Key points

- This briefing sets out what funding the government has recently announced and how this is being put to good use.

- In November 2022, the Autumn Statement announced new funding for adult social care of up to £2.8 billion in 2023/24 and up to £4.7 billion in 2024/25.

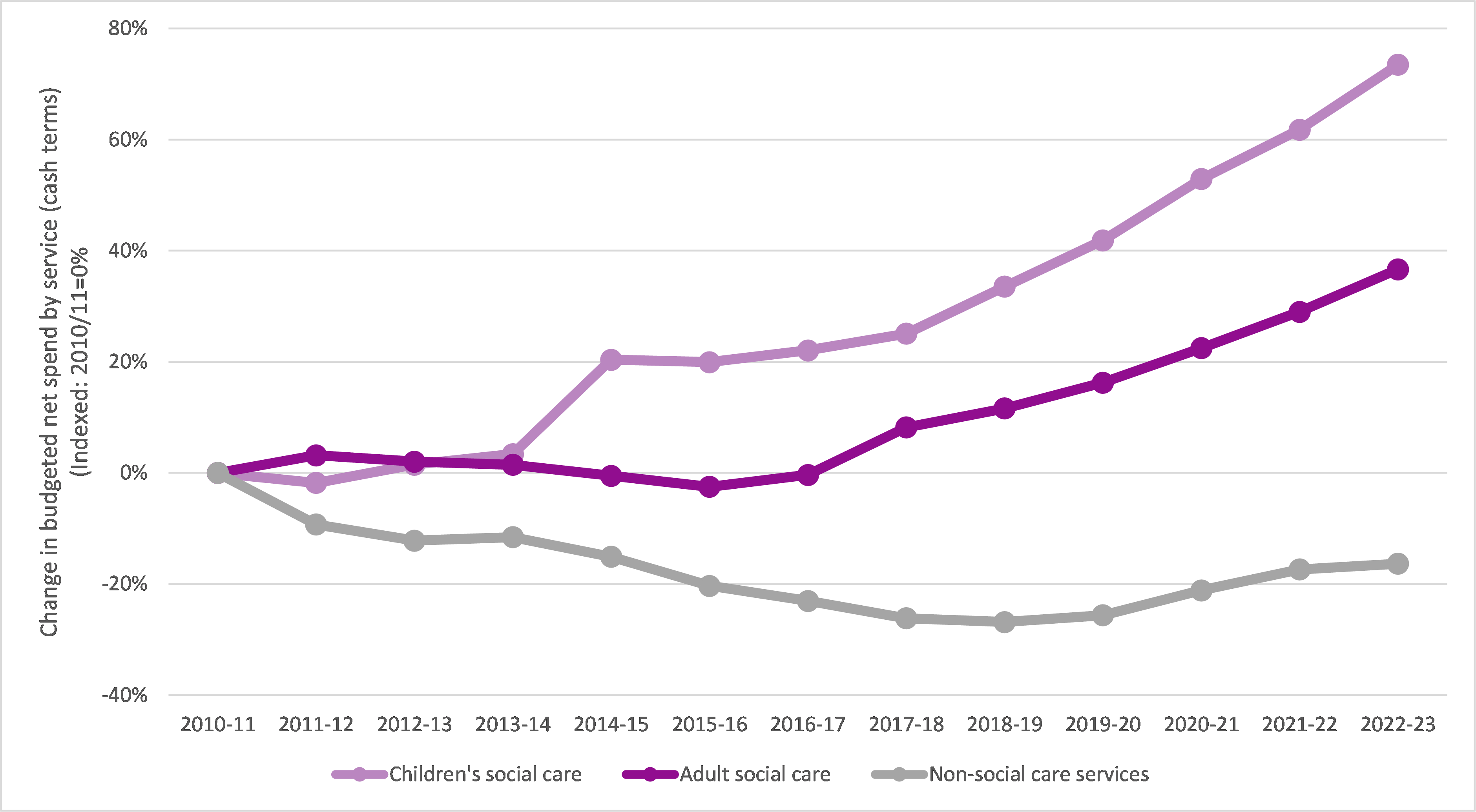

- This funding comes after a decade of falling local authority budgets and what’s been announced remains far short of what’s needed to alleviate pressure on local authorities and the NHS.

- The Local Government Association has called for £13 billion to meet this combination of ongoing pressures and to ensure councils can meet all of their statutory duties under the Care Act.

Overview

This briefing sets out detail and commentary on the funding announced for adult social care in the 2022 Autumn Statement. It does so in the important context of delayed discharge, offering joint LGA and NHS Confederation illustrative thinking on the kind of actions that could be taken to help address immediate pressures in hospitals.

How does new funding compare to councils’ cost and demand pressures?

Councils’ adult social care budgets are a moving target. Patterns of spend do not stand still from year to year. Instead, inflation, wage pressures and demographic changes constantly erode available resources.

Councils seek to address these issues by making annual savings within their overall adult social care budgets. Nonetheless, because of the constant pressure on the core elements of councils’ adult social care budgets, when councils do receive new funding, it is not necessarily all available to support entirely new service provision or to address new forms of demand. Rather, despite councils’ annual savings and efficiencies programmes, in many cases a proportion of new funding is needed to help address the unrelenting demand and cost pressures faced councils’ existing adult social care services.

At the current time, councils face a range of cost and demand pressures, including:

- a 9.7 per cent increase in the National Minimum Living Wage in 2023/24

- a forecast 5.5 per cent increase in CPI inflation in 2023/24, following on from 10.1 per cent in 2022/23

- demographic pressures of £686 million in 2022/23, according to the 2022 ADASS survey.

Given these pressures, and the points above that not all of the announced funding may actually be raised (council tax/precept) or go to adult social care (some will go to children’s social care), it is highly unlikely that that the investment will do anything other than enable adult social care to stand still. It is therefore essential that government and/or systems do not raise expectations unfairly; the funding provided will not all be used to enable significant additional capacity or action on other key issues, such as care worker pay.

These deep-seated issues need to be addressed to put adult social care on a long-term, sustainable footing. Overall, the Local Government Association has called for £13 billion to meet this combination of ongoing pressures and to ensure councils can meet all of their statutory duties under the Care Act. This includes £3 billion towards tackling significant recruitment and retention problems by increasing care worker pay. An investment of this scale is needed to support our national infrastructure, our economy and our prosperity. People who draw on social care and support will remain concerned about the services they access to live the lives they want to lead.

What is the best way to spend the £500 million for maximum impact?

We believe the following kinds of short-term actions could be taken now to help address immediate pressures in hospitals, as well as medium-term actions that will help preparations for next winter. These are illustrative and intended to help shift the focus away from thinking that simply buying more care home beds is the solution to the challenge of delayed discharge.

Short term

- Focus on simple discharge: make sure people without complex needs are discharged rapidly.

- Invest in voluntary sector support: this can mobilise quickly and provide access to an additional workforce. Services such as ‘sitting services’ (which provides reassurance for people who may not need care but are concerned at being alone after discharge), unpaid carer support, handyperson services, and home-from-hospital services can all play a key role in meeting low-level needs after discharge, as well contributing to preventing possible readmission.

- Invest in therapeutic-led reablement: intensive short-term interventions with follow-up support can support recovery after time spent in hospital.

- Increase care worker pay: pay, including one-off increases and/or retention bonuses, can help tackle the serious recruitment and retention issues facing the sector.

- Invest in alternatives to home care, such as:

- one-off discharge personal budgets to buy anything that would aid recovery or could be backfill pay for a family member taking time off

- discharge personal assistants with a small budget to help person settle and/or arrange longer-term support

- bursary to attract 18-25 year olds to care work

- ‘telecare in a bag’ kit (this is the issuing of care technology to people directly from hospital. This might be, for example, a handset with an emergency button which can be linked to an emergency monitoring centre. This solution ensures that people can get home quickly but with support in place should it be needed).

Medium-term

- Focus on prevention and recovery services, including steps to support the voluntary sector to provide fast, low-level support is essential.

- Build on the good work being done in some areas to identify and target the people most at risk of admission.

- Invest properly in primary and community services.

- Tackle the long-standing issue of care worker pay.

What are some examples of innovation and best practice on delayed discharge?

National Discharge Frontrunner sites: Humber and North Yorkshire Health and Care Partnership

In June 2022, NHS England sought expressions of interest from local systems to lead the way in developing and testing radical new approaches to discharging people from acute care. After a competitive selection process, over a number of months, Humber and North Yorkshire Health and Care Partnership has now been selected as one of six sites selected nationally as a Discharge Frontrunner.

The main objective of the Humber and North Yorkshire programme is to ensure more people are supported to leave acute care and have the right support, in the right place, in a safe and timely manner. Technology is at the heart of this to enable a ‘single version of the truth’ – this will highlight any delayed discharge, who owns the delay, and provide alternative pathway capacity to help expedite to alternative community provision.

The technology being implemented is an application built in collaboration between NHS, social care and voluntary, community and social enterprise organisations. This is called Community OPTICA and tracks the total community capacity across the health and care system for the purpose of admission avoidance and timely discharge.

The successful Discharge Frontrunner sites were announced in January 2023, and the Humber and North Yorkshire scheme will now begin implementation using a phased programme over the coming months, looking to integrate further partners as it does so. The scheme will run for 12 months as a pilot, but it is hoped that this can be extended beyond the initial period and replicated across the country.

About Humber and North Yorkshire Health and Care Partnership

Humber and North Yorkshire Health and Care Partnership is one of 42 integrated care systems (ICSs) which cover England to meet health and care needs across an area, coordinate services and plan in a way that improves population health and reduces inequalities between different groups. The partnership comprises of NHS organisations, local councils, health and care providers and voluntary, community and social enterprise (VCSE) organisations.

Working across a large geographical area, Humber and North Yorkshire includes a population of 1.7 million people and incorporates the cities of Hull and York and the large rural areas across East Yorkshire, North Yorkshire and Northern Lincolnshire.

Intensive implementation of D2A Home First: North Cumbria

Background

The Local Government Association (LGA) was approached in June 2020 by North Cumbria to carry out a peer review. Cumbria had received several interventions over recent years to help address performance issues in relation to flow, particularly hospital discharge. While some improvements were achieved in the short term, these had not been sustained. Through the Better Care Support Team (BCFT) bespoke support programme run by the LGA, a team of peers was convened to act as a critical friend and support improvement.

Making the change happen

- Recognised that we needed support to break the cycle and make change happen

- LGA/ECIST Executive Enquiry – short, focussed; quickly identified strengths, opportunities for improvement, and an action plan

- Brought Systems Executives together weekly in focussed way – forged strong System

- Leadership (regular input from LGA/ECIST)

- Fortnightly Health and Social Care Group – led by LGA/ECIST colleagues - sharing learning, building relationships breaking down historical barriers and narratives in a safe space (shared understanding and effective leadership at all levels)

- Recruitment of Home First System Co-ordinator – impact of this post, holding all parts of the system to account has been really powerful. We do not think we would be where we are now, where it not for this role in terms of challenge, holding the mirror up and delivering change at pace.

Tools to support change

- Welcomed the challenge into the system – the push back against the blame culture – and realisation that delays in the system were not down to one partner

- Ongoing support, knowledge, experience and networking opportunities that working with the LGA and ECIST has brought has been invaluable

- Dedicated workshops to help understand and better define offer and impact for 7 day Transfer of Care Hub

- Commissioning, Home First Models, Assistive Technology – learning from others, together

- Flexibility of in-house Provider & relationships with independent sector.

Outcome

- Improved flow through hospitals

- Huge reduction long length of stays

- Improved ambulance handovers

- Improved discharge experience for patients and providers

- Streamlined effective information gathering prior to discharge and agreed with providers

- Improved daily reporting that informs areas for focussed attention

- Improved morale and motivation

- Co-production and the opportunity to influence change

- Greater understanding of each other’s roles, responsibilities and realities

- Celebrating as a system is really powerful and shared ownership of the risks and challenges that we face everyday.

Hospital Discharge: Stockton-on-Tees Borough Council

‘I don’t have many friends and family, the help the staff gave me put my mind at ease, I’m not sure what I would have done without them. I was very worried about how I would manage at home after being unwell, but the support was there the same day I got home and was very good.’

This is George’s experience of the partnership between Stockton-on-Tees Borough Council, North East and North Cumbria Integrated Care Board (ICB) and North Tees and Hartlepool NHS Foundation Trust which operates a collaborative, integrated and embedded model of care for hospital discharge. Organisational commitment and the positive relationships between staff from each organisation have resulted in the creation of joint strategic planning and joint operational decision making that focuses on achieving good outcomes for people leaving hospital.

Professional opinions across health and social care are equally valued and forward planning and early, effective communication are key to the hospital discharge model. Daily multi-disciplinary huddles and weekly strategic planning meetings take place to ensure there is a ‘no surprises’ approach. Hospital discharge services can be time sensitive, and this can lead to a high-pressured environment, however these challenges have been overcome with effective continuous communication and engagement enabling multiple professionals from a variety of organisations to pull together for the same goal, providing personalised support to people.

A critical element of the model is forward planning with commissioning, finance, and procurement teams. Intelligence collated by partners is used to develop and support the delivery of appropriate responsive and flexible services with our independent care provider market.

The local system wrapped around North Tees and Hartlepool NHS Foundation Trust is enabling timely and effective hospital discharge, supporting people to move to an environment they can thrive in. The performance indicators of criteria to reside and length of hospital stay (7+, 14+ and 21+ days in hospital) all show that the local system performs as one of the best across all indicators.

What should we learn from this ahead of next winter?

Local council and healthcare leaders welcome the additional discharge funding on top of the Adult Social Care Discharge Fund the government announced last September. However, the last-minute and short-term nature of the funding does not match the more fundamental challenges the health and care sector is facing – the widening gap between the capacity, resource and need.

In addition, short term, prescriptive funding pots limit the ability of the sector to innovate, creating more risk that we invest into extending existing services rather than reimagining more joined-up care that makes best use of staff available.

Discharging more patients from hospital into care homes will help flow and is a better alternative than medically fit patients being prevented from leaving hospital. However, it also runs the risk of people being inappropriately placed and remaining in residential provision indefinitely. The risk of this is heightened by needing to make rapid decisions around care and arrange full wrap-around support required for people to make full recoveries. The implementation of the interventions is further hampered by the substantial reporting burden attached to the funding – the specificity of criteria and volume is significantly constraining flexibility and adding bureaucratic pressure.

Next winter, the government must set out its plan for winter well in advance of the season, so that systems can design and deliver solutions that are appropriate to the local challenges they face.

These will be more sustainable, make the best use of limited resource and work towards the best outcomes for all patients. This includes the government setting out and sticking to a clear timetable for when funding reaches the frontline, allowing flexibility in how it is spent, and reviewing the reporting requirements. This must also provide clarity around future funding availability so interventions can become lasting solutions.

Strengthening community capacity in both health and social care is the answer but this takes investment and time. Unless record low staffing levels and low pay are addressed it will be nothing more than a winter quick fix, and the same problems will return.