This submission makes the case to Government for a radical reinvestment in local and combined authorities that enables councils to turbo-charge local growth and create preventative public services that save money and improve the lives of some of the most vulnerable in our society.

Introduction

The UK faces a period of challenge and uncertainty, in which the courage to devolve, backed by the resilience and innovation found in communities across the country, will be vital to navigating the challenges ahead.

This submission makes the case to Government for a radical reinvestment in local and combined authorities that enables councils to turbo-charge local growth and create preventative public services that save money and improve the lives of some of the most vulnerable in our society.

The cost-of-living crisis must be tackled, and the country’s financial challenges addressed. However, despite the increase in local government funding in the past three years, the sector has not recovered from a decade of cuts to central Government funding. Devolution to local leaders, backed by sustainable investment is the most efficient and effective way to meet the immediacy of the crisis and secure a path to long term prosperity.

Together we can emerge from this crisis stronger, more productive, and with power properly transferred from Whitehall into hands of those who know and can deliver for their local communities best.

Executive summary

Inflation at 10 per cent is now at its highest level for 40 years. While largely driven by the impact of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on food and energy prices and a global supply crunch following the coronavirus pandemic these international pressures are hitting people and businesses in local communities right across England. Even with the energy support measures put in place by the government, some poorer households will face difficult choices between food and warmth, and smaller businesses that are the economic lifeblood of towns and villages face the prospect of surviving the worst public health emergency of a generation only to be unable to keep the lights on this winter.

The impact of these pressures is made more pronounced by the scarring effect of the pandemic and the low levels of labour productivity experienced by the UK since the financial crisis of 2008. Moreover, despite interventions from successive Governments the tendency towards national programmes designed at the centre has contributed to rising regional imbalances, leading to an overheating Southeast and economic underperformance in the North and Midlands (for example, the Centre for Cities cites figures showing London’s output is two and a half times that of the North East).

Not only has a culture of ‘Whitehall knows best’ led to a mismatch in service provision with local need resulting in poorer outcomes, but it has also created Departmental silos that tend towards a fragmented, piecemeal approach insufficient to deal with truly long-term strategic challenges such as climate change and the transformative impact of artificial intelligence on the manufacturing and knowledge creation industries.

Councils are at the frontline as the economic storm begins to bite, but they will be only too aware of the pressing fiscal context facing the Government. Public sector net debt was £2,107.4 billion at the end of August 2022, a level not seen since the 1960s.

Local leaders understand the Government’s headroom for manoeuvre is likely to be constrained. They are also clear that, despite a recent increase in funding for local government, having shouldered a disproportionate share (some £15 billion) of public sector savings between 2010-2020, any further reductions in real terms funding for local government will have a direct impact on local services people need and have come to expect. Cuts have consequences: for waste collections, libraries, social care for young people and vulnerable adults.

Throughout the pandemic, councils stepped up to protect their communities and keep businesses going. Their resilience and efficiency is matched only by the high levels of trust shown by residents in their councils. Councils are already leading the way in providing support to households and businesses hit hard by the rising cost of living. They will be crucial partners in enabling the transition towards a more productive and efficient economy, but to do this councils must be sufficiently resourced to deliver.

Measures to contain energy bills are welcome but despite this, without immediate additional funding, councils will face increasingly stark decisions about which services to stop providing as rising costs hit budgets: meaning not just isolated closures of individual facilities but significant cuts to services, including those to the most vulnerable in our society. Despite wanting to protect residents from further cost pressures, council tax rises will be inevitable as councils struggle to plug the gaps in their budgets.

Any cuts to core or grant funding would exacerbate these challenges and service reductions still further.

Based on analysis carried out in May when inflation was expected to be 8 per cent this year, councils need £1.2 billion to manage the impact of inflationary and energy cost pressures, alongside a further £1.2 billion to fund compliance with the national living wage. Since then, inflation has risen to 10 per cent and has been predicted to rise higher. Councils need more funding to meet these pressures. Beyond these short-term pressures, long term sustainable funding is needed to ensure councils have the capacity and capability to deliver an ambitious agenda for residents and businesses. Recruitment challenges and skills shortages are already leading to disruption in vital local services and will escalate further without proper investment in the roles councils need to help serve their communities.

Devolution offers the best value for money and is the right response to fiscal constraints and the ambition for a smaller central state. Given the tools and resources to tailor spending to local needs and opportunities councils will deliver better outcomes than a centralised system characterised by micro-management and duplication. Crucially, place-based approaches such as the Troubled Families programme, demonstrate the value of early intervention and preventative activity.

Government should stay the course on devolution deals, reverse the decision to create an office for local government and continue the process of moving away from piecemeal pots of funding and policy to place-based funding aligned with local needs and opportunities. We believe that the stark fiscal context facing the country strengthens our call for a radical re-investment in local devolution, drawing on the lessons of Total Place and similar programmes to reform public services and better align scarce resources with the needs and aspirations of local communities.

Over the longer term, local government’s placed based leadership is uniquely positioned to invest in sustainable preventative approaches that save money for other parts of the system. No other part of the public sector offers the same scope for unlocking savings in the NHS, the Department for Work and Pensions and the criminal justice systems. Through targeted investment in social care and children’s services, public health and unemployment support we can transform people’s lives and move away from the costly pressures of acute intervention.

Firstly, as set out above, significant new council cost pressures arising from inflation and demographic changes need an urgent response from national government; with further support to address additional costs of £2.4 billion in 2022/23 and funding gaps of £3.4 billion in 2023/24 and £4.5 billion in 2024/25 just to provide services at 2019/20 levels.

In adult social care, the service operates in the context of a decade of underfunding during which a funding gap of £6.5 billion had to be closed. These unstable foundations are being tested further with soaring inflationary pressures associated with the rising cost of living, posing a serious threat to the ability of the service to function at even the most rudimentary level. We are therefore calling for an immediate injection of £6 billion to tackle urgent issues and limit their immediate and short-term impact, as well as further immediate investment of £7 billion to enhance capacity so that councils can deliver the range of statutory duties under the Care Act. We continue to call for reconsideration of the timetable for wider social care reform – both to ease capacity pressures on social care departments, but also to ensure that vital learning from the reform Trailblazer sites is properly factored into the Government’s thinking.

On children’s services, LGA analysis shows that councils spent over £10.5 billion in 2020/21, nearly 25 per cent more than the £8.5 billion spent in 2016/17. Further analysis outlined in our submission to the 2021 Spending Review identified existing unfunded pressures of £1bn each year, with an additional £0.6bn worth of pressures each year to maintain services at the current level of quality and access.

The enormous and increasing scale of the social care challenge facing councils continues to threaten their ability to deliver services and investment for residents. With each year the funding challenge gets harder, impeding local growth, threatening the viability of wider public services and creating poorer outcomes for people. This is an issue that must be addressed as a matter of urgency.

There is also a pressing need to recognise the current pressures facing individuals and families outside the care system but struggling with cost-of-living challenges. The government’s energy support measures have already taken important steps to do so; in this submission we set out steps the government take to strengthen short term crisis support, while our sections on growth and achieving net zero highlight measures that can make a long-term difference to those on the edge of poverty through energy efficiency measures and locally led investment in skills and employment.

Finally, the combination of flooding, heat, drought, ecosystem collapse and global political instability has the potential to create significant damage to the UK’s economy as well as the health and well-being of our communities. Government should support councils to lead place-based approaches to hit net zero targets across housing, transport and energy, leading local green growth which cost three times less than a centralised approach and deliver twice the social and financial returns.

Councils recognise the extreme financial challenges the government, in common with households, and councils, is facing. The necessity of ensuring every pound is efficiently spent and accounted for is understood. But councils have previously accounted for more than their share of funding cuts and cannot absorb current inflationary pressures, nor unplanned funding cuts, without huge harm to local services. The Government must show leadership to support communities and stimulate growth by providing funding to alleviate immediate challenges with long term changes ensuring better value for public money through devolution.

Council cost pressures

At the time of the 2021 Spending Review the LGA estimated that the Government had provided sufficient funding for councils in 2022/23 to meet cost pressures, excluding existing pressures in adult social care, Special Educational Needs and Disability Services, homelessness and other services. Since that time, rising energy prices, increased inflation and the impact of projected increases in the National Living Wage mean that the councils face significant additional costs that could not have been predicted at the time of the 2021 Spending Review.

Councils are facing additional cost pressures of £2.4 billion in 2022/23 since they started to set their budgets in Autumn last year. Fifty percent of these additional costs are due to compliance with recent published estimates by the Low Pay Commission of the National Living Wage, something which local government has no control over. In 2023/24 there is a funding gap of £3.4 billion which rises to a gap of £4.5 billion in 2024/25 just to maintain services at pre-COVID levels.

These figures exclude improvements to services, existing pressures in services and the underfunding of adult social care reforms. They are also based on the forecast for the consumer price index (CPI) in March which was 8 per cent for 2022/23. Inflation figures published since then show that inflation in August 2022 was 9.9 per cent so the figures are already an underestimate.

For all these pressures to be met through council tax alone, income from council tax would have to increase by well over 10 per cent next year which is neither sustainable nor desirable given the current cost of living crisis. Without additional funding to cover these costs, councils would need to making savings equivalent to stopping spending on all cultural and leisure services such as libraries, swimming pools, open spaces, combined with spending on waste collection and Trading Standards.

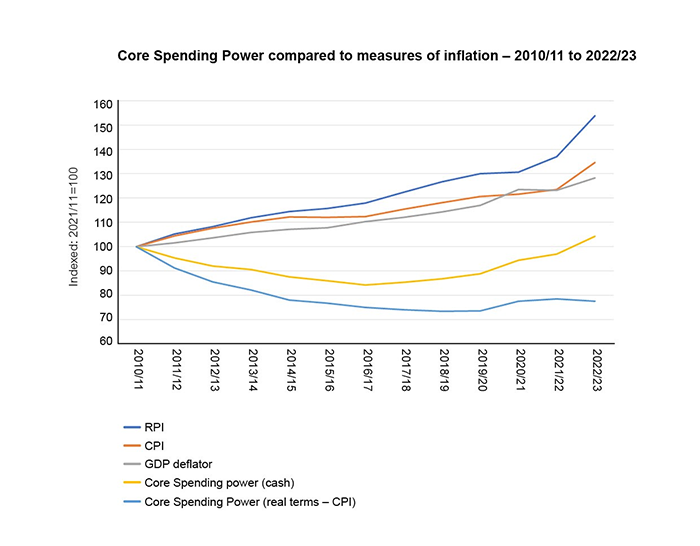

Source: Office for National Statistics Inflation and Price Indices, Department for Levelling Up, Housing, and Communities final local government finance settlements

In a recent survey of local authorities by the LGA, all respondents were facing additional cost pressures which were not included in their budget for 2022-23. In particular, authorities were experiencing additional financial pressure or risk from pay pressures (94 per cent), energy price increases (94 per cent) and contract prices or re-negotiations (88 per cent) to a great or moderate extent. In terms of contracted out services, 42 per cent reported that contracts were being passed back to the council and despite putting plans in place to try to mitigate the pressures in contacted out services, 58 per cent reported there would be a negative impact on service quality and delivery. Respondents had already planned action to meet additional cost pressures; in particular, 91 per cent of them plan to use reserves and 81 per cent are planning efficiency savings or underspends in other areas. However, combining all strategies which respondents provided will only meet 37 per cent of the estimated cost pressures, leaving nearly two thirds of cost pressures still unmet.

The modelling covers revenue costs of councils only. Council capital programmes are also being affected by inflationary and other pressures. Eighty-one per cent of respondents to the LGA survey reported additional pressures or high-likelihood financial risks to their council's capital budget for 2022/23.

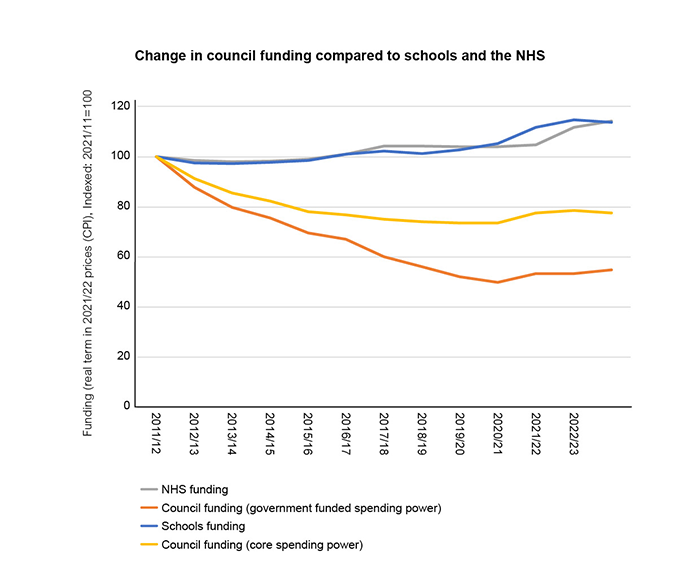

As noted, councils delivered more than their fair share of the burden of putting public finances on a more sustainable footing between 2010 and 2020 compared to other services such as the NHS and schools, with a £15 billion real terms reduction to core government funding over that period.

Sources: Department for Levelling Up, Housing, and Communities final local government finance settlements, Department for Education School Funding Statistics, His Majesty’s Treasury Spending Review documents

Notes:

- Core spending power includes the main streams of government funding to local authorities alongside council tax. The data is produced by DLUHC.

- Government funded spending power is core spending power minus council tax.

- NHS Funding taken from the Departmental Expenditure Limits (DEL) set out in the 2010, 2015, and 2021 spending reviews. Covid specific funding has been removed where relevant.

- Schools funding includes funding for all state funded schools, and covers the Dedicated Schools Grant but excludes early years and post-16 high needs funding.

- All data is deflated to 2022/23 prices using each year's April figure from the CPI September release published by the Office of National Statistics.

The traditional means of delivering efficiencies within local government have been exhausted and there have already been cuts to services.

There is also a persistent myth that all councils should be able to spend at the same level per head of population. However, LGA work undertaken prior to the pandemic showed that the vast majority of remaining variation in spending between councils on older people’s adult social care and children’s services – the two biggest service areas – was explained by factors outside the control of councils (78 per cent and 71 per cent respectively).

To protect all services including those to vulnerable adults and children the costs pressures facing councils need to be met with sufficient funding and long-term funding certainty. Councils are ready to help the Government deliver further significant efficiencies to the public purse through the following measures:

- A renewed focus on prevention, backed by government investment to address existing and future demand for services such as social care, homelessness support and community safety. This would also lead to saving elsewhere in the public sector such as the NHS, employment support and the criminal justice system.

- Reducing the fragmentation of government funding. Research commissioned for the LGA found that in 2017/18, nearly 250 different grants were provided to local government, around a third of which were awarded on a competitive basis. A cost to central and local government that could be avoided.

- Bringing budgets together in a place. The approach to tackling fragmented funding can go much further, by looking beyond just local government funding. We need to allocate money to places and not departmental silos. A shared financial and governance framework will mean that services can better align with local priorities and local duplication of efforts can be eliminated. The fiscal plan should place emphasis on communities and place by introducing multi-department place-based budgets, explicitly built around the needs of diverse local communities using equality impact assessments.

- Multi-year and timely settlements for councils to allow councils to make plan and make meaningful financial decisions that improve value for money and financial sustainability.

- Certainty over financial reforms including the business rates reset, the Fair Funding Review, and reforms to other grants such as the New Homes Bonus including consulting on any potential changes in a timely manner.

- Council tax increases are not the long-term solution to the financial challenges facing local government particularly during a cost-of-living crisis. In addition, increases in council tax raise different amounts of money in different parts of the country and it would fall short of the sustainable long-term funding that is needed. However, to strengthen accountability to residents:

- Council tax referendum limits should be abolished so, when the time is right, councils and their communities can decide what increase in council tax is warranted to help protect or improve local services.

- Council should be given the powers to vary all council tax discounts including the single person discount which is worth around £3 billion a year.

- To improve the build-out rates of homes with planning permission and reduce the number of stalled sites, councils should be able to charge developers or landowners full Band D council tax for every unbuilt development.

- Make it easier for councils to recover unpaid council tax such as removing the need to go to the courts and remove the requirement for the entire annual sum to become payable if an instalment is missed.

- Business rates are an important source of revenue for local government – a further financial risk for councils if the country enters recession and businesses close - and we welcomed the Government’s acknowledgement of this in the conclusion to the Government’s Business Rates Review. The Government should consider what support businesses need as a result of increases in inflation, energy bills and the National Wage and continue to compensate councils for any business rates reliefs and for any freezes in the business rates multiplier or increases to it below the retail price index (RPI). Business rates could also be improved by:

- Giving councils more flexibility on business rates reliefs such as charitable and empty property relief.

- A review of exemptions such as where business happen to be located on farms.

- Further clampdowns on business rates avoidance along the lines of those introduced in Wales and Scotland to ensure that the rules on reliefs such as empty property and charitable relief are applied fairly.

- Giving councils the ability to set its own business rates multiplier, or at the very least be able to set a multiplier above and below the nationally set multiplier.

- Bringing forward changes in the basis of liability so that more is defined in statute; how this is framed should be the subject of a further consultation involving the LGA and councils. This is because many fundamental concepts such as beneficial occupation have been set by case law leading to results which may seem puzzling to the public, such as the fact that large vacant sites may not pay business rates.

- Consideration of alternative forms of income for local government including an e-commerce levy with the funding retained by local government.

- Allow councils appropriate freedoms to borrow and invest, without the need to seek prior approval from government, and make the making the flexible use of capital receipts arrangements permanent and available to fund all transformational and savings projects.

- Take measures to address the crisis currently facing local audit. This must include taking immediate steps to resolve the current issue with valuing infrastructure assets, if necessary, by statutory intervention. In addition, in the longer term, set up a new framework for local audit that is appropriate for the sector, and work with the sector on identifying opportunities for improving local authority accounting and accounts to make them simpler and more transparent and easier to audit.

Children’s services

Children’s services remain one of the most significant pressures on council budgets because of increasing demand and the increasing cost of services. LGA analysis shows that councils spent over £10.5 billion on children’s social care in 2020/21, nearly 25 per cent more than the £8.5 billion spent in 2016/17. Further analysis outlined in our submission to the 2021 Spending Review identifies outstanding pressures of £1 billion each year, with an additional £0.6 billion worth of pressures each year to maintain services at the current level of quality and access.

Increasing spend on children’s social care is largely a result of councils’ vital work in supporting children who are unable to live with their birth parents. The number of children in care has risen to a record high of 80,850, an increase that cannot be explained solely by population increase with the rate per 10,000 children now at 67 compared to 59 in 2011.

The complexity of children’s needs has also increased over time, including the emergence of increasingly severe mental health needs requiring more intensive support packages, additional social worker time and higher staff to child ratios in children’s homes. We can also see this illustrated in the doubling of the number of children waiting for placements in secure children’s homes in the year to April 2022 and a 462 per cent increase in applications to deprive children of their liberty over the last three years.

In addition to increasing demand, services face increased cost of delivery driven by measures introduced in the Covid-19 pandemic (for example, infection control in children’s homes), increased staff costs due to increases in the National Living Wage and as recruitment and retention becomes more challenging, and increased costs to providers such as energy and food costs. The impact of these increased costs can be seen clearly in council spend on placements for children in care.

The total reported spend on fostering and children’s homes placements in the independent sector has risen by 57 per cent since 2015-16 (driven by an 84 per cent increase in spending in the residential sector), despite children in care numbers only growing by 15 per cent in the same period.

There is a well-established link between poverty, deprivation and involvement with the child protection system. We have significant concerns about the likelihood of the current cost of living crisis pushing more families into poverty, and subsequently leading to more children and families requiring support from children’s social care. Measures to address this challenge have been outlined elsewhere in this submission.

Workforce challenges are also putting pressure on budgets. The impact of the pandemic has seen increasing numbers of children’s social workers either moving to children’s social care agencies or leaving the profession altogether. This is leading to an increasing reliance on agency workers. Research indicates that council spend on social work agency managed teams has increased from £7.9 million in 2020/21 to £22.2 million in 2021/22 – an increase of 181 per cent. The Independent Review of Children’s Social Care reported the additional cost of employing agency staff as approximately £26,000 per worker per year (53 per cent of the average social worker salary).

There are also significant financial challenges in delivering the services that children with special educational needs and disabilities (SEND) need. DfE figures show that over 473,000 children and young people have an Education, Health and Care Plan (EHCP) in England as of January 2022, an increase of 10 per cent or 42,000 over the previous 12 months, while the number of children and young people with an EHCP or statement of SEN has increased in every year since 2010. The number of initial requests for an EHCP rose by nearly a quarter (23 per cent) between 2020 and 2022.

We are pleased that the DfE has recognised this challenge and made additional high needs funding available, including via the ‘safety valve’ and ‘Delivering Better Value in SEND’ programmes. However, councils need long-term sufficiency of, and certainty over, funding to support children with SEND, including work to develop a plan that eliminates every council’s Dedicated Schools Grant deficit which currently stands at an estimated £1.9 billion, rising to £3.6 billion by 2025 with no intervention.

Many of the issues facing children’s services and SEND will take some time to address and we welcome Government’s commitment to developing an implementation plan for the IRCSC and ongoing close working on the proposals set out in the SEND Green Paper, as well as current work to tackle the urgent workforce challenges.

However, there are several key building blocks that could be achieved through the fiscal plan to support action and ensure children are kept safe and they and their families receive the support they need:

- Meet the £1.6 billion cost pressure already in the system to help to stabilise the children’s social care system to ensure that children are safe and families receive the support they need.

- Commit to funding additional support for families to reduce the pressure on children’s social care, as outlined in the Independent Review of Children’s Social Care, including:

- Financial assistance for carers of children on Special Guardianship Orders or Child Arrangement Orders (£463 million investment in year one)

- Extend foster carer support to improve retention of foster carers (£158 million investment in year one)

- Develop a plan to eliminate every council’s Dedicated Schools Grant deficit (approximately £1.9 billion).

- Invest in a trial of the national leadership programme for new children’s home managers recommended in the IRCSC.

- Fund an extension of the Return to Social Work programme to help tackle current challenges in children’s social work by bringing 200 social workers back into the profession.

- Give councils maximum local freedom and flexibility over the use of Apprenticeship Levy funds to help address workforce challenges, including the ability to pool levy funds to better plan provision across their areas, and use a proportion of the levy to subsidise apprentices’ wages and administration costs.

- Increase funding for children’s mental health services to provide the wraparound support increasingly needed by children, including community services, Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services and inpatient provision.

- Extend funding for family hubs to all areas, building on the 75 areas which have already received funding, to support the provision of services for families when and where they need them (£302 million).

Cost of Living

The rising costs of fuel, food and other essentials are combining with existing socioeconomic disadvantage and financial precarity within our places and communities to put millions of people at greater risk of both immediate hardship and reduced opportunity and wellbeing. Whilst some vulnerable groups, for example older people living alone, will be particularly in need of support, we are also seeing increased pressures on better off households, many of whom are turning to councils and local partners to seek support.

Financial wellbeing, resilience and capability underpin sustainable productivity and growth, by enabling people to concentrate their resources and capacity on acquiring new skills and progressing in work; giving people the confidence to invest socially and financially in their families and communities, and enabling people to stay mentally and physically well.

While the energy price cap is a hugely important measure, typical household gas and electricity bill will still rise from £1,971 to £2,500 a year from October. Average rents on new leases are more than 8 per cent higher than a year ago, with significant regional variations. In London, the average asking rent in July 2022 was 14 per cent higher than in July 2019; in Manchester 27 per cent higher and in Cardiff 36 per cent higher. Bread and cereals have risen by 12.4 per cent, milk cheese and eggs, by 19.4 per cent and oils and fats by 23.4 per cent. Interest rate rises will significantly increase costs for millions of mortgage holders.

Headline inflation was 9.9 per cent in August, but analysis by the Institute for Fiscal Studies suggests that because poorer households spend disproportionately more on gas and electricity they are likely to experience even higher rates of inflation: 14 per cent for the lowest income decile compared to 8 per cent for the highest.

Given these pressures, we were pleased that the Government acted on calls by the LGA, councils and partners earlier this year to increase and extend the Household Support Fund to the end of this financial year, as well as by earlier announcements to rightly prioritise support to families struggling with the rising cost of living.

Councils and local partners have delivered remarkable services and support and will continue to do what they can to protect people against higher costs, targeting help at those facing the most complex challenges. They will be on the frontline in responding to households approaching crisis point, but there is a risk of council housing, public health and discretionary financial support services being put under unsustainable pressure, particularly if benefits do not rise at the same rate as inflation and people struggling to make ends meet become worse off.

Covid demonstrated that councils can quickly rise to the challenge of delivering timely support and collaborate effectively with a wide range of partners whether through delivery of household grants/support, council tax rebates or business grants or through provision of advice and wrap-around services. Councils can be trusted to do so again as we enter a further period of extreme challenge, but they can’t tackle the problem alone. We need to strengthen and maintain a collaborative approach between national and local government and key partners in the private, public and voluntary sectors. Set out below are a range of interventions we are calling on the Government to support in terms of councils’ role in this system.

First, Government should ensure that a fair and sufficient mainstream benefits system is complemented by flexible and consistent funding for local welfare support.

- Maintaining identified funding for local welfare provision: A shift is required to move from short-term, prescriptive funding, as provided by the Household Support Fund, to sustainable funding to enable councils and partners to establish efficient, transparent support and referral pathways ensuring support is timely, fair and accessible. At least £500 million per annum should be made available for councils to support the persistent and rising numbers of people seeking assistance.

- Similarly, an approach that ensures councils have the flexibility to place an increasing emphasis on preventing crisis and strengthening financial resilience, which can ensure that councils are not just temporarily mitigating hardship but are able to work with households and communities to tackle the underlying causes of crisis and disadvantage, to reduce inequality, and to promote strong, integrated and economically enfranchised communities.

- Continuing to invest in improved data-sharing between the Department for Work and Pensions and councils, to better support poverty prevention initiatives including Pension Credit take-up and tenancy sustainment.

- Ensuring that Discretionary Housing Payment is adequate and fit-for-purpose, with annual settlements enabling councils to plan support efficiently, fairly and effectively. The LGA would like to work with colleagues in the Department for Work and Pensions on a long overdue review of DHP policy and funding.

- Ensuring the long-term viability of councils’ revenues and benefits service through sufficient funding, enabling them to deliver targeted support to those at risk of financial hardship and economic vulnerability, alongside housing, welfare rights and money advice services.

Secondly, the Government should work with councils to develop a more evidence-based, demand-led and outcomes-focused approach to improving households’ longer-term financial wellbeing and resilience across Government.

Over time, councils and their local partners should have the flexibility to shift sustainable local welfare funding from providing immediate crisis support towards building greater financial inclusion and resilience, which will underpin inclusive, sustainable economic growth and improved health and wellbeing.

To reduce the need for short-term crisis support, there needs to be a consensus on how we move forward and build resilience, capability and wellbeing through our wider welfare system, which includes not just benefits but employment support, housing, health and financial inclusion. Key measures of long term reform should include:

- Sustainable funding for welfare rights, money and debt advice services to ensure residents receive all the financial and legal support they are entitled to, are supported to avoid and escape debt and poverty traps, and are able to make limited household incomes and assets work as hard for them as possible.

- The impact of the cost-of-living crisis presents real and substantial risks around problem debt, and councils need the resources to strengthen their own approaches to debt recovery and support, and to sustain crucial partnership working with the Money and Pensions Service and other advice providers. Helping people to escape deficit budgets and borrow appropriately and affordably through improved advice, support and services will improve productivity and wellbeing and reduce costs to the taxpayer. In 2018 the National Audit Office estimated that problem debt costs the wider UK economy £900m per annum. Improving access to affordable credit and community banking: Our report exploring the role of councils in improving access to affordable credit and financial services for low-income households highlighted that that the provision of low-interest loans and other financial services tailored to people on lower incomes can be an effective component of local financial inclusion strategies, which can prevent people from turning to high interest pay-day loans, help with manageable debt consolidation, and enable people to manage fluctuations in income and expenditure.

- Engaging Public Health and addressing the wider determinants of health. Public health services have shown their value during the pandemic and are key to tackling health inequalities which will further increase as a result of the rising cost of living. Resources are needed to deliver on existing priorities and responsibilities – both now and in the coming years. Investing £900 million in the public health grant to return it to its 2015/16 level in real terms will enable councils to secure the foundations to enable the promotion of health and the prevention of ill health in their communities.

- Strengthen homelessness prevention services through the implementation of a cross departmental homelessness prevention strategy which looks at the drivers and levers of homelessness within central government policy and is bolstered by appropriate and robust funding through the Homelessness Prevention Grant. With cost-of-living pressures increasing, the number of social rented tenancy households owed a prevention duty has more than doubled and evictions from the private sector have also increased by 100%. Moving forwards, central government, councils and housing providers have to offer a more supportive approach to recovery and arrears. It’s also vital that Government acts fast to implement Renters Reform to ensure private renters have a home that is safe, stable and affordable.

- Aligning cost of living support with urgent investments into energy efficiency and net zero – establish a national energy advice support centre as committed in the Energy Security Strategy and invest in councils to extend and target local support into basic energy efficiency improvements which are cheap, quick and easy to install and are not provided by ECO 4 or other schemes.

- Work with councils to build an economy that increases prosperity and productivity for people across the country recognising the need to tackle social as well as geographic disparities.

Economic growth

Since the financial crisis of 2008, productivity in the UK has flat lined. Between 1998 and 2008, labour productivity was roughly 2 per cent. In the following decade this had dropped to 0.4 percent. As a result, the UK’s output per worker is lower than our main international competitors: the US, France, Italy and Germany.

Moreover, while parts of the UK are highly productive, the country experiences a significant degree of regional variation. Eight out of 10 areas with productivity in line with the UK average are in the Greater South-East. By contrast, nearly half of the UK’s sub-regions are 10 per cent below the UK average, with the lowest levels of productivity found in rural and coastal areas. As a consequence, while the City of London and Westminster are among some of the most productive areas in the world other parts of England have levels of productivity, below Hungary, Slovakia and Slovenia.

The impact and extent of these regional variations have been made more difficult to address by the prevalence of significant pockets of inequality even in relatively prosperous areas that resist top-down intervention from the centre. Even in London, the economic powerhouse of the country nearly sixty percent of children living in the area around Canary Wharf are in poverty, compared with only twenty percent a few miles away. Only councils with their in-depth knowledge of local communities and businesses can tackle these challenges with sufficient granularity.

Similarly, in places across the country some people continue to face inequality and disadvantage even as the economy grows more prosperous around them. Low earners were 2.4 times more likely to work in sectors shut down by the Coronavirus Pandemic with the typical pay for workers in shutdown sectors less than half (£348 per week) those that can work from home (£707 per week). BAME households were already twice as likely to be in poverty or be unemployed pre-COVID. IFS analysis of ‘shut-down’ sectors showed 15 per cent of employees were from BAME backgrounds, above the BAME workforce average of 12 per cent. Nine out of 10 BAME residents working in such vulnerable sectors resided in urban areas. Four in 10 BAME workers were employed in high COVID-19 risk occupations, in contrast to three in 10 white workers.

While UK unemployment has fallen during this period, from 7.8 per cent in 2009, to 3.6 per cent in 2022, recent figures have revealed a significant decrease in economic activity. People have withdrawn from the labour market due to ill-health, insufficient childcare and early retirement leaving firms struggling to cope with unfilled vacancies and rising labour costs.

The Government is right to put skills, retraining and job creation front and centre of its plan to kick start the economy. Investment and interventions to achieve this must connect at a local level and for all places if they are to support people of all ages – learners, unemployed people, career changers – as well as businesses and other employers of all sizes – progress to being part of a high skilled economy. A joined up and locally responsive employment and skills offer is critical to this and local government should be trusted to have lead responsibility for this locally.

The current skills and employment system is fragmented and unable to adequately address current labour market and productivity challenges including record high vacancy rates or tackle social and economic inequalities like low skills levels. Recent analysis by the LGA reveals that across England, £20 billion is spent on at least 49 nationally contracted or delivered employment and skills related schemes or services, managed by nine Whitehall departments and agencies, and delivered by multiple providers and over different geographies. No single organisation is responsible for coordinating these programmes nationally or locally, meaning there is no accountability over how the totality of provision is improving local outcomes. This makes it difficult to plan, target and join-up provision, leading to gaps in provision or duplication. Within this context, local government is striving to join up the system as best it can.

Productivity drives pay rises and contributes to higher living standards. As the previous Government’s Levelling Up White Paper set out, it is not the only priority facing the UK. Future growth depends on our success in spearheading the transition to net zero and developing a resilient society able to better withstand the impact of global instability and rapid changes in science and technology. However, if the country is to avoid the prospect of a return to the stagflation of the 1970s with the consequent collapse in real wages and growing poverty the nation’s anaemic and unequal growth must be addressed.

Local authorities understand the urgency underpinning the Government’s recently announced Growth Plan. They recognise the need for efficiency, speed and the value of public policy interventions that go with the grain of local economic conditions and deliver the best outcomes for communities and country. They also believe that an over-reliance on Whitehall systems and silos has led to waste and a concentration of power at the centre has been unable to connect people from all walks of life with the proceeds and opportunities of prosperity. In forging ahead for future growth councils are uniquely placed to balance delivery at pace with the concerns of local communities: new homes that people want to live in, new roads that respect our access to precious green space, new mobile masts that deliver genuinely improved connectivity without unnecessarily blighting the landscape.

To build an economy that speaks to the immediacy of the cost-of-living crisis as well as the longer term demands of sustainable and resilient growth, we are calling on the Government to work with local authorities to:

- Bring sub-national government expenditure on economic development into line with our major international competitors, such as Germany. Give local authorities the tools and resources they need to drive growth and address regional imbalances in productivity by delivering on the commitment to offer every area in England that wants one a devolution deal by 2030.

- Pilot a new approach to public service investment, by asking areas to come forward with radical proposals to bring together budgets and public services under the leadership of local government.

- Boost local productivity and save money on costly competitions between areas. LGA research estimated that the average cost to councils in pursuing each competitive grant was in the region of £30,000, costing each local authority roughly £2.25 million a year chasing down various pots of money distributed from across Whitehall. Start with the existing commitment in the Levelling Up White Paper to bring together the long list of individual local growth funds.

- Help councils bring forward existing investment programmes by: expediting allocations for all current grant schemes (Housing Investment Fund, Levelling Up Fund, Local Transport Schemes), relaxing the conditions around their expenditure and, within the context of high and rising inflation, extend deadlines to support delivery where completion timescales are now under pressure.

- Create a single, locally held schools capital funding pot with a five-year settlement and allow surplus schools’ sites including academies to be sold with the proceeds ringfenced for reinvestment in schools.

- In line with Highways England, Network Rail and Mayoral Combined Authorities, provide a 5-year allocation for highways and local transport capital and maintenance programmes. This will provide certainty for private sector partners and delivery organisations and will help councils to design transport infrastructure that meets the future needs of communities and business, reflecting their changing travel patterns and new technologies, such as electric vehicles. Future funding should reflect cost inflation in capital projects, which is running at 21 per cent in many areas. Buses remain by far the most popular form of public transport. The Government should fully commit to the reforms and investment as set out in its National Bus Strategy to ensure bus travel remains affordable, people can access work opportunities.

- Reverse the decision to create a centralised Office for Local Government, saving scarce resources and avoiding duplication. The LGA, through its public benchmarking tool, LG Inform, already makes available both financial and performance data about every council. LG Inform allows users to compare their council with any other council. It is hard to see what additional value the new Office for Local Government would provide.

- Give democratically elected local leaders the power to work with partners to join up careers’ advice and guidance, employment, skills, apprenticeships, business support services and outreach in the community, by taking forward the LGA’s Work Local proposal. A cost benefit analysis shows that for a typical medium sized authority, it could improve employment and skills outcomes by about 15 per cent, meaning an extra 2,260 people improving their skills each year and an extra 1,650 people moving into work. This would boost the local economy by £35 million per year and save the taxpayer an extra £25 million per year.

- More than 1.1 million homes granted planning permission in England in the last decade are yet to be built, with 9 in 10 planning applications being approved by councils. To speed up delivery, the Government should give councils powers to incentivise developers to build housing more quickly. For example, to charge developers full council tax for every unbuilt development from the point the original planning permission expires; it should also be easier for councils to use their compulsory purchase powers to acquire stalled housing sites or sites where developers do not build out to agreed timescales.

- Councils can play key role in local energy planning, and should have levers to help ensure the grid is fit for housing growth, the electrification of heat, and to exploit the benefits of renewable energy.

- In order to ensure locally generated investment is focused on addressing local need the Government should reform Right to Buy by extending the spend deadline from three years to five, allowing councils to retain 100 per cent of receipts and increasing the proportion of retained receipts that can be used to meet the cost of replacement homes.

- Streamline the planning and procurement system by: continuing with procurement flexibilities for councils for all projects related to public housing and public building projects for 12 months; incentivise the use of Local Development Orders (LDOs) to allow Councils to introduce new locally-determined permitted development rights for all projects related to public housing and public building projects e.g. schools, health facilities, libraries, leisure centres; change rules around 106/CIL such that councils can invest upfront in schools and roads and claw back from associated developments; remove viability as a material planning consideration.

- Our high streets and town centres remain vital social and economic hubs, however, they remain challenged with High Street vacancy rates at 14% and shopping centres at 19%. This masks sub-regional variation, with some places seeing High Street vacancy rates approaching 1 in 4 of all buildings. Along with growth funding certainty, councils need better local powers to shape their town centres, making them more resilient to economic shocks. This includes streamlining the CPO (compulsory purchase orders) process and removing nationally set permitted development rights.

- To meet Government's mobile and broadband targets, and accelerate rollout, we are calling on Government to provide funding for councils to build internal expertise and put in place local digital champions who would support the coordination of local delivery.

- There are currently 1,188,762 people on council housing waiting lists. Research for the LGA and partners has found that investment in a new generation of social housing could return £320 billion to the nation over 50 years. It also found that every £1 invested in a new social home generates £2.84 in the wider economy with every new social home generating a saving of £780 a year in housing benefit.

- Councils will play a key role ensuring the 1.7 million people who rely on technology enabled care are not left without a connection or digitally compatible device as a result of the Public Switch Telephone Network switchover, and we are calling on Government to provide funding for councils to support their preparation for the upgrade to next-generation digital networks.

- Set out a clear vision for how the NHS and local government can align investment around place to both support improved health outcomes and improved economic growth. We know that where devolution of health and social care has taken place, areas have seen significant benefits for local residents. For example, the Greater Manchester Population Health Plan update showed a substantial increase in school readiness and a smoking prevalence rate falling twice as fast as the national average.

- Similarly, the inclusion of “helping the NHS to support broader social and economic development” as a core purpose of an ICS provides the NHS with the opportunity to develop their role as a driver of local growth. Their ability to drive change as an employer, procurer and place shaper should not be underestimated, but they will only achieve partial success by working alone. Government needs to provide flexibility within budgets to allow local government and ICSs to pool resources to allow for alignment of local anchor strategies, and how these can build on existing economic growth and population health policies.

Climate change

Earlier this year the latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) assessment concluded that: “The cumulative scientific evidence is unequivocal: climate change is a threat to human well-being and planetary health. Any further delay in concerted anticipatory global action on adaptation and mitigation will miss a brief and rapidly closing window of opportunity to secure a liveable and sustainable future for all.”

The combination of flooding, heat, drought, ecosystem collapse and global political instability has the potential to create significant damage to the UK’s economy as well as the health and well-being of our communities.

Public concern for the environment is high, with more than 80 per cent of the public somewhat or very concerned about climate change. Opinion polling also continues to show significant levels of support for net zero, and the extent to which our way of live is impacted will become more acutely felt as flooding, heat, drought, shortages, and economic damage escalate.

Climate action is positive on multiple fronts. Alongside safeguarding a habitable future, associated co-benefits of the move to net zero tackle the greatest concerns in our communities, our cost of living, our health, and our economy. There are huge opportunities to shape the green recovery, locally, nationally, and internationally.

Over 300 local authorities have declared climate emergencies and are in the process of developing plans to deliver against ambitious targets. As local leaders, only councils can mobilise and join-up community action on climate change and pull a wide range of levers to deliver local action that reduces emissions and adapts to the impact.

As the Government’s Net Zero Strategy summarised, councils can influence 80 per cent of emissions from their places, they have direct influence over a third of emissions, and have direct responsibility for three to five per cent of emissions.

However, this potential is a long way off being realised, set out below is an approach to redress this over the medium and short term.

First, the Government must support councils to lead place-based approaches to hit net zero targets, which cost three times less than a centralised approach and deliver twice the social and financial returns.

New research has revealed dramatic benefits of joined-up, place-based approaches which can achieve significantly greater returns on investment, achieved primarily through decarbonising heat, buildings, and travel.

Accelerating Net Zero Delivery from the UKRI report with PWC, University of Leeds, and Otley Energy, found that a centralised – or ‘place-agnostic’ - approach would take £195 billion of investment in things like heat pumps, insulation, and electric vehicles, to meet the targets set out in the sixth carbon budget; and would release £57 billion of energy savings, and £444 billion of wider social benefits over the next 30 years.

By contrast, under a scenario taking a place-specific approach, £58 billion of investment would be needed to meet the same targets. In the process it would generate £108 billion of energy savings for consumers, and £825 billion of wider social benefits over the next 30 years. The benefits of place-based approaches are significant.

Second, local approaches to net zero are also critical for understanding, planning, targeting, and connecting the range of interventions needed to enable the ‘ready to pay’ markets to grow.

For instance, on decarbonising housing, councils can develop strategies that link public investment in retrofitting social homes to local efforts to build supply chains and green skills to pump-prime market growth. Councils can set the signals on the most appropriate technical solutions for different areas and help strategically build the grid capacity.

As leaders in the community, councils can connect this with strategies to inspire households to invest themselves, connecting and mobilising public services and community groups – as they did in the Covid-19 pandemic – to create an offer that provides advice, protections, and incentives to support residents make the decision to decarbonise their homes.

Furthermore, the UK Cities Climate Investment Commission and UK Research and Innovation are beginning to demonstrate that councils are uniquely able to build a pipeline of net zero projects with the scale to crowd in significant levels of private capital. Subject to capacity, technical skills and a clear public finance landscape, councils can lead a step change in private investment essential to the transition.

Third, councils are also uniquely able to connect the local path to net zero while helping resolve some of the immediate challenges and concerns facing families.

For instance, as a central fixture of the local welfare support system, councils can combine efforts to support people with the cost-of-living crisis with advice and basic energy efficiency measures that permanently reduce energy bills. Our modelling suggests £12.7 billion will be wasted through leaky homes over the next two years, with a third of that cost being incurred by the Government under its Energy Price Guarantee. There is an opportunity for urgent retrofit effort that accelerates the long-term decarbonisation effort. However, the impact on families is urgent, and councils can also help rapidly deploy basic energy advice and simple draught proofing measures that can make a big difference to households.

Similarly, the public health dangers of cold homes in the winter or extreme heat in the summer can be reduced by councils connecting health services with efforts to improve energy efficiency. Wider action to promote active travel, increase the prevalence and availability of nature and green space, and improve air quality are also other primary objectives that councils can best bring together in places.

Public interest, concern and engagement with our adaptation effort will likely grow in the years ahead as the frequency and intensity of extreme weather events escalate, and the impacts on health, quality of life, and the economy grow.

Councils will play a central role in adapting, preparing, and responding to the majority of the sixty-one climate risks identified by the Climate Change Risk Assessment. They can leverage their influence as community leaders and conveners, with responsibilities across housing, planning, transport, infrastructure, environment, environmental health, public health, welfare, emergency response, community safety and more.

Like net zero, the adaptation effort will require every part of our society and economy, the scale of adaptation is significant and predominately place-based. Councils can be central to closing the widening gap between the level of risk we face and the level of adaptation underway. For many councils, this starts with resolving the vulnerability and role of their own services.

The Government should work with councils to develop a net zero and adaptation delivery and investment framework, which aligns and clarifies national and local leadership, collaboration, and delivery roles across priority issues such as decarbonising heat and buildings, transport, energy in every place.

In June 2022 the Climate Change Committee concluded that around 60 percent of UK emissions still require a tangible decarbonisation plan. And the June 2021 the Committee presented alarming new evidence that adaptation action has failed to keep pace with the worsening reality of climate risk.

The current approach will unlikely leverage the potential of place-based approaches, ‘due to gaps in powers, policy and funding barriers, and a lack of capacity and skills at a local level’. Additionally, without some level of coordination, the UK risks pursuing a fragmented strategy towards net zero, and climate adaption.

We believe this framework has two key elements: place-based funding and local capacity to deliver.

The funding landscape for local government, net zero and climate change adaptation is centralised, complex, increasingly competitive, and uncertain, where councils are forced into chasing for small pots of investment from a wide range of shifting funding streams

The response to climate change shouldn’t be a competition. The approach limits the scope for strategic, coherent place-based approaches, and the social and financial benefits this returns. It doesn’t enable councils to develop projects of the scale and ambition to attract the private capital. It creates a mountain of bureaucracy and duplication within central and local government. It stifles innovation. And it means some areas do not receive any funding at all.

As part of a wider net zero delivery and investment framework, local and central government should work together to develop broad multi-year place-based funding allocations to deliver the range of agreed objectives – for instance to support housing retrofit and decarbonisation, decarbonise transport across places, and spearhead the nature recovery.

Most of councils’ revenue spend on climate change is from core budget, through services like housing, economic development, planning, transport. This capacity is critical to developing the projects that deliver net zero on the ground, however it is significantly limited due to wider financial and service pressures where councils have statutory duties and, as this submission explains elsewhere, these pressures are going to rise significantly.

When national funding is made available to help councils to build capability and capacity on net zero, it is often tied up in short term competitive schemes, meaning those with the capacity to write bids are most likely to benefit from additional capacity, while those without it continue to struggle. Further, it significantly curtails the impact public investment can have, for instance in attracting private investment, or aligning support for growing demand with support for growing skills and supply chains.

Local and central government should review and explore the critical areas to build capacity in councils, linked to the wider delivery framework and place-based allocations. Working with the LGA, Government should help all councils build in house capacity, to share and pool resources, and consider national or regional technical assistance support in key areas for instance in bringing forward projects suitable to private capital investment.

In addition to this longer-term approach to reform we also believe there are a number of actions, the Government can work with councils on in the short term.

- Align cost of living support with urgent investments into energy efficiency and net zero – establish a national energy advice support centre as committed in the Energy Security Strategy and invest in councils to extend and target local support into basic energy efficiency improvements which are cheap, quick and easy to install and are not provided by ECO 4 or other schemes.

- Bring forward earmarked investment – bring forward previous spending commitments to accelerate delivery and increase scale on priority issues. For instance, bringing forward investment in the Social Housing Decarbonisation Fund rather than phasing it over 10 years.

- Support climate action everywhere – shift existing spending away from competitively accessed schemes and towards allocations to all places, including with a capacity building element. For instance, less that 50 percent of places that bid for funding for national bus strategy received support. We acknowledge some funds will need topping up to ensure every place has the opportunity.

- Support climate action through everything – all public investments can and should help support the reduction of emissions or the adaption to change and the associated co-benefits. For instance, shaping spending across the range of growth, levelling up, infrastructure, housing, transport agendas.

- Provide flexibility in schemes for councils to innovate – build flexibility into all grants, for instance relaxing time frames and measure success through outcomes rather than spending speed. For instance, allow councils to use social housing decarbonisation grant as flexibly as they like to reduce emissions, rather than restrict its usage. And allow grant funding for innovative projects, currently this is often not permitted meaning councils must borrow to fund innovation which is less desirable.

- Be smart with funding – extend timeframes and provide some flexibility around bidding, short time frames for any bidding programmes creates the risk of funding the fastest rather than the best projects. Some funding opportunities, like Salix, run on a ‘first come first served’ basis which amplifies this risk.

- Reduce bureaucracy and red tape – align existing administration and accounting as far as possible, the current landscape of schemes creates an industry in auditing, accounting, and other administration. This is swamping council finance project teams and creating replicated bureaucracies across central government.