Introduction

Given the links between homelessness/housing and modern slavery, the LGA developed this document to provide focused guidance to assist heads of service and frontline officers in housing teams in understanding their role and improving their provision for victims of modern slavery.

The LGA has also produced separate modern slavery guidance covering councils’ wider role in tackling modern slavery, a chapter on housing in that document incorporates this guidance.

In this document, homelessness/housing services refers to services involved in homeless relief and the provision/management of housing and accommodation. While there are also important links between private sector housing enforcement and modern slavery, we do not address those issues within this document as they are dealt with by environmental health teams separately to homelessness and housing provision/solutions.

Evidence suggests that there are clear links between experiences of homelessness and modern slavery. Previous research suggests that homeless people are vulnerable to becoming victims of modern slavery, particularly where they have multiple or complex needs. Equally, victims of modern slavery may also be particularly vulnerable to becoming homeless where accommodation is linked to the work a victim is being forced to undertake.

This means that officers working in council homelessness/housing services, as well as the partner organisations they regularly engage with, may regularly come across victims of modern slavery, and those at risk of it. With a key role to play in identifying potential victims, services need to know how to respond.

Alongside this, in many cases councils will have a legal duty to provide accommodation support to victims of modern slavery. The Homelessness Code of Guidance was updated in summer 2021 to highlight the issues raised more clearly, so it is important that services are aware of the legal requirements and how they link into the dedicated national support available to victims of modern slavery.

This guidance therefore provides an introduction to modern slavery, outlines the key responsibilities and duties which apply to councils, and highlights ways in which homelessness/housing services can contribute to support for victims. It is one of two publications, including a set of case studies, which can be used separately but which are intended to form a single, comprehensive good practice guide.

Overview of modern slavery and links with homelessness/housing

What is modern slavery?

Modern slavery is a serious, often hidden, crime where people are forced by others into a situation which they cannot leave so that they can be exploited for profit. Under the Modern Slavery Act 2015, it includes any form of human trafficking, slavery, servitude, or forced or compulsory labour.

It involves using coercive means to control or exploit victims, including:

- Force, or the threat of physical force to victims or their family members

- Physical confinement or confinement through threats, where victims are unable to leave or seek help; this might include withholding travel or immigration documentation

- Deception, when a victim is given false information about their living or employment conditions in order to secure their consent

- Fraud, when a victim’s accounts or finances are controlled by their abusers, and victim’s names are attached to debts or illegal activities

- Grooming, where vulnerable individuals are enticed over time to take part in activities

- Debt bondage, where victims are forced to repay artificially for their travel costs, or for their accommodation

- Abuse of power or a position of vulnerability, eg if the victim has an irregular immigration status, is economically dependent or homeless, or has vulnerabilities in their physical or mental health.

Victims might be exploited for a variety of purposes, including:

- sexual exploitation, when victims may be forced into prostitution, pornography or lap dancing for little or no pay

- domestic servitude, where victims are forced to work in private households for very low or no wages, and without freedom of movement

- criminal exploitation, where victims are forced to take part in activities such as theft, benefit fraud, or drug production and running

- organ harvesting, where victims are trafficked in order for their internal organs (typically kidneys or the liver) to be harvested for transplant

- forced labour, where victims are made to work for very little or no pay, in dangerous or unpleasant conditions - common industries that victims are forced into include agriculture, factories, construction, hospitality, beauty salons, and car washes.

Further information on the meaning of, and identifying signs of modern slavery can be found in the Modern Slavery Act 2015 statutory guidance for England and Wales.

Addressing common misunderstandings and misconceptions

- People can be victims of modern slavery even when they have apparently consented, as consent can be obtained by coercion.

- Coercion can also mean that victims don’t take opportunities to escape. Despite this, they are still victims.

- Exploitation doesn’t need to have taken place yet for individuals to be victims, eg if their abusers are caught before the exploitation takes place – what matters is the purpose for which they’re being held.

- UK nationals can be victims of modern slavery: in 2020, there were more recorded British victims of modern slavery than of any other nationality. People can also still be victims of human trafficking even where they have only been moved within a country.

- Modern slavery victims could be related to or in a relationship with their abusers, eg if they are being groomed.

- Victims of modern slavery might say that they have a better situation than previously. Despite this, if they have been coerced by their abuser into exploitation, they are still victims of modern slavery.

Homelessness and modern slavery

People who are homeless may be more vulnerable to becoming victims of modern slavery, particularly if they have associated support needs. In 2015, research carried out for Lankelly Chase found that each year, over 250,000 people in England have contact with at least two out of three of the homelessness, substance misuse and criminal justice systems and at least 58,000 have contact with all three. The report also found that people experiencing some combination of these disadvantages had a much stronger prevalence of mental health needs and social isolation.

Analysis by the modern slavery helpline of their cases between October 2016 and April 2019 found that victims who experienced homelessness before exploitation most commonly experienced poverty, substance abuse, and immigration status (including no recourse to public funds) as additional vulnerabilities.

These factors may impair judgement or people’s ability to protect themselves; they may also enable traffickers to lure people into situations of exploitation with the promise of better living conditions, shelter, and basic subsistence. Recent research by Project TILI, based on data taken from homelessness, housing, sex work, and domestic abuse charities, found that the survivors they engaged with had overwhelmingly been living in accommodation tied to their exploitation. This included almost all recorded cases where victims had been sleeping rough or in unsuitable temporary accommodation before their exploitation: very often, victims moved into accommodation linked to their exploitation, such as brothels, overcrowded houses of multiple occupation, or cannabis farms.

Victims of modern slavery are also vulnerable to becoming homeless as a result of their exploitation, due to a lack of social networks or a lack of available accommodation after exiting the national asylum support service. Project TILI data found that, in one fifth of the recorded cases where people did get support from the National Referral Mechanism (see next section), people were still homeless after exiting this support. This in turn leaves victims vulnerable to re-exploitation.

Cuckooing, housing and modern slavery

In recent years there has been a growing trend of ‘cuckooing’, whereby criminals and traffickers exploit often vulnerable individuals by effectively moving into their property and using it as a base for criminal activities, typically supplying drugs but also cannabis cultivation. This type of exploitation can occur in any tenure of property, but council teams working with the provision of social housing should be alert to reports which could indicate cuckooing, for example regular reports of anti-social behaviour, and where applicable make links with other services and agencies.

National Referral Mechanism and victim support

National Referral Mechanism

The government’s statutory framework for identifying and supporting modern slavery victims is called the National Referral Mechanism (NRM). Potential victims can be referred into the NRM by designated bodies, known as first responders, including:

- councils

- police forces

- immigration enforcement

- border force

- some third sector organisations working with victims of modern slavery.

The Home Office has developed training for first responder organisations, hosted by the Police Modern Slavery and Organised Immigration Crime Unit website.

Under section 52 of the Modern Slavery Act, first responders have a ‘duty to notify’ the Home Office about potential victims of modern slavery. This generally means making detailed referrals about potential victims into the NRM. However, where a potential adult victim has not provided their informed consent to be referred, first responders should provide a notification to the Home Office, rather than a full referral; this can be submitted anonymously. Referrals can be made via the online NRM portal.

Recent analysis by Project TILI of data submitted by homelessness, housing, and domestic abuse charities, found that nearly half of recorded potential victims did not want to be referred to the NRM. The project report suggests that this can happen for a number of reasons, including:

- victims not trusting authorities, eg due to previous negative experiences of being let down by services, or due to worries about their uncertain immigration status

- victims feeling that the support provided is too short term

- victims not identifying as ‘victims’, and not feeling that they need support from the NRM

- victims fearing retaliation from their exploiters if they disclose details.

In cases where they do not enter the NRM, victims may be disadvantaged by a lack of practical and emotional support to recover from the experience of modern slavery.

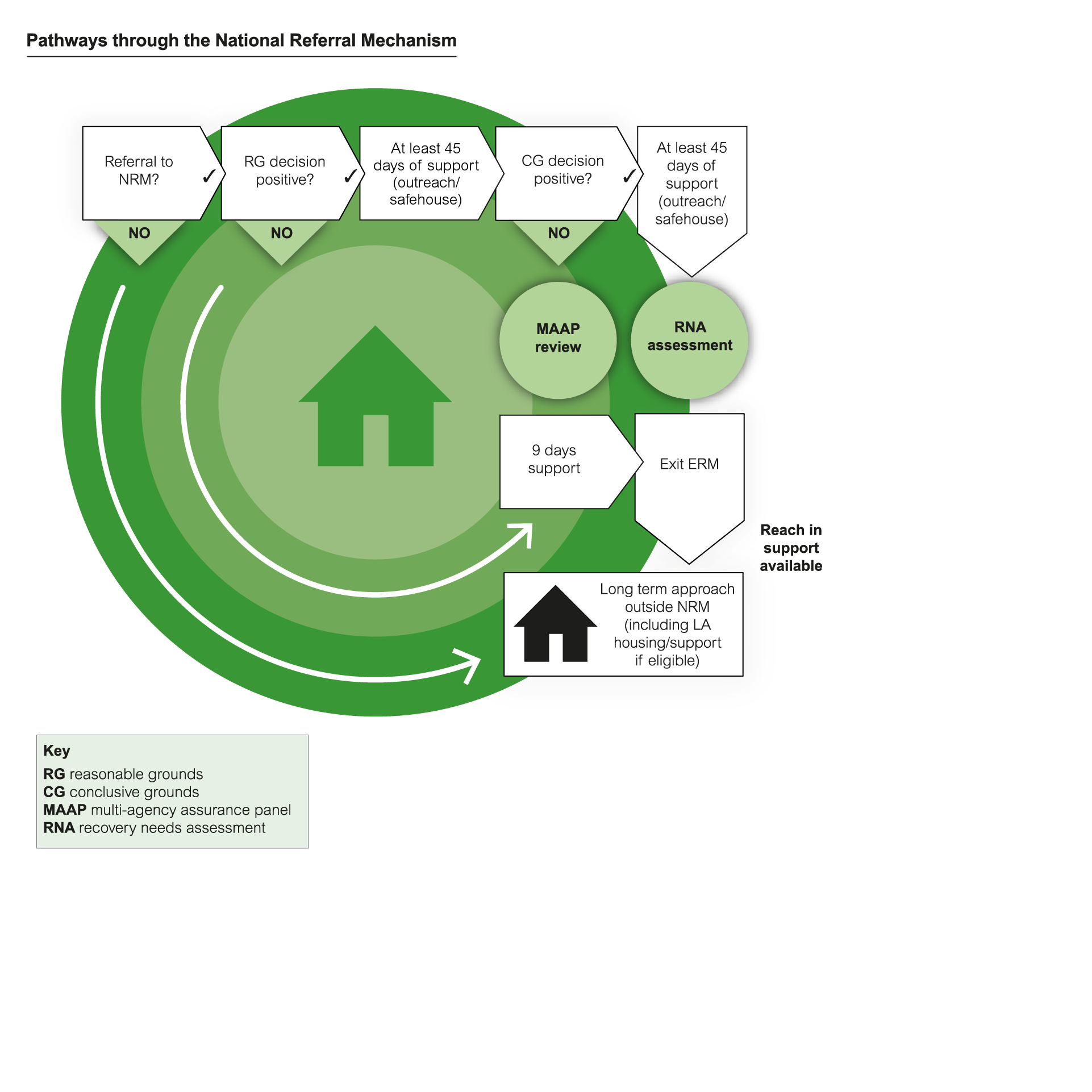

Frontline staff are not expected to conclusively prove that someone is a victim of modern slavery. Instead, councils' (and other first responder organisations) duty as first responders is to identify people who they are concerned might be potential victims and refer them to the NRM. Full referrals into the NRM are submitted to the Home Office’s Single Competent Authority (SCA), or the Immigration Enforcement Competent Authority for referrals relating to foreign national offenders which will initially consider whether people referred are possibly victims of modern slavery: the threshold at this stage is that of ‘I suspect but cannot prove’ that an individual is a victim of modern slavery. This is known as a ‘reasonable grounds’ decision, and should be made within five working days of a referral, although in practice it can take longer.

Where a reasonable grounds decision is negative, an individual will be exited from the NRM process within nine days of the decision without any further support. If a reasonable grounds decision is positive, the potential victim will be entitled to at least 45 days of support provided through the national Victim Care Contract (VCC), through which victims can access outreach services including legal, practical and emotional support, and safehouse accommodation if they are destitute. The Home Office has commissioned The Salvation Army (TSA) to provide victim care services across England and Wales through a network of sub-contractors, including its own Direct Delivery Service.

During this 45 day period, the SCA will undertake further work to enable it to make a ‘conclusive grounds’ decision on whether someone is ‘more likely than not’ a victim of modern slavery. In practice, it can take much longer than 45 days for potential victims to receive a decision.

If victims receive a positive decision, they are entitled to at least a further 45 days of additional support before exiting the NRM and VCC: support needs are identified through the process of undertaking a personalised recovery needs assessment (RNA) identifying the specific support needs an individual has to help them recover. If the conclusive grounds decision is negative, individuals are entitled to a further nine days of support before being required to exit the NRM/VCC.

All negative conclusive grounds decisions are automatically referred to multi-agency assurance panels for review; although they cannot overturn decisions, they can ask for a case to be reviewed where they believe that the decision has not been made in line with competent authority guidance.

Once a victim has exited the main Modern Slavery Victim Care Contract (MSVCC) support service, they may still access reach-in support if they have emerging or reactive requirements for support or advice.

- Between 1 July and 30 September 2019, 2,808 potential victims were referred to the NRM – a 61 per cent increase from the same quarter in 2018.

- In 2020, the Home Office made 10,608 reasonable grounds decisions and 3,454 conclusive grounds decisions. Of these, 92 per cent of reasonable grounds decisions were positive, and 89 per cent of conclusive grounds decisions.

- Of potential victims referred to the NRM in 2020, the most common nationality of all referrals was British, accounting for 34 per cent of all potential victims. Albanian nationals were the second most referred at 15 per cent of referrals, followed by Vietnamese nationals at 6 per cent.

- Not all potential victims are referred to the NRM (figures show there are consistently duty to notify referrals numbering in the several hundreds each quarter) or are even identified. Consequently, the true scale of modern slavery is hidden – estimates range from 10,000 victims in the UK in 2013, to 136,000 victims in the UK in 2018.

Victim support

As set out above, The Salvation Army and its network of sub-contractors provide support services to adult victims of modern slavery in England and Wales through the MSVCC. There are two models of support: safehouse based support and outreach support. Alongside this, victims may have separate legal entitlement to access local services provided by councils under a range of different frameworks including homeless and safeguarding/ wider social care legislation, as well as other agencies such as health services. This section provides a brief overview of relevant legal frameworks for supporting victims of modern slavery, with a particular focus on local authority housing and homelessness services.

It is important to note that some cases of exploitation and slavery can be historic, but that this does not affect a victim’s entitlement to support.

Domestic legislation

Housing Act 1996

Under the Housing Act 1996, local housing authorities may owe victims of modern slavery a range of duties.

- Prevention/relief duty: as set out in this document, victims of modern slavery who are in the NRM process are expected to exit the Victim Care Contract following a period of at least 45 days move on support following a positive conclusive grounds decision. During this time, victims might be owed the prevention or relief duty, such that councils must take reasonable steps to try and prevent their homelessness or relieve it if they are already homeless. The Code of Guidance suggests that councils should maximise the chances of successfully preventing homelessness by establishing arrangements with NRM support providers for early identification.

- Duty to provide interim accommodation: victims of modern slavery might already be homeless when making their homelessness application. If local housing authorities have reason to believe that applicants may be homeless, eligible for assistance, and in priority need, they should ensure that interim accommodation is available. This might apply during the period following a referral to the NRM, while applicants are still waiting for an initial reasonable grounds decision, or while the local housing authority is carrying out its enquiries.

- Main homelessness duty and priority need: people who have been victims of trafficking and modern slavery might be vulnerable, and therefore under the Homelessness Code of Guidance have a priority need for accommodation. The guidance states that local housing authorities should take advice from specialist agencies, including NRM support providers, drug and alcohol services, local charities, and the police, who are supporting applicants.

The Homelessness Code of Guidance was updated in summer 2021 specifically to reflect these duties more clearly.

The updated code of guidance also highlights that homelessness applicants may have been forced to leave the area where they have a local connection. It states that local housing authorities must not refer applicants to other authorities if they would be at risk of violence or domestic abuse in that local area.

Care Act 2014

Adult social care services can be a route of possible support for victims of modern slavery or human trafficking, not least because some groups falling within the remit of the services – for example, individuals with learning difficulties or experiencing mental health issues – can be more vulnerable to becoming a victim of slavery in the first place.

The legal framework, approach to and process for adult safeguarding is set out in the Care Act 2014, which recognises modern slavery as a category of abuse. Councils are responsible for looking at any safeguarding concerns for adults who have care and support needs and who are unable to protect themselves, and then deciding whether it is necessary for them or a local partner to carry out an enquiry. A ‘Section 42’ enquiry, which relates to adults who have care and support needs and are unable to protect themselves, will be carried out if abuse or neglect is or is at risk of taking place, and to help decide what should happen to help and support the individual. The circumstances of each case will determine the scope of each enquiry, as well as who leads it and the form it takes. Victims of modern slavery may not have care and support needs as defined by the Care Act, and councils and their partners may put different wrap around support structures in place to ensure victims and survivors' needs are met.

The MSVCC provides support for victims’ needs arising from their experiences of modern slavery, but not for other needs or conditions (eg disabilities or addictions) which predated this. This may mean that some individuals referred into the MSVCC with wider care and/or accommodation needs might need to be assessed and have their care needs met by local statutory partners under the Care Act or other legislation (for example, for providing accommodation with specific adaptations for people with disabilities) with this to be decided on a case by case basis.

Children Act 1989

The Children Act is relevant to housing services because section 17 of the Act places a general duty on councils to ‘safeguard and promote the welfare of children within their area who are in need.’ Any service provided under section 17 may be provided to the family or for any member of a child’s family if it is provided with a view to safeguarding or promoting the child’s welfare. In practice, this means that where victims themselves may not be owed a housing duty, it is possible that housing assistance is owed by the council under child protection duties if the victim has a dependent child. There will therefore need to be links and referral pathways between housing and children’s services to help identify this.

Localism Act 2011

The general power of competence introduced in the Localism Act provides councils the same broad powers as an individual to do anything unless it is prohibited by statute. Councils have been encouraged to use this power to provide support for victims of modern slavery who do not otherwise have entitlement to access local services, although resource pressures can make this challenging. Further, the general power under the Localism Act cannot be used to override prohibitions on the provision of support under other legislation.

International treaties and conventions

The UK has signed up to the following treaties which have shaped the national approach to modern slavery:

- The Council of Europe Convention on Action Against Trafficking in Human Beings 2005 CETS 197 (ECAT)

- The EU Directive on Preventing and Combating Trafficking in Human Beings and Protecting its Victims 2011/36/EU (the Anti-Trafficking Directive)

- The European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR)

Article 12 of ECAT requires that signatories adopt measures to assist victims in their recovery, including appropriate and secure accommodation, while article 11 of the Anti-Trafficking Directive requires the state to provide ‘assistance and support’, including the provision of ‘appropriate and safe accommodation and subsistence’ as soon as a person is ‘indicated to be trafficked’ while ECAT also sets out support requirements for victims. These responsibilities are primarily met through the victim care contract, however the definition of ‘the state’ also includes councils.

The NRM was set up to incorporate the Convention on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings in the UK. However, the UN Human Rights and Human Trafficking Fact Sheet 36 is clear that international treaties may be enforceable in domestic law and expectations can therefore extend beyond NRM support:

“Treaties [which includes conventions] are the primary source of obligations for States with respect to trafficking. By becoming a party to a treaty, States undertake binding obligations in international law and undertake to ensure that their own national legislation, policies or practices meet the requirements of the treaty and are consistent with its standards. These obligations are enforceable in international courts and tribunals with appropriate jurisdiction, such as the International Court of Justice, the International Criminal Court or the European Court of Human Rights, and may be enforceable in domestic courts, depending on domestic law”.

Recent cases and case law indicates that decisions can refer to international conventions and human rights legislation and, even if an international convention is not directly enforceable, it may be considered in interpreting the scope of obligations under domestic legislation. As a result councils should therefore be mindful of how these treaties can be interpreted as applying to their own obligations.

The LGA has raised with the Home Office that some of the international commitments the UK has signed up to may appear to go beyond what is set out in the domestic legislation that councils apply in relation to adult victims. We have emphasised the pressing need to ensure that the international duties the UK is bound by, and case law relating to it, are reflected in UK law, whether the law is covering homelessness, safeguarding and social care, or any other type of support that might be sought for victims. This would help to ensure that there is clarity and understanding about the support that should be provided and by whom. Alongside that clarity, should also come the funding to support it, with councils to date having received no new burdens funding to support victims of modern slavery.

Overview of current issues with victim support

There are a number of challenges in the provision of support to victims of modern slavery.

Partly due to rising number of British victims referred into the NRM, in recent years there has been a trend towards changing patterns of victim support, most notably in relation to housing. While there was previously a widespread presumption that all victims would be housed within the MSVCC it is now clearer (including in the statutory guidance on the Act) that, where they have entitlement to other housing support, adult victims should receive MSVCC support through outreach services provided while they remain in local authority or other housing, rather than moving into MSVCC safe house accommodation, which may not always be the best option for the individual in the longer term, for example if it would result in them losing an existing tenancy. This has sometimes led to disagreements between councils and MSVCC sub-contractors over responsibility for housing victims, with a particular pinch point when victims have initially been identified. At the other end of the NRM process, there are reports of challenges for victims coming out of MSVCC services and into local services as they move through the process of recovery.

The statutory guidance on the Act sets out the following principle of support provided through the MSVCC:

This document is intended to help raise awareness and understanding of modern slavery and councils’ homelessness/housing obligations, so that lack of awareness is not a barrier to victims receiving support. However, even with good understanding and awareness, there are some fundamental issues for councils to try to overcome:

- Access to suitable accommodation for victims – whether potential or confirmed – can be one of the biggest challenges for councils due to a lack of availability and high costs. Some councils, such as those in Humberside, have tried to address this by pooling their supply of emergency accommodation with neighbouring councils, or by working with police and crime commissioners, who in some areas have funded dedicated emergency accommodation.

- Local connection for potential victims can sometimes be unclear, even where priority need is accepted; for example, victims may need to move area if the previous place they lived was unsafe due to a risk of exploitation so may have limited connection with an area. Victims might also be in safehouse support for a significant amount of time and become familiar with the area. This might affect their willingness to resettle in a different area when they enter post-NRM support. This can be a barrier to finding them somewhere suitable to resettle.

- It can be challenging to support victims with no recourse to public funds (NRPF), which can increase the chances of their re-exploitation, although some councils have used rough sleeping funding to help support this group.

- Victims might find that leaving the Victim Care Contract can be a sudden change, with much less support. After litigation in 2019, the VCC now provides continued support to people who still need it after their conclusive grounds decision. However, there is still no funding for mainstream support for victims of modern slavery outside the VCC and it can be challenging to access the right support for victims; and even where it is available, it might be unsuitable or inappropriate.

In 2017, the Home Office worked with six councils to pilot different approaches to post-NRM support; at the time, VCC support was still provided on a time limited basis ahead of the introduction of the recovery needs assessment process.

The six pilot areas all had a focus on supporting victims to become independent, feel safe and integrate into the community and providing suitable, sustained accommodation. Two of the pilots focused on housing in particular; Birmingham council commissioned Spring Housing, a housing charity, to provide short-term shared accommodation, whilst arranging long-term tenancies which would extend beyond the life of the pilot, while in the London Borough of Redbridge specialist housing assessment officers, a resettlement officer, and advocacy support helped to ensure victims had safe accommodation. In Leeds, specialist advocates helped victims to link with local services, with the council’s pilot subcontractor working with the council’s housing team to source settled housing while victims were in interim housing.

The pilots provided much valuable learning, including that the pilot areas needed to raise awareness of modern slavery with mental health and drug and alcohol services to ensure that support could be made available despite normal criteria and thresholds. In relation to housing, the projects highlighted the positive impact that dedicated funding provided as part of the pilot processes had in enabling support for victims: one authority highlighted the issue of being able to provide accommodation during the funded pilot period that it was clear a victim would not be able to sustain when the pilot funding ceased due to the limitations of what could be afforded through the local housing allowance.

Further information is available in the pilot evaluation report.

Implications for housing services

As the previous sections of this guidance have shown, it is clear that homelessness and housing services may come into contact with victims of modern slavery and may also have statutory duties to support them. This means that service leads need to have a clear understanding of how to manage modern slavery as an important part of overall service delivery. There are various components to doing so successfully:

- awareness raising: ensuring staff receive training in understanding modern slavery, its indicators and how to spot the signs of it

- building understanding: providing staff with an understanding of the legal framework for victims of modern slavery as well as of how to take a supportive, person-centred approach to their needs

- internal collaboration − linking the work of homelessness/housing teams with other council teams with a role in responding to modern slavery, given the cross-cutting nature of this work

- external partnerships: working closely with local voluntary and community sector organisations that work with victims, as well as linking into council partnership work with agencies such as the police, health etc.

The rest of this section provides guidance on the steps that services can take to help develop a comprehensive homelessness/housing service response to modern slavery.

Awareness raising

A wide range of frontline council staff could come across and identify possible victims of modern slavery in the course of their work, including homelessness/housing teams, regulatory officers and customer service staff, and councils may therefore already have a corporate approach to modern slavery training across different teams. However, the homelessness code of guidance emphasises that homelessness decision makers ‘should be alive to the possibility that applicants for assistance under Part 7 are victims of modern slavery, or are otherwise vulnerable’ to help them meet their obligations.

Homelessness/housing teams should ensure that training is made available for their officers focusing on specific issues relevant to homelessness and housing. raining could include face to face training, e-learning, assessment tools or checklists to help trained staff to spot the signs of modern slavery and correctly refer them for appropriate support. As a minimum, it should cover:

- what modern slavery is

- the indicators of modern slavery, and how staff can spot the signs in a variety of situations including homelessness/housing scenarios

- the NRM and duty to notify

- the council’s approach to managing modern slavery and what to do when a possible victim is identified (including how referrals can be made internally and to the Single Competent Authority under the duty to notify) – see later section on internal collaboration

- the support available to victims, including the homelessness code of guidance sections on modern slavery

- local and national partners the council can work with to ensure appropriate support is provided to victims.

Many third sector partners offer training on modern slavery, and there are various resources already available to assist councils in providing advice and guidance to their teams. A selection is highlighted here and additional resources are listed in the annex at the end of this document; additionally, some key signs/indicators from a homelessness/housing perspective are featured below:

- Anti-Slavery International has published an overview of modern slavery.

- The charity Unseen has summarised possible indicators of different types of exploitation.

- Statutory guidance on the Modern Slavery Act provides detailed information about modern slavery and the legal support which victims are entitled to.

- The Home Office has published an overview of the NRM and duty to notify, as well as an e-learning package for first responders. This SCA presentation to an LGA webinar on NRM referrals also provides helpful information.

- The homelessness code of guidance was updated in 2021 to provide specific sections on modern slavery.

Knowing the risks and spotting the signs

People of any nationality or background could become a victim of modern slavery, however some groups are recognised to be more vulnerable than others. Staff should be aware that perpetrators are most likely to target people that they perceive as vulnerable, including people:

- with alcohol or drug dependencies

- with learning disabilities

- with existing mental health problems

- experiencing homelessness or destitution

- who can’t speak the local language or lack local networks

- who aren’t aware of their immigration, labour, and welfare rights

- seeking asylum or subject to immigration control, including people who have no recourse to public funds, who have been dispersed to Home office accommodation, or who have been recently awarded refugee status but have not yet been able to transition onto mainstream benefits.

Possible indicators that may be observed by people working in homelessness/housing services include individuals who:

- have no identification documents, or false documents

- can't confirm any names and addresses of contacts, or a home address in the UK

- are worried about revealing their immigration status, or lack knowledge of their immigration status

- go missing on occasions

- are known to beg for money

- might be experiencing post-traumatic stress disorder, resulting in hostility, aggression, poor memory or concentration

- present as anxious, scared, or withdrawn

- are reluctant to engage with authority figures or provide personal details, or the details of their employer

- have a prepared story, similar to that given by others, or give an inconsistent or obviously incorrect story

- show signs of injury, malnourishment, weakness, or poor hygiene.

External awareness raising

Councils should also consider how they can raise awareness of the risks of exploitation amongst local communities, and especially amongst the homeless and those working with them. People working with the homeless community should be alert to perpetrators targeting homeless communities, including people sleeping rough, in shelters, in day centres, or at soup kitchens: this could involve people being offered work, a place to stay, or access to drugs or alcohol. In some cases, perpetrators have been known to pose as homeless people. Ensuring a wide level of awareness can enable a much wider range of people to spot the signs of modern slavery and report potential cases, as well as enabling homeless people to keep themselves safe from exploiters, or to recognise their own experiences as potential victims of modern slavery and seek support.

Raising awareness might include:

- displaying information in various languages in council offices and in supported housing schemes

- hosting social media campaigns

- running an awareness-raising event

- displaying information on the signs of exploitation in tenants and residents’ associations

- including information in council newsletters

- hosting sessions at local residents’ forums.

Councils could also partner with the police and other partners to host information sessions at accommodation services or day centres. The 2017 report commissioned by the Independent Anti-Slavery Commissioner highlights one example of an organisation hosting a police session at their day centre, which resulted in several people coming forward to talk about their experiences of being approached by traffickers.

Building understanding and person-centred processes

Alongside an understanding of what modern slavery is and how victims may present to councils, it is essential that homelessness/housing teams have a clear understanding of the entitlement of victims to support. The homelessness code of guidance has been updated to highlight the issues raised by modern slavery and victims may well have a priority need under the Housing act 1996 on the basis of vulnerability. Service leaders should ensure that all staff receive appropriate guidance and training on this.

Individuals who are vulnerable as a result of being a victim of modern slavery would have priority need for housing. If housing authorities believe that this may apply they should ensure that interim accommodation is provided while they carry out their enquiries and/or the individual waits for a reasonable grounds decision if an NRM referral has been made.

Victims may also be owed a full housing duty after the prevention/relief duty has run its course, which would entitle victims to longer term housing after temporary accommodation.

Finally, victims with no recourse to public funds who are not owed a housing duty under the Housing Act may still be eligible for support under section 17 of the Children’s Act if they have a family and dependent children.

Disclosure policies

Depending on the point at which a victim is in contact with the council, homelessness/housing services should think about what information is required to demonstrate that they have been a victim. Disclosure and retelling their experiences can be deeply traumatic for survivors. If an individual already has a conclusive grounds decision, or even a reasonable grounds decision with a conclusive grounds decision pending, council teams should consider whether it is necessary for a victim to provide the same information to the council; an NRM decision from the SCA could be accepted as sufficient evidence of the victim’s experience.

Where a victim has not entered the NRM, councils could also consider whether an individual is working within any other services or charities that similarly may be able to share information about the victim’s experience, so that the victim does need to retell their story to multiple agencies. Sheffield council has identified a local voluntary and community sector (VCS) organisation as a trusted assessor, meaning it is able to complete the council’s homelessness assessment form on behalf of a victim, who is then not required to go through their experience again with the council team when they are already working with a specialist modern slavery organisation.

Victims may also require support from their support worker during interviews and in completing applications, therefore where consent is given, the support worker should be enabled to liaise with the local authority directly, on behalf of the victim. Information that other agencies supporting the victim have provided should be taken into account when making the assessment and care should be taken not to repeat requests for information that has already been provided, to reduce the risk of retraumatisation."

- Para 25.21, trauma-informed approach – homelessness code of guidance

Working sensitively with potential victims

Where a homelessness/housing team is the first agency that a victim has shared their experience with, this will of course need to be handled sensitively and with care. The Trauma-Informed Code of Conduct for All Professionals Working With Survivors, produced by the Helen Bamber Foundation, sets out guidance for how interactions with victims should be handled; similarly, the Human Trafficking Foundation’s Survivor and Trafficking Survivor Care Standards also provide comprehensive guidance for providing support in an effective, person centred way.

Being a victim of exploitation or modern slavery can be a deeply distressing or traumatic experience, which can have lasting effects.

Councils should make sure that their work with potential victims – right from the first contact and risk assessment – takes account of potential trauma and the impact that this might be having.

Councils can do this by:

- Working to put potential victims at ease, with a supportive attitude and body language.

- Displaying cultural sensitivity – ensuring that assessments are done in a culturally sensitive and tactful way. This might also involve securing interpretation services

- Making sure that the physical environment and immediate location is safe, and attending to immediate physical needs, including pain, hunger, and sleep deprivation.

- Providing reassurance about confidentiality, and making sure that potential victims understand that information cannot be shared without their informed consent, unless there is an immediate safeguarding risk.

- Ensuring and checking that potential victims understand the process at every stage. This includes empowering potential victims by helping them to understand the support that they might be able to access, and highlighting where they have choice and agency.

- Ensuring that potential victims do not have to repeat their story multiple times – recounting the details of their exploitation can be a traumatising experience for potential victims. Councils should ensure that victims are only required to tell their story once, and that the modern slavery coordinator is in a position to share information with other partners where needed.

- Building a trusted relationship – potential victims of modern slavery might not trust authorities, or might not self-identify as a victim of exploitation. As a result, it can take time for potential victims to build the confidence to disclose their story and needs. It is therefore important that councils can provide continuity of support, including by assigning an individual, named single point of contact who is responsible for coordinating multi-agency case work for a given victim.

Decision making

The speed and way in which councils reach decisions on housing support for potential victims of modern slavery is also important. While councils strive to make all decisions on housing support as swiftly as possible, a quick decision is particularly important in relation to those who have experienced modern slavery: securing accommodation is an important step in reducing the risk of re-trafficking and beginning the process of recovery.

One example is in relation to the local connection criteria, which councils have discretion to apply. It will always be helpful for a council to begin the decision making as soon as possible to enable clarity for the individual at the earliest opportunity.

A related point on local connection is the value of working with other partners, whether that is other councils which may owe the individual a duty, local agencies who may have had some involvement with or be able to support the potential victim, and also internal council partners (see internal collaboration section below). Westminster City Council have worked with local homelessness charity The Passage to develop a multi-agency case conference approach to victims of modern slavery identified within homelessness/housing services.

Westminster/The Passage multi-agency case conference (MACC)

The aim of the MACC approach is to provide proactive, preventative relief that helps to prevent re-trafficking and re-exploitation. When a potential victim is identified by The Passage or within Westminster, a MACC is arranged within 48 hours bringing together the following partners:

- The Passage

- Westminster Council Adult Social Care

- Westminster Council Rough Sleeping Team

- an immigration advisor (if appropriate)

- an NHS nurse (Homeless Team) (if appropriate)

- police (if appropriate)

- pre-NRM safe house case worker (if appropriate)

- any other key workers from external agencies providing support to the potential victim (PV).

The aim of the MACC is to agree an action plan for the victim setting out the steps different partners will take, and the MACC may cover the following issues:

- a risk and vulnerability assessment and wider needs assessment

- the health and mental health of the potential victim

- support provided by The Passage

- emergency accommodation and who is providing it

- capacity to consent

- referral into the NRM or duty to notify, and the lead first responder for this

- any legal issues (eg, immigration status, involvement in criminality), and

- whether the victim has children and what support is required.

View the rest of Westminster City Council's case study

Accommodation requirements

A further issue for service leaders to consider, ahead of the point of need, is what accommodation can be made available to victims when they are identified and a duty is recognised.

This can be a challenging issue for many councils, with significant shortages of housing stock or suitable temporary accommodation impacting the availability of suitable accommodation, and limitations on the type of accommodation that housing allowances will support. However, this emphasises why it is important that councils have undertaken some planning regarding what they might draw on, and how they might mitigate any shortcomings in what is available.

The individual circumstances of the victim will impact the type of provision that is required and appropriate: the accommodation needs of a young person, potentially still living with their family, who needs to be distanced from a situation of exploitation are significantly different to a single person who may already have moved away from where their exploitation took place. Insofar as possible, any provision made should try to reflect and respond to the specific needs of an individual.

Considerations should include:

- What options there are for housing victims locally, or outside of the area if local accommodation is not safe for the victim given the circumstances of their exploitation. If none are available, how can accommodation be arranged elsewhere – can this be agreed with a nearby or other council?

- What type of accommodation is available to the council? Is it shared accommodation; and if so is it mixed or single sex; for some victims, this will not be suitable.

- What additional support packs can be provided to help meet basic needs at the point of identification, wherever victims are housed, eg, clothes, toiletries, food?

- Is there an external partner – whether an alternative council, or a VCS organisation – that may be able to provide support with wraparound care and potentially accommodation?

As borne out by our accompanying case studies, different areas have taken different approaches to try to meet needs at the point when a victim is initially identified, including:

- several areas have commissioned dedicated emergency accommodation to support victims of modern slavery while they consider whether to enter the NRM: sometimes this is funded by local police and crime commissioners

- the provision of support packs to victims

- local agreements to house victims in neighbouring boroughs while cases are considered

- permitting teams to procure hotel accommodation for victims for an interim period

- working closely with local homeless charities to provide dedicated support for victims.

Internal collaboration

As modern slavery is an issue that intersects with the work of councils in many different ways, councils are strongly encouraged to identify a modern slavery coordinator, or lead team, responsible for joining up modern slavery work across different teams including community safety, regulatory services, homelessness/housing, and children/adult services. Modern slavery coordinators may sit in a variety of teams, but are often based within community safety, safeguarding or central policy teams.

The key objective of having a council wide coordinator and/or working group is to help agree and manage a council wide approach to dealing with suspected cases of modern slavery, including referral pathways between different services, an approach to the first responder role and submitting NRM referrals, and the collection of data on cases and NRM referrals. The coordinator can also act as a first point of contact for queries from within the council, for example where staff feel they may have come across a case, as well as for external agencies.

Service areas such as homelessness/housing could also consider appointing a service lead or leads who are primarily responsible for handling or dealing with suspected cases as they arise, and for engaging with colleagues working on modern slavery elsewhere in the council and externally. This can help to develop a core of expertise within the service and build relationships with other partner services and agencies. Councils may also seek to create working groups bringing together individual service leads for modern slavery.

A key issue for homelessness/housing services will be to ensure understanding of their council’s referral pathways for victims of modern slavery (covering victims who do, and do not, consent to enter the NRM), how they fit within it and can support it most effectively. The purpose of a referral pathway should be to ensure that no matter how a victim comes into contact with a council – and it could be through one of several different ways – they are treated consistently.

Referral pathways within a council will vary depending on how councils have established their internal structures for managing modern slavery, whether the council is unitary or two-tier, and on the range of local multi-agency partnership arrangements which have been set up to tackle modern slavery.

The key point for homelessness/housing services, will be to ensure that

all frontline staff are aware of their council’s modern slavery referral route so that they know what to do when they encounter a victim of modern slavery; not just in terms of the council’s obligations in terms of housing support, but also in terms of how the modern slavery aspect of the case will be dealt with, ie:

- Who else within the council should be notified of the suspected case – is a safeguarding referral required, and should a modern slavery coordinator be notified?

- Who will take responsibility for working with a suspected victim to discuss an NRM referral, if the council is acting as the lead first responder – does this role sit with the team that identified a possible victim or another team?

- What engagement, if any, is required with any external agencies in relation to the case?

Homelessness/housing services should also consider how they can receive and process applications where victims of modern slavery are identified by another service – i.e. how can victims be easily referred into the homelessness/housing team? In these circumstances, it may be helpful for there to be a dedicated email address or identified team members who can specifically deal with assessing the housing needs of suspected victims of modern slavery in a timely way.

In a two-tier area, councils should agree joint working arrangements, so that referral pathways are joined up and different services, including housing and social care, can link up effectively across the area.

External partnerships

Establishing links with partners, including local statutory and voluntary services, can help to raise awareness of the council’s work, and highlight named officers within the council whom partners can contact if they encounter a suspected victim of exploitation. Homelessness /housing services should seek to ensure that they are joined up with relevant external partners who can help ensure a stronger response for victims of modern slavery in their areas, as well as more coordinated work on modern slavery overall.

As a minimum, it will be helpful for councils to understand which third sector partners are working with victims of modern slavery in their areas: this may be as part of the victim care contract (for example, local safehouses or outreach support), but it may also involve work by anti-slavery charities outside the VCC support framework. Clearly, these organisations will come into contact with victims of modern slavery, often before an NRM referral has been considered, and it will be helpful for them to understand how to link into the council in order for victims to be referred for any support to which they are entitled.

Equally, anti-slavery charities will be able to assist councils with specialist expertise and advice and in developing a better understanding of the needs of modern slavery victims. Knowing the map of anti-slavery charities operating in the local area, and having established links to them, will help to build and strengthen relationships and should facilitate a swifter, and smoother, response when dealing with victims, particularly at the point of identification or when an individual may be approaching exiting NRM accommodation.

Homelessness/housing teams can work jointly with their modern slavery coordinator or lead to seek to develop these relationships if they do not already exist and agree how they will be best be managed. However, feedback from third sector organisations is that it is helpful to build direct relationships with homelessness/housing teams so that contact can be made quickly to discuss individual cases and needs.

Although information about some aspects of the VCC (for example the location of safehouses) is understandably sensitive, The Salvation Army are keen to develop closer links between their sub-contractors and councils. To find out about local VCC services in your area, councils can contact Marc Nicholls, Partnership Manager [email protected] or [email protected]

Homelessness/housing teams are already likely to have relationships with local homelessness charities; as set out above, these groups should be included within local awareness raising efforts, with information shared through local homelessness forums.

At the individual case level, some areas are starting to develop a MARAC (multi agency risk assessment conference) approach when suspected victims of slavery have been identified, a best practice approach that brings together different partners to consider what actions need to be taken. Homelessness/ housing services can play a helpful role if linked into any local partnership/MARAC style arrangements that have been put in place to manage individual cases of modern slavery and arrange multi-agency support.

More broadly, multi-agency working and effective information sharing between local partners can also aid in the detection of traffickers and potential victims of modern slavery. Councils should work with other statutory bodies such as local police and health services, job centres, national agencies such as the Gangmasters and Labour Abuse Authority, Immigration Enforcement, as well as VCS partners, to share intelligence on risks and relevant operations. While homelessness/housing services may not be directly engaged in these strategic partnerships, rather than individual case work, it will be helpful to be aware of wider partnership working through the council’s modern slavery lead. All council services should be aware of their responsibilities and the practical contributions and resources which they can make to multi-agency partnership working and support.

The Human Trafficking Foundation brings together a national network of modern slavery partnership coordinators to provide a forum in which to promote inter-regional cooperation and sharing of best practice between regional partnerships across the UK. Details of the different regional partnerships are available on their website.

Further information on providing housing support to victims of modern slavery

There are various points in a victim’s experience where homelessness/housing teams may come into contact with them. This has typically been when a victim has been able to leave their situation of exploitation and is homeless but has not yet been referred to the NRM; however, contact may also be made at a point when an individual will shortly be or has already left NRM accommodation.

There is scope to strengthen partnership working between VCC providers and councils to help smooth out the transition between local authority housing and VCC accommodation and vice versa. Homelessness/housing teams should consider these two stages in particular and think about the processes and provision that will be most important to supporting victims at these stages of their recovery.

As per previous sections of this guidance, when thinking about victims in the timeline of NRM support it is important firstly, to remember that not all individuals will consent to enter the NRM, or do so immediately after identification if they do choose to; and secondly, to recognise that even with an NRM referral and positive reasonable grounds decision, there may still be an expectation that a victim will be housed by the local council if they are eligible to be supported (although outreach support would still be available to victims accommodated by the council).

The following sections provide guidance on some of the key issues.

Identifying risks and needs

Effective needs and risk assessments are a core part of supporting victims, and of the referral process to the NRM. Both initial assessments and ongoing multi-agency assessments will help to ensure that potential victims are linked into the correct services, and that multi-agency provision is coordinated and available at the right time.

Initial needs and risk assessments

When an individual is identified as a victim of modern slavery, an initial urgent needs and risk assessment should be undertaken to understand what steps are needed to get potential victims out of immediate danger. Who does this will depend on an individual council’s (and wider local area) referral pathway and how they have first been identified. As per the previous section, homelessness/housing services should be clear on the steps to be taken in the event that a victim is identified within the service as well as where a victim has been identified outside of the service but will need to be referred into it for consideration of housing need.

The Human Trafficking Foundation identifies three immediate questions which this first assessment should cover based on the victim’s immediate safety, as well as a series of follow up questions related to their basic needs:

- Is the potential victim still being or likely to be targeted by their trafficker?

- Are they still in or near the location where they were exploited? Does their attacker have access to their location?

- Do they need to be moved from their location as soon as possible?

- Are there any child protection risks?

- Are they housed?

- Do they have income, food, and warm clothes?

- Are there any immediate risks to physical and mental health?

If immediate risks are identified, including risks from staying in the immediate area, then homelessness services should be prepared to try and identify emergency accommodation for any eligible potential victims, potentially out of area.

If immediate risks are identified and cannot be immediately met, then an expedited referral to the NRM can be considered. To increase chances of the referral being successful, it is important to write on the referral that it has been made in haste, that only the basic information needed to identify individuals as potential victims has been included, and that further information will be provided at a later stage. Failure to provide this further information could however lead to a negative reasonable grounds decision being made.

At this stage, the lead officer can also contact The Salvation Army and make them aware of the new potential victim. This will help The Salvation Army to prepare their services in the event that potential victims are referred into the NRM.

In-depth needs and risk assessments

If the potential victim is not considered to be at immediate risk, then a more in-depth needs and risk assessment should be undertaken.

This assessment should consider the following in relation to housing:

- Does the potential victim have somewhere to stay until a referral can be made into the NRM and they receive a reasonable grounds decision?

- Are they eligible for assistance under the 1996 Housing Act?

- Are they likely to be considered priority need, and therefore potentially owed a duty to provide interim accommodation?

- If the person is not eligible, are there non-statutory options where they can be housed? Would The Salvation Army or sub-contracted housing provider consider accommodating them before the reasonable grounds decision is made?

- Are they at risk of future homelessness due to any financial difficulties or debts? This might include debts which have been made in their name by their exploiter.

There are also a series of wider issues that may be considered as part of this process:

- Are there any needs or risks relating to safety or health, eg risk from exploiters, physical or mental health issues, risk of self-harm or suicide, substance misuse issues and treatment plans that need to be shared by drug and alcohol teams, risk of absconding from accommodation, risk of re-exploitation?

- What support needs to be in place in interim accommodation to mitigate these risks?

- Does the potential victim need any professional legal advice to support them with welfare benefit claims, immigration or asylum issues, criminal law advice, housing advice, or accessing victim compensation? Are they entitled to free advice for anything covered by legal aid?

- Do potential victims need to be referred into asylum? Councils should note that this might not always be appropriate, and that councils cannot legally provide immigration and asylum advice. Instead, referrals should be made to immigration advisers or lawyers who are registered with the Office of the Immigration Services Commissioner.

Intersection with NRM referral process

After an individual’s case has been assessed for indicators of modern slavery and any immediate safeguarding risks dealt with, a referral into the NRM should be discussed with the individual. Again, the internal referral pathway should make clear who is responsible for discussing this with them and taking it forward in accordance with their wishes; responsibility may rest with a frontline service team such as homelessness/housing, or it may sit with a modern slavery coordinator or safeguarding team.

The potential victim’s explicit, informed consent is needed for an NRM referral. This means that they should understand:

- what the NRM is

- what support is available through the NRM

- what the possible outcomes from referral are

- where their details will be sent

- that they can choose to enter or leave NRM support at any time.

The West Midlands Anti-Slavery Network has produced a guide to the NRM for first responders to share with victims, which is available in a number of different languages.

Where there are concerns that individuals might not have the capacity to consent, appropriate safeguarding procedures should be followed with decisions made in the best interests of the potential victim.

It may be helpful for non-British nationals to have legal advice about entering the NRM; while this is not currently within the scope of legal aid, it may be possible be able to access this as part of advice on claiming asylum, or from a law project or pro-bono offer.

Where victims do consent, an NRM form should be completed. The Home Office has published guidance on completing an NRM form while the Scottish Government has produced a short toolkit on making an NRM referral. An SCA presentation on NRM referrals from a recent LGA webinar is available online.

It is crucial that referrals include enough information as is useful to identify people as potential victims. Even where responsibility for submitting an NRM referral rests elsewhere, homelessness/housing services already working with potential victims should consider providing input into the form as part of local multi-agency risk assessment or other processes.

Some victims of modern slavery will not be willing to be referred into the NRM; for example, they might not consider themselves to have been exploited, may distrust authorities, or not consider a referral to be in their interest. The council is still subject to a duty to notify the Home Office that they encountered a potential victim.

In these circumstances, councils can still consider:

- whether they owe potential victims homelessness duties

- whether they can make a referral to a non-statutory accommodation provider or safehouse

- whether they have legal powers to accommodate victims in order to protect them from further re-exploitation, if that is possible.

The council and its partners should ensure that there are opportunities for potential victims to consent to referrals later, as people might change their mind over time and as they build trust in their support workers. Evidence from the TILI report shows that where people were not referred into the NRM, their housing situation was significantly worse than people who had agreed to enter the NRM. This is because the organisations that supported them did not necessarily have the specialist knowledge and resources of organisations within the NRM.

Accommodating potential victims and victims of modern slavery

Emergency/temporary accommodation

As highlighted earlier, the provision of accommodation after a victim has been identified but prior to them moving into NRM accommodation (if they do so) has been a consistent challenge. The Government had previously committed to ‘places of safety’ provision to cover this period, but in practice this has been limited only to victims rescued from their exploitation. In practice, it may take several days before a reasonable grounds decision is received and an individual can enter the NRM, and during this time, they may be unhoused and in need of emergency accommodation. Local housing authorities should use this time to make enquiries into potential victims’ homelessness or risk of homelessness as part of the needs assessment process set out above, and make placements into emergency accommodation where possible.

Homelessness services should consider the following principles:

- In all cases, councils should ensure they are following their safeguarding procedures. If there is a risk of serious and immediate harm to victims, they should be offered a safe place to stay.

- Decisions on whether potential victims are eligible for statutory homelessness support and interim accommodation will need to be made quickly, to reduce the risk of re-exploitation as much as possible.

- Potential victims of modern slavery may well be in priority need due to vulnerability as a result of exploitation. They are potentially unlikely to have the documentation needed to prove eligibility at short notice.

- Homelessness services participating in multi-agency case conferences can help to speed up decision-making, as key information can be shared in existing forums and with the right decision-makers.

- Regional multi-agency case conferences, which include several local housing authorities, can help to coordinate provision and increase the pool of available emergency housing

- This can also be useful in cases where victims need to be housed outside their local area for safety reasons, as it means that they can access accommodation in other council areas

- However, councils should carefully consider whether it is always appropriate to move potential victims out of area, eg if they are receiving specialist services or support in a particular area. If accommodation is only available out of area, then councils should arrange to share key information with key services in the new area to ensure continuity and reduce the need for victims to retell their story.

- Emergency accommodation should be assessed for suitability and safety. For example, shared accommodation might not always be suitable for potential victims.

- Where potential victims do not have recourse to public funds but want to be referred into the NRM, they could potentially be accommodated by The Salvation Army or other charity. As the NRM housing provider, The Salvation Army is not obliged to accommodate potential victims before they receive a reasonable grounds decision. However, they might agree to provide this accommodation if potential victims are in urgent need or destitute.

Councils may also need to go through this process if an individual receives a negative reasonable grounds decision, including considering:

- whether they owe individuals assistance under the Housing Act

- whether they can make a referral to a non-statutory accommodation provider

- whether housing assistance is owed under child protection duties.

Housing and support during the NRM process

If potential victims receive a positive reasonable grounds decision, then they become entitled to at least 45 days of VCC support during a “recovery and reflection” period. This support might include access to relevant legal advice, practical help, and emotional support. It can also include access to safehouse accommodation; however, the Homelessness Code of Guidance states that:

‘Where a potential victim is already in suitable accommodation, such as accommodation secured by the local authority or asylum accommodation, and there is no risk to them in remaining at their current location, they will usually continue to remain in that accommodation unless a [victim care contract] needs-based assessment reveals a specific need for [victim care contract] accommodation.’

Councils should not assume that individuals referred into the NRM will always enter VCC accommodation, but instead work on the basis that if the council owes a victim a duty, the usual expectation will be that the council should continue to house that individual while they are in the NRM. The section below outlines considerations for councils in relation to long term housing support for victims.

Where potential victims do enter victim care contract accommodation, there are a number of issues that homelessness/housing teams (along with other council services and multi-agency partners) may need to clarify regarding support for the victim and their long term plans on coming out of the NRM. One concern councils have often raised is that when individuals enter the NRM, they receive no further updates on their progress or needs. With an increasing focus on supporting individuals out of the NRM and into mainstream services, and strengthening relationships between VCC organisations and statutory services, it is hoped that better information sharing will develop.

Homelessness/housing teams from the council or area where a victim was referred could consider the following at an early stage:

- If potential victims already have accommodation in place but it has been agreed they will enter NRM accommodation, councils should liaise with the DWP and ensure that benefits/rent continue to be paid during the individual’s stay in NRM accommodation, so the individual’s tenancy is not disrupted.

- What communication, if any, needs to take place with the accommodation provider? Will someone within the council maintain communication with the potential victim’s safe house, so that they are aware of the victim’s NRM exit plan and housing needs?

- If the potential victim was moved to a different local area, which council will handle their case once they leave NRM accommodation? Victims may choose to return to their old place of residence if they have links with that region - housing services and other local agencies should make sure they should consider what provisions they can make. The council where the potential victim was first identified should ensure that they carry out the necessary local connection assessments as soon as possible so that there is clarity about the victim’s entitlement.

Wider council services and multi-agency arrangements could also consider the following, issues, in conjunction with the VCC contractors. MARAC style arrangements to support victims will help facilitate joined up discussions about a support plan for a victim:

- What multi-agency support will need to be in place for potential victims who are either staying in the council area, or likely to return after leaving NRM accommodation?

- This should consider safety, healthcare and substance misuse treatment, legal and immigration advice, potential employment, practical, cultural and psychological needs and any dependants (including children).

- It should also consider the likelihood of re-trafficking, as this is a significant risk for many victims of slavery after they escape exploitation.

- What flexibilities can be put in place to enable victims to access the necessary mental health or substance misuse support?

- If a potential victim does not meet the Care Act criteria for support, could referrals be made to specialist charities?

- How quickly can plans be formulated and delivered?

- Assessment processes around housing and other services may need to be fast-tracked, as there is a high risk of re-exploitation once people leave victim care contract accommodation. Local services should work with the VCC to discuss when services can be made available and how these will work in conjunction with ongoing VCC support.

Longer term housing solutions and support

Having access to safe and stable accommodation is an important part the recovery process for victims, and vital for reducing the risk of re-exploitation. Council homelessness/housing services have a key role in facilitating this, for example. through local schemes to help victims access the private rented sector or commissioned supported housing.

Depending on the circumstances of an individual case, councils may need to consider this before, during or after a victim is supported through the VCC.

For victims in VCC accommodation, after a positive conclusive grounds decision they will receive at least 45 days of further support within the VCC; a recovery needs assessment will be undertaken to identify an individual’s tailored support needs. Part of this process will be to identify how to transition victims into longer term accommodation and support, and should involve close working between VCC organisations, councils and other organisations.

At this stage, if they haven’t done already (for example, because the case is new to their area), councils will need to consider whether a victim is owed any or all of the main homelessness duty, the prevention duty, or the duty to provide interim accommodation and respond accordingly.

If potential victims receive a negative conclusive grounds decision, they have nine days to leave victim care contract accommodation. This can leave individuals with a very short amount of time to source alternative accommodation and support; again, close engagement between the VCC provider, relevant council and other partners is advised.

Councils’ homelessness teams in particular should consider the following:

- If potential victims are foreign nationals who have received a positive conclusive grounds decision, and have been granted leave to remain with recourse to public funds, then they are likely to have recourse to housing assistance under the Housing Act.

- If the council can’t provide assistance, then they could support individuals to take immigration advice. They should also consider whether victims are able to access asylum accommodation.

- If only shared housing is available, councils should ensure that this is suitable.

- Victims might have developed a connection to the area that is local to their safehouse accommodation – can councils apply flexibilities around local connection?

Beyond housing, NRM exit planning between the VCC provider, council and other partners should also consider ongoing support to the victim around a range of different aspects of their support plan such as benefits, immigration, healthcare, and social care support. This could include making provisions for the following:

- legal advice on immigration, including applying for right to remain if needed

- registering with a GP

- exploring access to education, volunteering and employment

- accessing classes to improve English language skills

- obtaining a national insurance number

- accessing benefits

- accessing non-statutory support, including from specialist third sector organisations.

In all cases, if people do not meet the criteria for statutory support, councils should consider referrals to the non-statutory sector.

Case studies

Checklist for homelessness/housing service leads

Have you:

- Identified your council’s modern slavery coordinator or lead team and made links with them to discuss the issue?

- Clarified your council’s internal referral pathway for modern slavery and what you should do when homelessness/housing identify a suspected victim?

- Reviewed your team’s policies and procedures (eg for assessment, placement etc) to ensure they take into account the specific needs of victims of modern slavery, including potential local connection issues?

- Assessed what emergency accommodation is available locally to draw on when a victim is identified/pre-NRM?