The independent Commission on Culture and Local Government was set up by the LGA’s cross-party Culture, Tourism and Sport Board to bring national, regional and local actors in the local publicly funded cultural realm together.

Forewords

Baroness Lola Young of Hornsey, Chair

This Commission was set up in early 2022 to investigate the role of local publicly funded culture in supporting our recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic. The context in which we are publishing is very different and with so many serious challenges facing communities it might be easy to ask why we are focused on culture. But in my view, this has never been more important.

2023 marks the 75th anniversary of council spending on the arts. It is right that we celebrate the role councils plays in binding together culture, communities and place - and discuss what publicly funded culture needs in the next 75 years. Our report sets out the issues and also our ambitions for more resilient, diverse, inclusive and place-led approaches to culture.

The pandemic was a powerful reminder that people reach for culture in times of crisis, as well of those of joy and celebration. Access to culture and creativity provides hope and inspiration and enriches people’s lives. That access must be fair for all.

The Commission heard about the many and varied ways local culture contributes to places. A vibrant cultural ecosystem creates jobs, supports health and wellbeing, enhances learning and opens up opportunities for young people. It draws people to the high street, underpins the visitor and night-time economies, supports the growing creative industries and helps to make places unique.

Cllr Gerald Vernon-Jackson, Chair of the LGA Culture, Tourism and Sport Board

When we started this Commission, there was no war in Ukraine, inflation was below 2 per cent, and both food and energy prices were quite low. Much has changed since then, and with an expected in-year deficit in council budgets of around £2.4 billion, we will have to make difficult choices about what and how we deliver in the future.

The findings of the Commission and the case studies alongside it show that councils have quietly been working with their cultural partners to deliver brilliant work against every outcome you can imagine – economic growth, boosting wellbeing, improving pride in place, and supporting the talent and skills of the next generation. This isn’t exploratory work but a proven way of ensuring our country will thrive economically and be a great place to live in the future.

What will need to change, as shown in this report, is the way in which we collaborate to do it – no single organisation now has the funding, staff time or skills to do this alone. So councils, cultural organisations, and our partners in central government will need to keeping working together to support each place to be the most vibrant, best place it can possibly be. That means pooled and aligned funding streams, open and transparent conversations with communities about what they need, and a shared vision that everyone works towards. We can do it!

And we have done it. In the years after World War II, in a time more difficult than now, the Government decided that then was the right time to invest in culture. They set up the Arts Council. What’s more, they appointed an economist as to run it – none other than John Maynard Keynes – reporting not to a cultural department but the Treasury itself. In a time of adversity, this investment showed faith that culture is a fundamental part of creating better times ahead.

I’d like to thank all the Commissioners for the incredible work that has gone into developing this report, and to everyone who has supported it with their expert insight, practical experiences, and enthusiasm. In particular, Baroness Lola Young for her brilliant chairing of the Commission, and Councillor Peter Golds, who ably represented the LGA’s Culture, Tourism and Sport Board. The findings of this report will direct the LGA’s work for years to come.

Charlotte Patterson and Rawan Yousif - Arts Council England Youth Advisory Board

We are a part of Arts Council England’s Youth Advisory Board. The board is comprised of 18 young people from across the North of England, advising on a range of policy topics that supports their strategy Let’s Create. During the summer, The Local Government Association, consulted with us on our experiences and perceptions of local culture. Our views have been featured in some of the recommendations including Creative Learning and Pathways to Creative Employment; Health and Wellbeing; Access and Leadership & Power.

It is a necessity to have cultural opportunities available to young people in their local area if inclusion is a priority for both Government and leading cultural organisations. You cannot achieve inclusion without improving access to culture; making access convenient, affordable and enjoyable. If high-quality cultural offerings are available to young people in their local area, this can remove barriers such as travel costs, which can be a major obstacle for young people, particularly those in rural areas. Furthermore, if facilities in smaller, regional venues for young people with disabilities can be improved, this would help put cultural experiences in safe, familiar and convenient places within reach.

Improving access to culture will increase inclusion and, in turn, representation, as we will see a wider variety of people able to access the arts and encouraged to begin fruitful careers in the cultural sector. Better representation will draw more young people to cultural venues and hubs, seeing themselves represented on stages and in galleries, and helping them to feel welcome in their local cultural community.

There are additional benefits to improving local cultural opportunities, such as improved physical and mental health. Many board members shared that their sense of identity was strongly tied to their creativity and artistic practice, and they felt their mental health was better when they were able to explore this creativity. As we are still reeling from the effects of the pandemic and multiple lockdowns, many have turned to artistic pursuits as a means of reforming their communities. Connecting with one another through arts and culture, we are able to use shared passions to deal with the serious emotional toll of the past few years. It’s clear to us that arts and culture have a significant therapeutic role to support recovery post pandemic, but these health benefits to individuals and communities surely warrant ongoing investment on both a national and local basis.

We welcome this report to support our demand for cultural offerings in our hometowns and local highstreets. We feel there should be greater onus on inclusivity and access, empowering young people to participate in the arts; not just as audiences, but as creatives and gaining expertise through experience. We ask the creative sector to begin by examining the opportunities they offer and to question whether they are truly accessible. Not only this, but we ask decision makers and others in power, to take the responsibility for opening those doors, to remove those barriers without relying on young people to struggle to break them down.

How we created this report

The independent Commission on Culture and Local Government was set up by the LGA’s cross-party Culture, Tourism and Sport Board. Its aim was to bring national, regional and local actors in the local publicly funded

realm together to communicate the unique role of council funded and supported culture in our recovery from COVID-19; and to set out vision for the future of council funded and supported culture in the context of place.

- eighteen organisations gave oral evidence over the course of four roundtable sessions

- more than 80 organisations were involved in wider focus groups and interviews

- over 50 case studies have been received as written evidence

- sixteen commissioners contributed to the delivery of the report (link to commissioner biographies)

During the Commission’s evidence gathering phase, it also undertook desk research to review existing literature and best practice on the Commission’s four main lines of enquiry. These papers can be found on the Commission’s web pages alongside infographics setting out what it discussed, a case study resource based on the evidence we received and a series of short films highlighting the impact of culture on place.

The Commission was specifically interested in these organisations and services in the context of place, levelling up and recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic. It sought evidence from cultural services and organisations up and down the country to test the following statements:

- Resilient places. Local publicly funded culture can promote civic pride and change perceptions about a place, contributing to improvements in wider social and economic outcomes.

- An inclusive economic recovery. Local publicly funded culture is essential to our national economic recovery, particularly in relation to the growth of the wider commercial creative economy and in levelling up economic inequalities between regions.

- Social mobility. Local publicly funded culture can help to address educational and skills inequalities and challenges around social mobility.

- Health inequalities. Local publicly funded culture can challenge health inequalities exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic.

In doing so, it also investigated what was holding these services and organisations back from delivering more for communities and the local area. What were the barriers and what needed to be changed to allow them to fulfil their potential?

This report explores:

- What is the role of publicly-funded culture in place?

- How can it support locally-led recovery from the pandemic and the cost of living crisis?

- What is the role of the council in supporting this?

- What more can be done to encourage thriving local cultural ecosystems?

How do we define place?

There is no universally agreed definition of ‘place’. The meaning of a place is a perception held by an individual or a group of people and can range from a very specific location like a bench in a public park, all the way up to encompassing a regional identity.

One definition from the National Geographic Society suggests there are three key components of place: location, locale and sense of place. Location is the position of a particular point on the surface of the Earth. Locale is the physical setting for relationships between people. Finally, a sense of place is the emotions someone attaches to an area based on their experiences. Place has been described as the geography over which community is defined. Others will have their own definition which is appropriate to their own circumstances.

From a local government perspective, place would typically refer to council boundaries, but it is worth recognising that there are multiple tiers and types of local government, that most councils have more than one centre and that most people live their lives blissfully unaware of council borders. This is why it is essential to work directly with people when planning and delivering cultural services and activities. By understanding the various definitions of place that exist within a community, services can be most responsive to their needs.

Why is culture important?

Culture, heritage and creativity are essential to our future national prosperity and wellbeing.

During the pandemic, people turned to culture for solace and connection. There was a vital place-based dimension to this. Local cultural services such as libraries, museums, theatres and arts centres reached out to communities in lockdown to address isolation, support mental wellbeing and provide educational opportunity.

As we move towards recovery, we face a whole new set of challenges: a growing cost of living crisis and prospect of recession; pressure on public services; rising inequalities exacerbated by the experience of the last two years; climate change and global instability. Under these circumstances it would be tempting to dismiss investment in cultural services as a luxury we can’t afford.

But for the same reasons, these services have never been more important. Cultural services, organisations and practitioners bring people together at times of crisis and celebration, they provide support and social connection, create jobs, develop new adaptive skills and underpin empathy and critical thinking. In many cases they act as a trusted source of information at a time when the concept of truth is under question.

Besides their unique intrinsic value, they also deliver against many wider challenges we face as a society. Culture, heritage and creativity help to:

- Build resilient, adaptive, networked communities in place, supporting civic pride and revitalizing town centres.

- Promote local economic growth, supporting levelling up through the development of creative clusters, an experiential offer on high streets and providing a foundation for the wider visitor and night-time economies.

- Develop creative thinking, build cultural capital and provide local economies with high quality jobs that are resistant to automation.

- Support better health and wellbeing, particularly addressing challenges of loneliness, isolation and mental ill health arising from the pandemic.

A strong local cultural offer improves quality of life and supports the health and wellbeing of communities, it enhances learning, builds cultural capital and opens up opportunities for young people who might otherwise not experience cultural participation. It draws people to the high street and enhances the visitor and night-time economies, underpins growth in the burgeoning creative industries, supports our international reputation and helps to make the unique and fascinating places that are so fundamental to our country.

But local culture is more than the sum of the outcomes it helps to support. The Commission also found that culture is essential to the identity and aspiration of a place and its people.

This becomes ever more important in the aftermath of a significant shock to society. After the Second World War, culture was encoded in the international response to collaboration and recovery: Article 27 of the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) states that ‘everyone has the right to freely participate in the cultural life of the community, to enjoy the arts and to share in scientific advancement and its benefits'. This right is set out alongside other basic human rights, including access to education, health and housing.

The UK led the way in embracing an approach to recovery that embraced the value of culture, setting up the Arts Council in 1946. The council's first chairman was economist John Maynard Keynes, who used his influence in government to secure a high level of funding despite Britain's poor finances following the war.

Although this was a very different Arts Council from the one we know today, the gesture is symbolic and significant. The acknowledgement that the public funding of culture would be important to a national recovery based around increased opportunity for all was reflected across society: crucially, local government authorised spending on the arts for the first time in 1948. As we face a new set of challenges as a society, we have an opportunity once again to put culture at the centre of our plans for recovery.

We need people and communities who can respond with creativity and innovation to the social, economic and environmental challenges and opportunities facing us. We need places that are able to draw on their unique local heritage to develop resilient and inclusive futures. We need new diverse voices to help us bring fresh thinking to the table.

Quite simply, culture is fundamental to the fabric of our civil society. The picture of Britain without it is a grim one.

How is local culture supported and what is the role of the council?

This cultural infrastructure does not exist without support. Its continued existence relies on a network of funding and support from a mix that includes national and local government, arms-length bodies, foundations and trusts, civil society organisations, volunteers and the private sector, among others.

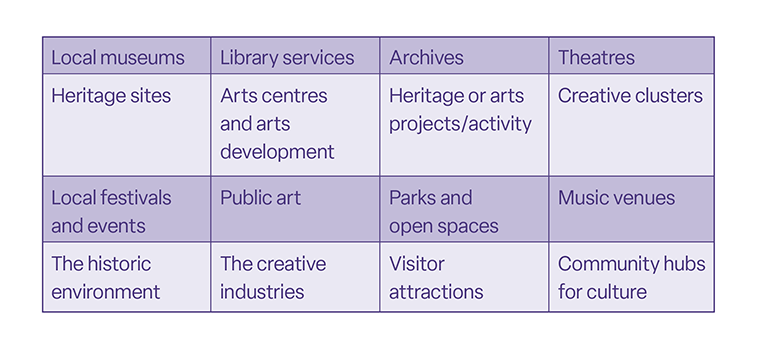

Councils sit at the heart of this picture. They run a nationwide network of local cultural organisations, which in England includes 3,000 libraries, 350 museums, 116 theatres and numerous castles, amusement parks, monuments, historic buildings, parks and heritage sites. This core funding keeps the civic infrastructure of culture running within places.

For councils, cultural spend is a small part of their wider offer, which is increasingly dominated by the rising cost of social care, alongside the many other vital services delivered by local authorities.

But although culture is a small part of what a council does, they remain the biggest public funders of culture nationally, spending £2.4 billion a year in England alone on culture and related services.

The erosion of this support would have a significant impact on our cultural offer as a nation. Publicly funded culture at a local level underpins a much wider cultural ecosystem, including supporting growth in the commercial creative industries and underpinning visitor economies as we explore in the inclusive economic recovery section.

Local cultural services seldom draw the same levels of national media and political attention as national cultural institutions and industries, but they are of vital importance to local communities and provide the foundation on which our national culture is built.

Pressures on culture

Cultural services are still important to communities, but they are facing significant challenges. Increasing pressure on public spending and rising demand for statutory services like social care, meant that council’s net spend on culture and heritage decreased by 35.5 per cent between 2009/10 and 2019/20, while spend on libraries decreased by 43.5 per cent.

The pandemic and subsequent cost of living crisis has only served to exacerbate these pressures. The pandemic saw a sharp drop in income generation by cultural services and organisations across the board. The UK’s arts and entertainments sector was one of the worst hit parts in the pandemic, according to the Office for National Statistics. While for many the Culture Recovery Fund and wider support packages for councils plugged immediate gaps and income projections were beginning to recover, rising inflation and the cost of living has continued to undermine the financial resilience of the cultural sector.

Councils have also been hard hit by the cost of inflation. Alongside increases to the National Living Wage and higher energy costs, inflation has added at least £2.4 billion in extra costs onto the budgets councils set in March 2022. Local government facing a funding gap of £3.4 billion in 2023/24 and £4.5 billion in 2024/25; poses a major risk to cultural services.

Besides decreases in core funding, there has been a rise in the amount of funding allocated through bidding process or ringfenced grants. While councils welcome additional funding for culture, bidding for and administering these types of funds is energy intensive and requires a certain level of local capacity. This can constrain council’s ability to be flexible with their money and achieve better outcomes at a local level, as well as increasing the proportion of the money that must be spent on administrative costs.

Working together

The funding environment is becoming more complicated, but there is still funding spent on culture at a local level. In the context of these pressures on cultural funding, it becomes even more important to spend it well.

- Councils remain significant funders, spending just under £1.1 billion a year in England on cultural services like arts centres, museums, heritage, libraries and theatres, and £1.3 billion on associated services like leisure centres, parks and open spaces.

- Arms-length bodies including Arts Council England (ACE), Historic England, and the National Lottery Heritage Fund (NLHF) remain significant investors in culture across a wide range of programmes and interventions, and each have made commitments to place-based collaboration, providing access to expertise and advice alongside their role as funders.

- The Government has also increased its role as a funder of local culture in recent years, investing approximately £1.57 billion in England through the Culture Recovery Fund and £4.8 billion on the Levelling Up Fund, which identified cultural investment as one of the three ‘themes’ of its first round. The UK Shared Prosperity Fund represents a potential source of investment in local culture, with specific cultural interventions suggested under the ‘Communities and Place’.

- Trusts and foundations continue to play an important role in funding innovation in cultural organisations and enhancing strategic cultural programmes like UK City of Culture.

- The UK Research and Innovation’s (UKRI) research councils and particularly the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) play an important role in supporting high quality research in place. The AHRC awards around £110 million of funding each year to researchers at Higher Education institutions including UK universities and independent research organisations such as the British Library and Tate. Their priorities include the creative economy (they are the main funder of the work of the Creative Industries Policy and Evidence Centre (PEC), cited in this report) and cultural assets.

- International visitors consistently cite the UK’s culture and heritage as primary drivers for their visits, bringing additional wealth to venues and places, and helping to promote our national ‘brand’ on a global stage.

It is becoming ever more important that local, national and regional partners work together effectively in place, to address the fragmentation of cultural funding and ensure the various and important investments add up to a coherent and inclusive strategy for a place.

The Commission found councils sit at the heart of a place and play a vital role in convening, place-shaping, and strategy setting as part of their unique democratic and representative position in the local community. They can balance and moderate different voices in the community. They can bring partners together around a shared vision for a place and connect national funding bodies with the ambition and needs of local communities and organisations. They can also ensure culture is built into other core strategies around health, regeneration, green space, climate change, planning and licensing.

Collaboration with the wider cultural sector, business and enterprise, and national and regional partners is essential if we are to safeguard the services that mean so much to our communities.

Different models of place-based cultural collaborations and partnerships

Opportunities: Policy in flux

We are seeing significant shifts in public policy at this time with opportunities for shaping local cultural delivery.

In the context of this changing policy landscape, there is an opportunity to review how cultural investment works in place, how local, regional and national partners work together to support and invest in local cultural infrastructure and how councils and their partners can best deliver a locally led and agreed vision for culture.

Fran's story

Fran Hartley, Treasurer of the voluntary Friends group at Chantry Library

“It’s so much more than books, Chantry Library creates an environment where people can talk to people, where they are given the time of day. People come in say they are fine and you know they are not. People have the trust in staff and volunteers.”

Fran Hartley is Treasurer of the voluntary Friends group at Chantry Library and a regular attender and convener of the 55 alive social club. She has been involved with the library for about fifteen years. Chantry Library is part of Suffolk Libraries, an independent charity which is supported by the county council.

Fran started volunteering at the library when she heard about opportunities to support the Summer Reading Challenge. Through this she got to know the people of the local area.

“I got to know some of the Mums and children, you build up relationships with them.”

The manager brought together a group of interested people, including Fran, to form 55 alive, a weekly meeting aimed at older people with a varied programme of activities. The group gradually evolved from approximately 12 to an average of 30 regular participants.

“One lady from the 55 alive group joined and is there every week. She’d moved to the area and didn’t know anyone. The club turned her life around. Another lady goes to the knitting group, she had just lost her husband and is now starting to get her confidence back. (Chantry Library) has prevented her getting depressed.”

The Friends Group was established when Chantry became independent from the council. Fran was involved in the setting up of this support group. Part of the role of the Friends group is to raise funds and they have enabled the library to undertake a refurbishment and buy equipment.

“The Chantry area has a lot of low income families so we can’t charge the same for events. The families have to be able to access the service”.

Staff from Hawthorn Children's Centre, which is based on the same site as the library will signpost vulnerable families to the range of activities for babies and children, the top up food bank and donated clothes that are available at Chantry library. The library is also a lifeline for people who may feel isolated. There is a men’s mental health group which meets regularly.

“It’s a place you can go and feel comfortable, relaxed and welcomed. You are appreciated and your roles are valued. We pick up on and respond to the needs of the local community.”

Chantry library creates a sense of place and is seen as central to the area. It is becoming increasingly more important to people.

“People who come do feel as if it’s their place. It has become really important to the local community, if we didn’t have Chantry library Chantry would have lost its heart.”