Swindon combined a case formulation approach with a focus on identity and its link to offending, to promote interventions with young people which moved away from ‘managing risk’ to supporting them to develop a pro-social identity which naturally shifted them away from risk and offending behaviour.

The challenge

Swindon Youth Justice Services (YJS) found that traditional approaches to offending which defined children by their past experiences and current levels of risk, were leading to intervention plans which were focussed on addressing risk in a child’s behaviour and did not take into account the importance of identity and its impact on offending.

As an example, a child (N) was heavily involved with an organised crime group where he was being exploited to be involved in activity such as drug dealing and associated serious violence. His older cousin was stabbed with life changing injuries and he was himself judged to be at imminent risk of harm. He was also classified as ‘MAPPA Category 3’, a categorisation which labelled him as a dangerous offender who ‘is capable of causing serious harm and requires multi-agency management’.

N had experienced a lifetime of trauma, neglect, abuse and loss. This continued through his school years with exclusions, punishment and rejection.

The solution

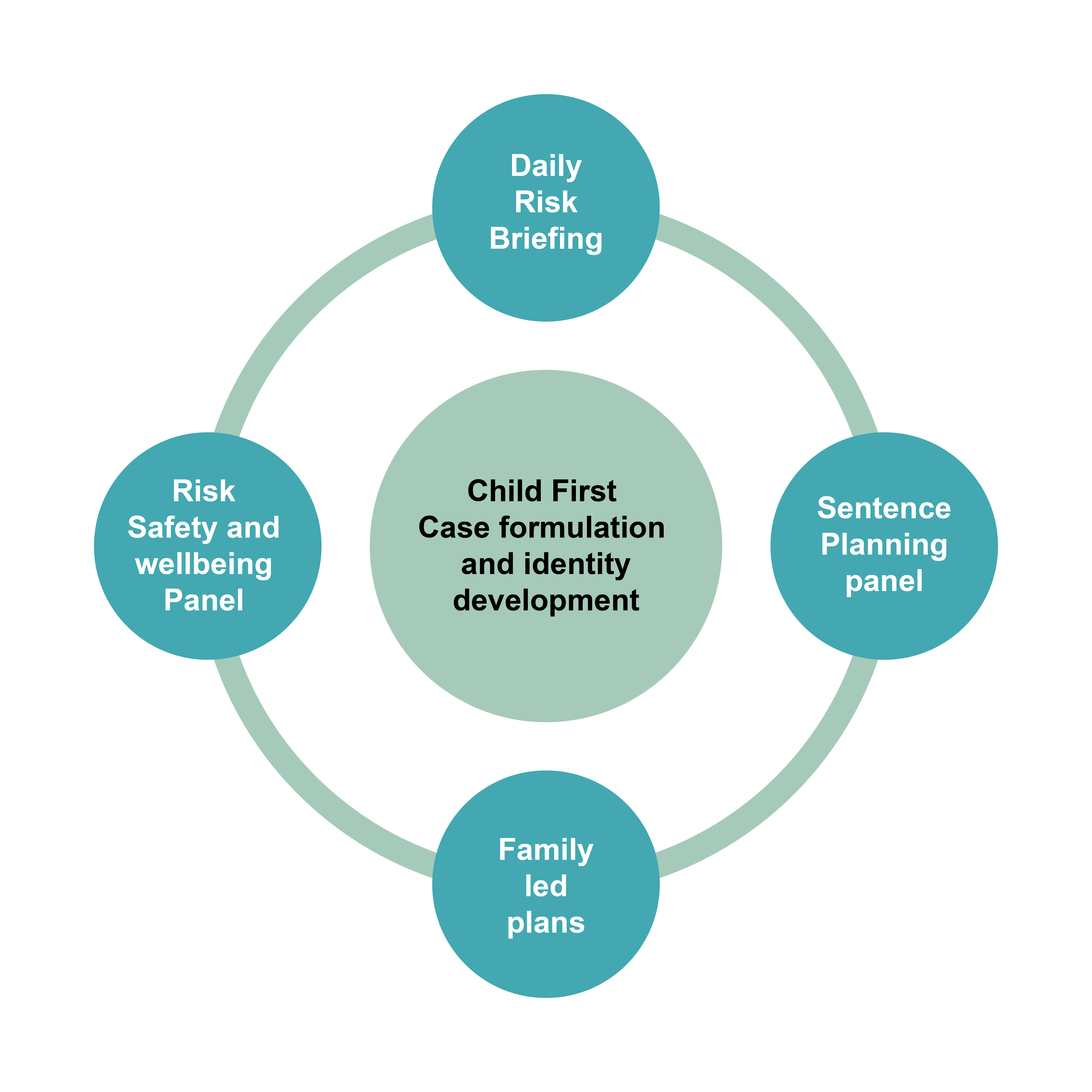

Swindon now uses a case formulation model with the assistance of Forensic Child and Adolescent Mental Health Service to ask ‘what has happened to N’ rather than ‘what is wrong with N.’ Figure one shows the case formulation model for 'N', with Child First at the centre of the diagram, with the planning and teams around them needed to support.. Around the outside of the middle circle is

The team now spends much of the assessment period thinking through the case formulation model rather than the traditional ‘offence analysis’ approach. Through this case formulation, they focus on using an ‘identity lens’ to understand the child’s current behaviour, prioritising the view that behaviour stems from a child’s identity and the way in which they perceive themselves, their relationship to others and the world around them. Interventions then seek to work on identity development to take them from a ‘pro-criminal’ to a ‘pro-social’ identity.

Figure one: Case formulation model for 'N' and the interventions needed to work with the child

Understanding N’s identity through the lens of his past experiences

Unpicking what elements of his identity promoted N to offend was the first step in the team’s approach. These included his familial history and academic history. The team involved in the case formulation identified that N’s history of trauma, abuse and familial imprisonment had a direct impact on his sense of self, his attachment style and his self esteem. This had caused him to have an identity that perceived the world around him to be unsafe and dangerous and himself to be part of this, being unlovable, uncontainable and not worthy of trusting, nurturing relationships, value, achievement or love.

These experiences during his childhood and early development fundamentally shaped his identity and a ‘wiring’ of his brain to hypervigilance and fight, fright, freeze responses, making him vulnerable to grooming and having a propensity to violence as a result. The criminal activities that N was involved with reinforced this identity, as did his interactions, which were either with adults and children similarly involved in the criminal justice system or with professionals who ‘supported’ him from a deficit perspective. This did not provide any opportunity for an identity shift.

Intervening to shift identity through the ‘5Cs’

The team then moved to think about N’s strengths, interests and goals. These included; wanting to make money, wanting a job, not wanting to be defined by his family's criminal behaviour, being funny, being kind, being able to help and not being seen as a risk in all contexts. They worked with N to discuss what would help him achieve his goals and therefore support the development of a pro-social identity.

The team used the ‘5Cs’ of support as taken from the identity development framework to plan and complete work with N:

The focus of work with N was supporting the development of his identity, taking him from a ‘pro-criminal’ identity to a ‘pro-social’ identity. It was decided that all interventions would be designed and delivered to meet this aim. Work was therefore future-focussed with a priority to provide N with opportunities that would support identity shift.

Examples of this include small interactions such as when N expressed an interest in mechanics. That afternoon, the allocated worker supported N to look at her car engine, learn where the key parts of the engine were and check the oil in the car. These types of interactions started to build the trust between N and his allocated worker, and began the journey towards him considering new knowledge and experiences as trustworthy and relevant to his life.

The team also provided future-focussed interventions that supported a sense of achievement, for example supporting N in achieving his Construction Skills Certification Scheme card and getting an apprenticeship.

The allocated worker always focussed work with N on his motivations and strengths and work was always completed in partnership, with human relationships and interactions that promoted value and worth at its core.

Interventions delivered were unique to N and ensured a focus on how he perceived himself and the world around him. For example, N called his worker to say he knew that he would fail a test and therefore couldn’t take it. His worker supported N to understand that he could only try his best and that he could feel safe in failure as a process towards success, rather than it defining his identity and his future. This was the opposite of his previous experiences of failure. It gave him confidence that failure would not reinforce his lived experiences, but allow others to tell him he was brave, courageous and destined for success through effort and resilience.

Approaches with N were consistent and frequently focused on remembering things that were important to him. For example, remembering and talking about something he mentioned in previous sessions, focusing consistently on what was important to him, and maintaining consistency with planned session times and days. Importantly, this also involved remaining involved when things were difficult and supporting N not to lose a focus on the future and his future self when risk increased.

The whole professional network discussed the model and approach including how it related to social work and youth work theories. All professionals around N were supported to understand how they could use their interactions with him to repair his experiences of attachment and support N to feel a sense of value and worth. Consistent pro-social and future focused activities and interactions across the professional network were a key element to a successful outcome for N.

The impact

Using a case formulation and approaching N’s behaviour as an element of his current (and changeable) identity helped the team in Swindon to hypothesise what support N would need to shift from a pro-criminal to a pro-social identity. It also helped them to focus on consistently providing exposure to activities and interactions that enabled him to begin to experience and feel different about how he perceived himself and the world around him and what roles would eventually help him move away from offending for good.

N desired reputation and belonging and the team’s focus on this need for identity gave this to him via strengths and future focused activities and interactions.

N is no longer coming to the attention of services. He was originally considered for MAPPA Category 3 and is now not open to specialist services. N is continuing to seek employment and is being considered for a role within the Youth Justice Service peer advocate programme where he can continue to facilitate change within the service.

More widely, Swindon’s focus on shifting young people’s perceptions of themselves through identity work has seen their custody rates per 1000 children drop from 0.42 to 0.00 for the first time ever (April 2023).

How the approach being sustained

Staff in Swindon continue to take a ‘child first’ approach, where they spend time getting to know the individual child and not the child portrayed by services around them, which is often based around notions of ‘risk’ and ‘danger’.

Time is taken to gain trust and build a working relationship with the child that then sets the foundations for an intervention that seeks to help children to move forward into positive, pro-social futures for themselves.

They are also focussing on meaningful participation that supports young people’s identity shift, whereby the process of participation itself is as important as the outcome, this includes currently having two paid employees who are young people that have been supported by the service.

Lessons learned

A lot of work needs to be dedicated to undoing the normal deficits and risk-based approaches of professionals which may have fed into young people’s negative identity and therefore exacerbated offending. The environment of the intervention and the interactions that take place within it are also crucial, Swindon have completely redesigned their offices having taken both young people and staff on a ‘walk through’ of the service to identify where the environment contributed to deficit-based identity (i.e. signs and posters warning about behaviour and rooms that felt like children were being interviewed) and make changes. They have also focussed on ensuring that every interaction a child has contributes to their sense of worth, for example staff knowing all children’s names, remembering what they like to drink and asking them about something they know is happening in their life, regardless of whether they are their allocated worker or not.

The importance of a focus on the future in contributing to identity shift cannot be underestimated. This also means spending very little time focussing on managing risk, which can feel counterintuitive and unsettling when the risks to a child are deemed to be high. To aid this, it can be helpful to understand that ‘risk’ is only high in specific circumstances which are defined by an identity which the intervention seeks to shift.

Contact

References