Michael Kenny, Owen Garling and Steph Coulter from the Bennett Institute for Public Policy, Cambridge, share their thoughts on what the case for cultural infrastructure might look like.

Over the course of the last decade, there has been a substantial reduction in how much funding local government in England receives, with the National Audit Office estimating it was reduced by over 50 per cent in the decade between 2010/11 and 2020/21. Coupled with other shocks, such as the COVID pandemic and the cost-of-living crisis, more and more local authorities are reaching the point where their finances are becoming unsustainable, as evidenced by the increasing number of Section 114 notices being issued by crisis-ridden councils. The nature of the services that local government delivers, and in particular the mix of statutory services, such as social care, it is legally obliged to provide, alongside the non-statutory ones that local government has traditionally delivered, means that reductions in funding are not falling equally across services.

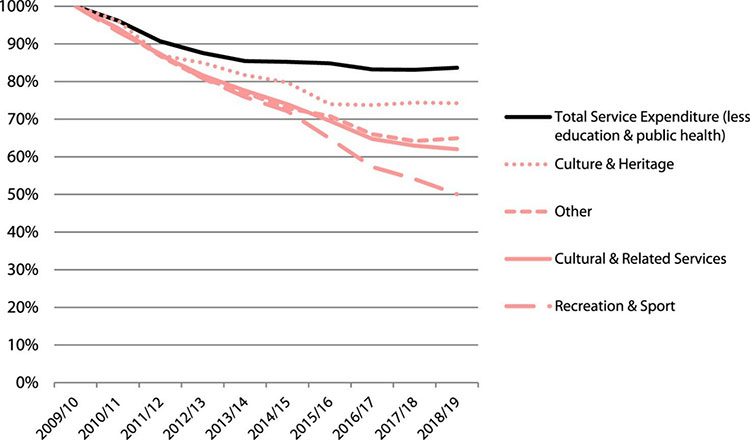

What does this mean for cultural provision and the arts in England, given that local government is still the largest funder in this area, providing over half of all public spend on arts in the year 2019/20? Announcement of cuts in funding for arts and culture have been made by many local authorities, with perhaps the most extreme examples being Suffolk County Council and Nottingham City Council’s recent declarations that they will be ending the funding of cultural services entirely. This chart, taken from Rex and Campbell’s study of the impact of austerity measures on English local government funding for culture, shows a steep reduction in available funding between 2009-10 and 2018-19.

Diagram 1

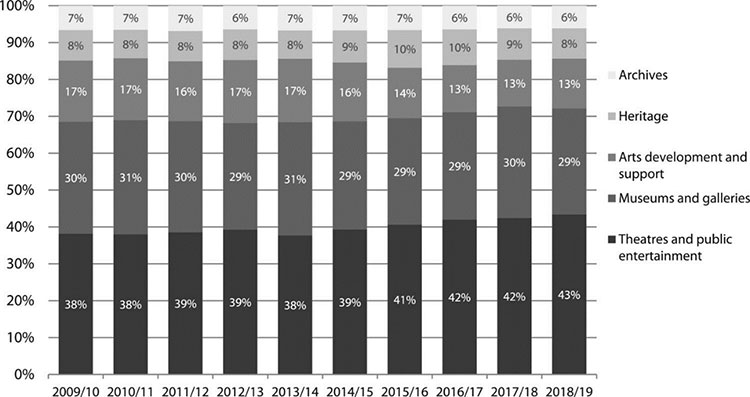

Within the broader category of cultural provision, these funding cuts do not fall uniformly. Rex and Campbell identified that funding under the heading of ‘arts development and support’ – which is typically used to support ‘softer’ and more informal grassroots activities -- has been particularly vulnerable to funding reductions compared to other areas of expenditure, such as museums, galleries, theatres and public entertainment.

Diagram 2

This slow-burning crisis of local cultural provision is rather ironic given the government’s assertion, set out in the Levelling Up White Paper, of the integral importance of “pride in place” to the social and economic fortunes of poorer communities. This represents an overdue recognition that the value and impact of culture, heritage and sport are not purely economic in character, and acknowledges the role that artistic and sporting activities play in shaping peoples’ sense of well-being and local attachment.

This recognition has also underpinned the development of a number of ambitious cultural plans by some of England’s combined authorities, and the notable profile given to the cultural industries in the regeneration plans advanced by, for instance, the emerging North East Combined Authority in England.

The commitment to taking a more strategic approach to the ‘assets’ that undergird the affective, cultural life of places sits awkwardly alongside deep retrenchment at the local level. This sentiment was recently expressed by Andy Haldane, Chair of the government’s Levelling Up Advisory Council, who has lamented the consequences of underinvestment in social and cultural spaces.

One way in which this dissonance might be addressed, we suggest, would be for policy-makers – at national, devolved and local levels – to start thinking in more rigorous and systematic ways about the kinds of value created by the spaces, opportunities and activities that promote cultural and artistic activity and exchange in places. The concept of ‘cultural infrastructure’ is a particularly helpful one in this regard. The idea of mapping and understanding local cultural infrastructure has been pursued by several different local and devolved bodies, including the West Midlands Combined Authority, the Greater London Authority, and local councils such as Milton Keynes. Further afield, cultural infrastructure plans have also been developed in cities such as Sydney, Vancouver and Amsterdam.

But what exactly does it mean to think about something as multi-faceted and amorphous as culture through the lens of ‘infrastructure’?

In our own work on this issue – which is supported by the British Academy – we are exploring what it means to consider cultural (and social) assets, both public and private, as infrastructure. The main implication of this idea is that we start to see a rich and diverse set of cultural assets both in terms of their instrumental benefits to the prosperity and cohesion of communities, and the platform they provide, along with other kinds of infrastructure, for a healthy and functioning community.

Equally, if we think of cultural and heritage buildings, amenities and spaces as pieces of essential local infrastructure, then we may well be drawn to think differently about the current funding model. Just as we would not expect local areas to have to bid to central government or arms-length bodies to win funding for a new reservoir or electrical grid maintenance, we should not expect local cultural development to be subject to time-consuming and expensive bidding processes, or supported by pots of funding that are typically designed around the priority of economic growth. And, given the significant geographical discrepancies that characterise the allocation of cultural funding at the national level, including both National Lottery and Arts Council England allocations, a focus upon cultural infrastructure also brings to the fore long-standing inequalities across different parts of the UK, and the persistent, ingrained bias towards funding the welter of artistic endeavours and cultural institutions that are located in London in particular. Indeed, it may well be helpful to conceptualise culture as part of a wider suite of Universal Basic Infrastructure (alongside healthcare, policing and educational services) to which every community should be entitled.

Further, an infrastructural approach necessitates a consideration not just of sites of cultural consumption, such as cinemas, football stadiums or museums, but also the places where culture is created. Many of the cultural strategies developed by local authorities, such as London’s Cultural Infrastructure Plan, focus upon where production happens, with maps showing the locations of artists’ studios, training/educational facilities, and affordable housing for cultural professionals. These are typically used to support the case for affordable and accessible spaces for artistic and related commercial activity.

The cultural infrastructure lens might also lead us to think about non-tangible infrastructure, such as digital connectivity, as part of the stock of assets that contribute to cultural vitality in places. Using this lens might also provide a helpful framework through which to weigh up the inevitable dilemmas arising from dwindling resources, and the challenges associated with the rising costs of heritage buildings and facilities that are increasingly expensive to maintain. By shaping a focus upon the local cultural ecosphere – rather than merely weighing the future costs of maintaining individual assets – decision-makers may be able to establish clearer priorities about which activities and amenity are particularly valuable, perhaps because they are more widely and diversely used, or because they are helpfully muti-purpose in kind (such as cafes that may be used by artistic freelancers to produce work). And such a framework will be invaluable in the face of the very hard decisions that lie ahead in the context of dwindling resources.

Taking an infrastructural approach also helps us to connect the foundational role that culture plays in the UK’s vibrant creative industries. It is striking to note that the total investment by local government in arts, culture, tourism and heritage of over £1 billion is less than one per cent of the £103.8 billion of Gross Value Added generated by the UK’s Creative Industries in 2020. Many of today’s successful contributors to the UK economy – such as the music industry – started off as beneficiaries of investments in grassroots infrastructure. Powerful arguments for protecting local cultural spaces – such as live music venues – because they function as seedbeds for the creativity that flows into the music industry are currently being advanced; for instance by the Music Venue Trust, which is calling for a £1 contribution towards grassroots venues from every arena and stadium ticket sold.

Finally, adopting this lens should enable a better appreciation of the inter-dependent nature of local assets. Transport, for instance, can be a barrier to those looking to reach cultural spaces, and so an understanding of the complementary investments that may need to be made to enable the broadest possible use of such amenities is especially important.

In 2016 UK government published a Culture White Paper setting out a grand vision for the cultural sector. Subsequently, the Levelling Up White Paper set out the importance of culture, heritage and sport for contributing to, or restoring, feelings of pride in local places. Adopting the framework of cultural infrastructure would represent a further step-change by a future UK government, we would suggest, towards recognising the value created by the arts and cultural provision in policy terms. It would help decision-makers appreciate the intrinsic importance of artistic endeavours and cultural consumption to the life and well-being of communities throughout the UK. And it would enable local and national leaders to articulate better what many intuitively understand: that culture, sport, heritage and the arts are not luxury items, or mere supplements to the services and amenities that people rely on in their daily lives. They are, in fact, integral parts of the social plumbing that makes communities prosper, democracies flourish and individuals live more fulfilling and healthy lives.

Michael Kenny, Director

Owen Garling, Knowledge Transfer Facilitator

Steph Coulter, Research Assistant