Introduction

Despite progressive improvement in qualification levels over the last two decades, the UK still has a major challenge of low skills, which constrains the productivity of the national economy and is a barrier to individual earnings and progression in work:

- Some 6.7 million working age adults in the UK have low (level 1) or no qualifications. This represents 16.2 per cent of adults aged 16- to 64-years-old, rising to over one in five (21.9 per cent) of working age people between 50 and 64 years.

- Additionally, the UK has a digital skills deficit with an estimated 10 million adults lacking essential computer skills.

Improvement in adult skill levels has been hampered by a sustained decline in funding and participation in adult learning over the last decade. Despite additional investment in apprenticeship programmes, the net effect is a fall in adult funding of 35 per cent, or £1.9 billion in real terms, between 2009/10 and 2019/20. This is particularly significant for the Adult Education Budget, which funds basic skills and community level engagement in learning that declined by 52 per cent between 2011/12 and 2019/20.

In the context of COVID-19 recovery and national commitments to the levelling-up of regional economic performance, skills issues are rightly at the fore of public policy. Recent publication of the Skills for Jobs White Paper, Levelling Up White Paper and the Skills and Post 16 Education Act focus on transformation of the skills system as vital to realising the Government’s ambitions for a high skill, high wage internationalised economy.

Transforming adult skills in England relies on transforming the relationships between government, councils and combined authorities to hardwire ‘place’ and local democratic accountability into skills design, funding and delivery. This report calls for actions across three themes:

- Re-engineer the skills system – a consistent devolution of funding, delivery and control of adult learning across England. One that uses Local Skills Improvement Plans (LSIP) to bring employers’ intelligence and advice into existing skills planning partnerships, devolves commissioning to the local level to drive innovation and creates a national dialogue and evidence base on meeting skills supply tailored to meet local needs and conditions.

- Mobilise adult skills – reversing a decade of declining funding and participation by prioritising engagement and provision of people vulnerable to being left behind by changing labour markets and automation that will reduce reliance on low qualifications. Focusing on level 1 and 2 through a new community skills function for non-devolved authorities and a level 2 guarantee to create effective progression pathways to level 3 technical qualifications.

- Transform in-work learning – with 80 per cent of the 2030 workforce in employment now, closing the skills gap at work is essential. A step change can be achieved through more effective alignment of training and SME business support to drive the productive use of skills, alongside flexible funding to fuel innovation in learning design. Local employment opportunities can be captured with full devolution of apprenticeships levy funding to support skills and jobs brokerage that better prepares unemployed and low skilled people for work.

Labour market context

Long-term labour and skills trends in the UK show a continuing shift towards service-industry jobs and high skilled occupations, which are altering the nature of work tasks, employers expectations and adult skills demand. Structural changes are dissolving some of the hard boundaries between traditional job roles, with interpersonal skills, problem solving and creativity increasingly sought after by employers. Change is driven by technology and global markets, with digitalisation and the impact of climate change significant factors shifting skills demand.

Digitalisation – competence in computing and web-based tools is firmly established as a core skill, equivalent in importance to literacy and numeracy. The growth of e-commerce, requiring skills in web-design and low-code software, and automation of work tasks across all sectors increases demand for digital skills. Data shows that roles in digital technology are growing at three times the rate of all jobs in the wider economy. This demand makes people without digital skills less able to compete for work and people that lack qualifications more likely to be made redundant by automation.

Transition to net zero – the global climate emergency is stimulating cultural and behavioural change in society and is reshaping the economy. The growth of global markets for green goods and services and the requirements on employers to reduce the impact of their activity has major implications for jobs and in-work skills. The LGA Local Green Jobs report signalled an additional 500,000 jobs in the low carbon and renewable energy economy by 2030. But the impact of net zero will affect around one fifth of existing jobs, with either an increased demand for green skills or a requirement for in-work retraining.

While these drivers present a challenge, they are manageable where employers and workers collaborate to update skills and evolve work roles to keep pace with technological and regulatory change. For both digital and green drivers of skills demand, there are some entirely new work roles emerging, but a majority of skill need is adaptive: extending existing technical, administrative and craft skills to comply with new requirements and integrate the use of new technology into existing processes.

COVID-19 accelerated longer-term labour market trends and had severe consequences for many individuals and families across the country. The pandemic hit particularly hard in deprived and ethnic minority communities made vulnerable by poverty, poor quality housing and a reliance on lower skilled and insecure occupations. Qualification levels were vital for staying in work during the pandemic, with evidence that:

- adults with low qualifications were more likely to be furloughed than workers with degree level qualifications

- people in lower skilled occupational groups were less able to transfer to home-base working than people in managerial and professional roles and

- young people in lower skilled jobs experienced disproportionate levels of redundancies during the peak of the pandemic.

While jobs recovery after lockdown has been rapid, insecurity and the trend of falling employer engagement in training create a significant challenge for people with few qualifications at the margins of good employment.

Improving adult skills is a ‘place’ issue. With a national focus on levelling-up, addressing the underlying factors that cause low achievement of qualifications is vital to addressing embedded inequalities found particularly in urban, coastal and rural communities.

People with low qualifications tend, due to differences in income and access to transport, to be more reliant on local work than those with higher qualifications and in well paid occupations. Areas with low employment rates and low numbers of vacancies also have higher concentrations of people with low or no qualifications. Investing in and targeting skills training provides a means to both disrupt long-term patterns of exclusion and improve local prospects to attract jobs growth. Flexible and locally tailored skills training is vital to raise qualification levels and improve business performance in local economies.

Key issues for place-based adult skills

Improving the Effectiveness of the Skills System

The UK skills system is a complex web of funding streams, qualification frameworks and delivery arrangements, operating at differing scales and through national and devolved decision-making structures. Reform of adult skills provision and funding is vital to:

- reverse declining levels of investment over the last decade

- address the ongoing challenge of raising low level skills and promoting lifelong learning

- better coordinating a patchwork of progression pathways through technical and vocational education for people in work.

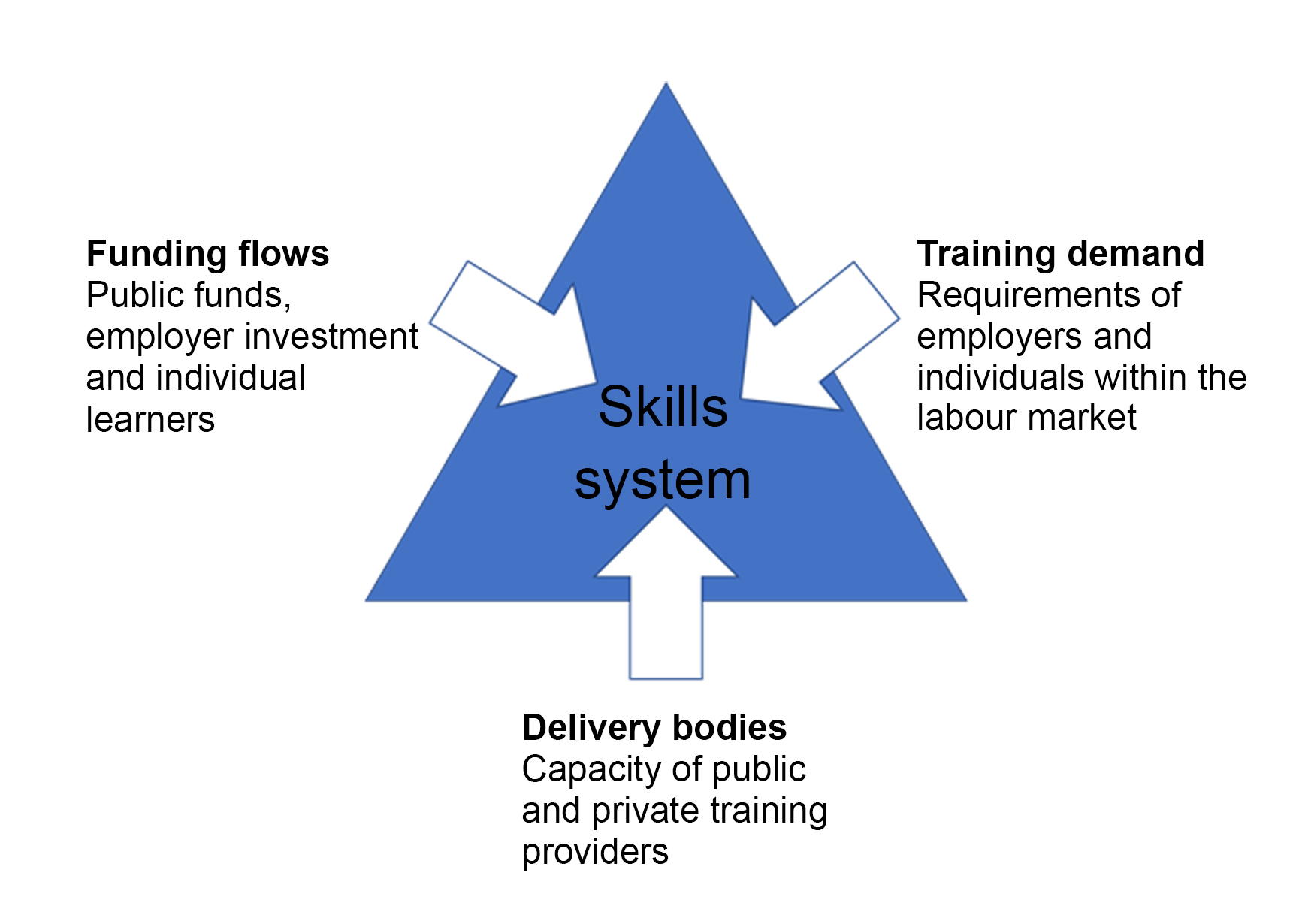

Devolution of skills planning should aim to improve all aspects of the system including funding flows, training demand and delivery to be more agile and responsive to changing employer demands – see figure 1.

Current policy has a particular focus on supporting employers to better articulate their demand for skills, through the eight Local Skills Improvement Plan (LSIP) trailblazers. LSIPs can make an important contribution to realising the full benefits of economic growth for local communities. But, to be effective, improved intelligence on skills demand must be embedded within a wider supportive partnership of public and private sector stakeholders with responsibility for planning and delivery of entry level and in-work training.

With their deep understanding of ‘place’, councils and combined authorities can convene partners to articulate local challenges for adult skills and identify key opportunities for growth. Local partnerships are uniquely positioned to:

- join up funding streams and skills provision with other employment and social programming to ensure pathways for low skilled residents;

- provide a nuanced view of needs and opportunity that is not visible from a national level, such as in the West Midlands Combined Authority’s apprenticeship levy transfer fund; and

- offer the leadership for locally focused sector skills growth and recovery plans, as in Peak District and Derbyshire and Shropshire Council.

An improved skills system requires a long-term settlement of devolved powers and stable funding to build confidence and realise the full potential of partnership working. The impact of an improved skills system depends on both individuals and employers recognising the personal and economic benefits of training and creating a clear demand for tailored provision.

Tackling Adult Low Skills and Unemployment

Despite a steady reduction in the number of adults with no or low qualifications, the UK continues to face a major challenge to improve adult skills. Around nine million working age adults in England have limited functional literacy or numeracy, of which five million have limited skills in both.

Tackling this challenge has been compromised by a sustained decline in funding and participation in adult learning over the last decade.

Despite recent increased investment in apprenticeships and level 3 provision for adults, there has been an overall fall in adult funding of 35 per cent, or £1.9 billion in real terms, between 2009/10 and 2019/20.

Most significantly the Adult Education Budget (AEB), important for commissioning basic skills and community engagement, has halved between 2011/12 and 2019/20, with a fall of 52 per cent in real terms.

Adult participation in English, Maths, and ESOL learning has declined by 63 per cent, 62 per cent and 17 per cent respectively, from 2012 to 2020.

Since 2019, responsibility for the use of AEB has been split in England between the national Education Skills and Funding Agency (ESFA) and devolved to the MCAs and the Greater London Authority. While devolution to combined authorities has demonstrated the effectiveness of local control of flexible budgets, partial devolution creates inequities in funding and effectively a two-tier system for skills planning across the country.

Despite evidence that engagement in learning can bring significant financial and career benefits for individuals, people with low qualification levels are the least likely to engage in training. Boosting participation in adult learning is vital to breaking long-term patterns of labour market vulnerability and exclusion. To achieve a levelling-up of adult skills, it is vitally important to increase the number of adults with essential skills, level 2 and higher qualifications. This requires an expansion of entitlements, a strategy to increase demand, and deliver provision flexibly (and with wrap around funding) to enable adults to fit learning around their lives.

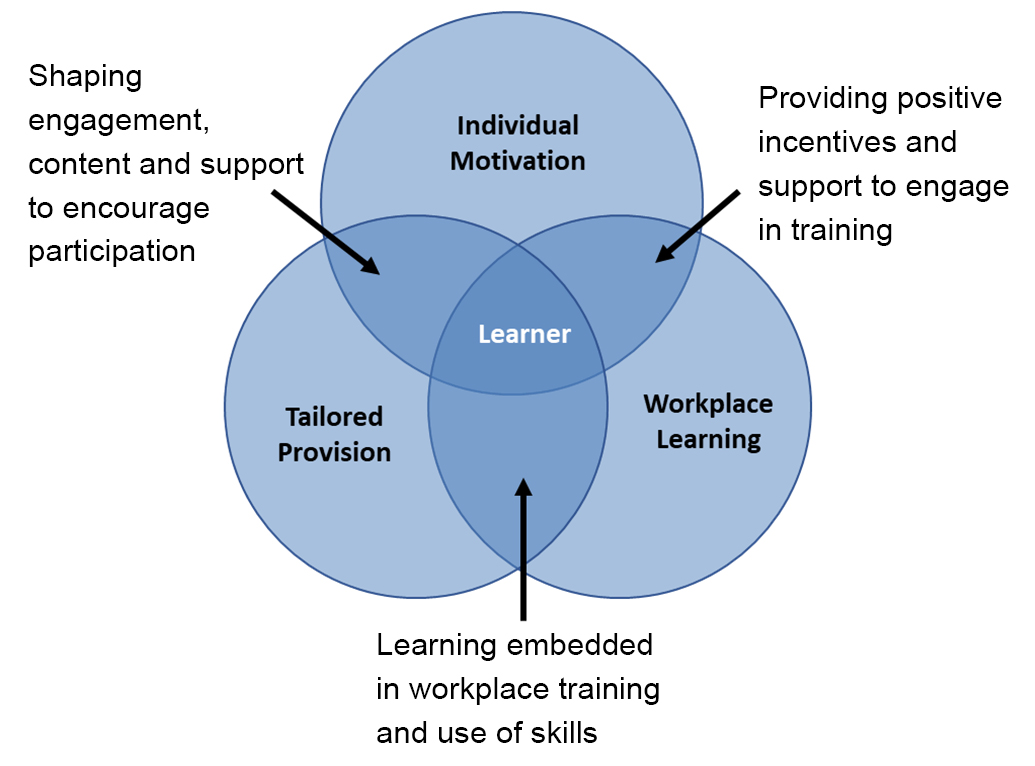

Local flexibility is key to improving the engagement, recruitment and training of learners. Overcoming the concerns of discouraged and low confidence learners and the practical challenges of cost, childcare and transport are vital for first steps into learning – see figure 2. Greater Manchester Combined Authority and Somerset West and Taunton Council have reshaped commissioning and local delivery to improve the impact of community learning.

Evidence shows that adult basic skills enable learners to progress onto further courses. Half of English learners (50 per cent) and 48 per cent of maths learners, attended a subsequent course during the year after completing their Skills for Life funded course, with many of these learners progressing onto higher level courses.

Short courses of unitised provision or narrowly focused training on a specific skillset responding to labour market shortage areas, can be highly effective in both providing a pathway into demand sectors of employment and addressing specific skills gaps identified by employers. As shown in case studies from the West Midlands and Liverpool City Regions, Combined Authorities have been able to use devolved AEB to encourage experimentation in course content and delivery to address identified skills gaps. Funding has also been used to connect with community provision, such as in Essex to offer leisure interest training in electric vehicles. This programme not only encourages the use of green vehicles, but also provides a potential first step into learning for adults.

Skills advancement in work

With 80 per cent of the 2030 workforce in employment now, closing the skills gap at work is essential to creating a high skilled economy, but also key to address growing levels of inequality in the labour market. Improved skills not only improve individual jobs mobility that can lead to higher lifetime earnings, but can help firms to raise their productivity and retain skilled workers; an issue that has become particularly important in a post-Brexit context.

Compared to other OECD countries, the UK has a significant gap in workforce participation in training among low skilled workers. With only half of workers indicating that their skills levels are well matched to their job roles, there is significant scope for employers to utilise existing capabilities, with focused training to better calibrate skills to work tasks.

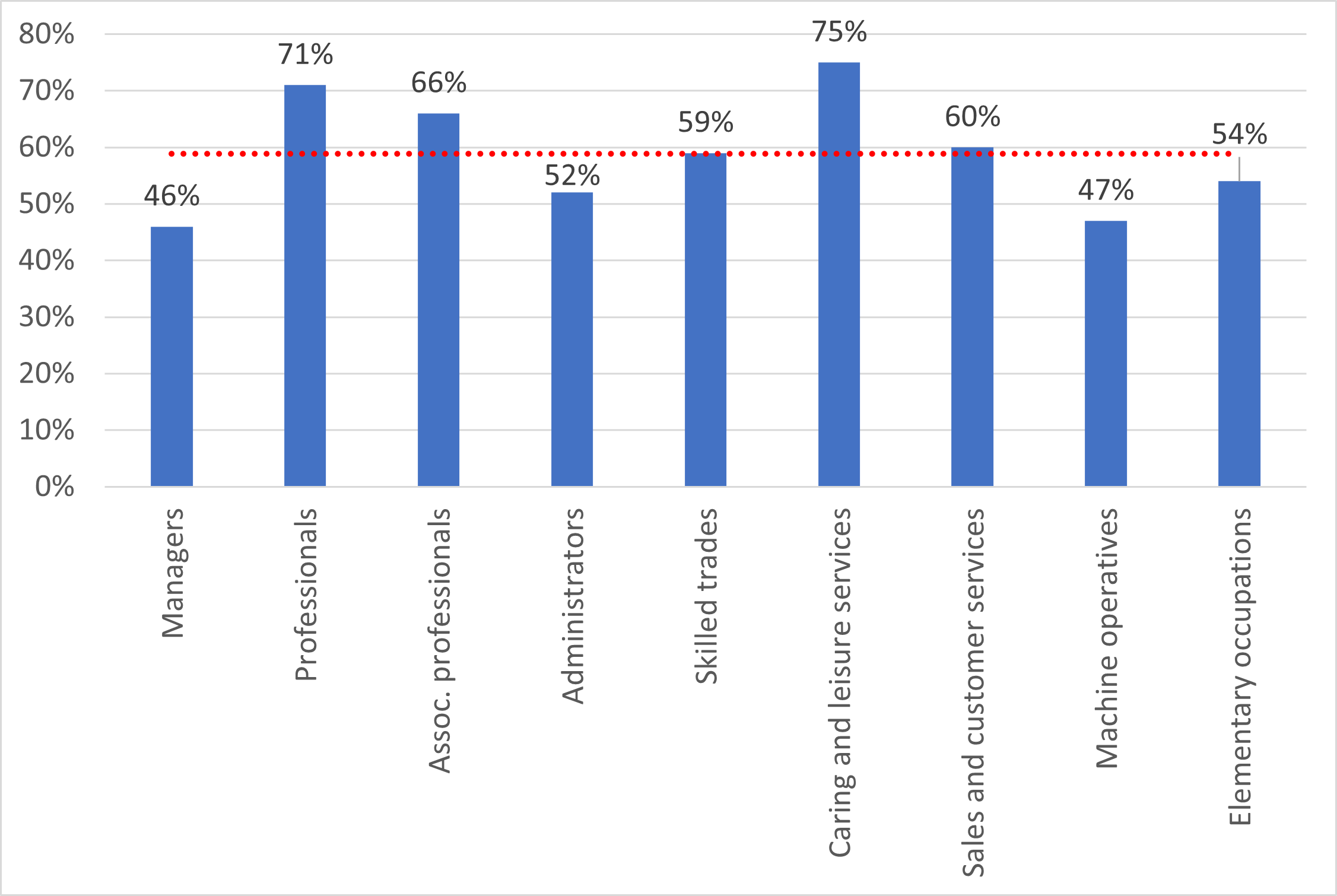

Across all occupations only 60 per cent of workers receive training, with greater investment in professional and associate professional jobs compared to operative and elementary roles. There are also qualitative differences in the types of skills training provided by occupation, with more developmental training in management, supervision and technology (skills transferable between jobs) available to higher skilled occupational groups, whereas lower skilled groups are more likely to access mandated training in health and safety, induction and workplace technology – figure 3.

Adults with little recent experience of learning or that are working in occupations offering just mandatory training are at a high risk of being left behind in skills development. Across the adult population, the take up of learning since leaving full time education is more than double for middle class than for working class social groups. Of particular concern are older workers, in declining sectors of employment, who have low levels of educational attainment.

A barrier to increasing in-work training is the declining quality of work:

- over the last decade, in the UK there have been rising levels of precarious employment, with a current estimated 3.6 million workers in insecure work and one in five jobs paid less than the real living wage.

- in the period following the financial crisis, between 2008 and 2018, two thirds of growth in employment was in ‘atypical’ roles including self-employment, part-time, temporary, zero-hours and agency contracts.

- the changing profile of employment is reflected in the subjective perceptions of the quality of work, which shows a decline over the last 30 years, with a marked reduction in job satisfaction levels among the lowest earners.

A greater use of short-term and casual contracts means that employers may not be incentivised to invest in the skills or the training of their staff. Additionally, workers with low or unstable pay will be unable to meet the costs of training themselves, particularly in a context of the current cost of living crisis, adding to participation gaps.

Locally defined provision can support the development of in-work skills by more effectively aligning business support and training offers. For example, Kirklees Council is working with employers to map skill requirements from entry through to higher level, providing advice on available sources of funding and identifying gaps in training provision that can be met through local and regional programming. Bristol City Council is aligning its ACL, apprenticeships and employment support to ‘stitch-in’ skills progression at work.

Policy conclusions and recommendations

Across the three themes of this study, building stronger partnerships is the basis for accelerating improvements in adult skills levels. Local and national government need to collaborate at political and official level to hardwire ‘place’ and local democratic accountability into the design, commissioning and delivery of skills and employment interventions, as advocated in the LGA’s Work Local – Unlocking Talent to Level Up report. Empowering local government to do more would allow Whitehall to re-focus its resources where it can be most effective and reduce the need for a large national level bureaucracy.

Improving the effectiveness of the skills system

- There needs to be a more consistent national approach to devolution to avoid a two-division system. As the LGA suggests, full devolution can be achieved far sooner than the 2030 target, but to establish collaborative structures an interim arrangement of a duty to consult with non-devolved areas should be put in place ahead of new governance arrangements. The regional structures being created by DLUHC provide a mechanism for both accelerating devolution and any interim arrangements.

- LSIP pilots in England rightly provide a focus on employer voice and leadership on skills demand, but implementation must be integrated into existing Employment and Skills Boards and SAPs, where they these are working well. Strong partnerships arrangements should not be undermined by new initiatives, where existing partners are able to improve employer engagement.

- The DFE should undertake an urgent review of existing national skills commissioning arrangements to identify how ‘place’ can be more clearly embedded in decision-making. Bootcamps have shown that national commissioning limits the scope for engagement of more knowledgeable and better-connected local providers already engaged with key employers and communities.

- Government should improve sharing of data held across government with local authorities and skills partnerships in England to inform labour force planning. The Government’s local employment and skills dashboard are a good start. With reduced flow of foreign workers after EU exit able to fill gaps in skills and labour supply, local areas need to develop more strategic approaches to align supply and demand for labour. This is a national / local issue that requires stronger collaboration.

- National and local government in England together with the LGA should ensure that a clearer focus on adult skills needs is accompanied by a more nuanced approach to skills and employment monitoring. Moving away from a blunt output model of performance would allow for more instructive measures of economic and social value of learning and progress towards lifetime learning goals.

Adult skills

- National funding cuts to adult skill budgets over the last decade need to be progressively reversed, with increased investment and flexibility available to local areas commensurate with identified local need, as identified in local skills strategies.

- Non-devolved councils in England should be given a new ‘Community Skills’ function to plan, commission and have oversight of all adult skills provision up to Level 2 for their area including Multiply and AEB. This would enable them to coordinate what is being delivered and how it fits together.

- DFE funding for adult skills needs to have more security beyond annualised contracts to enable further education providers including colleges, employers and local government to more effectively plan and develop provision. Government should work towards a settlement for skills (3-years) that provides a basis for local innovation.

- The national Level 3 guarantee needs to be matched with an expansion of entitlements, a strategy to increase demand, and deliver provision flexibly (and with wrap around funding) to enable adults to fit learning around their lives.

- Training and IAG for unemployed people should be disconnected from benefits and form part of locally defined provision linked to lifetime skills development. To improve pathways to skilled employment, work focused training should include wrap around support.

In-work progression

- Working together, national and local government in England need to achieve clearer alignment between skills provision and business support, reshaping the function of Growth Hubs to focus on skills and productivity. Government should ensure that councils and combined authorities have the funding to provide practical support to SMEs in their areas to improve workforce planning and skills utilisation and to understand the financial and performance benefits of investment in skills.

- DFE should build on the experience of bootcamps and flexible AEB to increase the volume of locally defined employer-based short course provision in England. Increased funding and incentives to pilot in-work training, in priority skill areas, can accelerate the development of new qualifications reflective of employer demand.

- Government should accelerate the devolution of apprenticeships levy for use by SMEs. Greater local flexibility in England should include powers to deploy unused funds to support local authority led skills brokerage arrangements and delivery of pre-apprenticeship training to prepare low skilled workers to undertake formal qualifications.

- Government should award additional funds to expand the availability of personalised in-work coaching and IAG support for low skilled adults and people in insecure employment. Local areas can use labour market intelligence to target employer and workforce engagement in support services.

- Local skills partnerships should improve the information flow to employers and workers about local learning opportunities. Information on training courses should be made available to residents and adults in the workforce through employer groups, local community learning centres and trade unions to increase entry into IAG and training.

Case studies

Learner and employer perspectives

Learner perspectives

As outlined in the Kirklees case study, the Council runs first steps provision, making training accessible to residents who are either looking to enhance existing skills or change career path. They have been working with local providers to deliver training in centres across the area with a specific focus upon its most deprived neighbourhoods.

First steps provision

ACL local first steps courses allow local adults to return to learning to gain skills that will enable them to access employment or change career. Learners in Kirklees were undertaking a food hygiene course, which for some was a way to “build confidence in the kitchen [that could form the basis for] a food business in the future” and others as a start “do something different” from their existing job. Local delivery of learning was an important factor for individuals with caring responsibilities, with one participant commenting: “so, it’s just around the corner. It means I can still get back and pick up my kids on time.” Some of the learners in Kirklees had taken courses in the past, but had dropped out because of conflicts with childcare responsibilities.

These short courses are seen as lower risk and less daunting for adults that been outside of formal learning for some time, when compared to commitments lasting 1 and 2 years. Engaging in first steps learning was seen as a way to improve learners’ position in the labour market, with one participant noting: “if you haven’t got the qualifications that employers want, your application will be pushed further down the list of applicants”. ACL has opened up possibilities for additional learning and in particular gaining English and Maths qualifications. Participants were also enthusiastic about their improved job prospects, saying that they expected to be snapped up by employers.

Engaging learners in the community

Information on courses was obtained by learners through multiple sources including school newsletters, the Council’s website, social media channels and word of mouth. One of the learners commented that she saw the information and intended to send it to her cousin, but decided that she would take the food hygiene course with him. She said: “and then, of course, my cousin wasn’t able to attend. So, I’ve come anyway just so I’ve got the certificate and have the option to use the qualification in the future".

Local community venues were important for the learners, both because of hesitancy in accessing remote learning: “I cannot deal with online training” and also that use of familiar venues helped learners to overcome concerns about returning to learning. One participant commented: “I was a bit hesitant, you know, a bit anxious and a bit of anxiety in terms of going back out into the world and being around people, especially people that I don’t know.” This was important both as a factor in undertaking the learning, but as a precursor to returning to work.

Employer perspectives

As outlined in the Peak District and Derbyshire Hospitality case study, the task force are working together with local councils, schools, colleges and other key stakeholders to both address short-term recruitment challenges and reshape the perceptions of, and the routes into, the tourism and hospitality sector over the next decade.

Tightening labour market conditions

In a context of tight labour market conditions, employers experience considerable difficulty recruiting people to the sector, particularly businesses in rural areas with limited public transport. After COVID-19 there are fewer young people and adults available and looking for work in the sector and there are changing expectations about pay and working hours that need to be met. An employer said: “well, my biggest challenge, without a doubt, is recruitment. I mean, day in and day out. It’s preventing us from moving forward, almost, now […] I take four or five calls a day from people that want our services, and we can’t service them because we can’t get people in.”

The pandemic has impacted on not only the number of people available, but their willingness to work in customer service roles: “the one thing that I’ve noticed after Covid, is that I’ve had a lot of people apply, and then when I contact them, say, ‘I’ve lost my confidence. I’m sorry. I’m going to have to pull out.’” Some employers on the task force are paying above age wage rates and varying contracted hours by moving away from traditional shift patterns and offering a four-day week. While difficult to operate for some hospitality roles, this flexibility has helped employers to be more competitive in recruiting staff.

Impact on skills and training

Employers are also working through the task force to improve the responsiveness of training provision to reflect both the current specific skill needs and to vary the pathways to qualification. An employer commented: “the traditional route through colleges is not as attractive to people coming into the industry, because they actually want to be working on the job in a professional kitchen.” By combining on-the-job training with day release and bespoke technical short courses, employers aim to build tailored packages that meet their skill needs, while also creating attractive opportunities for staff.

Flexibility of provision remains a challenge, as one or two-year courses are no longer attractive and are not suited to adult career changers coming into the industry. The workplace apprenticeship model needs to be able to accommodate specific technical training modules, but also work for small employers, typical to the sector. An employer commented: “when you’re operating out of a very small kitchen, it’s sometimes difficult to take on the responsibility of a full-time apprenticeship. Whereas, if you knew that you’d got an apprentice for maybe, one, two days a week, that feels more manageable for some of those very smaller kitchens.” Collaborative approaches to recruitment and training offer significant advantages to smaller employers and to recruits that gain experience across a range of settings.

Resources

Full report

A full version of the report is available on the Heseltine Institute’s website.

(Please note that the full report is not in an accessible format)