This case study forms part of the publication, Bespoke support for people with learning disabilities and autistic people, an evaluation on the impact consequence for local authorities and councils of delivering bespoke support to autistic people and people with a learning disability, including people who have been detained under the Mental Health Act (or at risk of being detained).

Danny was in Calderstones hospital. Danny was brought to the provider’s attention via a conversation between the commissioner and the CEO of My Life. They had worked together previously, and the referral for supporting Danny came via a trusted relationship with the commissioner. My Life were invited to join a Teams meeting with lots of professionals to discuss discharge planning for Danny.

Danny was receiving joint funding from both health and social care.

A house was purchased for Danny via an NHSE Transforming Care grant, and a housing provider took on the management of the tenancy. Danny’s family were involved in helping to identify a suitable property.

The transition process to prepare Danny for moving out of hospital had to take place during the COVID-19 pandemic. The provider, the social worker and the community nurse who had been identified to support his discharge had never met him. To build a relationship, the registered manager at ‘My Life’ started ringing the ward. She spoke to different staff on the ward to start gathering information through short conversations.

Eventually, the registered manager was able to speak to Danny. Their conversations were focused around Danny’s interests initially, so they talked about Only Fools and Horses and old TV comedy programmes to build a relationship. The manager also linked up with Danny’s parents who provided lots of additional information. A really positive relationship developed between Danny’s parents and ‘My Life’ staff. Danny’s parents were very involved and very supportive.

A move date was planned and transition commenced, with Danny visiting the provider’s main site where they had animal therapy, a respite chalet and lots of staff and onsite activities available. The plan was to support Danny to build a relationship with the new provider’s staff and also for him to become comfortable spending time outside of the hospital environment.

There were animals on site, which was a positive thing for Danny as he loves animals. He spent time and ate lunch in the respite chalet on site. Danny’s transition went on for a few weeks. He went home to Mum and Dad’s house with transitional support and a gradual process took place to integrate new staff into Danny’s new home. Danny started riding horses and doing things he hadn’t done for years. Although the provider had been warned there was a risk of Danny absconding, he didn’t make any attempts to abscond during his transition visits. At the end of the transition process, Danny moved into his own home full time.

The provider had received lots of paperwork from Danny’s past. It was really negative, and portrayed Danny as very high risk.

The manager rang the safeguarding lead for their organisation and they spent time going through all of the paperwork together.

Danny had never actually been convicted of anything, but there was a very risk-averse approach to supporting him which was very restrictive.

The provider went through the risk assessments and spent time talking to Danny’s parents. There was a collective understanding that Danny’s risks outside of a hospital setting were unknown as it was a new scenario for Danny. The risk assessments were re-written as he came out of hospital and were updated weekly as staff observed and got to know Danny.

Within his housing specification, there was a recommendation to place a seven foot fence around Danny’s house to prevent him climbing and ‘absconding’. Danny lifted it up and was able to get underneath it! (Nobody anticipated that!)

Danny’s staff are very experienced, and they are paid a higher rate to reflect their skill set, and the level of risk they are required to manage. There are a number of restrictions around Danny due to behavioural risks. Danny has a Community DoLS in place for his own safety; he does not go out unescorted. Danny is joint-funded by health and social care and has a Personal Health Budget managed by a third-party budget holder organisation (similar to an ISF arrangement).

The provider developed a support plan around Danny’s assessed needs and outcomes, which was approved. Danny receives 2:1 support during day, and 1:1 waking support at night. Danny’s hours can be used flexibly or banked when needed to plan for times when he may need more or higher levels of support. This also provides some contingency for additional staffing to be drawn upon if Danny leaves his home unescorted.

A training budget was also built into Danny’s plan and budget, which can be drawn down by the provider.

Danny still occasionally attempts to leave home without support, so the risk around this and the contingency for additional support is needed as a back-up. Having this flexibility within the funding and staffing arrangements enables the provider to be responsive and to manage risks without an escalation which could lead to a re-admission to hospital.

The learning disability nurse is now planning to discharge Danny because he is doing so well. The local community health teams have provided good support via trauma training and the speech and language team for Danny’s swallowing and eating difficulties. The special support team were on hand for help/advice/support in relation to Danny’s behavioural risks.

Danny’s support team were employed specifically for Danny, and the provider also has a peripatetic staff team who are trained to work with Danny and are able to step in at short notice. This means that Danny does not have anyone supporting him who he does not know.

Danny now has his own car, which his staff drive and he has just had his first holiday in over 10 years, a week in Wales.

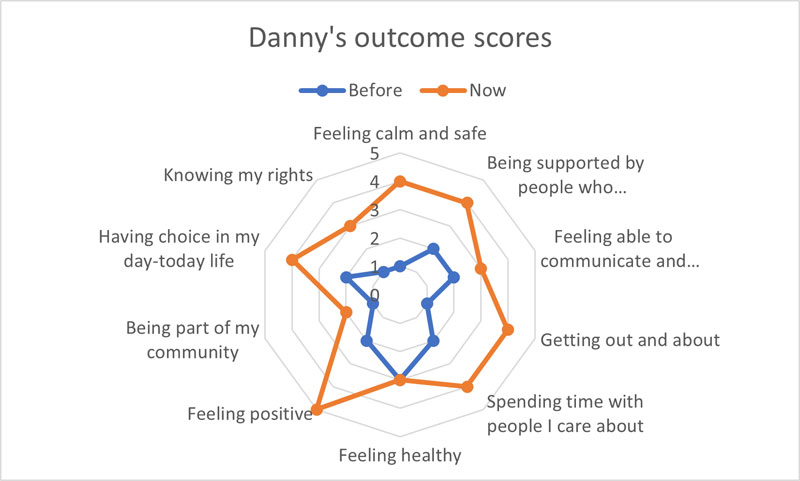

‘My Life’ uses the POET (Personal Outcomes Evaluation Tool) tool as a way of measuring the person’s experience at the start of the process and then at later review points, as a way of tracking progress towards outcomes.

‘My Life’ is waiting the outcome of their first CQC inspection.

feeling calm and safe 1 before and 4 now.

being supported by people who understand me well 2 before and 4 now.

feeling able to communicate and being listened to 2 before and 3 now.

getting out and about 1 before and 4 now.

spending time with people I care about 2 before and 4 now.

feeling healthy 3 before and 3 now.

feeling positive 2 before and 5 now .

being part of my community 1 before and 2 now.

having choice in my day-to-day life 2 before and 4 now.

knowing my rights 1 before and 3 now.