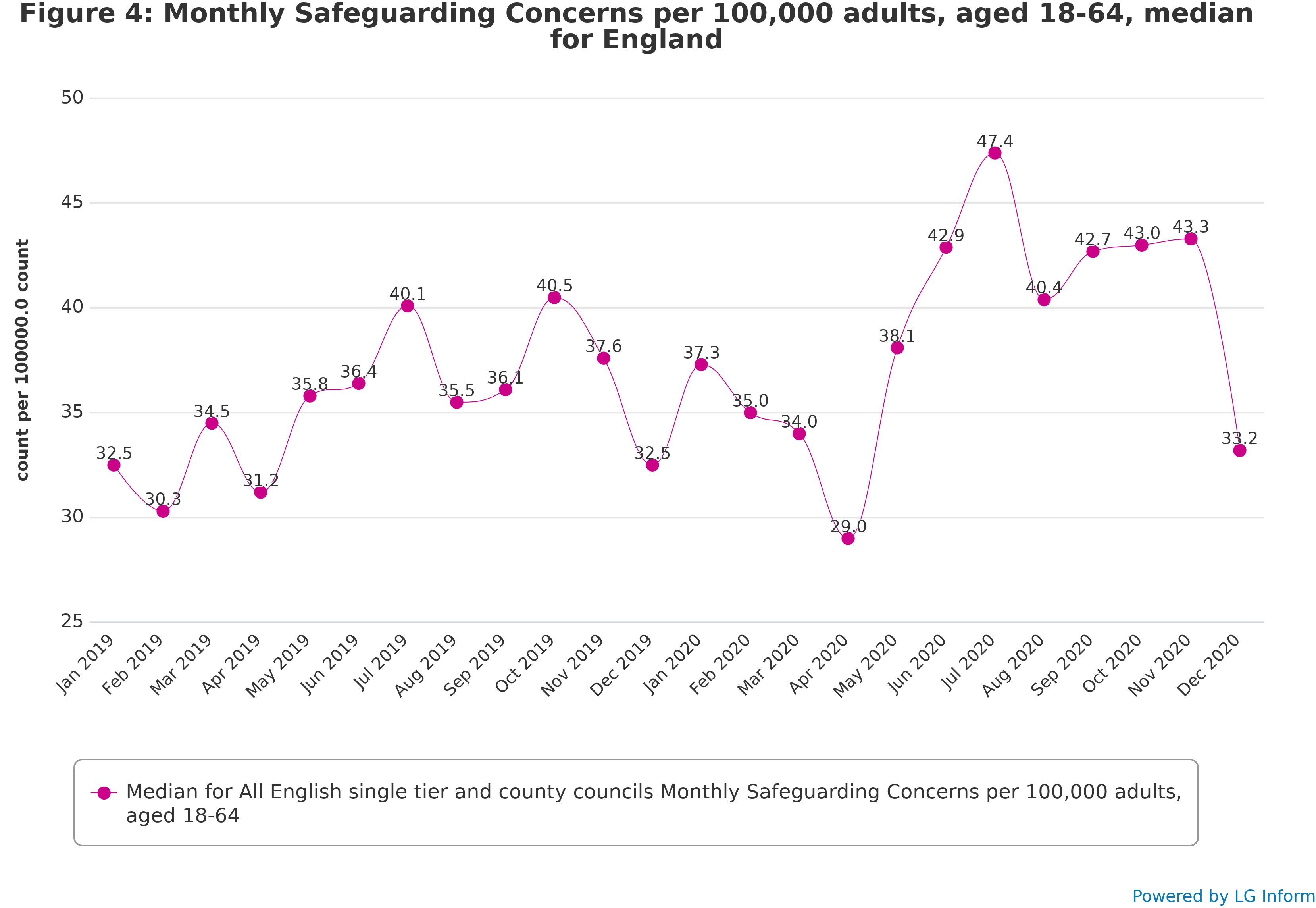

When considering the rate of concerns for 18-64-year olds per adult aged 18-64, the picture is overall similar to that for all adults, but with sharper fluctuations since the start of the pandemic in England. Figure 4 shows that the pre-pandemic rate of concerns among 18-64-year olds was around 35, and that this tended to fluctuate less steeply than the rate for all adults. The decline in April 2020 reduced this rate to around 29, though this was not much lower than the April 2019 rate of around 31. The May to July 2020 upsurge among 18-64-year olds was even steeper than that for all adults, increasing the rate of safeguarding concerns to around 47 per 100,000 adults. The rate in August to November 2020 remained very stable at around 42 per cent, but the decline in the rate of safeguarding concerns in December 2020 was steeper than for all adults, dropping back down to around 33 per 100,000 18-64-year olds. This, however, was almost identical to the rate of concerns in December 2019, so may represent a return to a “normal” rate of concerns rather than an unusually low rate.

In contrast to the rate for 18-64 year olds, the rate of safeguarding concerns for adults aged 65 and over per person aged 65 and over in the population tended to fluctuate more sharply before the COVID-19 pandemic, and has since become more stable. In contrast to the rates for all adults and 18-64-year olds, the highest rate of concerns in the period among those aged 65 and over was before the pandemic, in July 2019, at around 237. The rate of concerns decreased steadily from February to April 2020 to around 150 – lower than the April 2019 rate of 170. The subsequent upturn in the rate of concerns per older person was less steep than among 18-64-year olds, bringing the rate to around 215 in July 2020 – considerably lower than the rate in July 2019. After this, the rate of concerns among older adults remained stable at around 210, and did not decline in December 2020, unlike the rate of concerns for 18-64-year olds.

Part 2: Section 42 safeguarding enquiries

Insights regarding safeguarding enquiries 2020

As with safeguarding concerns, the rates of safeguarding enquiries were affected by the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdowns (see Figures 6 to 8 and Figure 10). The data, however, does not convey the substance or complexity of the safeguarding activity provided by the qualitative insights from councils. These have been described under the themes of complexity and process.

Complexity

Growing complexity of safeguarding adults work was noted as a significant issue amongst most councils, 77 per cent of responding councils stated that they had evidence of growing complexity of casework. Complexity included the way that abuse or neglect presented itself within adults’ lives, the process of conducting an enquiry remotely, lack of access to the person with care and support needs when carrying out a safeguarding enquiry, inability to disclose due to potential perpetrators, cause of risk or discrete access to report, and the number of people who may not have care and support needs but were at still at risk of abuse and neglect.

Councils reported that complexity in safeguarding casework grew from adults no longer having access to informal and formal support due to COVID-19 restrictions and multiple, complex, and sometimes more acute needs arising. Specific examples of factors contributing to complexity included: conducting the enquiry process within pandemic conditions; domestic abuse; forced marriage; mental health; dementia; financial abuse; drug and alcohol misuse; isolated deaths in care homes; complex dynamics between carer stress versus carer neglect; hidden harms; modern slavery; increased concerns around the inappropriate use of Do Not Attempt cardiopulmonary resuscitation (DNACPR) orders; removal of a resident from a care home who was subject to Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards; missing and absconded individuals and whistle blowing.

Safeguarding enquiry process

Councils reported that complexity in safeguarding activity arose from the challenges that social distancing brought to the Section 42 enquiry process. This often meant being unable to undertake essential face-to-face visits; the practicalities in progressing enquiries had become more difficult. Limitations of face-to-face contact led to an increased reliance on second-hand information. This meant that it was challenging for practitioners to carry out person-centred safeguarding during the pandemic, which professionals have tried to mitigate through conducting enquiries virtually and over the phone to achieve the outcomes the people would like to achieve. Prior to the pandemic conditions, practitioners would be able to gauge the risks for the adult and the situation in person. The changed way of working resulted in the enquiry process taking longer and practitioners being unable to ascertain a complete picture, unable to obtain as full level of case detail as was the case before the pandemic.

Councils described how frontline practitioners were having to monitor cases remotely, relying on other professionals or colleagues. Some councils expressed reduced opportunities for contacts between practitioners, which decreased opportunities for identifying possible safeguarding concerns or issues. There were reduced opportunities for operational staff to speak to each other– there was difficultly of staff communicating with care home and hospital staff whilst working within pandemic conditions, which made it difficult to get the information required in a timely way. For some remote working increased the possibility that safeguarding teams were not being made aware of safeguarding concerns and soft intelligence is not shared in a timely way.

Additionally, because of reduced face-to-face assessments taking place, practitioners acknowledged that there were less opportunities for people to make safeguarding disclosures. There were concerns that the adult may face barriers to disclosing abuse or issues in their residence if a potential abuser, cause of risk or resident employees in the room whilst speaking virtually with practitioners. There were some very noteworthy observations made about the increase in people stating that they did not wish to proceed with safeguarding enquiries where there was alleged abuse from family members. It was suggested that this may have been because people were more willing to put up with abuse in exchange for social contact during a period where social contact was less available and more valued.

Several councils also mentioned that Section 42 activity process was further complicated because of delays: delays in organising safeguarding meetings and delays in completing agreed actions and completing safeguarding enquiries. When these delays related to safeguarding enquiries in care homes, this was due to multiple pressures that care homes were facing.

Conversely, the early response to supporting “vulnerable” adults in the community when the first lockdown began had the consequence of identifying more people who were experiencing self-neglect and hoarding at an earlier stage due to active contact with adults as part of the COVID-19 outreach work.

See Part 8 for further discussion of the operational challenges for front line safeguarding services and the mitigations put in place as well as the benefits of new ways of working.

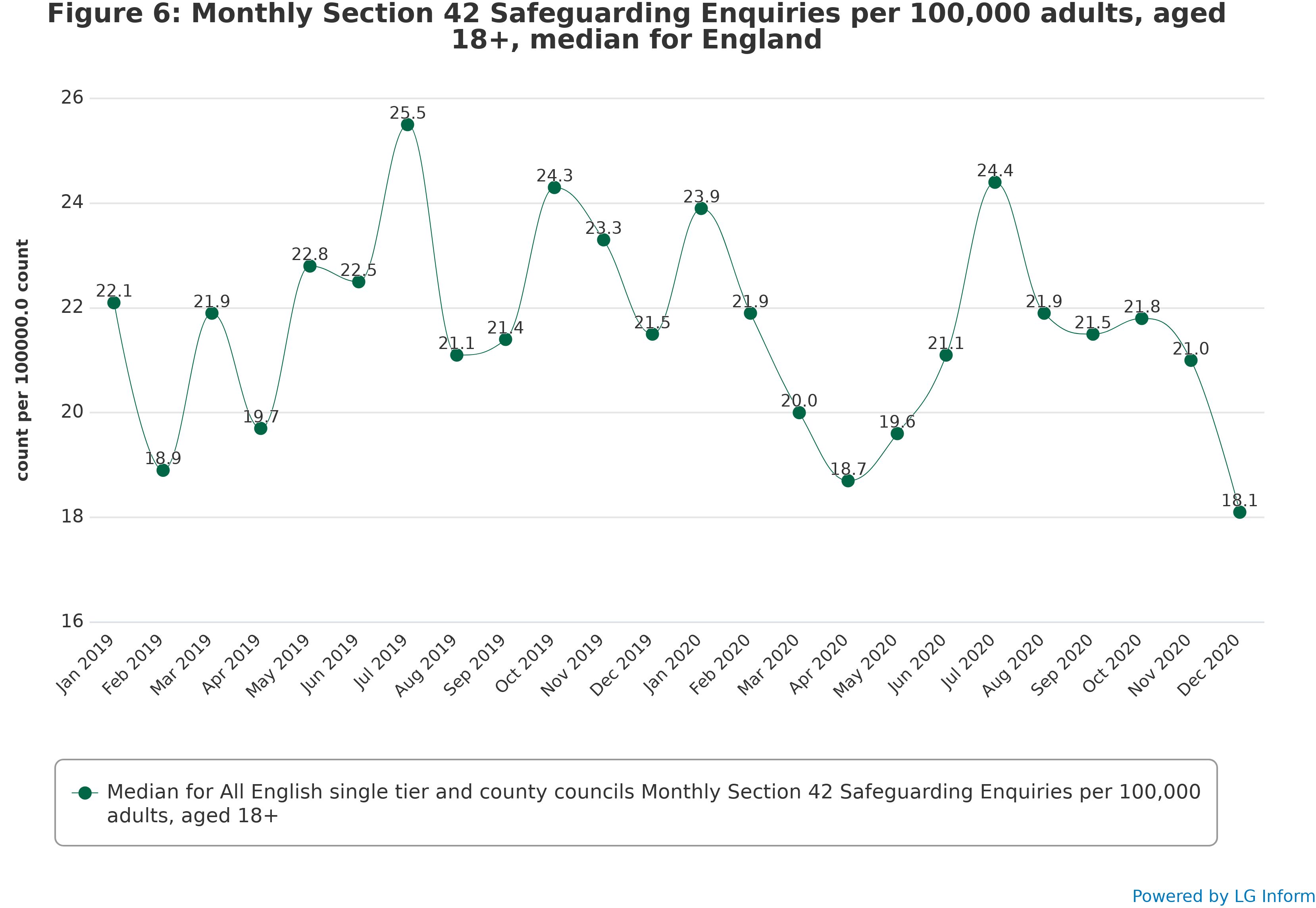

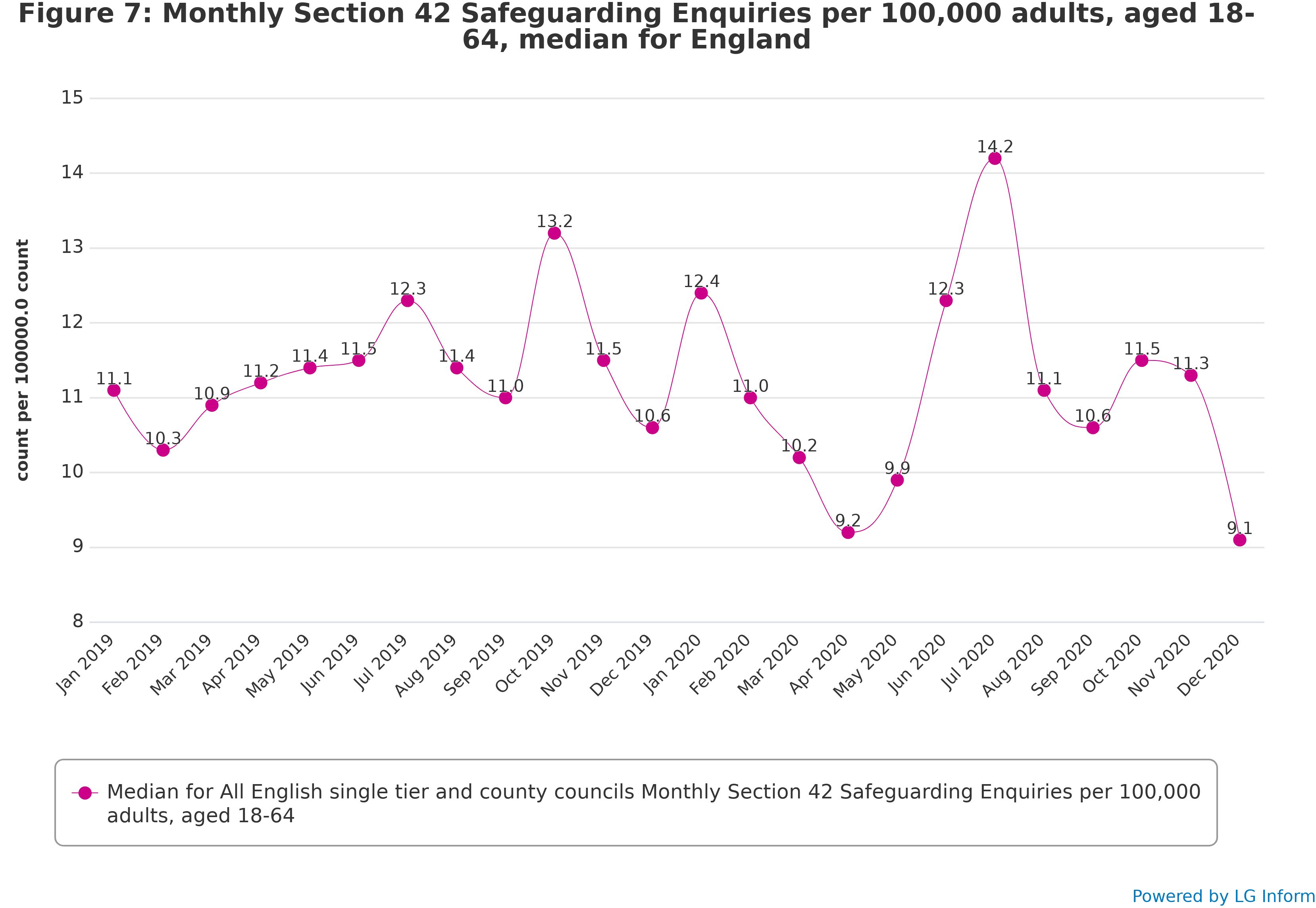

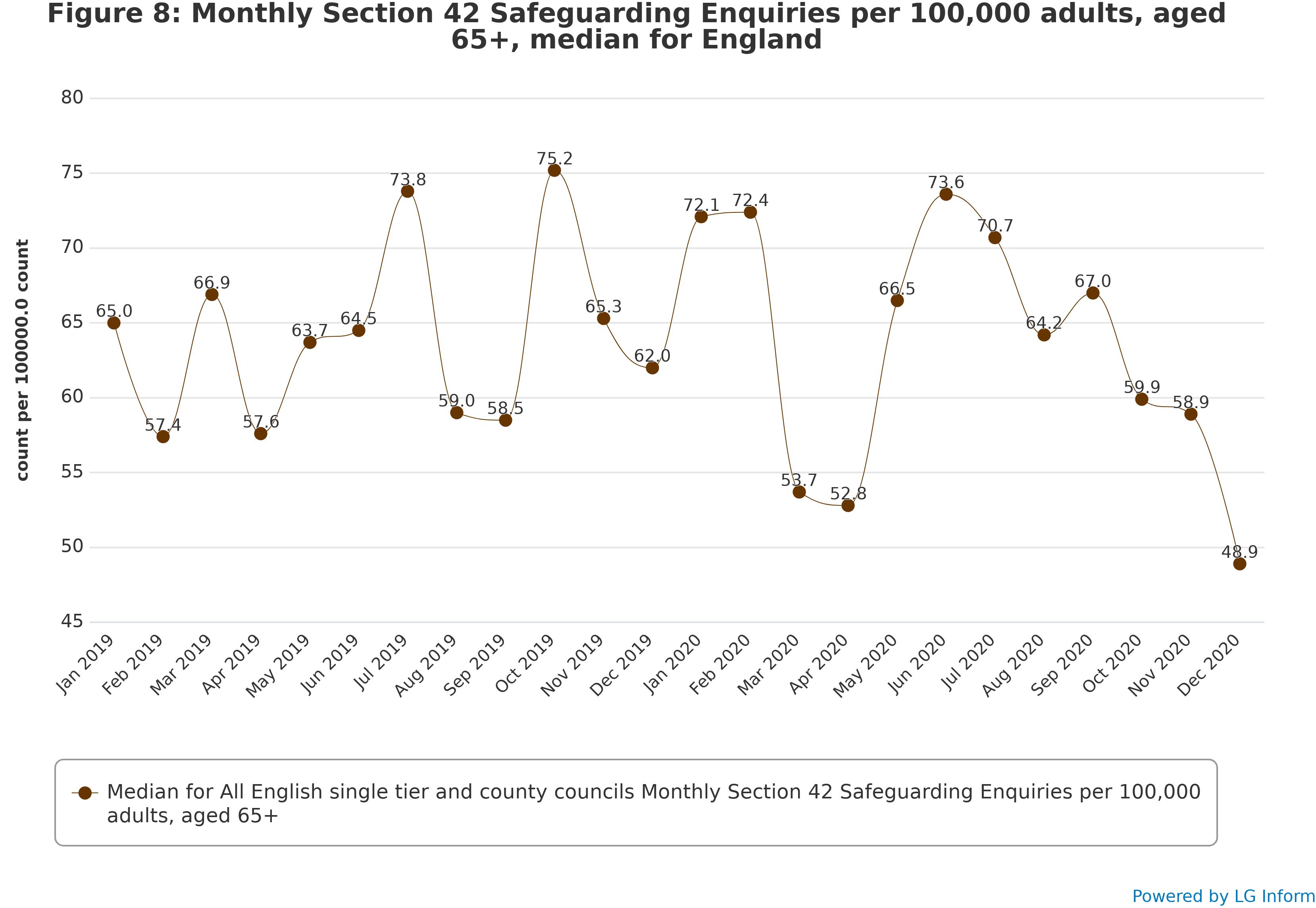

Patterns in safeguarding enquiries data

The rate of Section 42 enquiries for all adults decreased steadily from January to April 2020 before increasing again to almost exactly the pre-pandemic level, then falling off and decreasing sharply by December 2020. This pattern was roughly the same between age groups, with the July 2020 upturn in the rate of enquiries being strongest among 18-64-year olds, but with few other considerable differences between working-age adults and older people. Overall, the pattern in the rate of Section 42 enquiries on record looks like one and a half iterations of a “v-shaped recovery.”

Pre-pandemic, the rate of Section 42 enquiries per 100,000 people aged 18 and over fluctuated around an average of about 22. This decreased steadily between January and April 2020, although the rate of around 19 in April 2020 was not considerably lower than the lowest rates in the period before the pandemic and was only a little lower than the rate of around 20 in April 2019. The decrease was followed by an almost exactly equal increase in the rate of enquiries between April and July 2020, bringing the rate up to around 24. This rate of enquiries was, however, lower than the rate of 25 in July 2019. In August to November 2020 the rate of enquiries dropped again, remaining fairly constant at just under 22, before, as with the rate of concerns, dropping markedly to around 18 in December 2020. This is the lowest rate of Section 42 enquiries in the time, though not by a wide margin.

Among 18-64-year olds, the rate of Section 42 enquiries remained relatively stable at around 11 in the first half of 2019, before starting to fluctuate in a way that increased at the start of the pandemic. The rate dropped to around 9 in April 2020 before climbing to around 14 in July 2020, the highest rate during the two-year period. The rate then dropped sharply again, almost exactly to the same extent as during the original lockdown, once again reaching a rate of around 9 in December 2020.

Among older people, the rate of Section 42 enquiries appears to have been fluctuating sharply month on month for the entirety of the period measured. The rate was brought down to around 53 in March and April 2020, increasing to a high but not atypical 75 in July 2020. As with working-age adults, the rate of enquiries has since declined sharply, ending at around 50 in December 2020.

Part 4: Breakdown by type of abuse

Insights regarding the nature of abuse and neglect

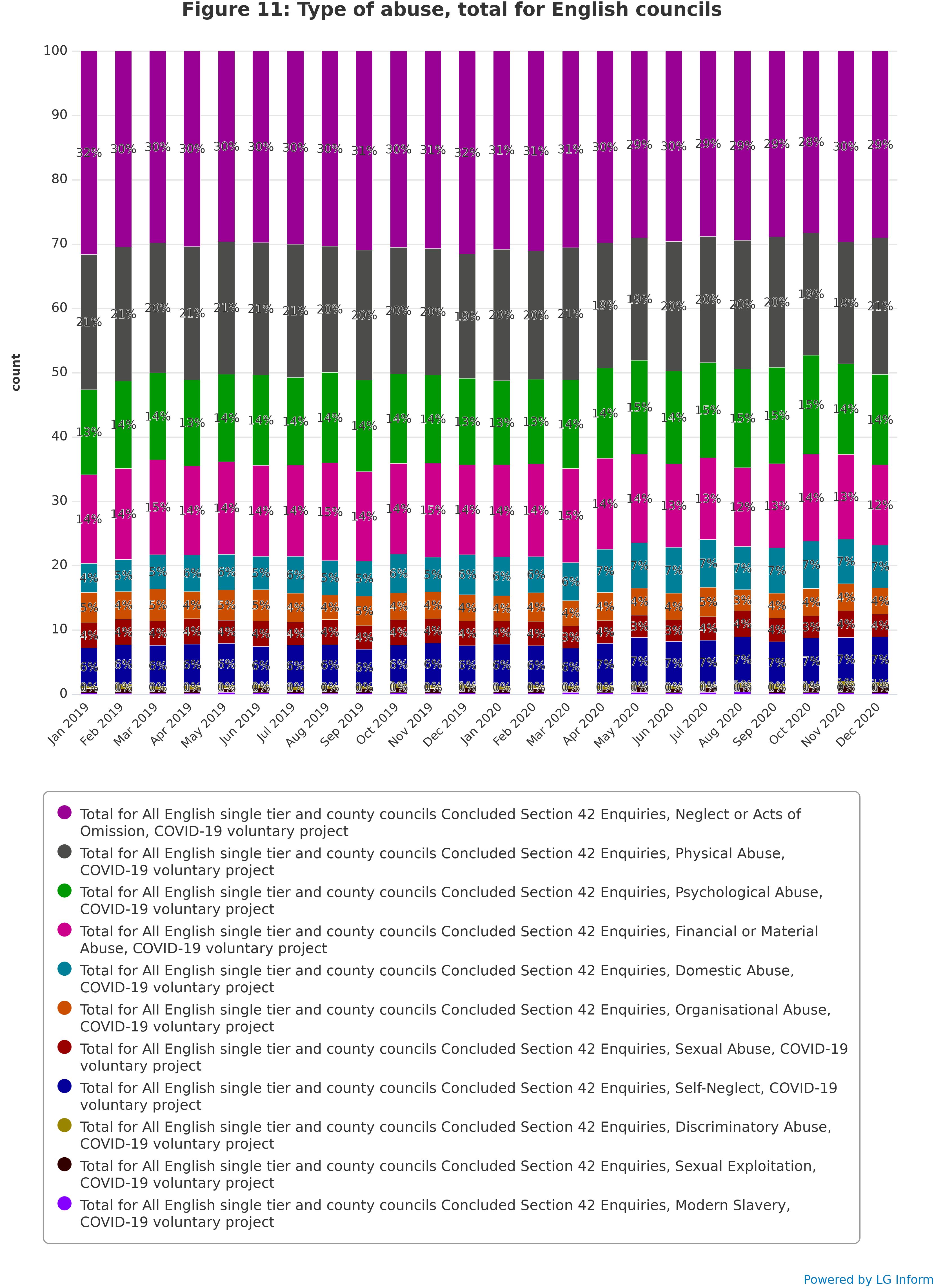

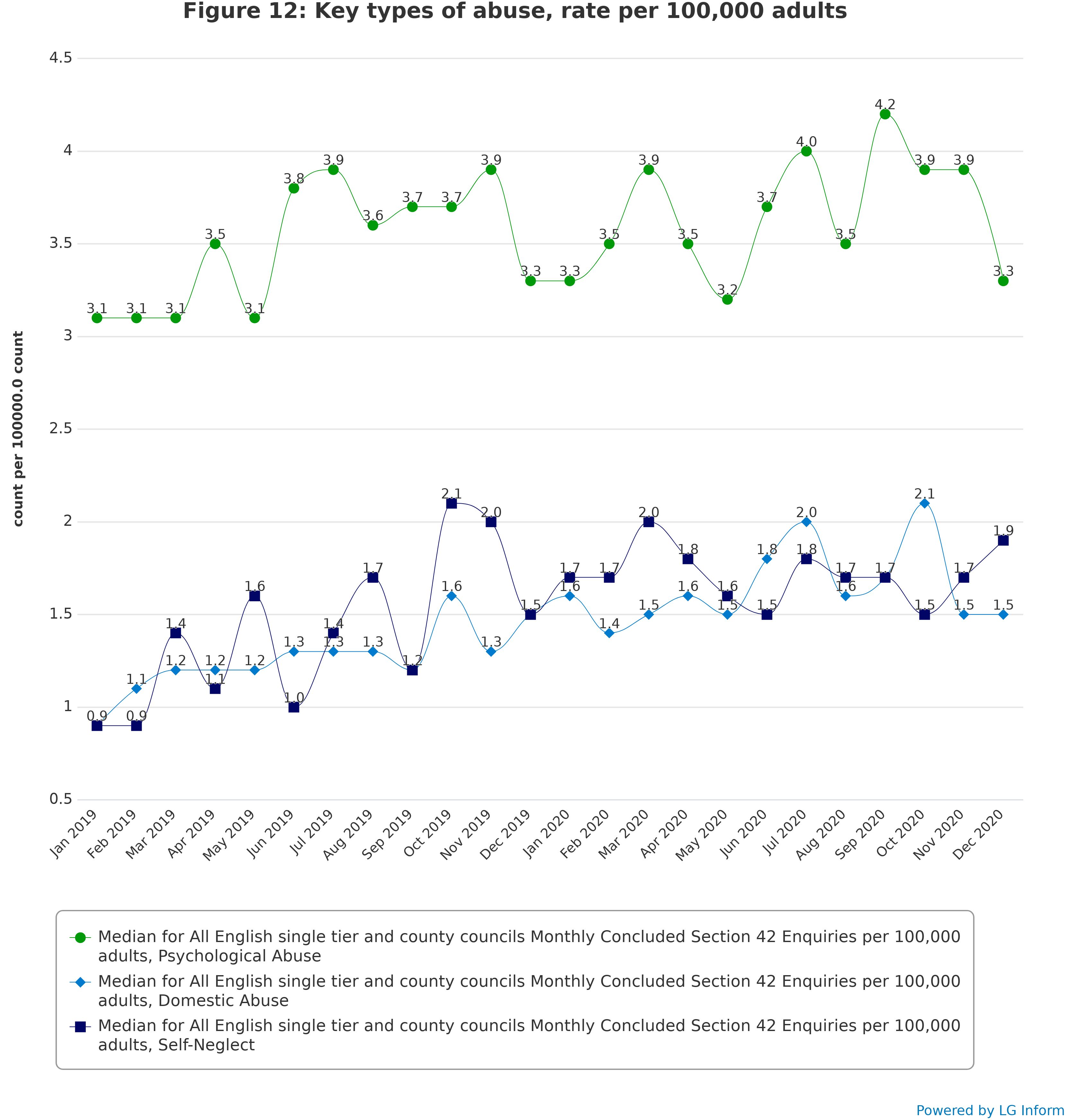

The data categorises the type of abuse and neglect and the changing patterns are described below (see Figures 11 and 12). Councils provided narratives both regarding these reported types of abuse and themes and issues which do not fit into the categories. Their observations are summarised under the following themes: domestic abuse; self-neglect; homelessness; financial abuse; mental health; and mental capacity.

Domestic abuse

Domestic abuse proved a complicated picture; some councils saw increased levels of domestic abuse; some saw no change and others were unable to confirm. There was some identification as to the nature of some of the domestic abuse, which included financial abuse, ‘best interest’ decisions and family disputes. Some identified higher risk profile of domestic abuse cases, which were subject to escalation. For those councils who mentioned increased levels of reporting of domestic abuse some attributed this to increased police referrals. For some councils there was a direct correlation between lockdown period and increases in domestic abuse, this included safeguarding concerns reported about survivors of domestic abuse who did not have care and support needs.

Safeguarding teams expressed how, with the pandemic conditions, an adult at risk of domestic abuse was more likely to be living in close proximity to the perpetrator and unable to speak freely and so teams were finding it difficult to identify safe ways to access and communicate with a survivor of domestic abuse. Depending on location, some areas were able to offer continued face-to face contact for those experiencing domestic abuse whilst others were less able to offer this and did so only when there were high levels of risk.

Councils described measures they put in place to respond to domestic abuse of people with care and support needs during the pandemic. Safeguarding teams worked in partnership with Domestic Abuse Partnership Boards or dedicated domestic abuse providers to take a more targeted approach to supporting survivors. One council mentioned working with the police and having dedicated opening hours and weekly online sessions for people experiencing domestic abuse. This council also mentioned higher levels of online engagement with perpetrators of domestic abuse.

Self-neglect

There were two dominant narratives about self-neglect. The first narrative concerned the early identification by volunteers of ‘clinically extremely vulnerable’ people that they were supporting. Some people had care and support needs and were known to adult social care services, others either did not care and support needs but were at risk of abuse or neglect or they were not considered to have been at risk of abuse or neglect. The second predominant narrative was the increasing difficulties that practitioners were experiencing in getting people who were self-neglecting to engage with them during the pandemic; the pandemic was given as an additional reason as to why people were unable to communicate with professionals. Health partners were reported as identifying increased numbers of patients who had been ‘hidden’ during lockdown and then presented with more acute self-neglect when they presented at the health setting following the easing of lockdown.

Homelessness

The Government’s initiative, ‘Everyone In’ charged local authorities with supporting people who were sleeping rough to move into self-contained accommodation. Many Councils described proactive work with people who presented as street homeless where they were able to accommodate them during the pandemic. This provided councils a good opportunity not only to house people who were experiencing homelessness but also to develop and/or strengthen engagement with people who may have been less inclined to engage with statutory services, who had safeguarding needs. This resulted in a rise in referrals, particularly regarding mental health concerns and self-neglect. Councils also commented that increased demand on housing services created challenges for multi-agency working due to increased demands on frontline staff. There were additional challenges around some adult experiencing homelessness being unable or unwilling to follow Coronavirus restrictions and this being perceived as a potential safeguarding issue. Councils mentioned that this gave them an opportunity to work with partner agencies to be able to engage with people who were experiencing street homelessness, who may have previously not engaged with statutory agencies. One council shared an account of how they took this opportunity to engage further with individuals who were less inclined to engage, including cases people who were experiencing self-neglect.

Financial abuse

Whilst quantitative data showed broadly similar level of financial abuse over the period of the pandemic, councils’ comments that what had changed was the nature of abuse. They reported financial abuse centred around COVID-19 scams. A number of scams were identified, which included people impersonating ‘professionals’ to gain entry to an adult’s home to steal money and property. There were also scams reported concerning false charging for COVID-19 testing kits, cleaning, and COVID-19 vaccines.

Mental health

Councils noticed an increase of mental health issues during the pandemic; 47 per cent of responding councils saw an increase in the identification of mental health needs. This included increases in: the referring of concerns from mental health teams, emergency services, members of the public some of whom were volunteers responding to the pandemic; and also increases in safeguarding concerns passing through into mental health services, including people not known to services. 10 per cent (3/30) of councils who answered the question identified an increase of suicide in their locality. 33 per cent of councils (10/30) identified an increase of self-neglect whilst 10 per cent (3/30) councils mentioned increases in Mental Health Act Assessments. Other associated issues included: alcohol and drugs, anxiety, isolation, domestic abuse, adhering to COVID-19 lockdown restrictions and distress from people with dementia were identified as relevant to the mental health and safeguarding.

Almost half of councils (15/30) described increased volume of people experiencing mental health issues including self-harm, suicidal ideation or attempts, self-neglect, ‘mental health crisis’, ‘deteriorating mental health’ reflected in the identifying of increased levels of Mental Health Act Assessments.

The increased number of people experiencing mental illness included people not previously known to the local authority, suggesting onset of mental illness which could be attributable to the pandemic. Councils noted several people expressing difficulty coping with the pandemic and its impact.

Patterns in types of abuse

The percentage distribution of types of abuse and neglect in Section 42 enquiries remained relatively constant throughout 2019 and 2020, but with moderate increases in psychological abuse, domestic abuse, and self-neglect in 2020 compared with 2019.

The most prevalent type of abuse throughout the period, at around 30 per cent, was neglect or acts of omission. This was followed by physical abuse, at around 20 per cent, and psychological abuse, generally increasing from around 13 per cent in early 2019 to around 15 per cent in late 2020. Financial or material abuse accounted for a further 14 per cent.

Domestic abuse generally increased from around 4 per cent to around 7 per cent of Section 42 enquiries in this period. Similarly, self-neglect increased from around 6 per cent to around 7 per cent.

Figure 12 shows that the average rate of enquiries involving psychological abuse went from a low of 3.0 in February 2019 to a high of 4.2 in September 2020. The rates of enquiries involving domestic abuse and self-neglect also tended to increase modestly in this period, both increasing from a rate of under 1 to a rate of around 1.5.

Part 5: Breakdown by location of abuse

Insight regarding location of abuse

During the pandemic there were concerns about the impact of the lockdown on care homes and reduced access by professionals, families, and friends. There were concerns that there would be a ‘surge’ following the easing of the lockdown. The quantitative data suggests that abuse and neglect in residential and nursing settings were either unidentified or were identified later due to COVID-19 restrictions, especially regarding adults who were known to adult social care. One council drew a link between late identification of safeguarding concerns and an escalation in organisational abuse. Further insight into these concerns and the action taken to mitigate risks, are explored in Part 8 of the report.

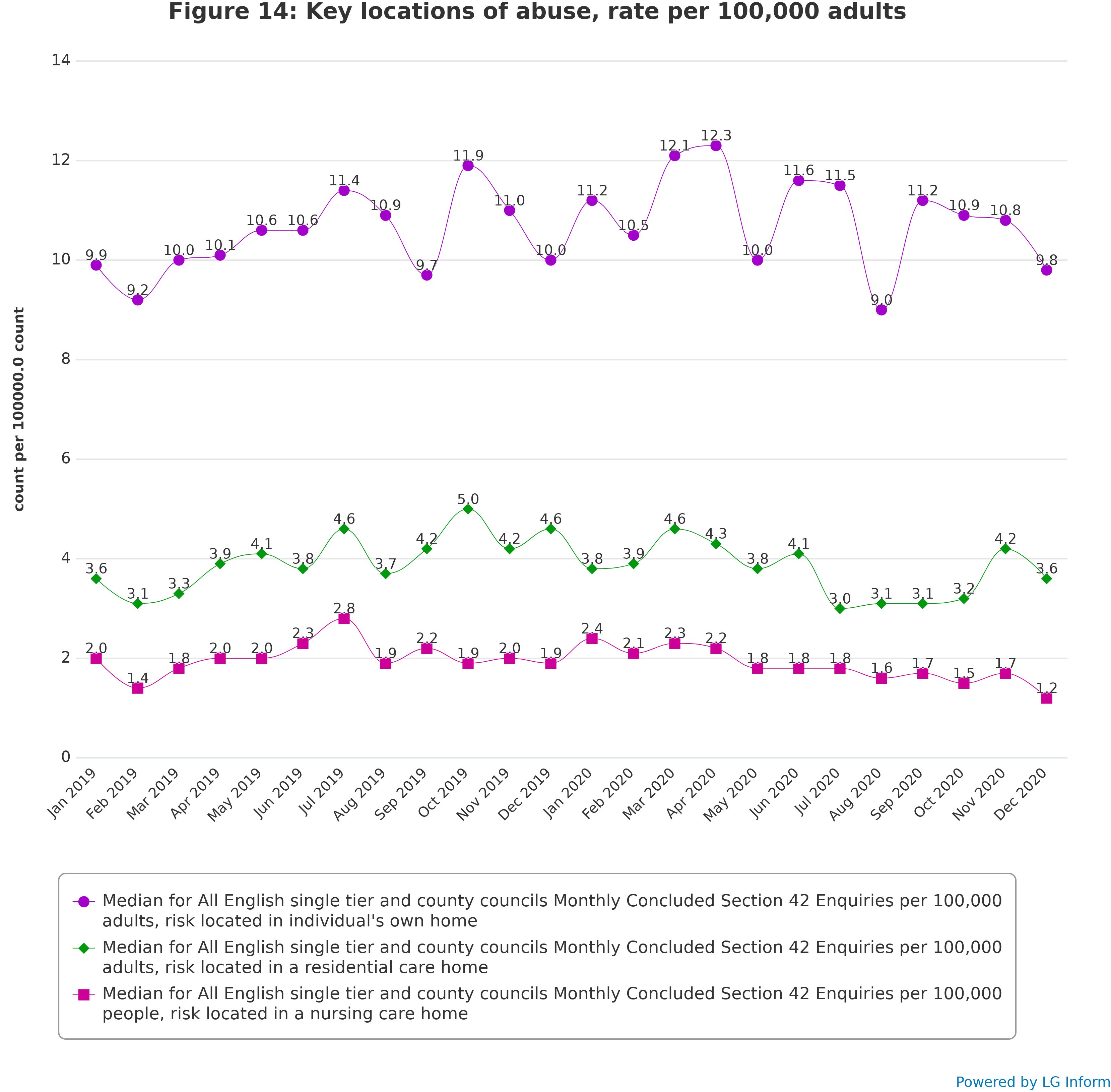

These concerns are partially supported by the data on location of abuse which describes an overall decrease in safeguarding enquiries in both nursing and residential home settings during the pandemic period, with peaks in safeguarding enquiries completed in June and November regarding residential care settings (see Figure 14). Looking at the data collection provided by NHS Digital on safeguarding activity for the period from April to September 2020 regarding both type of abuse and location, neglect and acts of omission within residential care homes increased (although neglect and acts of omission within nursing care homes remained virtually unchanged), rising from 11.4 to 13.5 per cent (see Section 6).

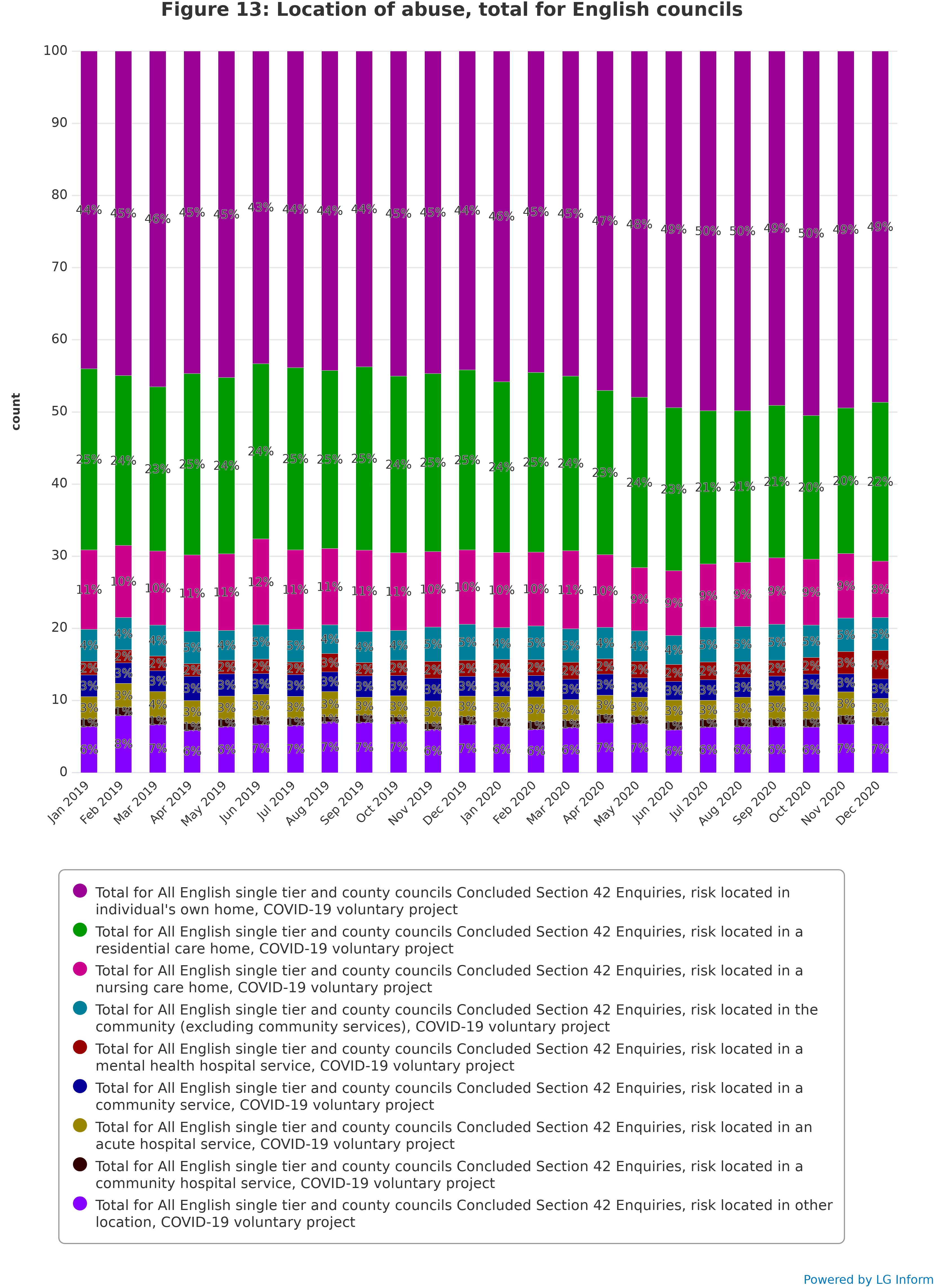

Patterns in location of abuse

Section 42 enquiries with the risk located in the individual’s home increased noticeably during the lockdown period. This tended to be matched by a relative decrease in the frequency of enquiries with risk located in residential and nursing care homes, with other locations remaining constant.

Throughout 2019 around 44 per cent of Section 42 enquiries concerned risk located in an individual’s own home. Starting in April 2020 this generally increased to an average of around 49 per cent. In the same period the percentage of enquiries with risk located in residential care homes decreased on average from around 24 per cent to around 21 per cent, and the percentage of enquiries with risk located in a nursing care home decreased from around 11 per cent to around 9 per cent.

Figure 14 shows that these locations of abuse, as rates per 100,000 adults, have remained roughly the same throughout the period. Nevertheless, as percentages of all Section 42 enquiries these locations have changed because of changes in the overall number of enquiries and changes in the number of enquiries associated with other locations of abuse.

Part 6: Breakdown by type and location of abuse

Patterns of type and location of abuse in safeguarding enquiries

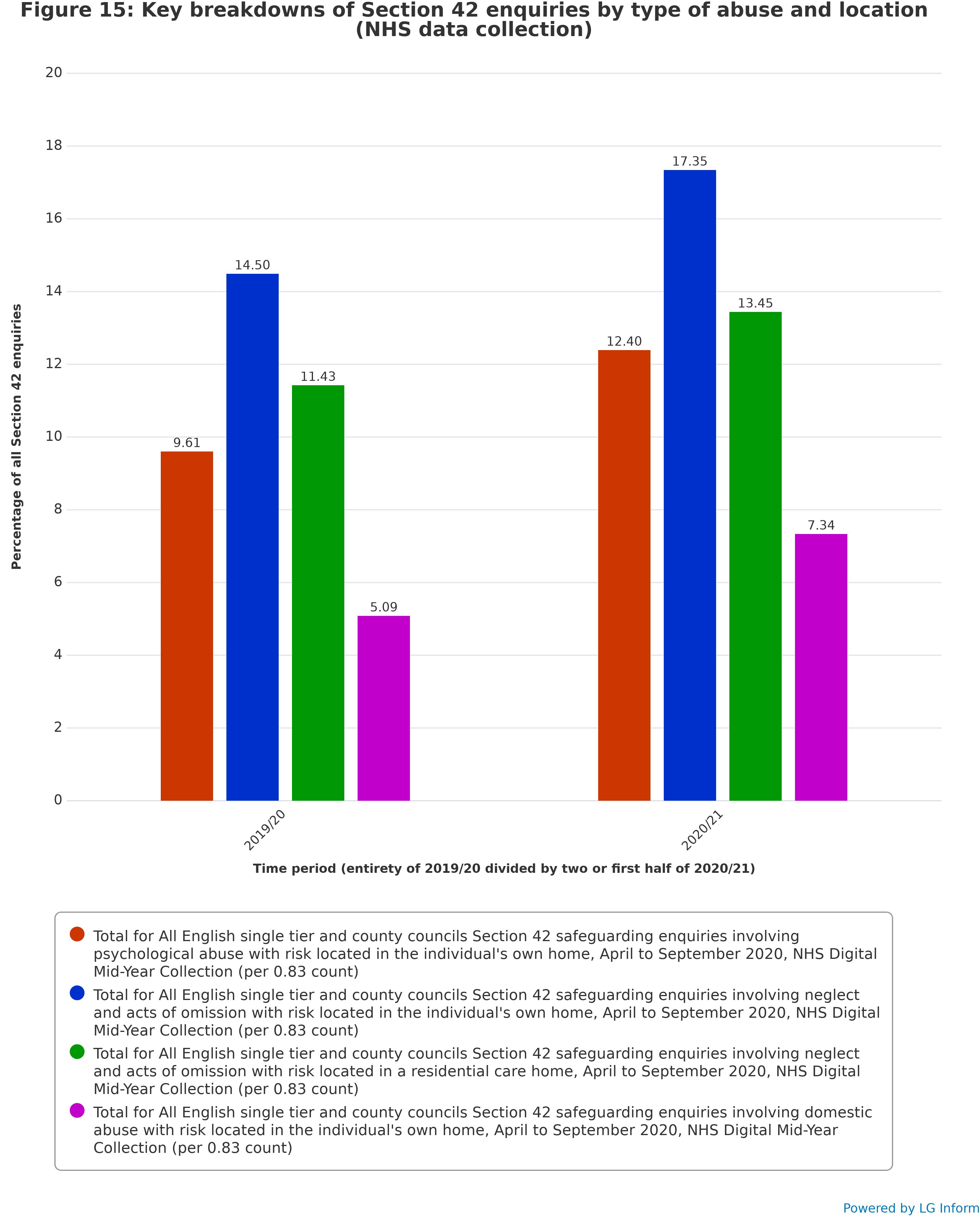

Certain intersections of type of abuse and location of risk experienced marked increases between 2019/20 and the first half of 2020/21, such as psychological abuse, neglect and domestic abuse located in an individual’s own home and neglect located in a residential care home.

This section features data from a mid-year 2020/21 data collection provided by NHS Digital. This collection provided a single estimate for safeguarding activity for the period from April to September 2020, broken down by type of abuse, location, and both type of abuse and location. For comparison with a previous time period, total figures for the financial year 2019/20 were also collected and divided by two. This collection does not provide monthly data.

The mid-year data collection is used for this section because the COVID-19 Safeguarding Insight Project does not collect data breaking Section 42 enquiries down by both type of abuse and location of risk. This is information that is only provided by the NHS Digital mid-year data collection.

As Figure 15 shows, whilst most type-location breakdown categories were extremely uncommon or did not change significantly, certain breakdown categories have increased noticeably from 2019/20 to 2020/21. In 2019/20 cases involving psychological abuse in an individual’s own home constituted around 9.6 per cent of all Section 42 enquiries, whilst in the first half of 2020/21 this increased to 12.4 per cent. Neglect and acts of omission within the individual’s own home also increased, from 14.5 to 17.4 per cent. Neglect and acts of omission within residential care homes also became more prevalent (although neglect and acts of omission within nursing care homes remained virtually unchanged), rising from 11.4 to 13.5 per cent. Finally, cases involving domestic abuse within the individual’s own home rose from 5.1 to 7.3 per cent.

These findings are consistent with the findings of the data from Insight Project returns, showing that the key types of abuse which are either most prevalent or most quickly increasing include neglect, psychological abuse and domestic abuse, with the predominant location of abuse both by prevalence and rapidity of increase being the individual’s own home. Both data collections support and complement each other, with the NHS Digital data offering more nuance with regard to the breakdown of type and location of abuse, and the Insight Project data offering more nuance with regard to a monthly breakdown of safeguarding activity.

Part 7: Breakdown by outcome of enquiry

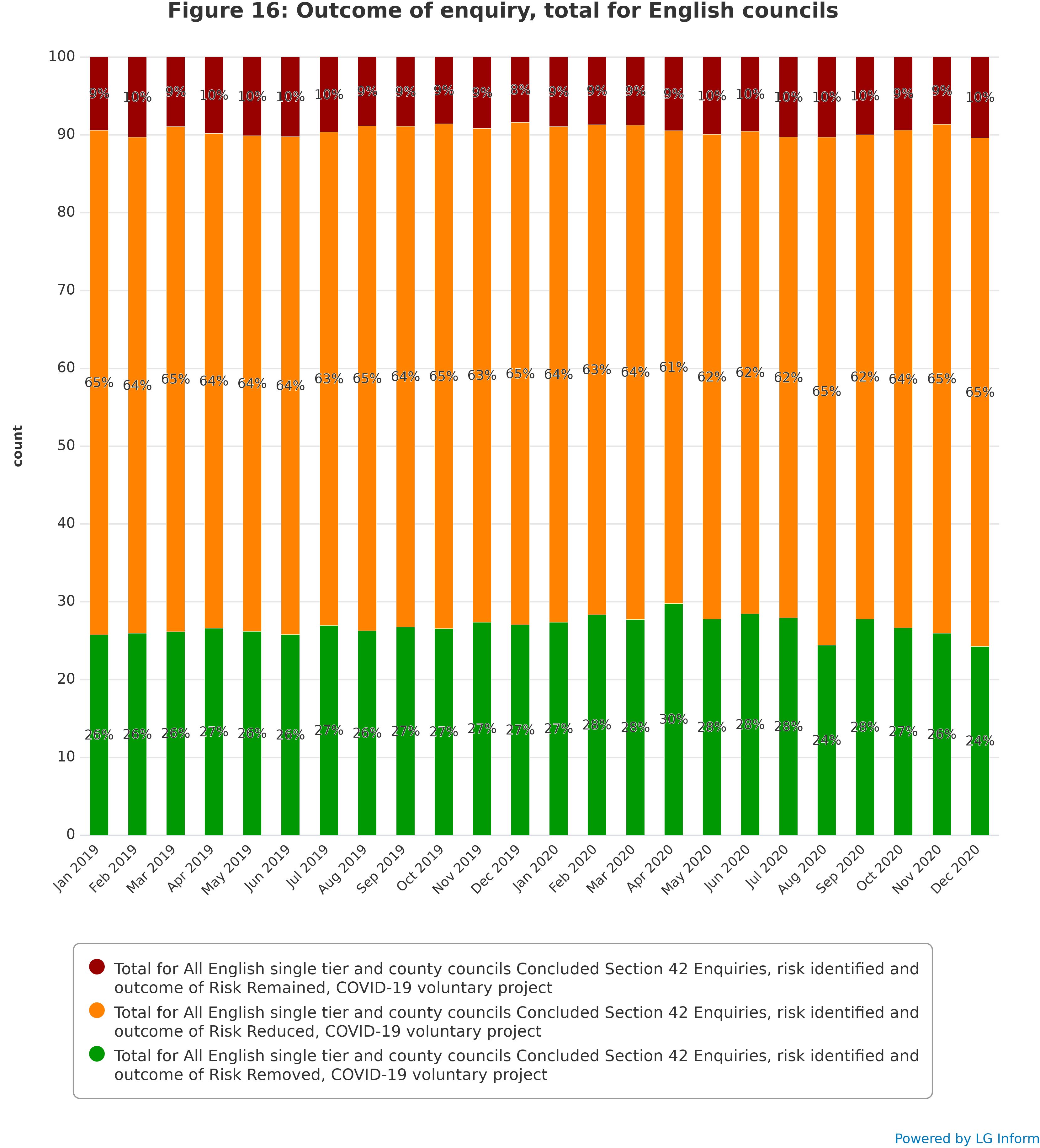

Outcome of enquiry remained relatively unchanged throughout 2019 and 2020, although there was some indication that the proportion of enquiries with outcome of “Risk Reduced” increased in the latter half of 2020, at the expense of “Risk Removed”.

Figure 16 shows that “Risk Reduced” was the most common outcome of Section 42 enquiries throughout the period covered by this data collection, remaining relatively constant at around 64 per cent of all Section 42 enquiries. Enquiries with outcome of “Risk Removed” was the second most prevalent category, at around 26 per cent. Enquiries with outcome of “Risk Remained” remained at a level of around 10 per cent.

Enquiries where the risk remained did not change considerably between January 2019 and June 2020, although the April 2020 figure, at 61 per cent, was slightly lower than the norm. This was mirrored by enquiries where the risk was removed, which remained relatively static, but with a temporary increase in prevalence in April 2020. Enquiries with risk removed were unusually uncommon in August 2020, at around 24 per cent, but increased again in September 2020. This was followed, however, by a steady decrease in “Risk Removed” enquiries leading up to December 2020, matched by a corresponding increase in prevalence of “Risk Reduced” enquiries.

Part 8: Themes around safeguarding in a pandemic

COVID-19 related issues

Councils highlighted safeguarding referrals that were COVID-19 specific, which included: the risk and spread of the virus in care homes, particularly if residents or staff were COVID positive and continued to mix with others; support being declined by people concerned about possible transmission of COVID-19; self-neglect due to concerns about COVID; increased referrals about People in Positions of Trust not following COVID-19 guidance; and local approaches to being able or unable to enter residential settings. Councils, as highlighted in the first insight project report, identified how in the early days of lockdown, emergency service safeguarding referrals increased due to lack of personal protective equipment and concerns about alleged unsafe practice, ie care home staff not wearing personal protective equipment. These also included ‘anxiety driven’ referrals from the increased community contact with shielded and vulnerable residents, particularly regarding self-neglect, although these mostly did not meet the criteria for safeguarding enquiries. Increases in COVID-19 based scams were reported.

Some councils reported that some adults, who were self-isolating or clinically vulnerable, refused access to visiting social care or health staff due to fears of catching COVID-19. It was reported that practitioners often heard information second-hand, which created further distance from the adult who was at the centre of the safeguarding concern. Advocacy services expressed concerns about how personal protective equipment (PPE), particularly masks, creating a barrier to communication between advocate and the adult, particularly where their mental capacity was fluctuating or was borderline.

Safeguarding in regulated services, including care homes

Whistleblowing

Three (of 31) councils mentioned increased levels of whistleblowing regarding care homes and home care services, which reported on people who were not adhering to COVID-19 rules, or issues within care homes such as not having personal protection equipment and inadequate staffing levels. There were also whistleblowing cases regarding hospital settings. Councils described how these cases of whistleblowing required time to unpick as they would often be referring to several different issues, not

only about safeguarding.

Safeguarding in care homes – referrals of concerns

Councils recognised the increased pressure on care homes during the pandemic. The qualitative data describes a very mixed picture of whether adult social care saw an increase, decrease or a plateauing of safeguarding concerns during the lockdown periods. Whilst 48 per cent of councils, who shared their qualitative data, disclosed experiencing increased concerns received during lockdowns, 32 per cent saw decreases and 13 per cent saw broadly the same number. Even within those reporting an increase there were great levels of variance; whilst some saw only ‘slight increases’ others experienced 10 per cent increases in reporting. Further, a council may report seeing a decrease during one lockdown, only to experience expected levels or increase of referrals in subsequent lockdowns and the reverse was also true. For one council they saw increased referrals with a doubling of Section 42 (ii) enquiries for care homes in the lockdown period. Councils identified the following reasons for the increase in safeguarding concerns regarding care homes:

- close monitoring and engagement with the market and providers

- anxiety expressed by care homes around transmission of COVID-19

- low numbers of staff, which caused acts of omission

- increased medical errors

- agency staff unfamiliar with adults they are supporting thus resulting in increased referrals

- confusion over government advice causing providers to “appear to be acting in a neglectful manner”

- increase in incidents between people with learning disabilities who are resident in care homes

- increase in referrals relating to pressure area care and pressure injuries

- increase in referrals where deteriorating health conditions have not been recognised or escalated appropriately

- not wearing or inappropriate use of PPE.

For those councils who experienced decreased rates of safeguarding concerns, the majority said that they saw a correlation with the reduction in adult social care, health and other professionals making regular visits into care home. This meant that visual observations of care home environments and staff practices within the homes were not noted resulting in less reporting of safeguarding concerns. A minority noted that care homes were often focussing on caring and managing outbreaks rather than safeguarding. One council mentioned that they had changed the criteria of what was considered eligible as a safeguarding concern leading to an enquiry, for example not automatically making “one-off medication errors” into a Section 42(ii) enquiry.

A further reported impact of the pandemic and the pressure on care homes was that this caused delays in accessing care homes to undertake safeguarding enquiries and actions. There was also delay reported in convening some safeguarding meetings.

A few councils mentioned of provider 'failure' where issues had become more frequent and intense with the additional weight of the pandemic on top of prior weakness in a provider.

Councils reported that adult social care experienced significant increases in contact from care home providers seeking information and advice. This meant that services were put under increased pressure to provide preventative and reassurance work from social work teams, quality assurance teams, commissioning teams, public health teams and other joint initiatives with health services. These provided a range of support and interventions for care homes to be reassured and supported through the pandemic and protect their residents.

Prevention, innovation, and proactive approaches working with care homes

One of the proactive approaches taken to improve the monitoring and support of care provision mentioned by the majority of councils was the increase of multi-agency meetings to support providers face the challenges of the pandemic: 68 per cent of councils made explicit reference to improved multi-agency working. This included meetings with Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs), quality assurance, adult social care, safeguarding teams, general practitioners, public health, and commissioning, who would meet daily or weekly to compile intelligence, which was analysed to ensure a responsive approach to any emerging areas of concern, including safeguarding risks. These approaches were able to monitor emerging themes such as supply and use of personal protection equipment, reporting and management of COVID-19 outbreaks, deaths in care home, staffing capacity and capability, agency staff use and incident/safeguarding reporting. This enabled councils and their partners to make timely interventions to support care homes or escalate any concerns. Councils described commissioning teams holding weekly group calls with care homes, creating peer support for providers with the aim of resolving common issues, and councils and their partners being able to respond to issues as they emerged.

Councils also reported carrying out remote and verbal engagement with care homes, on occasion this required daily communications, to obtain COVID-19 updates and offer support and assistance as required. Discussions with care homes also enabled them to highlight any specific concerns unrelated to COVID-19. The involvement of commissioning, quality and improvement teams to work with care homes who had an outbreak or single cases of COVID-19 enabled more detailed conversations and actions by officers to gather information on the COVID-19 status of the care settings and identify any emerging risks in care homes. Risks could then be escalated to multi agency meetings where strategies were explored to find potential solutions whether it required guidance, additional guidance and/or additional actions.

A few councils mentioned conducting virtual care homes visits. One council described how they made 188 virtual visits during the nine-months between March and December 2020. These visits resulted in the identifying further support needs which adult social care services were able to resolve or manage.

Carers and safeguarding

The Insight Project was interested in exploring the impact of COVID-19 and lockdown on the experience of carers during the pandemic. 29 councils responded to this question. The interest stemmed from the increased levels of unpaid carers, which Carers UK estimates was an increase of 4.5 million people who began to provide unpaid care since the COVID-19 pandemic. This represents nearly a 50 per cent increase in the number of unpaid carers since the pandemic began. Studies by Carers UK and Age UK have revealed how carers’ mental health, physical health and employment opportunities can be compromised by the impact of caring.

Of the respondent councils 79 per cent described unpaid friend and family carers as experiencing increased “pressure”, “stress”, “isolation”, “frustration”, “exhaustion”, “impact on their mental health” and “burnout” due to the closure of day services, reduced care and support services, which meant increased number of hours caring. There was also some mention of increased behavioural issues and mental health issues for the adult with care and support needs, due to living within a COVID-19 pandemic situation. This was further exacerbated during the winter months where there was a reduced ability to meet safely outside or meet people outside of their household or ‘support bubble’. One council described the impact on unpaid carers as “intolerable” where carers were caring without a break, in addition to working from home and childcare, which had negative mental health impacts on both the carer and the person being cared for. Increased stress levels and isolation, without formal or informal networks of support were reported, and for some this meant increased levels of domestic abuse. Reporting included risks of carer breakdown, due to feelings of ‘being unable to continue in the caring role’. Councils reported breakdowns in care packages due to carer stress resulting from limited access to community services, care support reduced or withdrawn, and the fear and anxiety about the transmission of COVID-19.

Approaches to working with carers

Some councils identified that increased pressures on carers were not necessarily translating into increased levels of safeguarding concerns – there was reporting of either delays in reporting safeguarding concerns or no reports at all. One council described how they had over 100 referrals made to them, where they were able to prevent carer breakdown, and mitigate safeguarding risks. They also had experienced an increased level of referrals regarding young carer referrals. This council commissioned a carers service, which received around 40 referrals since March and provided a “take a break” service, which was an alternative to day centre support as day centres were unable to operate at full capacity. Further this provided support for those carers who were reluctant to send cared-for person to the centre for respite, fearing infection, because of the pandemic. A couple of councils observed that they were more proactive, and would repeatedly offer support to carers, and not assume that they ‘were fine’ as they were not asking for help.

Changes to ways of working impacting on safeguarding practice

The COVID-19 pandemic and lockdowns have dramatically affected the ways in which safeguarding is practiced and this section summarises the insight provided by participating councils covering both the challenges and innovative responses to them.

Working flexibly and adapting to new ways of partnership working

During the pandemic councils were facing additional workloads on top of their ‘business as usual’ work. As described in Part 1 of this report, the work with shielded and clinically vulnerable residents, community outreach and emergency service contact led to increases in reporting of safeguarding concerns. Many councils described an increase of reporting “low-level harm” or safeguarding concerns that did not meet the Section 42(ii) criteria’ (depending on reporting methods). One council described that they considered this a “positive” sign that demonstrated increased partnership working, showed a great level of transparency and a more proactive approach to support. This partnership working could enable early identification of themes and trends to develop proactive approaches to counter issues as they arose. Reporting systems were also put in place to ensure learning had been embedded and sustained change. Conversely some councils reported that adults were not accessing community resources and as a result seeing they was a reduction of community-based safeguarding concerns.

Reduced face-to-face working

Councils reported that the pandemic meant that there was less face-to-face interaction in safeguarding activity to reduce risks of transmission: for some this meant an approach to stop almost all ‘in person’ interaction; for others there was more discretion allowed with time sensitive and/or more urgent safeguarding concerns being dealt with in person. There were varied approaches with some councils expressing caution regarding over-reliance on technology over in personal contact..

Whilst Making Safeguarding Personal has always remained central to all safeguarding practice with adults, Councils reported that it was more difficult to enable this approach during the lockdown periods and has required careful planning to deliver. There were concerns that reduced numbers of face-to-face assessments were resulting in less opportunity for safeguarding disclosures. There were also concerns that the person talking with a carer present could be a barrier to reporting or disclosing abuse. Similarly, concerns were expressed about reduced access to care homes, due to risk of COVID-19 transmission, meant that fewer safeguarding concerns were disclosed.

IT and video conferencing: pros and cons

Video conferencing, most commonly in the form of Zoom or Teams, has emerged as one of the most powerful and constructive tools to support practitioners to navigate through the pandemic, to maintain communication and practice. This has enabled the creation of virtual multi-agency/partnership working. Councils reported that partners were meeting on daily and/or weekly basis, most commonly through these video conferencing platforms. Most councils spoke of embracing this new way of working and 68 per cent of councils (21 of 31) explicitly mentioned improved collaborative working with partners during the pandemic. More frequent and regular meetings have been able to be set up than before the pandemic and these are reported as better attended then previously. Councils reported forming new partnerships, increased networking, and regular engagement with a wider group of providers. Whilst the overall picture was increased positive relationships with partners during the pandemic, there were also strained relationships reported, with health colleagues. These were considered to be due to different priorities, for example pressures to discharge people from hospital; competing for PPE; prioritising COVID-19 vaccinations for health staff rather than social care staff. Relevant to safeguarding activity, there were reports that in some cases information from health partners was shared in a less timely manner when safeguarding enquires were being carried out due to pressures on health services.

Councils reported that virtual meetings ensured that safeguarding responsibilities and duties could be maintained at a Safeguarding Adults Board (SAB) level. There were examples cited of Heads of Adult Safeguarding having weekly virtual meetings with the Chair of their SABs. Councils reported that these SAB meetings were sustained as these were arranged virtually.

Some councils reported that the number of meetings increased for collaborative decision making by professionals, who were unable to physically meet with adults and so were more reliant on each other to make sense of a situation and to support each other and the person they were working with. Other councils spoke of arranging virtual monthly meetings with all safeguarding adult operational leads including adult social care, police, hospital, CCG, housing, and their mental health trust, which:

... enabled any trends or issues to be identified and addressed. Following the first lockdown, the monthly meetings with the operational leads continues as partners have found them to be helpful. This has embedded a transparent, supportive strategy. We have also seen much closer partnership working across children’s and adults’ services, especially with the complex safeguarding hub and aftercare."

Other councils described how they were having more virtual safeguarding enquiry meetings and risk framework meetings. It was reported that the virtual media also enabled adults to engage in meetings:

They had the power to have cameras off and the ability to participate discreetly in the background, which allows people to be a part of the proceedings in a way that suits them better than being physically present."

Some councils described how this way of communication could also form part of an offer within a suite of options of how a person may choose to engage with the safeguarding process after COVID-19 restrictions ended. This also appeared to get greater engagement from practitioners as well in virtual meetings.

MS Teams has enabled and encouraged better involvement of practitioners and agencies in safeguarding enquiry meetings and risk framework meetings and this includes the police, probation and external housing providers."

Councils also noted that this change in using video conferencing did not suit all people, particularly some older people. Some people preferred to use of their phones rather than their computer video participation. However, even the more conventional phone call proved to be a valuable participatory option during the pandemic. Use of video conferencing has meant that meetings could be set up swiftly and it ‘sharpened the communication skills’ of practitioners over the phone with adults when discussing their concerns.

The negative impact of using virtual platforms/video technology/technology was also commented on by participants. 22 of 30 councils expressed the loss of face-to-face as being a challenge and reported on the difficulties of substituting technology in place of face-to-face contact. For example, when conducting a safeguarding enquiry process in a care home, where practitioners had limited access, using technology to talk to people or gain information from staff was problematic when it did not always work well, or if the person was reluctant to speak in front of care home staff. In these situations, some councils reported of agreeing ‘in-person’ meetings on an exceptional basis to obtain complete and accurate information. Whilst technology was invaluable in the pandemic to support practice, it was not always effective.

One council highlighted inequity of access to information technology where internet provision was not always available, for example for adults in supported living arrangements, or where the on-site internet was only available for staff use and so the advantages of new technological initiatives could not be fully realised by these adults. However, in these cases councils ensured that there were alternative and appropriate provision for people to communicate to practitioners by other means, for example the phone.

Councils also expressed some negative consequences of video conferencing, such as adults being able to disengage by switching off their connection. There was also a negative impact reported on Making Safeguarding Persona as some people were less likely to participate in video conferences. There was recognition that video conferencing could change the outcome and the conversation. In some cases, the adult with care and support needs required support to access or use the virtual platforms. Unfortunately, this could increase barriers to engagement, if the safeguarding disclosure to a practitioner was about the technological enabler, or they were the potential source of a safeguarding concern.

Oldham Council case study

We developed a Discharge Bronze group, which has all partners within it, GP, health trust, care homes, social care, commissioning, and the like. Within this meeting we discuss all strategies for discharges and any barriers and how to unblock these. We will also consider any unsafe discharges, and work through ‘lessons learnt’ what didn’t work, and what could have been done differently, and implement any changes. We found this affective as it was multi-agency, and everyone committed to the same outcomes, when back to their agencies, reflected and made appropriate changes.

We also had situation report daily calls with care homes to gather situation report information. This involved discussions on staffing levels, PPE equipment, agency staff etc. These were discussed initially on a daily care homes meeting (which again was multi-agency) including Public Health. Within these meetings we reflected on and analysed the information, alongside low-level harm logs and safeguarding data/emerging risk. For example, if the care home was significantly understaffed due to COVID, this would mean that support/supervision would be reduced. This could potentially mean that people were at increased risk of falls/pressure sores and the like, which would increase the safeguarding risk.

We did see this correlated in information on comparison in the situation reports (low staffing levels/staff isolating co-related to increase falls). We didn’t want the care homes to see our intervention/reporting of these as negative, so we adapted our communication to ensure if reflected open, transparent, joint working and support. More of a ‘we are all in it together’ approach. If the care homes reflected a challenge, we were able to support with resources, either by Supporting Treatment in Care Homes, District Nursing, infection control, training etc. This worked well. We have seen significant increase in reporting, which we consider a positive as it demonstrates transparency and trust. We do also see ‘over reporting’ but we would rather the services over report, it is more concerning when there is no reporting at all.

We also developed Safeguarding Assurance meetings on a weekly basis as a Safeguarding Adults Board. This enabled us to identify risks and themes and go to our partners to ask for assurance plans and held us accountable for what we were doing. During the COVID-19 pandemic we have developed a timeline at what we did, and which point, why and what was the outcome. We also discussed the impact on interventions.

At the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, the safeguarding referral rates dropped. We recognised this and proactively did campaigning with care homes, police, Community Hubs (providing training for those delivering food parcels), District Nurses etc. about what a safeguarding concern is and how to report it. We also used social media, our website and Twitter. It was in every conversation. As a result of this, you instantly see a rise in the concerns reported, so we know this was effective. We were then able to adapt this approach again, each time we saw a dip in referrals, usually correlating with a lockdown starting. This has now enabled us to be more proactive in planning, rather than reactive.

When we saw the referral rates rise, concerning domestic abuse, we did a Facebook live session with the police, IDVA, MASH and voluntary agencies, as we knew that people were using social media more. This was a secure Q&A session, where people could ask advice, report concerns and ask for support. This was effective. We were able to do this twice, and we saw an increase in people accessing support.

Bournemouth, Christchurch, and Poole Council case study

When people had a roof and a little more structure, they seemed more motivated to engage with workers who were dropping food parcels to them, this led to steady conversations about the future. Some people began to talk about entering treatment for addiction or mental health, some engaged in plans to secure more permanent accommodation.

Bournemouth, Christchurch, and Poole Council noticed a rise in the number of safeguarding concerns being raised by volunteers who were visiting people who were shielding. This also offered an opportunity to offer advice, support or signposting in most cases and to assertively engage with people who had more significant difficulties.

There was a real push to look for a preventative approach. The self-neglect panel had a wide range of professionals in attendance, including housing, fire service, environmental health, and social care. Practitioners attended virtual meetings to discuss and see how best to work with a person, which enabled agencies to get involved. There was often a single practitioner who was in contact with the person, who was closest to the them. These opportunities for assertive engagement, have made Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole Council’s Adult Social Care safeguarding lead reflect on how they might be able to work with people who are self-neglecting differently in the future and it has informed the council’s Homelessness Strategy.

Part 9: Consultation on the future of the Insight project