Commissioned by

The Local Government Association (LGA) is the national voice of local government, working with councils to support, promote and improve.

The LGA has been working with a group of seven councils on the Reshaping Financial Support programme looking at how to design and implement early intervention financial support and services that can prevent low income households developing further financial issues.

- Brighton and Hove City Council

- Bristol City Council

- Leeds City Council

- London Borough of Tower Hamlets

- London Borough of Barking and Dagenham

- Newcastle City Council

- Royal Borough of Greenwich

COVID-19 has seen the programme refocus specifically on the unfolding response to financial hardship and economic vulnerability, working collaboratively to explore their experiences and challenges and develop new solutions/approaches. The group widened to include representatives from:

Birmingham City Council, Cambridgeshire County Council, Colchester Borough Council, Devon County Council, Gateshead Council, Hertfordshire County Council, Kent County Council, London Borough of Islington, London Borough of Southwark, Nuneaton and Bedworth Borough Council and Stevenage Borough Council.

Contact: Rose Doran (Senior Adviser) - [email protected]

Produced by

The Financial Inclusion Centre (FIC) is an independent research and policy innovation think-tank dedicated to reducing financial exclusion.

Written by: Gareth Evans and Matt Earnshaw

Contact: Gareth Evans

Collaborative foreword

The Money and Pensions Service

The Money and Pensions Service (MaPS) understands the important role that local authorities play in supporting the financial resilience and wellbeing of their communities, and we have seen how effectively and speedily individual councils have responded to the impact of COVID-19 on vulnerable households and communities.

We will work in partnership with the LGA and local councils to realise the ambition of the UK Strategy for Financial Wellbeing through to 2030 once we publish the delivery plans later this year. Alongside the many other initiatives currently being implemented, councils have the capability to offer and promote options that will enable households to better harmonise council tax payment cycles with income and spending patterns.

MaPS looks forward to continuing its engagement with the LGA and to support such initiatives as part of our wider collaborative partnership to support the financial wellbeing of households across England.

Fair4All Finance

The current financial services system is designed for predictable lives and incomes. Yet around 14 million people in financially vulnerable circumstances are living with unpredictability.

When faced with unexpected costs like a broken boiler or washing machine many of us have safety nets to fall back on like overdrafts, credit or savings. But for those on low or insecure incomes and the 11.5 million with less than £100 in savings, these are not an option.

With their community links, councils also have an important role to play. In particular affordable credit can be an important part of a joined-up welfare strategy for councils, fitting into supportive local ecosystems alongside debt advice and other welfare support. We’ve seen excellent examples of deep collaborations between councils and community finance providers that have successfully sustained the provision of affordable credit.

We know the impact of serving people in these circumstances well can be profound. It goes way beyond financial savings with healthier diets, improved sleep and better physical and mental health just some of the other benefits.

By improving the availability of fair and accessible financial products and services, ones that will help people meet their day-to-day financial needs, absorb shocks, smooth incomes and build resilience, we can provide people with pathways to better financial health and wellbeing.

Fair By Design

For many years, we’ve been battling a twofold problem: firstly, the reliance on personal credit to deal with low incomes and the rising cost of living. And secondly a small but harmful section of the consumer credit market that has increased its grip on low-income households quicker than the government and regulators could act. Research commissioned by Fair By Design shows this isn’t a problem we can afford to ignore. The extra costs of using forms of high-cost credit every year ranged from £42 for catalogues to £644 for home collected credit. While the costs of buying goods on credit from a rent-to-own shop has decreased on average since 2016, it has dropped from £315 to a still eye-wateringly high £182.

That is why this report is so important. A vital part of any national strategy on affordable credit must include credit availability at a local level. Our view is the more local the strategy, the better the links between providers and customers. Organisations working on the improvement of affordable credit have achieved so much in recent years. This is very exciting. Of course, there’s further to go but we have the momentum behind us.

Centre for Responsible Credit

The COVID-19 pandemic has emphasised the importance of councils in providing strategic, and effective, responses to debt. An effective response in local communities requires local leadership. Councils have the mandate to bring together the wide range of stakeholders needed to create more joined up support. They also either directly deliver or commission support services – and administer discretionary hardship funds and, of course, are creditor agencies, seeking the recovery of council tax and rent.

Combining these roles is challenging, especially with current increased demand for support services and reduced revenue collection. But, if anything, it demonstrates the need for greater investment, and the urgent exploration of new ways to meet the needs of people who are struggling financially. To determine the need for, and role of, grants and affordable loans alongside advice to help people recover; to provide greater flexibility in bill repayments, and more strategic approaches to debt recovery moving forwards. The need for a comprehensive reshaping of council approaches has never been greater.

The Finance Innovation Lab

The UK financial sector is woefully bad at serving low-income households. To address this problem at its root, we must grow the purpose-driven banking ecosystem which includes credit unions, community development financial institutions, building societies, ethical banks and mutual banks – that are driven by a social or environmental mission. We think the time to build this is now and councils have a vital role to play. They can help to tackle the systemic barriers the sector faces, including low public awareness, a regulatory system set up to suit the big banks, and access to capital.

Executive summary

As illustrated throughout this guide, the case for supporting people to access affordable and responsible finance from organisations like credit unions and Community Development Finance Institutions (CDFIs) is clear. Indeed, some councils already have a long history of working with these organisations to support the financial wellbeing of their residents and communities.

The deteriorating economic conditions and growing levels of financial hardship caused by the COVID-19 pandemic have generated an increased need to ensure that affordable and responsible credit is available alongside a strong welfare safety net and direct financial and in-kind support. Credit isn’t an appropriate solution for everyone, but for those who need it to smooth income fluctuations or deal with short-term financial problems, it is vital that it is affordable and helps build financial stability and resilience as part of the longer-term social and economic recovery. However, even before the start of the pandemic, the Money and Pensions Service (MaPS) and Fair4All Finance highlighted the scale of the challenge facing affordable finance provision across the UK, evidencing that high-cost credit providers, such as doorstep or payday lenders, were lending more than ten times as much as affordable credit providers - £3 billion of lending compared to £250 million.

Given their role as local community leaders and place shapers, and ongoing work with credit unions and CDFI’s, councils are well placed to support, develop and promote the delivery of affordable and responsible finance within their areas as part of a wider financial inclusion strategy. The LGA continues to highlight to key stakeholders, the work of councils on this agenda, and the significant value they could add with additional strategic backing and support, as part of a comprehensive and integrated approach.

This guide is not intended to be prescriptive, but to offer councils ideas and experience that may enable them to make the best use of available resources, maximise the effectiveness and value of their local approaches. This ensures that they are well placed to work within a strategic partnership to drive forward positive change in the provision of affordable and responsible finance, for the people and communities that need it the most.

Setting the context

The strategic framework provided for the affordable credit agenda by the Money and Pensions Service and Fair4All Finance can be used to inform and guide councils’ approach to improve access to affordable financial services within their local communities. Developing activity in line with the identified goals and objectives within this framework will ensure strong alignment between local delivery and national strategy and demonstrate the critical role that councils can play in the delivery of the financial wellbeing agenda.

Evidencing need and demand

Local approaches to the provision of affordable credit should be evidence-based and built on a robust and detailed understanding of the needs of the local community. This is vital to maximising the effectiveness and value of local delivery, ensuring its scale meets local needs and that it can be targeted to those who need it the most.

Building a holistic evidence base that includes modelling of the potential scale and cost of existing high-cost credit use will enable senior management and elected members to make informed decisions about investment in local affordable finance provision.

Building a business case

Calls for support or pitches for investment should be underpinned by a quantifiable business case that includes a clear illustration of the impact and value it will generate and the return on investment that will be provided for residents, the council and wider community.

Alongside building up a picture of subprime credit use, it can also be useful to understand the scope of any existing affordable credit provision across local communities, to help identify the scale of the gap between supply and demand. Whilst this data isn’t routinely published, councils can engage with local affordable lenders to understand what data might be available for their local areas and to discuss potential data sharing opportunities.

Working with community lenders

Councils should consider investing in credit unions via subordinated debt or deferred shares. Given the financial pressure on councils, investing in credit union capital can allow credit unions to expand their operations while retaining the investment as an asset on the council’s budget sheet, which may present a more attractive funding proposition than a grant.

Affordable lenders can often provide flexible and tailored products to meet the different needs of partner organisations. Councils should therefore identify how affordable finance products could be best used to support cost-effective council service delivery, and engage with local providers to discuss potential product development opportunities.

Through their engagement with, and support of, affordable lenders, councils should encourage and facilitate the adoption of the Affordable Credit Code of Practice as necessary. Additionally, the criteria highlighted within the code could be used to inform future commissioning / contracting processes for affordable finance provision, to ensure the quality and effectiveness of local services.

Ensuring that affordable finance provision is robustly integrated with wider support services, including those of the council and local voluntary and community sector partners, should be a key underlying principle to convert short-term support into longer-term financial stability by addressing wider circumstances and needs. Given their leadership role within local communities, councils are well placed to ensure that the right partnerships are in place to facilitate this co-ordinated approach.

Delivering effective promotion and communications

Promotional and awareness raising activity should be informed by relevant behavioural insights research and resources to ensure that it is as engaging and effective as possible. Activity should be targeted to ensure that those most in need can find out about the support available and this should include the use of partners working with vulnerable residents

Practical opportunities to embed relevant information, resources and support tools across council activity and processes should be mapped out and prioritised. For example, embedding reference to local affordable finance provision and the ‘stop the loan sharks’ team within relevant council tax communication processes. External resources and tools can also be used to add value to local information.

Measuring impacts and value

Robust impact measurement and evaluation should be embedded within the delivery of affordable finance, enabling the council and its affordable finance partner(s) to track the impact of support on residents, the council, wider community and local economy. Appropriate measures should be agreed and included in any partnership agreements or contracts, alongside the standard output-based KPIs.

Tools to measure social return on investment or social value can be used to undertake predictive impact modelling of new affordable finance proposals, providing a considered estimation of the likely impacts and value that will be delivered. This can help to strengthen the business case for affordable finance. and should be included in any proposition for investment presented to the council or external stakeholders.

1. Introduction

Alongside the welfare system and other forms of financial and hardship support, credit is an essential tool that enables households to smooth fluctuations in income, pay for unexpected events and cover periods of increased expenditure such as school holidays. Unfortunately, many people are unable to access lower-cost credit like bank credit cards and loans as they are financially vulnerable, on low or unstable incomes, or have a bad credit history. Many of those in this position will therefore unfortunately turn to high-cost credit, such as payday lending, rent to own or home collected credit, to help meet their needs because they do not have, or perceive that they do not have, any other alternative. The scale of high-cost lending in the UK was already significant before the start of the coronavirus crisis, with the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) estimating that three million consumers were using high-cost credit (excluding overdrafts) on a regular basis.

As the coronavirus crisis has continued, the impact on people’s finances has been significant. The FCA report that 12 million people across the country now have low financial resilience, meaning they may be struggling to pay their bills and manage everyday living costs Whilst StepChange, the debt charity, have estimated that 29% (15 million) of adults have experienced at least one negative change of circumstances since the beginning of the outbreak, including redundancy, a reduction in the number of hours worked, furlough with a reduction in salary, or a fall in income from self-employment. They also evidence that 1 in 3 of those affected negatively by coronavirus (4.9 million) have borrowed to make ends meet due to their reduced income, with an estimated 9% having used one or more forms of high-cost credit and 2% an illegal money lender. Those in the most vulnerable circumstances face a poor choice of options – go without, go into arrears or take out high-cost credit, which can drain their already limited income with high interest repayments, and push them into significant hardship.

The case for supporting people to avoid high-cost credit by improving access to lower cost credit via community lenders such as credit unions and Community Development Finance Institutions (CDFI’s) is therefore clear. It not only helps people to deal with short-term financial problems and manage uneven income, but also builds financial stability and resilience that can prevent future financial problems and save costs in the longer term. This should not be seen in isolation, but alongside a holistic package of financial support (such as income maximisation and debt advice) and discretionary funds that ensures the most appropriate outcomes are delivered for the individual’s circumstances.

Given their role as local leaders and place shapers, councils are well placed to support, develop and promote the delivery of affordable and responsible finance, ensuring that it meets local needs and priorities. This toolkit is aimed at providing a range of relevant evidence, good practice and learning to support the role of councils in improving access to affordable and responsible finance for their residents and local communities. It highlights a range of case studies, alongside practical resources, reports and websites, across all aspects of improving access to affordable finance, that can be used by councils to build sustainable, impactful partnerships with credit unions and CDFI’s for the benefit of their residents as well as their local communities and economies.

2. Setting the context

This section details some of the most relevant reports and strategies in terms of identifying and setting the context for the role of councils in improving access to affordable and responsible credit and financial services for low-income households.

Strategic context

UK Strategy for Financial Wellbeing – Money and Pensions Service (MaPS), 2020

The UK Strategy for Financial Wellbeing sets out a national strategy to significantly improve financial wellbeing over the next 10 years. It provides a simple, clear set of goals to focus the efforts of all organisations working to help people to manage their money and deal with financial crisis.

Managing credit (Credit Counts) is identified as one of the five priority ‘agendas for change’ within the strategy, with a national goal of 2 million fewer people using credit for food and bills by 2030 and outcomes relating to more people accessing affordable credit and making informed choices about borrowing.

Credit Counts: Affordable Finance – MaPS and Fair4all Finance

Following on from the Financial Wellbeing Strategy, this document sets out a more detailed framework for the delivery of the Credit Counts agenda and highlights some of the strategic issues that need to be tackled to improve access to affordable and responsible credit.

Transforming Affordable Credit in the UK – Fair4All Finance, February 2020

Fair4All Finance was founded in 2019 to support the financial wellbeing of people in vulnerable circumstances. Funded by dormant assets money for financial inclusion, Fair4All Finance looks to increase the financial resilience of people in vulnerable circumstances by increasing access to fair, affordable and appropriate financial products and services.

Alternatives to High-Cost Credit Report – Financial Conduct Authority (FCA), 2019

This report examines the market for alternatives to high‐cost credit by looking at consumer demand and the availability of credit and non‐credit alternatives. The report notes the critical role of front-line service providers in supporting people to access affordable and responsible credit.

This document sets out Fair4all Finance’s approach towards delivering the Credit Counts agenda, including a detailed Theory of Change for every organisation that is contributing to resolving access to affordable credit in the UK.

Key considerations

The strategic framework provided for the affordable credit agenda by the Money and Pensions Service and Fair4All Finance, can be used to inform and guide councils’ approach to improve access to affordable financial services within their local communities. Developing activity in line with the identified goals and objectives within this framework will ensure strong alignment between local delivery and national strategy. It will also demonstrate the critical role that councils can play in the delivery of the financial wellbeing agenda.

3. Evidencing the need and demand

This section summarises relevant research and data sources that can be used to develop a localised need/demand evidence base for affordable and responsible credit. This can help to build the business case and secure support for investment in relevant service provision. An evidence-based approach will maximise the effectiveness and value of local delivery, ensuring scale meets local needs and can be targeted to those who need it the most. Data sets relating to a wide range of issues, including poverty, financial vulnerability, subprime credit use and the impacts of COVID-19, are highlighted to ensure that a holistic evidence base can be developed

Poverty and deprivation

Understanding the local scale of poverty and deprivation provides important contextual information on the potential need and demand for affordable and responsible financial services. Identifying levels of unemployment, benefits claimants and low-incomes, alongside other markers of vulnerability, can provide an indication of the number, or scale, of households likely to be under financial pressure or at risk of financial hardship, which has direct implications in relation to borrowing and debt.

Measures of local deprivation

The Indices of Deprivation combine a range of economic, social and housing indicators to provide a measure of relative deprivation (i.e. they measure the position of areas against each other within different domains). This data therefore provides some useful baseline information for localities in terms of existing deprivation levels.

Other useful indicators

|

Unemployment |

Income support claimants |

|

Incapacity benefit claimants |

Housing benefit households |

|

Carers allowance claimants |

Fuel poverty households |

|

Universal credit claimants in employment |

Children living in relative low-income families |

|

Pension credit claimants |

Households assessed as threatened with homelessness |

A wide range of data sets and reports can be accessed via LG Inform – the local area benchmarking tool from the LGA.

Financial vulnerability and resilience

Analysing data relating to levels of financial knowledge, skills and confidence, over-indebtedness, savings and credit scores, can help to evidence the potential scale of financial vulnerability and resilience that exists among local populations. Financial vulnerability and low levels of resilience impact on the financial issues and pressures faced by local households and, therefore, the options that are available to them to access affordable and responsible financial services. Additionally, whilst vulnerability existed pre COVID-19, the economic impacts of this crisis and increasing financial hardship will exacerbate the scale and impact.

The national context

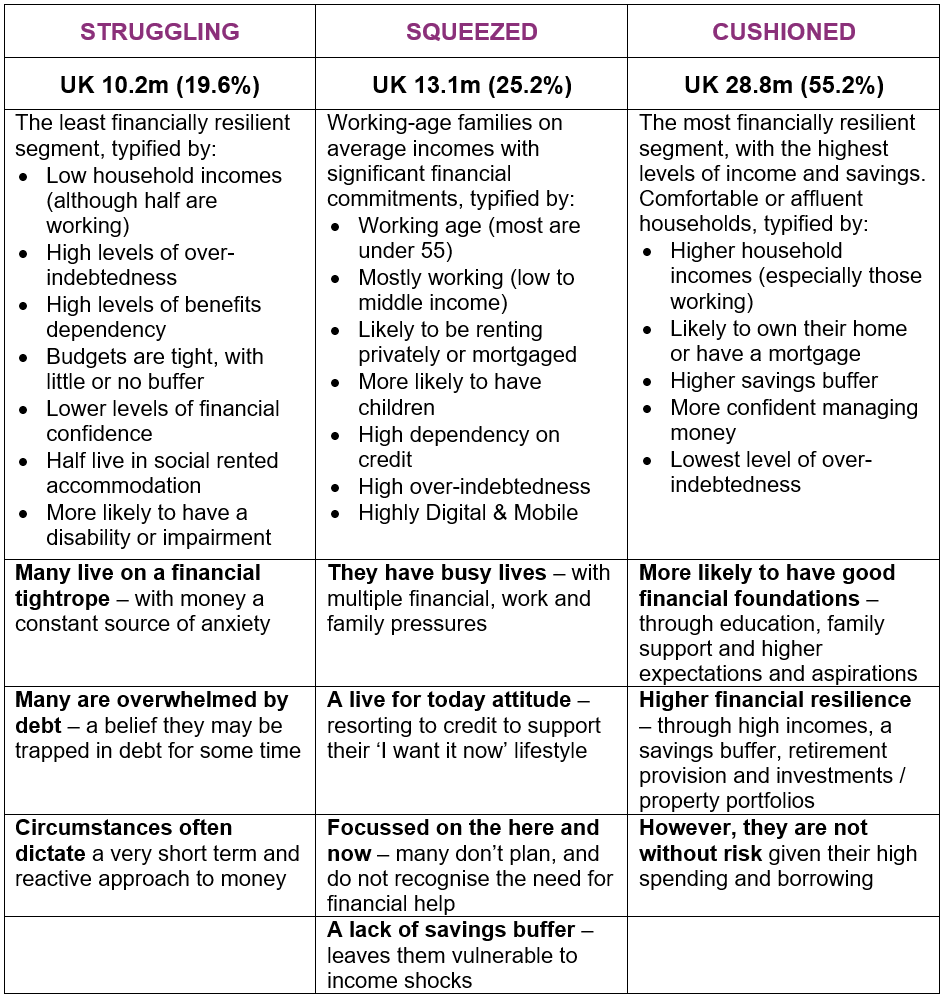

At a national level, MaPS have undertaken a consumer segmentation focused on financial resilience and how people manage their money. They undertook this work to help identify and profile the different groups of people that exist and to understand their specific financial and advice needs. MaPS identified three distinct groups across the UK population:

- those who are Struggling (the least financially resilient group), who make up 19.6% of the population

- those who are Squeezed (working-age families on average incomes with significant financial commitments), who account for 25.2%

- those who are Cushioned (the most financially resilient group, with the highest levels of income and savings), accounting for 55.2%.

Further detail on the segment profiles is highlighted in Appendix 1, whilst several relevant documents are on the MaPS website.

Financial Lives Survey

The Financial Lives Survey is a large-scale survey of UK adults, undertaken by the FCA to aid their understanding of consumers in the retail financial markets they regulate, including in relation to their financial situations and their attitudes towards managing their money. It therefore provides some useful insight into levels of financial vulnerability and resilience.

The 2020 study provides several findings for the UK as a whole and also by a range of other geographic areas, including NUTS 3 areas (comprising counties or groups of unitary authorities). The following indicators, which are particularly relevant to financial vulnerability, can be viewed across different geographical areas via an interactive map.

Indicators

- How knowledgeable would you say you are about financial matters?

- How satisfied are you with your overall financial circumstances?

- How confident do you feel managing your money?

- I am confident using credit – it feels normal to me

- I like to stick with a financial brand I know

- I’d rather think about today than plan for the future

- Over-indebtedness

Over-indebtedness

The Money and Pensions Service (MaPS) produced a research study (2018) to estimate the levels of individual over-indebtedness within all regions and local authorities across the country. Over-indebted individuals are defined as those that either: find meeting their monthly bills / commitments a heavy burden; or have missed bill payments in three or more months out of the last six months.

Public sector debts

The levels of debts that households owe to the council for rent arrears and council tax arrears could also be mapped and analysed to create a full picture of financial issues within an area.

Credit scores

Another indicator of potential financial vulnerability is an individual’s credit score. This highlights how likely you are to be accepted for credit based on your credit report, which is a record of how you have handled credit in the past. Credit scores are determined by various factors, including missed payments, debts, county court judgements and insolvencies which all drag down credit scores – equally, a lack of previous borrowing can also negatively impact credit scores.

The Experian Credit Score Map provides the average credit score for 391 areas across the country

The Good Credit Index

Good Credit Index, produced by Demos, maps access to credit across the UK. Combining several public and private data sets measured at the local authority level, the Index is more granular and comprehensive than previously possible. It is divided into three strands:

- credit need (including variables such as income, the percentage of people struggling to keep up with bills and the volume of credit searches)

- credit scores (including rates of CCJs and insolvencies as well as average credit scores)

- credit environment (the number of payday lenders and pawnbrokers but also bank branches and credit unions on the high street).

The Index ranks 387 local authorities in relation to their scores for these three strands. Higher Index scores relate to areas where the need for credit is lower and credit scores are high, whilst the authorities with the lowest Index scores are highlighted as ‘credit deserts’ – places where high need for credit coincides with low credit scores and an overrepresentation of unaffordable lenders.

COVID-19 and financial hardship

Produced by the LGA and the Financial Inclusion Centre, the Financial Hardship and Economic Vulnerability Demand Dashboard can be used to produce a summary report of financial hardship and economic vulnerability as a result of COVID-19 at local authority level.

Sub-prime credit use

Estimating subprime credit use

The FCA have previously undertaken a strategic review of High-Cost Credit within the UK, which included detailed analysis of the market size and customer profile of different types of high-cost credit such as High-Cost Short-Term Credit (HCSTC), also referred to as payday loans, Home Collected Credit, also referred to as doorstep loans, and Rent to Own. Whilst this data is predominantly referenced at a national level, it can be utilised to enable some reasonable estimates of local subprime credit use and cost to be made for local authority areas, as detailed in the case study below.

An overview methodology for estimating local subprime credit use is provided in Appendix 2.

Case study: London Borough of Barking and Dagenham (LBBD)

As part of their options appraisal to improve residents’ access to affordable and responsible financial services, LBBD, with support from the Financial Inclusion Centre, undertook an analysis of subprime credit use across the borough, using some of the available FCA data. This analysis suggested that there are approximately 6,000 annual users of high-cost credit across Barking and Dagenham, accessing approximately 20,000 loans at a total value of over £9.6 million. Whilst these figures are estimates, they are conservative given the exclusion of other non-mainstream credit sources, including illegal money lenders. Additionally, due to high interest rates, the total amount repaid is estimated to be approximately £16.7 million. These figures formed a key part of the evidence base underpinning the proposal to develop a new community banking service for the borough, which was recently approved by the council’s cabinet for launch during 2021.

Illegal money lending

Illegal money lenders (or loan sharks) are lenders who aren’t authorised by the FCA and are therefore breaking the law. They often charge very high interest rates and commonly threaten violence or take away credit cards or valuables to collect repayments.

Understanding the true scale of loan shark activity, both nationally and locally, is extremely difficult. However, the national Illegal Money Lending Team estimate that 310,000 people are in debt to illegal money lenders in the UK, but warn of increased loan shark activity due to financial pressure and hardship resulting from COVID-19.

Subprime borrower profiles

The typical customer profiles for subprime credit, together with the profile of loan shark victims provided by the Illegal Money Lending team, are summarised in the table below. The full profiles are available in Appendix 3.

|

|

High-Cost Short Term Credit |

Home Collected Credit |

Rent to Own |

Pawnbroker |

Illegal Money Lending |

|

Gender (typical) |

Male |

Female |

Female |

Female |

Male |

|

Median Average Age |

32 |

42 |

36 |

39 |

35-54 |

|

Employment status |

Working (F/P time) |

Unemployed |

Unemployed |

Unemployed |

Unemployed |

|

Median Income (Net) |

£20,000 |

£15,500 |

£16,100 |

£15,000 |

Under £15,000 |

|

Housing tenure |

Rented |

Socially rented |

Rented |

Socially rented |

Socially rented |

|

Credit score |

Fair/poor |

Poor / Very Poor |

Very Poor |

Very Poor |

Poor / Very Poor |

Comparing this profile data against local socio-economic and demographic data, provides another option of identifying whether local communities are likely to be susceptible to subprime lending and/or the target of loan sharks.

Key considerations

Local approaches to the provision of affordable credit should be evidence-based and built on a robust and detailed understanding of the needs of the local community. This is vital to maximising the effectiveness and value of local delivery, ensuring its scale meets local needs and that it can be targeted to those who need it the most.

Building a holistic evidence base that includes modelling of the potential scale and cost of existing high-cost credit use will enable senior management and elected members to make informed decisions about investment in local affordable finance provision.

4. Building a business case

This section summarises relevant evidence, good practice and learning in relation to building an internal business case to secure wider council support or investment in local affordable credit provision. As budgets become tighter, but demand for support increases, it is critical that the strategic fit, cost-effectiveness and value of new services or initiatives can be easily demonstrated. This is considered particularly true for preventative services, such as the provision of affordable credit, where it can be difficult to quantify or convey the real and tangible impact that such provision can have in terms of supporting council priorities.

A template structure for a business case is identified, alongside other resources, that can be used to help to review and set out the costs and benefits.

Building a business case

The key requirements for a robust business case are detailed in the table below, alongside reference to the relevant sections within this guide, where applicable. Ensuring that any business case or proposal document contains quantifiable evidence or data, or robust and well-developed estimations, particularly as regards the need and demand and anticipated scale of outputs, impacts and value, is considered critical.

Key requirements

- Evidence of need and demand

- Strategic fit with council priorities and work streams (section 5) and relevant wider policies and strategies

- Review of existing credit use and provision, including subprime (section 3.4) and existing affordable provision

- Options analysis to extend / improve affordable credit delivery

- Potential resource implications

- Forecasted outputs, impacts and social value – including ratio of investment spend to project value (section 9)

Reviewing existing affordable credit provision

Alongside building up a picture of subprime credit use, it can also be useful to understand the scope of any existing affordable credit provision across local communities, to help identify the scale of the gap between supply and demand.

Whilst this data isn’t routinely published, councils can engage with their local community finance providers, to understand what data might be available for their local areas, at what level (e.g. postcode, LSOA) and in what format.

Examples of data disclosure

Fair Finance is a social business offering a range of financial products and services designed to meet the needs of people and businesses that are financially excluded. They are committed to being transparent in terms of their lending activity, providing details of all the loans they have made across UK postcode districts since 2005 via an interactive map on their website. They are also keen to support other lenders to develop a similar transparent and accountable approach.

Responsible Finance

Responsible Finance is the voice of the responsible finance industry, working to increase access to fair and affordable finance. They have produced some initial personal lending maps for the Greater Manchester and Birmingham/West Midlands regions, detailing the level of lending by responsible finance providers during 2017/18 against geographies of deprivation.

Invest to save

Alongside the financial savings and benefits provided to individuals, supporting the provision of affordable credit can also deliver direct cost savings to councils. A business case can therefore be made that an initial investment to support the delivery of affordable credit can ultimately help to reduce council service costs.

Case study: London Borough of Lewisham - Homeless prevention

To help support some of the most vulnerable residents in their community, the London Borough of Lewisham (LBL) partnered with Lewisham Plus Credit Union (LPCU) to provide a homeless prevention loan scheme that saved over 300 families from eviction. LBL made an initial £85,000 available to underwrite the provision of 0% interest loans, which increased to a total of £236,670 as repayments were recycled. These loans went to those tenants most at risk of eviction, to help clear their rent debt and thus maintain their tenancy. Having helped to address their short-term problems, the scheme also opened access to affordable loans and savings facilities for the tenants, helping them to save, establish a credit record and build their financial resilience and wellbeing.

Additionally, LBL benefited significantly from both initial and ongoing reductions in the costs of the evictions of families that would have otherwise taken place. They evidenced that had these families become homeless, the cost to the authority of providing temporary accommodation would have been in the region of £1.1million, representing a saving to LBL of £1 million.

A detailed evaluation of the scheme can be accessed via this link.

Developing new affordable credit provision

The following case studies highlight examples of how councils have helped to strategically grow the provision of affordable finance within their communities.

Case study: Preston City Council: Growing community finance

Lancashire Community Finance (LCF) is a CDFI providing personal loans, business loans, start-up loans and home improvement loans to individuals and businesses throughout Lancashire, alongside financial education and money and debt advice services. Preston City Council (PCC) was instrumental in the feasibility study and development of LCF back in 2005 and still retain shares and a place on the board, occupied by an elected member. In the early days of LCF, PCC grant funded small capital pots and revenue subsidies to deliver low value bespoke personal and enterprise loans across the city.

More recently they provided LCF annual revenue funding in support of their Financial Inclusion Strategy as well as the capital and a revenue fixed fee to deliver home improvement loans to owner occupiers unable to access mainstream finance, to repair their properties and/or bring them up to the decent home standard.

Case study: A Consortium approach: Falkirk, Fife and West Lothian Councils

Tackling poverty and improving outcomes for households on low incomes is a key priority for Falkirk, Fife and West Lothian councils. This leads to them agreeing to form a consortium to plan, develop and invest in a Community Finance Development Institution (CDFI) for their region. The Consortium model for developing a CDFI is the first initiative of its kind in Scotland, providing more than 700,000 residents with access to affordable finance. It enables vulnerable borrowers across the three council areas to access loan finance and divert away from high-cost credit providers. This improves the economic position of local households and communities by increasing the resources that are available for individuals to spend.

Falkirk Council led the procurement and management of IS4 Consultants in May 2015 to undertake an initial feasibility study. West Lothian Council took responsibility for continued engagement with the consultant in relation to the findings from the study. Fife Council supported the development of a detailed business case and took charge of the procurement process needed to contract a loans provider.

Following a competitive tendering exercise, Five Lamps (trading in Scotland as Conduit Scotland) was appointed as the social lender and the new service launched in 2017, providing £500,000 of affordable lending during its first year. You can download an evaluation of Conduit Scotland's service.

Key considerations

Calls for support or pitches for investment should be underpinned by a quantifiable business case, that includes a clear illustration of the impact and value it will generate and the return on investment that will be provided for residents, the council and wider community.

Alongside building up a picture of subprime credit use, it can also be useful to understand the scope of any existing affordable credit provision across local communities, to help identify the scale of the gap between supply and demand. Whilst this data isn’t routinely published, councils can engage with local affordable lenders to understand what data might be available for their local areas and to discuss potential data sharing opportunities.

5. Working with community lenders

This section summarises relevant evidence, good practice and learning on how councils can practically work with community lenders to develop and deliver, or enhance, provision of local services.

Credit unions and CDFIs

Credit Unions are financial co-operatives, providing a range of products and services to their members, including savings, loans and transnational banking.

- 283 credit unions in GB

- 1.24 million credit union members

- £969m total loans on balance sheet

Trade bodies

Find a Credit Union

www.findyourcreditunion.co.uk/find-your-credit-union

Community Development Finance Institutions (CDFIs)

CDFIs provide loans and support to people, businesses and social enterprises who find it hard to access finance from mainstream sources.

- 10 CDFIs with personal loans in GB

- 56,000 loan recipients

- £25.8m total loans

Trade body

Find a CDFI

www.findingfinance.org.uk/my-nearest-lender

There are several differences between credit unions and CDFIs which means they can provide a complementary, rather than competitive, service. Because CDFIs do not have an interest rate cap, they are able to price their loans to serve a riskier customer base than even credit unions are unable to lend to. By working in partnership, credit unions and CDFIs can therefore provide widespread and seamless access to affordable finance and thus a comprehensive and robust alternative to high-cost lending. The case study below is an example of a credit union that set up a sister CDFI, to serve the customers it could not offer loans to and prevent them falling into the hands of high-cost lenders.

Case study: Leeds Credit Union and Headrow Money Line

Leeds Credit Union (LCU) is the largest community-based credit union with over 35,000 members from Leeds, Wakefield, Craven and Harrogate. Currently, regulations governing credit unions caps the loan interest rate that can be charged at 3% per month (42.6% APR). This means that it can be more difficult to lend to those that are higher risk because they cannot price the risk appropriately.

In response, with a high-cost credit market in Leeds worth an estimated £90 million, LCU, supported by Leeds City Council’s financial inclusion programme, helped to launch a partner CDFI called Headrow Money Line (HML) to provide an affordable alternative to this high-cost provision for those declined by the credit union.

This unique partnership enables LCU to refer those loan applicants it would normally be forced to decline to this alternative source of affordable credit (charging between 69% - 99% APR). Customers continue to save and access additional financial services with the credit union but do not resort to high-cost subprime credit. Additionally, the HML loan enables customers to demonstrate their credit worthiness, and ability to repay and build their credit score, thus presenting a route towards potential borrowing from the credit union at lower interest rates in the future.

Ensuring good quality provision

Affordable Credit Code of Practice

Working with stakeholders, Fair4all Finance have produced an Affordable Credit Code of Practice that identifies best practice characteristics in affordable credit provision, across five key themes:

- organisational set-up and social purpose

- approach to customers

- lending

- repayment and recovery

- customer support and wrap-around services.

Fair4all Finance intend that all the organisations they work with will strive towards following the code of practice, to help people in vulnerable circumstances improve their financial resilience and wellbeing.

The code of practice should therefore be utilised by councils to inform any partnership work, or future commissioning exercises, with credit unions or CDFIs to ensure the quality and standard of local affordable credit provision.

Fairbanking Mark

The Fairbanking Mark is the only financial certification scheme in the UK granted accreditation by the UK Accreditation Service (UKAS). It provides robust, objective evidence to consumers and society that providers are delivering customer financial wellbeing in their products. Several credit unions have achieved the mark for their loan and saving products.

Supporting community finance providers

Targeted financial support

Councils can award grant or financial support to community finance providers to support their role and function within the local community. This finance could be used to support specific initiatives or lending activity, for example the underwriting of higher-risk lending for residents in more vulnerable circumstances.

Subordinated debt or deferred shares

Investing in community finance capital can enable affordable providers to expand the scope and scale of their local lending. These types of investment may be of particular interest because they can be treated as an asset on the council’s balance sheet. This might be more attractive than issuing a grant or other form of financial support, given the financial pressure that councils are under.

Depositing funds

Credit unions are fully regulated deposit takers, and are therefore eligible to accept deposits as banks do. Councils can therefore include credit unions within their investment portfolios and provide funding which the credit union can lend to local residents.

Business rates relief

Many councils grant discretionary business rates relief to community finance providers to take away a key expense and thereby boost their profitability.

Dedicated payroll schemes

Councils can support a credit union’s wider financial sustainability by making their payroll available to take payments towards savings and loans, thereby giving credit unions access to a new, more profitable membership base. This benefits council staff by making an ethical and responsible service available but also the credit union by helping them reach a wider range of people.

Encouraging community finance provision through procurement

Councils can use their procurement procedures to embed support for community finance providers within their supply chain. Prospective suppliers bidding for council contracts could be encouraged to outline how they would support local provision and promote relevant services to their staff (as part of their social value commitment).

Support for premises

Councils are often major landlords in their local areas, with the potential capacity to make available commercial space at low or nil rent. Many councils also have community access points or facilities that could be utilised by community finance providers to support the delivery of face-to-face services in local neighbourhoods.

Case study: Enterprise Credit Union and Knowsley MBC

Enterprise Credit Union (ECU) has over 24,000 members across three local council areas: Liverpool, Knowsley and St Helens. All three councils provide corporate support to ECU, but, in particular, Knowsley MBC provide a coordinated support package that includes:

- full business rates relief on four ECU offices in the borough

- an investment of £50,000 in deferred shares

- corporate membership of ECU with over £130,000 invested

- payroll scheme for all KMBC staff.

Further details can be accessed via this link.

Case study: Leeds City Council

Leeds City Council support Leeds Credit Union to deliver services across the city, by providing suitable space within five of the council’s Community Hubs, all located within the areas of greatest deprivation. Across these 5 hubs, LCU offer full cash services, providing much needed face-to-face delivery directly within the community, particularly for some of those in the most vulnerable circumstances.

Case study: Bristol City Council

In 2019, Bristol City Council made a £500k investment in Bristol Credit Union (BCU) to support the long-term, sustainable growth of the credit union, whilst also providing the council with financial return. This investment will enable BCU to triple in size over the next 5 years, through investment in growth, including providing affordable loans, creating jobs in the local ethical finance sector, and enabling outreach workers in the most deprived wards in the city. BCU were supported by Bristol and Bath Regional Capital CIC (BBRC), a Bristol-based impact investor, who helped BCU to design an investment that would create social impact for Bristol and provide an attractive proposition for the council. Further detail can be accessed via this link.

Case study: Bradford MDC and Bradford and District Credit Union

As part of the response to COVID-19, BMDC and BCU working in partnership as part of a council-led Covid taskforce, launched a pilot loans scheme aimed at furloughed or redundant workers. The council made £30k available to underwrite the provision of 0% interest loans to 55 residents. The maximum amount provided was £500, which was a mix of a £50 ‘saving starter’ grant and £450 loan, to be repaid once the resident was back in work or on benefits. Repayments have since been recycled into additional loans.

Case study: Scotcash and Glasgow City Council

Scotcash was formed in January 2007 as an outcome of Glasgow City Council’s financial inclusion strategy and, principally, as a response to the high levels of doorstep lending taking place in the city. It began as a partnership between Glasgow Housing Association and Glasgow City Council who, along with the Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS), the Scottish Government and Communities Scotland, provided a mixture of initial funding and support.

Since then, the CDFI has sustained its partnership with Glasgow City Council and worked to expandits services for Glasgow residents. It promotes Scotcash to local communities through direct referrals, newsletters, and through its strategic partnerships. In addition, it directly refers people that itcannot help through its Scottish Welfare Fund to Scotcash. It also refers grant recipients who do not have bank accounts to Scotcash so the CDFI can assist them to open these for the grant to then be paid into.

Supporting council service delivery

Affordable and responsible credit provision can also be tailored by local lenders to directly support council service delivery and local area priorities as detailed by the case studies below.

Case study: Private Sector Rent Deposit Scheme

In conjunction with HertSavers Credit Union, East Hertfordshire District Council operate a private sector rent deposit scheme to house people in the private rented sector and prevent homelessness. Via interest-free loans from the credit union, the council can advance a deposit and rent in advance to accepted residents who are on a low-income or benefits. Further detail can be accessed via this link.

Case study: Home Improvement Loans

Since 2010 Street (UK) Homes (Street UK) has worked with local authorities to enable low-income homeowners to access affordable credit for essential home improvements, bringing their properties up to the Government’s Decent Homes Standard. Over ten years, Street UK has helped over 3,500 homeowners invest £31 million in their homes, improving health outcomes and reducing energy costs.

Case study: No-Interest Loans to support vulnerable residents

Street (UK) Homes (ESCU) runs four interest-free loan schemes, in partnership with various charities in Brighton & Hove, aimed at supporting residents in vulnerable circumstances. This includes the provision of loans for rent deposits and rent in advance to help homeless people secure accommodation in the private-rented sector, and support for people who have been through the asylum system and those with no recourse to public funds.

Case study: Homeowner loans in partnership with Councils in the South West

Operating for 16 years Lendology CIC works with 18 council partners to enable homeowners to access a range of loans for improving, adapting, and enhancing their properties, including owners of empty properties. In 2019/20, it lent £1.7 million that helped bring 14 properties back into habitation and improved the housing conditions for 459 people.

Further practical guidance can be found in the following reports:

- Credit Unions and Local Government: Working in Partnership – by Association of British Credit Unions (ABCUL) and The Co-operative Party.

- Good credit project: A toolkit to build local financial resilience – by Demos

Council arrears

A number of social sector tenants already use their rent payments as an informal method of addressing financial shortfalls at certain points of the year and to manage debts or unexpected bills. By accumulating arrears, it provides a short-term alternative to resorting to high-cost credit but without proper structure or procedures, it can result in formal arrears actions that can risk their tenancy and create pressures for councils and landlords.

Rent Flex as an alternative to high-cost credit

Developed by the Centre for Responsible Credit, Rent Flex provides a formal mechanism for tenants to tailor their rent payments in line with likely financial pressure points over the year. By encouraging residents to reduce their use of credit by planning ahead, it is intended to build resilience through savings and improve financial wellbeing.

Developing an integrated approach

It is important to remember that the provision of affordable credit should be part of a broader package of advice and wrap-around support interventions, such as money and debt advice, offered by councils and local partners.

Ensuring these are aligned to affordable credit is essential to not only maximising finite resources and providing financial help to the most vulnerable, but also for converting this short-term remedy into longer-term financial stability, by addressing the household’s wider and underlying problems. Some specific actions that councils are well placed to support local affordable lenders to deliver include:

- providing support for customers to build their financial resilience, either in-house or through partnerships or referrals. This should include encouraging savings behaviour (see section 6.2.1 below), building financial capability and helping customers to access their full entitlement to grants and benefits

- providing customers who are declined for credit with information as to why the decision has been taken, alongside signposting to relevant guidance, support or alternatives

- working in partnership with local or national free debt advice providers, maintaining an active channel to refer customers to when they are identified as having financial difficulties either at the application stage, and therefore declined, or whilst they are an active customer.

Key considerations

Councils should consider investing in credit unions via subordinated debt or deferred shares. Given the financial pressure on councils, investing in credit union capital can allow credit unions to expand their operations while retaining the investment as an asset on the council’s budget sheet, which may present a more attractive funding proposition than a grant.

Affordable lenders can often provide flexible and tailored products to meet the different needs of partner organisations. Councils should therefore identify how affordable finance products could be best used to support cost-effective council service delivery, and engage with local providers to discuss potential product development opportunities.

Ensuring that affordable finance provision is robustly integrated with wider support services, including those of the council and local voluntary and community sector partners, should be a key underlying principle to convert short-term support into longer-term financial stability by addressing wider circumstances and needs. Given their leadership role within local communities, councils are well placed to ensure that the right partnerships are in place to facilitate this coordinated approach.

Through their engagement with, and support of, affordable lenders, councils should encourage and facilitate the adoption of the Affordable Credit Code of Practice as necessary. Additionally, the criteria highlighted within the code could be used to inform future commissioning / contracting processes for affordable finance provision, to ensure the quality and effectiveness of local services.

6. Promotion and awareness raising

A key factor in the decision to take out high‐cost credit is often the ease and availability of online lending with immediate decisions together with a lack of awareness about more affordable alternatives. Consumer awareness of credit unions and CDFIs is relatively low, especially when compared to many high‐cost lenders. This section therefore summarises relevant evidence and resources to support the effective promotion and awareness raising of affordable finance, to help divert residents away from high-cost lenders and towards alternative and more appropriate sources of support.

The legal framework for promoting affordable finance

Credit-related activity, including credit broking (the introduction and referral of individuals to sources of credit) is a regulated activity, that is usually likely to require authorisation by the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA).

Importantly, local authorities are specifically excluded from the legal requirement to be authorised for most credit-related regulated activities, including credit broking, as detailed in the FCA’s Perimeter Guidance: PERG 2.9.23G.

Those authorities that provide social housing, however, may find the following FCA guidance note of interest: FG18/6: Helping tenants find alternatives to high-cost credit and what this means for social housing landlords.

This document aims to help social housing landlords, including local authorities and housing associations understand the scope and application of consumer credit regulation when they help tenants to find alternatives to high-cost credit, such as loans from credit unions or CDFI’s. The FCA recognise that social landlords can play a key role in this area, helping to create better options for consumers that could provide them with a cheaper, lower-risk source of finance. In recognition of this context, in July 2019 the law introduced an important exclusion for social housing landlords from the scope of credit broking. It is important to note, however, that this exclusion only applies where:

- the activity concerned is affecting an introduction of an individual who wishes to enter into a credit agreement

- the introduction is to a credit union, community benefit society, registered charity (or subsidiary of a registered charity), community interest company limited by guarantee or subsidiary of an RSL, and

- the introduction is provided fee free, i.e. the RSL receives no fee (which includes money or any other financial consideration).

The guidance note can be accessed via this link, and any enquiries can be made to the FCA’s dedicated social housing team via: [email protected].

The importance of promoting affordable finance

The direct promotion and marketing of local affordable finance provision is critical to diverting residents away from high-cost lenders. Unfortunately, the services available via credit unions or CDFIs can often struggle to be heard against these high-cost lenders, backed by significant marketing budgets and a highly visible digital and media presence. Additionally, for many of those in vulnerable circumstances who are looking at credit options, it can be hard to see beyond the weekly cost that is often the focus of advertising, and to recognise the longer-term financial implications of high-cost credit. Research by the Centre for Responsible Credit on behalf of Fair For You, evidenced that before finding their way to Fair for You, 80% of their customers had borrowed from other sources in the previous 12 months, including 36% from doorstep lenders and 29% from the rent-to-own sector.

Save as you borrow

Beyond the direct financial benefit provided by paying less interest, compared to higher-cost borrowing, the effective promotion of affordable lending also provides a gateway to other affordable and responsible financial services and is often the critical ‘hook’ that can be used to initially catch consumer attention. “Save as you borrow” (SAYB) is the practice of credit unions to encourage their members to make savings contributions as part of their regular loan repayments – as illustrated by the example below, from London Mutual Credit Union.

As evidenced by the Fairbanking Foundation, the SAYB model of lending helps to build savings habits and thus financial resilience. With its ease, the savings provide security and the lump sum at the end of the loan and the sense of achievement, all or which are beneficial to the customer.

For those who have rarely or never saved, the well-being benefits are tangible – as most are motivated to continue the painless practice they have begun. It identified that 26% of participants who accessed a SAYB product, were saving regularly before they borrowed, but an additional 45% stated they would sustain their new savings habit in the future.

Recommendations for local authorities

The promotion of affordable and responsible finance by local authorities is also advocated by the FCA. In their Alternatives to High-Cost Credit Report, the FCA note that local authorities sit at the centre of their community and have a key role in promoting economic growth in their area.

Additionally, they highlight that given their responsibility for essential and support services, they are in a unique position to communicate with and signpost consumers to relevant services. The report therefore outlines a number of recommendations relevant to local authorities on promotion and awareness-raising of affordable and responsible credit:

- Local authorities and other frontline service providers, such as RSL’s and relevant charities, should consider providing their service users with information about affordable lending alternatives, embedded within their regular service delivery.

- A lot of the existing information about lower-cost credit options could be made more prominent and accessible, particularly online. The most accessible webpages are those that can be easily found from the homepage, for example via clear menus or headings such as ‘Help with your borrowing’ or ‘Getting the best deal on loans’.

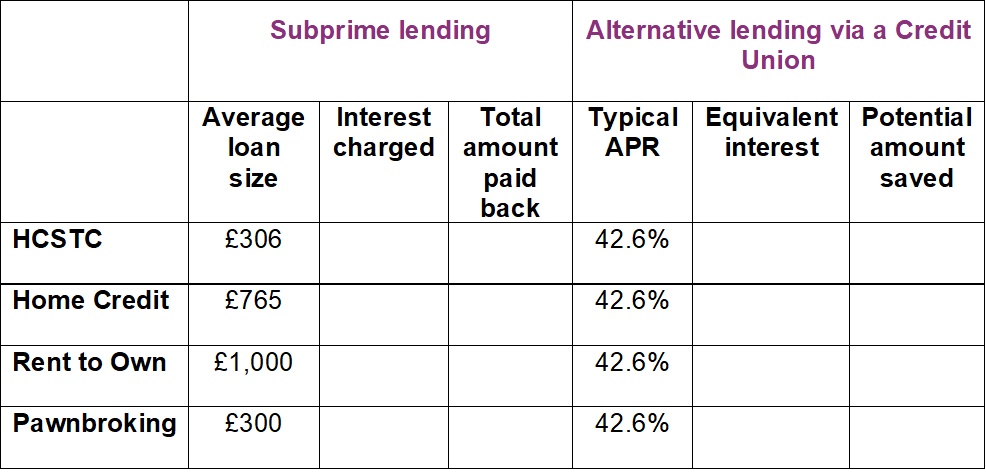

- The quality of signposting of helpful information about the characteristics of credit union and CDFI loans could be improved by including illustrative and interactive information to increase consumer awareness of lower cost borrowing options – as per the table below.

- Alongside promotion of affordable lending options, consumers should also be signposted to additional sources of further information and support, such as the Money and Pensions Advice website.

Promoting lending and interest rates

There is often a negative public perception about the interest rates charged by community finance providers and concern about actively promoting such loans, particularly when they are compared against mainstream borrowing options, such as bank credit cards and loans. It is important to recognise, however, that many people are unable to access this lower-cost credit as they are financially vulnerable, on low or unstable incomes or have a bad credit history. Many vulnerable, low-income households with a legitimate need for credit, to cover income gaps or emergency expenses for example, therefore access high-cost credit (such as doorstep or payday loans) because they do not have, or perceive that they do not have, any other alternative.

In addition, there is also a social cost to households accessing subprime credit. For example, nearly two thirds (60%) of Fair For You customers who had previously borrowed from other higher-cost sources reported that this borrowing had created significant difficulties for them – 36% said it had led to stress or anxiety about money, 32% that their credit score had suffered and 23% had to cut back on essential spending to make the repayments.

As the table below illustrates, this borrowing is significantly more expensive than that offered by community finance providers, who also provide wraparound support to build financial stability and resilience.

Borrowing £400 over 6 months / 26 weeks

| London Mutual Credit Union | Conduit | Provident | Satsuma Loans | Mr Lender | |

|

Type of lender |

Credit Union |

CDFI |

Home credit |

HCSTC |

HCSTC |

|

Representative rate (APR) |

42.6% |

99.8% |

535% |

*not provided |

1,242% |

|

Amount of interest |

£43 |

£87 |

£436 |

£358 |

£364 |

|

Total repayable |

£443 |

£487 |

£624 |

£758 |

£764 |

Source: Price quotes taken from company websites on 23 March 2021. For exact quotes please refer to the company websites.

Partnership approaches

Marketing is identified as the top barrier to growth by affordable credit providers. However, given their role as local leaders and partnership co-ordinators, councils are well placed to help affordable lenders to develop and deliver comprehensive, sustained promotional campaigns that amplify their message and help to reach new audiences.

Good credit project: Sheffield City Region

In the run-up to Christmas, the Good Credit project ran a public campaign across various channels to promote access to affordable credit within South Yorkshire – directing people to the project website with listing of affordable credit providers. As a result, Sheffield Credit Union made 37% more loans in December 2019 compared to December 2018 – Good Credit Index.

Hull Money

Hull Money was established in 2018 by CDFI Five Lamps in partnership with Hull City Council, advice agencies and other local organisations. It provides a single branded gateway for customers when they need local financial services including savings, loans, white goods and advice. The online hub links customers directly to their provider of choice, which in terms of affordable lending includes both Hull and East Yorkshire Credit Union and CDFI Conduit.

Our Newham Money

Our Newham Money adopts a similar approach to Hull Money (and Northumberland Money) offering a single portal for coordinated financial support and services for residents in the London Borough of Newham.

The service is run by Newham Council, who work in partnership with London Community Credit Union to provide easy and straightforward access to affordable and responsible credit.

Effective communication and engagement

Research on the behavioural and psychological impacts of poverty highlights the detriment that financial worries, poverty and being in vulnerable situations can have on decision making and the ability to take positive action. Poverty has significant cognitive and psychological aspects, eroding self-esteem and self-confidence and generating feelings of helplessness and fear of dependence. Research has evidenced that when people on lower incomes suffer from financial pressure, the drop in their cognitive function is equivalent to an entire night’s sleep.

The table below therefore highlights some useful resources to support effective communication and engagement, within this context, across advice and support services, including the provision of affordable credit.

|

Poverty and decision making: how behavioural science can improve opportunity in the UK |

This research report by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation highlights the impact that financial worries, poverty and being in vulnerable situations can have on decision making and the ability to take positive action. |

|

Better Money Behaviours

|

The London Housing Financial Inclusion Group sponsored report, Better Money Behaviours, provides a behaviour change toolkit for engaging people on money issues – the toolkit outlines 12 principles for effective engagement. |

|

The EAST framework |

The Behavioural Insight Team has developed a simple framework to help organisations to deliver effective behavioural approaches. In their report, they have identified four simple principles (Easy, Attractive, Social and Timely – EAST) to encourage positive behaviour change, that can be adopted and implemented across the delivery of activity to tackle financial hardship. |

Key considerations

Promotional and awareness raising activity should be informed by relevant behavioural insights research and resources to ensure that it is as engaging and effective as possible. Activity should be targeted to ensure that those most in need can find out about the support available and this should include the use of partners working with vulnerable residents.

Practical opportunities to embed relevant information, resources and support tools across council activity and processes should be mapped out and prioritised. For example, embedding reference to local affordable finance provision and the ‘stop the loan sharks’ team within relevant council tax communication processes. External resources and tools can also be used to add value to local information.

7. Monitoring and impact measurement

The socio-economic benefits for an individual improving their financial resilience and wellbeing by accessing affordable and responsible finance are diverse and differ based on every individual’s circumstances. This could be everything from the money saved from borrowing more affordably to reduced financial stress and improved health outcomes. This section therefore sets out a clear framework and methodology to monitor and measure the holistic impact and value of supporting the provision of affordable finance, in relation to individual wellbeing, social value and local economic impact.

Measuring social value – methodology

The methodology to measure the holistic social value of affordable credit provision focuses on four key areas, as highlighted below:

- key deliverables/outputs

- financial gains for households

- impact on health and wellbeing, and

- additional economic multiplier effect.

Key deliverables/outputs

|

Total number of loans |

No. |

|

Total value of lending |

£ |

|

Value of higher risk loan book (diverted from subprime) |

£ |

This data can be used to evidence a cost per output of the investment into affordable credit provision.

Financial gains for households

Access to affordable credit delivers significant benefits and cost savings to individuals and households, particularly for those on the lowest incomes and who are financially excluded.

|

Number of affordable loans (diverted from subprime) |

No. |

|

Estimated cost saving to households – the amount saved through lower-interest loan repayments |

£ |

This data can be used to identify a ratio of investment to financial gains – e.g. each £1 of investment creates £X of financial gains for local residents.

Impact on health and wellbeing

Wellbeing Valuation has been accepted as a robust and rigorous method of measuring wellbeing value. This approach allows organisations to measure the success of social interventions by analysing how much they increase people’s wellbeing. To do this, the results of large national surveys are analysed to isolate the effect of a particular factor on a person’s wellbeing. Analysis then reveals the equivalent amount of money needed to increase someone’s wellbeing by the same amount.

The HACT Wellbeing Valuation model has a number of outcomes relevant to financial resilience and wellbeing that could be adopted to measure the impact of increasing access to affordable credit and wider financial inclusion activities, as detailed in the table below.

|

Outcome |

Description of outcome |

Average value |

|

Able to pay for housing |

In the last 12 months have you had any difficulties paying for your accommodation? |

£7,347 |

|

Financial comfort |

How well would you say you yourself are managing financially these days? |

£8,917 |

|

Relief from being heavily burdened with debt |

If you are in debt, how much of a burden is that debt? |

£10,836 |

|

Able to save regularly |

Do you save on a regular basis or just from time to time when you can? |

£2,155 |

|

Feel in control of life |

I feel that what happens to me is out of my control |

£15,894

|

This data can be used to identify a ratio of investment to social impact – e.g. each £1 of investment generates £X of social impact for local residents.

So, for example, a local resident who accesses an affordable loan from a credit union and highlights that they are now experiencing ‘relief from debt’ would generate an increase in wellbeing of £10,836. This monetary figure represents the change in wellbeing the average person feels about themselves, in terms of increased confidence, sense of control and other related benefits, because they are now able to save, due to the lower loan repayments they must make. This change feels the same as having an extra £10,836 in their pocket.

To help organisations use the tool, HACT provide a range of resources including guides, supporting materials and a social value calculator. An introduction to the approach and a detailed methodology is outlined in the HACT report: Measuring the Social Impact of Community Investment: A Guide to using the Wellbeing Valuation Approach.

Additional economic multiplier effect

There is limited available research estimating the local economic impact of improving access to affordable finance and supporting increase of financial inclusion. The most applicable return on investment research is taken from work undertaken by Circle Housing that estimated the ‘economic multiplier’ of its work with Leeds Credit Union.

This calculated the benefit of the additional funds generated from affordable loans, banking products and dividends retained and circulated within the local economy by considering how this money is spent or saved during the following year. The research estimated that for every £1 invested by Circle Housing, there was an additional £5.60 benefit to the economy.

Additionally, social impact analysis by Hoot Credit Union (see case study below), evidenced that 72% of money lent by Hoot is spent locally in Bolton and Bury. In 2018/19, this equated to a £2 million boost to the local economy.

This data can be used to identify a ratio of investment to economic benefit – e.g. each £1 of investment generates £xx financial benefit to the local economy.

Case studies – Community lenders

Community lenders are increasingly commissioning their own social impact reports to fully demonstrate and evidence the impact and value that their delivery has on local communities and economies, as illustrated by these examples.

Clockwise Credit Union - Social Return on Investment Report

CCU serves 15,000 members across Leicestershire, Rutland, Leicester and Northamptonshire. In 2018 and 2019 CCU invested £2.4 million in delivering services to their members, the impact of which was captured through a detailed social return on investment evaluation. This evaluation evidenced a range of outcomes for members from this investment, including feeling less stressed and anxious, gaining skills and building independence, with a total value of £10.4 million.

The Owl Effect: Measuring the Social Impact of Hoot Credit Union

Hoot Credit Union has over 6,000 members in Bolton and Bury. In 2018/19, Hoot took part in a detailed social impact exercise, including survey work with over 500 members. The subsequent analysis, using the HACT calculator evidenced that Hoot’s services generated £9.5m in social value for the local community and provided a £2m boost to the local economy.

The Social Impact of Fair For You

Fair for You is a Community Interest Company providing affordable credit to families with incomes in the lower half of the income distribution throughout the UK. Since its launch in 2015, FFY has provided over 77,000 loans, worth £26 million, to more than 33,000 customers. The social impact of this lending has been detailed in a report produced by the Centre for Responsible Credit.

- FFY has generated at least £50.5 million of social value since its launch.

- Over £2 million saved from reduced use of NHS services, due to the positive health benefits of having essential home items.

- FFY has helped 71% of its customers move away from high-cost credit, realising just under £9 million of financial savings.

Key considerations

Robust impact measurement and evaluation should be embedded within the delivery of affordable finance, enabling the council and its affordable finance partner(s) to track the impact of support on residents, the council, wider community and local economy. Appropriate measures should be agreed and included in any partnership agreements or contracts, alongside the standard output-based KPIs.