Introduction

This ‘Must Know’ outlines major changes to health and care integration arising from the Health and Care Act. Subject to the Bill’s passage through Parliament, integrated care systems (ICSs), which have been operating as voluntary partnerships, will be placed on a statutory footing in April 2022. Each ICS will have an integrated care board responsible for NHS and wider integration, and an integrated care partnership responsible for promoting health, care and wellbeing. Each ICS will also comprise partnerships at place level and joint arrangements at locality level through primary care networks.

This Must Know considers interim guidance as available in Autumn 2021 and sets out key messages for developing arrangements that will drive key aims of integration:

- improving outcomes for people who use health and care services, carers and communities

- improving their experience of services

- developing prevention to promote health, wellbeing and independence, and tackle health inequalities so the demand for statutory, intensive or long-term services will be reduced.

This Must Know includes examples of health and care systems that have focused on developing strong partnerships both across the system at ICS level and in place-based partnerships.

For more detailed information on the shift to preventative support see the Local Government Association (LGA) Must Know on Prevention.

This Must Know updates the 2020 Must Know on integration and will be updated again in 2022 to reflect the final legislation and statutory national guidance, as well as the implications of the forthcoming integration White Paper, which is due in 2021. It will also explore how new arrangements can drive further improvements in integrating health and care.

Key messages

Ensure that integration maintains a focus on outcomes – integration is not an end in itself; it is a means to better health and care support, better health and care outcomes and better use of resources.

Proactively shape the new ICS governance structures so that health and care integration, shifting resources to prevention and community services, and tackling health inequalities will be top priorities.

Where there is more than one council with social care responsibilities in the ICS, ensure there is effective collaboration between councils and between health and wellbeing boards.

Integrated care boards – where there is more than one council in the ICS, it may be helpful to propose more than one local government board member to provide a wider range of knowledge and perspectives. The local government member or members should establish effective two-way communication with health and care leaders in all councils and with health and wellbeing boards.

Integrated care partnerships – work with the NHS and wider partners so integrated care partnerships operate effectively across the system and its places and neighbourhoods. Consider how integrated care partnerships and health and wellbeing boards will work together. Where there is more than one health and wellbeing board in the system, ensure that the integrated care partnership involves appropriate representation from each of these, and that effective collaboration is in place.

Place-based partnerships – work with health and other colleagues to build-on existing effective place-based partnerships, such as health and wellbeing boards, to ensure that decision-making over delivery and resources happens in places that make sense to people and as close as possible to communities.

Health and wellbeing boards should collaborate so that joint strategic needs assessments and joint health and wellbeing strategies can shape the integrated care strategy. Ensure that the voices of people who use services and carers, local communities, and the voluntary and community sector, are included in the integrated care partnership and its strategy.

Make sure that any effective existing integrated health and care initiatives in place-based partnerships are not lost in system-wide reconfiguration.

Consider using the good practice tools and frameworks in the resources section of the must know to help shape partnership arrangements.

What you need to know

How integration has developed

Integrating health and social care to provide joined-up support that delivers better health and wellbeing outcomes to individuals is a long-standing national and local policy objective. Councils and NHS partners have been delivering integrated services, undertaking joint commissioning, and pooling funding for many years. In recent years, it has been national and local policy to escalate the scale and pace of integration.

Integrating health and social care is one element of a wider integration agenda which includes integration across the NHS – the ‘triple integration’ between hospitals and primary care; the NHS and social care; and physical and mental health. NHS reforms have developed a new landscape for health planning and delivery framed around large geographical footprints; first, sustainability and transformation partnerships, then integrated care systems, which developed into the levels familiar today:

- integrated care systems

- places – often equivalent to a shared clinical commissioning group (CCG) and local authority area, or part of the footprint for a large council

- primary care networks – partnerships between GP practices which aim to involve community health and care services – generally around 30,000 to 50,000 people

- neighbourhoods and communities – smaller areas where people may have specific health and care needs.

The 2019 NHS Long Term Plan built on previous strategies to promote integration, prevention and reduce health inequalities, but NHS England and NHS Improvement (NHSEI) concluded that the full potential of integrated health and care could not be achieved through voluntary partnerships. The Government asked NHSEI to identify legislative barriers and, following consultation, the health and care White Paper Integration and Innovation, was published in February 2021. Some key asks from local government, such as the importance of place in planning and delivering integrated health and care and the need for local government and wider stakeholder involvement in ICSs, were included in the White Paper. The Health and Care Bill was published in August 2021 and is expected to become law, with a tight timescale for implementation, in April 2022.

An integration White Paper, expected by the end of the year, is likely to announce further moves to escalate the scale and pace of integration.

The Health and Care Bill − integrated care systems

The Health and Care Bill has wide-ranging provisions, many of which concern how NHS organisations work more effectively together. This Must Know is focused on the role of ICSs as a central core of the reform agenda.

ICSs are the overall partnership of health and care organisations that plan and deliver joined-up services to improve the health and wellbeing of people in their area. Their four overarching aims are to:

- improve outcomes in population health and healthcare

- tackle inequalities in outcomes, experience and access

- enhance productivity and value for money

- help the NHS support broader social and economic development.

ICSs will have two statutory components: integrated care boards (ICBs) and integrated care partnerships (ICPs).

ICBs are statutory bodies which bring NHS organisations and ‘partner members’ together to improve population health and care. Subject to the passage of the Health and Care Bill through Parliament, they will take over commissioning GP services from CCGs in April 2022 when CCGs will be disbanded. Some will also take on dental, ophthalmic and pharmaceutical commissioning then, with all doing so by April 2023. NHSEI interim guidance says that their functions include allocating resources, financial accountability, establishing joint working arrangements with partners, and leading system-wide action on workforce, digital and data capabilities, estates and procurement.

ICBs will be able to delegate functions and budgets to place-based partnerships and to provider collaboratives while maintaining overall accountability for NHS resources.

Explanatory notes to the Bill indicate that ICPs are statutory joint committees to be established by the ICB and local authorities in the system as equal partners. ICPs bring together, as a minimum, partners from health, social care, public health, the voluntary and community sectors, and the views of people who use health and care services and communities. The ICP will develop an integrated care strategy to address the health, social care and wellbeing needs of the local population. The ICB and local authorities in the system must have regard to the integrated care strategy when making decisions.

Statutory guidance on the Bill cannot be issued until it is passed by Parliament, but some interim guidance has been published by the Government, NHSEI and the LGA. A comprehensive suite of guidance and good practice will follow. The guidance provides a framework for implementation. There are some requirements, particularly on ICBs as statutory bodies, but overall, there is considerable potential to build on current partnerships that are working effectively to establish arrangements and governance structures that best fit the system and its places.

The wider context: social care reform

Build Back Better, the government’s plan for health and care, sets out a number of initiatives intended to improve the NHS and social care. These include a cap on maximum care costs, an increase in financial means-test thresholds before people are required to pay for care and a levy on National Insurance contributions with the funding to be invested in health and care. The plan also announced that the Government will work with stakeholders to publish a White Paper for reforming adult social care.

Overall, the plan is light on detail and does not resolve the funding deficit. Adult social care has been in urgent need of reform and a fair funding settlement for many years. Over the past decade, councils have had to meet a £6.1 billion social care funding gap through savings and diverting money. Of the estimated £36 billion the new UK-wide health and social levy will raise over three years, only £5.4 billion is to be ringfenced for social care. Unlike for the NHS, none of this funding appears to be allocated to help tackle the large, immediate pressures facing social care; also, funding the cap on care costs and increased financial means test thresholds will absorb a substantial part of this. National NHS member organisations and prominent think tanks agree that funding reform for adult social care is urgently needed to progress integration and to address the negative impact of social care budget constraints on NHS services.

What you need to do

Moving to statutory commissioning organisations and ensuring that healthcare services continue to operate safely and effectively is a complex task, particularly for ICSs that cover several CCGs. As well as the need to land services safely by April 2022, organisational restructuring involves resolving complex human resource issues. The fact that the legislation is not yet in place to formally allow these moves is an added pressure for the NHS. Establishing ICBs and ICPs and the constitutional issues involved in new governance will also take time and focus.

In recent years, some ICSs have forged ahead, creating strong partnerships across the NHS and local government. They have developed integrated health and care services and preventative approaches at scale, while maintaining a focus on planning and delivery at the level of place and starting to realise the potential of community-based activity linked with primary care networks. While there is still much more to be done, inclusive ICSs demonstrate what can be achieved in a relatively short period of time: see examples.

There is a widespread consensus that the COVID-19 pandemic has improved joint working across the NHS, councils and other partners and has shown how effective place-based partnerships are at responding to the needs of their communities. Swift decision-making, a can-do attitude and mobilising resources quickly have strengthened both strategic and front-line partnerships. There is also a strong commitment to nurture and extend these positive changes.

At a time of organisational change, the focus in the coming months is to work with partners to shape ICS arrangements so that they offer an effective basis for action for the key elements of integration:

- improving health and care outcomes for people who use health and care services, carers and communities

- improving their experience of health and care services

- developing prevention to promote health, wellbeing and independence, and tackle health and wider inequalities so the demand for statutory, intensive or long-term services will be reduced.

Guidance in more detail

This section summarises elements of interim guidance, available at the time of writing, that relate to the role of government and to wider partnerships. It also identifies issues for local government to consider when contributing to developing ICS structures.

Integrated care boards

NHSEI’s interim guidance on the functions and governance of ICBs says that, before April 2022, ICSs must have recruited members to the board, engaged with partners to develop a constitution and submitted this to NHSEI, and developed a ‘functions and decisions map’ showing arrangements within the ICB and with ICS partners to support good governance and effective decision-making.

ICBs will lead NHS integration and will also work on integration and population health, beyond the NHS, with local government and other partners. Their agenda covers issues at the interface of health and care integration, such as personal care, personal health budgets and direct payments, collaboration on workforce and digital, and wider areas such as health inequalities, social and economic development, and environmental sustainability.

The ICB must have at least one local government member drawn from the council or councils in the ICS with social care responsibilities, expected to ‘often be’ the chief executive or other relevant executive-level role. ‘Partner members’ will bring ‘knowledge and a perspective from their sectors, but not acting as delegates of those sectors’. They will be nominated jointly by their sector based on skills and experience through a selection process – more guidance will be issued on this.

ICBs must develop a plan to meet the health and healthcare needs of the population in their area, which will have regard to the integrated care strategy.

Integrated care partnerships

Councils with social care responsibilities in the ICS and the ICB chair and board have equal responsibility for establishing ICPs. The DHSC’s ICP engagement document, which was co-produced with NHSEI and the LGA, says that ICPs cannot be formally established until the designated ICB chair and chief executive and possibly the wider board are in place. In this case, the Government expects at least an interim ICP comprising a chair and representatives from the ICB and relevant local authorities, and agreement over resourcing the ICP.

There are some requirements on how ICPs should be formed, and some expectations for good practice – set out below – but beyond this, partners have flexibility to establish arrangements that best meet system and local needs.

Councils and the ICB will need to agree how the ICP will be resourced, including any remuneration for the chair. The role of the ICP chair is vital. The guidance identifies the following characteristics: ability to build and foster strong relationships; collaborative leadership style; commitment to innovation and transformation; expertise in delivery of health and care outcomes; and ability to influence and drive delivery and change.

On membership, Annex C of the engagement document indicates that the ICP should have a broad membership and engagement with communities, but membership should ‘be managed appropriately to ensure that the operations of the ICP remain efficient and effective’. Healthwatch has an important role, and ICPs are expected to go further in involving people, and to develop proposals for engagement. Annex C suggests some of the groups and individuals who should have representation on the board or be engaged in its work.

In ICSs with one council, the health and wellbeing board (HWB) cannot act as an ICP, but alignment should take place to ensure joined-up decision making, common membership can be agreed, and arrangements can be streamlined. Larger systems should consider single or multiple representation from HWBs.

ICPs are responsible for producing integrated care strategies that take account of existing joint health and wellbeing strategies and joint strategic needs assessments (JSNAs) in the system. They should work on cross-cutting issues that cannot be solved by one organisation or one place alone. There is an expectation that ICBs should share relevant data to allow timely decision making.

ICPs should promote integrated working from place to system levels, drawing on partners’ experiences of challenges in improving health and care outcomes and tackling social determinants of health such as poverty, worklessness and the impact of climate change. They should champion inclusion and transparency in places and neighbourhoods to ensure the system is connected to communities.

Place-based partnerships

Place-based partnerships involve local organisations responsible for planning, arranging and delivering health and care services. In many areas these involve shared leadership, joint commissioning and integrated service delivery. Many also have a role in promoting health and wellbeing and tackling health inequalities.

NHSEI and LGA interim guidance on place-based partnerships – Thriving places – says existing arrangements that are working well should be built upon. The guidance is intended to help partner organisations in ICSs to collectively define and agree their place-based partnerships, using principles such as ‘subsidiarity’ and ‘form follows function’ to:

- define place within the health and care system

- define the purpose and role of place-based partnerships

- establish leadership, governance, decision-making and accountability.

Place-based partnerships are described as the foundations of ICSs. They are seen as playing a ‘central role’ in planning and improving health and care services as well as working with others to tackle health inequalities and influence the social determinants of health. The guidance identifies several potential models for place-based partnerships.

NHSEI interim guidance on ICBs states that discussions with partners and decisions on commissioning arrangements at the level of place should be finalised by the end of quarter 3.

How the ICB and ICP work together

The ICB will need to align its constitution and governance with the ICP. It is expected to consider how joint working with partners at all levels will support progress in reducing inequalities and improving outcomes. The ICB plan must support the integrated care strategy and ensure strategic alignment with agreed, values, goals, objectives, initiatives and cross cutting issues. The ICB must share intelligence, so health and wellbeing needs are widely understood and opportunities for at-scale collaboration are maximised. It must set out how ICPs can be assured about delivery.

ICPs and ICBs should develop formal agreements for engaging with and embedding the voluntary, community and social enterprise sector. They need to support clinical and care professional involvement in the development and delivery of the integrated care strategy.

Areas of focus

Establishing the new arrangements

The Health and Social Care Bill is intentionally light touch to allow partners maximum flexibility in developing partnerships and governance. All the guidance is clear that where existing partnerships are working effectively, new arrangements should build on positive ways of working.

ICBs can appoint additional local government members to the board. Dependent on the configuration of the ICS, it may be helpful to propose more than one local government member to allow a wider range of perspectives and knowledge.

ICP membership should include a range of perspectives, including essential voices from people who use services, communities, and the voluntary and community sector. They must also be of a size to enable clear decision making, so clear arrangements are needed for involving all stakeholders, including partners with a role in the social determinants of health. The ICP needs representation from every HWB within the ICS.

ICPs and ICBs need a wide perspective and understanding that span the system, places, and neighbourhoods. The roles of the local government member or members on the ICB and that of constituent HWBs within the ICS are crucial for this.

- In multi-council ICSs, arrangements for time-limited tenure for the local government member or members on the ICB could be considered. The member/members will need a good understanding of the needs and priorities of each place, as well as their aspirations for system-wide developments at scale; formal communication should be established to support this.

- ICPs need strong links with any constituent HWBs. Members of the ICP will need to understand the distinct population needs and priorities of all HWBs in a system, expressed through JSNAs and health and wellbeing strategies in order to develop the system-wide integrated care strategy. Some HWBs have already established effective joint working; HWBs without strong working links will need to accelerate collaboration.

Place-based partnerships are seen as the foundation of ICSs. There are a range of potential models for place-based arrangements, but those that formally delegate decision-making and budgets from ICSs to places mean that decisions will remain close to communities and in places that make sense to local people after the disbanding of CCGs.

Any existing effective integrated health and care and prevention initiatives in place-based partnerships should be supported to continue and not be lost in system-wide reconfiguration.

Focus on improvements

April 2022 is an important milestone in establishing governance and partnership arrangements within ICSs, but it is not the end point for development.

The relationship between the ICB and the ICP is fundamental to successful health and care integration. They need to interact effectively so that the overall vision and priorities for health, care and wellbeing set out in the integrated care strategy are owned and implemented through all levels of the system by the NHS, local authorities and other partners.

When health systems were introduced, many areas undertook organisational and cultural development to understand the cultures and requirements of different sectors. This often took place at all levels of organisations, from senior leaders to front-line staff and led to shared visions, values and principles for working together. New system and place arrangements are likely to benefit from such an approach.

Some areas have already made progress on using the principle of subsidiarity to determine what activity works well at scale and what is best carried out in places and with neighbourhoods. Some have worked with partners in other areas to align JSNAs and share ideas and resources such as population health observatories. The LGA’s What a difference a place makes describes 22 effective, outward-looking HWBs. But even the most collaborative local partnerships will need to work on aligning JSNAs and joint health and wellbeing strategies so that local needs and priorities feed into the ICP’s integrated care strategy in the most effective way.

The work of ICPs, and forthcoming integrated care strategies, need to be balanced so that all of the following areas are included, with specific priorities identified according to system-wide and local needs:

- improving integrated health and care leading to improved health and care outcomes and a better experience of services for individuals, and the most efficient use of resources by organisations

- shifting resources from acute, crisis and long-term health and care provision to preventative initiatives across all three levels of prevention

- tackling health inequalities and involving wider partners in addressing the social determinants of health.

Place-based partnerships should have a population health role which includes developing local preventative approaches and tackling the wider determinants of health. They should also involve primary care networks and communities to develop asset-based neighbourhood support. More information is available in this report: Achieving integrated care through community and neighbourhood working: A high impact change model

Resources for good practice in shaping integrated health and care

This section identifies resources to support the development of integrated health and care in systems and places.

Vision, principles and key actions

The LGA has worked with partners to develop a vision and principles for developing integrated health and care. The partners are the Association of Directors of Adult Social Services (Adass), the Association of Directors of Public Health (ADPH), NHS Confederation, NHS Clinical Commissioners and NHS Providers. The principles have been well received by health and care leaders who find them helpful in testing partnership arrangements, visions and plans. The principles are:

- collaborative leadership

- subsidiarity – decision making as close to communities as possible

- building on existing successful local arrangements

- a person-centred and co-productive approach

- a preventative, asset-based and population health management approach

- achieving best value.

The 15 best practice actions for effective integrated care were developed by the LGA and the Social Care Institute for Excellence (SCIE) for planning integrated care in systems and places. They provide a more detailed checklist for keeping partnership arrangements on track.

| Realising person-centred coordinated care | Building place-based care and support systems | Leading for integration |

|---|---|---|

|

1. Risk stratification Identify the people in your area that are most likely to benefit from integrated care and proactive support and preventative support. |

6. Operational framework Create an integrated care operational framework that is right for the local area and which aligns service delivery and service changes to a clear set of benefits for local people. |

11. Common purpose Agree a common purpose and a shared vision for integration, including setting clear goals and outcomes. |

|

2. Access to information Ensure individuals and their carers have easy and ready access to information about local services and community assets. Also, that they are supported to navigate these options and to make informed decisions about their care. |

7. Integrated commissioning Use integrated commissioning to enable ready access to joined-up health and social care resources and transform care. |

12. Collaborative culture Foster a collaborative culture across health, social care and wider partners. |

|

3. Multidisciplinary team training Invest in the development and joint training of multidisciplinary teams (MDTs) to transform their skills, cultures and ways of working. |

8. Shared records Identify and tackle barriers to sharing digital care records to ensure providers and practitioners have ready access to the information they need. |

13. Resource allocation Maintain a cross-sector agreement about the resources available for delivery the model of care, including community assets. |

|

4. Personalised care plans Develop personalised care plans together with the people using services, their family and carers. |

9. Community capacity Build capacity for integrated community-based health, social care and mental health services, focusing on care closer to home. |

14. Accountability Provide a system governance and assure system accountability. |

|

5. Rapid response Provide access to integrated rapid response services for urgent health and social care needs through a single point. |

10. Partnership with voluntary, community and social enterprise sector Foster partnerships to develop community assets to provide easy access to a wide range of support. |

15. Workforce planning Lead system-wide workforce planning to support delivery of integrated care. |

Figure 1 - Achieving integrated care: 15 best practice actions

Care and Health Improvement Programme

The LGA’s Care and Health Improvement Programme provides a wide range of free peer-led support for health and care systems, including peer reviews, workshops and on-site bespoke support. This includes a System Transformation Peer Support programme delivered jointly with NHS Providers and NHS Confederation. This focuses on strengthening system leadership and partnerships through developing local ICS, place-based partnership and HWB arrangements. Other programmes offer support around HWBs, community care models, and hospital discharge and intermediate care as well as on supporting the care market and health and care workforce. More information can be found on the LGA website or email [email protected]

SCIE resources

SCIE provides a range of resources – guides, webinar recordings and practical tools – that provide additional support on the key actions for integrated health and care. Topics include:

- the key elements of integration – transfers of care, intermediate care, prevention strategy and end of life care

- working with individuals and communities – asset-based places, person-centred care, self-care, co-production and advocacy

- enablers – leadership, workforce, partnership working, finance and budgets, measuring impact

- innovation in small scale models of integrated health care and support for adults

- transforming care and support for better care outcomes.

Localised decision making

The LGA and NHS Clinical Commissioners have produced a guide to localised decision making which uses the principle of subsidiarity to describe how decision making can be taken at the most appropriate level. The guide provides a checklist for identifying decision and resource allocation processes, close to communities, at the level of place.

The Kings Fund has reviewed existing evidence and experience of place-based partnerships, confirming their role as the ‘foundation of effective integrated care systems’. Their report identifies key success factors and sets out principles to guide local health and care leaders in developing arrangements.

Learning from people and communities

The Kings Fund has published a guide to putting people and communities at the heart of how integrated care works and develops. It offers a practical, evidence-based approach to help partners in systems, places and neighbourhoods to work with communities to identify what people need, what is working well and what more needs to be done to provide joined-up care.

Questions to consider

- Subject to guidance, are arrangements being made to select a local authority member, or members, on the ICB? In areas with more than one local authority, are arrangements for effective communication and engagement being established?

- Will the form of the ICP support clear decision-making, while also taking an inclusive approach to engaging with the widest range of stakeholders?

- What organisational and cultural development work is taking place, or planned, to support establishing the ICB and the ICP as inclusive, collaborative and effective forums?

- Have effective links between the emerging ICP and any HWBs been established to ensure that the integrated care strategy will build on joint strategic needs assessments and joint health and wellbeing strategies?

- What arrangements are in place to ensure effective collaboration between HWBs where there is more than one in the system?

- Will place-based partnerships build on what is already working well and involve decision-making on delivery, resource allocation and planning?

- Will the relationship between place-based partnerships and HWBs enable them to work together fulfil their roles in improving health and care, increasing prevention and tackling health inequalities?

Examples of integrated health and care

Coventry and Warwickshire Place Forum

Coventry and Warwickshire ICS covers a population of around 943,000 people across two local councils. The two HWBs in Coventry and Warwickshire formed a single Place Forum to work with the new health and care system (now Coventry and Warwickshire ICS) to promote health and wellbeing, tackle health inequalities and promote integrated health and care. The forum has a key role in ensuring that all partners are involved in shaping how the ICS develops. Measures include:

- the forum developing an alliance concordat setting out how partners will collaborate in a place-based population health approach

- the forum and the ICS Health and Care Partnership Board holding joint meetings which develops a shared understanding of both priorities affecting the NHS and the potential of partnerships for addressing social determinants of health

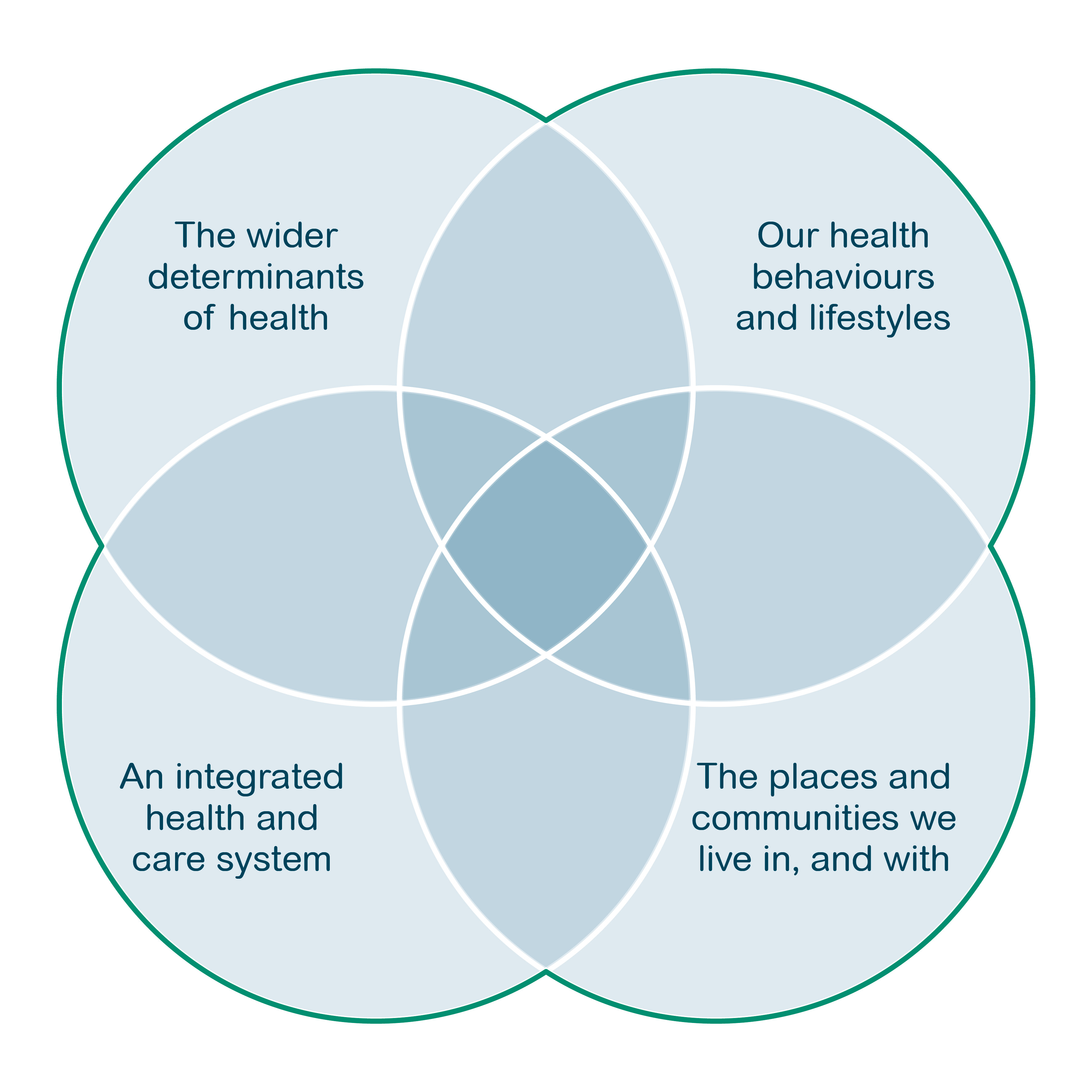

- the Place Forum, the ICS and the individual HWBs adopting the Kings Fund quadrant population health model as a shared framework for their prioritisation and work programmes.

As ICSs move towards statutory status, future working arrangements are seen as evolving from the shared direction already established and there is a firm commitment to ensuring that the new arrangements capture the strong history of collaboration across Coventry and Warwickshire around the wider health and wellbeing agenda. There is a strong focus on planning and delivery at the level of place, with a guiding principle that around 80 per cent will relate to places, 20 per cent at scale across the ICS.

The ICS has four well-established place-based planning and delivery partnerships involving health commissioners, adult social care, NHS providers and the voluntary and community sector; one in Coventry, three in Warwickshire, each with a health and wellbeing partnership board and an executive board. Place-based arrangements and collaboratives will evolve to meet the new statutory requirements of the ICS and will include devolving budgets and decision-making to the appropriate level.

The individual HWBs have had support from the Kings Fund to explore their role and contribution as place-based leaders for health and wellbeing and how this will feed into new statutory arrangements. A combined workshop with the HWBs, the Place Forum and ICS Partnership Board will help to shape how partners will work together in the new arrangements, such as the new ICP.

Place Forum impact

In 2019 the forum delivered a ‘Year of Wellbeing’ in which partners worked together to showcase practical benefits of prevention and self-care. Work is now underway to cement the legacy of the year, with a particular interest in exploring the potential role of anchor institutions. Developments include:

- Wellbeing for Life aims to raise the profile of local prevention opportunities and encourage people to be proactive about their own health and wellbeing across Coventry and Warwickshire, working with local communities, schools and workplaces.

- The Call to Action on inequalities asks all businesses and organisations across Coventry and Warwickshire to consider how they can help to address health inequalities through their working practices. Call to Action provides examples of how businesses could help to reduce inequalities and seeks pledges to take action. Both areas are delivering initiatives to tackle health inequalities in the workplace.

The system was quick to recognise the potential of the COVID-19 pandemic to exacerbate existing deep-rooted inequalities. A joint rapid COVID health impact assessment allowed it to understand the impact on communities and to mobilise action. The impact assessment validated the population health model and led to an immediate focus on deprivation and black and minority ethnic communities. Action taken by partners includes support for economic recovery, wellbeing support for frontline staff, addressing impact on mental wellbeing and social isolation, and reviewing support for rough sleepers.

West Yorkshire and Harrogate ICS

West Yorkshire and Harrogate (WY&H) ICS covers a population of around 2.7 million people across six areas: Bradford District and Craven, Calderdale, Harrogate, Kirklees, Leeds, and Wakefield. The ICS was established with the principle that place has primacy, that the ICS is the servant of place. Based on this, partnership arrangements have been co-produced over several years, building on the strengths, capacity, and knowledge of all partners, and working with communities.

Integrated care partnerships were established in each of the places, bringing together key partners across health and social care, including primary care networks; social care; the voluntary, community and social enterprise sector; mental health, learning disabilities and autism services; acute provider collaboratives; and integrated commissioning. Each partnership identifies common needs and aspirations and undertakes population-based planning and improvements to service delivery with an ethos of partnership between commissioners and providers.

Partnerships are supported to develop their potential by the Integrated Care Partnership Development Framework. The framework is based on shared learning and examples of local good practice from across the ICS with the aim of developing a culture of collaboration, continuous improvement and smoother transition – embodying principles like ‘people own what they create’. It involves a series of statements for places to assess progress on measures such as: vision, health and care needs assessment, leadership, community involvement, place-based plans, review and evaluation, and enablers. It promotes a level of consistency across the ICS while recognising that each partnership operates in a unique local environment.

The framework provides the basis for a mutual accountability framework within the future ICS governance arrangements, including the mechanisms for place-based financial allocations, decision-making, risk management and governance. The ICS sees the change to statutory arrangements as endorsing the direction that was already underway in WY&H – a clear ICS operating model coproduced by partner organisations and effective collaboration at local level. The framework will continue to evolve and support places as they embed new changes. For example, within integrated place partnerships there is a focus on smaller neighbourhoods where local health and care providers come together to serve local communities and tackle health inequalities.

From an early stage, place-based leaders have taken responsibility for ICS-wide priority programmes of work to ensure these are grounded in place while benefitting everyone living across the area. The ICS publicises the impact and value for money of priority programmes on its website. System working has led to positive change in hyper acute stoke units, vascular services, assessment and treatment units for people with complex learning disabilities, and child and adolescent mental health services. The ICS has an overriding focus on health inequalities and the wellbeing of the population. More examples can be found in the LGA’s Prevention Must Know.

Act as One: Bradford District and Craven Health and Care Partnership

Act as One is a place-based partnership in WYH ICS, serving a population of around 650,000 people. In 2018, commissioners, providers from all sectors and community organisations in Bradford District and Craven signed a Strategic Partnering Agreement (SPA) setting out a framework for roles, responsibilities, leadership and decision-making. An important principle was to devolve decisions as close as possible to where support takes place.

Since then, trust and relationships have deepened through joint working and the SPA has been updated. The principle of Act as One was coproduced to guide the partnership in its vision of people living ‘happy, healthy at home’ and to provide an identity and sense of ownership for those involved. In May 2021 the Act as One Festival provided a chance to celebrate achievements and share learning and best practice.

Examples include:

- the Reducing Inequalities in Communities programme was developed by a GP clinical lead working with primary care networks and other agencies. There are 21 projects focused across four life stages overseen by a multi-agency steering group. One of the projects is the multi-disciplinary and culturally competent proactive care team which works across organisations in central Bradford to provide primary care focused, short-term support to vulnerable, fail adults.

- The multi-agency integrated discharge team (MAIDT) supports the home first approach and links closely with the discharge to assess model. MAIDT supports the 20 per cent of patients who have more complex needs to be discharged from hospital on the correct pathway in a safe and timely way.

- The multi-agency support team (MAST) provides holistic support in the hospital setting and intensive support in the community focused on frequent attenders of A&E to help people transition from hospital back home. MAST is a voluntary and community sector led team supporting A&E around alcohol, mental health and frailty. In the past 12 months, MAST delivered 2,737 interventions in the acute trusts and delivered 1643 sessions to 865 people locally.

Within the SPA there are 13 community partnerships made up of primary care, social care, the voluntary and community sector and local communities. These proved invaluable in the partnership’s response to COVID-19, in reaching out to vulnerable communities to understand common anxieties, combat misinformation and provide targeted support. For example:

- Working with the Race Equality Network to provide a wide range of culturally sensitive information in accessible settings.

- A local version of SAGE called the Bradford COVID Scientific Advisory Group was set up to identify rich community level data about the pandemic using research from the longitudinal study, Born in Bradford, and information from community respondents. This allowed a swift understanding of how different communities in Bradford were affected and what would help.

The SPA will continue to develop as the ICS and place partnerships evolve their leadership, governance and working arrangements in the move to ICS statutory status.

References and resources

- DHSC (2021) ‘Integration and innovation: working together to improve health and social care for all’.

- DHSC (2021) ‘Health and Care Bill’.

- DHSC (2021) ‘Explanatory notes to Health and Care Bill’.

- DHSC (2021) ‘Building Back Better: Our Plan for Health and Social Care’.

- DHSC (2021) ‘Integrated Care Partnership engagement document and ICP FAQs’.

- Kings Fund (2021) ‘Developing place-based partnerships: The foundation of effective integrated care systems’.

- Kings Fund (2021) ‘Understanding integration: How to listen to and learn from people and communities’

- Kings Fund (2019) ‘Vision for population health’.

- LGA (2021) ‘Briefing: Health and Care Bill 2nd reading’.

- LGA (2021) ‘Response to Build Back Better: Our plan for health and social care’.

- LGA (2020) ‘Achieving integrated care through community and neighbourhood working: A high impact change model’.

- LGA (2019) ‘What a difference a place makes: the growing impact of health and wellbeing boards’.

- LGA, Adass, ADPH, NHS Confederation, NHS Clinical Commissioners, NHS Providers, (2019) ‘Shifting the centre of gravity: making place-based, person-centred care a reality’.

- LGA, ADASS, ADPH, the NHS Confederation, NHS Clinical Commissioners, NHS Providers (2019) ‘Six principles for achieving integrated care’.

- LGA and NHSCC (2020) ‘Localising decision-making a guide to support effective working across neighbourhood place and system’.

- LGA and SCIE (2019) ‘Achieving integrated care: 15 best practice actions’.

- NHS England, 2014, ‘How to guide the BCF technical toolkit’.

- NHSEI (2021) ‘Interim guidance on the functions and governance of the integrated care board’.

- NHSEI (2019) ‘NHS Long Term Plan’.

- NHSEI, LGA (2021) Thriving places: Guidance on the development of place-based partnerships as part of statutory integrated care systems.

SCIE resources:

The ‘Must Know’ series are a long-standing free downloadable web-based source of information on the key issues facing portfolio holders, such as integration, prevention and resources. Part of the LGA’s leadership development offer, they explore questions and challenges in key areas in health and adult social care from a member perspective and are updated on a rolling basis.