Introduction

The annual budget process is probably the single biggest, most complex exercise that any council undertakes as part of its annual cycle. Many councils start the exercise almost as soon as the previous year’s budget is agreed and the process takes almost the whole year, involving every elected member at some stage and a considerable cast of senior officers as well as partner organisations.

Getting this process right is vital to the council’s success and contributes significantly to what it achieves for the local area. Without a sustainable budget which supports long-term financial resilience many other plans and aspirations may well founder.

This guide draws on experience and good practice to set out some pointers for a good, effective budget process. It is aimed primarily at senior leaders – council leaders, mayors and chief executives – but may also prove valuable to a wider audience.

For simplicity, the guide refers principally to the general fund revenue budget, which results in the annual setting of council tax. This budget is usually the most complex and often the most politically contentious. But many of the ideas and principles set out here have wider application.

Councils should not ignore the importance of budgeting for the housing revenue account (HRA) or for schools funded by government grant, for example. In particular the capital budget (‘capital programme’) commits the council for many years ahead and should receive appropriate attention from senior leaders.

This guidance is aimed largely at principal authorities. The LGA is undertaking separate work with combined authorities to capture good practice in financial management, including budgeting.

Above all councils should use whatever budget process works for them. This guidance is based on a commonly used approach but discusses the pros and cons of other approaches. Care should be taken in switching from one approach to another that the new approach will deliver a sustainable and resilient outcome.

Links to wider plans

Although the annual budget process is a complex exercise, it does not stand alone among the council’s plans and strategies.

The annual budget should be seen as the yearly allocation of financial resources towards the achievement of the corporate plan, and the next stage of a longer-term financial strategy.

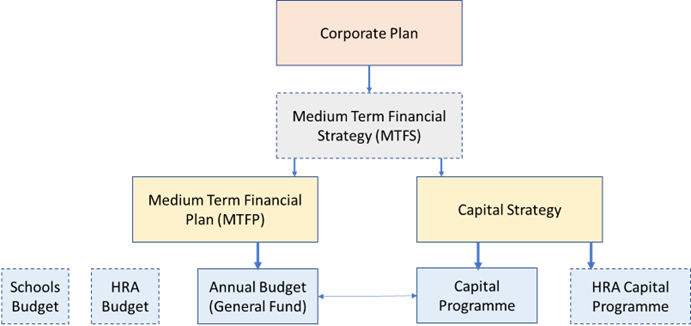

Figure 1 shows the documents you might see in a typical financial planning structure, although the names and content of individual pieces can vary. Not shown on the diagram, for simplicity, are the many service, programme and project plans which also form part of the overall framework.

All these documents must be consistent with each other and contribute together to the achievement of the corporate plan. This is therefore one of the key tests for the annual budget process.

Together these documents form the main parts of the budget and policy framework which has a special constitutional status. As one council’s website puts it:

The full council has responsibility for setting what is called the policy and budget framework. This is a collection of plans, strategies and policies (including the council's budget) which describe how services are to be provided. The cabinet and individual cabinet councillors can make policy but only within the framework. Cabinet can make recommendations to council about any policy change which is outside the existing framework.

(Source: Bath & North East Somerset Council)

A key point here is that the setting of the budget and the policy framework underlying it are matters that are reserved to the full council. This means there will always need to be a meeting of the council to set the budget. These arrangements may differ slightly according in the council’s local constitutional arrangements, but the principle that full council sets the strategic direction and the budget applies across local government.

Fig. 1 A typical financial planning structure

Not all councils will have the same structure or naming conventions, but the diagram illustrates the relationship between the annual budget and the corporate plan, normally via a medium- term financial plan (MTFP) and sometimes also a medium-term financial (MTFS), which is more likely to have a narrative style and may in practice be incorporated in the corporate plan. In practice the terms MTFP and MTFS are often used interchangeably. The annual revenue budget will be related to the capital programme via the MTFS/ MTFP and a capital strategy. There is also a requirement to produce an annual treasury management strategy which links the cash requirements of the revenue and capital budgets (not shown in the diagram) and crucially sets the limits on borrowing.

The corporate plan

The corporate plan is the pre-eminent planning document for the council, setting out how the administration’s priority outcomes for the area will be realised and drawing on the administration party’s manifesto or any coalition agreement that might be in place. It is agreed by the full council.

Some councils choose to present the annual budget to council at the same time as an annual review of the corporate plan and this is one way of ensuring that the two remain aligned. Of course, the ambition expressed in the corporate plan may need to be tempered by financial realities, so just as the corporate plan should inform the medium-term financial plan and annual budget, the corporate plan may need to be flexed and informed by financial planning.

This points to the annual budget being an important corporate exercise that needs to consider issues beyond the purely financial. This issue is discussed further below.

The medium-term financial plan or strategy (MTFP or MTFS)

It is essential that the annual budget is part of a longer-term forecast, normally covering at least three to five years ahead. There is essentially little difference in practice between an MTFP and an MTFS and councils use the terms interchangeably. An MTFS tends to contain more of a narrative element and links the financial plans more explicitly to the corporate plan. In this document, for simplicity, we will use the term ‘MTFP’ to describe the medium financial strategy and plan.

Once again, this discussion focuses on the revenue budget, but a full MTFP or MTFS should comprise revenue and capital plans for all services and should also include treasury management indicators and forecasts to ensure consistency across all financial policies.

Longer term planning is challenging given some of the uncertainties that affect councils including, for example:

- One year grant allocations and financial settlements for local government

- Economic turbulence, including inflation and the risk of recession

- Uncertainties of the legislative timetable

- The costs of unforeseen local, national and global events.

For this reason, some councils do not take the MTFP particularly seriously. They reason that many of the forecast numbers are so uncertain that the MTFP is of little value. Hence it is not uncommon to find that many MTFP statements appear to be incomplete, with key numbers not forecast forward beyond a year or two.

But this is the wrong view to take. The need to plot a course through uncertainty begs for more, better planning rather than a short-term outlook and the MTFP, while it will need to flex as circumstances change, is the basis for planning.

For this reason, many councils consider their MTFP to be a financial forecasting model to inform planning rather than a plan in its own right.

At the very least, a forward-looking financial model of the council is required against which to measure uncertainty and make decisions. There is some evidence that councils that have got into trouble financially have tended to find it difficult to look beyond the next financial year – which in turn may make it seem easier to avoid difficult decisions at the point they ought to be taken.

Whatever form the MTFP takes, it is important to realise that financial forecasts are always uncertain, even in a stable environment, and that the assumptions built into an MTFP therefore need to be understood and revisited regularly. The section below on forecasting and scenario planning goes into more detail on planning assumptions.

The typical period covered by an MTFP is three to five years, but a four-year plan can be sure to cover the electoral cycle, including at least one election year (when the politics of the budget is naturally more contentious) and, for councils elected by thirds, at least one ‘fallow’ year. A council that is forward planning effectively will legitimately look at key milestones in the electoral cycle to identify where key decisions might need to be made, or where politics may make the budget process more difficult. Three years is the bare minimum a council should consider for its MTFP.

is the summary budget table from a council’s MTFP showing projections for budget growth and funding. Invariably, as in this case, the MTFP may include a balancing ‘budget gap’ which is, in effect, the savings target that the council will need to achieve to balance the budget. Ideally it should be the aim to close the budget gap for several years ahead. This has become much more difficult in practice (although not impossible) because one of the effects of austerity and uncertainty is to make a balanced forward position harder to achieve, but it is a realistic goal which some councils achieve. .Fig 2

We go on to consider the savings target in greater detail below.

Fig 2: A typical summary Medium Term Financial Plan

| 2023/24 | 2024/25 | 2025/26 | 2026/27 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| £m | £m | £m | £m | |

| Budget Requirement B/F |

198,930 |

201,178 |

206,719 |

210,983 |

| Inflation |

8,505 |

3,557 |

3,557 |

3,626 |

| Growth |

3,000 |

4,000 |

8,000 |

4,000 |

| Savings |

(0.256) |

0.000 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

| Reserves |

(1.091) |

0.000 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

| Forecast Council Budget Requirement |

209,088 |

208,735 |

218,256 |

218,609 |

| Funding: | ||||

| Council Tax |

115,795 |

118,702 |

121,681 |

124,735 |

| Business Rates and RSG |

42,487 |

43,337 |

44,204 |

45,088 |

| Collection Fund Deficit |

(1.376) |

0.000 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

| Grants |

44,272 |

44,680 |

45,098 |

45,522 |

| Forecast Funding |

201,178 |

206,719 |

210,983 |

215,345 |

| Remaining Budget Cap |

7,909 |

8,016 |

7,273 |

3,264 |

| Cumulative Budget Cap |

7,909 |

9,925 |

17,198 |

20,462 |

The capital strategy and capital programme

This ‘Must Know’ guide is not about capital planning, but the revenue budget does need to reflect the council’s capital plans.

Capital planning is in many ways very different from revenue budgeting because it involves making decisions that will affect the council for many years ahead. For some services (such as highways and housing) capital investment is just as important if not more important than revenue.

The term ‘capital investment’ has recently acquired a narrow meaning relating to commercial property, but all capital spending is investment in the widest sense of putting money in now to benefit the future. Capital planning requires senior leaders to see themselves as custodians of the future. It is easy to see how such considerations can be de-prioritised in the midst of a difficult set of short-term budget decisions.

The ’capital strategy’ is therefore important because its role is to identify the council’s need for capital investment (such things as where and when new schools might need to be built) and its priorities. The housing revenue account is required to have a capital strategy covering the next thirty years. For other services looking further ahead than the period of the MTFP would seem appropriate. The ‘capital programme’ is then the detailed list of schemes that will be started or continuing during the period of the MTFP.

The Prudential Code for Capital Finance which originated with the Local Government Act of 2003, enables councils to decide locally the balance bw3teen their revenue and capital spending (at the time of writing in 2023, the government is considering introducing additional controls on borrowing). Councils can borrow affordably, but affordability means the capacity to carve out sufficient funding within revenue budgets to pay for the borrowing. As a rule of thumb, more borrowing means less funding for revenue services. Rising interest rates and capital budget inflation have made capital spending financed by borrowing less affordable in recent times.

In practice, revenue and capital planning must therefore work in parallel and the MTFP and annual revenue budget must include funding for the revenue implications of capital spending.

- Where capital expenditure is financed by borrowing, for example, the revenue budget will need to provide for debt interest and also statutory provisions for repayment, known as “MRP” (Minimum Revenue Provision) in accordance with separate regulations and guidance.

- Where capital expenditure is financed from capital receipts or reserves, this may involve spending money that has been invested for a return, so the revenue budget needs to reflect reduced investment income.

- Capital spending may also generate additional running costs for new buildings and facilities which also need to be budgeted for.

Finally, there is a relationship between revenue and capital spending which needs to be taken into account in budget decision-making. For example, there is a relationship between capital investment in buildings and future maintenance budgets. It is a common strategy to save money in the short term by cutting back on maintenance of buildings, but this increases the likelihood that major refurbishment may be required in the future.

Objectives of the budget process

It is a legal requirement for a council to set an annual budget and for that budget to be ‘balanced’ or fully funded. As far as the revenue budget is concerned, the main requirement is in the Local Government Finance Act 1992 which sets out procedures for setting a council tax.

There should be no doubt that budgeting is also good practice. In the commercial world, there has been an ongoing debate over whether budgeting is even necessary. In commerce, if an organisation understands its costs then it knows how much it needs to sell to make a profit, so it may make more sense to manage on sales targets than on budgets.

In the public sector, however, it is important that the allocation of resources between policy objectives is planned and the use of public funds is controlled. From this essential requirement for budgets in the public sector flows other uses for the budget, such as holding service managers responsible for their spending.

For councils, the budget is not just a planning device but also a public document and decision-making about the budget needs to be transparent.

A budget is a model of the world in which the council operates. It is version of the truth. If a budget departs from reality (e.g. by expecting service delivery standards that cannot be met within the funding envelope) it ceases to have any value. The budget is a basis for public debate about the adequacy of resources and the determination of priorities.

There are many reasons why councils need to set an annual budget, but the overriding objectives in doing so are to ensure that the council's financial plans are both sustainable and resilient.

Financial sustainability means that income = expenditure over the cycle.

Financial resilience means the budget provides for risks and uncertainties, enabling business continuity into the long-term future, including dealing with unforeseen eventualities.

Financial sustainability ensures that as much as possible the council can continue to deliver services and other benefits for the local area and a commitment to financial resilience ensures that it can do this in an uncertain world in which events may happen which cost the council more or financial parameters may change. The need for financial resilience requires the keeping of reserves.

The budget process can be seen from three perspectives, each of which is vital to producing an effective budget. This reflects that the budget is, at the same time, a financial plan, a management tool and last but not least, a political expression of priorities through the allocation of resources.

The budget process is thus…

| A financial process |

The budget must add up, make sense from a financial point of view and include the ‘right’ figures. It must also provide adequately for risk. The chief finance officer and their staff will be central to ensuring that the budget meets these criteria. |

| A management process |

The budget needs to be deliverable and compatible with the service delivery levels and performance standards the council sets. As such it need to have buy-in of service managers. The budget is also used as a performance management tool, with the effectiveness of managers being judged on whether they deliver within budget. Service directors and budget managers therefore need to be involved in budget setting. |

| A political process |

The budget needs to be consistent with the policy priorities of elected members and deliver clear policy outcomes. The process needs to enable difficult decisions about priorities and be clear about trade-offs. It also needs to enable the annual setting of the council tax. Under the leadership of the leader/mayor and the cabinet or committee chairs, all elected members will therefore be involved at some stage, as will the chief executive and the council’s policy staff. |

The budget needs to meet all the usual compliance requirements for any major council decision, which involves another cohort of council staff and other stakeholders. This includes for example, communications staff, equalities and scrutiny teams. Council suppliers and strategic partner organisations might need to be engaged. Not involving partners runs the risk that implications may not be identified as part of the budget process, or that stakeholders will not be bought in and will be reluctant to co-operate.

From this it follows that the annual budget process needs to be a highly collaborative process between members, the corporate management team and a wide cohort of officers.

Circumstances will vary in different councils. Where key services are outsourced, providers may need to be part of the conversation. Where the council is in no overall control, opposing parties are more likely to have an earlier role.

Although the budget process is best led by the leader/mayor and the chief executive, it is possible for the initiative to come from elsewhere. It is not uncommon to find councils where the budget process is steered largely by the chief finance officer. This can work well it doesn’t lead to the budget being seen as a purely technical, financial exercise.

If the budget is led by officers, it may not produce the policy outcomes that members want from it. One impact of austerity has perhaps been to make the budget more of an officer-led exercise, in which members’ aspirations seem permanently frustrated by lack of resources, but there are obvious dangers in this, not least that it is the role and responsibility of members to decide where priorities lie and where savings should be made.

In fact, if a council leaves the budget process to any group (members, managers or the finance team), without engaging effectively with the others, the budget is likely to lack something. For example, it may lack credibility with the service directors and managers charged with delivering it, with the result that it doesn’t get delivered.

A budget process which does not engage effectively with the full range of members, officers and stakeholders is less likely to be sustainable and resilient.

Officer and member roles

The budget process will involve a wide range of stakeholders, but the final decision is one that is reserved to full council. The stakes are often high, both in political and organisational terms, and it is not uncommon for members and senior officers to have full and frank discussions over the outcome. The decision-making follows the pattern adopted across the whole of local government:

- elected members set the policy and strategy for the council within a common law and statutory framework and

- officers advise and deliver and mediate to facilitate member decision-making if necessary.

When acting within the law, members have discretion not to follow officers’ advice but must take it into account and weigh the consequences of not following professional guidance. As described later in this guide, officers have certain duties to report publicly on the setting of a lawful and balanced budget.

To facilitate the implementation of the budget, full council normally delegates powers to the executive/ committees or to officers, including power to vary the budget up to certain limits.

Those with experience will quickly realise that the budget process in practice encounters many issues along the way. In driving forward the budget process, and keeping all stakeholders focused and on board, skilled leadership is required, recognising the human aspect when people with different viewpoints are asked to collaborate in a complex and difficult process in which no one is likely to get what they would ideally want.

Planning the budget process

A complicated process over a long period of months with many participants calls for careful planning. Add in the political aspect – that the budget may also be contested and controversial- and a detailed timetable is required to ensure that the budget process meets its objectives.

The first task of the budget process is therefore to prepare a timetable, usually an update of a process that has worked successfully in the past.

The timetable is a matter for discussion between the council’s political leadership (including scrutiny chairs) and the officers steering the process since it will set out in practice when decisions need to be taken and when aspects of the emerging plan will be made public for consultation and scrutiny. Not being clear about this at the outset can lead to misunderstandings later.

It also makes sense for senior leaders (administration and senior officers) to sit down at the outset of the process to discuss policy aspirations for the budget and any political ‘red lines’ that they perceive. (Having too many political ‘red lines’ should of course be avoided). At the same time officers will set out their forecasts for spending and funding and will want to identify the parameters as they see them based on their assessment of what is likely to be possible. In view of the uncertainties involved, it is important not to make any non-negotiable decisions at this stage.

It is usual to have a number of working groups and decision-making groups steering the process. The exact nature of these will depend upon a council’s normal decision-making apparatus; the budget does not sit outside these. They are likely to involve:

- The corporate management team steering the overall process.

- A cross departmental group of officers, with finance, to review proposals as they first emerge and to provide internal challenge.

- The ‘leadership team’ (senior administration councillors and senior officers) – or a sub-group of it- considering the relationships between management issues and political decisions.

Having clear lines of communication between officers and members is important, with clarity about when decisions will need to be made.

Political leadership of the process is often delegated to a portfolio holder for finance (or finance committee chair) who will undertake a lot of the detailed discussions with officers on behalf of the administration. The portfolio holder will want to ensure that member colleagues are informed and engaged as they will need to both agree to and oversee the delivery of the proposals in the budget. It is very much a local decision for political leaders at what stage they share the developing proposals with their wider group and how they achieve agreement or buy-in. Officers may be involved in briefing the wider group but should not participate in group meetings.

The budget process works best when people – both officers and members- feel comfortable with internal challenge. Formal challenge sessions (safe spaces before proposals become public) will form part of the timetable. Some councils call these ‘star chambers’ although they have nothing to do with the historic English Parliamentary court of that name which was notorious for its secrecy and arbitrary decision making!

In practice internal challenge will occur at all stages of the budget process, between officers, between officers and members and then, finally, between members as the administration seeks consensus for its emerging proposals.

In producing the timetable, it is also important to give due consideration to the final stages of the process. It is tempting to leave these details sketchy since they seem such a long way off and there is so much that might change. In practice, however, the dates for final decisions (Full Budget Council and committee meetings in the lead up) are likely already to be in the diary and there is a lot to do in these final weeks.

This may include:

- Getting approval and buy-in through the wider political party

- Consultation and stakeholder engagement

- Formal scrutiny

- Constitutional process.

Fig 3: Typical Outline Budget Timetable (Executive Model)

The committee model timetable will be very similar until close to the end. A policy committee normally takes the role of the executive and individual committees may consider their own budgets in detail in the final stages.

| May - July |

Collection of information from services on options for new spending and savings. |

| July - August | 'Rolling forward' the current budget into the next year to take account of agreed changes and inflation. |

| September |

Report produced for the executive setting out the initial budget options for the council. |

| October - November |

Review of the budget by the overview and scrutiny committee. Consulting with local businesses on the budget. |

| October - December | Listening to the views of council taxpayers. |

| December |

Analysing the grant figures provided to us by central government. Report produced for the executive taking all these factors into account. Agreeing the fees and charges set by the council. |

| January | Finalisation of budget. |

| February | Final budget proposed to council by the executive (early February). Council tax and budget setting council meeting (late February). |

Source: Test Valley District Council

Varying the Traditional Timetable

It is important to note that, just because a budget needs to be set in February or March, it is not vital or in some circumstances even advisable to wait until then to make budget decisions. Councils are increasingly finding the need to agree savings mid-year, either to contribute towards an emerging in-year deficit, to recognise that measures to reduce spending often have a long lead in period or for the very simple expedient that once a decision to make a saving has been made, it is financially beneficial to get on with it. Increasingly councils are making the burden of the last few weeks easier on themselves by making more decisions earlier.

Building a budget

The budget is a model of the council expressed as a financial plan. It needs to reflect fundamental truths about the council and the environment within which it operates. The financial failure of some authorities can be traced back to budgets that, over a number of years, did not reflect the realities the council faced.

The future is always uncertain, so budgets have to be built on assumptions and estimates. It is important to understand:

- What key assumptions have been made?

- What can change in relation to those assumptions?

- What risks are inherent in those assumptions – in general, are they optimistic or pessimistic?

Some key assumptions include:

- Economic forecasts, especially in relation to inflation and interest rates

- Expectations about pay awards

- Demographic changes, such as population growth, and how these feed through into budgets

- Changes in demand for services- related to population changes but also to other factors- for example, the demand for temporary accommodation for the homeless.

- Forecasts of the local government financial settlement (grants from government)

- Technical and political assumptions about the level of council tax.

There are a number of ways in which budgets can be constructed.

Incremental approaches to budgeting are still most common in local government and are effective for most purposes. Under this approach, budgets are constructed using the previous year’s budget as a baseline and decisions are made about ‘growth’ (increases in the budget) and ‘savings’ (reductions in spending or additional income generated). (The MTFP at Figure 2 uses this approach).

There are several strengths in this approach:

- It is possible to have some confidence in the baseline (if it is a reliable budget in the first place) because most council services do not change a lot from year to year.

- For political decision making, incremental budgeting makes for clarity about what is changing – which service budgets are increasing and which are reducing.

- If the outcome of budget setting is tight, it also allows ‘horse trading’ between various growth and savings proposals.

Incremental budgeting is thus a simple and transparent approach to budgeting which lends itself to a political environment.

The weakness of the incremental approach is that the baseline itself may never be sufficiently challenged. This is more of a weakness when budgets are tending to increase year on year, during periods when significant savings are necessary, the baseline budget will be the source of those savings and will thus be challenged more readily.

Some alternative approaches to incremental budgeting are described later in this guide.

Fig 4: Possible presentation for an incremental budget

|

£m |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline budget |

X |

|||

| Add | Growth | Demographic change |

X |

|

| Inflation/ other price changes |

X |

|||

| Local initiatives |

X |

|||

| Less | Forecast of increases in income | Government grants |

X |

|

| Retained business rates |

X |

|||

| Less | Estimated increase in council tax |

X |

||

| Budget gap/ savings target |

X |

Forecasting and Scenario Planning

The budget and the Medium Term Financial plan are both based on forecasts. Forecasting is a mixture of art and science; there are certain things we know, such as what the council’s services have cost to provide in the past, how many staff we have and how much demand for various services we currently have from the community, but various things we do not know for sure and have to estimate

A good way of getting to grips with uncertainty is to plan for various scenarios, and many councils find it useful to think about best- and worst-case scenarios, with the budget representing a ‘most likely’ scenario somewhere in the middle.

Adopting a most likely scenario, however, means that council needs to make sure it can cover off a ‘worst case’ should it arise. (See the section on resilient budgeting

Over recent years, the future seems to have become much more uncertain, and it is tempting to say that uncertainty means we cannot budget. This often manifests itself in an incomplete Medium Term Financial Plan, where forward forecasts of certain figures have been omitted because of the perceived difficulties in calculating them. (An incomplete MTFP is easy to spot because it typically shows protections for growth which flatten out over the period of the plan).

On the contrary, the whole point of budgeting is that the one thing we know for certain is that things change. Councils may need to get better at budgeting in an uncertain world, but they should not be drawn into thinking that they cannot plan.

Some forecasts carry a high level of uncertainty or even controversy, so there may be a temptation to park them for later or bury them in the detail. However, the budget process needs to consider them and understand them, including whether the assumptions that have been made are optimistic or pessimistic.

Regarding forecasts, the budget process itself is an iterative process. As the budget process proceeds over the best part of a year, more information will become available and things will change.

- Notwithstanding the fact that we know it is going to change, it is important to have a robust ‘first stab’ at a forecast which is comprehensive and where the assumptions that have been made are understood.

- At the same time, it is important not to change the figures too frequently. This is because too much change can leave everyone confused as to the size of the problem and can give an impression of chaos. The best way of managing this is to build milestones into the timetable at which the forecasts will be reviewed and targets revisited if necessary.

The Impact of Budget Monitoring on the Budget Process

The ongoing budget process will be influenced by new information emerging throughout the year, including performance against the current year’s budget in the form of budget monitoring reports. There is evidence that councils that have met with financial failure have often not learned the lessons of in-year overspends or reflected them adequately in forward budgets.

Several issues arise:

- Budget assumptions and forecasts should be reviewed to take account of new information that affects spending or income.

- If an overspend is expected, councils will take steps to contain that overspend in year, but the following year’s budget needs to reflect the risk that these measures may not be successful.

- If a budget overspend or underspend is forecast, that will affect the level of reserves the council has available for the following year.

Lessons may be learned where an overspend arises because of non-delivery of savings. Councils will need to ask themselves:

- Are the savings concerned unachievable (in which case alternative savings will be required) or merely delayed?

- What are the reasons for non-delivery of savings? For example, is this an issue with project management which can be fixed, or were the savings poorly conceived?

- What are the lessons for identification and design for future savings proposals?

The answers to these questions affect the assumptions that are made for the following year’s budget.

Budget Growth

One of the ways in which we know the budget will change is that the cost of running the council tends to increase over time. The commonest reasons for this are:

- Upward pressure on costs (inflation etc)

- Downward pressure on income

- Local initiatives.

Upward pressure on costs comes from various sources, but usually largely from inflation or similar price rises (such as pay awards or interest rate rises) or from increased demand for services.

Downward pressure on income may relate to reduced government grants but also to reduced income from rents or charges for services. The latter were a particular feature of the financial impact of COVID, people not being allowed to use leisure centres or avoiding coming into town and using car parks, for example.

Local initiatives are cost pressures over which councils should have more control. When it is affordable, councils will agree extra money for high-priority services and fund new service developments or invest in the local area. However, there is also the risk of ‘mission creep’ where extra costs derive from initiatives that have not necessarily been agreed explicitly by the council.

Although budget growth may derive from factors that are external to the council and cannot be controlled (such as economic changes) it is important to realise that the effect of these in the budget is a forecast like any other. It is therefore essential to challenge assumptions on growth.

The risk of ‘budget lag’ has been a problem for councils in the past and has even led to ‘bankruptcy’ and Section 114 reports. This phenomenon arises when a council systematically underestimates growth in its budget, so that every year there is an overspend. It can arise when councils struggle to forecast accurately but instead find themselves adjusting this year’s budget in accordance with last year’s spending figure. Thus, the budget always seems to be a year out of date.

Deliberately under-estimating growth seems like a good way of imposing budget discipline on budget managers. Managers know they are not going to have quite enough money, so they need to spend carefully and frugally. But if this is done on too large a scale, the budget parts company from the real world and becomes impossible to achieve. It is a better strategy to seek to fully identify and cost for growth so that the true size of the budget gap is visible.

Apart from the obvious financial risk of setting the ‘wrong’ budget, ‘budget lag’ has an insidious effect on the psychology of the organisation. Budget managers know that the budget they receive will be ‘the wrong budget’ and lose the motivation to stick to it. Overspends become normal and, in fact, become part of the system. It is always better to try and get growth forecasts right and not game the budget.

Savings

The difference between the baseline budget plus growth and the estimated funding available is the ‘budget gap’ or ‘savings target.’ (See Figure 2)

(The term ‘savings’ is used here to describe measures that reduce the net budget, which includes generating additional income).

The main rule with savings of course is that they must be deliverable:

- They must result in the council spending less money or generating more income than it would otherwise have done.

- There must be a practical and achievable way of getting from where we are now to this lower cost future state.

- Any costs of delivering the savings need to be funded and factored into the budget. (At the time of writing it is also allowable for certain costs of delivering savings to be met from capital receipts)

This may seem obvious, but a lot of savings proposals in public documents do not provide much information on either of these factors.

Some examples (taken from real budget reports) include:

- “Review the Communications Service”

- “Development of Leisure Services”

- “Deletion of previous year’s underspends”

- “Savings to be identified”

- “Staffing efficiencies”.

All of these might be useful things to do and may result in significant savings, but the implications are far from clear. We cannot know for sure from these examples whether members making the decision had more information available to them to allow them to make an informed judgement, but certainly members of the public, who hold the council to account, did not.

Usually, savings proposals will be put forward by officers because the managers of services have the intimate knowledge of how services work and where costs might be trimmed. Officers also have the job of delivering any savings that are agreed.

Although council reports do not necessarily need to go into full detail it is important that the organisation knows how savings will be delivered and elected members will need to have challenged savings proposals put forward by officers on this basis.

Over recent years it has become extremely common for councils not fully to achieve the savings they have set out to balance the budget. This is natural given that the financial situation has become harder, and all the ‘easier’ savings have been achieved but it introduces a huge amount of risk into a council’s financial plans. In some cases, there is evidence that savings targets had not been achieved because the full details of how cost reductions would be delivered had not been fully explored before the budget was set.

This makes it more and more important that budget planning includes appropriate challenge not just of what savings are going to be made but how they will be achieved.

Common strategies for finding savings

Usually budget managers, reporting to their service directors, will be given the first job of identifying savings from their budgets. This ‘bottom up’ approach is common and involves giving budget managers a cash limit which is less than the previous year’s budget and challenges them to identify how they would live within that cash limit.

At the same time, the corporate leadership needs to adopt a strategic, ‘top down’ approach to delivering savings by looking at the way the council does business and is organised. This can lead, for example, to council wide transformation programmes.

Both ‘bottom up’ and ‘top down’ approaches are valid and should be used but when they are used together, there needs to be an exercise, usually by the CFO, to ensure there is no double-counting of savings.

The table sets out in more detail several strategies that can be adopted to find savings, and they are not mutually exclusive. The strategy is usually proposed by officers but lead members need to be involved and agree the strategy before much work can start.

|

Top-slicing (or ‘cheese paring’) (Bottom up) |

Every service is asked to find a certain percentage of their budget. The percentage need to be set to meet the savings target in the MTFP and then some more, to provide choice. This can be a good discipline for service managers to ensure they search their budgets for efficiencies. However not all services are equally well funded or are equal priorities. This approach also delegates a lot of responsibility to service managers often leads to the suspicion that some budgets are protected like sacred cows. Finally, a cheese paring approach repeated over many years can be like a game of Jenga by which services are weakened in a haphazard way. |

|

Differential top-slicing (Bottom up) |

A variation on top slicing is to apply a prioritisation at the outset and ask for different levels of savings from different services. This can allow priority services to be protected or partially protected. However, councils need to be wary that protecting services is not the same as protecting budgets. Some services may well be able to find efficiencies while protecting essential services. |

|

Themed corporate initiatives (Top down) |

Savings strategies commonly involve a corporately led initiative around a particular theme. For example, a council may decide to reduce staffing budgets across the council by deleting all posts that have been vacant for a certain period or offer a voluntary redundancy scheme. They may decide to review the way the council manages it buildings or procures insurance. |

|

“Transformation” (Top down) |

A transformation programme looks at the whole way the council operates and delivers for the community and is often multi-faceted, involving different specialist workstreams involving staffing, buildings and technologies. Ideally a transformation programme is driven by an understanding that things could be done better and more effectively in a different way, perhaps to benefit from new technologies- but unfortunately a lot of transformation programmes are initiated by a need to find savings, so that some councils are now into their third or fourth transformation in the space of less than fifteen years. The key to a transformation programme, in terms of finding savings, is to have a robust business case that shows in some detail where savings will come from and then having a ‘benefits realisation’ approach to programme management which ensures the savings are not lost in the detail or whittled away by mission creep. |

|

Cuts (Top down or bottom up) |

Although the word is often avoided, cuts can be the natural result if sufficient efficiency savings cannot be found, or they can be a political choice. Where it is suspected that cuts will be necessary, it may be better to build them into one of the strategies above then to let them arise as a result of a failure to find efficiencies. |

As the table indicates, each of these approaches has its strengths and weaknesses and may vary depending on the overall approach to budget. Most councils will use a combination of these each year, except for transformation, which is a periodic exercise normally taking more than one annual budget cycle.

The premise behind savings needs to be challenged at every stage, not just in the scrutiny process at the end of the budget process.

Challenging yourself on savings

- Savings need to do what it says on the tin – councils should avoid balancing figures along the lines of ‘savings to be found later’ as this is an unsustainable strategy.

- Avoid euphemisms. The word ‘cuts’ is often avoided – for understandable reasons- but bland alternatives should be avoided if it is not clear to all what they mean.

- Savings need to be ‘real’ – that is they need to result in reduced spending and/or increased income relative to the baseline.

- Beware of optimism (or pessimism) bias

- Consider the risk of non-delivery

- Consider impact on outcomes – the immediate impact on services and the results they achieve in the long term. Check impact on local policies, such as responding to the climate change emergency.

- Consider the impact on resilience – what will happen if a service needs extra capacity at short notice?

- Consider impacts on individuals and groups of individuals – on residents/ users, staff, partners, others. Communication and consultation will be necessary. Check compliance with the Equalities Act.

- Consider impacts across the council – do cuts in one part of the council have an unwanted knock-on effect elsewhere? Does the cumulative effect of savings undermine the council’s operating model?

- Overshoot the savings target if possible – give choices for members, especially if the politics is difficult and last minute ‘horse trading’ can be anticipated.

As well as challenging individual savings, members also need to consider them as a package alongside other elements of the budget. Risks may aggregate, impacts on other parts of the council or on policy areas may accumulate and unforeseen consequences may ensure if this is not done. The cumulative impact on service users, as groups or individuals, needs careful consideration.

Consideration of savings also needs to take account of the timing of implementation and the costs of delivery. Large complex savings will often not deliver a full year saving in Year One and this needs to be reflected in the MTFP. The difficulty of implementing savings is a common source of optimism bias.

Funding Forecasts

The third key element of the budget is where funding is to come from. Fees and charges from services, rental income and income from investments are usually netted off the cost of delivering services. The remaining elements of funding which are normally dealt with at the bottom line involve:

- Government grants and retained business rates

- Council tax

- Use of reserves (see below).

To forecast government grants, finance staff will carefully monitor clues from government announcements and other information from government. The full Local Government Finance Settlement from central government has tended to be announced later and later each year, so it is very likely that the finance team’s forecasts will be the best information available until late in the process. This can mean that things suddenly become better or worse than expected once the Settlement announcement is made- another reason for erring on the side of caution in setting initial proposals.

In relation to council tax, the forecast needs to take on board changes in the local tax base as well as decisions by members (subject to council tax limitation) on the increase in the council tax charge. Members’ hopes and expectations on council tax ought to have been discussed at the start of the budget process – if it is decided to freeze council tax when the MTFP has assumed it will increase, that adds to the budget gap, so an early indication of intention needs to be discussed between the mayor/leader and chief finance officer.

Alternative approaches to budgeting

This guide has so far described an incremental budget approach, which is the commonest form of budgeting found in local government and has many strengths.

Two other common ways of budgeting in local government are set out below.

Zero-based budgeting

The main disadvantage of incremental budgeting, which builds on the previous year’s approved baseline, is that it takes the baseline and read and rarely challenges it.

A ‘zero based’ budgeting approach builds the budget from scratch and challenges the baseline or previous year’s budget.

It can be particularly useful if the objectives (outputs and outcomes) that an organisation is trying to achieve are constantly changing. This doesn’t apply to local government because we tend to deliver the same services from year to year, but it may be valuable in circumstances where things do change, such a change in political control.

A zero-based approach is also much more time consuming than incremental budgeting and it is less easy to see the changes in the budget that are implied – they must be spelled out explicitly.

Zero based budgeting is therefore not something that councils do every year, but it can be a useful exercise to revisit and challenge the baseline for each service every now and again, perhaps on a rolling basis or perhaps when something has changed which challenges pre-conceived ideas.

Having said that, for some individual services – notably trading services – a zero based approach is highly recommended because it ensures that both the cost base and the income target keep up with changing projections of demand.

Priority-based / Outcome-based budgeting

As it emerges from the corporate plan, the annual budget should always include consideration of outcomes and priorities. However, contact with the real world can dilute or dissipate this link.

Councils usually consider their budgets on a department by department, service by service basis, but the weakness of this approach is that many of priorities councils have and the outcomes for which they strive have a contribution from different parts of the organisation. The traditional way of breaking down the budget therefore makes it hard to match the costs (inputs) to outcomes and assess ‘true’ value for money.

Arguably incremental budgeting also tends to preserve existing ways of doing things. Focusing on outcomes potentially allows councils to think about alternative approaches to delivery.

This in turn makes it harder to direct money into priorities and to protect the outcomes that have been chosen for protection.

Priority based or outcome-based approaches to budgeting seek to overcome this by restating the budget by priority or outcome. Decision makers can then assess the value they are getting from each package of spending, and packages of extra spending or savings can be seen more clearly alongside the impact they have on outcomes or priorities.

A major advantage of these approaches is that it potentially opens conversations with partner organisation about how their budgets contribute to the same priorities and outcomes and how things might be done differently.

These approaches therefore do have benefits but there are also issues that need to be considered:

- A council adopting these approaches needs to be very specific about what outcomes it wants to achieve and its relative priorities.

- The outcomes that councils are called upon to achieve are so varied that choices between them often defy analysis.

- To reallocate costs from departments into priority or outcome packages accurately requires a lot of information on what spending achieves – for example how staff spend their time.

- A mechanism is needed for dealing with the costs of the organisation that contribute to no particular outcome or all of them, such as the chief executive’s salary or corporate support services.

- The benefits of looking at the budgets for outcomes across systems are optimised only if partner organisations agree to take part and allocate the necessary resource.

- Once budgets have been agreed based on priorities or outcomes, it is still necessary to assign budget responsibility back to budget managers, which almost invariably will mean allocation back to directorates and services.

Some councils have encountered difficulties in adopting outcome or priority-based approaches and have subsequently abandoned them. They need to be properly thought through, planned for and resourced before they are adopted.

Consideration of alternative approaches

A useful consideration in adopting alternative approaches is whether the full, textbook version of the approach is necessary to get a lot of the benefits.

For example, doing a ‘zero based budget’ exercise on each service on a rolling programme is a good way of providing challenge to the base budget within the context of an incremental system.

Similarly, conversations about priorities and outcomes can (and should) be had as part of the budget process without necessarily having to do a complicated costing exercise. Discussions about alternative way of delivering outcomes need not be confined to an outcome-based budget process.

Most councils still consider that the relative simplicity and political clarity of incremental budgeting meets their needs most of the time.

Resilient budgeting: uncertainty and risk

The budget is a model of the council’s finances and plan for the future in a complicated and dynamic environment and as such reflects a great deal of uncertainty and risk.

It is important to understand the assumptions implicit in the budget and therefore how risky the budget is. If many of the key assumptions are optimistic, then there is a greater risk of the budget not being achieved and affecting the council’s financial resilience. If assumptions are pessimistic, the council may be taking decisions that may prove unnecessary.

Scenario modelling

One way of looking at budget risk is to consider the major unknowns in terms of best case, worst case and most likely case scenarios.

The budget might then be constructed based on a most likely scenario, but with provision for the worst case, some or all of which may be available from reserves.

In all such exercises it is important to be clear about the assumptions made and to be clear that they are correctly attributed as ‘best’, ‘worst’ and ‘likeliest’. Senior managers and members will want to kick the tyres on these assumptions, thereby understanding better the risks built into their planning and the values that have been applied to the ‘best’ and ‘worst’ cases.

Each of the key variables making up the budget then needs to be modelled, taking care that the same overall assumptions are used in each case so that when they are aggregated together this creates an identifiable ‘version of the future ’, either optimistic, pessimistic or realistic. Note that the worst-case scenario is not the worst thing that can happen; it still needs to be bounded by the real world.

The budget should then probably be constructed based on the most realistic scenario, but making sure that the worst-case scenario can be funded if that is what comes to pass. Usually that will mean either including contingencies in the budget for some risks or ensuring that sufficient reserves are available for others. A contingency is an unallocated sum within the budget set aside to be allocated later. A reserve is income accumulated in a previous year which in this context has been set aside to provide for budget risk.

Scenario planning

Owing to uncertainty arising from the economic environment, and from the lack of clarity about what the government’s plans for local government funding will mean for the council, financial projections have been prepared for three different scenarios, as follows:

- Favourable

There is strong economic growth, with inflation pressures contained within the government’s long term target rate of 2 per cent. This allows the council’s external income to recover to pre-Covid levels in 2022/23 and grow strongly thereafter. New house building continues at pre-Covid levels (i.e. around 2 per cent growth per annum). Cost pressures are contained, allowing scope for budget growth.

- Neutral

Growth is slower, with external income returning to pre-Covid levels over a period of three to four years. There continues to be growth in the council tax base, but constraints in the construction sector mean there is a slow-down for the first two to three years of the planning period. The council maintains existing service levels and is able to fund inflationary increases in expenditure.

- Adverse

Government measures to stimulate the economy are constrained by the economy’s capacity to grow and the need to keep public expenditure under control. Capacity constraints and low economic growth compared with other national economies lead to prolonged inflation in excess of the government’s 2 per cent target. As a result, there is minimal growth in council external income and increased cost pressures lead to spending cuts in order to ensure that statutory services are maintained.

Details of key assumptions underlying each of these scenarios are set out below.

Source: Maidstone Borough Council

Budget contingencies

An understanding of risk is essential to good budgeting. One way of dealing with uncertainty and risk in budgets is to include contingencies. Contingencies may be set up for specific purposes or there may be a ‘general contingency’ held corporately and managed by the chief finance officer. The rationale for a general contingency is that, where it is unclear how and where additional costs may arise, it makes sense to be able to allocate funding flexibly during the year to those areas where it is needed.

Elected members should ensure they retain oversight of the budget contingency through budget monitoring reports during the year.

Inflation

A common risk that is often dealt with by contingency is inflation, especially where inflation rates are unstable. Inflation is a pernicious budgeting problem, not just because it creates rising costs which need to be funded but also because it makes it harder to apply budget discipline. If inflation rates are low budget managers can be given hard cash limited budgets within which to manage. When high rates of inflation are endemic, budget managers cannot necessarily be expected to manage the impact of these within their services, but they also provide a ready ‘excuse’ for overspends.

Councils therefore need to consider carefully how to provide for inflation in their budgets but also how the impact will be managed. A corporate approach to managing inflation and robust budget management is advisable when inflation rates are high.

Reserves

Reserves provide the ultimate funding for risk. Any overspends against the budget that cannot be managed in year will need to be met out of reserves.

There is thus a trade-off between the amount of risk that is built into the budget and the amount of risk that is provided for in reserves. Councils with high levels of available reserves can (literally) afford to take more risks, but it hard to recognise that as reserves start to fall, councils may well need to take a more robust approach to the budget process, budget management and the management of risk.

The purpose of the general reserve is to provide for non-specific risks. Earmarked reserves, where they are risk related, refer to specific risks, but not all earmarked reserves relate to risk. Reserves are covered in more detail in the ‘Must Know’ guide on local authority accounting.

The annual budget itself may contain contributions to or from reserves:

- Contributions from reserves may be a way of bridging part of the budget gap in a tough budget year or as part of the medium-term strategy, but such a budget is not sustainable if the expenditure that is funded from reserves is ongoing.

- Contributions to reserves set aside money for the future, which again might be part of a strategy, and such contributions may be the first call on the budget if reserves have fallen too low.

Where contributions from reserves have been used to balance a budget, it is necessary to reassess the adequacy of remaining reserves and it may be necessary to set aside money in the budget to replenish reserves to a resilient level. The chief finance officer has a duty to report to councils each year that the level of reserves is adequate.

Communication, consultation, and engagement

The budget is a public document and an important plan for the use of public resources. To what extent should the budget making process be public?

Communication on the budget, including formal consultation, needs to be planned for and reflected in the budget timetable. Lead officers and need to be on the same page as to what will happen when and what needs to be made public when. There should be no surprises.

The starting point for the budget process is the advice officers give about affordability. Generally speaking, this is given in public, normally in a report to the executive at the start of the process.

It is also good practice to ensure that all political parties on the council receive this message and get the opportunity to ask questions.

An important take-away from this part of the process is clarity about the size of the problem that the organisation is trying to solve. One of the reasons why it is important for the first cut of the forecast to be a thorough and complete exercise is that this figure is likely to be in the public domain.

Thereafter much of development of budget options will often be conducted in private between officers and the executive. It is likely to include the discussion of sensitive issues – such as cuts which may have an impact on service users and staff – and it is not in anyone’s interests to raise the alarm unnecessarily on proposals that may not get past the first stage. This does not preclude the need to engage with relevant partners in the development of budget options, some of which will undoubtedly be co-produced with suppliers and partners.

The administration will also have a natural desire to control the political message and it is a reasonable expectation that they should be able to present a full balanced budget proposal before they go public.

Having said that, it is considered good practice to engage with residents on the shape of the budget, perhaps as a formal consultation at this stage. The LGA’s guide to engagement is a useful resource.

There may also be a need to engage key stakeholders (including e.g. trade unions or contractors), at an early stage if they or their members are directly affected by the proposals.

Consultation

Formal consultation on the budget needs to be legally compliant, and that includes taking account of the government’s statutory guidance on best value. Section 3(2) of the Local Government Act 1999 states that councils must consult taxpayers, service users and other interested persons when deciding how to fulfil their Best Value duty. Although there is no specific requirement to consult widely on the budget, (the council must consult with non-domestic rates payers on its plans for expenditure under Section 65 of the Local Government Finance Act 1992), it is an important element of achieving best value and many councils take the opportunity of setting the budget to meet their statutory best value responsibility.

There is also a common law expectation and, in the case of some services, there are legislative requirements to consult those affected on proposals and these may apply to individual proposals within the budget, such as proposed savings.

Councils should of course provide an opportunity to comment to all relevant stakeholders, including partner organisations, where they have not already been involved in co-production of proposals.

Councils must also ensure that they comply with legislation, good practice and local agreements to consult staff and trade unions. Councils need to take local legal advice on how these principles including consultation legislation and guidance applies to their budget process.

The Local Government Finance Settlement

One of the frustrations of the annual budget process is that central government leaves it late to notify councils of their funding settlement for the year in question. While concerted work on the budget is likely to have been going on since the late Spring and Summer, a draft financial settlement is not normally published for consultation until the week or two before Christmas. The final settlement is announced in late January or February but is not usually very different from the draft.

In recent years there have been an improvement in the form of an earlier policy statement which seeks to set out the parameters for the settlement, including such things as the council tax limitation rules. This has been helpful to councils.

Experienced and well-networked finance officers will be able to forecast a settlement within realistic parameters based on the previous year’s settlement, overall government spending plans and other announcements and signals from government. However, it is not at all unusual and in fact normal for councils to have to adjust their budget plans in the light of the settlement.

Agreeing the Budget

The process for final agreement of the budget needs to be part of planning from the outset, and it can be either relatively simple (for example where there is a clear council majority, strong leadership) or difficult (for example where there is a minority administration, and the opposition might therefore be able to vote the budget down).

The council’s constitution will contain ‘Budget and Policy Framework Procedure Rules’ or similar which will set out the formal stages that need to be taken. The monitoring officer’s (or head of legal’s) advice should be taken on the interpretation of the constitution, what is allowed and what isn’t.

In addition, the statutory officers (chief executive officer, MO and CFO) will often set ground rules, covering such matters as briefing opposition groups and submission and consideration of budget amendments. This can be helpful in ensuring that everyone is on the same page and that it is not necessary to constantly refer to the constitution document itself throughout the process.

It is important that the budget proposals are compliant with the council’s Equalities Act duty to address discrimination and promote equality. Budget proposals need to be subject to Equalities Impact Assessments (EqIA) to assessing the effects or impacts of a council policy or function on removing barriers to equality.

Failure to comply with common law principles around decision making and statutory requirements may lead to the council’s decisions being overturned in judicial review.

Writing the report

Formal approval of the budget revolves around a formal set of papers that make their way (depending on the governance model adopted) from cabinet/executive or policy committee to scrutiny or service committees and thence to full council.

A lot of information needs to be put into the public domain at this stage and into the hands of full council and it is worth spending some effort ensuring that attention is drawn to the key issues.

A ‘three levels of reporting’ approach might be usefully adopted:

- A summary document setting out the key decisions to be made and the main salient points in relation to each one.

- A narrative section that goes into further detail

- Appendices which set out the technicalities, and aspects of the background that has previously been reported.

Good practice suggests that the report should:

- Give consistent messages

- Be non-repetitious

- Use tables and charts as well as narrative

- Avoid technical jargon where possible

- Explain technical jargon where necessary.

Scrutiny

Good practice says that scrutiny committee(s) ought to be involved throughout the budget process. Otherwise, scrutiny is in the position of having to absorb and comment on a lot of material in a short space of time.

The Financial scrutiny practice guide is a resource available on the Centre for Governance and Scrutiny (CfGS) website.

The guidance suggests that there are four roles for scrutiny in setting the budget:

- Reviewing how resources are allocated

- Reviewing the integration between finance and service planning

- Testing out and making explicit whether the council is directing its resources effectively

- Providing, in a public forum, challenge to the executive’s management of the public finances, and a different perspective.

This remit makes budget scrutiny a year-round exercise. Although this might not always be welcome to the executive, it is believed this approach leads not just to better scrutiny, but to better understanding by scrutiny members of the challenges faced by the council and hence by the executive.

The formal stages of scrutiny of the annual budget take place at the end of the process in accordance with the Budget & Policy Framework Procedure Rules as set out in the council’s constitution. Scrutiny committees will consider the budget proposals put forward by the executive and often will comment back to cabinet/executive before the budget is submitted to full council.

As CfGS points out, this is very likely to be too late for scrutiny to influence the process on constructive grounds. By this stage, any opposition to the budget is likely to be rooted firmly in politics. However, it is suggested that scrutiny can still play a role by:

- Summarising its involvement in the budget development process so far – the opportunities that councillors have had to exert some influence, and the results of that process.

- Highlighting areas that remain contentious, and where scrutiny has made recommendations and suggestions that have not been taken up.

- Highlighting and discussing the impact of elements of the budget on local people.

Opposition amendments

Subject to the realities of local politics and the arrangements set out in the constitution, opposition groups on the council have a justifiable expectation to challenge the budget politically and to put amendments to the budget to be considered as motions by full council.

Such amendments need to be given full officer attention, reflecting the fact that officers are there to support the council as a whole, not just the administration.

The following matters need to be considered:

- A budget amendment needs to deliver a sustainable and resilient budget on the same terms as that put forward by the executive. Thence any proposals for additional spending, for example, need to be matched by savings and any use of reserves (for example) needs to be cognisant of the same officer advice given to the executive.

- Opposition amendments need to receive the advice of officers as to such matters as their impact, deliverability and legality on the same basis as the proposals of the executive.

- Thus, opposition members and parties need to be encouraged to discuss their proposals with officers as early as possible, with appropriate cover for confidentiality.

- For proposals that have a significant impact, there will not necessarily have been time for consultation, so budget amendments may need to reflect suitable caveats and contingencies allowing for this.

To ensure that there is no misunderstanding on these points, it is a useful practice for the chief executive, chief finance officer and monitoring officer to give guidance on amendments to opposition parties well before the full council meeting. This guidance should be in writing. This provides an opportunity to provide assurances on confidentiality and equal treatment between parties and to offer officer advice in helping to shape amendments.

The worst case scenario is for amendments to be tabled at the latest possible time under the constitution, which may lead to amendments having to be disallowed or officers’ advice given at the meeting is not welcome to the opposition.

The Chief Finance Officer’s Section 25 report

As part of the final annual budget decision, the CFO has the statutory responsibility to make a report on the robustness of the budget process and the adequacy of financial reserves. There is limited guidance on what this involves and CFOs take different approaches to this requirement. Since the CFO will undoubtedly have been involved in the budget process and will have been responsible for advice given to members on the level of reserves, this should be a reiteration of advice already given to members, but it serves the purpose of assuring elected members and the public that the decisions about to be taken are robust.

The messages put across in the Section 25 report or statement should clearly be consistent with advice given to members throughout the budget process, and any advice the CFO has a result of their report should not come as a surprise.

The external auditor will also comment on these matters as part of their annual commentary on value for money, although usually only retrospectively.

Section 114

This guide is not intended to provide advice on the application of Section 114 of the Local Government Act 1988), but it is important to note that the CFO is also under a duty to report to the council, and advise the external auditor, if it appears to them that...

“the expenditure of the authority incurred (including expenditure it proposes to incur) in a financial year is likely to exceed the resources (including sums borrowed) available to it to meet that expenditure.”

It goes without saying that the period leading up to a decision on the budget is a time when it might become clear to the CFO that this requirement has been triggered. A Section 114 alerts the government to an issue and, to date, has always resulted in some form of government intervention.

Statutory Calculation and Statutory Date

In formal terms, the full council determines the level of council tax and the statutory calculation that is made, and which council approves, is written on the basis that council tax is the balancing figure after the council has calculated its expenditure and factored in its other income. From a political and practical standpoint of course, this is not what happens. Councils will often start with a view about the level of council tax they want to set and in practice, the level of savings required is the balancing figure. This is especially the case while council tax increases are subject to government limitation.

Statute requires the council to have considered and approved its budget before 11 March for a budget year starting on 1 April. The council therefore cannot refuse to set a budget. In practice there are unlikely to be any legal consequences for missing this date, but in practical terms the council needs to have approved its council tax in time to allow statutory billing information to be notified to taxpayers so that tax collection can begin, and any delay may mean a loss to the council.

Delivery

A key criterion for a robust budget that will ensure financial sustainability and resilience is that it should be deliverable in practice.

Guidance on the delivery and monitoring of budget plans is not within the scope of this ‘Must Know’ guide.

Self-evidently, the budget that is agreed by full council must be capable of being delivered both in terms of its individual proposals and in its entirety, on the basis of sustainability and resilience.

It is a bad idea to leave matters undecided in order to get through budget setting, but it is common for councils to set budgets that are less than robustly deliverable:

- Savings still to be found.

- Savings propositions undeveloped or vague in their meaning (e.g. ‘transformation of services’)

- Reserves used on the basis that they will be replenished at some uncertain future date.

The proximity of the agreement of the budget to the start of the financial year to which it relates means that inevitably planning for delivery will need to have started much earlier. This includes, for example, setting up of major projects and programmes to deliver savings.

Alternatively, the budget may have provided for only a part-year effect of any savings agreed to allow for preparatory work to take place after the budget is set.

The extent to which either of these strategies will be used will be based on a judgement by officers about how likely it is that various proposals will be approved; hence how much preparatory work can be anticipated and the risk that pre-work may be wasted.

Key lessons

The successful agreement of a robust and deliverable budget depends on a lot of factors coming together but the following appear to us to be particularly important:

- Understanding

Councils need to know what they want the budget to deliver, and they need to understand their local area and the context that they face. They particularly need to understand where forecasts and estimates included within the budget are risky and how those risks are to be managed. - Organisation