Introduction

Councils provide over 800 different services to their communities and the decisions they make affect the lives of their residents. Local democracy is strongest when there are high levels of civic representation, where citizens voices are heard and taken into account in public policy and local decision-making. However, not all individuals in society feel they can participate equally in the civic arena. As a result, certain groups are underrepresented in formal political activity and wider civic spaces. Addressing issues of underrepresentation is key to ensuring that councils can reflect and address the needs of their communities.

There is a long tradition of councils working closely with the Voluntary and Community Sector (VCS) to respond to the needs of local communities in emergencies and the long term and improve outcomes for residents. The VCS can perform a vital function as local connectors, strengthening links between the council and residents and using creative methods to ensure that diverse voices are present in local decision-making.

Civic participation is the act of engaging in local civic activities. Without good participation from all parts of the local community, civic representation cannot be achieved. Civic participation can range from the highly formalised act of voting for local representatives or standing for office to everyday actions like responding to council announcements on social media.

This research focuses on how councils can work with their local VCS to improve civic participation of underrepresented groups as a stepping stone to good civic representation and enhanced local outcomes.

Background and methodology

The Local Government Association (LGA) has prioritised ‘Strong local democracy’, including supporting councils to explore ways of engaging with their local community and voluntary sector in local service delivery, enhancing places and local decision making.

The LGA commissioned this research from Social Engine to gather good practice around how councils partner with local VCS organisations to engage underrepresented groups and promote the benefits these partnerships produce for councils and communities.

The project aimed to capture existing and emerging practice from councils across the country through a series of in-depth stakeholder interviews. The full list of research participants can be found in Appendix A. It also aimed to contextualise these approaches through a brief overview of the available academic and practitioner evidence.

Civic participation: a review of the literature

There is considerable evidence available around civic participation and local partnership working between councils and VCS organisations. A brief desk review of previous academic and practitioner evidence produced some clear areas of interest for those trying to improve civic participation. The findings are summarised under the following questions:

2. What are the barriers to civil participation?

3. Why do people engage in civic participation?

4. What is the impact of civic participation?

5. How common is civic participation?

6. What do we know about who engages in civic participation?

7. What has the impact of COVID-19 been on civic participation?

8. What frameworks and models exist for civic participation?

What do we mean by civic participation?

Civic representation is the concept that people can participate in democracy, no matter their educational, career or cultural background and communities feel heard and represented through democratic structures and processes. Civic participation is a supportive factor without which representation cannot be achieve. It has no single definition and was widely defined by Adler & Goggin as "involvement in the life of a community in order to improve conditions for others or to help shape the community's future."

Others have been more restrictive in order to categorise and analyse the civic activity of the population. For example, the Community Life Survey – central government's sizeable national household survey of adults aged 16+ in England – differentiates between three aspects of civic involvement:

- Civic participation – wider forms of engagement in democratic processes, such as contacting an elected representative, taking part in a public demonstration or protest, or signing a petition

- Civic consultation – active engagement in consultation about local services or issues through activities such as attending a consultation group or completing a questionnaire about these services

- Civic activism – involvement in direct decision making about local services or issues or in the actual provision of these services by taking on a role such as a local councillor or school governor.

This categorisation is useful for identifying and describing trends over time, but with such restrictions they cannot capture the full breadth of civic activity. The variety of activities citizens involve themselves in is ever-increasing, ranging from political action, charitable participation and volunteering to behaviours that make a statement about the society they want to live in, like boycotting particular brands or products. The growth of online opportunities has also impacted civic participation, with social media and online tools available to help mobilise large numbers of people worldwide. The concept of ‘clicktivism' – the act of engaging in online activism by expressing support or opposition to particular issues online – has lowered the barrier to participation but has divided opinion as to whether it constitutes genuine, meaningful engagement.

Is clicking 'Like' on Facebook a legitimate form of political participation? Is changing your profile picture or sharing an online article politically meaningful? It is undeniable that such actions can be politically-themed, but whether they amount to what we term 'political participation' remains contentious.

Max Halupka, The legitimisation of clicktivism

For the purposes of this research and the resulting analysis, civic participation is defined as any form of activity which results in individuals being visible and accounted for within the local civic structures, processes and informal spaces. Engagement with underrepresented groups is used as a proxy for improving civic participation.

What are the barriers to civil participation?

Maslow's hierarchy of needs is useful when considering what might stop a person from participating in civic activities. Maslow suggested that essentially until a person's most basic needs, such as housing and food, are met, they cannot be expected to engage at the higher levels of 'self-actualisation'. These higher levels involve developing relationships and realising their potential as individuals. Research conducted by Martela and Pesi found that 'self-actualised people' tended to be independent and resourceful and less likely to rely upon external authorities to direct their lives. Once the more fundamental needs of warmth, shelter, food and security are met, people are more likely to engage with broader ambitions of civic participation.

Accessibility is also a critical factor in facilitating civic participation. According to research into getting women's voices into policymaking, such factors are amplified when seeking to ensure participation across intersecting characteristics such as sexuality, ethnicity, disability and socio-economic status. Accessibility is a broad term and can include a range of different considerations, including:

- what language is used, including British Sign Language interpretation

- accessibility of physical space and location

- time of events that suit workers and non-workers

- expenses, including travel, childcare and compensation for people's time.

Policymakers should also understand that simply engaging with a specific group of young women does not cover the vast demographic, issues, ideas and contributions of the rest (i.e. only engaging with white, middle-class young women, who are most likely to be engaged in politics and leading change, will not be representative of all young women's views).

Participant in RECLAIM, a youth leadership and social change organisation

Why do people engage in civic participation?

According to behavioural science, a specific range of factors might motivate a person to take action or act in a certain way. A critical factor is 'what is in it for them' or the 'why' factor? Considering this question can help us to understand how to frame activities in a way that will motivate someone to act.

Simplification

When something is simple, clear and easy to understand (salient), it increases the likelihood of people acting on it. Evidence suggests that simplification can encourage citizens to respond positively. When things are easy for people to understand and act on – eliminating the 'hassle' or lowering 'cognitive load' – they are more likely to do them.

Social norm

When we think that everyone else is doing something, we become far more likely to do it ourselves. Using a descriptive social norm – examples of role models engaging in particular activities – can effectively encourage compliance.

Intrinsic incentive

Incentives are a very effective way of encouraging people to do something and can be defined in two ways. Extrinsic incentives offer personal benefit and can be used to encourage participation. Intrinsic incentives offer people the chance to do 'the right thing' not for personal gain but for the greater good and the benefit of others.

Messenger

Who we receive a message from can be as important as what that message is, and we will often act if we believe that the person conveying the message is trustworthy. We tend to believe people we have things in common with or if we respect their authority and status.

What is the impact of civic participation?

In their study, Community power: the evidence, Pollard, Studdert and Tiratelli outline the central principle that communities have a wealth of knowledge and assets which, if nurtured by practitioners and policymakers, ‘has the potential to strengthen resilience and enable prevention-focused public services.' Pollard et al. identified community decision-making, collaboration with communities and building community capacity and assets as approaches to achieve community empowerment. They also predicted six benefits from these approaches, including improving individual health and wellbeing, strengthening community wellbeing and resilience, enhancing democratic participation and trust, building community cohesion, embedding prevention and early intervention in public service, and generating financial savings.

The impact of initiatives to build community empowerment and increase civic participation are often small-scale, hyper-local and long-term projects which can be difficult to evaluate using traditional metrics and methods used by public bodies to measure success. Policy measures like the Public Services (Social Value) Act 2012 and Social Return On Investment (SROI) have sought to close this gap by requiring commissioners to consider how they can secure social, economic and environmental benefits. Still, these considerations can sometimes be challenging to measure through recognised processes and using standardised key performance indicators.

How common is civic participation?

Levels of civic participation have remained generally stable over recent years. Figures from 2017 indicated that over 25 per cent of people volunteer formally at least once a month; approximately 20 per cent of people are involved in social action in their local community, and 60 per cent of people participate in irregular, informal volunteering. The rise of virtual volunteering, particularly during the COVID pandemic, has provided flexible opportunities for people who otherwise may not have considered volunteering. Other trends, such have ‘ethical consumerism’, have increased engagement on specific issues.

Turnout to vote, the most fundamental expression of civic participation, has – after a historical period of decline – increased slightly over recent years. However, local government voter turnout remains around one-third of the electorate, except in years when general elections are held on the same day as local polls when turnout increases to around two-thirds of the electorate.

According to the Community Life Survey, other forms of participation in local democracy have seen a slight upturn in the past year. The figures suggest around four in 10 people are involved in civic participation, about one in five in civic consultation and nearly one in 10 participate in civic activism.

What do we know about who engages in civic participation?

Research by Uberoi and Johnston typified politically disengaged citizens as those who do not know, value or participate in democratic processes and identified some groups that were more likely to be disengaged. They found that older people and white people were more likely to be actively involved than younger people and ethnic minorities. However, they also had more negative attitudes toward politics in general, and voter turnout and volunteering among younger people have recently increased against previous trends.

Research from various sources shows a significant gap in civic participation between white and ethnic minority citizens when comparing different forms of participation, including charitable giving, interest in politics, voting and formal volunteering. Although it is possible that cultural differences and the language used to describe volunteering may lead to under-recording of volunteering activity.

Figures from the 2018 census of local councillors shows a clear disparity in elected representatives from an ethnic minority background, with just four per cent of councillors from ethnic minority communities, compared with 13 per cent of the population. There was a similar disparity in relation to gender; only 36 per cent of councillors were women. Sixteen per cent of councillors recorded a long-term health problem or disability, which limited their daily activities; 20 per cent of the population declare a disability or long-term health condition and given the age profile for councillors, 16 per cent actually indicates an underrepresentation. Twelve per cent of councillors defined themselves as not heterosexual or ‘straight’.

Research by Smith and Wang in 2016 shows that socio-economic status and education are strong predictors of civic participation. Those from a higher socio-economic background and higher education attainment are more likely to participate in civic activities than those with lower educational attainment or from more deprived backgrounds. In the 2018 councillors census, 63 per cent of councillors held a degree or equivalent qualification, and only three per cent did not have any formal qualification.

It is possible socio-economic structures in society may prevent certain people from participating in democracy fully and equally. Those with more resources have greater opportunities to participate more in politics, which leads to these groups influencing political decisions. This can reinforce feelings of alienation and disaffection and fuel disengagement behaviours.

What has the impact of COVID-19 been on civic participation?

The response to the COVID-19 pandemic has illustrated how communities can come together to achieve positive outcomes in times of crisis. COVID-19 gave rise to a plethora of mutual aid groups during the pandemic, with over 4,000 groups in the UK, according to Mutual Aid UK. Despite being an unprecedented and challenging time, many people still felt looked after and safe thanks to their communities. ONS weekly research from June 2020 found nearly two-thirds of adults said other local community members would support them if they needed help during the pandemic, three in four said they thought people were doing more to help others since the pandemic, and over one in three had gone shopping or done other tasks for neighbours in that week.

Analysis of Mutual Aid open data and Index of Multiple Deprivation data conducted for Unbound Philanthropy by Social Engine found evidence that mutual aid groups were more prevalent in more affluent areas. Region and urban-rural characteristics of areas appeared to be other factors in the level of mutual aid activity. Rural areas were twice as likely as urban areas to have mutual aid groups. Considerable regional variation was also evident with significantly more mutual aid groups per capita found in Southern regions (London, South East, South West, and the East of England) than in other parts of England.

What frameworks and models exist for civic participation?

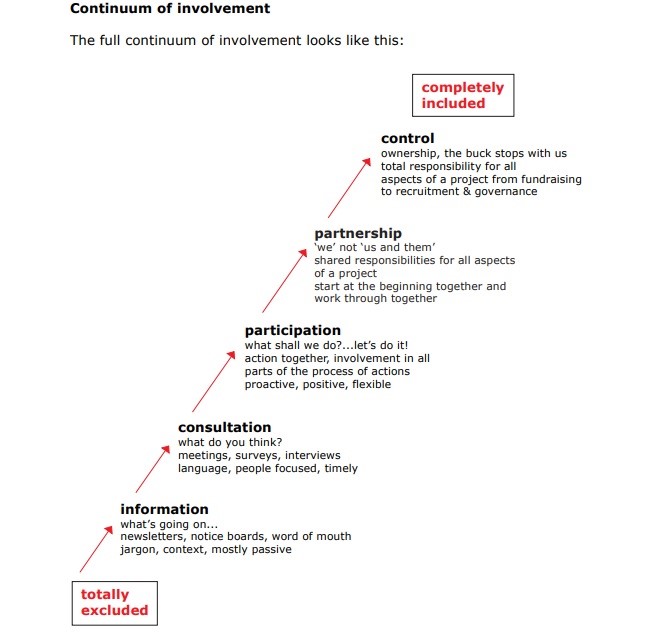

There are several different theoretical models which can be used to classify different types of participation and engagement. Many of these models draw on Sherry Arnstein's 1969 ‘ladder of participation’, which describes eight steps of participation from non-participation through to total citizen control.

Homelessness charity Groundswell UK adapted Arnstein’s ladder into their own ‘continuum of involvement’ as part of their Diversity Toolkit to increase the involvement of homeless people in service design. While the highest level of ‘control’ may not be suitable within the context of civic participation in representative democracy, the continuum recognises the considerable spectrum that exists in the ‘continuum of involvement’. Consultation is one mechanism for residents to have their say – and certainly plays an essential role within a broad engagement strategy. However, it is not the only mechanism, and other approaches that are more participative and partnership-orientated are likely to offer more empowering and meaningful engagement.

The Royal Borough of Kingston’s community engagement framework adopts a similar model to set out a strategic approach to engagement, presenting it as a cycle rather than a hierarchical ladder or a continuum. This framework illustrates how, at any given time, an authority might be engaging in different ways with different groups across all the different levels of participation.

Local approaches, insights and examples

Councils have a long history of partnering and working with their local VCS to respond to the needs of their local communities. In this case, the research team sought out relevant council/VCS partnerships working to engage specific underrepresented groups with a view to increasing civic participation. This section outlines the insights the research team gained around the three research questions below through 14 qualitative interviews with councils and VCS partners (referred to as participants). Findings are set out under each question and supported with relevant examples.

• What impact did engagement with underrepresented groups and enhanced participation have?

• What were the critical success factors for achieving positive engagement and increased civic participation?

What challenges were councils seeking to address?

Before considering what engagement methods were most successful, it was important first to understand what motivates councils to engage underrepresented groups and what challenges they seek to address through engagement.

Initiatives that focused on engaging underrepresented groups arose from a variety of challenges and opportunities. These ranged from a desire to support leadership and civic participation across the whole community to a belief that services would improve by incorporating the views of those who access, or might access, services. Many initiatives were long-standing and reflected a multi-year commitment to improving participation. However, recent events such as COVID-19 and the Black Lives Matter movement have prompted councils to attempt new approaches. These initiatives shared an acknowledgement that lived experience offers valuable insight and value to local decision-making and that people must feel welcome to participate.

People with lived experience hold the key information to improving services, what it’s like living in supported accommodation, what could be improved, key themes about what people like/appreciate/want to see from services and new projects.

Participant, LEAF

Enhancing representation and participation

For many councils, the main aim was to increase civic participation and representation among particular groups and communities. The outcome they sought was to encourage formal and informal civic participation within local democracy and decision-making.

In some cases, historic mistrust between the target group and the council stood in the way of better relationships. Councils described reframing their interactions with the target group using non-traditional methods. For example, Everyday Politics used informal mechanisms as part of their action research project ‘Jam and Justice’ to increase participation in political processes within Greater Manchester. The initiative was based on the photovoice project, using photography as a basis for discussion to understand more about everyday politics. Other projects, like the Youth Independent Advisory Group in Waltham Forest, used peer advocates to convey information rather than traditional council communications channels.

The Young Advisors and subgroup Youth Independent Advisory Group (YIAG) in Waltham Forest aim to bring young people into the heart of decision-making, enabling young people in the area to use their expertise, knowledge and experience to contribute to local decision-making. The groups create opportunities for young people to act as youth consultants in their community, as experts in the place they grew up and live.

Being a Young Advisor and YIAG helps young people build their confidence and skills and gives transferable employability skills. They get two full days of accredited training on public speaking, team building, engagement theory and practice, social action and more. Once they have completed the training, they can undertake paid work as expert youth consultants. Young Advisors (and YIAG) are paid the London Living Wage on a commissioning-based model. Young Advisors have a peer recruitment process, but the YIAG also takes referrals from partners such as the Youth Offending Service, Children’s Social care and other services like Victim Support. While financial incentives are helpful, for many Young Advisors and YIAG, their work and the difference it makes have an intrinsic value that is equally motivating.

One issue that was identified by young people through this process was a lack of confidence in the police, while data showed racial disparity in Stop and Search. Recognising the importance of positive relationships, the YIAG are now co-designing a process with the Community Safety Team at the council to improve young people’s experience of the police, including an independent advocacy service. The YIAG has been part of this project from the outset and is now involved in implementing recommendations from their peer research on the issue through their Streetbase programme.

The Young Advisors programme also helps raise awareness and understanding of local democratic processes and structures among young people, which leads to further engagement and participation. The programme, specifically the YIAG, has been remarkably successful at engaging young people who may not traditionally engage with the council by using peer advocacy rather than relying on traditional council communications and engagement. The increased knowledge and understanding of local democracy has even resulted in a Young Adviser standing for election, demonstrating the potential of the project.

Improving outcomes and services for underrepresented groups

Many councils aim to engage underrepresented groups and increase their participation as a way to improve outcomes and services that they provide. Participant councils highlighted the importance of the voices of those with lived experience feeding into all stages of service design and delivery. By incorporating the perspectives of current, former and potential users of services, many councils sought to ensure that the design and delivery of services were more responsive to people’s needs and aspirations.

Some councils were able to identify specific outcomes they wanted to improve and focus their efforts on those most affected. For example, councils working with MiFriendly Cities (funded by Urban Innovative Actions) aim was to make cities more migrant-friendly and address a wide range of social and economic issues, including barriers to employment, health, active participation, and empowerment. The project brought together eleven public, private and voluntary sector organisations across the West Midlands – including Wolverhampton, Coventry and Birmingham City Councils – with the ambition of creating “a region built on a spirit of solidarity”.

Other examples were more general. Challenging relationships between specific target groups and public services heightened community tensions and reduced participation. Lack of input from prospective service users meant that services were underutilised and inefficient as they did not met the need of the community.

Tackling root causes and historic issues

For some councils, efforts to raise civic participation and engagement was part of wider prevention efforts, seeking to tackle the root causes of particular challenges rather than responding to the downstream effects that arise from them. They saw civic participation and placing those with lived experience at the centre of decision-making as a key pillar of developing new ways of working.

Several councils, in areas including West Cheshire, Leeds, Morecambe Bay and east Surrey, have developed Poverty Truth Commissions as a response to poverty and social exclusion in their communities. Many others are in the process of establishing them. Poverty Truth Commissions aim to tackle the root causes of poverty and to alleviate poverty through the engagement of those with lived experience.

"Poverty Truth Commission puts people with lived experience at the front and centre of the approach."

Participant, West Cheshire Poverty Truth Commission.

The process helps those with lived experience, known as ‘Community Inspirers’, develop the confidence to articulate their stories and experiences and share them with civic and business leaders. The process links together those with experience to those with the power to address issues, barriers and inequality. For the councils undertaking Commissions, bringing these voices into decision-making through coproducing reports, workshops and meetings represents a step-change from previous engagement approaches and aims to break down barriers to proper understanding.

The journey is about bringing testifiers and leaders together. At the beginning, they are apart, but by the end, there is no ‘us’ and ‘them’. Participant, Poverty Truth Commission.

It can be challenging for councils to instigate and maintain an ongoing relationship with communities. Sometimes specific events create a moment in time that allows communities to begin conversations and address issues that have not been addressed previously. The Black Lives Matter protests, and the evidence that COVID-19 has had a disproportionate impact on Black and ethnic minority communities are clear examples.

Birmingham City Council recognised that there were voices in the community that were not being heard, with particular groups underrepresented in civic spaces. COVID-19 and Black Lives Matter (BLM) highlighted systemic inequalities. The council saw this as an opportunity to develop a new approach to address these issues more strategically.

"The pandemic has given us a moment to step back and not impose knee-jerk responses, and allow us to work through this with our communities. Ultimately we want to tackle structural systemic inequalities, make a lasting change and make communities part of the ambition."

Participant, Birmingham City Council.

The council formed a partnership with Operation Black Vote (OBV) – a non-partisan political campaign that seeks “to inspire BME communities to engage with public institutions and address persistent race inequalities.”

The broad aim of the collaboration was to engage underrepresented voices in formal decision-making spaces such as school governors and elected councillors and wider political engagement. Fifteen individuals from Black and ethnic minority backgrounds were invited to participate in a mixture of observation and training sessions across various areas of public life, including education, policing, the criminal justice system, health, the voluntary sector, and local government. The programme also included a learning seminar looking at the importance of civic activism and race, equality, and Black and ethnic minority representation. The process is designed to give participants insight into public bodies' systems and procedures and equip and motivate them to engage in public life, civic engagement, and community affairs.

"We want better representation of underheard voices in civic and professional spaces."

Participant, Birmingham City Council.

Birmingham recognises that tackling inequality is a long-term agenda. They are working together with OBV towards the next phase of the project and building lived experience into its design using an inclusive, participatory model of engagement that can adapt to the communities involved.

"Voices are much bolder and stronger coming out of the pandemic – the pandemic has given [them] the cover, and safety to have those conversations."

Research participant, Birmingham City Council.

What impact did engagement with underrepresented groups and enhanced participation have?

Councils referred to various benefits and positive impacts for underrepresented groups' lives and local decision-making, service design, and delivery. In many instances, these improvements resulted in wider benefits through improved efficiency, enriched democratic processes and increased skills and capabilities across localities. Benefits derived from enhanced participation were seen at an individual level, at institutional and organisational levels, and impacted the community as a whole and target groups.

Empowering individuals

Participants reported that improved civic participation empowered those involved – giving them confidence, knowledge, understanding and a strengthened sense of efficacy. This effect was not confined solely to underrepresented groups; council officers, elected members, VCS staff, and volunteers involved in the process also benefited. Several interviewees spoke about their empowerment to speak up and share their views and experiences.

It is important that testifiers feel part of a community where their experience is taken seriously by others who share similar struggles, and recognise a commitment as they begin to do that, that their voices and experiences will be listened to. Participant, Poverty Truth Commission

While the idea of empowerment can be hard to define and measure, for those who experience it, the impact is tangible and significant. This is an integral part of the process – people need to feel heard, be empowered to 'speak their truth', and feel valued before they can start to move forward. Only then can they engage with things that the council or others might want to discuss, such as solutions.

Building bridges and cohesive communities

Councils play a key facilitating role within local communities, but sometimes they can be difficult for the public to understand. In partnership with VCS organisations, councils can create the necessary environment for people to be heard by those with power and influence. This approach creates new connections within communities and provides the time and space to build relationships, fostering understanding, trust and tolerance. The benefits of this are two-fold; underrepresented individuals and groups feel their truth is being valued, while gaining an improved understanding and insight of civic institutions, elected members and those delivering services. Ultimately this improved awareness on both sides strengthens connections, dispells myths, and improves cohesiveness within communities.

The Southwark Stands Together listening exercise was an important and emotionally charged experience for those who participated. It encouraged residents and stakeholders to share their experiences of racism, discrimination, and inequality in a listening environment and invited them to prioritise areas for change and posit solutions. This engagement took place at a sensitive time only weeks after the death of George Floyd and in the middle of a pandemic. The online survey and group session allowed people to reflect on previous experiences and the impact recent events had on them. As a result, a parallel stream of the project was developed, focusing on healing and reconciliation, bringing people from different ethnic backgrounds together and focusing on lived experience, giving them a platform and ensuring their experience was heard.

Logistical and capability barriers can increase the sense of separation between councils and communities, leading to divisions and a sense of ‘otherness’ which undermine cohesion and integration. In Birmingham, women with English as a second language faced multiple barriers to participation. Their lack of confidence in their use of the English language made it hard to express their opinions and meant they were unaware of opportunities. Council staff facilitating conversations created opportunities that were relevant and accessible and improved their conversational English language skills, enabling them to gain greater confidence and feelings of efficacy.

A number of women said how empowered they felt with just me sitting in the room.

Participant, Birmingham City Council

Improved evidence, insight and understanding

Understanding the needs, aspirations and ambitions of underrepresented groups based on their lived experience can significantly enhance local decision-making. Councils reported that effective engagement and participation from a broader range of the community increased insight and understanding, which enhance strategy development and service design.

The qualitative nature of the majority of engagement approaches contrasts with typical data collection and evidence processes. Hard data and clear metrics are easier to gather, analyse and describe but do not reflect the fullness of service users and residents reflections. They can fail to bring out ‘softer’ outcomes like empowerment and confidence, which are equally important. This gap is a significant challenge when assessing the efficacy of support and services and making decisions about service provision. Thus, there is a challenge to reconcile the tendency to operate in ‘hard data’ with the value of storytelling.

A VCS partner can play an important role in filling this gap. Partners already well established in a community can help them make sense of council processes so they can engage independently and assist the council in developing appropriate and meaningful targeted engagement opportunities. As a trusted intermediary, VCS partners can also 'shine a light' on emerging issues and bring them to decision-makers attention. From a council perspective, the relationship gives them access to valuable insights from the community, which improves the evidence supporting decision-making.

The MiFriendly Cities project, funded by Urban Innovative Actions, aims to make cities more migrant-friendly, addressing a wide range of social and economic issues, including barriers to employment, health, active participation, and empowerment. The project brought together eleven public, private and voluntary sector organisations across the West Midlands – including Wolverhampton, Coventry and Birmingham City Councils – with the ambition of creating “a region built on a spirit of solidarity”.

The MiFriendly Cities project bridged the gaps between councils and grassroots organisations via intermediary organisations. These facilitated relationships allowed underrepresented groups and organisations to flag issues hidden previously.

Migrants at Work, a grassroots group championing labour exploitation and discrimination of migrant workers, had been identifying gaps and inconsistencies between immigration and employment for some time without gaining any traction. MiFriendly Cities project and Coventry Council listened to the groups' concerns and supported their work. They provided a platform to brokered and foster relationships between the group and other partners, including Central England Law Centre and local migrant centres, which meant the group could have more of an impact and begin to address injustices experienced by local migrant workers.

Given the feelings of powerlessness and a sense of injustice that characterise the experience of many underrepresented groups, having some of these issues addressed can have a profound effect on wider engagement and a sense of efficacy often seen among those who are already active in civic participation.

Those with lived experience are often better placed to gather evidence and insight from within communities than professional researchers or council officers alone. In Oxfordshire, the Lived Experience Advisory Forum (LEAF) collaborated with Crisis to train LEAF members as researchers to undertake in-depth interviews as part of a peer-led research project. They encountered challenges around sharing data about homelessness service provision and GDPR restriction as subjects were often transient and frequently crossed administrative boundaries. LEAF overcame this by seeking informed consent from homeless people to share their data between providers and neighbouring authorities, where it was in their interest to do so. The study showed flexible approaches can make data-sharing possible.

Finally, sometimes it is assumed that some groups are not inclined to engage with local democracy. While some individuals may actively choose not to engage, it is less likely that whole groups are naturally disinclined with no reason. Participants reported that underrepresented groups might not engage with local democracy because of a lack of insight into council structure and processes or a feeling that these structures are inaccessible, irrelevant and hard to influence. For example, the MiFriendly Cities project recently worked with a Congolese community who did not know they had the right to vote or how to vote or that they could participate in council consultations. The MiFriendly Cities project invested in an African French Speaking Community Support group that ran an active participation project with the support of MigrationWork. The group supported individuals to participate in civic activities like registering to vote, accessing information to understand their rights, and meeting political candidates.

Changing procedures and ways of working

Engaging underrepresented groups helped several councils identify barriers to participation, which arose as an unintended consequence of usual ways of working. For practical and rational reasons of management efficiency, councils organise services and other activity across different directorates and departments. Each department comes with its own working practices and culture, even within an overall corporate identity. However, for many underrepresented groups – and indeed citizens more generally – these divisions do not reflect their day to day lives and the way they interact with the council.

In 2009, the first Poverty Truth Commission was launched in Scotland, based on a belief that the wisdom, experience and understanding of people who struggled against poverty were vital in making decisions about poverty.

Cheshire West and Chester Council were the first councils to establish a Poverty Truth Commission in 2017 and ran two Poverty Truth Commissions were run between 2017-2020. They brought together people with lived experience of poverty in the area (‘community inspirers’), people with influence in the area (Civic & Business Leaders) and young people (Young Inspirers). The aim was to tackle the root causes of poverty; this was explored through regular meetings where participants identified the topics for discussion and shared stories and experiences. After the second Commission, 100 per cent of the participants reported increased understanding of others, respect, motivation, friendship and inspiration. Participants in the commission bought into the process, building trust and forming relationships, which led to minimal drop-out rates. The commitment of people in positions of influence helped build relationships and trust with some of the volunteers who were somewhat wary of the people in authority due to previous negative experiences.

"Local authorities begin to see how this way of working allows them to do their work more effectively."

Research participant, Poverty Truth Network.

Rather than running a third commission, the council now wants to embed this approach across other parts of the council, demonstrating a change in how they engage with residents, with increased opportunities to influence decision-making. The council has set up a Poverty Truth Advisory Board, which includes people with lived experience; a Community Inspirer also co-chairs it. The board report to Cabinet to shape anti-poverty strategy. They aim to increase co-production across other council services due to the success of the WCPTC2.

In some instances, councils can benefit from examining and reconsidering how they collect and interpret data to understand lived experience better. Several councils highlighted the benefits of a lived experience approach, valuing personal storytelling as a critical outcome from the process. By drawing on the evidence gathered by charities and community groups, councils can incorporate additional richness to policy evaluation and enhance understanding of local outcomes for all communities.

The deficit that many leaders have is not that they don’t have access to the quantitative data, but they don’t have access to the qualitative that informs or enriches that data. You are running the risk of exacerbating or wasting funds.”

Participant, Poverty Truth Network

Improved efficiency and cost savings

Cost savings are rarely the primary objective for councils. However, councils reported that increasing participation and engagement activity can help with the alignment of services to the actual needs and aspirations of those accessing them. This improves their effectiveness in terms of addressing need and avoid the inefficiencies of underutilisation or displacement of need to other services.

In Fenland, effective engagement with Gypsy, Roma and Traveller communities by the council enabled them to identify and articulate their own needs and aspirations. This led to effective solutions to site management issues and improved on-site provision. This activity resulted in practical benefits, including - improved quality of life, greater community cohesion and integration, breaking down misconceptions and stereotypes and reducing isolation through stronger and broader social networks and community connections. In the long-term, this also created savings through improved health, education and employment outcomes.

We help them integrate at their own pace making sure the right support is in place to make that happen.

Participant, Fenland District Council

Sometimes the financial benefits are more tangible. As part of the second Cheshire West and Chester Poverty Trust Commission mentioned earlier, the council used the Social Return on Investment methodology to establish that for every £1 spent on the Commission, there was a return of £9.17 due to improvements to social housing provision in the area. They calculate this has the potential to double once these changes are rolled out to other housing providers.

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the risks and impacts of social isolation. Improved engagement and participation can foster links and social connections within communities, strengthening community infrastructure, and reducing and preventing isolation and loneliness. Councils had to work efficiently to respond to a huge increase in immediate and long-term need.

The London Borough of Newham worked closely with partners in the public, private and voluntary and community sectors to deliver the #HelpNewham programme of essential support, including food, supplies, prescription delivery services and befriending service to residents in vulnerable circumstances. A recent evaluation of the programme found significant evidence of recipients, volunteers and professionals feeling more strongly connected to the community and less isolated.

The initiative was delivered at scale and speed, and both the council and the community benefited from the programme. The council was able to meet the unprecedented demand for support by utilising over 1000 volunteers and their partnerships with faith, voluntary and commercial organisations.

#HelpNewham presented an opportunity for residents to engage with the local community, helping people feel connected to the outside world during the lockdown, a time when the risks of separation and loneliness were particularly acute. As well as reducing isolation for the volunteers, this engagement also positively impacted residents who benefitted from the interactions on delivery or upon receiving befriending calls.

In some instances, partnerships with VCS organisations can leverage additional external resources into an area. Funding from the Arts Council England and other funders enables councils to access activities that might otherwise be beyond their own budgets and amplify their own cultural funding while generating new engagement with diverse communities.

Global Streets is a consortium of arts organisations that work with councils in 12 English towns and cities with low levels of cultural engagement. Funded primarily by Arts Council England and other grant funders, Global Streets works by securing effective local partnerships with arts organisations, leaders, and the council and providing funding that might otherwise be beyond council budgets. They provide international arts programming tailored to engage diverse communities wherever they perform.

"We’re a community where a lot of cultures live together, so it’s good to enjoy everybody’s culture."

Audience member, Barking and Dagenham.

Jane, a community centre manager from Woolwich, was inspired to participate in ‘Rise!’, a Global Streets production that was adapted for various communities across the UK during 2018. She worked with other local residents to celebrate the contributions of women and non-binary people through a series of exhibitions focused on the Suffragette Movement. Global Streets projects in the area have opened up new opportunities to engage local people from the estates served by the team from Woolwich Community Centre.

"As I’ve become more involved in this project, I’ve learned more about the amazing things that are happening in this area, and it’s really moved me."

Global Streets Ambassador, Woolwich.

Global Streets has developed a track record for delivering participative international outdoor arts, and with a nationwide network of ambassadors – local advocates who are more engaged in their communities' wider civic life – are uniquely placed to secure participation amongst those who may have felt excluded from other initiatives. For example, in recent years, Hounslow Council has worked alongside the team to develop innovative ways to engage Hungarian and other Eastern European communities in civic life. It is a picture reflected in many other locations where councils have identified the need to ensure the full diversity of the community can secure routes into social and civic participation.

What were the critical success factors for achieving positive engagement and increased civic participation?

Councils use varied approaches to increase civic participation, reflecting the diversity of different communities and their particular circumstances. However, it is possible to look across these examples and pull out those factors in common, which participants described as critical to achieve meaningful engagement.

Recognising difference and using varied engagement tools

To increase participation of underrepresented groups, the council must acknowledge that individuals within these groups are not homogenous, recognise internal diversity and act accordingly.

Communities are comprised of multiple perspectives and define themselves in a myriad of different ways. Particular groups defined using official demographics are likely to comprise diverse attitudes, values, behaviours, and experiences; individuals linked by similar characteristics may have more differences than similarities. Many groups overlap, and it is important to consider the intersectionality of different issues rather than making assumptions based on superficial information. It is also important to consider the range of ways different people might prefer to engage.

Every case and every issue are different. Everyone was in the position they were in because of different factors. But no matter their position, they all get pushed down a similar tube, even if the reason they are in that position is different.

There is no recognition of this.

Research participant, Poverty Truth Commission, Leeds City Council

Different approaches are needed to engage different people (even within specific underrepresented groups). Digital engagement opportunities will appeal to some groups; others will be digitally excluded. On the other hand, relying on traditional methods of engagement can be inaccessible.

There are specific circumstances where a shift to one kind of engagement or another will be necessary. For example, the infectious nature of COVID-19 necessitated that engagement with communities shifted to online or remote platforms only for a period of time, and social distancing has constrained how people can gather. Engagement can still take place under these circumstances and, in some cases, has increased the volume of participants; council meetings have been better attended by the public when taking place virtually than when they were required to meet physically.

However, the pandemic also highlighted the challenges of digital exclusion among those who are less comfortable using technology, don’t have easy access to the internet, or prefer to participate face-to-face. One size fits all engagement methods cannot be fully inclusive and will fail to capture the range of opinions and experiences. Instead, councils can appeal to residents with different needs and preferences by adopting a range of engagement methods.

Southwark Stands Together held a series of digital meetings and two outreach face to face engagement sessions as part of a listening exercise to hear from Black and ethnic minority communities about their experiences of racism, discrimination and inequality. Continuously refining and adjusting the approach to engagement was critical to ensuring continually relevant content. The council secured a high level of engagement with people who had never previously spoken to the council on topics that had not previously been discussed through a listening exercise. The council uses a multi-layered engagement approach to facilitate a continuous conversation with key stakeholders and residents, allowing them to shape the narrative around the approach and solutions. Holding virtual meetings helped increase engagement among those who might not have been inclined to attend a meeting in person, as people could join from their living rooms, underlining the importance of ‘convenience’ to effective engagement.

Successful engagement tends to proactively engage people where they are already – rather than attempting to invite them to where is most convenient for a council. There is no single method that will be effective with everyone, hence the need for mixed, multiple modes and opportunities for people to get involved.

Meetings held virtually exclude those who are not digitally literate or can’t afford phones or laptops. We can’t have an over-reliance on online forums alone. We need to think about how we can inclusively engage quiet, crucial voices in discussions to shape policy.

Participant, Birmingham City Council

Establishing relationships and trust

Councils report that trust and relationship-building were crucial to the success of approaches taken by councils and their partners. Without trust, the prospects of effective engagement are greatly diminished. Negative perceptions of public institutions can impact trust, and relationships can be damaged by ‘consultation fatigue’, which can lower expectations on all sides.

Agreeing on a shared sense of purpose and common objectives can help develop relationships and new ways of working. In the long term, fulfilling obligations set out at the beginning of the relationship can help demonstrate commitment to those objectives on both sides and create trust between partners.

A good relationship cannot be formed overnight; there needs to be an investment in and commitment to the relationship - and the communities need to see this and recognise this. We can communicate on a level playing field because we understand each other.

Research participant, MiFriendly Cities

Councils articulated the need to be bold; to work with and through established and new partners, and demonstrate their commitment early on to act as a visible symbol of a new way of working. Establishing credibility with VCS partners who hold sway in target communities can send a signal to that community and draw previously unwilling voices into the debate. The Southwark Stands Together project is again a good example; participants expressed that they finally felt valued and would not have felt comfortable or had the confidence to share their experiences without first establishing a positive relationship with partners, including the council.

Coming together as one group is THE critical success factor.

Research participant, Leeds Poverty Truth Commission

Transparency and openness

Being transparent and honest about the engagement process and the constraints and opportunities was a common feature of successful approaches. There are, inevitably, certain limitations – whether legal, financial or logistical – that councils need to operate within. Effectively engagement approaches were realistic and open about the capacity to deliver and avoiding overpromising. Clear parameters help build trust and confidence in the process and manage expectations about the scale and pace of change.

The engagement process can still become derail even after clear parameters have been agreed if the desired change is not delivered at a sufficient pace or if people feel they are not being heard. Early demonstrations of how the views and voices of those with lived experience have informed decision making can act as a symbol of the council’s commitment and give underrepresented groups confidence in the process. For example, if parameters need to change, this should be decided transparently after seeking the views of all relevant parties and communicated to stakeholders openly.

Meaningful engagement is not a linear process, and councils and the communities involved may need to ‘hold their nerve’ and expect there to be ‘bumps’ along the way. The challenges that arise are less important than how councils, their partners, and the communities involved work together to respond to and overcome them.

Finding solutions to barriers

Traditional ways of working can create barriers to engagement, and overcoming these is a central factor in effective engagement. Similarly, new ways of working introduced to engage underrepresented groups inevitably 'bump up' against standard processes and defaults. Overcoming these challenges is not insurmountable but requires sufficient resource to drive engagement activity and creativity to find solutions.

In Waltham Forest, YA and YIAG were financially incentivised, which initially posed a challenge as the councils HR and payroll team were not used to employing young people under 16 as casual workers. However, support from the Leader and the Chief Executive (among others) from the outset meant that officers were supported from the top of the council to get past barriers in the system and make the incentives work.

Similarly, traditional behaviours and practices among council officers and working culture can inhibit effective engagement. Council leaders set the tone for officers working with VCS partners and underrepresented groups to find appropriate ways of working. Working culture can either inhibit creativity and flexibility or establish a culture of permission to experiment and test new approaches, which are required to adapt and respond to emerging needs and preferences.

[There are] Pros and cons of being led by a council – has the stability of resource of a council rather than VCS but doesn’t always have great flexibility.

Participant, West Cheshire Poverty Truth Commission

Engagement invariably takes time, effort and a lot of resourcing to have a meaningful impact, which can be difficult for councils where such resources are constrained. Good engagement and increased participation can result in considerable downstream savings and more sustainable engagement going forward, but it requires an upfront investment as with most preventative measures. Investment can be in form of council funding or capacity, external funding, and capitalising on in-kind support from VCS partners and volunteers. The most effective approaches view engagement as a long term process acknowledging that results may not be immediately apparent and are flexible on how this investment can be deployed.

It is important in terms of working with the migrant communities that the funding criteria could be flexible and adapt to needs of communities as they saw it changing because the ground is always changing.

Participant, MiFriendly Cities

Preconceptions and cognitive biases can affect the dynamic of the relationship and result in unintended barriers to engagement. The language used and how to frame challenges and opportunities can significantly influence how people respond to attempts at engagement and whether they are willing to participate.

We talk about ‘deprived areas’, though testifiers say ‘my area isn’t deprived’; we have to be conscious of who we are talking to.

Participant, Leeds Poverty Truth Commission

Finally, it is also important to recognise that councils, like communities and groups, contain multiple attitudes and behaviours and cannot be regarded as single entities that think and act as one. No one person or group has a monopoly on being 'right' all the time. An openness to challenge and a willingness to reflect and learn can create a better environment for participation for groups that have previously felt excluded.

The overwhelming myth is that those who struggle against poverty don’t have the ability to live resilient lives or to develop solutions to injustice and poverty. While there is a temptation for those struggling against poverty to believe that public service doesn’t care about the predicament of those who are subject to injustice.

Participant, Poverty Truth Commission

Bridges and boundary spanners

Councils typically know where the gaps in knowledge, services and engagement are. However, a third party can help to advise and embed solutions to address these gaps can be extremely beneficial. This third party take on a ‘brokerage’ role, known as ‘boundary spanning’, and use their skills, knowledge and presence to connect with the community in terms that resonate with underrepresented groups while ensuring the engagement is reciprocal.

Councils do not necessarily have the right capacity and expertise to work across all areas of integration and community cohesion. Fenland has one of the largest GRT communities in the country, and the council has developed several different strands to support engagement with this community.

The council invested in a dedicated liaison officer to ensure that engagement was handled sensitively and obtained grant funding to deliver projects to support integration and community cohesion in partnership with VCS groups. Over time, this has helped develop a strong and effective relationship based on shared understanding and trust.

One project involves 12 Community Champions who relay important messaging from the council in relevant community languages. The Champions have been invaluable in tackling misconceptions and misinformation during the pandemic resulting in the increase in vaccination uptake.

A Diverse Communities Forum brings together key stakeholders from communities and VCS organisations and faith communities, housing providers, and local business groups. Members work together to share knowledge on key issues, use collaboration to align activity and avoid duplication. The forum provides a platform for co-operative work on funding bids, with the council supporting partners best placed to deliver in their efforts to take forward ideas for projects.

Establishing a good working relationship and a forum for collaboration has benefited both the council, who avoid incurring high enforcement costs and pre-empting changes in demand, and communities by ensuring they the opportunity to express their needs and aspirations directly to the council and other partners.

Initiatives like the Diverse Communities Forum ensure that the council is continually kept up to date with changes, attitudes and experiences within their communities. As a coordinator of the forum, the council's role means they are ideally placed to suggest, respond and support projects while listening to their partners who are in the best position to take the lead.

"We must be in a position to hear feedback and address feedback.”

Participant, Fenland District Council.

VCS organisations working with particular communities and underrepresented groups often play this role and can specifically support councils looking to improve civic participation. Participants particularly highlighted the importance of working with smaller grassroots organisations with strong connections and reach into particular communities.

Friends, Families and Travellers adopt this boundary spanner role, playing a crucial role in encouraging and supporting community representatives to attend residents’ meetings and engage with processes. Their knowledge and understanding of councils mean they can advise them in their engagement approaches and develop more effective ways of working.

We have the trust of the communities, and a bit more authority to push local authorities in terms of repairs, decision making, transparency.

Participant, Friends, Families and Travellers

Despite the hugely effective role that boundary spanners can play in connecting disparate groups, they should not be regarded as a panacea for effective engagement. The most effective approaches combine both participatory and more representative engagement opportunities. Offering opportunities for wider participation mitigates the risk of individuals becoming gatekeepers that inhibit the diversity of views within underrepresented groups from being heard. Rather than relying solely on individuals or small groups to represent diverse groups' interests, opinions, and ambitions, many effective approaches see councils recognising the benefits of people being involved directly and speaking for themselves.

Hopefully long-term having the right people in the room will lead to better decision making.” Participant, West Cheshire Poverty Truth Commission

Partnerships based on equal contribution and shared ambition

The most effective engagement approaches ensured that collaboration is based on the principle that everyone contributes as equals. For those who feel unheard in their interactions with public bodies, engagement with policymakers can feel initially imbalanced and unequal. Focusing on developing a shared purpose and ambition together can be an effective way to establish an equitable and collaborative approach that values the contribution of all those involved. This approach provides a strong foundation, ensuring that relationships are underpinned by sufficient resilience and confidence to withstand 'shocks' and barriers along the way.

The Oxfordshire Homeless Movement (OHM), a partnership between the county, city and district councils, and housing associations, charities, and grassroots groups, seeks to develop a strategic, countywide approach to tackling rough sleeping and the wider issue of homelessness. Oxfordshire Homeless Movement (OHM) aims to help people who are experiencing homelessness or living in supported accommodation.

In response to the pandemic, the government launched the “Everyone In” initiative and advised councils to find accommodation for all rough sleepers regardless of their legal right to support, for example, due to their immigration status. In Oxfordshire, 21 individuals were identified who have no recourse to public funds (NRPF). OHM worked with three delivery partners to provide a housing-led solution for the first six people, with plans to extend the programme to cover the full cohort. As people successfully move on, OHM will refer additional people with NRPF to fill those places, filling the critical gaps in provision that others can’t.

OHM is governed by a steering group, with the voices of lived experience included as a core element within that. The Lived Experience Advisory Forum (LEAF), which is run by and for people with lived experience of homelessness, is co-chaired by a salaried coordinator, funded by OHM.

The co-chairs of LEAF sit on the steering group alongside representatives from non-accommodation-based services, local and national charities, mental health services, the city, district and county councils, Thames Valley Police, a housing association, the University of Oxford, an independent chair and a project manager. The group’s different perspectives contribute to a comprehensive understanding of the challenges of tackling homelessness and work together to provide the insight required to develop a coherent and informed response to tackle homelessness in Oxfordshire.

“The loudest voices we want in that room are people with lived experience of homelessness. We are trying really hard to ensure that the voices that matter the most are at the heart of decision making.”

Research participant, Oxfordshire Homeless Movement

The benefits of securing insight and knowledge on issues and collaboratively developing and delivering shared outcomes are considerable.

Collaboratively developing a vision and purpose can create shared ambition that councils, VCS partners and underrepresented groups can coalesce behind. However, for that vision to gain the support of stakeholders requires strong and persistent leadership, both within the council and local communities. The commitment of leadership teams, elected members and frontline officers can be critical to securing the support and buy-in to ensure meaningful engagement.

Having the right people involved who are in positions to be able to influence change makes a difference. But it’s important not to overlook the support people need to participate meaningfully.

Research participant, West Cheshire Poverty Truth Commission

For councils, this may mean a shift in thinking and practice over what ‘leadership’ means, adopting a more facilitating and enabling role, and being decisive and focused on achieving the desired outcomes.

We see the role of the council as being a coordinator – suggesting and supporting projects, but listening to our partners.

Research participant, Fenland District Council

Key principles to increase civic participation

This research identified a wide range of activities and initiatives undertaken by councils to engage underrepresented communities in civic life. And while the activities varied considerably in terms of their objectives, approaches, and impact, there were common features that transcend the type of authority, geography, or the particular community being engaged.

• strength-based

• collaborative

• honest and open

• adaptable

• proactive and responsive.

Strength-based

Adopting a strength or asset-based approach means recognising the strengths, value and contributions that exist within all communities and, in particular, the benefits of lived experience informing local decision-making.

Traditional approaches tend to focus on engaging with a community when a ‘problem’, in some cases, a lack of civic participation of underrepresented communities is the problem that officials want to fix. However, framing engagement and participation in this way perpetuates the idea that there is something wrong or lacking among those communities and risks overlooking the reasons engagement is low. This is known as a deficit model and can give rise to a self-fulfilling prophecy of inertia, disengagement and embedding divisions.

Instead, participants commented on the importance of explicitly valuing lived experience and seeing it as an asset. This can be achieved by ranking qualitative data alongside quantitative metrics and ensuring lived experience is fed into the evidence base. Softer outcomes arising from ongoing participation of underrepresented groups may be harder to measure. However, they may add significant nuance to hard metrics used to assess outcomes around issues like employment, mental health, and anti-social behaviour.

Successful practices acknowledge the contribution that people with lived experience can make and value their perspective on decision-making and local democracy. Additionally, giving people the opportunity to express themselves can unlock latent community assets and help deliver broader positive local outcomes.

Collaborative

The second principle for increasing participation was working collaboratively with underrepresented groups to shape and deliver plans and activity. This approach includes using co-design and co-production models. The most satisfactory results arose from designing participation models with communities, making decisions together and enacting change collaboratively.

Councils are accustomed to partnership working; however, these are often institutional relationships that operate within corporate parameters, language, and culture. Working with communities requires recognition that working styles may not be compatible and the willingness to address these barriers to collaboration.

One way to overcome these barriers is to work with VCS partners to facilitate relationships between the council and community groups. VCS partners can be a trusted third party, their understanding of community dynamics and council systems and procedures allows them to provide a bridge between seemingly disparate “worlds”. VCS partners can help councils move away from traditional forms of engagement (surveys, focus groups and meetings) to higher levels of engagement like collaboration and co-production requires different approaches. These include having representatives with lived experience on groups and boards, coproducing reports and determining the implications of evidence, collaborative workshops and regular deliberative dialogue.

Adopting these learning and evolving methods is a key step in avoiding some of the less fruitful approaches from the past and can instil a sense of ownership and efficacy.

Honest, open and trustworthy

Increasing civic participation and engagement requires trust, based on meaningful relationships and clear leadership. It is underpinned by transparency of process and honesty about the opportunities, constraints and the ‘red lines’ influencing decisions.

Honesty between parties allowed partners to develop realistic shared aims and build strong relationships based on trust, recognising the mutual benefit achieved by working effectively together. In the strongest examples, we learned of the ‘investment’ made by communities in these partnerships and the expected return, particularly honesty and commitment from the council. While some initiatives are short-lived, achieving sustainable change is a long-term process, with considerable dividends available to those who nurture relationships over time. Such an approach can help avoid ‘consultation fatigue’ or the perception that councils ‘come to ask but not to share’.

Participants reflected on the benefit of hearing ‘authentic voices’ rather than relying on those already engaged. The VCS and trusted advocates can play a valuable role in providing routes to engaging with communities that might otherwise be disaffected. In one such example, there was a perception that the council was the cause of problems, leading to questions about ‘why should we engage?’ Addressing such a significant breakdown of trust is a prerequisite for developing effective and locally sensitive solutions.

Adaptable

It is important to create a range of appropriate, accessible and comfortable opportunities for residents to participate that overcome existing obstacles. This means being creative and willing to adapt as the process evolves. Still further, adaptability is seen in a commitment to explore the ‘journey’; to see that as part of the process will shape the outcome, rather than having a pre-set outcome from the onset.

No single approach will be effective at engaging everyone or appropriate in all circumstances. We’ve heard how deploying a range of methods and approaches increases the opportunities for people to participate in ways that suit them. These needs, preferences and opportunities to engage are not static; they are continually changing. Effective engagement needs to adapt to changing needs and take advantage of new platforms and approaches.

While resources are constrained, budgets can often be found with a degree of creativity and flexibility. As with Global Streets, partnerships can successfully leverage external funds into a local area, enabling activities that might otherwise not exist and access to opportunities that councils could not access in their own right.

Proactive and responsive

In the most compelling examples, positive engagement involves engaging individuals on their own terms and establishing proactive ways to attract participants. This is a significant shift from the ‘broadcast’ or one-directional approach of communicating to a community. Opening up a discussion, inviting input, listening to needs, ambitions, and experiences are central to establishing a genuinely responsive approach.

Proactivity also includes anticipating issues, such as addressing access requirements – for example, ensuring spaces are physically accessible and that neurodiversity is considered. It also requires an appreciation of the pressures on individual lives, such as caring or work responsibilities, and ensuring that contextual factors are taken into account.

A core component of responsiveness is hearing and responding to the views and experiences expressed. Otherwise, frustrations can arise due to the mismatch between expectations and reality, which can fuel cyclical negativity and disengagement.

Community ambassadors can be a useful conduit to more effective engagement. However, they do not represent the definitive view of all people who share similar characteristics. Intersectionality, a term that recognises the multiplicity of the human experience, necessitates a broader view of underrepresented communities acknowledging that while an issue such as poverty might affect large swathes of people, their experiences will have been impacted by a range of other factors such as gender, ethnicity and disability.

Conclusion

Councils across the country are actively seeking new ways to engage groups and communities that have been less visible within local civic life. Successful approaches to this issue are based on common principles that reflect a willingness to find solutions that work equally well for the council, their partners and their communities. The councils' approach and the solutions they have found are as varied as the communities themselves.

There is no single path or process to successfully engaging underrepresented groups in civic participation. We hope the experiences of those mentioned within this report and the evidence we have gathered illustrates the key lessons that can be applied to councils and communities across the country.

Appendix A - Research participants

Our research participants included both council officers involved in engagement initiatives and VCS organisations working with local authorities.

Where an interviewee was from a VCS partner organisation, the council(s) they were working with are illustrated in brackets after the project name.

- Operation Black Vote, Birmingham City Council

- West Cheshire Poverty Truth Commission, Cheshire West and Chester Council

- Leeds Poverty Truth Commission, Leeds City Council

- Gypsy, Traveller and Roma inclusion, Fenland District Council

- Youth Independent Advisory Group, London Borough of Waltham Forest

- Southwark Stands Together, London Borough of Southwark

- Friends, Families and Travellers (London Borough of Bexley, Mid-Sussex, West Sussex and Brighton and Hove Councils)

- Poverty Truth Network (Various, nationwide)

- Oxfordshire Homeless Movement (Oxford City Council, Oxfordshire County Council and District Councils)

- Lived Experience Advisory Forum (Oxford City Council, Oxfordshire County Council and District Councils)

- MiFriendly Cities (Birmingham, Coventry and Wolverhampton City Councils)

- University of Manchester (Greater Manchester)

- Photovoice, Jam and Justice (Greater Manchester)

- Global Streets (Liverpool, Birmingham, Hounslow, Slough, Leicester, Doncaster, Hull, Luton, Barking and Dagenham and Greenwich)