Executive summary

The Chancellor is conducting the 2020 Comprehensive Spending Review (CSR) in unprecedented conditions. As a nation, we are dealing with the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on people, the economy and public finances. This is alongside the transitional period, following the UK’s exit from the European Union, coming to an end on 31 December.

As we start to look forward, the CSR is a once in a generation opportunity to shape the direction of this country for years to come. We need a collective effort to rebuild our economy, get people back to work, level up the inequalities some face and create new hope in our communities. Responding to the significant economic challenges ahead requires renewed joint endeavour between local and national government as equal partners.

No other body understands local areas better than councils. The highly-valued services we deliver – including public health, adult social care, children’s services, homelessness support, provision for the vulnerable and those in financial hardship – have been absolutely crucial to the initial COVID-19 response by protecting lives and livelihoods. Councils are ambitious for our communities now and into the future, and always stand ready with local solutions to the national challenges we face.

The effective delivery of this next phase will depend on all agencies working in partnership at the local level, and councils are best placed to convene this work. Different areas of the country will require a unique and coordinated response in the coming months and years. Local leaders stand ready to bring government departments and agencies together to deliver locally determined and accountable outcomes. This will allow us to address the biggest public service challenges that have held our nation back for so long, such as social care, health and skills and employment. Our paper, Re-thinking Local, set out our vision for this new approach to devolution.

Bringing power and resources closer to people is the key to delivering better outcomes for communities, tackling deep set inequalities and building inclusive growth across the country. Councillors and their councils have the democratic mandate, expertise and local insights to change our communities for the better. People both rely on, and are reassured by, their local leaders. The Local Government Association’s (LGA) recent polling shows that 73 per cent of residents trust their local council to make decisions about how services are provided in their local area. With the right powers, sustainable funding, and enhanced flexibilities local government can build on the positives we have achieved in the past few months and ensure our communities prosper for the future.

One only needs to look at how councils responded to COVID-19 in an unprecedented manner, even with pressures growing on increasingly fragile services that supported the most vulnerable, such as children’s services, adult social care, and homelessness support.

Despite these unresolved issues, at a time of national crisis, councils put their local leadership role first. They moved at pace, used innovative approaches and worked flexibly to set up completely new services to support the most vulnerable, reshaped and redesigned services such as waste collection to keep them going virtually unaffected, and were central to the economic support provided to residents and businesses. Central Government and local communities trusted them, and they delivered. Throughout, councils learnt from and supported each other through sector-led improvement.

However, as things stand, many councils are in a precarious financial position. After a decade of reductions in funding and rising demand – from which we seemed to be beginning to emerge –councils, along with the rest of the nation, have faced the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on their citizens, staff, services and budgets. Estimates by the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) suggest that another £2 billion might be needed this year to meet all the pressures and non-tax income losses that councils have experienced and will experience as a result of COVID-19, but that this could rise to £3.1 billion depending on whether councils’ assumptions about the end of the pandemic are correct. Further funding to cover local tax losses, as well as one-off costs that will be incurred to help local areas recover from the impact of the pandemic, will be required as well.

But we also need to look beyond 2020/21 to the next few years. Councils will continue to face demand pressures on their day-to-day services, some pre-existing, others made more significant by the lasting impact of COVID-19 – all against weaker prospects for income, such as local taxation, fees and charges.

As part of its recent analysis commissioned by the LGA, the IFS estimated that councils face cost pressures of nearly £9 billion by 2023/24 in comparison to the 2019/20 starting point. When considering other pressures set out in its report, such as the fragility of the adult social care provider market and the impact of a future revaluation of pension funds, this could lead to a funding gap of £5.3 billion by 2023/24 even if council tax increases by 2 per cent each year and grants increase in line with inflation.

The IFS is also clear that we are still in a period of great uncertainty, with no allowance made for longer-lasting service demand impacts of COVID-19 to councils. The IFS’s upper estimates of all the pressures outlined above as well as challenges of recovering self-raised income suggest that the funding gap could end up being as high as £9.8 billion by 2023/24.

In addition to putting current services on a sustainable footing, councils need the resources to rebuild and recover on issues such as early intervention, public health, concessionary transport and others. Our submission sets out these further pressures on core funding in more detail.

It is clear that the starting point for a new approach to public services, a joint endeavour with national government, in every part of the country needs to be a re-think of public finances with a multi-year financial settlement which provides local government with certainty over their medium term finances, sufficiency of resources to tackle day-to-day pressures and the lasting impact of COVID-19 on income and costs, and that recognises the benefits of investment directed by those closest to the opportunities for shared prosperity.

To achieve this, the Spending Review will need to move away from the traditional drivers of departmental spending towards a degree of fiscal decentralisation in line with some of the world’s most productive economies. The economic challenges our communities are facing require a bold response – place-based budgets which are in tune with the needs of the local economy. We need to re-think how we fund public services, not try to fit new and bold ideas into old frameworks.

This submission, separated into five distinct chapters, sets out how local government can act as the driver to achieve shared priorities between central and local government. Together, we can strengthen the UK’s economic recovery, level up economic opportunity, tackle social and health inequalities, improve outcomes in public services, achieve net zero carbon emissions and improve the value for money of public spending.

- Overall council funding makes the case for sustainable core funding for local government and enabling councils to bring together budgets of public services across a place to eliminate duplication of effort and drive savings to the public purse. Key proposals in the chapter include:

- A multi-year ‘core’ local government funding settlement which provides sufficient certainty and resources to help councils recover from the impact of COVID-19. Taking the pressures estimated by the IFS together, councils face an estimated a funding gap of £5.3 billion by 2023/24 which could grow to as high as £9.8 billion due to the uncertainty resulting from the continued impact of COVID-19. This gap is already after taking annual 2 per cent council tax increases and inflation-linked growth in grants.

- Our four-point plan to allow councils to deliver further public spending efficiencies by joining up local services in a place and eliminating the fragmentation of funding;

- Our proposals to reform and improve local taxation, as well as using the business rates review as an opportunity to discuss how council funding can be further diversified through other forms of taxation.

- Care and health inequalities builds the argument that services for children and adults, combined with a reinvigorated local public health offer, provide the opportunities to tackle health inequalities, manage the on-going impact of COVID-19 and ensure older and disabled people can access the care and support they need. Getting the support right for those who need it most is essential to minimise the costs of poor health, extreme inequalities and poor outcomes later on. Key proposals in the chapter include:

- Our reiterated commitment to work with the Government to deliver a reformed system for funding adult social care and the principles for the delivery of care and support that should underpin the new funding framework;

- Opportunities to improve the life chances of children and young people by ensuring access to high quality services and support including children’s social care, education and youth services;

- An ambitious four-sided strategy for unleashing investment and improvement in public health services, through the recovery of the public health grant, a Prevention Transformation Fund, place-based council leadership and incentivising behaviours.

- Environment and climate change deals with one of the most important issues facing the world today, highlighting the vital role councils play in tackling it. Key proposals in the chapter include:

- A call for crucial investment to allow councils to help Government achieve its aim for the UK to become a net zero carbon economy in 30 years’ time;

- Measures needed to make sure that the ambitious waste and recycling reforms are introduced in a financially sustainable fashion; and

- Ways to improve our ability to adapt to, and manage, the impacts of climate change, including flooding.

- Economy and ‘levelling up’ focusses on the role councils can play in the economic recovery from COVID-19 and the subsequent recession, in particular through greater devolution and powers to steer resources to local economic priorities. Key proposals include:

- A revamped framework for providing councils with capital infrastructure funding, to match the direction set out in the National Infrastructure Assessment;

- An innovative, devolved approach to make sure that local residents have the right skills to match work opportunities of the future; and

- Tackling economic issues affecting the most vulnerable residents, such as homelessness and the welfare safety net.

- Finally, Great places to live showcases the role councils play in building thriving local areas which can boost the sense of community, connection and pride in a place, which can yield further positive economic benefits. Key proposals include:

- Measures designed to improve the public realm, for example through thriving parks and green spaces,

- Funding, powers and flexibilities to help councils deliver housing that is both affordable and sufficient in numbers; and

- Making sure our communities are safe and well looked-after and can rely on essential regulatory, community safety and emergency services, such as fire and rescue.

Combined together, they present a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to re-think public spending in a way that is fit for the future, flexible to allow the delivery of local priorities, and empowers councils to deliver on the ambition for our communities that central and local government share.

Overall council funding

A strong and certain financial foundation

1.1 Councils are ambitious for our communities now and into the future, and always stand ready to offer local solutions to the national challenges we face. This includes continuing to deliver for our communities during these unprecedented times, while also boosting local efforts to revive and rebuild the economy. However, they require the right powers, sustainable funding and enhanced financial flexibilities to do so.

1.2 The COVID-19 pandemic is already having a profound impact on the economy. There has been an increase of over two million in Universal Credit claimants, which has also translated into higher demands on council tax support. Meanwhile, the Job Retention Scheme is supporting six million jobs on the basis of the latest data, many of which are likely to be supported until the end of October, at which point the scheme is expected to end.

1.3 The economic impact is having a big effect on public finances – both for the Exchequer through national taxation and local government through local tax income, fees and charges.

1.4 The best possible efforts of councils to spark local recovery will not bear fruit without sufficient funding and a sustainable local government finance system to underpin them all. Councils need confidence in the financial system to be able to act, and this is particularly important if councils are expected to be innovative and invest in local solutions.

1.5 Best value for the use of public resources can only be achieved if councils are able to plan and are placed on a sustainable long-term financial footing.

1.6 Prior to the pandemic, councils had already dealt with a £15 billion reduction to core government funding between 2010 and 2020. While a significant part of this challenge has been met through efficiencies and transforming services, councils still had to ration services such as cultural services, economic development, libraries and others to ensure they could continue to protect vulnerable children, for example.

1.7 In addition, councils were facing a funding gap of £6.5 billion by 2024/25, even under assumptions of sustained council tax increases of 2 per cent each year, fees and charges rising and continuing business rates growth.

1.8 Now, councils are also dealing with the sharp end of the immediate financial impact caused by the extra costs, loss of income and cash flow pressures arising from COVID-19. Savings plans and transformation efforts have been put on hold, further exacerbating this unprecedented impact.

1.9 Work by the IFS has indicated that at least £2 billion is still needed to meet the full financial impact of the pandemic in 2020/21 – with the potential for this to grow to as much as £3.1 billion, before even considering the impact of lost local taxes on 2021/22 and beyond.

1.10 There is still significant uncertainty about future pressures related to the pandemic. For example, at the time of writing COVID-19 caseloads are rising, local lockdowns are expanding and the Government is announcing new national initiatives, such as COVID-19 marshals.

1.11 Therefore it is vital that the Government provides a cast-iron guarantee that the financial challenge facing councils as a result of COVID-19 will be met in full – where needed on an on-going basis and not time-limited – before further recovery measures are even considered, as otherwise they will be built on a barely existing foundation. This includes full compensation for lost income and local tax losses. The latter are covered later in this chapter.

Building a strong financial foundation

1.12 To deal with the impact of the pandemic, councils had to reconfigure their services delivery quickly. A large number of temporary services and structures have been introduced, such as:

- Support hubs, especially with respect to shielding the vulnerable

- Local resilience fora

- Measures for businesses as well as residents struggling to pay council tax

- Other specific local services.

1.13 Other pre-existing services have either seen an increase in the cost base that will be very difficult (and not necessarily desirable) to drive down, or are expected to see a ‘bounce-back’ once the pandemic is over. For example:

- Councils have rightly provided adult social care providers with support to help meet additional COVID-19 costs. However, even when the pandemic is over, care providers will be struggling – they already were before COVID-19 – and anecdotal concerns suggest that increased care home vacancies will mean some providers will struggle to stay sustainable on the current income rates. All this implies that councils will find it very difficult not to make the ‘temporary’ cost uplifts permanent and might need to go further to sustain a functioning market.

- Homelessness support will be expected to operate at the increased intense level. The drive to get 90 per cent of homeless people into accommodation has been a big success but it comes at a large cost and the pressure will be on to keep homeless people supported in accommodation once COVID-19 passes.

- There is anecdotal evidence that demand for children’s social care has reduced during the pandemic. This means that, regretfully, a spike of pent-up demand for support to vulnerable children is likely in the ‘new normal’, especially with the evidence that domestic violence is sadly on the rise.

1.14 All of these issues are covered in greater detail in other chapters of our submission.

1.15 Commissioned by the LGA, the IFS has independently reviewed the future funding outlook for councils prior to the Spending Review, including ‘business as usual’ pressures, cost impacts of the pandemic that might be permanent and the potential long-term impact of the economic changes on local income, such as local taxes, sales, fees and charges.

1.16 As part of its analysis, the IFS estimates that councils face cost pressures of nearly £9 billion by 2023/24 in comparison to the 2019/20 starting point.

1.17 When considering these cost pressures and other ‘business as usual’ pressures set out in their report, such as the fragility of the adult social care provider market and the impact of a future revaluation of pension funds, this could lead to a funding gap of £5.3 billion by 2023/24, even if council tax increases by 2 per cent each year and grants increase in line with inflation.

1.18 The IFS is also clear that we are still in a period of great uncertainty, with no allowance made for longer-lasting cost impacts of COVID-19 to councils. The IFS’s upper estimates of all the pressures outlined above as well as challenges of recovering self-raised income suggest that the funding gap could end up being as high as £9.8 billion by 2023/24.

1.19 The funding gap set out in the table below is calculated on the basis of maintaining the current service levels and quality and only accounts for ‘business as usual’ cost pressures.

1.20 We believe that there are a number of other risks to councils’ financial stability which need to be addressed through additional funding. This includes pre-existing financial shortfalls in concessionary fares funding, persistent overspends in children’s social care and homelessness budgets and future new burdens which can be quantified at this time.

1.21 However, councils are ambitious beyond just managing the current challenging state of local finances and services. A number of quantifiable pressures and issues that need to be solved to improve outcomes for local citizens are outlined throughout our submission. They would also have to be funded through additional core funding. This includes, but is not limited to, reinstating early intervention grant, reforming adult social care pay and others. They are listed in the table below and are collectively worth nearly £3 billion on top of the funding gap above.

1.22 To deliver on the Government’s priorities and ambitions, councils have to build on a stable foundation. Across the submission, we are calling on the Government to provide an additional £10.1 billion in core funding by 2023/24, made up by the £5.3 billion funding gap to sustain 2019/20 service levels (already assuming annual inflationary increases to grants and 2 per cent annual council tax increases), £1.9 billion to deal with other quantifiable pressures to stabilise the sector and £2.9 billion of other core funding requirements to help councils improve their core service offer. These figures are broken down in the table below.

1.23 This is in addition to our proposals where specific revenue and capital funding would be required, such as public health funding. They are covered throughout the submission.

Table 1.1. Core funding requirement for councils: breakdown

|

Element |

Paragraph of submission |

Value, £m (2023/24 in comparison to 2019/20, nominal terms) |

|

IFS - central additional ‘business as usual’ cost pressures estimate |

|

8,698 |

|

IFS – central adult social care provider market pressure estimate |

|

1,690 |

|

IFS – central estimate of potential additional costs due to 2023 pension revaluation |

|

678 |

|

IFS – income growth estimates (includes 2% annual increases in council tax and increases in grants in line with CPI inflation) |

|

(5,805) |

|

Funding gap to retain 2019/20 service levels (in addition to inflation increases to core grant and 2 per cent council tax increases) |

|

5,261 |

|

Other underlying pressures and quantifiable new burdens that require appropriate funding |

|

|

|

Pre-existing persistent children’s social care overspend (2018/19 overspend, uprated for demand and inflation using IFS assumptions) |

|

1,013 |

|

Pre-existing persistent homelessness overspend (2018/19 overspend, uprated for demand and inflation using IFS assumptions) |

|

160 |

|

Meeting the shortfall in concessionary fares funding |

4.104 |

700 |

|

Building Safety Bill new burdens |

5.81 |

22 |

|

Mental Health Act – new burdens |

2.170 – 2.172 |

10 |

|

Total other underlying pressures and quantifiable new burdens |

|

1,905 |

|

Other quantifiable core funding requirements to help councils improve and recover services: |

|

|

|

Reinstating early intervention funding to 2010/11 levels |

2.60 – 2.63 |

1,700 |

|

Reforming adult social care pay to match NHS |

2.34 – 2.35 |

1,000 |

|

Restoring the Social Fund to 2013/14 funding levels |

4.72 |

176 |

|

Local digital infrastructure champions |

4.51 |

30 |

|

Total quantifiable core funding requirements to help councils improve and recover services |

|

2,906 |

1.24 While the list above is extensive, it is important to note that there are also pressures and new burdens identified throughout this submission, the funding of which falls on core council resources and are more difficult to quantify at this time. They are also listed in the table below together with references to specific parts of this submission. These pressures and burdens need to be assessed, funded and kept under review.

| Element | Paragraph of submission |

|---|---|

|

Other unquantified pressures which require a boost to core council funding covered by this submission: |

|

|

Adult social care sleep-in shifts: payment of full NLW pending Supreme Court case |

2.37 – 2.39 |

|

Revenue cost of supported housing |

2.40 – 2.42 |

|

Child protection pressures |

2.64 – 2.67 |

|

Revenue cost of new children’s homes |

2.68 – 2.71 |

|

Boosting mental health services |

2.157 – 2.167 |

|

Revenue cost of low carbon initiatives |

3.16 – 3.18 |

|

Revenue costs of climate adaptation measures |

3.33 – 3.40 |

|

Delivery of local clean air plans |

3.46 – 3.48 |

|

Expansion and maintenance of trees and woodlands |

3.54 – 3.57 |

|

Boosting capacity of trading standards, environmental health and other regulatory and protective functions |

5.23 – 5.30 |

|

Other unquantified new burdens: |

|

|

Liberty protection safeguards |

2.171 |

|

Autism Strategy |

2.43 – 2.51 |

|

Armed Forces Covenant |

2.175 – 2.178 |

|

Environment Bill |

3.10; 3.51 – 3.53 |

|

Planning White Paper |

5.21 |

|

Domestic Abuse Bill |

5.64 – 5.65 |

|

New Protect Duty |

5.76 |

|

New burdens resulting from final EU Exit arrangements |

N/A |

Planning certainty

1.25 With a Spending Review taking place in October at the earliest, councils will have gone through three years of quick-fire, short-term budget setting exercises since 2018. In addition, the 2021/22 financial year was meant to see the culmination of the Fair Funding Review, the move to 75 per cent business rates retention and the business rates revaluation all being implemented from next April. All of these have now been postponed – the revaluation will be introduced from 2023 and the other reforms have no specific time frame.

1.26 Without even considering the impact of the pandemic, such a lack of financial planning information does not allow councils to make meaningful and sustainable decisions. For example, councils might make service cuts which would otherwise not be necessary if they had better information. The risks connected to the long-term impact of COVID-19 on local income make this even more challenging.

1.27 A three-year Spending Review presents an opportunity to draw a line under short-term budgeting and to allow councils to set reliable medium-term financial strategies. To do so, the Government should commit to a three-year local government finance settlement to follow the Comprehensive Spending Review. This should encompass general grant funding, specific grants such as the public health grant and council tax flexibilities.

1.28 The impact of the pandemic has not changed the reality that the way general government grants are distributed between councils remains complex, opaque and out of date. It is not possible to succinctly explain why the funding allocations for different councils are what they are. However, it is also clear that any review of distribution arrangements puts a multi-year local government finance settlement at risk, with an impact on certainty. We are calling on the Government to resume the Fair Funding Review, but with a guarantee that the transitional mechanisms will not only ensure that no councils experience a loss of income but should also protect councils from reductions from the path laid out by a three-year settlement, so that they can plan with confidence. The same provision should apply to any business rates reset.

1.29 Councils had to revisit and revise many of their services to react to the impact of the pandemic and it is yet to be seen how permanent some of those shifts are. This means that, when the Fair Funding Review is relaunched, the Government needs to review progress made to date to ensure that it is still fit for purpose, or flexible enough to deal with any such shifts in council service models. One example could be the council tax adjustment (especially the council tax support and collection rate elements).

1.30 Councils’ confidence in business rates as a reliable income source with a future has reduced. The taxbase is currently eroded and council income is propped up by section 31 grants which would fall away at the next reset. In fact, if COVID-19 reliefs become permanent, business rates retention shares would have to go up significantly just to keep the same level of income with local government, without any roll-in of grants.

1.31 While a call for evidence has been launched, the Government’s fundamental business rates review is in its infancy. The next revaluation of business rates will also be highly controversial regardless of when it happens, which will add to the angst surrounding the tax. To aid certainty, the LGA is calling on the Government to not go ahead with 75 per cent local retention of business rates and only revisit this, if appropriate, after the business rates review concludes.

Efficiency

1.32 It is important to recognise that one of the goals of the 2020 Comprehensive Spending Review is to set a new path towards sustainability of public finances after the impact of COVID-19. This requires looking at how the public sector spends money, and on what priorities.

1.33 Councils have delivered more than their fair share of the burden of putting public finances on a more sustainable footing over the past decade. Our analysis shows that around £15 billion of core central government funding has been taken out of councils’ budgets between 2010 and 2020, a drop approaching 60 per cent in real terms.

1.34 Recent research has brought together evidence of the wider financial and economic impact of council spending. This shows that despite funding reductions, council services and activities have delivered significant financial benefits for other public service providers: reducing the demand for some services and providing more cost-effective alternatives to others.

1.35 Local government stands ready to help Government with the task ahead. However, a task of this magnitude, following the experience of the previous decade, needs a completely different approach which unlocks the capabilities of local government to deliver savings across the public sector, instead of looking at local government budgets as just another budget line.

1.36 The traditional means of delivering efficiencies within local government have been exhausted. LGA work undertaken prior to the pandemic showed that the vast majority of remaining variation in spending between councils on older people’s adult social care and children’s services – the two biggest service areas – was explained by factors outside the control of councils (78 per cent and 71 per cent respectively).

1.37 The need to focus all efforts on tackling the impact of COVID-19 locally has also meant that many savings and transformation programmes aimed at delivering savings this year have had to be postponed or cancelled. The data from the July round of the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (MHCLG) financial information survey suggests this could be worth around £600 million.

1.38 Therefore, instead of looking inward and risking financial sustainability, councils are ready to help Government deliver further significant efficiencies to the public purse through the following four-point plan:

- A renewed focus on prevention, backed by Government investment. A sure-fire way to address existing and future demand for services such as social care, homelessness support and community safety is to invest in lower cost approaches which help strengthen people, communities and local infrastructure. However, with council budgets stretched, a challenge of this scale needs to be kickstarted with Government investment. Our submission provides a rich set of such investment opportunities.

- Reducing the fragmentation of government funding. Research commissioned for the LGA found that in 2017/18, nearly 250 different grants were provided to local government. Half of these grants were worth £10 million or less nationally. At the same time, these grants are highly specific – 82 per cent of the grants are intended for a specific service area. Around a third of the grants are awarded on a competitive basis and often the small amount of grants means that more is spent by councils on preparing bids than is received back. All of these factors mean that if fragmentation and ringfencing of grants is reduced, the system of local government funding can provide much better value for the same amount of funding.

- Bringing budgets together in a place. The approach to tackling fragmented funding can go much further, by looking beyond just local government funding. We need to allocate money to places and not departmental silos. A shared financial and governance framework will mean that services can better align with local priorities and local duplication of efforts can be eliminated. This Comprehensive Spending Review should place emphasis on communities and place by introducing multi-department place-based budgets, explicitly built around the needs of diverse local communities using equality impact assessments.

- Supporting councils to make local self-financed investments to help delivery of transformation of services with associated savings or generated income. This includes improvements to the general capital funding and borrowing framework and improving the consideration of local impacts of investment through the Green Book. This is covered in more detail later in this chapter.

Workforce and capacity

Recruitment and capacity

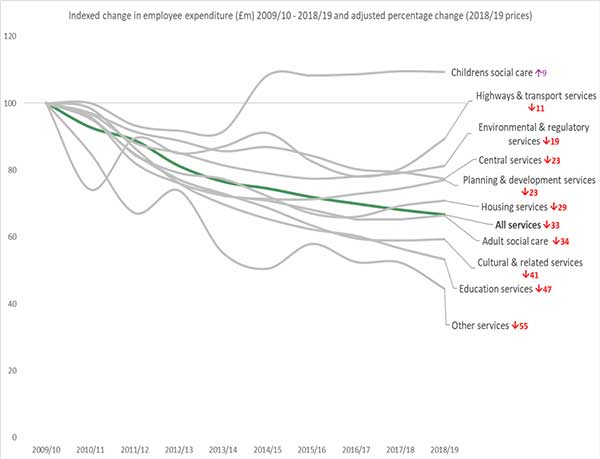

1.39 There have been reductions in most sections of the local government workforce in recent years which has resulted in potential resilience and capacity concerns in light of the foreseeable and unforeseeable demands of events such as COVID-19, EU Transition and the fragility of the social care sector. Reductions in expenditure as shown in the chart below are reflected in reductions in employment. Some of the change reflects the academisation of schools and outsourcing.

1.40 According to the ONS quarterly public service employment survey, in the broadest terms, between Q1 2010 and Q2 2020 the headcount of local government staff fell by around 40 per cent, from 2.1 million to 1.2 million with the full-time equivalent totals for the same periods falling from 1,466,000 to 920,600. This is only in part explained by academisation as the headcount for full time teachers in state-maintained schools in England in 2018/19 was relatively unchanged from 2010/11.

1.41 The only area where staffing has clearly grown over the period is in children’s and family social care where staff levels were 24,890 for the year ending September 2013 increasing to 32,917 by September 2019 (in context, the number of looked after children increased by around 25 per cent in the 10 years to 2019).

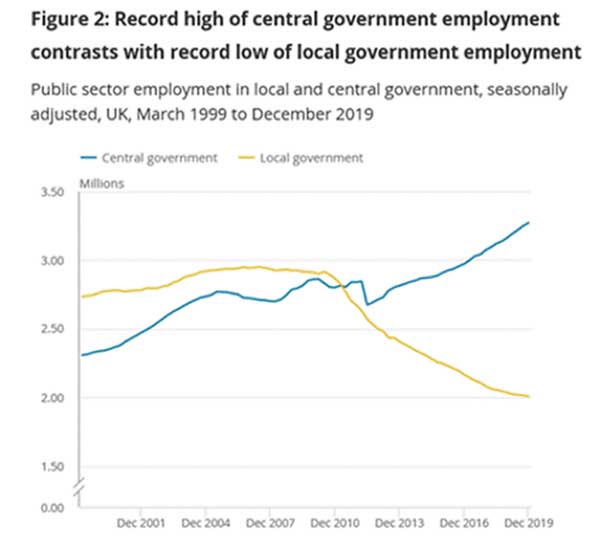

1.42 This contrasts with growth in other public service employment, especially recently, as shown in the next chart.

Chart 1.2. changes in employment, central and local government

1.43 A useful independent analysis of the effects of these reductions on services can be found in a 2018 study by the Institute for Local Government. The study shows for example that 80 per cent of respondent councils had made redundancies as a direct result of austerity and that 90 per cent had reduced services. The survey also examines some of the routes councils adopted to change services. All respondents have redesigned services and the vast majority have used technological solutions.

1.44 However, the limits of innovative change have now been reached in many cases and the experience of the pandemic shows that investment is now needed in both the short and long term to ensure local authorities have the right skills and experience in place to meet these demands effectively. The challenge is threefold:

- in some areas, such as environmental health and social work, there is a shortage of qualified, suitably experienced individuals in these professions;

- in other areas such as building control and engineering, the private sector is able to pay significantly higher salaries than local authorities making recruitment in the sector more difficult.

- There are some bespoke regional issues which need to be dealt with. For example, there are shortages in London in the public health sector.

Returners

1.45 We recognise the importance of enabling people who have had a career break to care for others, or who have lost their jobs, to return to work and bring their skills and experience back into the workplace.

1.46 Further returner programmes should be run in the future to prevent much-needed skills and experience being lost. The Return to Social Work programme has proved of great value during the COVID-19 response and other programmes are due to start for ICT and planning shortly.

1.47 With around £2 million annual funding in the next CSR period, the LGA would repeat these programmes and expand them to other areas where there are challenges in recruitment. For example, environmental health and other regulatory enforcement specialisms have been in high demand during the pandemic response and will continue to be central to renewal.

Registers

1.48 It has been evident during the COVID-19 response that there is a need for increased capacity in some key professions in local government.

1.49 The Social Work Together register (developed by the LGA, DfE and Social Work England) of available, qualified social workers was established early in the response to help meet the urgent demand for children’s social workers. It enables councils to identify potential individuals, who had been provided with necessary refresher training, at short notice.

1.50 So far, around 100 councils have signed up to Social Work Together, and over 1,000 social workers have shared their skills on the online platform and can access relevant training while they wait for councils to contact them about available positions. The social workers are a mix of those on the temporary and permanent registers, meaning they can support both short-term and long-term roles. Councils view the credentials of these individuals for free, avoiding the cost of agency fees.

1.51 Discussions with other government departments suggest an interest for similar projects for other professional groups who are already in high demand and/or will be needed to address EU Exit transition, for example regulatory services including environmental health and trading standards.

1.52 The LGA would like to work with Government to implement a similar model to Social Work Together for these professions to enable local authorities to draw on suitably qualified, available professionals. Each programme has annual costs of around £300,000.

Council pay

1.53 The Government has set a target for the National Living Wage (NLW) to reach two-thirds of median earning by April 2024. The current projection stands at £10.69 per hour by that date (an increase in 19p since the target was announced). The new Local Government Pay Spine was introduced in 2018 to provide a cushion between the lowest local government hourly rate and the NLW. Some differential between NLW and local government rates will need to be maintained, as well the differentials set between spinal column points on the national pay spine.

1.54 Allowing for some headroom to be retained and to accommodate the difficulty in aiming for an as yet unknown target in three years, it is reasonable to set a target for the lowest local government pay rate of £11 per hour by 2024.

1.55 Securing a pay agreement of 2.75 per cent in 2020/21 has helped reduce the cost for the next three years but it remains that case that, in order to have confidence to satisfy the NLW target and retain spinal column differentials in full, significant pay awards will need to be agreed in future years.

Local Government Pension Scheme (LGPS)

1.56 There will be significant additional administrative resources and system changes needed to implement the remedy required by the McCloud age discrimination case. It is estimated that the burden will be similar in nature to the introduction of the reformed 2014 scheme which according to combined annual reports for that year resulted in an increase in administration costs of £9 million per annum.

1.57 The potential impact of McCloud on actual pensions costs is estimated by Government Actuary’s Department to be worth £2.5 billion for the LGPS. This is in addition to the potential annual £600 million cost of the ‘cost cap’ changes to benefits, although there may be a degree of netting off between these two figures.

1.58 Further liability pressures already announced or expected include:

- the Goodwin age discrimination case, with estimated annual costs of £300 million; and

- the equalisation of Guaranteed Minimum Pension which a 2018 Deloitte survey estimated at an average cost of 0.7 per cent of liabilities. For the LGPS this would be just over £2 billion.

1.59 As council employees make up about 75 per cent of the LGPS, the pressures above equate to a risk of approximately £3.6 billion, in addition to £0.7 billion annual pressures from the revaluation of the pension funds which have been set out by the IFS in its recent work.

1.60 There are specific pay and pensions pressures related to fire authorities and teaching staff in schools and they are outlined elsewhere in the submission.

COVID-19 impact on local taxation

1.61 All of business has been affected by the pandemic. The shifts to home working and the enforced business closures have had an effect in the short term, with the long-term implications of COVID-19 not yet apparent.

1.62 Local government has played its part in responding to the pandemic and contributing to measures to help businesses. For example, councils have administered around £10 billion of business rates reliefs and distributed around £11 billion business grants.

1.63 Business rates were due to raise £25.6 billion to contribute towards local government services in 2020/21, both through retained business rates and amounts redistributed through the central share. That accounts for around a quarter of local government revenue spending, or up to 40 per cent if grants to education and the police (which are ringfenced or service-specific) are removed.

1.64 Following the measures announced in March 2020, 40 per cent of business rates in 2020/21 is being covered by retail reliefs (around £10 billion). However, business rates collection is likely to be down even despite the increased reliefs, with current predictions by councils suggesting a £1.6 billion shortfall to the public purse.

1.65 Prior to the pandemic, local authorities set their budgets on the basis of expecting nearly £30 billion of income from council tax, constituting over half of their core spending power. In the context of the current COVID-19 pandemic, the returns to the MHCLG monthly financial information survey for the months of April to July suggest that collection of council tax, in recent years over 97 per cent, could be reduced by 5 per cent to around 92 per cent.

1.66 It is welcome that the Government has already confirmed that councils will be able to spread the impact of local taxation losses over three years. However, the fact that councils will still have ultimately to cover these losses in the absence of Government funding contributes to the £5.3 billion funding gap in 2023/24 as outlined above. Having to deal with these losses at all will hamper the ambition and efforts of local government to improve services and energise the economy as we recover from the pandemic.

1.67 In its funding gap analysis, the IFS assumed that the impact on councils of the shortfall arising from irrecoverable uncollected local taxation in 2020/21, spread over the three-year CSR period to 2023/24, could amount to £602 million for business rates and £493 million for council tax, after netting off the funding already provided by the council tax hardship fund.

1.68 However, this is only one of the scenarios and is subject to great uncertainty because the COVID-19 pandemic is not yet behind us.

1.69 This uncertainty underlines the importance of the need for Government to guarantee that all local authorities will be compensated in full for all shortfalls in planned non-tax income and local tax revenues. This should include parish councils, which would both aid those councils and help principal councils who carry the liability for uncollected local taxation.

Council tax support

1.70 Local council tax support (LCTS) replaced the nationally determined Council Tax Benefit in 2013. This support has been increasingly withdrawn for working age residents. The Institute for Fiscal Studies found in 2019 that the most common level of minimum payment for working age recipients is 20 per cent – adopted by almost a quarter of councils. Another fifth have minimum payments of over 20 per cent.

1.71 One particular reason for this shift is that the central resources to support this have fallen by an estimated £2 billion since 2013/14 at the same time as councils were not able to vary the amount received by pensioners.

1.72 The number of council tax support recipients is rising sharply. Figures for the first quarter of 2020/21 reveals that over 2.5 million working age people across England claimed a discount on their council tax between April and June. That was an increase of 9 per cent from the same quarter in 2019, and the highest number for any quarter since records began in 2015-16. This is expected to be even sharper over the summer due to the continuing impact of COVID-19. The number of claimants may continue to rise in future years due to the knock-on economic impacts.

1.73 Work commissioned by the LGA from LG Futures estimated that the cost of the increased claimant numbers of LCTS due to COVID-19 could be £586 million in 2020/21 alone.

1.74 However, it remains to be seen whether the impact on LCTS costs in 2020/21:

- represents the highest point of the loss or, due to ongoing economic factors (i.e. longer term unemployment / recession), whether this cost will continue to rise over the forthcoming years;

- rises to a high point in 2021/22, as the full year effect of COVID-19 (post furloughing) hits the economy, before continuing to fall; or

- follows a different and unknown trajectory, given the unique circumstances around COVID-19.

1.75 As part of its medium-term outlook analysis, the IFS made a central estimate of the long-term impact on LCTS of the recession of additional costs of £123 million in 2023/24, with an upper estimate of £389 million.

1.76 This estimate is based on data from council returns to MHCLG about the extra LCTS costs in 2020/21 and links to future unemployment rates forecast by the Office for Budget Responsibility.

1.77 However, evidence suggests that council tax benefit claimant numbers were more responsive to unemployment rates during the last recession than councils’ current forecasts for 2020/21 suggest. Taking that past relationship as a proxy, we estimate that the extra cost pressures on LCTS in 2023/24 could actually be worth as much as £570 million, for a total sum impact of nearly £3 billion over the three-year CSR period.

1.78 It is clear therefore that this is another highly uncertain factor that needs to be monitored carefully as it can constitute a significant financial downside that is not captured by central IFS estimates.

1.79 During the last recession, council tax benefit was administered by councils but fully funded by Government in the same way as housing benefit. However, since the transfer to local government in 2013, this is no longer the case and a rise in demand for council tax support of this nature represents a significant unfunded burden.

1.80 If the additional costs of increased demand for council tax support are not fully funded, councils will have to absorb them through reductions in other services or by further cutting the level of council tax support to working age recipients.

1.81 The Government has committed to compensate councils for part of the losses of income from sales, fees and charges and to address the sharing of the impact of council tax and business rates losses between central and local government at the Spending Review. LCTS costs should be part of those considerations and as a minimum include full funding of the whole additional caseload.

Improving local taxation

Council tax reform

1.82 In England, council tax is based on 1991 property values and has not been revalued since then.

1.83 Most discounts and exemptions are fixed nationally. The mandatory single person discount covers almost 32 per cent of dwellings. This discount is not means tested. Other mandatory exemptions apply to students and others. Empty property discounts are discretionary.

1.84 Council tax increases from year to year are constrained centrally, originally through capping and now through centrally imposed limits over which a referendum would have to be held. In recent years the referendum limit has been 2 or 3 per cent with a further 2 or 3 per cent allowed for the Adult Social Care precept for adult social care authorities.

1.85 Council tax is only payable on properties classed by the Valuation Office Agency as dwellings. So, for example, there is no council tax payable on properties not on the list because they are undergoing reconstruction or rebuild. This can result in delays in councils being able to receive income from new or reconstructed dwellings after planning permission is granted, either because they are not built, or they are not valued immediately.

1.86 We would like to work with Government to deliver our three-point plan for making council tax more local:

- The council tax referendum limit needs to be abolished so councils and their communities can decide how local services are paid for, with residents able to democratically hold their council to account through the ballot box. This should apply to all local authority types. Failing that, the Government should consider ways to define the referendum limit which do not reward or penalise councils based on their past decisions. For example, the percentage-based limit could be replaced by a threshold which also allows higher percentage increases to areas with lower council tax levels, similar to the £5 flexibility provided to shire district councils.

- Councils should have the powers to vary council tax discounts to make sure the tax system is fair to everyone according to local circumstances. A prime example is the single person discount, worth 25 per cent of the total bill and applied to all households where there is only one liable occupant regardless of their ability to pay. This discount is worth £3 billion each year.

- To improve the build-out rates of homes with planning permission, councils should be able to charge developers full council tax for every unbuilt development from the point that the original planning permission expires, as opposed to having to wait for the Valuation Office Agency (VOA) to list them following their completion. LGA analysis suggests that over one million homes granted planning permission since 2010 have not yet been built. This is equivalent to three years’ worth of Government’s target number of homes to be delivered each year.

Business rates reform

1.87 As part of the Government’s Business Rates Review, the Government has acknowledged that business rates are an important source of revenue for local government and states that the impact on the local government funding system will be an important consideration in reviewing the tax. It is an important opportunity to take a fresh look at the business rates system as it is being stress-tested by the impact of the pandemic.

1.88 Above all, local government needs a funding system that raises sufficient resources for local priorities in a way that is fair for residents and gives local politicians all the tools they need to be the leaders of their communities. It is therefore important that the tax system, including business rates, provides as much certainty as possible.

1.89 It is widely accepted that taxes should adhere to certain principles of good design. Applied to the local government context, they are:

- Sufficiency – financing for local government services must be sufficient.

- Buoyancy – rises along with economic activity with protection for local government from losses in income given the need to support local government services.

- Fairness – the taxpayer makes a fair contribution and the taxbase is not too narrow.

- Efficient to collect - any tax should be efficient to collect; if the costs of administration and collection of a tax are high then the net yield will be lower than it would be for a more efficient tax.

- Predictability and transparency - income from a tax should be predictable and it should also be relatively straightforward to work out how the tax has been derived.

- Incentive – incentives should be provided to both business and local government.

1.90 Property continues to provide a good basis for a local tax on business. Business rates are efficient to collect and has been relatively predictable and buoyant in recent years. However, the changing nature of business alongside the nature of demand pressures on councils means that we cannot look to business rates to form such a substantial part of local government funding in the future and alternative means of funding councils will be needed instead or as well as a reformed business rates system.

1.91 Many fundamental concepts such as beneficial occupation have been set by case law and not by statute, leading to results which may seem puzzling to the public, such as the fact that large vacant sites may not pay business rates. We have proposed in our response to Tranche One of the Business Rates Review that the Government should bring forward changes in the basis of liability so that more is defined in statute. We continue to support such an approach, and how this is framed should be the subject of a further consultation involving the LGA and councils.

Business rates reliefs, exemptions and avoidance

1.92 The ability to give reliefs, both mandatory and discretionary, is determined by statute, central regulations and case law. The current reliefs system is very heavily weighted towards centrally determined reliefs.

1.93 If local authorities had more discretion over these centrally determined reliefs, they would be able to help local and independent businesses in order to stimulate the local economy. It would also allow councils to incentivise other behaviours that match local and national economic priorities, for example providing reliefs for new or green investments.

1.94 Due to the impact of COVID-19, up to 50 per cent of potential business rates will be covered by centrally determined reliefs in 2020/21 and it might not be possible to achieve the degree of local discretion outlined here immediately. However, the Government should take this opportunity to announce its intention of making most reliefs discretionary with the timetable for implementation to be discussed at a later stage, including how best this can be made fair for business and local government.

1.95 Currently local authorities are statutorily barred from giving discretionary relief to premises occupied by themselves or preceptors. This has become an issue particularly for public conveniences and for market traders. The LGA considers that this statutory bar should be removed.

1.96 The complex framework of business rates exemptions needs to be reviewed. This includes, for example, agricultural exemptions where there are businesses which should normally be rated but just happen to be located on farms. However, we are also aware that the agriculture sector has been hard hit by COVID-19.

1.97 Aggressive business rates avoidance continues to cost councils and central government around £250 million each year. We call for the Government to tighten up on the abuse of reliefs on the same lines as are proposed to come into force in Wales and Scotland in April 2021. Common specific examples of such business rates avoidance are:

- Repeated short term periods of occupation of six weeks or slightly more, resulting in a further period of exemption from empty property rates. This can go together with contrived reoccupation of property, for example by storing boxfiles, in otherwise empty warehouses as evidence of reoccupation.

- Misuse of charitable occupation rules.

- Misuse of insolvency exemptions, through the use of ‘phoenix’ or ‘shell’ companies which trade for a short while and then liquidate.

- Splitting properties in order to qualify for small business rates relief.

- Registering second homes as non-domestic properties to benefit from small business rate relief when the property is not genuinely available for letting. Although the Government consulted on tightening the rules in 2018, no action has been taken.

The business rates multiplier

1.98 Annual uprating of the business rates multiplier is an important source of stability of business rates income. Local government has received compensation for the move from RPI to CPI uprating, as well as new nationally introduced business rates reliefs, during the 2015 Spending Review period and the 2019 Spending Round and it would lose out if this were not to be continued. Around £1.3 billion was paid to local government in this way in 2019/20.

1.99 Any reduction in the buoyancy of business rates, such as including changes in rateable values from constructions, demolitions and alterations in the multiplier calculations at revaluations would be likely to result in a lower multiplier and thus lower income and would have implications for the buoyancy of local government income and business rates retention.

1.100 Local government should be able to set its own business rates multiplier, or at the very least be able to set a multiplier (p in the £) above and below the nationally set multiplier. Local authorities ought to have the power to vary multipliers by property value or property type. This would enable them, for example, to charge a higher multiplier to properties such as warehouses linked to e-commerce in order to support reliefs for other businesses.

Business rates and e-commerce

1.101 Online businesses pose a challenge to traditional businesses and to business rates as a tax. If an activity can be carried out online without the requirement for premises this will reduce the yield of business rates which goes to both central and local government. However, it may lead to other activities that will pay business rates, such as distribution warehouses or businesses which start off online and then decide to open physical premises.

1.102 Taxation should be fair for both physical and online businesses. In January 2020, we launched a report which looked at the potential for an e-commerce levy, which concluded that it is deliverable and offered a number of options on how it could be implemented.

1.103 We welcome the fact that the Government is consulting on proposals for an online levy as part of its business rates review, however the proceeds of such a levy should be retained by local government as a way to diversify the local taxbase and protect against further shifts in the balance between traditional and online retail.

Fiscal devolution

1.104 As outlined earlier in this submission, we strongly believe that delivering further public spending efficiencies will require services delivered by different Government departments to join up locally. To properly unlock the capability of local partners to cooperate, it is important to unlock freedom for public resources to be used more flexibly.

1.105 By opening a conversation about new forms of taxation such as the e-commerce levy and the land value tax, the business rates review provides an opportunity to move in this innovative direction.

1.106 The income to pay for public services at the local level should reflect service demand, should be buoyant and should allow taxpayers to hold decision-makers accountable on expenditure and tax decisions made in their local areas. It should also be sufficiently diversified to guard against shocks and unringfenced to allow for flexible deployment across boundaries of public services and providers, both for capital projects and day-to-day spending.

1.107 Local assignment of taxes can provide areas with incentives to strengthen the local economy as well as create a more diverse funding base, less dependent on central government decisions. It would also allow public sector partners to make collaborative decisions on stewardship of local public funds.

1.108 Recently published research compared levels of fiscal devolution between the UK and three other European nations (the Netherlands, Germany and Switzerland). It found that local governments in these countries have greater revenue raising powers and retain more of their funding locally.

1.109 In addition, econometric analysis drawing on the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)’s fiscal decentralisation index highlights the extent to which the UK is an international outlier and argues that if the UK moved to the OECD average for tax decentralisation, all regions of England could see a gain in GDP, with an average of 1.79 per cent increase. Currently only 4.9 per cent of taxes in the UK are set locally, whereas the OECD average is 15.1 per cent.

1.110 One way to achieve further fiscal decentralisation would be to assign each local area a proportion of nationally collected taxes paid by citizens in a given area. It would be for local politicians in partnership with local providers to decide on priorities and the allocation of funding. Equalisation would be built into the apportionment formula to account for relative needs, but even so there would be a greater degree of fiscal independence, with areas spending the taxes raised in their communities.

1.111 Assigned taxation is just one option and the right mix of taxes and services should be subject to a full national debate. Some areas will want to think further about options for rebalancing local and national taxation. They will be seeking the freedom to collect different taxes in different ways to support local priorities, or introduce new local levies, such as a tourism tax.

1.112 In the long term, the finance system needs to accommodate the ambition for devolution, which encompasses the full range of public services delivered at the local level. This approach to funding local public services would require a substantial rebalancing of decision-making in England and would put English local government as a whole on the same footing as the devolved administrations.

Capital investment

1.113 Investing in infrastructure through the use of capital spending will be crucial to delivering the social and economic recovery from the pandemic, delivering key government priorities on housing and regeneration, and making the public sector more efficient and able to deliver better value for money while providing key services for citizens.

1.114 The Government has recognised this by prioritising ‘project speed’ and a commitment to the National Infrastructure Strategy. Councils are best placed to deliver on much of this agenda, if given the right financial freedoms, flexibilities and support. The Comprehensive Spending Review is the right place to address this.

1.115 Throughout its five chapters, our submission contains many examples of where councils can play a key role in delivering priorities, such as fixing the nation’s roads and delivering economic regeneration, delivering high speed broadband and high-quality mobile connectivity everywhere, investment in housing (coupled with reform of Right to Buy), schools, transport infrastructure, as well as tackling environmental challenges including reforms to waste and recycling as well as carbon reduction, and investment in digital infrastructure both to improve local areas and enable better service delivery and more efficient ways of working. The future arrangements of the UK Shared Prosperity Fund (UKSPF) are also vital.

1.116 But in order to deliver, councils need the right general financial support and framework.

1.117 Government grant funding of council capital programmes has reduced in recent years. Capital funding in 2018/19, the last year for which outturn figures are published, was £600 million lower than in 2014/15. If 2014/15 levels of grant had been maintained councils would have had an additional £2 billion to invest in local capital projects between 2014/15 and 2018/19.

1.118 Where government capital grant funding is available, it is frequently fragmented and accompanied by bureaucratic and burdensome bidding processes. For example, there are at least 11 different capital funding streams for roads investment alone, each with their own arrangements, rules and allocation processes. Councils have frequently had to consider the risk of investing significant time and revenue resources that cannot be spared into long-winded processes that are not guaranteed to deliver any local benefits. This is something that the Green Book levelling up review should address.

1.119 A further funding freedom can be delivered very simply, and at no cost, by making the flexible use of capital receipts arrangements permanent. Government first introduced this flexibility in 2015 and now extended it to 2022. The Comprehensive Spending Review is the opportunity to make this permanent, adding certainty and removing the need for further review.

Borrowing framework

1.120 Instead of uncertain, diminishing and fragmented government capital funding, councils have been relying on their own resources, and on funding capital through borrowing funded by local sources of revenue under the prudential regime; this has often skewed capital investment into schemes that generate revenue as being the only ones that can be afforded while overall revenue funding has been reducing.

1.121 The prudential borrowing framework enables councils to source capital funding based on what is affordable and prudent, but otherwise free from external restrictions. A major part of that prudential assessment is having sufficient ongoing revenue funds to service the cost of borrowing undertaken.

1.122 The main source of borrowing for councils is the Public Works Loans Board (PWLB). This has largely worked well, although the decision to raise interest rates by 1 per cent across the board in October 2019 has had a major impact on councils. At a stroke this increased significantly the revenue costs of any new borrowing and therefore, of any new capital programmes being planned. In response councils were forced to reconsider the viability of several vital projects including projects to build new housing, investing in infrastructure to enable new housing developments to take place, and regenerating town centres.

1.123 Councils have either delayed investment or, where borrowing has still been undertaken, this has meant increased costs to councils which they have had to pay either to HM Treasury or to private loan providers if they have been used instead. The specific discounted loans schemes announced in the spring budget are helpful, but the overall rate rise needs to be reversed.

1.124 We are concerned that Government plans to change the lending terms for the PWLB by linking restrictions to all borrowing in any one year to individual investment activity undertaken by councils (even if not funded by borrowing) will make it harder for councils to borrow from it to fund priority capital schemes. It will also place PWLB officials in the position of adjudicating decisions that are a matter for elected councillors.

1.125 The problem caused by these practical issues was confirmed in a series of workshops run by HM Treasury over the summer for experts from local government. The outcome of the consultation is likely to be published alongside the spending review and we call on the Government to address this practical problem when framing the new lending terms as well as reversing the interest rate rise announced last October.

Reforming the Green Book

1.126 HM Treasury has been conducting a review of the Green Book - guidance on how to appraise and evaluate policies, projects and programmes - used across Government to assess capital investment. This review was announced in the spring Budget and is seen as central to delivering levelling up.

1.127 The Review has been undertaken by officials and officers from the local government sector have contributed comments to the review team. The outcome of the review and the new Green Book are due to be published before or as part of the Comprehensive Spending Review.

1.128 The announced aim of the review in the Spring Budget is to make sure that government investment spreads opportunity across the UK. It will aim to do this by improving the decision-making process with better information especially around levelling-up, improve public and stakeholder confidence in different parts of the country and embed the right culture and data to develop and appraise policies to support levelling up.

1.129 The review presents an opportunity to change the way the Government views local capital investment and in doing so enable investment to be managed better locally delivering benefits across the board.

1.130 The way in which the Green Book methodology is used should be changed to take better account of local circumstances. At present, the guidance places great value on national financial factors, but in a narrow way. For example, it encourages business cases to be developed in isolation from local strategies and not to consider impacts on local places. It does not encourage local factors and local place-based impacts to be taken into account.

1.131 This has significant implications for levelling up and means that local place shaping factors, that can often have significant local financial and social consequences, are often ignored.

1.132 Consolidation of the current fragmented funding arrangements, particularly when they relate to capital, is clearly the best solution, coupled with greater devolution of decision making to the local authorities.

1.133 However, there are amendments that can be made to the Green Book methodology that can also help. For example, a simple change would be to make a local impact analysis mandatory for all projects reviewed using the Green Book. At present local impact analysis is optional.

Driving efficiencies using investment in digital solutions

1.134 Further capital funding is required to level up digital solutions and opportunities that will improve services, enhance accessibility and connectivity, improve security and deliver efficiency for local authorities through innovation, channel shift to online services and maximising the productivity of the workforce.

1.135 These innovations are numerous and are not exhaustive but could consist of the projects that focus on predictive analytics, artificial intelligence (AI) bots, self-serving initiatives, e-forms, Internet of Things networks, improved CRMs, smart place applications, online resident portals, syncing IT legacy systems and better use of digital platforms.

1.136 In order to have maximum impact the opportunity to develop similar solutions must be made accessible to all councils. The Government should fund councils to enable them to support digital inclusion and closing the digital divide by investing in improving the digital skills of local communities to encourage more people to pursue digitally focused jobs.

1.137 Additional dedicated investment should be made in emerging digital infrastructure and connectivity with councils playing a key role in the development of these networks to shape and strengthen opportunities for residents and businesses as new ways of working become the norm. This will reduce carbon emissions and boost economic viability across the country. Research in this field suggests that a programme of £130 million over four years would help contribute to fixing the digital divide and levelling up the economy through digital skills.

1.138 Over recent years councils have proven they are up to the challenge to develop digital solutions that harness emerging technology, build inclusion and enable connectivity in their localities where further support and investment needs to be made to ensure the momentum developed in response to COVID-19 is maintained and grown.

A long term settlement for local government improvement

1.139 Sector-led improvement (SLI) is an approach put in place by councils and the LGA to support continuous improvement.

1.140 The approach was inaugurated in 2011, providing an alternative to the top-down and bureaucratic national performance framework which it has been estimated cost the government nearly £2 billion a year. In contrast, MHCLG provides annual grant of less than £20 million to support sector-led improvement.

1.141 The approach enables councils to improve themselves, is consistent with the principle of local accountability for results and pays for itself several times over. Verified savings of over £40 million per year are achieved and the exact figure is certain to be significantly higher than this, arising from uncosted efficiencies and indirect benefits.

1.142 There are many advantages to sector-led improvement, not least its flexibility. In the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, the offer was revised to provide relevant support to councils responding to the crisis and is now also providing tools and materials that will aid councils through the recovery. Throughout lockdown, development work on the climate change and digital security programmes has continued at pace.

1.143 There is also evidence that sector-led improvement reduces the risk of intervention in councils. To date there have been seven statutory government interventions in English local government under the Local Government Act 1999, five during the first 10 years after the Act when statutory inspection was in place and two in the 10 years since Audit Commission inspection was discontinued (Rotherham and Northamptonshire), despite the fact that these last 10 years have been a major financial challenge to councils compared with the previous ten.

1.144 The record of sector-led improvement is impressive, but it could be further enhanced if the grant from MHCLG was awarded on a multi-year basis. As a recent independent review of SLI by Shared Intelligence concludes, the current annual grant settlements drive a short-term focus constraining both the impact of SLI and the sector’s ability to evidence that impact. This is not compatible with the reality that action to influence councils’ effectiveness, improvement and innovation is not a quick fix. The annual cycle also mitigates against securing meaningful sector engagement in shaping the SLI offer.

1.145 A longer-term settlement for sector-led improvement would facilitate a longer-term view of the impact of sector led improvement. This would allow SLI to deliver outcomes planned over a longer timeframe, giving councils the certainty they need that sector led improvement will be there to support them over the next three years.

1.146 We call for a three-year settlement for sector led improvement for councils: £70 million over the course of the spending review period to allow this vital work to continue.

Care and health inequalities

Adult social care

2.1 Social care plays an essential role in supporting people to live the lives they want to lead. Before the COVID-19 pandemic this role was often invisible and a submission to a spending review would have had to champion the value of social care.

2.2 The pandemic has changed this. Social care, and crucially its value to people and wider society, is visible to all like never before. Daily media coverage has shown the public the extraordinary lengths the care workforce has gone to in keeping our loved ones safe and well, often sacrificing time with their own families to do so and always wary of the risks they are exposed to. Politicians from all parties have paid tribute to the workforce and the Government has stated that, as a nation, we are indebted to their selfless dedication.

2.3 In just a few short months, the pandemic has revealed to the public at large both the strengths and value of social care, and its many challenges.

2.4 Even before the pandemic, adult social care was under significant financial pressure.

- The squeeze on council budgets has resulted in some adult social care providers being in a perilous state. The IFS has estimated that the pressure on the provider market, resulting from councils paying less than a sustainable rate on commissioned services, is worth £1.34 billion on the basis of most recent data. Over time, if unaddressed this can grow to as high as £1.7 billion due to demand and inflation pressures. This is in line with our past analysis.

- LGA analysis before the pandemic showed that adult social care costs were projected to increase by £1.3 billion each year from 2019/20 to 2024/25 simply to maintain 2019/20 levels of access and quality, but factoring in demand and inflationary pressures, such as the NLW. This included demand pressures for both older and younger adult cohorts. IFS analysis suggests a similar estimate for annual cost pressures.

- Councils received 1.91 million requests for support from new clients in 2018/19, up from 1.84 million requests in 2017/18. Age UK estimates that there are 1.4 million older people who do not receive the help they need.

2.5 The legacy of COVID-19 for social care – and most importantly the people who use social care services – must therefore be a reset, not simply a restart.

2.6 This impetus should spur our thinking around long-term reform of care and support, which we have always said should be built on cross-party cooperation. We are committed to working with Government and all parts of the social care world – particularly those with lived experience – on a way forward that is informed by the many valuable lessons from the pandemic on the role and value of social care in all our lives.

2.7 The Comprehensive Spending Review provides a crucial opportunity to begin that process. It must act on three main fronts:

- provide additional funding to shore up social care ahead of winter and a likely second wave of the virus, with a look to this continuing in future years;

- provide additional funding for the medium term to help address the long-standing challenges that have faced social care, many of which have been exacerbated by the pandemic; and

- use the above funding as a ‘down-payment on reform’ and to pave the way for changes that will finally put the funding of social care on a sustainable footing for the long-term.