Our impact at a glance

An excellent initiative to be part of, learning from case studies across the country, a strong design methodology underpinning the projects

Karime Hassan, Chief Executive, Exeter City Council

We've picked up so many ideas from everyone else – from hearing about their journey but also the solutions they've come up with. When people were presenting we were saying 'Oh yeah, that'd be great for Bolsover!

Kaye Twomlow, Chair of Bolsover Skills & Employment Partnership

About the programme

Using design skills to grow the economy

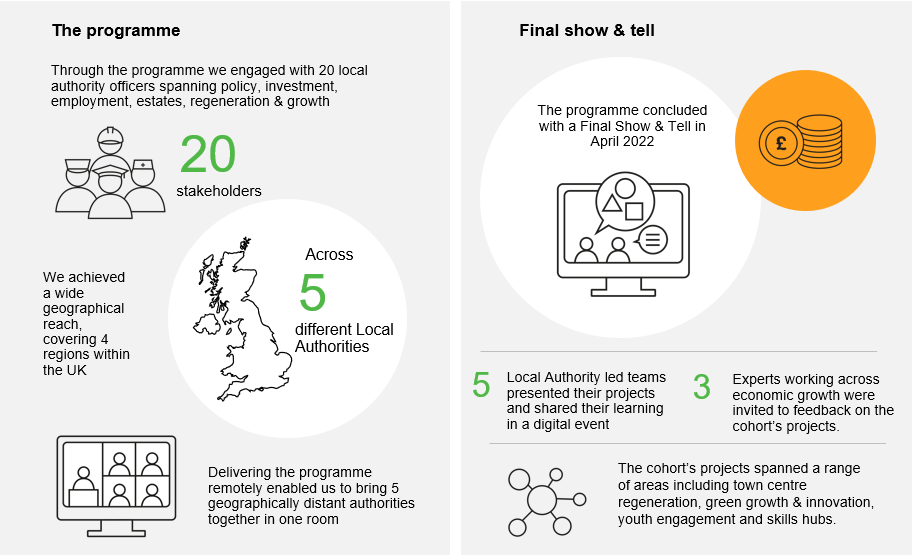

Overview

Since 2015, Design Council has worked in partnership with the Local Government Association (LGA) on growing the public sector’s design capacity, enabling it to deliver more efficient and effective public services and improve people’s lives.

Our joint work has helped more than 85 local authority teams reframe their challenges, prototype innovative solutions, and take decisive action to the benefit of local communities. Together, we have improved services across a diverse portfolio, including adult social care, housing, and climate change mitigation.

The Economic Growth Design Skills programme continues in this vein, supporting councils in addressing economic growth challenges in the aftermath of the Covid-19 pandemic and the context the progressive digitisation of the economy.

Drawing on Design Council’s ‘Framework for Innovation’, and with the support of our Design Council Experts, the programme enabled councils and their partners to further explore the aspirations of their communities, placing these at the heart of their plans for local economic growth.

Due to social distancing measures, the programme was delivered online via Zoom.

Programme experience

The programme brought together five local authority teams from across England: Bolsover, Darlington, Havant & East Hampshire, and Exeter. The multidisciplinary teams benefitted from a tailor-made capacity building programme which included workshops as well as case studies.

Participants were joined together in a community of practice, sharing insights across authority boundaries and providing helpful feedback along the way. Teams received support from Design Council Experts and the Design Council team, helping them apply design principles to live projects relating to training, jobs and economic growth.

Projects explored a range of opportunities and challenges. Teams investigated how to better engage younger demographics on jobs and skills; how to take a heritage-led approach to town centre regeneration; and how to develop innovation centres in response to the climate emergency.

Workshops were designed to help teams appreciate and consider the systemic nature of economic growth, and to provide them with the tools needed to build new partnerships and connect multiple concerns and interventions.

Design for Planet & Levelling Up

While focused on economic growth, the programme also explored ways to reframe participating councils’ challenges and opportunities to actively help address the escalating climate crisis. This is in line with Design Council’s stated ambition to galvanise the UK's design community to address the climate emergency as set out in our ‘Design for Planet’ mission.

The cohort led the way on this, whether proposing to set up forward-looking innovation centres for net zero research, or creatively using existing built environment assets in the regeneration of their town centre. Design Council looks forward to seeing how these projects develop over the coming years.

The programme has responded to the government’s call to level up the regions. It shows how councils can restructure local economies, seed green jobs in the community, and build virtuous circles of economic interdependence between sectors. It furthermore demonstrates the key role design plays in creatively reimagining the future to the benefit of residents, communities, and the planet.

Map of authorities and projects

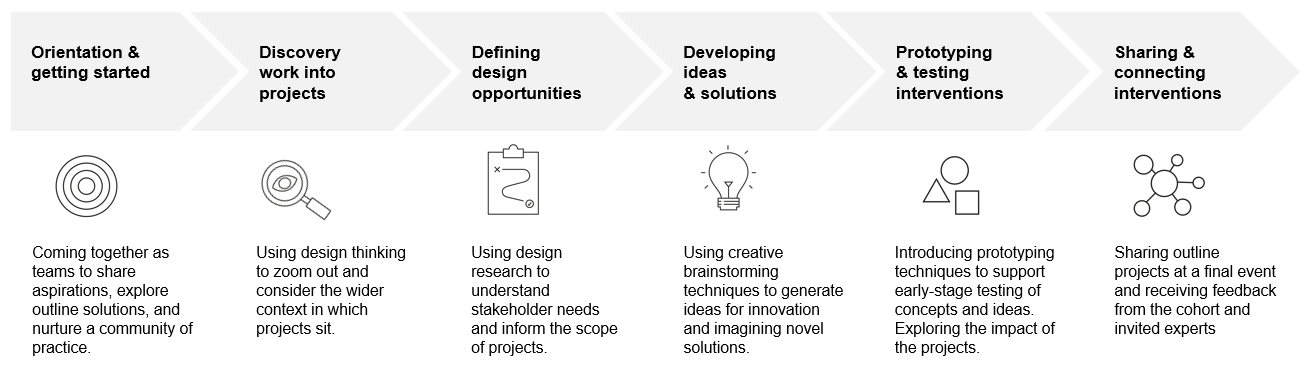

The journey through the programme

The evaluation approach

Capturing our learning and data

The LGA Economic Growth Programme reflected a new 'pared back' delivery model for both the LGA and Design Council, removing expert Coaching Calls between workshop sessions. To establish the impact of this, Design Council placed greater emphasis on evaluation of the programme, monitoring team progress via learning journals and zoom polls, as well as post-workshop debriefing meetings with experts.

The LGA Economic Growth Programme reflected a new 'pared back' delivery model for both the LGA & Design Council, removing expert Coaching Calls between workshop sessions. To establish the impact of this, Design Council placed greater emphasis on evaluation of the programme, monitoring team progress via learning journals and zoom polls, as well as post-workshop debriefing meetings with Experts.

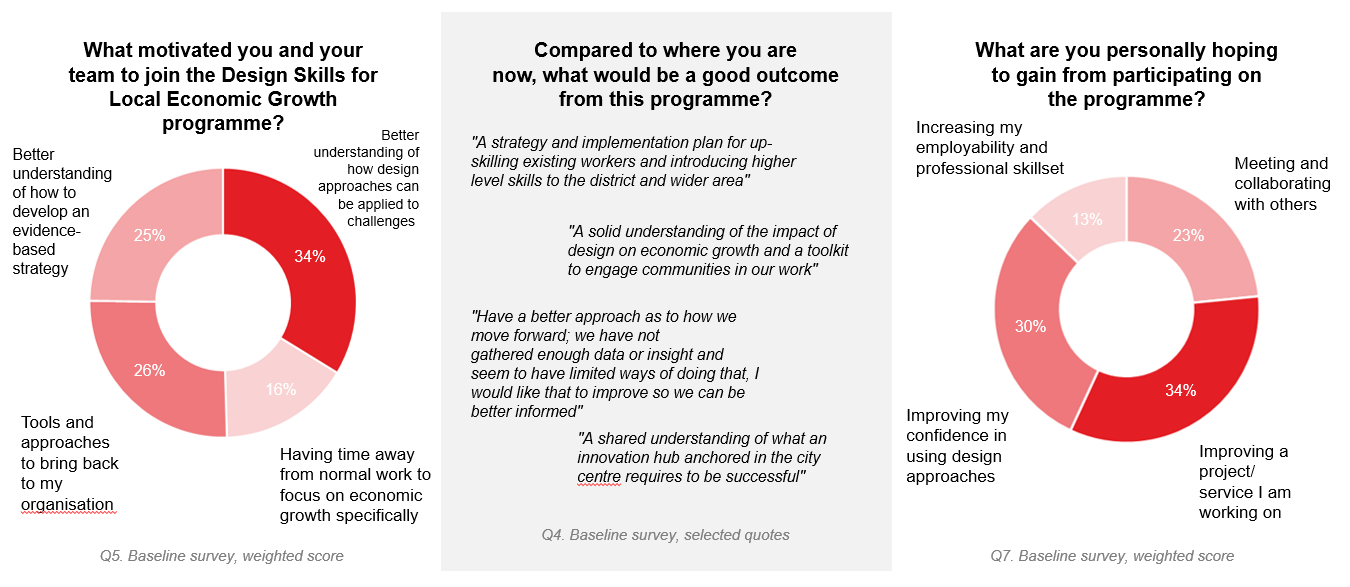

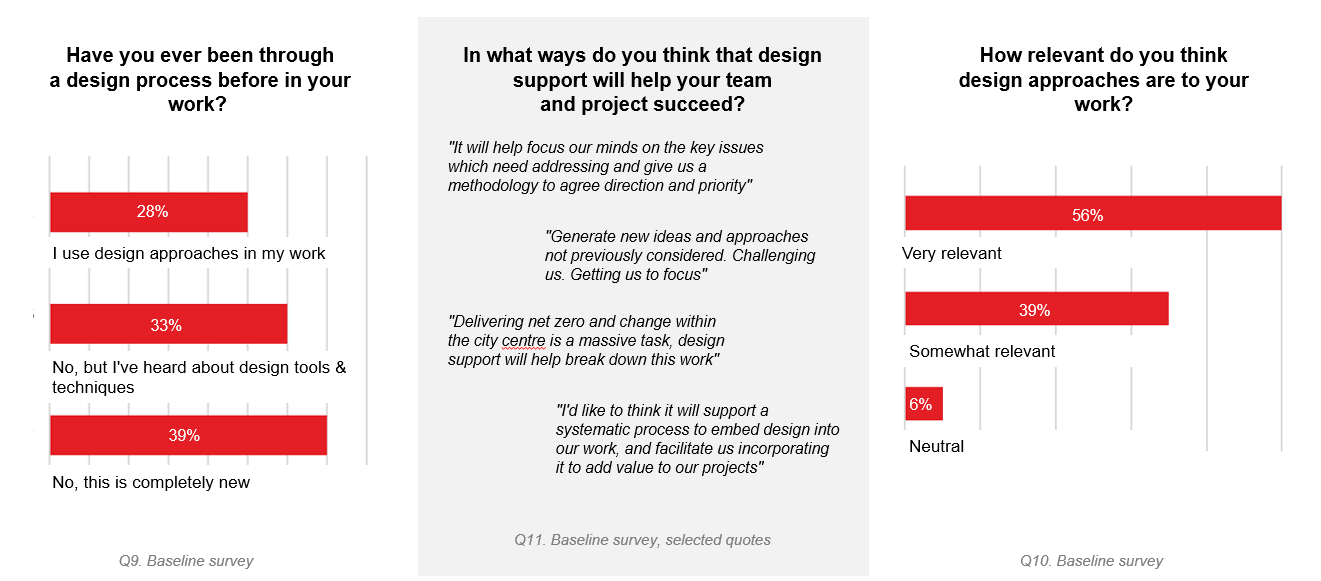

Participant reflective journals and surveys

Standardised baseline & endline surveys were issued at the start and end of participants' journeys to provide a comparative method of evaluating the overall impact achieved by the programme. These surveys encompassed motivations & aspirations for the programme, current policy context & existing design knowledge (baseline), as well as impact, benefits & overall experience (endline).

Additionally, two learning journals were distributed to participants – the first after Workshop 1, the second after Workshop 3. These journals acted as touchpoints between workshops, enabling participants to reflect on the tools & learnings gathered so far and feedback on their experience of the programme.

Zoom polls

Zoom polls were introduced at the end of each workshop to generate instantaneous feedback on the delivery of that session. Participants were asked to rate their satisfaction with the workshop on a scale from 1 'Very unsatisfied to 5 'Very satisfied'. In all four workshops, participants reported to be either 'Satisfied' or 'Very Satisfied' with delivery of the session.

Final Show & Tell

The programme culminated in a 'Final Show & Tell', enabling teams to present their projects to a panel of three external experts. As noted by the Design Experts, these presentations, particularly the articulation of the team's journey through the four design phases, acted as a key demonstrator of design-added value.

In addition to cohort presentations, part of this session was dedicated to participant feedback on tools & overall programme experience. Feedback to design tools, set out within the four Double Diamond phases was provided via Miro; feedback to the overall programme itself was provided verbally via wider discussion with the cohort – this was later transcribed to produce testimonials.

Baseline Survey – Policy context

The Baseline survey was used to establish existing economic growth policy amongst authorities.

According to feedback, the majority of authorities (47 per cent, n=19) were 'delivering programmes & projects against an up-to-date economic growth/ recovery strategy'.

Furthermore this same percentage revealed that their strategy made 'substantial reference to, and was informed by, more than 3 national policies'. These policy areas are illustrated within the word cloud right). Recurring themes include 'Levelling up', 'Covid Recovery' and 'Green Jobs'

Almost half of officers undertaking the survey had led previous work across economic growth, such as a green skills strategy, Neighbourhood Renewal Fund and Youth Hub project.

The value of design

Baseline Survey - motivations & aspirations

Baseline Survey - existing knowledge of design processes

What we learnt about the value of design

Local authorities tend to be faced with multiple challenges at once. This can make project development tricky as issues often overlap and are co-dependent. Design thinking can be a useful way to start grappling with such ‘wicked problems’, enabling teams to identify the core issues their communities are faced with and explore the underlying drivers. Gaining clarity in this way in turn allows teams to move forward with speed and purpose. As one programme participants observed:

“Strategic design techniques is a great way to break down the challenge, think about the different elements and make it more focussed. It also helps you think about who you might want to engage and why - what do different stakeholders get from the project?”

Bolsover District Council officer

Strategic design enables teams to be nimble and test ideas before going full scale. Proceeding in this way can help test assumptions and flush out any issues and blind spots before major investments are made. As one of the participants said:

Taking a design-led approach means you can do something at pace – be agile – without spending lots of money which you might regret later. We went from a fixed view about what an innovation building would look like to thinking more holistically about this.

Exeter City Council officer

Ultimately, the value of design derives from its capacity to interrogate and reframe critical questions, and propose low-cost designs or interventions that can be rapidly prototyped before scaling up to more permanent solutions.

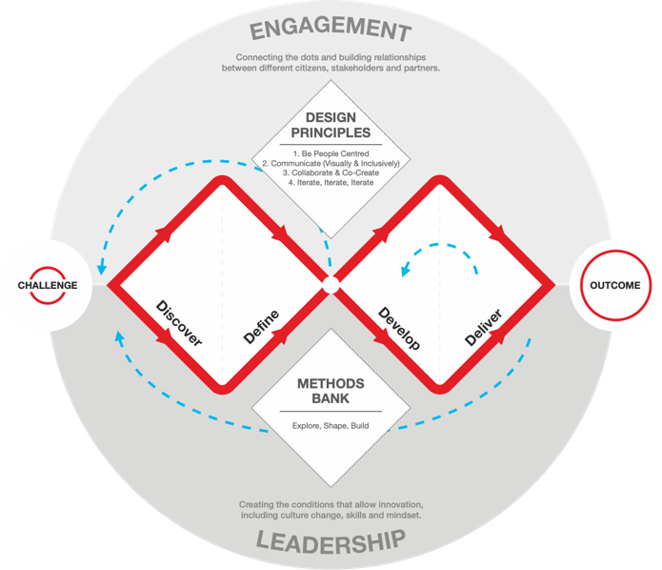

In developing their projects, teams used Design Council’s Framework for Innovation to map issues, explore solutions and test assumptions. The framework is a tried and tested approach for rapidly moving from an initial challenge to prototyping, testing and delivery. It includes specific tactics and methods that designers and non-designers can use when working with a challenge.

The framework is structured around the following principles: Start with an understanding of the people using a service, their needs, strengths and aspirations. Help them gain a shared understanding of the problem and ideas. Enable them to work together and get inspired by what others are doing. Iterate to spot errors early, avoid risk and build confidence in the ideas.

These principles are echoed in the Double Diamond, which involves four main phases:

- Discover which helps teams understand and interrogate the challenge they are addressing. This involves spending time with the people and communities that are affected by the issue in question, actively involving them as part of a co-creation process.

- Define which mobilises insight gathered from the discovery phase in order to help teams interrogate and redefine their challenge.

- Develop which helps teams explore different solutions to their redefined challenge. This includes seeking inspiration from elsewhere and co-designing with a range of stakeholders.

- Deliver which involves testing out different solutions at small-scale, rejecting those that don’t work and using freshly generated insights to improve the ones that do.

The design tools found in the framework of innovation – and supported by the underlying Double Diamond – are highly effective and have broad applicability; from issues of economic growth to sustainable development and climate change mitigation. As one local authority officer from Exeter City Council observed:

We will be using the Double Diamond to help deliver net zero with Exeter City Council. This will include working towards the development of a City Dashboard to address net zero challenges.

Exeter City Council officer

The following sections of this report set out the way participating authorities used the Framework for Innovation to explore their economic growth challenges and opportunities. For clarity, they have been structured around the four phases of the Double Diamond: discover, define, develop, deliver.

A framework for innovation

Discover: Scrutinising the challenge

Design is about understanding a given challenge or opportunity and then devising solutions to address these – ideally together with the stakeholders who are affected by the issue and stand to benefit from the outcomes. Too often designs are created based on assumptions that have not been appropriately interrogated. This almost inevitably leads to suboptimal solutions and risks wasting time and resources.

The Design Skill Programme’s design-led approach ensured that assumptions were shared among participants and interrogated up front. Teams understood the risks associated with poorly defined challenges, and addressed these by mobilising the design skills introduced through the programme. As one participating officer said:

Inception is the phase where the project is less defined and there is a temptation to jump forward to an answer. The design-led process helps to define and consider challenges and outcomes more fully.

Darlington Borough Council officer

Teams were invited to consider and interrogate the challenges and opportunities relevant to their communities, thinking in particular about the knowns and unknowns of their proposed projects as well as who (or what) might act as enablers and barriers to successful project delivery.

Insights from this activity were mobilised in the development of a so-called ‘Challenge statement’ which succinctly summarises the problem or opportunity being explored, who it is affecting, where it is being observed, and why resolving it matters.

Teams were then asked to use insights from the challenge statement and turn these into a so-called ‘How might we…?’ statement. In doing so, they pivoted from sketching out the challenge or opportunity to thinking about how to frame the issue in a way that lends itself to thoughtful resolution.

Once this had been workshopped – and participants had had the opportunity to explore and debate each other’s understanding of the challenge – teams then identified the stakeholders. Concretely, teams were invited to reflect on who the stakeholders were, how they could be engaged in resolving the challenge, and the role they could play in designing, delivering and maintaining the project.

The list of stakeholders was exhaustive, but included residents and community groups, statutory bodies (e.g. highways authorities, planning authorities, Dept. for Work and Pensions, the police), local decision makers (e.g. Councillors, MPs, town boards), third sector organisations (e.g. skills providers, charities such as Historic England and Arts Council), and private sector stakeholders (e.g. local businesses and BIDs, local developers).

This design-led approach enabled teams to move forward with purpose and speed, getting off the mark with work on otherwise complex projects. As one participant observed:

The tools enabled us to break down the project ideas to fully understand the objectives as well as what we wanted to achieve.

Bolsover District Council officer

Define: Reframing the challenge

Engaging with stakeholders – and facilitating them in design-led activities to draw out responses and insights – forms an important part of the design process. User-engagement can help generate more nuanced ideas and solutions, and can furthermore help flag up problematic assumptions and potential trip wires by allowing proposed interventions to be explored from different angles.

For the next phase of the programme, teams were therefore invited to collect findings from external and internal stakeholders, following a user-centred research methodology. Insights collated were clustered, themed and workshopped by teams with support from Design Council Experts. Participants were invited to reflect on which ideas had greater potential – and should therefore be prioritised – and which felt less urgent to the council and local communities.

Teams responded well to the introduction and mobilisation of user-generated insights, with one participant observing:

Insight and research helped us further develop the challenge and is a useful approach to use for other projects. It enabled a focused project, with clear steps to the end goal.

East Hampshire officer

Having mapped and interrogated the benefits of various possible interventions, teams were asked to produce a forward-looking vision statement. This enabled them to come together and agree the overarching objectives for their intervention. It furthermore provided direction to projects, with team members co-creating and buying into an overarching idea. As one programme participant observed:

The development of a vision statement allowed the project to move forward with purpose. It gave it grounding.

Exeter City Council officer

Having agreed on a statement summarising their vision, teams were asked to illustrate that vision in the form of a vision poster. In doing so, they mobilised insights from the stakeholder mapping activity, explored how stakeholders stand to benefit from the project and how they can be involved in its planning and delivery.

In design terms, the translation of a statement into a poster represents the design achieving a higher degree of fidelity. In simpler terms, it constitutes another opportunity and prompt for teams to reflect on what excites them about their vision, what the impact of the project will be, and what stakeholders might say.

This simple exercise was welcomed by project participants, including an officer from Bolsover who provided the following feedback:

It is a really good template by which to identify priorities and an agreed way forward. It helped us work through a hugely complicated and complex problem to define how we might take action to start addressing the issues.

Bolsover Council Officer

The workshop also included a case study. Delivered by Director for Regeneration and Business Development at Southend-on-Sea Borough Council, the presentation explored effective and empathetic ways to engage younger demographics (18-25s) on skills, knowhow and capacity building. Top tips from the case study included:

- guidance on how to take a data and engagement-led approach to engage different cohorts

- tips for how to map support for different pathways

- an overview of gaps and obstacles to interventions.

Insight and research helped us further develop the challenge, and is a useful approach to use for other projects

East Hampshire District Council officer

Develop: Exploring solutions

Where the two first phases of the double-diamond are about exploring and defining a given challenge, the third phase is about agreeing and testing solutions. This involves co-creating design interventions together with relevant stakeholders and taking inspiration from other projects

Teams explored possible interventions using a so-called ‘creative matrix’: a time-bound approach to brainstorming which increases the volume, focus and usefulness of ideas. Working in the matrix, teams tested ideas against different user groups or audiences. This helped them progress their thinking by challenging them to put themselves in the shoes of different stakeholders. One observed:

The matrix got me thinking about the benefit to the involvement of the different stakeholders - both for them and the project. In future projects, it will be helpful to categorise stakeholder involvement and also to identify further stakeholders where there are potential gaps in our assumptions.

Bolsover District Council officer

Having completed the creative matrix, teams were asked to test interventions against Design Council’s so-called ‘Benefits matrix’. This is a tool which helps stakeholders come together and discuss interventions, identifying whether these are strategic in nature, represent quick wins, or are non-essential. One participant observed that the matrix represented

[A] structured way to test ideas at speed. It can help us avoid expensive mistakes by simply opening up ideas to explore and challenge in a disciplined and inexpensive manner.

Exeter City Council officer

The workshop also included a case study, delivered by the Chief Executive of Historic Coventry Trust. Taking the recent regeneration of the Burges area of Coventry (a conservation area with locally listed buildings) as a case, the presentation explored how councils can take a design- and heritage-led approach to town centre regeneration.

Top tips from the presentation included:

- acknowledging the importance of building relationships with local residents, communities and shop owners

- the importance of creating a positive momentum to the project, for instance through the use of photography and other creative outputs

- understanding how repurposing existing structures can positively contribute to the realisation of net zero aspirations.

Research and insight allows us to ensure there that is focus. It also raised issues that we were otherwise unaware of

Exeter City Council Officer

Deliver: Testing prototype solutions

The final step in the design process relates to prototyping and testing. By encouraging controlled and early failure, prototyping enables teams to test and tweak solutions before committing and going full-scale. In addition to helping manage risks and keeping costs down, this also allows teams to gather additional insights and consider how to communicate the project to stakeholders.

Different degrees of fidelity can have different benefits: from to storyboards to digitally models and physical mock-ups. The merits of these should be considered on a case-by-case basis. To get started, teams produced project posters as a way to bring their emerging opportunity to life and tell a story that helps present their idea to peers for constructive feedback before further development.

Posters brought together in one place multiple strands of information, including: the main problem statement, the key stakeholders, a summary of the idea, a description of how it works, reflections on why it might fail, a discussion of what needs to be prototyped, considerations on how success will be measured, as well as key milestones, and resources required.

Posters were shared with other teams who acted as critical friends. This in turn enabled the generation of further insights. One participant observed:

Prototyping helped us with proof of concept - an insight for future projects is a clear need to tailor language to particular audiences. The course has already proved to be beneficial as we have secured a funding bid.

Bolsover District Council officer

Another participant agreed, adding:

The prototyping work will enable us to test out project at minimal costs to asses the expected levels of engagement.

Exeter City Council officer

The workshop also included a case study from the Land & Property Lead at Enfield Council. The presentation looked at how the council uses meanwhile-use as part of the regeneration of Meridian Water – a major regeneration programme in North London that will unlock 10,000 homes and 6,000 jobs. The case study related to the new Bloqs development which is an open access workshop for local makers.

Top insights from the presentation included:

- reflections on the importance of reusing existing industrial assets as part of an overarching approach to placeshaping

- how integrating existing business community into the economic and physical regeneration is critical to successful placeshaping

- the importance of providing a physical structure that can act as a safe and welcoming centre for the community in undergoing significant and rapid change.

Prototyping has helped us with proof of concept - an insight for future projects is a clear need to tailor language to particular audiences

Bolsover District Council Officer

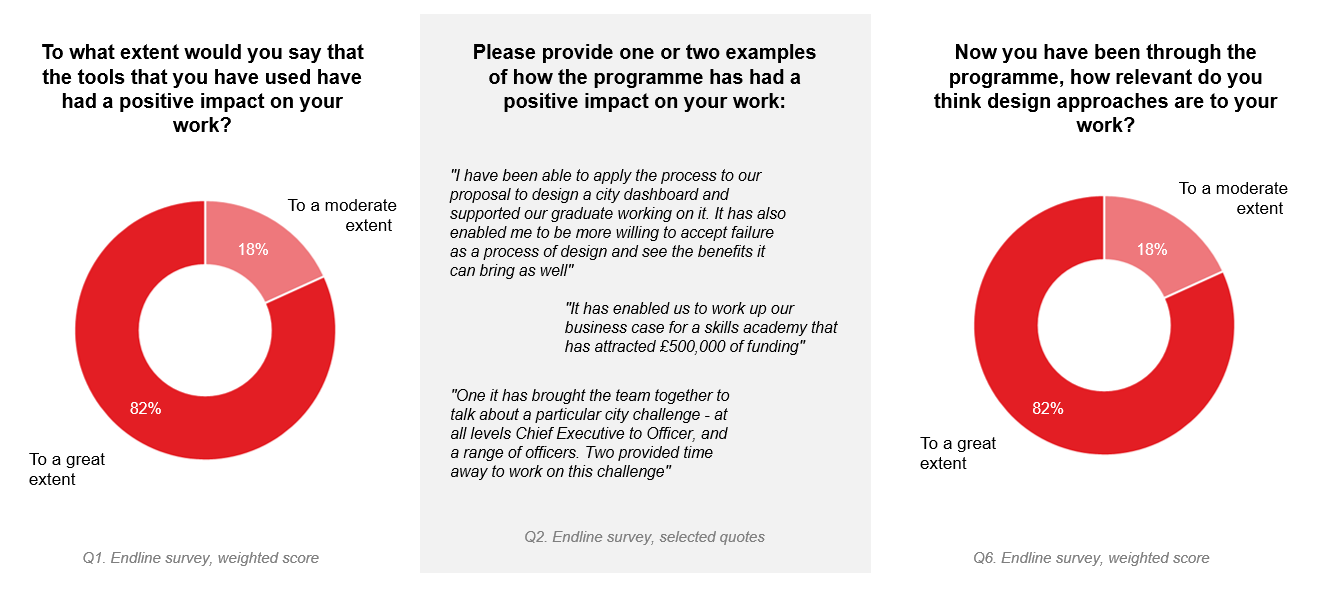

Endline survey: impact of design

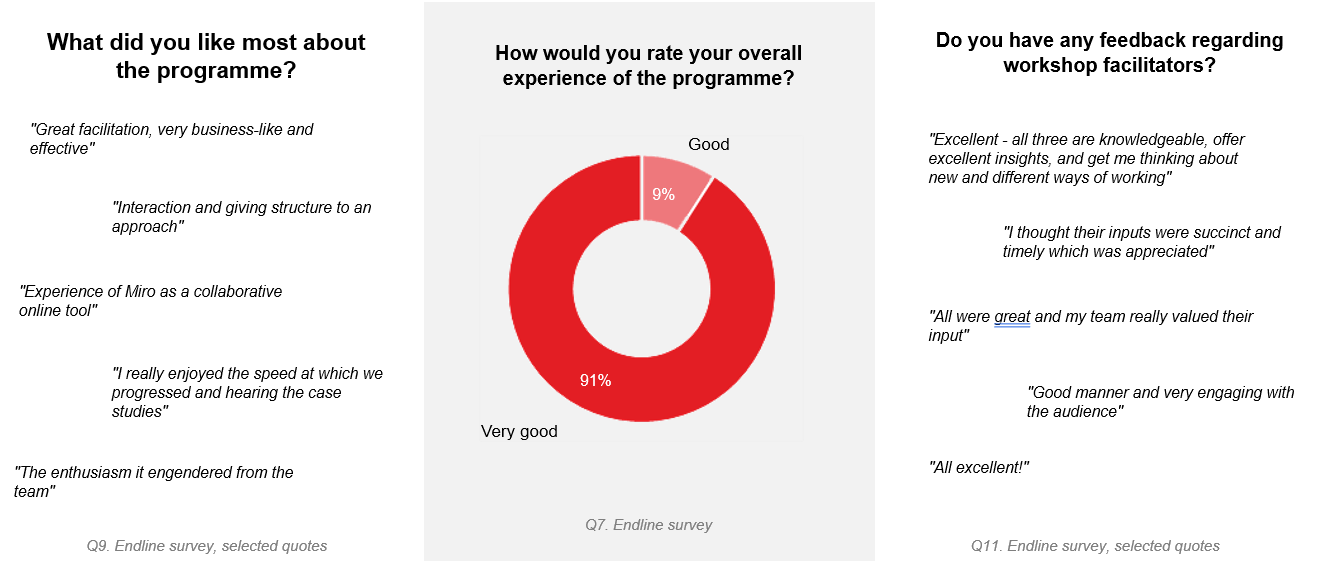

Endline survey: experience of programme

Looking ahead

The tools will help us formulate future project briefs. The course has already proved beneficial as it has helped us secure a funding bid

Bolsover District Council Officer

Levelling Up for a regenerative future

Skills and economic growth play a key role in the Government’s drive to level up the regions, support talent, and transform the UK economy. Too many towns and villages have been left behind in recent years — experiencing concurrent waves of economic stagnation and socio-cultural decline — and it is critical that these challenges are addressed head on.

Design can be a key driver of economic growth and levelling up. As our Design Economy research shows, businesses who invest £1 in design receive £20 in return on investment, and people with design skills are 47 per cent more productive than the UK average. Unfortunately, these economic benefits are unevenly distributed with the design sector largely focused around London and the South East. By investing in design training in authorities across the regions, Government can therefore support local economies and help raise productivity and output.

Design skills are not just beneficial to businesses and SMEs, they also provide genuine value in the public sector. As the Design Skills programme shows, there is a real appetite in local government for learning and adopting strategic design techniques. What this programme – and previous programmes delivered together with the Local Government Association – demonstrate is how design can help authorities come together with local stakeholders to co-create and begin implementing bold visions for the future.

It is critical that Levelling Up does not take place at the expense of the planet. We are living through a climate emergency and measures put in place to support local economies must be counterbalanced by regenerative interventions and the exploration of circular economy principles.

As the UK strengthens its efforts to reduce emissions and mitigate the impact of climate change — and as councils look to increase skills levels, build civic pride, and retain local talent — efforts to level up must therefore be matched by investments in regenerative practices and communities.

We are pleased that the teams participating in the Economic Growth Design Skills programme have focused on forward-looking projects such as the development of net zero research hubs (Bolsover District Council, Exeter City Council), and thoughtful regeneration of the built environment in the town centre (Darlington District Council). However, there are other opportunities for councils to lead on the creation of a regenerative future in line with Design Council’s mission to Design for Planet.

It is for instance an opportunity to explore ways to secure more localised – and sustainable – forms of food production and distribution. Transitioning to a net-zero food system will require significant investment and behaviour changes – including in what we consume and how we produce – and councils are well-placed to lead the way on these transformations.

Another opportunity is for councils to explore ways to make towns and cities more resilient. Climate resilience can be defined as the capacity a town or city has to adapt and cope with the adverse effects of global warming, and to help reduce further harmful transformations. It will require the fundamental re-design of towns and cities and how they function – from energy and water supplies to surfaces, building materials and community engagement with nature – and this work should start now.

In addition to creating new jobs, implementing a climate resilience agenda can furthermore contribute to the creation of better health conditions for communities, whether these relate to physical or mental health. Sustainable modes of transport, accessible green spaces, reduction in toxic fume levels. These are all benefits that potentially flow from a more considered approach to how we plan and shape places.

Taking a triple bottom-line approach to levelling up – factoring in economic, social and environmental forms of capital and dividends – can be a helpful way of framing the issue. Conceptualising levelling up in this way can help not only drive growth and well-being but also support a regenerative future for all.

For more information about the Design Skills for Economic Growth Programme please contact [email protected]