Executive summary

The value of good nutrition for the early years extends beyond physiological health – it contributes to establishing social behaviours, supports learning, and influences food preferences and eating habits. It underpins growth and development, can help to reduce childhood obesity and is a building block of the first 1,000 days of a child’s life.

This report focuses on nutrition in early years settings. According to data from Gov.uk 92 per cent of three to four year-olds are registered for under five education provision in England. Early years is an important stage of a child’s life between age nought and five. Bremner & Co were commissioned by the Local Government Association (LGA) to capture learning from councils across England about nutrition in early years settings. This report examines the relationship between councils and all early year settings - maintained, Private and Voluntary Institutions (PVIs) and childminders. It comes at a time when the early years sector is calling on government for more funding, increased resources, and better guidance. The LGA is also calling on the government to increase funding for this area.

The government recently announced childcare reforms - from September 2025 all children of working parents from the age of nine months upwards will be entitled to 30 hours of free childcare. The government priority is to support working families, which may also have a disproportionate impact on children living in disadvantage. For food provision, it means that children in the early years will be getting a greater proportion of their nutrition in settings, raising a pertinent question: is food of adequate nutritional quality and how confident can we be about early years nutrition data?

About this report

This report is an overview of how some councils in England see the challenges, barriers and enablers to good nutrition in early years settings. It comes at a time when resources in early years teams across councils are stretched, and when incoming childcare reforms mean more young children will be in settings across the UK from September 2025. Little is known about what children are fed in early years settings. Guidance is voluntary. Monitoring and accountability are minimal.

Close to 1.7 million under five year-olds are registered for either the 15- or 30-hour government entitlement. This means there are 1.7 million young children to feed with little oversight of what they are being fed. The mandatory school food standards don’t apply and the voluntary guidance, Eat Better Start Better (EBSB), was last updated over seven years ago. Questions have also been raised over EBSB’s relevance and applicability twelve years on and its cultural appropriateness. The recent summary report by the Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition (SACN, July 2023) also highlighted that the larger portion sizes of meals and snacks provided by early years settings are linked with higher energy and food intakes.

The National Child Measurement Programme (NCMP) indicates that 22 per cent of children under the age of five are overweight or living with obesity. This is often considered a ‘school problem’ but what happens in those nought to five years are crucial to understanding this statistic and moving the dial.

The LGA commissioned Bremner & Co (an independent child health and nutrition organisation) to produce this report focused on the barriers and enablers to good nutrition in early years settings from the perspective of councils. 12 early years leads from five councils in England were asked about what challenges they face in working to improve early years nutrition.

Key messages

- The childcare and early years providers survey found there are 1.5 million children registered to attend an early years setting in England.

- The food they eat in settings greatly contributes to their daily intake of calories – for school food this is estimated to be 30 per cent of their daily calories according to a National Library of Medicine report.

- Nutrition indicators, such as dental caries and obesity rates, provide an indicator that children’s diets from nought to five may not be supporting their health in an optimum way.

- Some councils tell us that early years nutrition is often not on the agenda; it is often overshadowed by school food and that there is a lack of political interest in this area.

- Councils indicated that capacity for supporting early years settings has diminished. Many councils had early years nutrition programmes focused on settings, but these were ceased during Covid and have not been re-established.

- Settings report doing the best they can with insufficient funding, stretched resources and managing the cost-of-living crisis. Many go above and beyond to feed disadvantaged children who do not meet the criteria for funding. Some seek support from community organisations such as FareShare to donate food.

- Many councils focus their efforts on early years nutrition in the maintained sector, however, a Department of Education survey found 77 per cent of nought to five Childcare provider places are in PVI or childminders settings, with only 23 per cent in maintained.

- There is a data gap around whether food served to children in settings meets their nutritional needs.

- In councils, where good practice exists, it is supported by funding, engaged teams, strong political interest in this agenda and good data. Matrix working and engaging stakeholders in a collaborative manner is core to progress. A comprehensive nought to five strategy that incorporates nutrition, mental health, and physical activity helps early years development and growth.

- There are challenges to overcome, but also many innovative examples of where councils and settings are striving to meet standards and deliver well-rounded nutrition in the early years.

Context

In 2021, the Obesity Health Alliance established a vision for early years in the Turning the Tide report. The report stressed the importance of early years as an opportunity to start young children on a healthier weight journey. It also argues that the UK government needs to create a fully funded system that facilitates good nutrition and health. It put a spotlight on what it referred to as ‘institutions,’ such as early years settings, and their potential role in fostering healthy behaviours that continue outside the home.

Unlike the school food standards, the guidance for the early years sector - the Eat Better Start Better guidelines and the example menus from the former body Public Health England – are voluntary. Research indicates that children in nurseries eat many high-sugar or high-fat snacks, and a low proportion meet the standards for fruit, vegetable, and oily fish consumption.

Ofsted is the single policy instrument for monitoring nutritional quality in EY settings. All early years providers in England have a mandatory obligation to follow the early years foundation stage framework, which states that “where children are provided with meals, snacks and drinks, they must be healthy, balanced and nutritious”. Councils interviewed for this report stated that the Ofsted reports they access have limited information on nutrition.

Maintained settings represent only 23 per cent of the available early years childcare places and this is often where councils focus their efforts. The removal of sufficient funding for early years teams means they have insufficient capacity to cover PVI’s, and childminders. Councils do not often have authority or accountability for PVI’s, their role is to passport funds from central government. Further to that, engagement with settings is often triggered by a report of an issue and is therefore an intervention vs. prevention approach.

Finally, there is a dearth of data. There is almost no research to indicate the quality of food in early years settings. A recent independent report published by the Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition (SACN, July 2023) into feeding young children aged 1-5 identified “a number of significant gaps in the evidence relating to infant and complementary feeding, as well as limitations in the study design for some of the available research.”

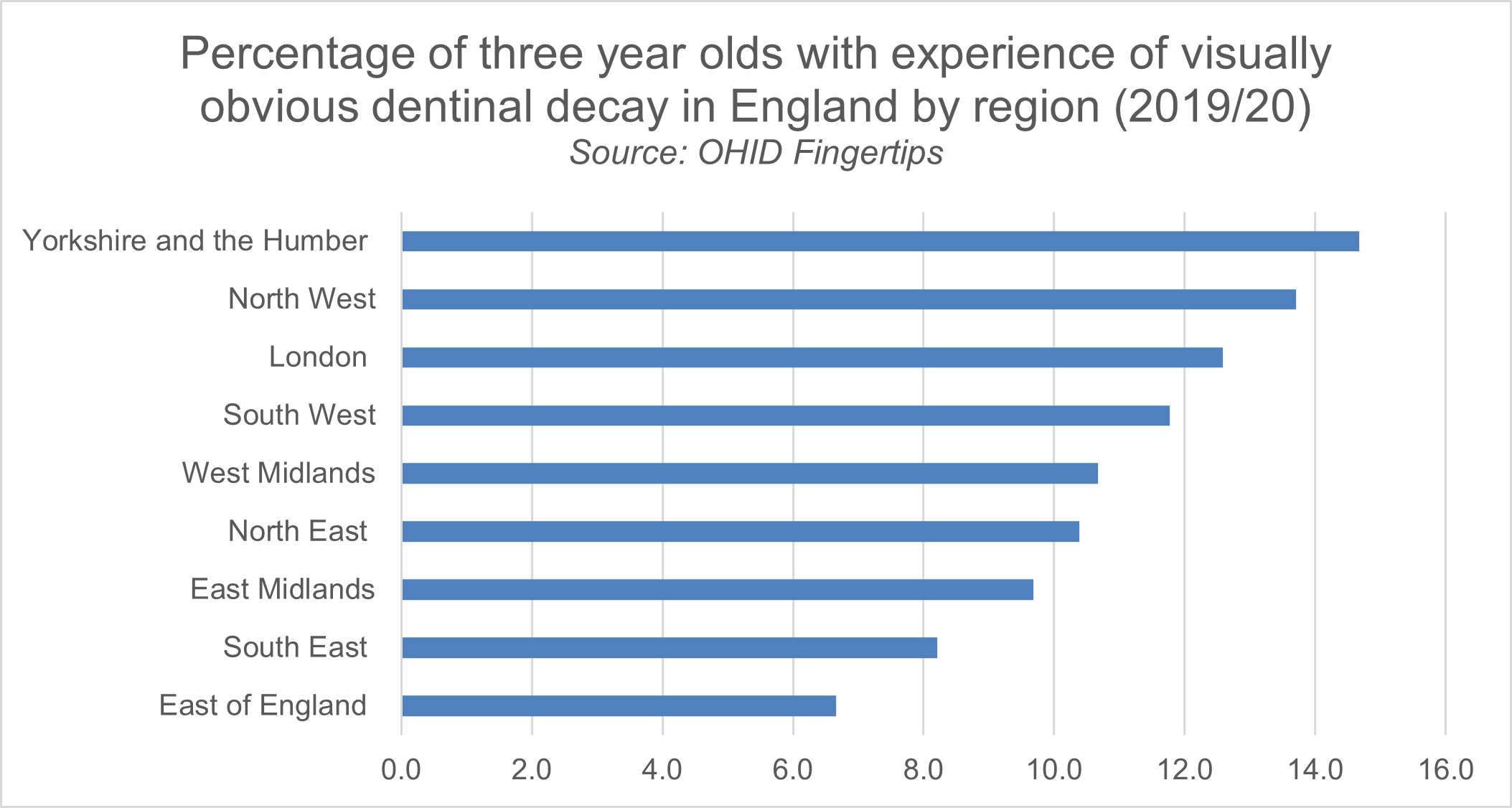

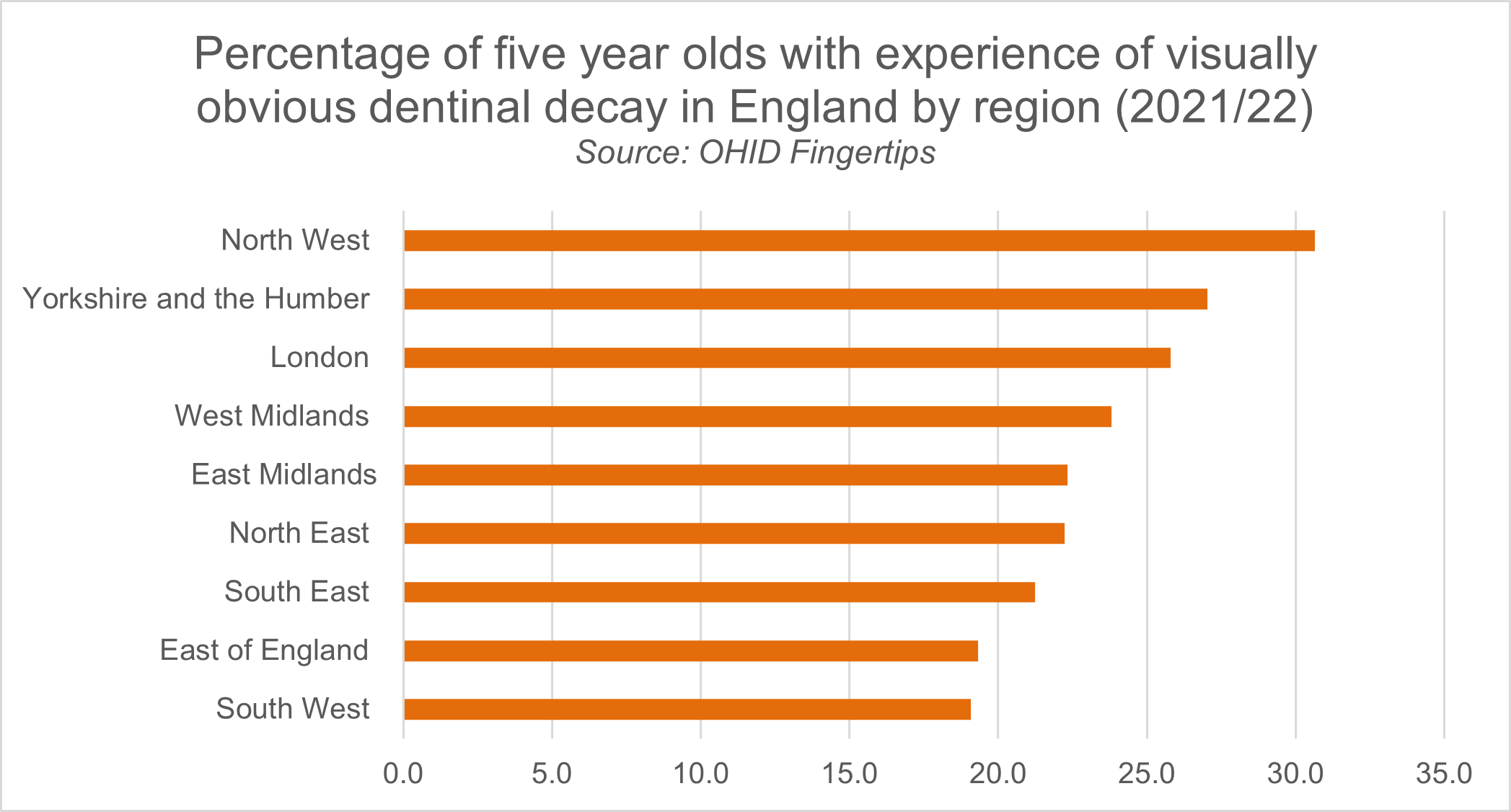

What we do know is that the incidence of dental caries for young children (tooth decay largely caused by dietary sugars) is concerning. In England, between the ages of three and five, the average percentage of children with experience of visually obvious dental caries increases from 10.7 per cent to 23.7 per cent. Regional variation exists; in the Northwest of England it rises from 13.7 per cent amongst three year-olds to 30.6 per cent of children aged five. This, combined with a quarter of our under-fives living with obesity, with higher rates in disadvantaged areas, paints a worrying picture.

Figure one illustrates the percentage of three year olds with experience of visually obvious dentinal decay in England by region (2019/20).

Figure two: Chart showing the percentage of five year olds with experience of visually obvious dentinal decay in England by region for 2021/22.

What councils have said

Is early years nutrition on the agenda and do councils have capacity and funding to engage in the early years?

Time to raise up early years on the child health agenda

School food is much higher on the agenda. Councils thought that there were ample opportunities to discuss school food policy and practice, and school food leads existed within authorities to champion the issue. Early years nutrition lacks a home within councils. early years leads in some councils said:

It's not a regular slot on the agenda.”

There is no portfolio lead. There is no designated lead.”

The team doesn’t exist anymore.”

Funding for early years in councils

The Centre for Social Justice reports that public spending for children under five is five times less than that for secondary school children and that in the past ten years, council spending on early years intervention has decreased by close to 50 per cent.

The councils we spoke to highlight how significant funding cuts have had an impact on their ability to engage in the early years nutrition agenda. This has been exacerbated by Covid and many nutrition programmes have been put on hold. One council had their early years team reduce from twelve employees to three. This means that implementing cross-cutting interventions or looking at preventative measures is difficult. There is a focus on safeguarding, welfare, and early intervention because it is a statutory duty. Many teams were limited in their ability to discuss their early years nutrition:

That's bad though, the fact that I'm not able to answer any of your questions anymore, because it isn't statutory duty for us. Prehaps it should be, perhaps it needs to be. If it were a statutory duty, I would be able to comment.”

The lack of early years nutrition leads hampers the ability to drive forward progress in early years nutrition. This means that for many councils, involvement in nutrition is with a setting is stimulated by an Ofsted report, or anecdotal feedback on nutrition quality, and therefore involvement is intervention vs. prevention-led. There was a strong desire from the early years teams to be involved in nutrition, but a lack of resources and too many competing priorities within their councils to facilitate it:

We've got much higher rates of excess weight in our reception than we have in our year six compared to England. We really want to be focusing on early years. Some kids spend so much time in early years settings and I have no time to focus on that. Because, you know, I get pulled in so many other directions.”

Settings did have a lot of intervention and were supported - HENRY and all sorts of other initiatives. And then no funding meant staff weren’t able to support. I think there was a lot of very good practice going on previously. I think then you know, poor quality food kind of just becomes more acceptable.”

We're very focused on early learning and development. That's what my team are responsible for. We used to have a safeguarding and welfare team; early years nutrition would have been something that they would have focused on - supporting settings with that. The team doesn't exist anymore.”

Many settings report to councils that maintaining food quality is difficult in the face of government early years funding, the cost-of-living crisis and recruitment issues.

Funding

Settings echo councils concerns about funding rates. With stretched budgets, settings are not always able to recruit dedicated kitchen staff and rely on existing untrained staff members to cook meals. While local and seasonal food would be a preference for many settings, this is not a feasible option, with most purchasing food from supermarkets or relying on alternative community groups such as FareShare to donate food. There is no specific funding stream for early years nutrition, and there are significant variations in the proportion of the total costs spent on food. This may be further impacted by upcoming childcare reform.

Figure three: Childcare and early years provider survey: Breakdown of provider costs

| Staffing costs | Rent or mortgage payments | Materials such as; books, toys or equipment |

Training costs | Food costs | Other costs | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| School based providers offering nursery | 85% | 1% | 5% | 2% | 1% | 6% |

| Maintained nursery schools | 82% | 1% | 2% | 1% | 1% | 13% |

| All school based providers | 85% | 1% | 4% | 2% | 1% | 7% |

| Private group-based providers | 72% | 11% | 3% | 2% | 4% | 7% |

| Voluntary group- based providers | 81% | 7% | 3% | 1% | 2% | 6% |

| All group-based providers | 76% | 9% | 3% | 1% | 3% | 7% |

Source for figure three: Gov.uk Childcare and Early Years Provider Survey

Councils also highlighted the inequity in funding distribution. Nursery pupils can only access free school meals if they attend a maintained setting and if they attend both before and after lunch. In many cases, children who might be eligible for free school nursery meals only attend for 15 hours per week, so they miss this nutritional support. It also creates a postcode lottery with access to free school nursery meals only for those who live in proximity to a maintained setting. It also means disadvantaged children may be missing out:

So, even though there is a free school meal policy, the fact is very few schools have access to that.”

Cost of living

Evidence suggests that across the country, all nursery settings are affected by the rising cost of food. In a recent study by the London Early Years Foundation (LEFY) and the Early Years Alliance, 94 per cent of the settings said that their food provision was impacted by food inflation, 62 per cent were using cheaper ingredients, and 65 per cent passed on the cost to parents. Settings require parents to bring in food from home, despite knowing that some may be of lower nutritional quality. 49 per cent of the participants reported evidence of food insecurity in families. The councils interviewed in this study echoed this concern:

We have had a few schools where they were offering hot meals and it's becoming unsustainable for them due to low numbers.”

Settings have to make really difficult decisions in terms of maintaining quality.”

So, I think we've seen that the quality of some of the food isn't as good as we would like it.”

Early years recruitment crisis

The recruitment crisis in the early years sector has had a demonstrable impact on the ability to offer consistent nutritious food. A recent report by the Early Years Alliance indicated that nearly eight out of ten providers found it difficult to recruit staff, with almost half having to limit the number of places or stop taking on new children. Settings deliver provision under significant resourcing pressure, which means good nutrition can fall off the agenda, and standards can slip. This impact was echoed across the councils. There is concern that upcoming changes to staffing ratios – with an increase in children permitted per staff member – will further exacerbate issues:

The early years sector is on its knees currently and you can't fail to have noticed things that have gone on in the press recently. And the proposed changes and the possible impact that that might have. They are struggling massively with recruitment.”

The LEYF study shows a strong desire by settings to provide good, nutritious food and shows how settings are using creative ways to tackle the barriers, such as cutting craft supplies to pay for food, which simultaneously limits play and development.

The private and voluntary childcare sector is often outside of the remit of councils

For the councils we interviewed, resource constraints means that they put a lot of their focus on maintained settings. While data on the exact number of children in settings is unavailable, statistics from a Gov.uk Education provision: children under five years of age report shows that 65 per cent of childcare places are made up of PVI’s, 12 per cent of childminders, and 23 per cent of school-based nursery places:

We wouldn't know what the PVIs work towards either, it would be down to them to, to decide on what their offer was.”

I would like to say that all settings provide healthy snacks. But again, this isn't something that we monitor.”

For two of the councils, Ofsted reports were scanned to review areas of concern in PVI settings, however many said that they are not seeing nutritional feedback on reports:

A setting said, ‘well, we've just got good from Ofsted, and they didn't say there was anything wrong with our menus.’ And it wasn't until I looked at them - the main meals and the snacks and there was an insufficient amount of vegetables.”

Ofsted are clearly not making recommendations about healthy eating because if they were that would be coming through on all their reports. I don't think Ofsted are having a good look at people's recipes and people's menus.”

Early years nutrition – where is the data?

Dental caries data and obesity metrics give an indication of need and nutritional outcomes, but there is little visibility of food input. Most data on the nutritional quality of breakfast, dinner, and snacks are observational; there are no food audits or monitoring of EBSB guidance. Some councils actively want early years metrics to be published and mandated within the Public Health Outcomes Framework – if that were the case, then the statutory responsibility would facilitate greater involvement:

Why aren’t these in the Public Health Outcomes Framework and then we can all compare ourselves to each other? That's what we do. Why not? I'm pretty sure the answer is because then Public Health would be accountable for food, and that suddenly changes Public Health grant and that whole system. So, there is this wilful gap around food as a national issue.”

Children aged around two to two and a half years old have important checks – the two to two-and-a-half year's health development check with a health visitor or nursery nurse, a 24–36-month check within their setting and the reception baseline assessment in schools. Councils informed us that these data sets are often not aligned or easily accessed, and for the early years check in settings the obligation is only to undertake it, make parents aware, and signpost as necessary. It is unclear to what extent nutrition forms part of this, where the data goes, how it is used and by whom:

The Healthy Child programme generally sees a child up to age two and a half, and then they're in nursery and they fall between those gaps. There is no nationally collected assessment in between age two and a half and five.”

Across all councils, the lack of data increasingly hampers their ability to progress in early years nutrition; it is a frustration and means they are often working in the dark:

We have issues in accessing the data. I'm not sure we collect the data in that format.”

We think it is covered but we don't have any evidence.”

It's really difficult to know what the quality is like.”

One council did have oversight of packed lunches within settings, which is an important area of focus as some settings do not offer food. There is useful guidance from First Steps Nutrition Trust on packed lunches for one to four year olds:

We have a high number of sessional nurseries but in most cases, they do not offer food...I know that all of those settings will share that they will have a clear policy in place, and they will recommend specific nutritional sort of meals if you like or recipes. I know a lot of them share information with families, and they specify which foods are allowed and which foods are not in terms of healthy eating.”

What is the best way of communicating and engaging with settings?

Councils informed us that they regularly send out bulletins, e-newsletters and signpost to relevant government communication on oral health or sugar reduction. However, some suggested that they do not know how well information is received, whether it is read, or if it is useful.

We focus largely on sharing information and signposting.”

I feel like we're feeding them the information that we get, but we don't know how useful that is to them.”

Settings indicated that in addition to their existing responsibilities, this information can be overwhelming, making it difficult to determine what should be the priority.

There’s too much information. There's information here, there's information there, there's information saying children should be eating more fruit and vegetables, then sugar swap instead, or change to sweetener or low sugar instead. There are too many things to be aware of.”

Many councils have found that self-accreditation schemes are useful for building relationships with settings. This comes in various forms, such as a healthy child mark or council-approved award schemes. Settings are required to self-complete a nutritional and healthy eating questionnaire, which is then verified by councils. Some barriers exist such as difficulty incentivising settings to take part, and the resources required on both sides to implement.

Innovative practice: Case studies

Where innovative practice exists, it is supported by funding, engaged teams, strong political buy-in and good data. Matrix working and engaging stakeholders in a collaborative way is core to progress. A comprehensive nought to five strategy that incorporates nutrition, mental health and physical activity helps progress early years nutrition. Two of the councils we spoke to share some of their strategies for raising the agenda in the early years – one highlights the importance of an early years vision, political commitment to this agenda, and strategy, and the other shows the innovative ways councils can engage with settings.

Case study: Westminster's nought to five pathway and integrated offering

Westminster council works to a set of core principles for their early years offer:

- Multi-stakeholder partnerships and matrix working.

- Strong political buy-in and interest in the early years agenda and investment in early years resource within the council.

- A 0-5 strategic partnership group which is embedded in the council.

- Good use of data and metrics to monitor performance.

Westminster takes a whole-system approach in the early years – they involve the settings, partners and residents, but also look at wider systemic drivers of poor nutritional outcomes such as the food environment, food access and the cost-of-living crisis. Political commitment in the early years is driven by very passionate Cabinet members. This is matched by investment in the early years, which is seen as a priority across the council. They have a cohesive early years policy and consider the life course of the child from to 0-18:

As well as obesity or mental health, one of our priorities here is for 0 to fives to have the best start in life. So, there's no friction - we're all going in the same direction. It's embedded within the council. We have some really passionate Cabinet members.”

A pre-birth to five strategic partnership group is something really useful to introduce and establish because I think bringing key agencies and partners together to have these discussions in a much more joined up type of way enables us to identify strengths and any gaps in services.”

Westminster has a team of early years advisors who support both schools and early years settings. They also have a continuous professional development coordinator whose role is to support training in early years.

Westminster has had a long-standing healthy early years programme (funded by the public health team) for the past ten years. What also differentiates Westminster is that they look at all settings – maintained, PVIs and childminders – to ensure they have a comprehensive picture of the nutritional offering:

We are the first council to include the PVI sector, and we were very clear that we wanted to include them. It ensures fairness, it has a fair access element.”

Westminster Council provides information to parents, trains staff in healthy eating, uses a nutritionist to review food menus and suggest improvements. They also look at the early years through a wide lens, considering physical, mental and emotional health.

They partner closely with their data intelligence team on a dashboard of early years metrics so that they can review progress, working across the council to use expertise from all areas. They also conduct review visits to settings and probe specifically on nutrition and the promotion of healthy eating in settings.

The council has developed a strong knowledge of its setting make-up – many settings are sessional and therefore do not provide food, meaning parents would be bringing in packed lunches. The council prepares for this by working with settings to implement a packed-lunch policy.

Westminster used the Beyond Boundaries framework to drive progress in early years. This framework was created by London Councils and has a self-evaluation reporting tool that helps councils and their partners reflect on how to integrate early years systems into their work.

Case study: Nottinghamshire’s Childhood Obesity Trailblazer programme

Nottinghamshire's Child Obesity Trailblazer programme was part of a wider national initiative funded by the Department for Health and Social Care (DHSC) and managed by the LGA with support from the Office for Health Inequalities and Disparities (OHID) between 2019 and 2022. The team in Nottinghamshire focused their Trailblazer work on families with children in their early years. The programme was wide-ranging, covering multiple cross-cutting objectives outlined in the the table below.

| Number | Activity | Deliverable |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Children's centres as a community food asset | Food clubs |

| 2 | Development of family meal/recipe box concept | Healthier @ Home meal kit |

| 3 | Increase Healthy Start vouchers uptake | Healthy start vouchers |

| 4 | Affordable healthy meals offer for childcare | CEF childminder frozen meals pilot |

| 5 | Food and nutrition: Knowledge and skills for early years providers | Child feeding guide training |

| 6 | Food and nutrition: Community of Practice | Community of practice |

| 7 | Healthy eating consistent messaging | Food 4 Life programme |

The team took a cross-council approach, including not only the public health and early years teams, but also school caterers, children's centres, childcare providers, and local parents. They adopted a test and learn approach, iterating their initiatives as and when they experienced barriers. One of their four objectives was to improve the quality of food in early years, and this short case study focuses on two standout examples.

Childminder frozen meals pilots – meals on wheels

Councils informed us that they had little understanding of the food offered by childminders. Childminders experience multiple barriers to good nutrition, such as insufficient kitchen space, meeting the nutritional needs of various age groups and the ongoing cost-of-living crisis.

Nottinghamshire created an innovative pilot programme to provide ready meals to childminders. The pilot’s objectives were to test and determine if this might contribute to better nutritional outcomes. The Childminder Hot Meals Pilot made use of the council’s existing meals on wheels service to provide healthy, ready-made meals to childminders. They received a nutritious main course and a dessert for each child, supplied frozen and in bulk appropriate to their storage capacity. The pilot was positively received by childminders:

The lack of pots and utensils was great. I served the meal from the tray it was cooked in into a bowl for them to eat from. It’s a lot less than I’d normally have to wash up and it has given me even more time with the children … My time is precious, an extra activity a day where I’d usually be in the kitchen really benefits the children.”

Nottinghamshire was able to explore the barriers to their test and learn approach:

- The challenge of meeting the nutritional needs of nought - fives with food normally prepared for meals on wheels service.

- The cheapness of supermarket ready meals versus the home-cooked alternative.

- Ensuring sufficient variety and rotation of meals.

They are currently reviewing the programme to consider a second pilot and making use of the feedback from childminders and suppliers.

Food for Life in Nottinghamshire nurseries

Between 2020 and 2022 Nottinghamshire funded the Soil Association’s Food for Life (FFL) programme in seven early year settings with the aim of increasing the nutritional knowledge of early year practitioners and improving the nutritional profile of the food served. The FFL team ran a wide selection of initiatives: webinars on edible growing, menu planning and creative cooking, training modules, and 1:1 engagement. The pilot had some excellent results: five out of seven of the nurseries showed an improvement in knowledge, skills, and confidence, and the scheme improved the nutritional profile of meals. The nurseries were engaged and enthusiastic about the process but did raise the excessive cost of ingredients as a potential barrier:

Before starting this, we had never heard of the voluntary food and drinks guidelines. Now every menu change is checked against them by both of us [manager and cook].”

We didn’t know what was in the food we were serving before. We knew the name of it, but the ingredients were a mystery. Now we know exactly what’s in there and why it’s been included. We talk to every parent about our food offer now.”

Finally, two of the FFL accredited nurseries took part in the Community Food Hub project, increasing access to and affordability of good nutritious food by growing and producing food within their settings.

Conditions for success for early years nutrition in settings

The early years are a key stage in a child’s life, and good quality, healthy food offers the opportunity to create long-term healthy eating habits and contribute to growth and development. School food standards have shown that mandatory guidance and strong political buy-in within councils can positively impact children’s health and well-being. It is now time to bring more rigour and focus on early years nutrition and create the right conditions for success. Bremner & Co recommended that the LGA use their strategic position to ask that:

Government

- Review the voluntary guidance, EBSB, to ensure that it is fit for the purpose. This should be done alongside the sector to ensure that the guidance is useful for feeding children in early years settings (with some having limited staff and facilities), culturally appropriate, and affordable within current funding restraints.

- Reverse cuts to the Public Health grant. An increased focus on prevention through an uplift to the public health grant is needed, as well as a wider review of the adequacy of public health funding.

- Ensure councils are funded to support adequate early years resourcing. Teams need to be empowered to work with all settings to improve nutrition and not be limited to pure safeguarding or accounting for maintained settings only

- Adequately fund early years settings.

- In addition, appropriate monitoring and accountability mechanisms, or at least a review of how often nutritional outcomes are monitored by Ofsted.

- Roll out Family Hubs across the UK to ensure consistency and an equitable approach. This recognises the potential of Family Hubs to assist in delivering better nutritional outcomes for early years through parental support, engagement with health visitors and support for settings.

Councils

- Bring in strategic leadership and promotion of early years nutrition, looking for opportunities to align with other stakeholders such as Integrated Care Boards and Partnerships. Look for ways to make early years nutrition a political priority.

- Undertake reviews of their early years offer and assign equal priority to early years nutrition as they do to school food.

- Whilst it is recognised that councils are operating with constrained resources and funding, raising early years up the political agenda and considering settings in the 0-5 pathway has the potential to make considerable difference to nutritional outcomes.

- Seek out data that would help build a robust profile of child health – nutrition in settings and aligning the 2 – 2.5 early years setting checks with health and development checks for example.

- Review the benefits of matrix working in the early years, bringing in expertise from children’s centres and Family Hubs, public health, school teams, catering teams, settings and parents to give a rounded view on how to improve nutritional outcomes.

- Engage with settings on what resources would be useful. Consider awards schemes such as Food for Life or funding training for settings chefs or cooks such as LEYF’s Chef’s Academy

- Consider all settings within early years nutrition workstreams, where funding allows.

A recent report by the Royal Foundation Centre for Childhood showed that 91 per cent of adults agreed that early childhood is an important stage in shaping a person's future life, with 70 per cent agreeing that it should be a greater priority for society. Our report shows how the government’s funding of the sector affects the quality of nutritional care in settings.

The LGA also recognises the work that councils do working with parents and trying to improve the home food environment. Settings is just one part of the nought to five pathway. Stretched public health funding for councils also means that the early years often struggles to gain prominence on the child health agenda. Finally, without data and effective monitoring policies, we do not know what children in their early years are eating, and if we want to set them up for a better chance in life and turn the dial on obesity rates, we really should.

Useful resources

- Beyond Boundaries - London Councils report on early years integration

- Beyond Boundaries self-evaluation tool

- London Early Years Foundation research on early years settings

- Obesity Health Alliance - Turning the Tide report