A place shaping approach recognises the council’s role goes beyond the delivery of services. It is the only local organisation with a mandate to act as a democratically-elected arbiter of place.

Councils, culture and place shaping

Place shaping is a term coined by Michael Lyons in the Lyons Inquiry (2004-7) into the form, function and funding of local government in England. Lyons suggested that local government should act as the voice of a whole community and as "an agent of place".

A place shaping approach recognises the council’s role goes beyond the delivery of services. It is the only local organisation with a mandate to act as a democratically elected arbiter of place. It holds the responsibility to represent a diversity of local communities and to mediate between different voices to build and shape local identity.

Nowhere is this place shaping role more relevant than in culture. People tend to think of the council primarily as a funder and operator of cultural services, and this is certainly an important part of their work, but councils also have other roles to play in shaping the cultural offer within a place.

With increasing pressure on public funds, not only will local government need to find solutions to sustain its existing cultural infrastructure and programmes in communities, its role will increasingly focus on brokering partnerships to facilitate cultural development and build capacity in the sector.

Strategic plans for culture which are locally rooted, jointly owned with local communities and stakeholders and collectively resourced with government, arms-length bodies, funders, private sector businesses and the charitable sector will help to develop evidence-based, long-term approaches of significant scale that are able to deliver positive change for our places.

The cultural eco-system

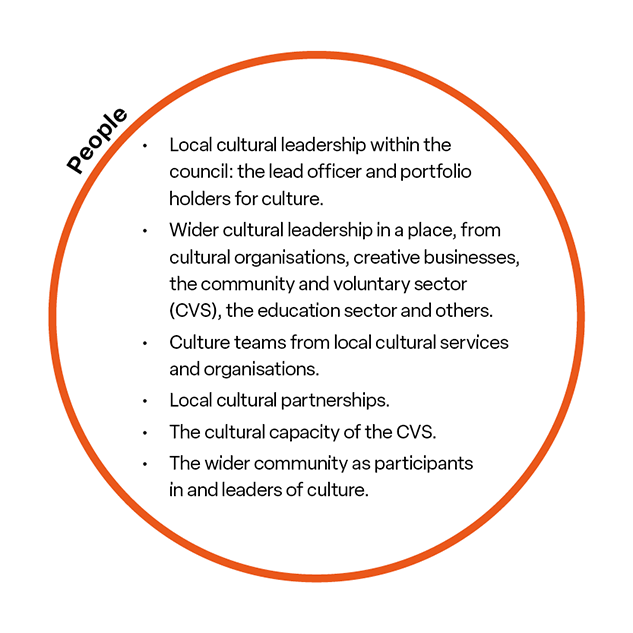

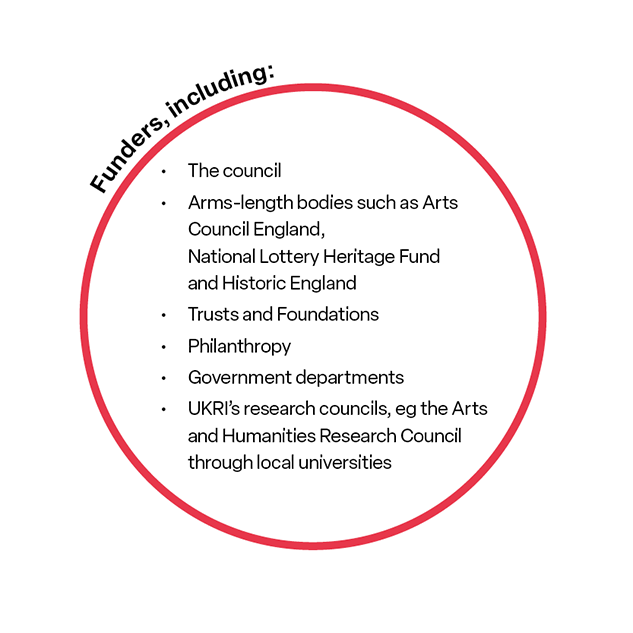

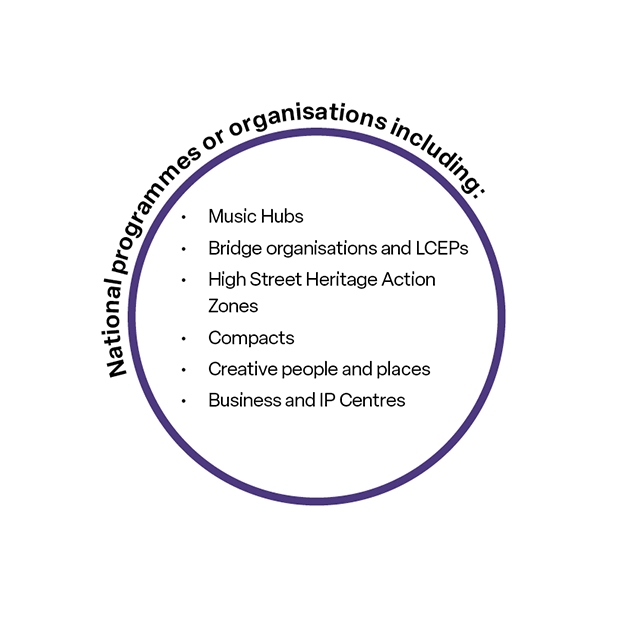

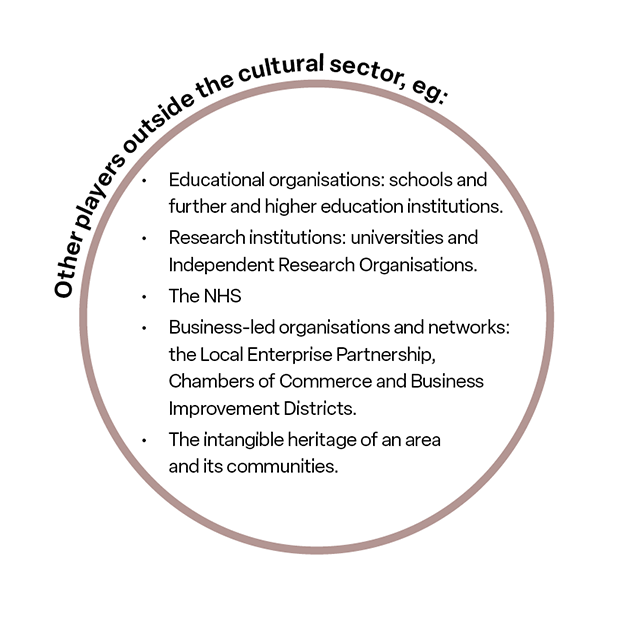

Local cultural infrastructure is highly complex and differs greatly from one place to another. This section highlights some of the organisations and factors that contribute to the cultural ecology of a place.

“Culture should be seen as not only the commissioning of arts and the production of events, but also as a tool; that builds upon the heritage of the area; that builds a shared vision and identity for the area that is steeped in history and has a wealth of cultural assets; that builds the local economy particularly in the context of tourism and creative industries; that improves the local quality of life and encourages engagement in community activities; and that provides new ways of tackling challenges around health and well-being.”

- Cultural Strategy in a box (LGA 2020)

The Commission received over 50 case study submissions from local cultural services and organisations, demonstrating how councils and their cultural partner organisations and practitioners were delivering better places for local residents.

The case studies highlight a number of key indicators for a council in supporting the success of a place-led strategy for culture.

- Clear vision and leadership: A local leader or mayor who “gets” culture is very important to making change.

- Resourceful lead officers for culture: Council lead officers for culture have an enormous collective knowledge base covering strategic and operational delivery of culture. They play a vital role in delivering local services, engaging with the sector to shape a strategy, coordinating funding bids to resource its delivery and advocating for culture across the council and its wider partners in an area.

- A good understanding of local assets: both physical and intangible and a holistic view of how they relate to one another. While the funding and delivery of services is an important aspect of a cultural ecosystem, it is much wider than this. Successful strategies for place increasingly include an understanding of the area’s historic environment and the heritage of an area and its communities, as well as other significant assets such as visitor attractions and local further education and higher education provision.

- Familiarity with the funding options available for delivering a strategy.

- Early engagement of a wide range of stakeholders including cultural organisations, the Voluntary and Community Sector (VCS), the business community, and public sector leadership

- Active collaboration and coproduction with communities to build a shared and inclusive vision for place.

- Cross-council political and officer involvement and commitment (for example, economic development, public health and children’s services, parks and open spaces).

- Leadership from the creative industries as well as publicly-funded arts and culture.

- An evidence-based cultural strategy with clear success criteria, plans for evaluating programmes of work and a clear approach to data informed decision making.

Some of the principles of success highlighted across the case study examples included the following.

- Access is not a fixed point. Access needs are constantly evolving and councils have a key role to play in keeping on top of this to ensure the local cultural offer remains inclusive to all.

- Cloning doesn’t work: A local and specific approach which draws on the unique culture and heritage of place makes a local strategy authentic to place, gives local communities buy-in and drives a successful visitor economy where uniqueness is of significant value.

- Success breeds success: Some ‘quick wins’ can help to get a longer term approach off the ground. Trust between stakeholders is vital, but is best built through delivery.

Culture and place is a significant theme in the work of the main cultural arms-length-bodies, all of which have committed to developing collaborative place-led models of working:

- Arts Council England, in its ten-year strategy Let’s Create says, ‘Culture and the experiences it offers can have a deep and lasting effect on places and the people who live in them. Investment in cultural activities and in arts organisations, museums and libraries helps improve lives, regenerate neighbourhoods, support local economies, attract visitors and bring people together.’ Research for ACE found that culture influences where people choose to live, and what they think about their area.

- The NLHF says that “Heritage sits at the heart of a place’s identity, adding depth, character and value” and that it connects “people and communities to a place and boosts local economic prosperity.” The “Heritage and place” report commissioned by NLHF shows how it can maximise its investment and impact through a place-based approach, and that shared data and intelligence, strong partnerships, and a fit with a broader vision for the area are keys to success.

- Historic England supports place-making working with communities and planning authorities – the range of tools and interventions it uses is described in “Support for place-making and design”. In its Places strategy (2018), Historic England says heritage is the “glue” for place-making, and that its aim is to see places revitalised with heritage at the heart.

-

The consensus around the importance of place-led models is significant. There is an opportunity for the arms-length bodies and councils to work together to build on these models, as we set out in the recommendations.

A Day in the Life…of a culture officer in a council

At a very basic level, officers are the professional, specialist resource for culture in their authority. While some councils have teams of officers with specific areas of expertise, for example in public art, creative industries development or arts and regeneration, most have very limited capacity. Sometimes one part-time officer might cover all these roles.

So what does a typical day look like? Well, there’s nothing typical about it!

An officer in a more operational role could be programming and running a small venue, completing a risk assessment, or delivering a community arts project they’ve raised the funds for. They could write a speech (say for the opening of an exhibition in the library) or support a councillor at a meeting with a special interest group. They might be running workshops to coach cultural organisations toward stronger funding bids, better governance or improved impact assessment. Cultural officers are natural multi-taskers.

Hopping between councillor case-work, a workshop on neighbourhood priorities, a panel to determine a public art commission, meeting an artist about a project at development stage, lobbying internally for a cultural organisation to be granted rate relief, discussing an upcoming tourism campaign or reviewing business plans of a funded company alongside their Arts Council counterpart could all be part of the day.

At a senior level, officers might be part of a discussion with politicians or policy colleagues on over-arching council plans, or offer advice on the impact of council budget proposals on statutory obligations or vulnerable groups. They might provide suggestions for alternative approaches or good practice from other areas. They could be writing business cases for government investment programmes, supporting a portfolio holder as they present at cabinet or representing the council at a regional or national meeting. Increasingly, they might also be responsible for other services, with a different cast of key characters and policy priorities, all demanding attention.

The work of cultural officers is heavily dependent on the scale and nature of their organisation; a council is a hugely diverse organisation, with complex stakeholder management demands and onerous corporate processes.

While every day is different, they all require a strong working relationship with councillors, a good grasp of related policy areas, an extended network of contacts inside and outside the council, solid technical knowledge, an understanding of local communities’ assets and needs, and above all, a highly developed belief in the power of culture to improve lives."

- Val Birchall, Chief Cultural and Leisure Officers Association

Kirklees: Weaving together the fabric of place

The first WOVEN Innovation in Textiles Festival in June 2019 was conceived to celebrate the district’s globally recognised industry and its inspiring past, present and future. Practically the festival was a textiles showcase through 100 events across 50 locations in towns, villages and hamlets of this diverse district. It encouraged exploration of proud industrial and social heritage, hands on creativity, recent innovations and future opportunities for careers and creative thinking. Strategically the project was more complex, aiming to strengthen Kirklees’ unique identity, bringing four distinct sectors together: the council, the textile industry, education (Huddersfield University, schools and further education colleges) and the cultural sector.

By bringing diverse partners together, the programme grew organically. A shared passion led to a shared vision and collective understanding, with a realisation of how important textiles are to many people, for many different reasons. 62 per cent of festival audiences said their experience had made them more proud of living in Kirklees and 81 per cent of audiences agreed that the festival has shown them that textiles is a modern-day industry. WOVEN tackled the perception that the textiles industry is past history, demonstrating that it is all about building on the past to inspire tomorrow’s innovation and creativity. The programme promoted new employment opportunities through careers events, schools programmes and teacher training. It highlighted the industry’s sustainability practices and environmental impact, and showcased developments that are radically changing textile manufacture, as well as challenging our relationship with fast fashion.

This first WOVEN festival was a pilot, funded by Kirklees Council, providing the foundations for this now biennial festival. It’s the start of an exciting journey, to make this a festival of local, regional, national – and perhaps even international – significance. The impact of textiles in Kirklees does not stop there. The textile industry’s historic investment in music involved the development of brass bands and orchestras, immigrant communities coming to work in the mills, bringing with them new sounds. The cultural reach and impact go far beyond the walls of any mill or manufacturer, resulting in a strong and vibrant music ecology.

Abby's story

Abby: Arts Council England Youth Advisory Board Member, Scunthorpe

“My grandma liked art. We used to do arts and crafts together and she took me to the 2021 Gallery and North Lincolnshire Museum, which is where I got my interest in fossils. The gallery had little exhibitions and a kids table with activities I really enjoyed.”

Abby is 19 and lives in Scunthorpe. She has a strong bond with the town, which her family have lived in for generations. Abby hopes to have a career as an artist and creative producer in her local area. However, Abby is the only person from her art foundation course who has not left the area and she says that being from Scunthorpe is the biggest obstacle to her career.

“We’ve been downtrodden for so long, no one has any hope. It’s very grey and dreary and we have poor air quality from the steelworks. I have found painting and drawing makes me much happier and it makes me see the possibilities in Scunthorpe.”

Abby joined Arts Council England Youth Advisory Board in 2021 with the aim of advocating for greater investment in North Lincolnshire.

“There are activities for children and adults, but there’s a gap of 10 years with nothing focused on young people. It’s frustrating because without opportunities you are forced to move away or get a different job.”

Despite this, Abby sees that things are starting to happen in Scunthorpe. While studying at sixth-form college she responded to an advert to be a youth adviser to the Festival of Creativity, a project funded by North Lincolnshire Council and Arts Council England.

Through this she found out about a local maker fair and started to build her network of local makers and artists. She is now part of The Crosby Collective, a community makerspace funded by the Big Lottery Fund and Community Led Local Development (CLLD) Fund.

“The Crosby Collective is a foot in the door. There are photographers, designers and they’re all willing to talk to you. It’s hard to get into arts and culture if you don’t know the right people.”

Over the summer of 2022 Abby worked at the Fountain Arts summer school, offering workshops to young creatives aged 12-14 as part of North Lincolnshire County Council’s Holiday Activities Fund (HAF) programme. She has recently been selected as an artist exhibitor at a local café and art gallery and is taking part in a trainee producer programme funded by North Lincolnshire County Council. Abby hopes to start an event of her own in Scunthorpe.

“Without public funding the gallery wouldn’t be there, the museum wouldn’t be there. Crosby Collective wouldn’t be there and there would be no places to go. It would be a ghost town. There’s still work here, but just having work and nothing else isn’t a good quality of life.”

“Cultural identity is strongly tied in with a person’s sense of engagement, belonging, understanding and appreciation of their ‘place’. Placemaking capitalises on a community’s unique assets, inspiration and potential with the intention of creating public spaces, places, events and activities that promote people’s health, happiness and wellbeing.”

People, Culture, Place: the role of culture in place making (LGA and CLOA 2017)