Executive summary

High quality early years provision can generate sustained and significant improvements on children’s outcomes reducing disparities in later life. Not only does good quality provision have a positive impact on children’s development, it also ensures that parents and carers can feel confident to access childcare. Securing enough high-quality childcare for children to get the places they need is something we need to invest our time and energy into. A mixed early years and childcare market can ensure there is flexibility to meet the needs of children and their families. Local authorities have an essential role in getting this right.

The Chancellor’s announcement in March 2023 of 30 hours of free childcare for every child with working parents aged from nine months to five years means we need to understand what works and what will ensure councils can deliver on their sufficiency duty. Changes to the early years system should not just be seen as quick fixes around the sides, a more holistic view of what works, what would support the workforce, how to ensure there is high quality early education and childcare should be considered.

This report was developed based on a range of discussions with stakeholders across councils to understand what local authorities believe they need to see change so they can effectively deliver on their sufficiency duty for early years education and childcare.

This report explores the challenges in the current system facing local authorities, providers and parents and it looks at what might work going forward. Some of these changes are easier than others, for example, changing some of the existing processes would reduce burdens for providers, local authorities and parents. Others may require longer and more concerted effort looking again at who is eligible for entitlements, how to support the most vulnerable in the system and how children with special educational needs and disabilities are supported across the whole early years system.

Introduction

A child’s earliest years are their foundation; if we give them a great start, they have a much better chance of fulfilling their potential as they grow up. By the time disadvantaged young people sit their GCSEs at age 16 they are, on average, 18.4 months behind their peers and around 40 per cent of that gap has already emerged by age five. Pre-school has almost as much impact on a child’s educational achievement at age 11 as primary school - and the impact is even greater for those who may develop learning difficulties.

This paper explores the challenges within the early years education and childcare system from the perspective of local government recognising the statutory duties for councils to secure early childhood services for families and considers what could be done to improve the system, support the provider market, and ensure good outcomes for children and ensure families have access to affordable childcare. This paper does not explore parental leave policies nor look to cover wider public health services. The recommendations in this paper have been sourced from conversations and roundtables with early years leads in councils, research, and lead members.

While a range of different topics are explored, it is of fundamental importance that any funded offer is sufficiently invested in with a clear plan for workforce recruitment and retention.

Given the announcements in the 2023 Spring Budget, it is even more important that we get the early years system right. The government announced a significant expansion of early years childcare entitlements. This will offer 30 hours of funded childcare for every child of a working parent between nine months and five years with each working parent having an income of under £100,000.

The government also announced a significant additional investment into setting up wraparound childcare for school-aged children with a pledge that families will be able to access childcare between 8am and 6pm during the school day.

| September 2023 |

Increase in 23/24 funding rates. Change in staff-to-child ratios for two year olds, moving from 1:4 to 1:5. Launch of start-up grants for new childminders. |

| April 2024 | 15 hours funded childcare for working parents of two year olds. |

| September 2024 |

New or expanded wraparound provision commences nationally. 15 hours funded childcare for working parents of nine months to primary school age. |

| September 2025 | 30 hours funded childcare for working parents of nine months to primary school age. |

| September 2026 | All schools able to offer 8am-6pm wraparound. |

(Please note funded hours are for 38 weeks of the year)

Council responsibilities

Section 2 of the Childcare Act 2006 identifies early childhood services as early years provision in addition to broader services such as social care and health services, and places duties on upper tier councils in relation to these.

The council must secure ‘early childhood services’ for the benefit of parents, prospective parents and young children, taking ‘reasonable steps’ to involve parents, early years providers and other relevant people in those arrangements. They must also consider the quantity and quality of services, and where in the area they are provided, and consider the views of young children where possible. Councils must also make sure that there is enough childcare available for every eligible two, three and four-year-old to access their free 15 or 30 hours per week. They should also work to identify parents in the area who might not take advantage of early childhood services that could benefit them and their children, and encourage them to take these up. Councils have the responsibility for passing through the entitlement funding for places, calculated by central government, to early years providers. In some places, local authorities have direct responsibility for maintained nursery schools or nursery classes. Further information regarding councils’ responsibilities is available in the LGA’s early years resource pack.

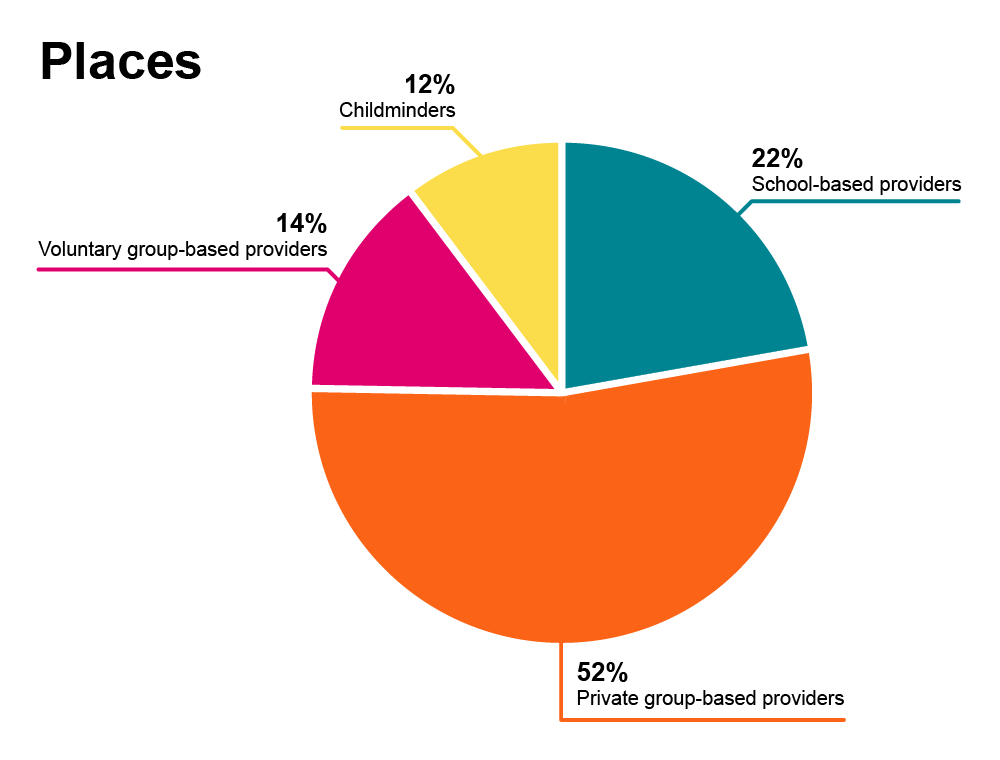

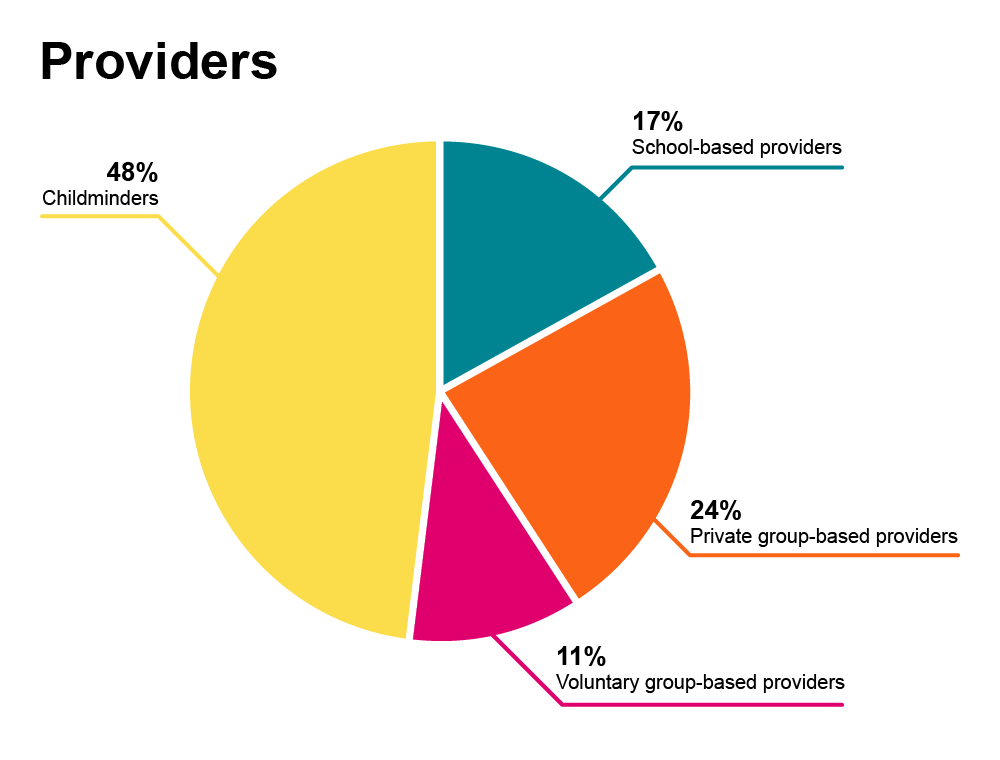

The childcare market

Private and voluntary nurseries account for the majority of early education and childcare places, including around half of free entitlement places. There are currently around 60,000 registered providers and collectively they offer over 1.5 million Ofsted registered childcare places to children aged 0-4. While there are large number of childminders, private and voluntary nurseries deliver the large majority of 0-4 places. Private and voluntary sector nurseries make up just over one third of providers (21,000), yet account for around two thirds of early years places (see Figure 1). According to the Department for Education's childcare and early years provider survey they also account for around half of three and four year old free entitlement places and the vast majority (86 per cent) of funded two-year-old places. However, their presence varies significantly by local authority and by region – from 27 per cent of all providers in the North East to 39 per cent in the South West.

Figure 2: Breakdown of early years providers by provider type

The prominent place of private and voluntary sector nurseries, and their varied presence across localities, is a product of the system’s historical evolution. Until the introduction of the part-time free entitlement offers for three and four year olds, England’s childcare to 0-3s was almost entirely provided through private and voluntary nurseries, play-groups and childminders (with occasional public sector support). Alongside this, some subsidised ‘early education’ in maintained nursery schools and nursery classes existed. Northern local authorities and those in some more disadvantaged urban areas (historically industrialised areas with higher female employment) were more likely to have developed school-based provision. Often private and voluntary sector provision developed better in other areas. Their place was further cemented with the introduction of the universal free entitlement provision from the end of the 1990s.

Although a mixed market provides choice and flexibility to parents, in recent years, local authorities have particularly raised concerns regarding the growth of big chains where councils have limited ability to manage and control them from either undercutting local, well-established provision or growing at an unsustainable rate. Further information is available in the LGA commissioned report on provider openings and closures.

The early years education and childcare system

The now - A convoluted policy direction for early education and childcare

High quality early years provision can have a positive impact on children, particularly disadvantaged children, in terms of their immediate development and long-term outcomes. Research has found that so long as the child attends high quality provision, any drawbacks to being in provision, such as dysregulated emotional behaviour, is unlikely to have a negative effect.

However, above 20 hours in provision, there is no significant benefit to children’s development of attending early education provision, however, if they are in high quality provision, there is no negative effect of being in early education or care for this time. It should be noted that there is a difference between early education, in which providers support children through the Early Years Foundation Stage (EYFS) and childcare, where children are looked after in a safe, supportive environment but where there is no specified curriculum to follow.

The existing system of early years childcare and education is the result of different, disjointed policy announcements made over time with no clear strategic direction. This has led to a convoluted offer where some of the most vulnerable families, who may benefit most from early education and childcare, are left without access to funded entitlements.

It is essential that the early years system enables parents and carers to work. The OBR estimates that by 2027-28 the forthcoming expansion will enable an additional 60,000 people to enter employment and work an average of around 16 hours a week. All of the changes together will result in an impact of 0.2 per cent on GDP. While access to affordable childcare is important for all families, it is particularly crucial for those on the lowest incomes, the most disadvantaged children, women and single-parent families. Childcare enables people to work; increase their hours or take on new opportunities; move out of poverty and improve families’ and children’s long-term life chances.

According to a report by the Sutton Trust on Quality and quantity in early education and childcare, the current system attempts to improve outcomes for children whilst ensuring affordable childcare for parents. While these two objectives do not have to compete, the way the current system is set up means that lower-cost childcare for working parents is prioritised while improving outcomes for children, which requires high quality provision and thus a higher level of funding, has stagnated.

The system crosses different government departments such as the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) and Department for Education (DfE) which contributes to the confused system with inconsistent information being passed to local authorities, providers and families.

The future: Childcare and education – clarity of policy direction

- There needs to be a discussion on the best allocation of public funding to ensure there is mix between early education and childcare and that these two different priorities may require different policy responses to make the best use of funding.

- We should be clear about the motivations for funded entitlements to ensure a system that is equal, supports the most vulnerable and closes the disadvantage gap whilst helping families into work. This is particularly important for support for children with special educational needs and disabilities. The opportunity for children to play in a structured environment and encounter professionals who can ensure they are safeguarded is key.

- Internal government processes should be considered to ensure there is a join up between the priorities across different government departments.

The now: the entitlements offer

Early education and childcare can be most beneficial for children from disadvantaged backgrounds. However, the funded entitlements offer does not provide sufficient coverage for these groups. Indeed, for two-year-old children, there is now likely to be a divide where families who do not qualify for the disadvantaged two-year-old entitlement also do not qualify for the recently expanded entitlements if they are not earning enough to qualify for the expanded offer.

There is a significant inconsistency in the entitlements offer. For example, if one parent earns £101,000 but the other parent is on minimum wage, the family won’t be entitled to free hours. However, if there are two parents that both earn £99,000, they will be entitled to free hours despite having a significantly larger household income.

The current entitlements offer does not include parents and carers who are studying or training, this continues to be the case for the proposed expansion to families of younger children.

The future: the entitlements offer

Review who is entitled to free hours, curbing the more generous offer and ensure that families that are in the bottom third of income distribution do not miss out on this essential support.

At the very least, entitlements should be extended to parents and carers who are in studying and/or training. Entitlements should also be extended to foster carers and kinship carers, regardless of work or training status.

The now: funding

There is evidence from the Early Years Alliance suggesting that the funding for existing entitlements is insufficient, leaving providers to attempt to make up the shortfall, cross-subsidising the ‘free’ hours by charging families significantly more for additional hours or when they do not qualify for free entitlements. On top of this, the recent cost of living challenges, minimum wage increases and inflationary pressures have left early years entitlements funding falling behind the cost of delivery. Prior to the proposed entitlements expansion, this was estimated to be a real terms cut of 9 per cent by 2024/5 compared to 21/22.This leads to instability in the system and higher additional costs for parents and carers. Furthermore, some providers are disincentivised from offering the funded entitlements and thus leaving some families without access to these.

The current model of subsidising funding will also not be sustainable when the expansion to early years entitlements takes place as government funding will cover 80 per cent of the market leaving little room for offering additional hours where further funding could be brought in. Alternatively, providers may choose not to offer the funded entitlements.

The future: funding

An independent review should be undertaken to establish the true cost of delivering early years entitlements in high quality provision, particularly considering the recent government announcement regarding an expansion in entitlements and ensure that this keeps rate with inflation and minimum wage pressures.

The now: the process

There are well-known arguments on the (in)effectiveness of tax-free childcare. It is not always the best form of support for parents, is not accepted by all providers and not all families are aware it is available. Furthermore, there has been an underspend in the budget for tax-free childcare each year since 2017 which has not been reallocated to supporting early years education and childcare more broadly.

The process for entitlements must be reviewed. Currently, families face a delay between their initial sign-up for free hours and when they can take up that place. Families are also expected to re-confirm their eligibility for free entitlements every three months and it is not clear why this level of quarterly assurance is necessary. This puts significant pressure on families, providers and local authorities to support families to do this or can leave children and their families without childcare at short notice, impacting their ability to work and the child’s stability. Conversations with local authorities suggest that any impact on fraud is likely to be low as families do not tend to fall in and out of eligibility at a rate that would result in fraud being a concern. Given the pressures that families are under, the removal of this pressure is likely to have significant benefits.

The future: the process

Review tax-free childcare to ensure it is delivering on its objectives, providing value for money and explore if the funding can be used more effectively through an alternative route. Remove the one-term delay to taking up entitlements.

Families should only have to re-confirm their eligibility for free entitlements once a year, instead of termly. Streamline entitlement applications that link with additional funding such as disability access fund and early years pupil premium data and establish one place to check eligibility and automatic checks for additional funding for EYPP.

The now: the market

As noted above, the childcare market is mixed with private, voluntary and independent nurseries, maintained nursery settings, school-based provision, and childminders. A core premise of the early years market is to ensure parents have choice. However, too often we hear that families who work a-typical hours, live in rural areas or who have children with special educational needs and disabilities struggle to access provision.

Furthermore, some providers are not offering free entitlements to families in part due to the fact the funding does not sufficiently cover the cost of delivery of places.

This suggests the market is not working as it should, parents and carers do not have the choices they should, given the focus on parental choice. Further information regarding the situation in the PVI market is available in the LGA commissioned report on provider openings and closures.

Maintained nursery school (MNS) provision is inconsistent across the country. MNS offer essential support to children, particularly those with additional needs or from more deprived backgrounds. In addition, they act as areas of support to other local provision. Although the announcement of some additional funding for MNS is welcome, the ongoing uncertainty regarding the government’s policy direction on the childcare market results in instability in the system.

The number of childminders have declined by nearly 50 per cent since 2012. There are a range of reasons for this, including, inflexibility in the regulations for childminders, high levels of paper work and admin, and limited support in their role. Childminders have a key role in ensuring flexibility for parents and carers.

Local authorities are starting to raise concerns regarding the growth of private equity in the early years market. Although the impact on quality and children’s outcomes is not yet clear, the financial situation sitting behind these providers that can be indebted and have complex financial structures is a concern in an already unstable market. Furthermore, there is some evidence in a publication on financialisation and private equity in early childhood care and education in England, that pay is not prioritised in for-profit organisations.

The future: the market

Government should work with councils and wider stakeholders to develop a clear strategy for what the childcare and early education provider market should look like in the long term with clarity surrounding the role of the private and voluntary sector, maintained nursery provision and school-based provision alongside wider community groups.

Within each local area (at a level that is reflective of the local population size) there should be an ‘expert’ provider, this can be either maintained, PVI or school-based provision. This provider would be given additional funding, through the local authority, to support staff development, provide concerted support to some children and families, alongside the local authority, and have intense wraparound support from other services such as speech and language therapists, SENCOs and family support workers. Dependent on the size of the local area, a hub and spoke model could be explored to ensure equitable access. The status of these expert providers would need to be underpinned by a clear framework setting out responsibilities of different partners.

Childminders need support to reduce the financial and regulatory burdens they experience. The opportunities for councils to develop childminder agencies or provide different ways to support childminders should be explored.

A long term commitment to maintained nursery settings is required supported by ongoing funding that recognises the potential greater costs of delivering maintained provision. MNS could have a clear role as system leaders with ongoing funding.

We need greater oversight of financial risk in larger providers. The market should not rely on private equity to expand the childcare sector and careful monitoring of these providers should take place.

The now: workforce

A highly qualified workforce is one of the main factors in ensuring a quality early education and childcare offer which can have a long term positive impact on children, improving their outcomes later in life.

Workforce recruitment and retention has long been a concern for the early years sector however it appears to have reached a tipping point with increasing numbers of providers struggling to recruit properly qualified staff.

The workforce is considered to be, on the whole, underpaid and undervalued, with anecdotal reports of practitioners leaving the sector to work in other sectors such as retail which offer higher rates of pay with less responsibility. The qualification and training system is complex with fewer people coming through the system to take up roles.

The requirement for Maths and English qualifications to study for the level three early years educator qualifications since 2014 concerns some local authority leads, with the suggestion that not enough focus is placed on empathy or skills in working with children. Furthermore, there are numerous training providers which makes it difficult to navigate who is offering high-quality training and who is not.

Children learn through play and learn from the adults around them, so even when formal learning is not perceived to have taken place, it is an essential element of the early years offer. Councils feel they battle to ensure that early years providers are seen as educators as well as caregivers.

The Government’s proposals to change the ratios between staff and two-year-old pupils, from 1.4 to 1.5, will not address the structural challenges within the childcare system. Councils share the concerns of early years providers that the change will not result in any meaningful savings for settings or lower costs for parents, whilst increasing difficulties for providers. This is because providers may choose to work within the current ratios which increases the amount of adult interaction with children, prioritising their needs. This is even more important for children with additional needs who may require additional support. There is a risk that the expectation of lower costs could result in disquiet between providers and parents increasing pressure on the workforce. Alternately, if funding is not sufficient, providers may be forced to work in the lower ratios which may affect care.

The future: workforce

The Government should work with the sector to develop an effective workforce strategy focused on drawing people into the sector, and their ongoing development and training, recognising the benefit early years educators can bring to young children. This strategy should include childminders.

Explore how both people who are in ‘early’ in their career and ‘later’ in their career could be supported to train to be part of the early years workforce. Review existing training and qualification processes across the early years sector, both to enable increased staff training into the system and ongoing development and training.

Evidence from the Low Pay Commission and the DfE Survey of Childcare and Early Years Providers Survey found that for private providers, 15 per cent of staff aged 25 and over were earning below the National Living Wage, and 13 per cent for voluntary providers. There should be a greater grip on those providers that are not currently paying their staff minimum wage and a clear analysis as to why this is.

Explore the creation of "training settings". This means enhanced funding could be allocated to particular providers which allows for more staff to be trained in the workplace, linking to apprenticeship and other training programmes. This would need to work closely with training providers, including further education colleges, and nursery chains, schools and MATs. Family Hubs could also provide an important role here, delivering training on site and providing support with practitioner’s own childcare and qualifications.

Support the national roll out of inclusion training to support staff to understand how to support children with special educational needs and disabilities.

Accompanying the review of funding for early years education and childcare, there should be a review the pay of ECEC staff. A payscale for staff, like that in Ireland, could be explored if it is sufficiently funded.

Support staff to have capacity to undertake training, for example, by ensuring training days are funded like schools with inset days.

Reverse the proposal regarding the ratio change, taking account of its impact on staff wellbeing and child safety. Explore flexible working for the workforce, learning from other frontline sectors.

The now: support for vulnerable/disadvantaged children

Although it is challenging to directly compare with previous years given changes to the Early Years Foundation Stage (EYFS) framework, there has been a decline in the proportion of all children reaching a good level of development in 2022 at 65.2 per cent. This has declined since 2019 when it was 71.8 per cent. In areas such as Middlesborough the proportion of children reaching a good level of development is lower than in more affluent areas, such as Surrey. However, children eligible for free school meals have poorer educational outcomes in schools in affluent areas compared with their peers in more deprived local authorities.

The impact of Covid-19 and a new form of assessment has likely contributed to this fall, however, there is still significant disparity among children. The educational outcome gap between children on free school meals and those in the early years foundation stage who are not was 19.6 percentage points in 2022.

The impact of the pandemic, alongside the rising cost of living and a reduction in wider support for children and their families from other community services, such as children’s centres, has led to concerns about a growing disadvantage gap, reduced school readiness, and increasing presentation of children requiring additional support in early years and school settings, including special educational needs and disabilities.

Care for children with special educational needs and disabilities can be more expensive due to practical changes that need to be made to provision, or due to an increased ratio of staff to child.

The Special Educational Needs Inclusion Fund (SENIF) and the Disability Access Fund (DAF) are the two main routes to support early years providers to support children with SEND. However, LGA commissioned research highlighted a range of challenges with funds, including limited take up and barriers within the process with data not being shared across the system.

The number of children who take up their funded hours for disadvantaged 2-year-old entitlements can be low, although according to statistics it has been improving in recent years. In addition, there has been a further decrease in the eligible population as the fall in parents of 2-year-olds receiving legacy benefits, which Universal Credit has replaced, hasn't been offset by the rise in those receiving Universal Credit. The benefit thresholds have been frozen in cash terms since before the introduction of universal credit, meaning that they have become less generous over time as wages have risen. As a result, between 2020 and 2022, the number eligible for the entitlement has decreased.

The future: Support for vulnerable/disadvantaged children

It is essential to ensure good quality provision supports children from disadvantaged backgrounds and with special educational needs. This could be by enhancing the join up between different providers and using some providers as teaching or support organisations. This should be done in partnership with the local authority who will recognise the types of support required and provide join up with other parts of the system, such as children’s centres or family hubs.

Information flow from central government should be improved to identify children that may need some additional support. For example, giving local authorities the data for the children who qualify for the Disability Access Fund (DAF).

Also needed to support vulnerable/disadvantaged children:

- Improvement to the system surrounding the Disability Access Fund, Special Educational Needs Inclusion Fund and Early Years Pupil Premium.

- Ring-fence SENIF to support a focus on take-up.

- Standardising SENIF eligibility criteria and funding levels across LA areas to create greater consistency across the England.

- Align the DAF with DLA to remove the need for parental application.

- The Department for Education should provide LAs with EYPP eligibility lists, as they do for eligible two-year-olds.

- Give local authorities greater responsibility and resources for annual monitoring on how EYPP funding is used to ensure it is being spent as designated.

- Increase the early years pupil premium rate to be the same as the pupil premium rate for school-aged children.

- Increase the maximum income threshold rate for disadvantaged two year old entitlements.

Children who attend PVI provision do not get access to free school meals [as they do in maintained nurseries and school-based provision if attending before and after lunch], despite this being the only choice for some families locally. There should be greater equality in access to ensure all vulnerable families get the support they need.

The now: clearer guidance for providers

The current guidance for providers is complex particularly surrounding additional charging, for example, for consumables. The guidance is viewed and applied inconsistently, making it challenging for local authorities to effectively challenge without driving providers out of the market.

An additional challenge is the availability of funded places where some providers can limit the number of funded places or require additional hours to be attended by children which can result in confusion and further costs for parents.

Charging can also take place around the current funded offer for vulnerable two year olds which can add unexpected costs to disadvantaged families.

The future: clearer, stronger guidance for providers

To receive public funding, there should be an expectation on providers to support children with special educational needs and disabilities, and children from more deprived backgrounds. Ofsted should have a role in ensuring that there is high quality SEND provision available in settings.

The guidance regarding charges outside of the funded entitlements is complex and it can make it challenging for local authorities to give providers appropriate support whilst ensuring they are sticking to their statutory duty. The guidance requires clarification particularly in relation to consumables, charging, funded places allocation.

There should be greater clarity in invoices so parents can be better aware of what they are being charged for, and councils can ensure providers are implementing the guidance appropriately.

There should be a clear expectation set out by the government that providers should work closely with councils when setting up, managing and closing provision to support councils to fulfil their sufficiency duty well.

What should the wider system do?

Family hubs and children’s centres

There is an opportunity to bring about new ways of working within the sector, supporting early years providers and other partners to work closely to together.

Build on the effective approach to integrated reviews, bringing together different partners to provide a holistic view of the child. This approach recognises that a range of professionals have unique perspectives on a child and family which can result in a more effective assessment of their progress.

The Government should coordinate the development of a cross-Whitehall ambition for children and young people, clearly articulating the role that all departments will play.

With the development of family hubs and the best start for life there is the opportunity to maximise the offer that is available for families. With differing direction from central government asking councils to develop different web pages and production of information it is unhelpful and does not allow the opportunity for councils to respond to the ways that families require and use information. There should be more local flexibility in implementing national programmes, alongside a more coordinated approach from central government.

Councils should explore the links between wider community facilities, such as libraries, and their role in supporting early years children and families

Improve commissioning relationships with health services so families and providers can get the support that they need, particularly for children with SEND.

The move to place-based delivery through ICS and ICBs is likely to help this but delivering for children needs to be core within ICB strategies.

Support for children with SEND

Bringing together different parts of the system means there is the opportunity to provide greater support to children with SEND. For example, health visitors, SENCOs and speech and language therapists working more closely with providers. This requires investment in the workforce in other parts of the system.

Conclusion

The recommendations laid out above cover a range of areas that include understanding more about the current problems and what would work to tackle them, investing into a sustainable system that supports the most vulnerable children and families and reforming the current system to make it easier to implement for councils and providers, and for families to understand.