What is digital citizenship?

Social media has become an important public space, a place where councillors share political information and engage with other councillors, support officers and residents. Social media has the potential to improve democracy by facilitating bigger, freer and open conversations and by allowing representatives to communicate directly with citizens. But it also opens the door for abuse, harassment and intimidation, along with the swift spread of mis and disinformation that can impact local democracy.

The UK Government’s Online Harms White Paper defines disinformation as the spread of false information to deceive deliberately. Misinformation is referred to as the inadvertent sharing of false information. Both can refer to false information about a policy or an issue (eg, misleading or false information about COVID-19) or the spread of rumours about a person (this includes, for example, character assassination).

Online harassment, intimidation and abuse, and the spread of mis and disinformation, are now major challenges to local democracy. They undermine productive engagement between candidates or elected officials and citizens, exacerbate distrust and polarisation in politics, and present further barriers to political participation. With those from under-represented groups reporting disproportionate levels of both online and offline abuse and intimidation, this represents a challenge to increasing the diversity of our local representatives.

Due to its pervasive nature and wide reach, the harassment, abuse and intimidation of individuals in public life are attracting attention in the UK and worldwide. National and international efforts have been made to improve police training and increase awareness and protection. But the majority of initiatives deal with the abuse once it has already occurred. Meanwhile, the nature and far-reaching consequences of harassment and intimidation demand a different approach; one that is preventive, proactive and positive.

Improving digital citizenship is a key element of the civility in public life work by the Local Government Association (LGA), Welsh Local Government Association, Convention of Scottish Local Authorities (COSLA) and Northern Ireland Local Government Association (NILGA), and is becoming increasingly important as our online interactions grow and as new information technologies are becoming major forms in which citizens, councillors and officials communicate.

Digital citizenship is about engaging in appropriate and responsible behaviour when using technology and encouraging others to do so as well. It encompasses digital literacy, ethics, etiquette, online safety, norms, rights, culture and more.

Developing digital citizenship requires us to improve online political communications. It is about expressing our opinions while respecting others’ rights and personas and avoiding putting them at risk or causing unnecessary distress. It is about respecting freedom of speech and disagreement while condemning abuse.

This guide outlines research in relation to councillors and digital citizenship, and looks at the good work going on in the UK and abroad. It’s partner publication “Practical Advice for Councillors”, provides advice and resources for councillors.

What is online harassment and intimidation?

The LGA and WLGA Councillors’ Guide to Handling Intimidation defines public intimidation as “words and/or behaviour intended or likely to block, influence or deter participation in public debate, causing alarm or distress which could lead to an individual wanting to withdraw from public life”. This includes discriminatory, physical, psychological and verbal actions such as physical attacks; being stalked, followed or loitered around; threats of harm; distribution of misinformation; character assassination; inappropriate emails, letters, phone calls and communications on social media; sexual harassment or sexual assault; and other threatening behaviour.

Specifically, online harassment is defined as “a form of abuse or intimidation facilitated by technologies of information”. It is characterised by online communications that shut down, intimidate, or silence people, often through expressions of disrespect towards individuals and groups. Online harassment can range from dismissive insults to racial slurs to threats of physical, psychological or economic violence, hate speech, intimidation and abuse. Unlike certain other types of online violence such as youth cyber-bullying and cyber-racism that have received considerable public interest, online harassment, abuse and intimidation against politicians have, until recently, received limited attention.

Why is it important?

While it is often dismissed because of its virtual nature, online harassment can be as harmful as other forms of abuse and violence that happen offline. Online abuse has significant psychological consequences, inflicting serious emotional harm on victims. A large proportion of elected officials in the UK experience anxiety or fear resulting from experiences of harassment and intimidation, potentially impacting the behaviour and political ambitions of councillors and potential councillors, especially those from underrepresented groups.

Additionally, the very nature of social media means that the abuse received by political actors is not limited to the public space. It travels to the private sphere when it is received by the victim at home or in another place that previously felt safe. Recent research has shown that victims of online harassment are also more likely to experience other forms of abuse and that its effects on wellbeing are as serious as those resulting from offline and explicit forms of violence.

The political objective of online harassment is often to intimidate, shame, discredit or influence politicians and politics. Effective strategies to mitigate or combat online harassment should consider whether the person being harassed knows the harasser or not, the number of victims and perpetrators, whether it happens across different platforms or just one and whether the harassment also happens offline.

Online harassment represents an important challenge for local politics as it erodes a sense of community. Councillors live amongst members of their community and need to interact with them to ensure that they represent residents effectively. When they are victims of online harassment and intimidation because they participate in local politics, they can see their interactions with neighbours and friends severed, increasing feelings of isolation and a lack of engagement with the community.

Online harassment and intimidation threaten democracy as the fear of becoming a victim can demotivate individuals from standing for election and undermine institutional efforts to encourage individuals from underrepresented groups to stand for office.

Online harassment and intimidation, including smear campaigns, damage the quality of the political discussion. It is very time and energy consuming for councillors to deal with abuse on social media, especially as it tends to occur simultaneously on different platforms such as Twitter or Facebook, and also over email. Thus, dealing with online abuse can easily become an overwhelming activity that reduces time devoted to council activities. Additionally, fear of intimidation can prevent councillors from engaging in certain policy discussions, undermining their expertise and experience, and reducing the representation of residents. Furthermore, online abuse damages the quality of the political discussion because it is person-focused, meaning that it focuses on the characteristics, qualifications and personal lives of councillors instead of the policies promoted or the work done.

Online abuse of local councillors

One of the main problems in the study of online harassment in local politics relates to the lack of reliable data about the extent and nature of the problem. There is anecdotal evidence based on news coverage that the online abuse and intimidation of council members is becoming worse. However, the lack of systematic evidence makes it difficult to reach conclusions with regard to the most common forms of online abuse, who is being targeted and with what consequences.

To get a clear understanding of the nature of online abuse experiences by councillors, this section presents results derived from a large online survey conducted by Dr Sofia Collignon (Royal Holloway, University of London) and Dr Wolfgang R Rüdig (University of Strathclyde) between April and June 2020.

The survey was answered by 1,487 local councillors in England elected in 2019. The response rate was 17 per cent (from a total number of 8, 296 councillors contacted), of which:

• 4 per cent identified as black, Asian or minority ethnic

• 11 per cent identified as disabled.

Summary of findings

The survey asked councillors if they had suffered from any form of abuse, harassment or intimidation, according to their understanding of the terms. Thirty-four per cent of councillors explicitly identified the abuse as harassment.

The survey then presented councillors with a list of possible experiences of physical, psychological and online abuse. We observe an increase in the number of councillors that indicated they have experienced some form of inappropriate behaviour. Forty-six per cent of councillors suffered from harassment, 12 percentage points more than those who explicitly labelled their experiences as such. Together, these results indicate that there is still work to be done to inform councillors of what constitutes intimidatory behaviour and to de-normalise abuse.

Councillors reported that harassment came equally from residents who were angry about local situations or decisions, and from their fellow councillors (71 per cent in each case).

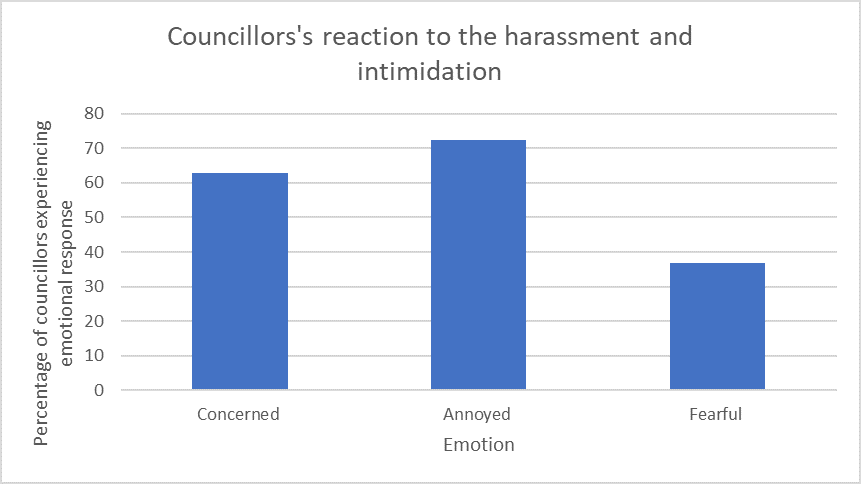

The harassment and intimidation of councillors can have strong emotional consequences which can affect councillors’ wellbeing and capacity to engage in meaningful council activities. The survey indicates that the majority of councillors were concerned (63 per cent) and annoyed (72 per cent) by the abuse received. Thirty-seven per cent of councillors experienced some fear as a result (Figure 1).

Figure one

Thirty per cent experienced harassment on social media and 28 per cent received abusive or threatening emails. Forty per cent of councillors have been on the receiving end of at least one form of technology-enabled abuse.

There is a strong significant correlation between being the victim of online abuse and feelings of security. Fifty-nine per cent of councillors who suffered online harassment have experienced some fear while performing their duties. But this can also be because abuse on social media often correlates with other forms of abuse. Twenty-five per cent of those harassed online also received threats and 12 per cent had people loitering around their homes or work.

The survey did not ask councillors specifically if they have been victims of smear campaigns or rumours. However, it included an open-ended question asking them to describe the experience that affected them the most. The qualitative analysis of this open-ended question suggests that the spread of rumours or mis and disinformation about councillors are a widespread practice and that it is extremely harmful to councillors' wellbeing and ability to perform their duties. While it is not possible at this stage to quantify the frequency of this practice, further interviews sustained with councillors corroborate these findings. Spreading of rumours for character assassination and smear campaigns were mentioned as perhaps one of the most used and damaging tools to harass and intimidate councillors.

Councillors response to abuse

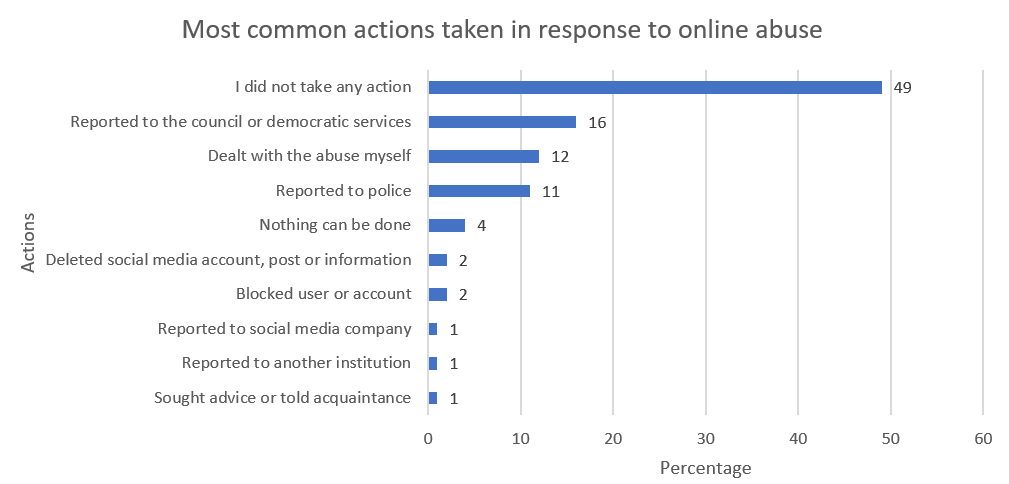

The survey asked in an open-ended question to briefly describe any action taken in response to inappropriate behaviour experienced as a councillor. Analysis (figure two) of the open-ended question shows that among councillors who have suffered online harassment, almost half did not do anything in response (49 per cent). The large proportion of councillors that decided to take no action suggests again a degree of normalisation of abuse in politics but also the perception that currently available mechanisms are not efficient or enough to deal with the problem. This is exemplified by comments made by councillors:

"None [action is taken], nothing would be done about it."

None, don't want to exacerbate the situation or rise to the threat.

"No, as it would be emotionally exhausting, highly time-consuming and not be taken seriously. My biggest concern is bullying and online abuse and harassment such as Next Door social media web site which I sadly no longer use as a result."

Figure two

Other councillors indicated that they dealt with the abuse themselves (12 per cent), successfully in some cases and unsuccessfully in others. For example, one councillor decided to withdraw from social media:

“Yes, I stood up for myself. It has happened so often I became resilient to a lot of it. I stopped using social media for a year to give myself a break - I didn't miss it but recently re-joined temporarily. Although the prolonged period and the severity of the bullying I received as a parish councillor before I became a district councillor, had a detrimental effect on my mental health I suffer from PTSD and anxiety as a result of it.”

It is important to flag here the role democratic and member services play in supporting councillors to deal with abuse, as this is the most frequent action taken in response (16 per cent).

“Spoke to democratic services and now use them as email contact and removed address from council site.”

“Consulted Democratic Services for advice.”

“I contacted democratic services at the borough to ask how to respond. On one particular occasion, they advised me to respond with an answer that suggested the question was over and above my responsibilities as a councillor. This didn't stop resident continuing with his line of enquiry.”

Phoned the police. Made sure democratic services were informed. Made sure the MO [monitoring officer] was informed if the behaviour involved a complaint. Responded directly with a calm and clear 'agree to disagree and request not to attack me personally’. In one instance, blocked an individual from my Facebook.

The next most frequent action was reporting to the police (11 per cent). The open-ended questions highlight the difficulty of getting police action. One reason frequently mentioned by participants is that the abuse does not always come from one single person, that perpetrators cannot be easily identified and the high threshold required by the police to get involved.

“Reported to the police twice when coming from a member of the public that I could identify. I reported threats by [omitted for privacy reasons] and were told by the police that it is was all part of the rough and tumble of politics."

Every time the perpetrator did something we logged and reported it on 101 eventually after he took pictures of my home from my front lawn, I reported him to the police who visited him, we installed CCTV. He continued to stalk all of my family members and fellow councillors even after that.

“Contacted police, they felt I was perhaps worrying too much”

Only a minority of councillors decided to block the accounts or to remove content. This may be because of a desire to engage with, and appear open to engagement with, residents, or a lack of understanding of the different privacy tools offered by social media platforms.

Lessons from Wales

Evidence presented to the Senedd Equality, Local Government and Communities Committee in 2019 suggest a similar picture in Wales. The Committee heard that elected representatives have experienced bullying, discrimination and harassment as part of their public lives, and that the fear of such experience is a barrier to many potential candidates. Of the councillors who participated in the committee’s survey, a quarter had experienced abuse, bullying, discrimination or harassment from within their local community; one in five (19.2 per cent) from within the council; one in ten (11.8 per cent) from within their political party or group. Only a third of councillors had not suffered such behaviour during their time in office.

The full “Diversity in Local Government” report of the committee is available online.

Lessons from the analysis of the data

The data provides key insights into the dynamics behind online harassment and intimidation of councillors. It shows that online abuse is widespread and correlates with other forms of physical and psychological abuse. The survey also shows that abuse comes from members of the public and other councillors alike and that it has emotional consequences. The analysis of the open-ended question highlights the difficulties that councillors face to effectively deal with the abuse, with a considerable proportion of them deciding to do nothing, or feeling there is nothing that can effectively be done, in response. The answers also highlight the importance of having clear and effective institutional mechanisms to deal with the abuse, and institutions that provide timely support.

The following section provides an overview of current national and international initiatives to deal with the problem of online harassment and intimidation. The section closes with the limitations of current approaches, highlighting the need to transition from reactive measures that deal with the abuse once committed to a more proactive and preventive approach.

New approaches and best practice

Current national and international practices can be broadly divided into four groups:

- IT solutions

- training

- improving police response

- platform governance and regulation.

This section describes each of them and provides some examples derived from national and international best practice.

IT solutions

In response to widespread social and political pressures to deal with online harms and online harassment, social media platforms have developed their guidelines and moderation principles. This includes the use of machine learning to automatically find threatening language. Communications identified as threatening or abusive this way will then be automatically censored or sent to human coders who can decide the best route of action: flag posts, forbid anonymous accounts and facilitate the identifications of perpetrators and the removal of content.

This approach is very practical to deal with large volumes of data. But it presents some challenges. First of all, machine learning approaches still do not efficiently deal with sarcasm or with implicit threats. The second is associated with the manner and severity in which a platform chooses to handle harassment, which varies across platforms. The lack of clarity and consistency across platforms can confuse some users. Moreover, tech companies are based in different countries with different political landscapes used by multicultural audiences. This variation means that some problematic content remains permitted while other political discussion and expressions are silenced.

It is also important to remember that social media platforms are not neutral. Their algorithms reflect social biases as well as commercial interests. Moderation is not only flagging and automatically removing content; it involves decisions that can go from down-ranking and reducing the visibility of content, putting content in “quarantine”, dereferencing content, adding a label, alert or supplementary/qualifying information, cautioning users before the publication of content or banning users from the social sphere altogether. Most tech companies still have unclear content moderation protocols and do not disclose their exact guidelines on what constitutes hate speech and harassment or how they implement those guidelines. There is widespread pressure for social media companies to be more transparent in their policies and protocols.

There is also a concern related to the commercial use of the data collected while moderating. Social media survives and thrives on user engagement, which increases incentives to manipulate users and to design algorithms that expose some of them to polarised conversations.

Social media companies have frequently made changes to their policies only when they have been forced by the attention paid by the public to major incidents. There are ethical implications that need to be addressed before transferring even more power of censorship to large corporations. Additionally, moderating and flagging large volumes of content is still a reactive approach that deals with content only after it has been read and circulated.

Good practice using technology and machine learning approaches to deal with problematic content

AretoLabs, a social enterprise has created ParityBOT, a bot that detects problematic tweets about women candidates and responds with positive messages, thus serving both as a monitoring mechanism and a counterbalancing tool. ParityBOT has been used in Canada during the federal election in 2019, and the Alberta election in 2019, in New Zealand during the 2020 national elections, and in the United States for the 2020 election.

Twitter uses AI to fight inappropriate content on its platform. In 2019 Twitter responded to the criticisms for allowing certain Tweets that violated their rules to remain on Twitter by publishing a new notice clarifying that some tweets remain available when it was considered in the public interest, even if they would otherwise violate their rules. Moving forward, they recognised a need for balance between enabling free expression, fostering accountability, and reducing the potential harm caused by these Tweets and started placing a notice screen with additional information to add context and clarity that the public has to click or tap through before seeing the Tweet. The changes apply to verified government officials, representatives or candidates for a government position who have more than 100,000 followers.

Since 2020 Twitter has also been proactive in implementing strategies to reduce the spread of mis and disinformation. They facilitate finding credible information by introducing labels and warning messages on top of Tweets containing synthetic and manipulated media or disputed or misleading information related to COVID-19. These labels link to a Twitter-curated page or external trusted source containing additional information on the claims made within the Tweet.

Training

This group of strategies include campaigns aimed to raise awareness and knowledge about online harassment as well as initiatives aimed at training individuals in public life on digital self-defence. These initiatives aim to equip people with the necessary tools to use the online tools available to them and stay safe online, for example, by blocking abusive users, use secure passwords, identify scams and use privacy settings.

Good practice in training individuals in public life on digital self-defence and raising awareness

The LGA and WLGA Councillors’ Guide to Handling Intimidation and the WLGA social media guide for councillors include strategies and tips to stay safe online and offline while in public office. Other initiatives on digital self-defence include The Cybersecurity Campaign Playbook by Harvard University and Dealing with digital threats to democracy: a toolkit to help women in public life be safer online by Glitch.

The Anti-Harassment Guidelines: A Toolkit for Commonwealth Parliamentarians is a practical guide that aims to define harassment and to tackle toxic behaviour in the workplace, online and offline. The National Democratic Institute (NDI) and Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU) global #NotTheCost campaign aimed to raise awareness, collect information, and augment capacity among partners on violence against women in politics while building consensus and collaboration across stakeholders to define the issue clearly, improve data collection for better advocacy and find alternatives to stop it.

The German government, in collaboration with the Körber-Stiftung foundation and the main organisations of local authorities in Germany, launched this year a website dedicated to providing information and assistance to local politicians who are experiencing harassment, threats or any form of violence. The website is a hub of information on politicians’ rights and obligations, preventive measures and good digital practice to deal with abuse.

Sweden has taken important approaches to prevent the spread of mis and disinformation. In 2018, the Swedish Civil Contingencies Agency updated its public emergency preparedness brochure to include a section about false information, warning of potential foreign disinformation campaigns and including a list of things citizens can do to fact-check information online. In the same year, the Swedish government announced the launch of a new agency, the Psychological Defence Agency. The aim is for the Agency to start operating in 2022 and will focus on psychological defence and combatting misinformation in Sweden by identifying, analysing and countering influence campaigns.

Improving the police response

The police play a key role in facilitating victims’ access to justice by investigating incidents of online abuse, harassment and intimidation. There is some evidence that providing training to police officers positively changes attitudes towards victims.

However, institutions have been slow to react to the rapid social changes motivated by increasing levels of user-generated content online, including social media. Law enforcement officials combating online harassment should have the skills, capacity and sensitivity to apply the law comprehensively and to support victims. However, given the scale of the issue, many police forces feel under-resourced and unqualified to tackle online abuse. Recognising this, some police forces have established dedicated police units to deal with online harassment, have increased budgets to deal with this issue and have established mandatory training for officials.

On the other hand, there are other practical barriers for the police to provide an effective response. Police need to identify perpetrators but to do this, they need to ask social media platforms to de-anonymise accounts, which can take a significant amount of time. Additionally, there are cases where victims of abuse can identify the perpetrator but the case does not meet the threshold applied by the police to start an investigation. Finally, it is unclear how police and the legal system can deal with online harassment that is cumulative and often lacks a single identifiable perpetrator.

There have been some efforts to criminalise sharing mis and disinformation. For example, the Italian government has created an online portal where people can report hoaxes. The reports are then passed to the police unit in charge of investigating cyber-crime, who will fact-check them and if necessary, pursue legal action. However, pundits and academics alike have reacted negatively to actions that give fact-checking faculties to the police.

Examples of good practice

In England, the Metropolitan Police established in 2017 the first police unit dedicated to tackling online hate crime funded by the Mayor’s Office for Policing and Crime. While only a low number of cases have been prosecuted due to the high CPS (Crown Prosecution Service) charging threshold for online hate, and the difficulties investigators face in obtaining information from social media companies, there is no doubt that police officers can use this as an opportunity to gain expertise. There is no information on how many police forces in the UK currently have a unit dedicated to cyber-crime.

In New Zealand, the Harmful Digital Communications Act 2015 set up a special complaint and mediation agency, NetSafe, to deal with cases of harassment through texts, emails, websites, apps or social media posts. The aim is to provide a relatively quick and easy way for harm to be reduced, including by getting harmful posts or messages taken down or disabled, while at the same time giving people appropriate room for freedom of expression. The website also includes sections on how to avoid scams and detect mis and disinformation online. Between April and June 2020, Netsafe received 6,880 reports overall, a 51 per cent increase compared to the previous quarter.

Governance and regulation

Governments around the world have attempted to adopt legislation to account for the changing role of digital technologies in politics. Legislative approaches focus on typifying online abuse and complement legislation on, for example, character assassination or threatening communication. Particular attention has been paid to regulating smear campaigns and the spread of misinformation as they can be used by foreign agents as tools to interfere with elections. Some legislative changes also require co-regulation between social media platforms and the government and to establish mechanisms to make social media companies more accountable and increase transparency.

Good practices in governance and regulation

In Wales, the Public Service Ombudsman agreed to the principle of referring some complaints against councillors back to councils for local resolution, and have developed a Model Local Resolution Protocol for Community and Town Councils. They do not explicitly mention online harassment or the spread of mis and disinformation but establish avenues to deal locally with members alleged to have not shown respect and consideration for others – either verbally or in writing.

In recognition of the increasing use of social media and networking websites in councillors’ communication activity, some councils have designed social media and communication policies to complement the code of conduct. Such policies aim to provide councillors and staff with guidelines on responsibilities when using social media. Some examples of clear and comprehensive policies include Gloucestershire County Council, Chard Town Council and London Borough of Tower Hamlets.

In the UK, online harassment can be a criminal offence under the Protection from Harassment Act 1997 (in England and Wales and with a separate section in Scotland) and The Protection from Harassment (Northern Ireland) Order 1997. Content that is offensive, indecent, obscene or threatening may be a criminal offence under the Malicious Communications Act 1988 or the Communications Act 2003 (England and Wales) and s38 of the Criminal Justice and Licensing Act 2010 (Scotland). The Draft Online Safety Bill proposes a duty of care for tech companies to assign them more responsibility for the safety of their users and to tackle the harm caused by content or activity on their services. This modifies the role of tech companies, from passive observes of discussions to active facilitators and moderators. It Is expected that the forthcoming Electoral Integrity Bill will cover the intimidation of candidates and undue influence, and digital imprints of electoral materials, though this will not cover all countries in the UK.

These changes would bring legislation across the UK closer to that of other countries such as Germany, where the Network Enforcement Act forces social media companies to remove hate speech and criminal content or risk a fine of €50 million. However, this legislation has been controversial as it is unclear where the line falls between preventing the spread of hate speech and limiting freedom of expression.

The European Commission recently upgraded the rules governing digital services in the EU through two legislative initiatives: The Digital Services Act (DSA) and the Digital Markets Act (DMA). Their goals are to create a safer digital space in which the fundamental rights of all users of digital services are protected and to establish a level playing field to foster innovation, growth, and competitiveness, both in the European Single Market and globally.

While not legally binding, it is worth mentioning here because of its potential for large scale reach the Code of Practice on Disinformation, part of the EU digital strategy to combat disinformation. It establishes voluntary self-regulatory standards to increase transparency in political advertising, facilitate the closure of fake accounts and demonetise sources of disinformation. In the US, President Biden announced the creation of a Task Force on Online Harassment and Abuse intending to develop strategies for social media platforms, federal and state government to flag and prevent online sexual harassment, threats and revenge porn.

Clearer legislation is a welcome step forward to deal with online harassment. Especially as it is undeniable that legislation changes behaviour, not only at an individual level but also among companies. Pioneering on how to deal with lack of transparency, Canada passed the Elections Modernisation Act (Bill C-76) to avoid foreign interference with elections and motivated Facebook Canada to launch their tool Facebook's Ads Library (FAL) to give the public more information about the political ads they see online. This regulation is accompanied by investment in digital literacy programmes to combat disinformation.

Limitations

Current initiatives to deal with online harassment in the public sphere are very welcome. However, they will likely be of limited impact because of the volume of online harassment we are observing and the time-sensitive nature of a problem that is continuously evolving.

Moreover, much of this focuses on dealing with abuse or false information once the harm is done instead of preventing it. Councillors and members of the public have the right to participate freely in the democratic process without fear of harm. Therefore, alongside these reactive approaches, a proactive approach that rejuvenates civic education and emphasises the development of digital and analytical skills should also be considered.

Additional work and advice to improve civility in public life

Alongside this report, we have published a practical guide for councillors which outlines the proactive approach to improve civility in public life taken by the LGA, WLGA, COSLA and NILGA on handling harassment and intimidation online which involves improving digital citizenship. The resources within that document include model rules of engagement, and guidelines to avoid the spread of mis and disinformation. They resulted from an extensive consultation among councillors and supporting officials, and a review of the most recent literature and best practice.

The recent publication of the Intimidation in Public Life: a joint statement on conduct of political party members by the Committee on Standards in Public Life (CSPL) was the result of extensive work by the Jo Cox Foundation and the CSPL to encourage parties to work together and agree on minimum standards of behaviour during election campaigns.

References

- Rossini P. Beyond Incivility: Understanding Patterns of Uncivil and Intolerant Discourse in Online Political Talk. Communic Res 2020. doi:10.1177/0093650220921314.

- Tambini D. The differentiated duty of care: a response to the Online Harms White Paper. J Media Law 2019;11:28–40. doi:10.1080/17577632.2019.1666488.

- Collignon S, Rüdig W. Lessons on the Harassment and Intimidation of Parliamentary Candidates in the United Kingdom. Polit Q 2020

- LGA. Councillors’ guide to handling intimidation. 2019

- EIGE. Cyber Violence (Crimes) Against Women and Girls. 2017. doi:10.17501/wcws.2016.1101

- Smokowski PR, Evans CBR. Bullying and Victimization Across the Lifespan. Bullying Victim Across Lifesp 2019:107–22. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-20293-4

- Lumsden K, Harmer E. Online Othering: Exploring Violence and Discriminaiton in the Web. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan; 2019. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-12633-9

- James D, Sukhwal S, Farnham FR, Evans J, Barrie C, Taylor A, et al. Harassment and stalking of Members of the United Kingdom Parliament: associations and consequences. J Forensic Psychiatry Psychol 2016;27:309–30. doi:10.1080/14789949.2015.1124909.

- Krook ML. Violence Against Women in Politics. J Democr 2017;28:74–88. doi:10.1353/jod.2017.0007.

- Collignon S, Rüdig W. Lessons on the Harassment and Intimidation of Parliamentary Candidates in the United Kingdom. Polit Q 2020

- Collignon S, Rüdig W. Increasing the Cost of Female Representation? Violence towards Women in Politics in the UK. Forthcoming 2021

- Prabhakaran V, Waseem Z, Akiwowo S, Vidgen B. Online Abuse and Human Rights: WOAH Satellite Session at RightsCon 2020. Proc. ofthe Fourth Work. Online Abuse. Harms, Association for Computational Linguistics; 2020, p. 1–6. doi:10.18653/v1/2020.alw-1.1

- Prabhakaran V, Waseem Z, Akiwowo S, Vidgen B. Online Abuse and Human Rights: WOAH Satellite Session at RightsCon 2020. Proc. ofthe Fourth Work. Online Abus. Harms, Association for Computational Linguistics; 2020, p. 1–6. doi:10.18653/v1/2020.alw-1.1

- Rezvan M, Shekarpour S, Alshargi F, Thirunarayan K, Shalin VL, Sheth A. Analyzing and learning the language for different types of harassment. PLoS One 2020;15. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0227330

- Pater JA, Kim MK, Mynatt ED, Fiesler C. Characterizations of online harassment: Comparing policies across social media platforms. Proc Int ACM Siggr Conf Support Gr Work 2016;13-16-Nove:369–74

- Pershan C. Moderating our (dis)content: Renewing the regulatory approach. Association for Computational Linguistics; 2020

- Pater JA, Kim MK, Mynatt ED, Fiesler C. Characterizations of online harassment: Comparing policies across social media platforms. Proc Int ACM Siggr Conf Support Gr Work 2016;13-16-November:369–74

- Prabhakaran V, Waseem Z, Akiwowo S, Vidgen B. Online Abuse and Human Rights: WOAH Satellite Session at RightsCon 2020. Proc. Of the Fourth Work. Online Abuse. Harms, Association for Computational Linguistics; 2020, p. 1–6. doi:10.18653/v1/2020.alw-1.1

- Rossini P. Beyond Incivility: Understanding Patterns of Uncivil and Intolerant Discourse in Online Political Talk. Communic Res 2020. doi:10.1177/0093650220921314

- Mckee Z, Mueller-Johnson K, Strang H. Impact of a Training Programme on Police Attitudes Towards Victims of Rape: a Randomised Controlled Trial. Cambridge J Evidence-Based Polic 2020;4:39–55. doi:10.1007/s41887-020-00044-1.

- Millman C, Winder B, Griffiths M. D. UK-based police officers’ perceptions of, and role in investigating, cyber-harassment as a crime. International Journal of Technoethics, 8, 87- 102. Int J Technoethics 2017;8:87–102.

- DCMSC. Disinformation and ‘fake news.’ Digital Culture Media Sport Committee, House Commons 2019;Final Report:1–109