About this report

The report comes at a time when commissioners and providers of sexual health services have been making repeated calls to the government to address the long-term funding and capacity challenges across local authority commissioned sexual health services.

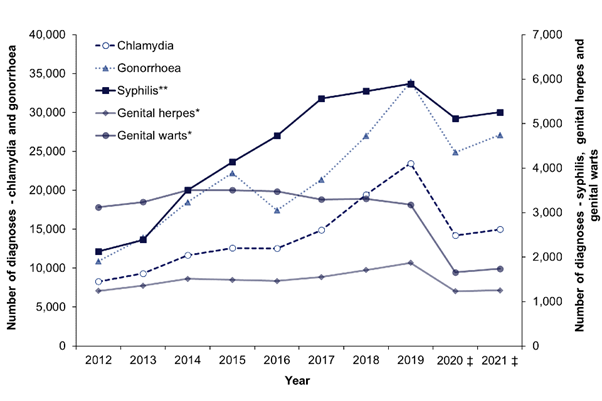

In the context of the dramatic increases in syphilis and gonorrhoea diagnoses, the continued spread of antibiotic-resistant sexual infection, challenges accessing contraception and the evolving spread of Monkeypox, it is more important than ever to ensure that sexual health is prioritised and appropriately funded.

The LGA and English HIV and Sexual Health Commissioners’ Group (EHSHCG) have produced this report focusing on demand and funding pressures. The report delves into the trends since local authorities took responsibility for sexual health services in 2013, looking at the social and economic context in which they occur.

Councillors David Fothergill Chair LGA Community Wellbeing Board, and James Woolgar Chair English HIV and Sexual Health Commissioners Group.

Key messages

- Significant increase in the number of consultations at Sexual Health Services over the last 10 years.

- Number of screens and the overall number of services offered has increased, public awareness of Sexually Transmitted Infections (STIs) and contraception has grown.

- Local councils have been engaged in one of the biggest modernisation exercises in the history of public health, such as a rapid channel shift to online consultations, app, home testing and home sampling.

- Evidence from across the sector shows the capacity of councils to further innovate and create greater efficiencies is now limited.

- Unless greater recognition and funding is given to councils to invest in prevention services, a reversal in the encouraging and continuing fall in some STIs and more unwanted pregnancies is now a real risk as is their ability to respond to unforeseen challenges such as Monkeypox.

- Behavioural change has increased demand.

- Equitable access to contraception remains a problem.

Context

In July 1916, the Local Government Board issued the Public Health (Venereal Diseases) Regulations. This began the process of providing free, confidential diagnosis and treatment for sexually transmitted infections (STIs) in the UK.

The Regulations were the enactment of the recommendations of the Royal Commission on Venereal Diseases, which issued its report in 1916. At that time syphilis death rates were 22-46 per million, 17 per cent of pregnancies in families with syphilis resulted in miscarriages or stillbirths, 30 per cent of children in blind schools were there due to syphilis and 50 per cent of infertility in women was due to gonorrhoea. Added to this mix was World War I and an explosion of STIs - during the war about 5 per cent of men in Britain’s armies were infected with an STI and over 400,000 British or allied troops were admitted to hospital due to a sexual infection.

In a similar fashion, the modern birth control and family planning movement in the 19th Century led to improved access to contraceptive advice and supplies for women. Campaigners were concerned about inequity of access even then, and referred to the need for ‘working class women’ to be able to access supplies to reduce overcrowding and prevent ill-health related to pregnancy and infant mortality. Indeed, appropriate baby spacing and timely intervals to improve outcomes for mother and child were mentioned even then. There is a vast array of documented evidence now to support these claims that 12-month intervals improve outcomes.

1973 saw a move to free family planning and open access provision. In 1993 the Faculty of Sexual & Reproductive Health (FSRH) came into being, overseeing training, quality, standards and provision across the discipline. It encouraged fairness and equity of access for all amongst its many goals and objectives. This is something that unfortunately, in recent times, we have not been able to continue, or stick to, due to restrictive policies and/or lack of funding. We have moved back to a point of inequity and inconsistency due to inadequate funding settlements that we must come out of if we are to improve sexual and reproductive health outcomes for all.

In 2013, commissioning arrangements for sexual, reproductive health and HIV were introduced as part of the implementation of the Health and Social Care Act 2012 and were further detailed in ‘The Local Authorities (Public Health Functions and entry to Premises by Local Healthwatch Representatives) Regulations 2013’. Move forward to 2022 and sexual and reproductive health services are commissioned by local councils to meet the needs of the local population, including:

- contraception

- STI testing and treatment

- sexual health aspects of psychosexual counselling

- sexual health specialist services

- HIV social care

- wider support for teenage parents.

Grasping the responsibility for sexual health commissioning since the transfer of public health to local government in 2013, councils have been working hard, in collaboration with NHS partners, to maintain and improve access for their residents to sexual, reproductive health and HIV services and to ensure seamless pathways of care.

The challenges are great. Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and unplanned pregnancy are amongst the most important contributors to poor health, particularly in the most deprived neighbourhoods. STIs are often asymptomatic. If left untreated, they can cause pelvic inflammatory disease or infertility, and may be transmitted to others.

In 2021, there were 311,604 diagnoses of new STIs among England residents, a similar number compared to 2020.

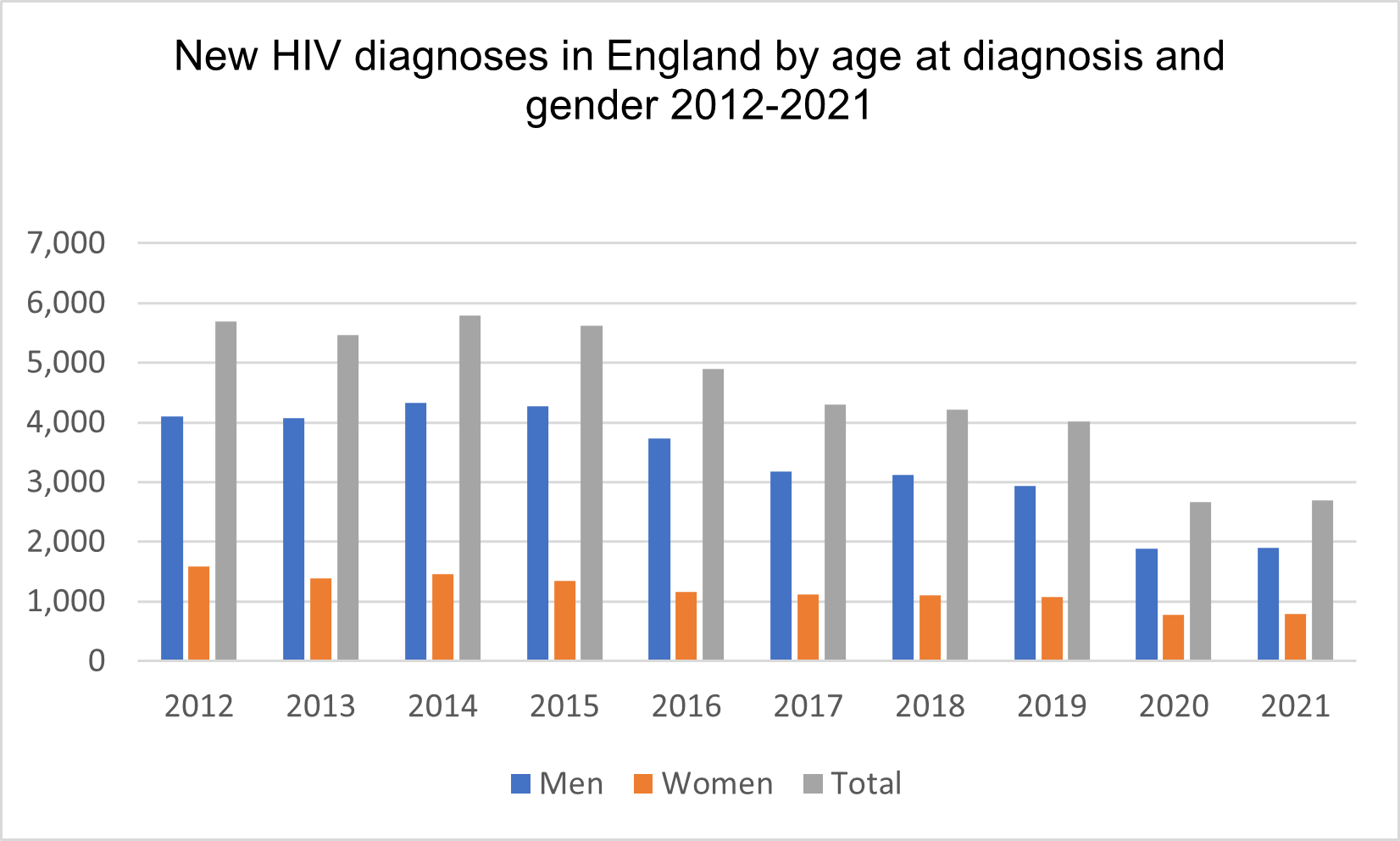

New diagnoses of HIV have recently declined thanks to treatment coverage and new prevention drugs, but late diagnosis, the leading cause of premature death and disease among people living with HIV, remains too high. A key strategic priority is to decrease HIV-related morbidity and mortality by reducing the proportion and number of HIV diagnoses made at a late stage of infection. People who are diagnosed late are estimated to have lived unknowingly with HIV for three to five years and have a ten-fold risk of death compared with those diagnosed promptly.

A consistent fall in teenage pregnancies over recent years, down to the lowest rate since 1969, is a testament to the systematic application of successful strategies, including education, support and access to comprehensive sexual health services. However, the substantial variation in rates between local authorities, ranging from 2.1 to 30.4 conceptions per 1,000 15- to 17-year-olds, leaves no room for complacency.

Investment in sexual health services remains one of the public health “Best Buys“, it significantly improves peoples’ general health and mental wellbeing.

There is a growing base of literature which has evaluated SRH interventions for their impact and cost-effectiveness. A good example is contraception, for which an investment of £1 is estimated to return £9 of cost savings to the government. Public health services save money, savings which are shared across the public sector including NHS and local authority budgets.

The COVID-19 pandemic has of course had an impact. However, the pandemic also shone a light on the inequalities that are also at the heart of vulnerability to poor sexual health across the country. The full impact of the pandemic on wider public health is yet to be fully understood.

Reductions in funding

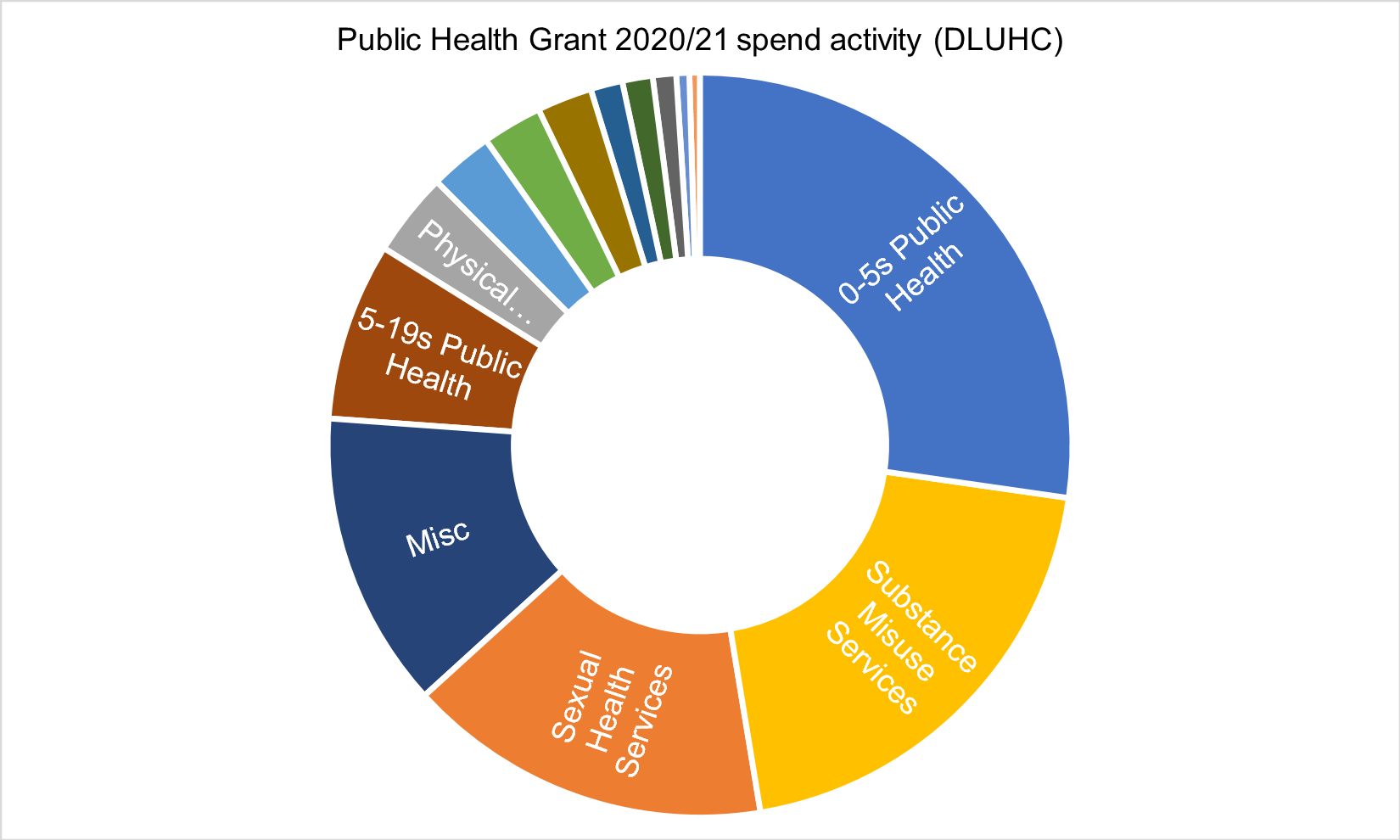

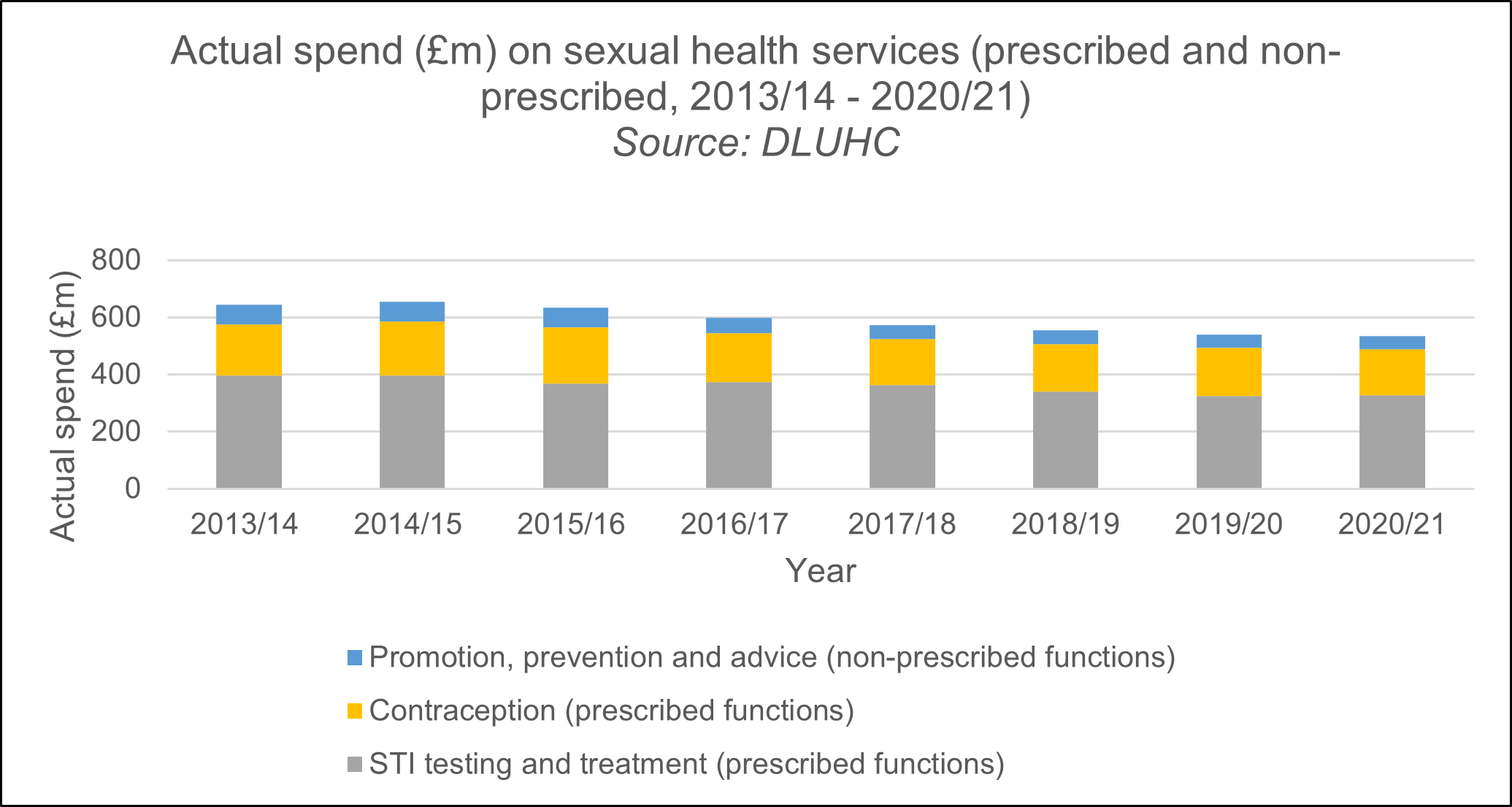

Councils currently invest more than £534 million a year in sexual, reproductive and HIV services. It amounts to the third largest area of public health spend (Fig 4), only drug and alcohol treatment and the provision of zero to five-year-old public health services spend more.

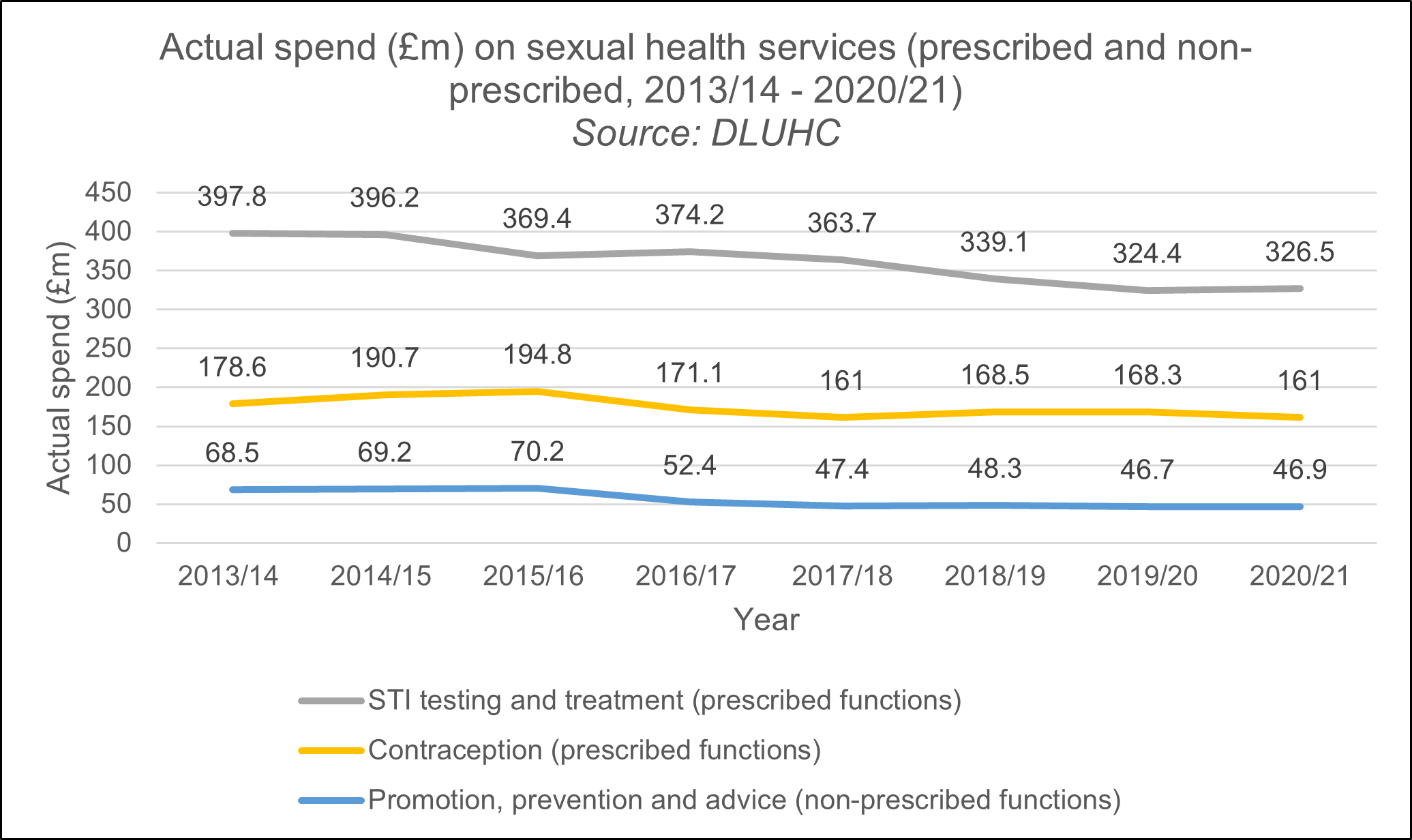

There is no doubt that sexual health services are under intense pressure financially. The public health grant to local councils used to fund sexual health services was reduced by over £1bn (24 per cent) between 2015/16 and 2020/21. Across England, spending on STI testing, contraception and treatment decreased by almost 17 per cent between 2015/16 and 2020/21, as local councils implemented these cuts (Fig 5).

Reduced funding has made it a significant challenge for them to respond at the scale needed. Government cuts to councils’ public health budgets has left local authorities struggling to meet increased demand for sexual health services.

Cuts to spending on sexual health, as with other areas of public health expenditure, are a false economy because they lead to higher financial costs for the wider health system.

Inadequate sexual health services may also lead to serious personal long-term health consequences for individuals and jeopardise other public health campaigns such as the fight against antimicrobial resistance.

Commissioners are particularly concerned about cuts to health adviser posts in clinics. These are professionals trained in giving advice to patients newly diagnosed with infections, and in tracing and notifying current and past sexual partners so that they can be brought in for testing. Cuts to outreach services that target high-risk groups such as sex workers and men who have sex with men; and to sexual health advice, promotion and prevention services leave services and vulnerable populations increasingly exposed.

Behavioural factors

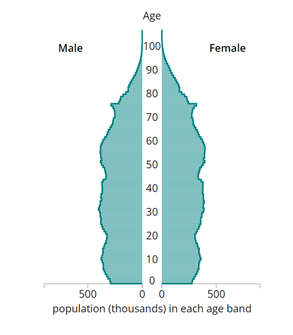

It is increasingly important to understand the evolving epidemiology of STIs in older adults so that behavioural factors, service delivery, and clinical and public health interventions can be ready to respond. Like many high-income countries, England has an ageing population, with those aged over 45 years forecast to grow by 3.87 million people between 2022 and 2042.

Recent figures from UKHSA have revealed that the number of over-65s who caught common STIs rose from 2,280 in 2017 to 2748 in 2019, an increase of 20 per cent. Indeed, a 2019 report by then PHE, stated that at that stage the rates of STIs in older age groups were increasing, with the largest proportional increase in gonorrhoea and chlamydia seen in people aged over 65. Sexual health services have observed the growth of the sexual practice ‘chemsex’ in the UK. The term chemsex refers to group sexual encounters between gay and bisexual men in which the recreational drugs GHB/GBL, mephedrone and crystallized methamphetamine are consumed. Where drug use takes place in a sexual context the risk of transmission of HIV, hepatitis B and C and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs) increases.

This has greatly impacted the volume and complexity of work that sexual health services are therefore dealing with. Recent evidence has suggested that chemsex interactions have increase, particularly among men who have sex with men (MSM) and that this has led directly to increased attendances at sexual health clinics, notably in cities/urban centres. The use of smartphone apps where individuals can identify romantic and sexual partners – ‘dating apps’ - has increased significantly since 2012.

It is widely speculated that the use of dating apps has led to an increase in the incidence of sexually transmitted infections (STIs); among MSM and heterosexual populations, particularly in young adults. Indeed, there have been a few studies into the impact and role of dating sites and apps and links to increasing prevalence of STIs. Research has found that finding sexual partners through geosocial networks and dating apps enables users to have a greater number of sexual partners with increased turnover, consequently decreasing safe sexual practices and increasing the chance of contracting STIs. However, research is currently limited within this area.

The ease at which certain parts of our population can access these dating sites is greater than ever before. Technological/digital innovations provide a raft of potential for improving sexual health service access, proximity and outcomes, however, the high use and access to smartphones and dating apps comes at a cost. According to latest Ofcom statistics (late 2018) we now live in an age where circa 80 per cent of the population own a smartphone or digital device ideal for remotely accessing services or using dating/hook up sites.

This rises to 95 per cent+ amongst the 15–24-year-old population, which as sexual health statistics show, is a group disproportionately affected by sexual ill-health and where we have seen some of the largest increases in STI rates. The World Health Organisation reported in 2019 that dating apps and sexual health stigma are driving a surge in STIs and untreatable strains daily.

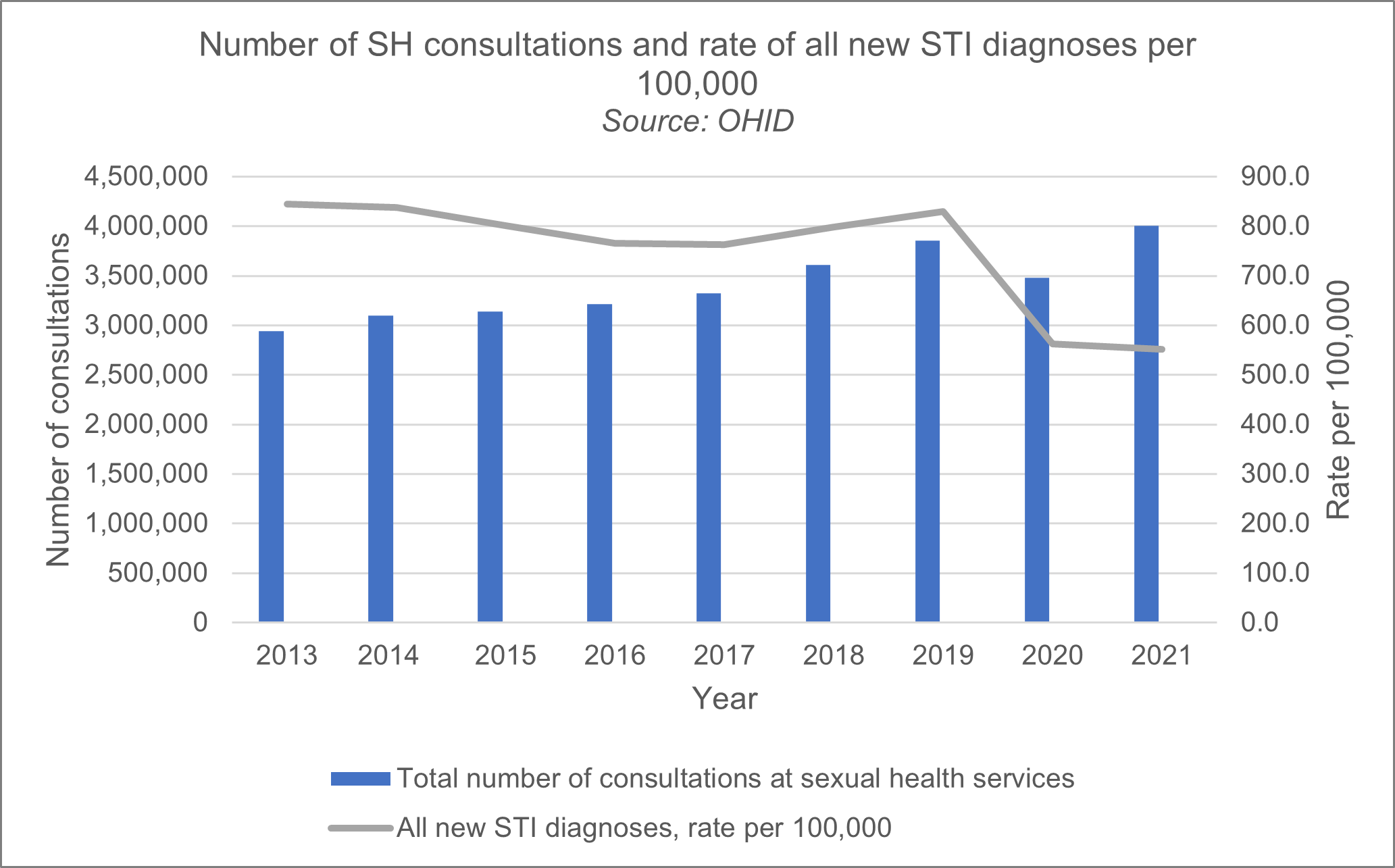

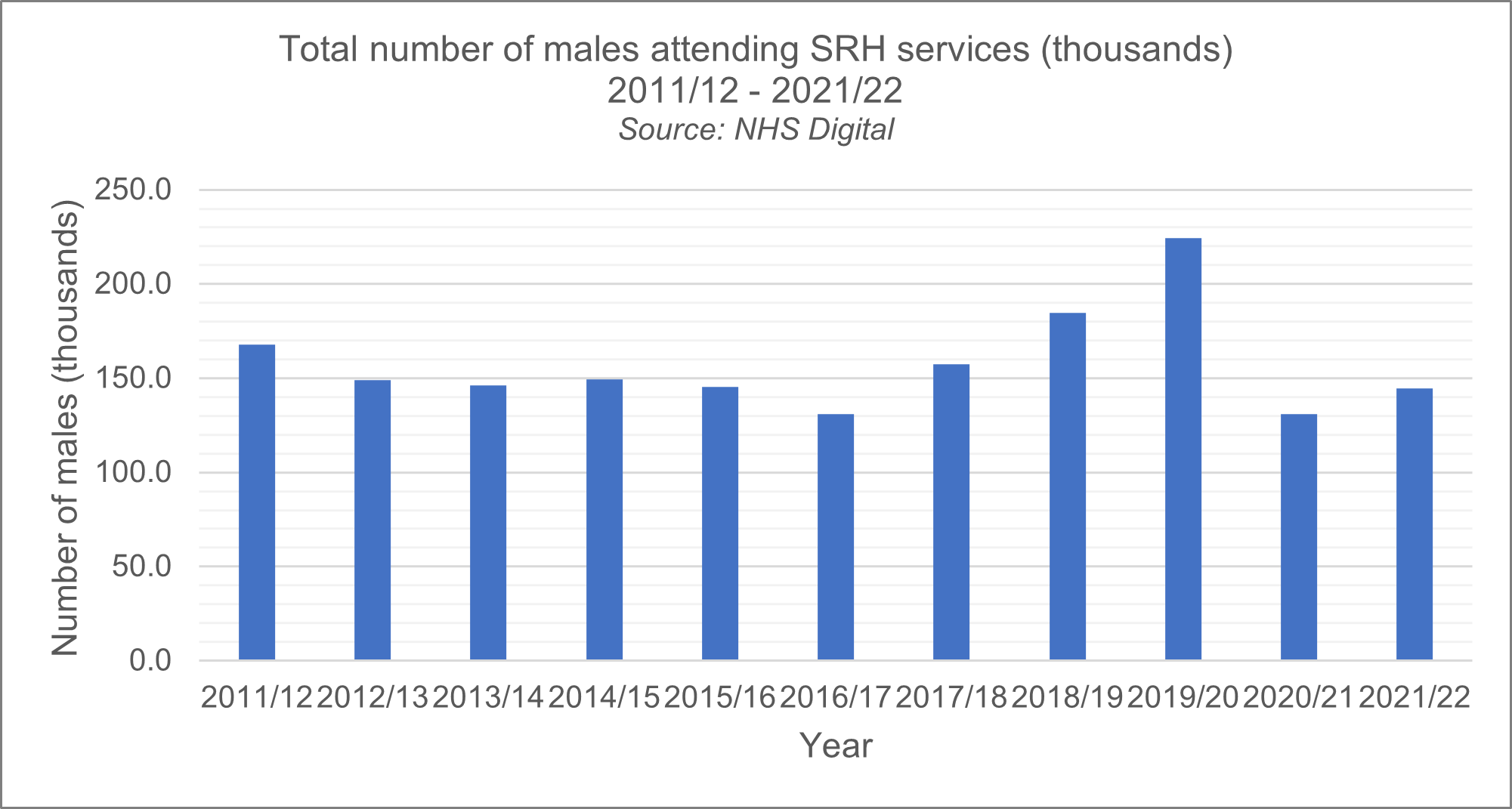

Skyrocketing attendance

It remains hugely encouraging that attendance at sexual health services has increased over the last ten years, this is incredibly positive news. People of all ages are rightly taking action and are more aware of their own sexual health. Demand has skyrocketed, testing has increased and the public’s awareness of STIs and contraception has grown.

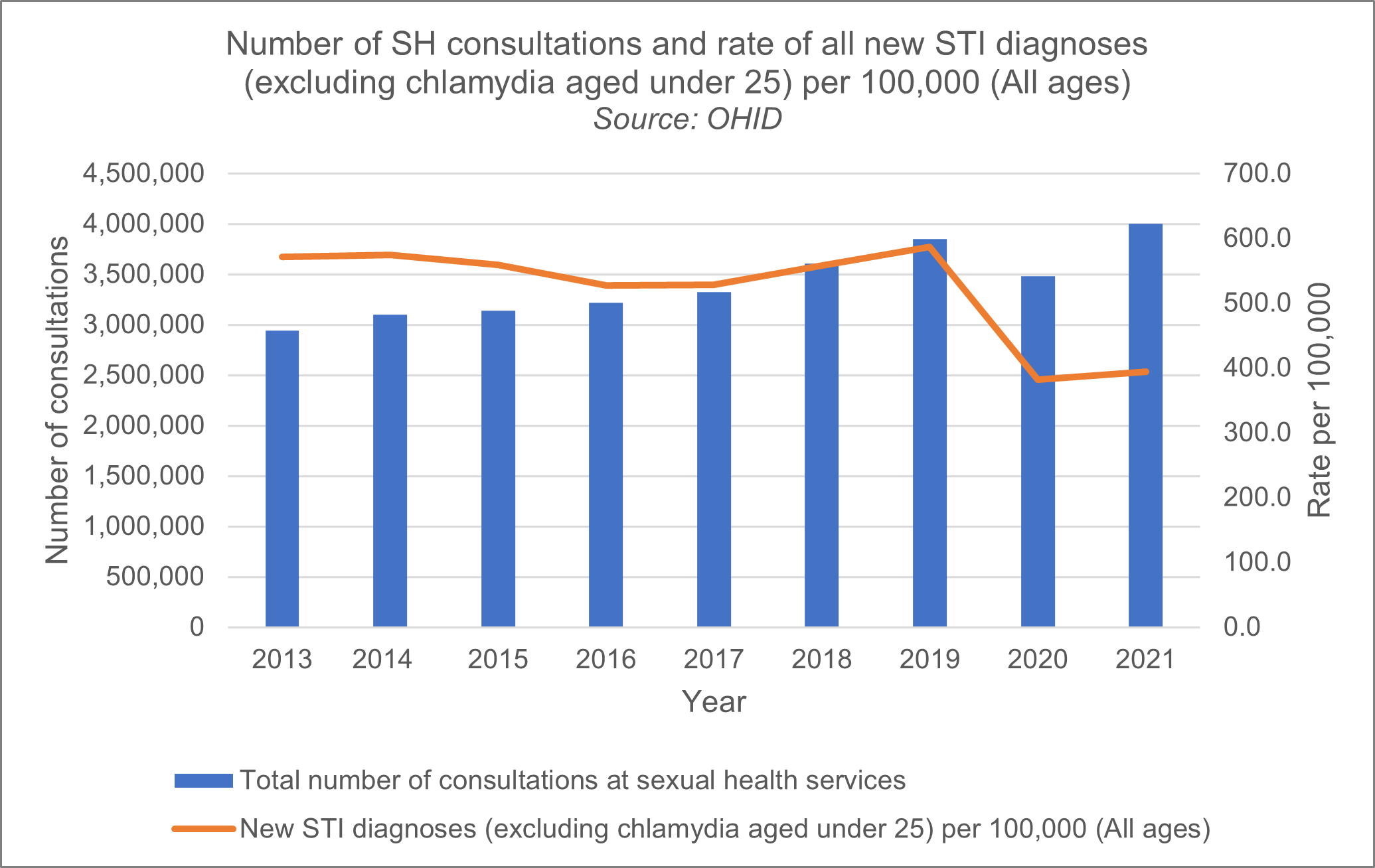

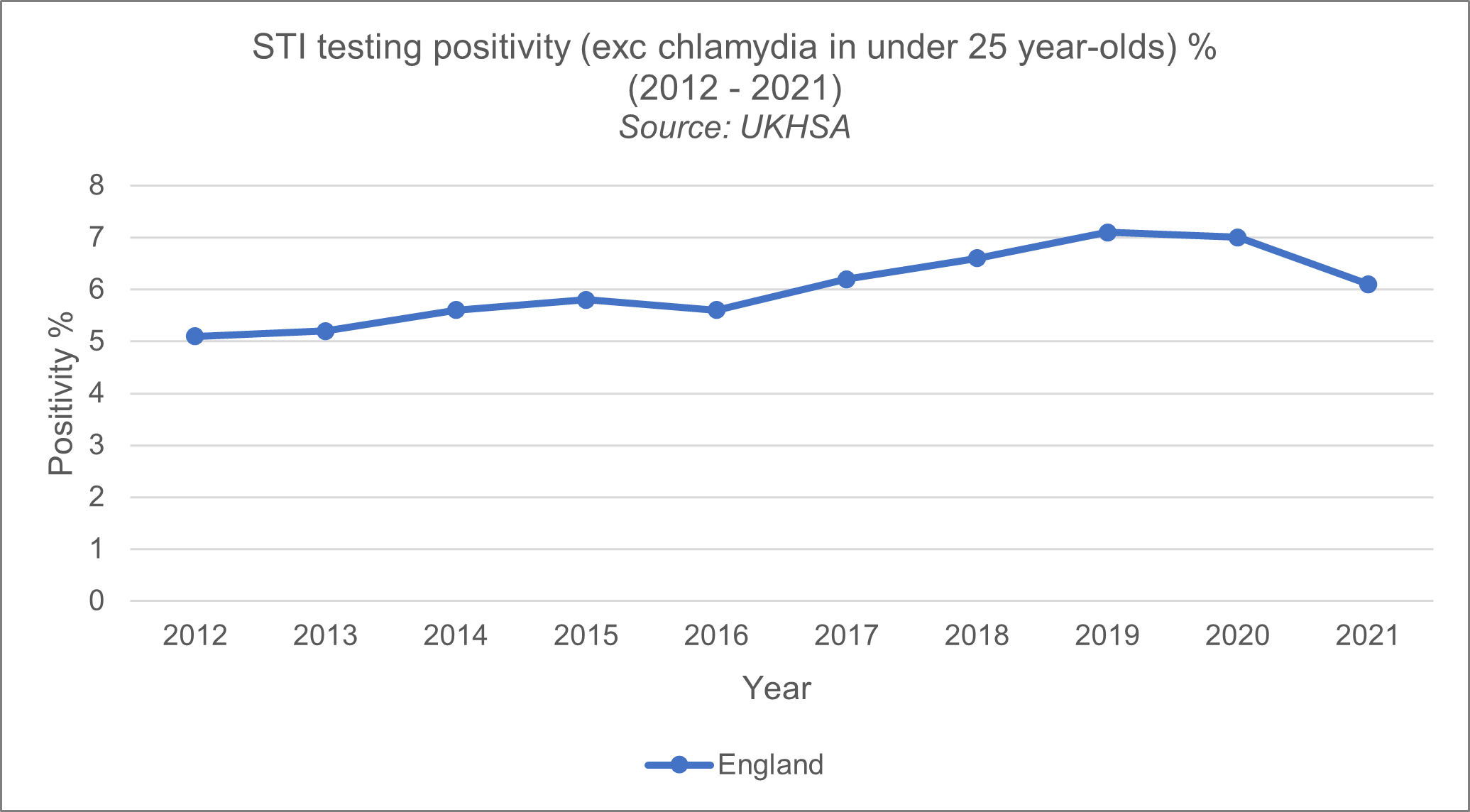

This is incredibly positive, but this does create real pressures for the service. UKHSA reports that in 2021, there was a total of 4,002,827 consultations at SRHs, a 15.7 per cent increase compared to 2020 and an increase of 36 per cent since 2013. In 2021, there were 1,949,940 sexual health screens (diagnostic tests for chlamydia, gonorrhoea, syphilis, and HIV) delivered by SRHs, an increase of 18.7 per cent compared to 2020, and an increase of 29 per cent relative to 2013.

In 2021, there were 311,604 diagnoses of new STIs among England residents, a similar number compared to 2020 (0.5 per cent increase from 309,921) and a decrease of 33.2 per cent since 2019.

The total number of services provided by sexual health services increased by 20.24 per cent. In 2019, SRH delivered over 10.8m services to the public compared with 2013. Latest data shows an alarming increase by 103 per cent in child sexual exploitation cases raised by sexual health services and an extremely worrying 795 per cent increase in domestic violence or abuse cases between 2019 and 2021.

Figure 10

Service transformation is nearing its end

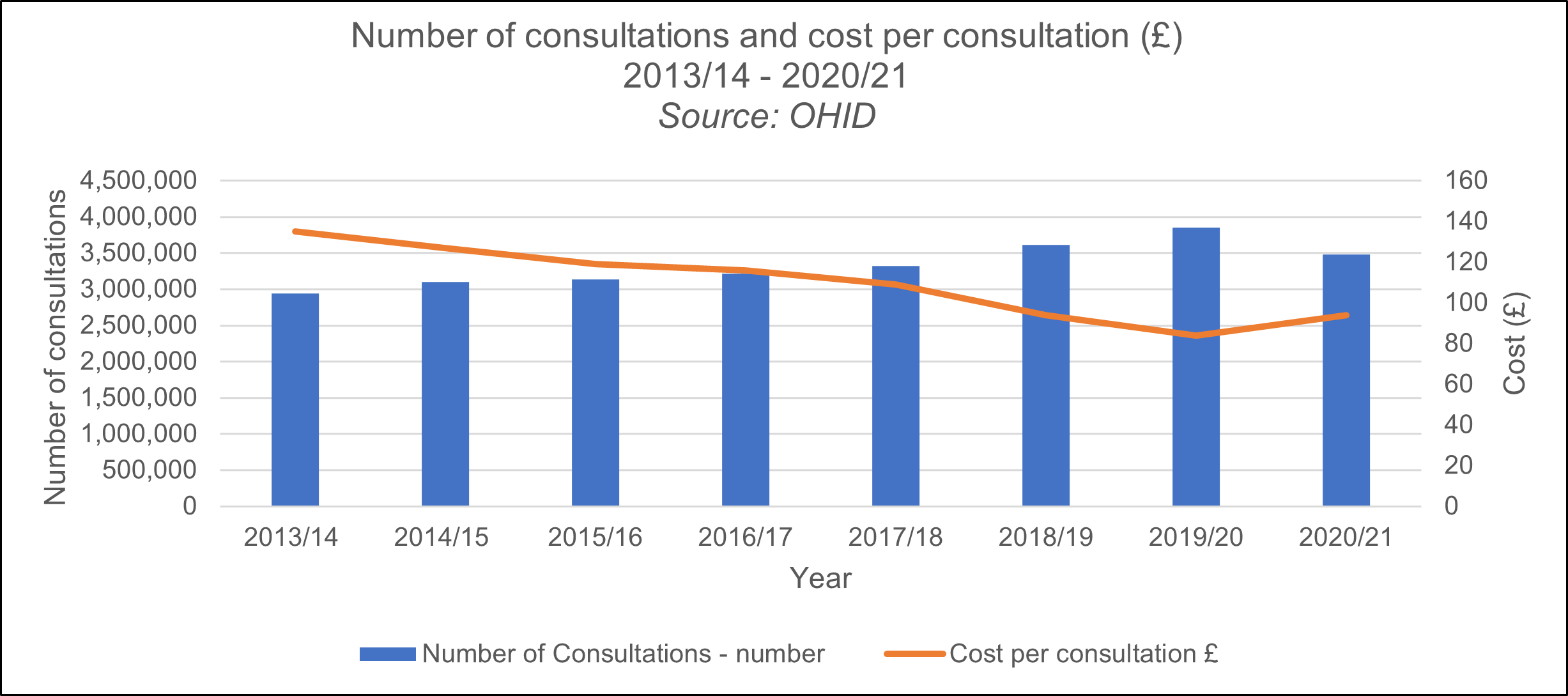

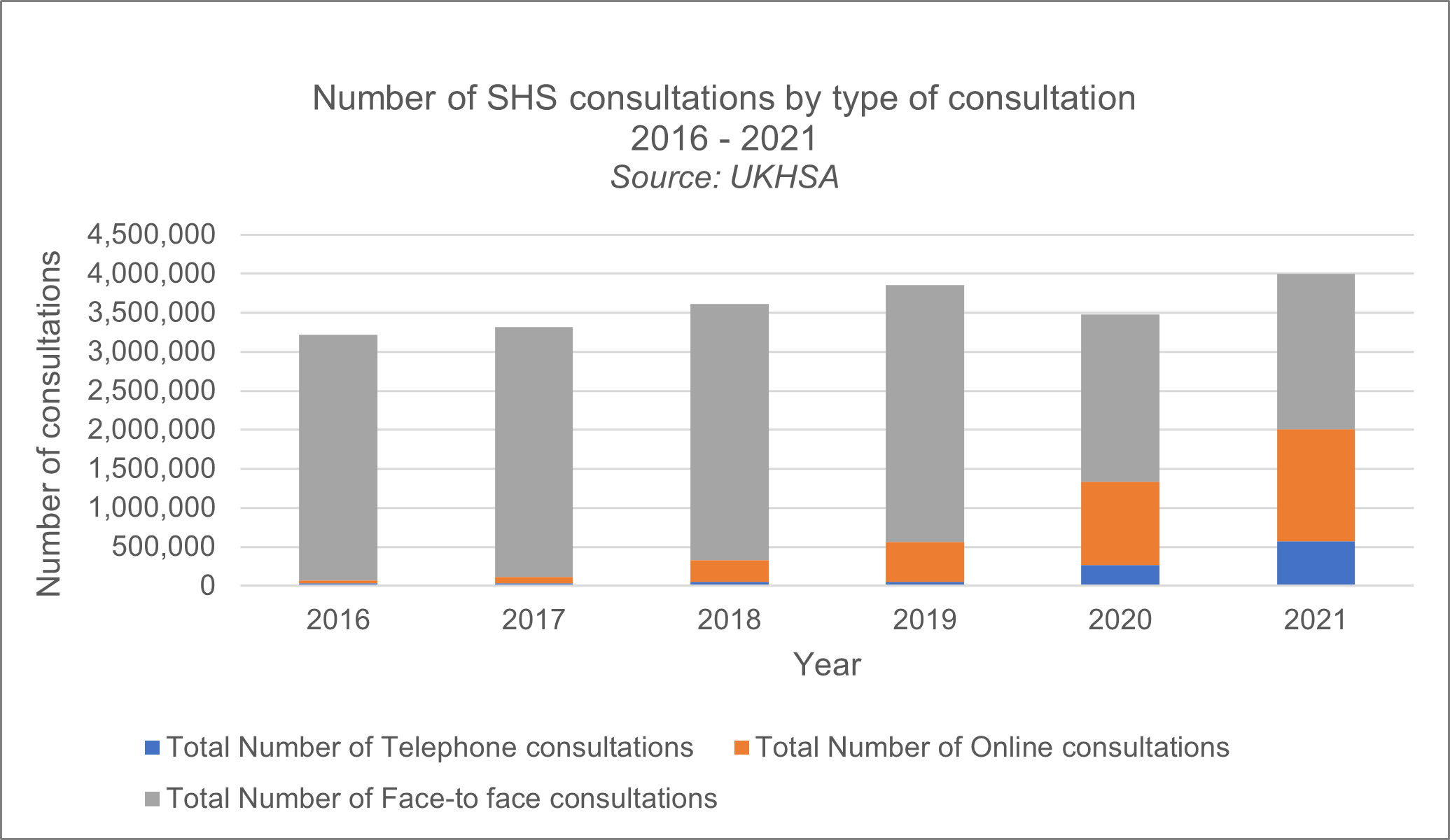

Local councils have been engaged in one of the biggest modernisation exercises in the history of public health, such as a rapid shift to online consultations and home testing and sampling, forced by reductions to the public health grant and local authority funding more generally. However, the ability for local councils to innovate and increase efficiency is nearing its end.

The economic climate and pressure on resources are encouraging everyone to explore new approaches and opportunities that can deliver better outcomes and better value for the taxpayer. Data shows that the average cost £ per consultation has fallen by 30 per cent between 2013 and 2020.

There are examples of councils that have led the way through the creation of strong commissioning networks and expert groups. Contract tenders have been coordinated and best practice shared, ensuring those who need it have access to seamless and coordinated services. Other areas have used the opportunity of being in local government to work proactively with different parts of the system. There are also examples of services that are working alongside drug and alcohol services to provide more coordinated care for vulnerable groups.

Councils, working with their partners, have also been at the forefront of the digital revolution in sexual health services. With the public increasingly using online services to do everything from shopping to banking, it is only right that people can get advice and access testing online.

In response to COVID-19 SRHs continued to diagnose hundreds of thousands of STIs after scaling up telephone and internet consultations, as well as continuing face-to-face appointments. However, it is imperative to recognise that online sexual health services are not a substitute for physical services and should not be treated or relied on as such.

Figure 12

The COVID-19 pandemic has of course had an impact. However, the pandemic also shone a light on the inequalities that are also at the heart of vulnerability to poor sexual health across the country. The full impact of the pandemic on wider public health is yet to be fully understood.

Equitable access to contraception remains a problem

Local councils have been creative and innovative in standing up online oral contraception offers (pills by post) across many areas. In many cases this has been in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, and many have tried to leave these offers in place. However, we are reaching a critical point where local authority provided online contraceptive offers are finding unmet need (as is often the case) and demand in the system without sufficient ongoing resource or co-commissioning with NHS colleagues. Indeed, in some regions/local areas people cannot access online contraception at all due to budget restraint and this is creating inequalities across the country.

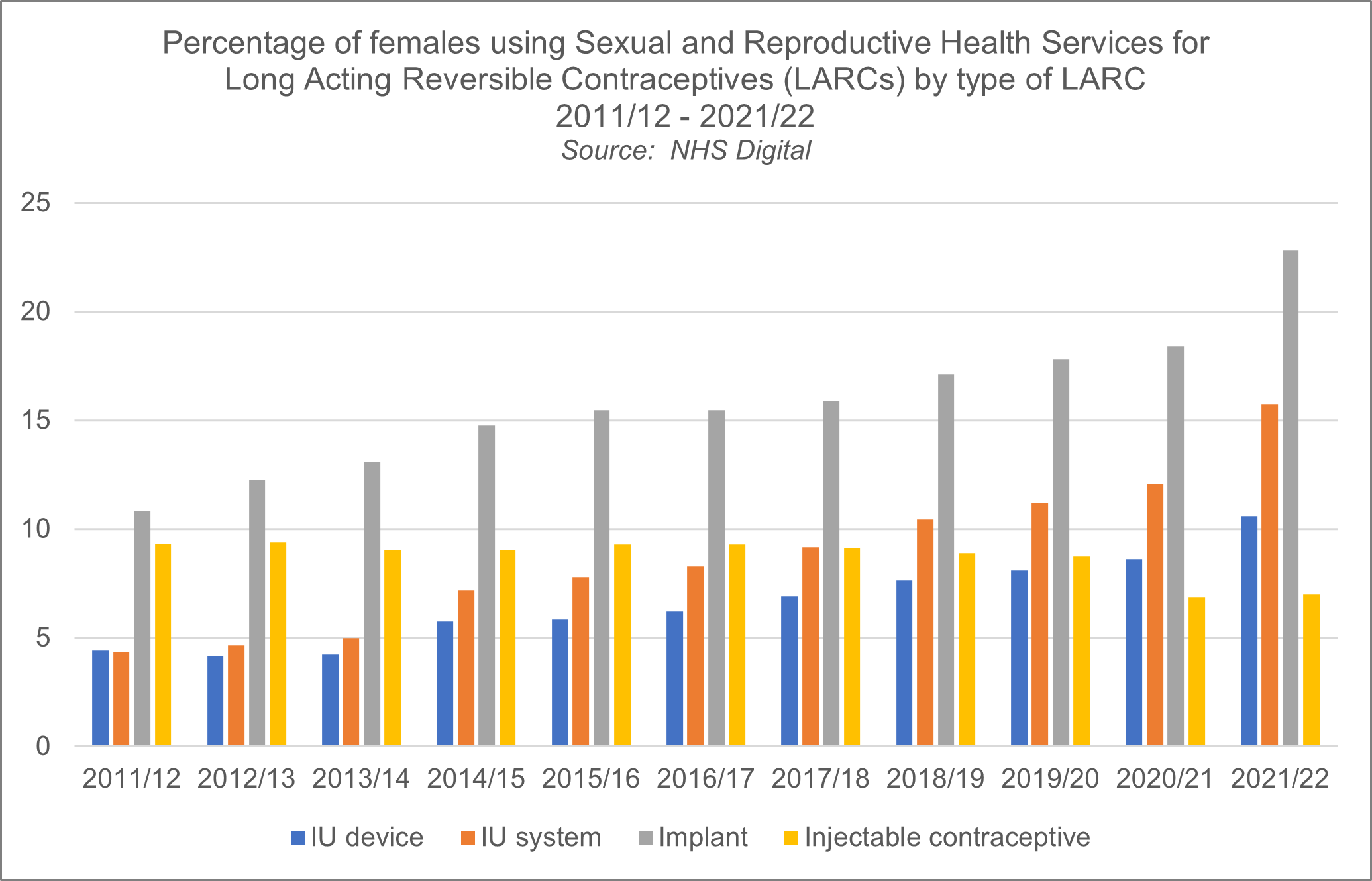

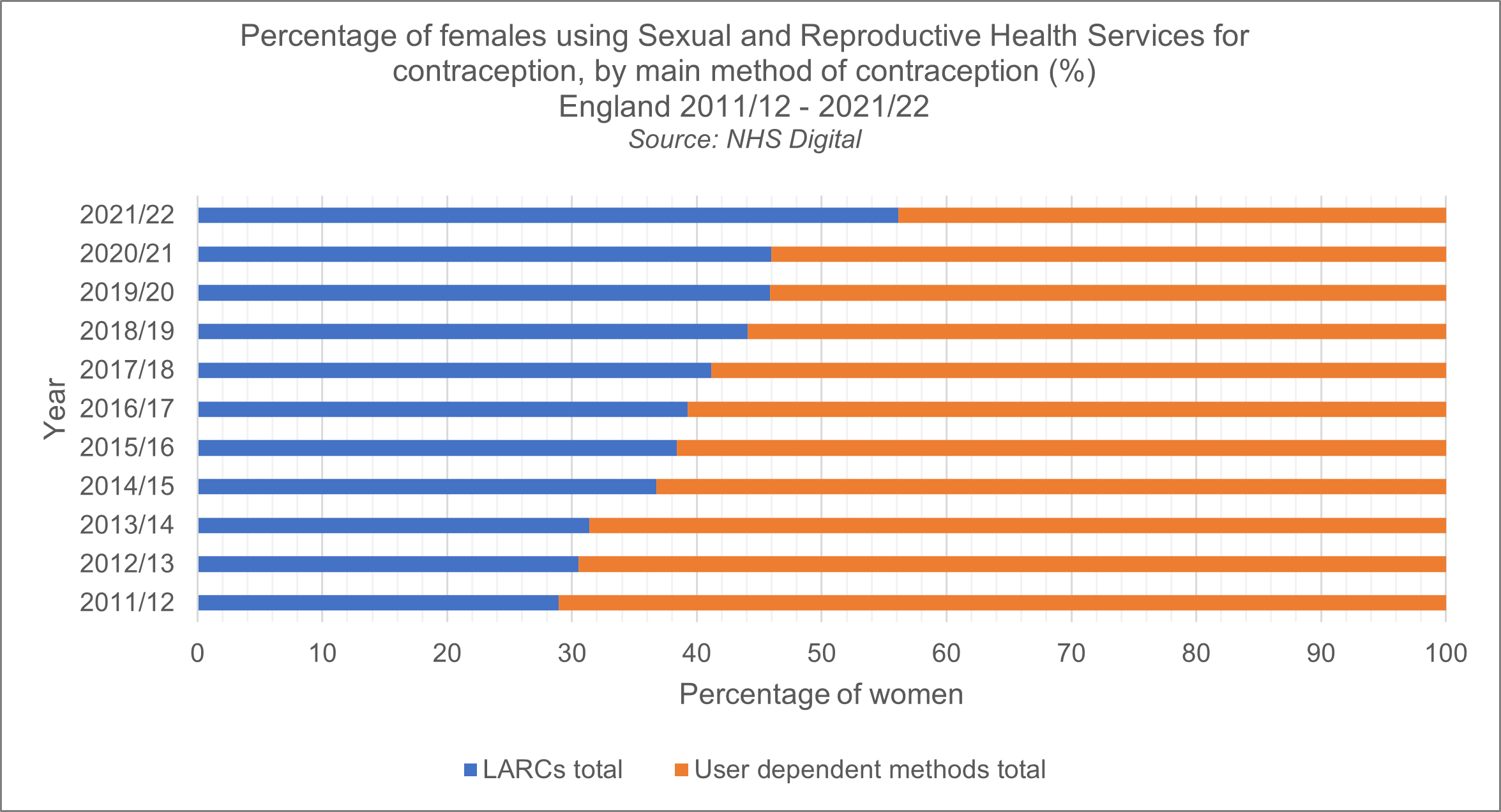

Despite councils best efforts, there are still many existing problems (that were also present pre-COVID) and equitable access to contraception does not exist. Women have been finding it harder and harder to access the contraceptive method they need and there is a clear call and pledge now for systems thinking and collaborative commissioning across to ICS’ to make a difference and improve access. Long-Acting Reversible Contraception (LARC) fittings, and now removals, have been significantly affected as a procedural based service. Marginalised groups have been particularly affected with services reporting a specific drop in access amongst young people, black women as well as women and girls from Asian and ethnic minority groups.

We also know that ongoing difficulties in accessing contraception routinely in maternity has led to increased burden on local authority commissioned provision, particularly LARC, if that offer is not made in the maternity pathway and instead is ‘fast tracked’ to specialist SRH provision in community.

What we want

We are working with public health charities and medical authorities to push the Government to fully fund local authority public health budgets. We want public health, including sexual health services to be fully funded to meet local need.

The recently released Women’s Health Strategy is a positive step in ensuring better access to care for women, with integrated care through examples such as Women’s Health Hubs being suggested as one potential delivery model. The announcement of more NHS investment in ongoing and initiation of routine contraception via pharmacy is welcome news, but there is more to do and local councils have proved that even without the level of funding required, they can be resourceful and innovative and help build a prevention-focused system that empowers people to access what they need, when they need it.

The FSRH Hatfield Vision is also very welcome and represents an appropriate call to action. It aims to ensure that we reduce the currently 45 per cent pregnancies that are unplanned to circa 30 per cent by 2030 for example. It also states that improving access to chosen methods of contraception are vital to the goals set out if we are to truly achieve progress.

This requires more positive investment and collaboration/systems thinking so that we can provide robust and consistent access that is equitable. Indeed, the recent APPG report highlights the real terms decrease in spend on contraceptive services and points to the need for the Government to address this in their forthcoming National Sexual and Reproductive Health (SRH) Action Plan. Further risks and issues highlighted relate to workforce planning and the ongoing risk in relation to the future capacity to fill consultant, doctor and nurse posts across SRH provision.

Sexual Health Services are open access, and we understand that differences in provision should be minimal, so that patients know where to seek services and are less at risk of falling out of the system without receiving the care they need. Pathways for services should reflect the reality of the patient journey so that people are able to seek the treatment and care they need, easily and quickly.

NHSE, ICBs and local councils need to undertake system reviews to ensure that local provision is meeting the needs of local residents. This could be done so that services could be provided over a larger geographical region, more holistically and really utilise the skills, knowledge and experience of clinicians no matter what area they work in, so that we can deliver the best care and services for residents.

There is no time for complacency. Unless greater recognition and funding is given to councils to invest in prevention services, a reversal in the encouraging and continuing fall in some STIs and more unwanted pregnancies is now a real risk. Services will become overwhelmed, health inequalities will remain, and councils may be unable to respond effectively to unforeseen outbreaks such as Monkeypox.

Councils currently face a perfect storm from demand for services continuing to rise just as the price of providing them is also escalating dramatically. This risks hampering council efforts to help support the sexual and reproductive health needs of their populations.

The Government needs to ensure councils have the resources they need to meet these unpredicted costs and protect the services that are helping communities.

Only with adequate long-term funding – to cover increased cost pressures and invest in local services – and the right powers, can councils deliver for our communities, and protect the health and wellbeing of residents.

SRH is not only an important clinical service, it also provides a key public health function, stemming the onward transmission of infections to avoid them spreading among the population. Sexual health involves more than merely educating and informing patients to change their ideas about the prevention and treatment of STIs.

It is vital that we do not see sexual matters as being purely in the realm of the clinician. It is important that approaches are tailored to the needs of different local populations and to the resources available.

We support the need for more joint working between local councils and the NHS to co-commission services for sexual and reproductive health. Integrated care pathways are key, as poorly connected services mean a risk of people falling out of the system without receiving the care they need.

We have come a long way since 1917 but we have much still to do if we are to improve the sexual and reproductive health of the nation.