Foreword

Social prescribing is not a new invention. For decades community navigators and wellbeing advisers in local government have used social prescribing to help tackle loneliness, improve mental health and more.

As conveners of place and local leaders who know their communities and the voluntary and community sector, councils have always sat at the heart of social prescribing. Through our role as social care and public health commissioners, we work with some of the most vulnerable residents and have a firm commitment to the health and wellbeing of our communities. We deliver a wide range of services which social prescribing link workers can refer people to - from parks and playing fields, to libraries, leisure centres, art galleries and museums.

Thinking creatively, investing in what already exists and joining up services will become increasingly important as we recover from the COVID-19 pandemic and the cost of living crisis increases the need for housing, debt advice and growing demand for mental health, social care and health services.

The pandemic has only served to highlight how crucial culture, leisure, parks and creativity is to people’s lives. Many culture and leisure organisations responded with remarkable speed to the pandemic, adapting their services to deliver digital activity, wellbeing boxes and providing direct support to the most vulnerable. Harnessing innovation and the wealth of culture and leisure related social prescribing initiatives already being run will be crucial to meet the challenges facing communities and councils. I am proud to share some examples of these in this handbook. The case studies are a mix of examples identified prior to and during COVID-19, all remain relevant for the sector as we move into recovery.

Councillor Gerald Vernon-Jackson CBE

Chair of the Local Government Association Culture, Tourism and Sport Board

About this handbook

This handbook highlights the vital contribution culture, leisure, green spaces, and sport make to social prescribing. It shares inspiring case studies from across the country of councils using a range of innovative in person and digital models to deliver social prescribing initiatives to improve the health, wellbeing and care of individuals. The handbook explores the opportunities for councils and their partners to work together to expand the reach of their social prescribing offer, level up growing health inequalities, support communities affected by the rising cost of living and tackle the burden on social care and NHS services. The handbook builds on the LGA’s publication Just what the doctor ordered, social prescribing – a guide for local authorities.

Introduction

Rt Hon. Lord Howarth of Newport, Co-Chair, All-Party Parliamentary Group on Arts, Health and Wellbeing declared “the time has come to recognise the powerful contribution the arts can make to our health and wellbeing”, in the Creative Health short report.

During the COVID-19 pandemic we witnessed first-hand how key community assets such as libraries, theatres and leisure centres responded rapidly to the needs of their communities. Alongside this local parks and open spaces provided solace to many.

Repeated lockdowns and social distancing saw the nation turn to home-based arts, fitness and cultural activities, with around 1 in 5 people increasing their arts activity engagement and 1 in 8 increasing how much they watched arts performances online, above usual pre-pandemic levels. Many culture and leisure organisations responded by providing digital activity such as online book groups, children’s activities, exercise classes and streamed theatre performances. The reach of digital output during the pandemic was exceptional. Libraries Connected reported a 600 per cent increase in digital membership as well as a fourfold increase in the number of eBooks borrowed and Kingston Library Service reached on average 10,000 people for each of its online Rhyme Time sessions.

The pandemic fast tracked relationships in many areas, as councils, health, voluntary and community sector partners and community leaders worked together at speed to respond to the needs of their communities, especially for the most vulnerable and shielding residents. This included but was by no means limited to socially distanced deliveries of care packages, medical prescriptions and arts and crafts activities. As well as making phone calls to residents who were lonely or isolated and getting key public health messages and support out to communities via community leaders, where their reach was greater than the councils’. Norwich and Norfolk Festival Bridge were one of many arts organisations throughout the country who delivered creative packs to over 7,500 families, enabling children to access the benefits of creativity while away from school.

As we emerge from the pandemic and our communities face new challenges with the cost of living crisis, these relationships are more important than ever as we look to reduce health disparities amongst communities. This handbook will demonstrate how utilising sport and culture in social prescribing can make a powerful contribution towards improving and empowering the lives of individuals and can reap many wider benefits and will hopefully give you a blueprint for developing services in your area.

Putting it into practice

What does good social prescribing look like?

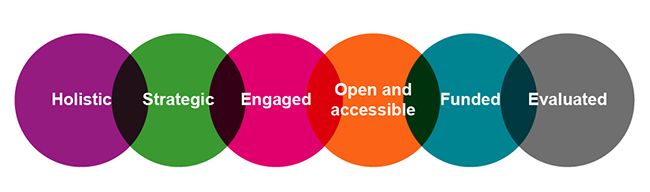

Social prescribing is most effective when internal and external senior stakeholders (both at political and at officer level) are committed and there are strong partnerships for delivery. Strong social prescribing initiatives often share the qualities highlighted in figure 2.

Figure 2

- Holistic and co-ordinated: works seamlessly across a range of services from GPs to libraries, to offer a holistic approach to health and wellbeing that is about more than clinical needs. Link workers are embedded in communities and the Voluntary, Community, Faith, Social Enterprise sector (VCFSE) connect people to these groups and services. Link workers build trust among the individual being referred and the service provider, ensuring they are a right fit.

- Strategic: identify strategic and commissioning opportunities to advocate for social prescribing. Quality standards are co-developed and agreed with strategic and delivery partners to achieve the best outcomes.

- Engaged and empowering: involves, collaborates and co-produced with local communities.

- Open and accessible: services used for social prescribing should be open to the public, not prescription-only, available to all ages from young to old and deliver the responsibilities under the Equalities Act 2010. Services are accessible, including supporting reasonable adjustments and offer activities in a range of models such as in person, hybrid and online, and avoid digital exclusion.

- Funded: social prescribing schemes have a sustainable funding model. Costs attached to using community services, such as libraries, arts and culture services and venues are taken into consideration. Individuals delivering social prescribing services are appropriately trained and equipped to meet the needs of people accessing services.

- Evaluated: evaluation and monitoring mechanisms are implemented into the design of programmes in order to refine the programme, improve outcomes for individuals and make the case for future funding.

There are a range of social prescribing models to consider. This could be a hub model where people are referred into a central point for information and support, or one where link workers operate individually across different community areas.

Making the case for investment

A statement from Shropshire Council evaluation of social prescribing (2017-18) declares “the initial appointment with the social prescribing advisor has changed my life. I am now fitter and have lost two stone in weight. I feel more energetic and healthier”.

Social prescribing, the arts, culture, sports, leisure and parks services all make a significant contribution to addressing a wide range of local and national policy priorities. Studies point to improvements in quality of life and emotional wellbeing, mental and general wellbeing, improvement in levels of depression and anxiety and job prospects. Some of the policy areas they can make a direct impact on include:

- levelling up: improving health and wellbeing, narrowing the gap in healthy life expectancy, strengthening communities through investment in activities that enhance physical, cultural and community led projects.

- public health issues such as tackling obesity, reducing health inequalities, improving mental wellbeing and supporting people with long term conditions

- delivering the NHS’ personalised care agenda and reducing the demand on health and social care services, tackling long waiting lists, supporting people with long COVID.

Social prescribing remains high on the government and NHS’ agenda. The Government’s Levelling Up the United Kingdom White Paper makes reference to social prescribing. Specifically, it supports the ambition to narrow the gap in Healthy Life Expectancy (HLE) by 2030 and increase HLE by five years by 2035. (Levelling Up Mission 7).

The evidence of the benefits extends beyond health services to social care, skills and employment and public health to name but a few. This data can be incredibly helpful especially when engaging with NHS commissioners where there may be differences in organisational culture, priorities and language which can act as a barrier to securing investment and joint working. It can also help to open up wider conversations with public health and social care commissioners. For example, recent UK evaluations have reported the following benefits to the health sector:

- Sixty per cent reduction in GP contact times in the 12 months following intervention compared to the previous 12 months

- Twenty-five per cent reduction in A&E attendance in the social prescribing group, with a 66 per cent increase in A&E attendance by the control group

- Seventeen per cent reduction in A&E attendance and seven per cent reduction in non-elective in patient stays were reported in the 12 months post intervention compared to the 12 months before it from the most recent evaluation report from the Rotherham Social Prescribing Service.

The benefits to primary care also include increased capacity because people with non-clinical needs are supported by link workers and community activities. For example, in the Alvanley Family Practice, patient numbers at the practice have gone up by 26 per cent in the last two years but the pressure on staff has gone down as a result of its Health Champions approach (see case study). GPs now see 12 patients per session and not 15. Leaving them more clinical time for patients.

While recent evaluation undertaken by Sheffield Hallam University (September 2020) found that 81 per cent of service users experienced positive change on at least one outcome measure ranging from improved wellbeing to skills development which could potentially lead to employment and/or improved job prospect. It showed that of the control group participating in social prescribing:

- Forty-seven per cent of people felt more positive

- Forty-six per cent of people made progress on work, volunteering and other activities

- Thirty per cent of people made progress on money.

Social prescribing can also provide a decent return on investment and social return as demonstrated by the Red Cross’ analysis to identify the economic impact of the connecting communities service. It found a social return of £2.04 per £1 invested (based on running costs with set up costs removed). If set up costs and co-ordination costs are included the return was £1.48 but the analysis was confident this will increase to £1.95 in future. The joint NHS England, Public Health England and London Mayor’s Office report Social prescribing: Steps towards implementing self-care – a focus on social prescribing cites the Bristol Wellspring project which estimated a social return of £2.90 in year for each £1.00 invested.

However, social value is not just about monetary worth or savings but also about the value that people place on the changes they experience in their lives. Where Social Return on Investment (SROI) is reported, it is usually greater than simple financial savings. A systemised review of social prescribing schemes by Helen J. Chatterjee et al (June 2017) reported the following multiple benefits:

- increases in self-esteem and confidence, sense of control and empowerment

- improvements in psychological or mental well-being, and positive mood

- reduction in anxiety and/or depression, and negative mood

- improvements in physical health and lifestyle

- reduction in visits to general practitioners, referring health professionals and primary or secondary care services

- provision to general practitioners of a range of options to complement medical care for a more holistic approach

- increases in sociability, communication skills and social connections

- reduction in social isolation and loneliness, support for hard-to-reach people

- improvements in motivation and meaning in life providing hope and optimism acquisition of learning, new interests and skills.

Tips for success

1. How can social prescribing deliver on local priorities? Take the time to identify how social prescribing relates to local NHS and council priorities and how it can add benefit. This will help to make a persuasive argument for investment and partnership working across different service areas both within and external to the council.

2. What evidence and data supports this offer? Build a strong and well evidenced business case demonstrating the positive impact on individuals and the potential savings that could be made to over-stretched budgets. Public health teams hold a wealth of data insights and may be able to support the process.

3. What local structures are in place and where is your influence strongest? This could be the local health and wellbeing board, the Integrated Care System, Integrated Care Board, the Primary Care Networks (PCNs), public health team. Who do you need to influence?

4. How can you make the shift from a delivery partner to a strategic partner? Get creative! The All-Party Parliamentary Group on Arts, Health and Wellbeing’s Creative Health report recommends appointing creative health champions to board or strategic positions to promote and encourage the use of the arts in health. Currently, 45 creative health champions are represented in trusts, councils and clinical commissioning groups.

Working with partners

Partnership working is key to building a rich local offer. Before embarking on your journey it is important to get a clear picture of:

- Who are your local partners?

- What are your communities’ needs?

- What are your local assets and where are they located?

- What resources are available?

- Which organisation is best placed to act as the primary social prescribing lead?

- What model of social prescribing would work?

In this section we look at some of the challenges affecting partners, this will help to identify where you might be able to add value.

Social prescribing link worker: link workers act as a bridge between new and established community organisations, and the formal health and care system. Arrangements will vary across the area, some maybe part of existing schemes, employed within Voluntary, Community Social Enterprise (VCSE) organisations or directly employed by the PCN. Recent research shows that some link workers who are new in post, or not employed within wider organisations have struggled to find a role within the wider community response in the absence of established links into the community. Many link workers are also seeing the increased numbers of referrals by as much as 700 per cent in some cases because of the pandemic.

Integrated Care Systems (ICSs): are new partnerships of organisations that come together to plan and deliver joined up health and care services, and to improve the lives of people who live and work in their area. ICSs are made up of the Integrated Care Board (ICB) and the Integrated Care Partnership (ICP). On 1 July 2022 under the Health and Social Care Act 2022 (April 2022) all 42 ICSs were put on a statutory footing and given responsibility for funding, performance and population health. Their purpose is to remove organisational barriers and encourage collaboration to tackle inequalities, enhance productivity, value for money and help the NHS support broader social and economic development. They are also tasked with tackling complex challenges such as improving the health of children and young people, supporting people to stay well and independent, acting sooner to help those with preventable conditions, supporting those with long-term conditions or mental health issues, caring for those with multiple needs as populations age and getting the best from collective resources so people get care as quickly as possible. The extent to which ICSs have developed varies across the country with some more established and with better partnership working in place then others, which may be a challenge for outside influencers. The term ‘ICS’ is also used to refer to the geographical area covered by the system. While strategic, at-scale planning is carried out at the ICS level, places will be the engine for delivery and reform at place and neighbourhood level. Each ICS covers a population size of 1-3 million and is not coterminous with council boundaries meaning more than one can fall into an ICS area.

Integrated Care Board (ICB): a statutory NHS organisation responsible for developing a plan for meeting the health needs of the population, managing the NHS budget and arranging for the provision of health services in the ICS area. They are accountable to NHS England for NHS spending and performance. ICBs have replaced clinical commissioning groups which have been abolished. ICBs are expected to work closely with all health and wellbeing boards in their area (those whose area coincides with or includes the whole or any part of the area of the ICB). Before the start of each financial year, each ICB and their partner must publish a five-year joint forward plan, setting out how they propose to exercise their function. These plans must describe any steps taken to implement relevant joint local health and wellbeing strategies. Each Health and Wellbeing Board (HWB) must be given a draft of the plan, or any revised plan, and be consulted on whether it takes proper account of each joint local health and wellbeing strategy.

Integrated Care Partnership (ICP): a statutory committee jointly formed between the NHS ICP and all upper-tier councils that fall within the ICS area. The ICP will bring together a broad alliance of partners concerned with improving the care, health and wellbeing of the population, with membership determined locally. The ICP is responsible for producing an integrated care strategy on how to meet the health and wellbeing needs of the population in the ICS area.

Primary Care Networks (PCN): PCNs bring together groupings of local GP practices with other primary and community care organisations to join up health and care services at neighbourhood level. Serving populations of around 30–50,000 patients, PCNs are the channel for social prescribing link worker resources and in many cases will host the link worker service. The role of PCNs is to help general practice by using economies of scale, overcome barriers between primary and community services, and develop population health approaches. Some are still in development, but more mature networks are now able to deliver more joined up care for patients by developing multidisciplinary teams and recruiting additional roles to ease workload pressures.

Children and adults social care and public health: falls under the responsibility of unitary and upper tier councils. Social prescribing schemes may already be run or funded by public health or social care and teams are likely to have developing or established relationships with ICSs, ICBs, PCNs, VCSE and link workers. Public health teams hold a wealth of population health insights and are responsible for developing the local Joint Strategic Needs Assessment (JSNA) and local Joint Health and Wellbeing Strategy (JHWS), which identify local needs and priority areas. Public health, children’s and adults social care budgets are facing significant demands and funding pressures.

Health and Wellbeing Board: a statutory committee of councils with responsibility for public health. It brings together NHS, public health, social care and Healthwatch to strategically plan health and wellbeing services based on the JSNA and JHWS. In some areas they have been subsumed by ICSs, in other areas they have retained a lead role within the new health landscape. District councils are not statutory members but in many areas are often part of the wider membership.

Voluntary, Community and Social Enterprise sector (VCSE): The sector is involved in the roll-out of social prescribing with some link workers employed by VCSE organisations and some organisations acting as a provider of social prescribing services. Medium sized organisations are likely to hold key relationships both across the sector and with the NHS and the wider public sector. The majority of VCSE groups and organisations are very small and lack the resources and capacity to proactively seek out referrals and join up locally. Furthermore, the differing size footprints between ICS and the VCSE sector and the sheer number of PCNs is making it challenging for some organisations to engage with health partners.

Providers: some councils have become the social prescribing provider or are funding and commissioning providers typically through the VCSE or prior to their abolition via Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs). Wider council services such as culture, parks, sport and leisure services also have a role to play in delivering social prescribing programmes. Whether that be through its infrastructure, existing or new activities.

Tips for success

- Have you invested time in understanding the current offer and developing relationships with partners? Map out and understand the current landscape – what are the strengths and weaknesses of the existing local offer? Which organisations already have strong community connections or are delivering social prescribing? Developing and embedding meaningful community partnerships needs an investment of time, so ensure this is built into your plans.

- How does it positively impact on your partners’ local priorities? Understanding the challenges facing your partners and demonstrating how social prescribing could positively impact on their priorities will help to win over your partners. Recent research shows that 81 per cent of social prescribing service users experienced positive change in at least one outcome measure ranging from improved wellbeing, skills development and improved employment/job prospects.

- Are your delivery partners funded and sustainable? Social prescribing is not free nor is it a cheap option, it needs to be fully resourced and sustainable. While social prescribing is a core activity of many arts, culture and leisure organisations they cannot continue to offer a high-quality offer without investment.

- Are your procurement processes inclusive, are you taking advantage of all the opportunities available to you? Some procurement processes can deter smaller arts, cultural and sports organisations from applying to deliver social prescribing contracts because they do not have the resources. Taking measures to ensure procurement processes are reasonable for the level of funding and opportunities are open and accessible to small and voluntary organisations can help overcome this. The procurement process also offers substantial opportunities to make full use of the powers of the Social Value Act and apply the Themes, Outcomes and Measures (TOMs) of the National Toms Framework ensuring that new contracts build in additional social value to communities, such as apprenticeships, outreach and activities targeted at less active groups, or purchasing from local businesses.

- What resources beyond funding can the council offer? For example, can you offer the use of a sports hall or other venue for social prescribing programmes to take place in?

Connecting into networks, support and funding streams

Much of the funding that has been made for social prescribing is allocated to increasing the numbers of link workers to meet the commitment for each PCN to have a link worker. Therefore it may be necessary to think creatively about grant funding opportunities and make the connection between social prescribing for culture, sport and green spaces. This will help to encourage new and diverse audiences through the door while improving their physical and mental wellbeing and sharing the joy of local collections, parks or leisure activities.

A range of support is available through a number of national organisations.

The National Academy for Social Prescribing (NASP)

Launched in October 2019 NASP works to create partnerships across the arts, health, sports, leisure and the natural environment. It is dedicated to the advancement of social prescribing through promotion, collaboration and innovation and provides a wealth of free research, evidence and tools. Community groups, arts, sports and leisure services may already have connections with NASP. It is likely that they are already accessing external funding which supports activity for health and wellbeing. The Thriving Communities programme led by and co-funded by NASP and other funding bodies is for voluntary, community, faith and social enterprise groups, supporting communities impacted by COVID-19 in England, working alongside social prescribing link workers. The Thriving Communities Fund, totalled £1.8 million, is currently closed to applications but the interim evaluation report offers learning and insights from the projects.

Accelerated learning in social prescribing programme

Launched in September 2021, the Accelerated Learning in Social Prescribing programme champions innovative ideas and approaches to social prescribing. The programme is a pioneering partnership between NASP, the Royal Voluntary Service and NHS England & Improvement. It aims to reach more people and transform more lives across the country, through innovative partnerships and approaches. The programme builds on social prescribing that is already taking place across the country. By connecting national and regional voluntary organisations to each other and to local partners, it promotes shared learning and helps grow new and more effective partnerships. At the heart of the programme is a virtual community of practice open to all national and regional voluntary organisations. It brings together members to grow, share best practice and celebrate the wealth of fantastic social prescribing activity, while forming partnerships to overcome challenges.

Culture Health and Wellbeing Alliance

The Culture Health and Wellbeing Alliance is a national membership organisation representing everyone who believes that creativity and cultural engagement can transform our health and wellbeing. It is free to join. It does not provide funding but it signposts to some of the organisations that provide funding for creativity and culture for health and wellbeing.

Personalised care

NHS personalised care approach means that some people with long-term conditions will be able to pay for local classes and activities (such as art classes, music clubs or a course at a local museum) as part of managing their own health and wellbeing, through their personal budgets. This gives people greater autonomy and moves away from a purely medical response to need.

National Lottery Community Fund

The National Lottery Community Fund distributes over £600 million a year to communities across the UK, raised by players of the National Lottery. Funding is available all year for projects run by voluntary and community organisations that support people and communities. Current funding has a focus on supporting the most adversely impacted by the pandemic. The Welsh funding programmes are open to public sector organisations as well as voluntary and community organisations. Funding from other National Lottery Funding bodies including Sport England and Arts Council England funding is also available.

Government departments and Arms Length Bodies

The Department for Digital, Media and Sport (DCMS), Department for Environment Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA) and the Department for Health and Social Care (DHSC) are working together with NHS England to support the national rollout of social prescribing.

Natural England are keen to promote the health benefits of the natural environment They are working with NASP to embed Green Social Prescribing (GSP) in social prescribing nationally. They currently have seven test and learn sites that are exploring various aspects of GSP.

Sport England’s 10 year strategy “Uniting the Movement” to transform lives and communities through sport and physical activity commits to working with partners on ‘connecting to health and wellbeing’ and supporting ‘connected communities.

Arts Council England is an administrator of funds which support social prescribing. It also supports culture-led health and wellbeing networks around the country including Arts and Health South West and the London Arts in Health Forum. Some operate on a local level, such as Leeds Art Health and Wellbeing Network, while some operate at a regional level, such as Arts Derbyshire and Arts and Health Network North East.

Prescribing to culture, leisure, sport and green spaces

With their emphasis on accessibility, wellbeing and community, arts, sport, parks, leisure services and museums are all well-placed to deliver on a range of policy objectives and contribute to local recovery strategies.

Prescribing to arts and culture

The arts can have a powerful impact on people with long-term health conditions. For example, music therapy reduces agitation and need for medication in 67 per cent of people with dementia. Many councils are already delivering social prescribing programmes such as arts-on-prescription and museums-on-prescription (sometimes known as referral programmes such as arts-on-referral). This involves people experiencing psychological or physical distress being referred (or referring themselves) to engage with the arts in the community including galleries, museums and libraries.

Arts on Prescription Gloucestershire has shown a 37 per cent drop in GP consultation rates and a 27 per cent reduction in hospital admissions. This represents a saving of £216 per patient The APPG on Arts, Health and Wellbeing Inquiry cites a social return on investment of between £4 and £11 for every £1 invested in arts on prescription.

Other examples of arts and culture social prescribing programmes include:

- Dementia cafes supported by the Alzheimer’s Society, these cafes have sprung up around the country – usually in museums, art spaces or libraries, offering people with dementia, and their carers, a safe, friendly place to relax and socialise and enjoy the sights on offer at the cultural venue.

- Knit and natter groups bring people together socially in a group where they are occupied and conversation can flow easily.

- Using archaeology to aid the recovery of military veterans: the Ministry of Defence launched Operation Nightingale in 2011 with the aim of involving wounded, injured, and sick military personnel and veterans in archaeological investigations as part of their recovery. One of the participating archaeological sites was Buster Ancient Farm in Hampshire, 26 volunteer veterans worked with archaeologists to build a traditional Bronze age round house. The build had a significant impact on the volunteers who took part.

“Working through each stage of the project has been brilliant and I still find it hard to believe how much my life has turned around because of it. Not just feeling myself again, gaining more independence and confidence, the comradery but what else the project has led onto.”

— John William Bennett, Royal Navy Veteran, 2021 Archaeology Undergraduate

Prescribing to libraries

Councils have a statutory duty to provide a comprehensive service, and to encourage both children and adults to make full use of the library service and to lend books and other printed materials free of charge to people living, studying, or working in the area. They are non-judgemental spaces that everyone in the community has access to, giving them a unique role in supporting people with health conditions, connecting and supporting communities. This is exemplified through the following examples:

- Reading well books on prescription (or bibliotherapy scheme) makes self-help books readily available to people to encourage greater understanding of their health condition and to learn how to better manage mental health issues such as anxiety and depression. Most libraries have a well zone where such books can be found.

- Reading groups encourage people to share their thoughts about particular books or simply to sit quietly and listen to a book being read – story time for adults if you like. While groups for children encourage them to see the library as a part of their community, offering as much or as little about books as they want but providing a social space for their parents and carers who may often find themselves socially isolated at home with young children.

Prescribing to sport

The link between exercise and health is clear. Sport can also offer other benefits through social prescribing, such as a sense of enjoyment and fulfilment, and helping people connect to others and their community. Exercise on referral is one of the earliest forms of social prescribing and is usually a programme where people with long-term health conditions such as diabetes, high blood pressure, or heart disease increase their physical activity levels by regularly using local leisure centres through GP and other referrals. Like with culture and arts, sports related social prescribing needs to be imaginative and varied, tapping into activities that support people who are experiencing a range of physical and mental health conditions and wider issues like loneliness or social isolation.

East Riding of Yorkshire Council’s exercise on referral scheme and the Live Well scheme continue to flourish with GPs able to refer directly via a secure e-referral system. The referral is picked up by the Central Team the day the referral is made, and they will attempt to contact the patient within 48 hours. While the exercise-on-referral is a set period of 10 weeks – Live Well can last up to a year. Over the past year about 1700 exercise on referrals have been made and 258 Adult Live Well referrals and 230 Young Live Well referrals.

Other examples include:

Singing can be its own exercise and can be beneficial to those who may, for example, have Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD).

- Swimming is a low impact exercise that can be done at an individual’s own pace and enhances mood and fitness.

Green social prescribing

Green social prescribing links individuals to nature-based interventions and activities, such as local walking for health schemes, community gardening and food-growing projects. The pandemic highlighted the importance of being outdoors to people’s mental and physical health as well as the inequality of access to private gardens and green spaces. Some innovative examples include:

- Gardening can provide a ‘dose of wellbeing’ as demonstrated by the Eden project’s social prescribing project “Nature’s Way”. The activity and creativity of working with plants and meeting others is helping to boost physical and mental health, reduce isolation and instil a sense of purpose.

- Partnerships and referral pathways between local mental health services and social prescribing can help to reduce demand on services and provide alternatives to traditional therapies.

Points to consider:

- Is your council’s culture and/ or sports and parks services maximising their contribution to social prescribing? How could this be developed? Can you broker introductions to health services or link workers?

- How can you support sports, arts and cultural organisations in your area to get involved in social prescribing or expand?

- What are the referral pathways into social prescribing activities? Could these be developed further or does it need to be streamlined? Is it a clear route and easy to navigate by service users and link workers?

- What are the key community spaces in your area? For example leisure centres or libraries, and can these be used to signpost people to a wider range of services and social prescribing opportunities?

- Who are the community leaders in your area? How can you work together to reach underserved groups?

Measuring impact

There is an emerging body of evidence that social prescribing can contribute to a range of local and national priorities, as outlined in the making the case section.

Measuring the impact of your social prescribing initiatives is a powerful tool for building the case for investment, as well as helping you to understanding the impacts you are having. There is not a ‘one size fits all’ approach to evaluating the impact of social prescribing but it is important to have consistency in the data that’s collated so that effectiveness can be assessed.

If possible, try to encourage local partners to adopt the same or similar evaluation frameworks so you can compare results. You may also want to think about how you can build the capacity of smaller organisations to measure impact, for example by sharing knowledge and resources.

For a comprehensive introduction to evaluation and the various tools available, the ‘Look I’m Priceless’ guide is helpful. Although developed in 2016, the Public Health England framework for evaluating the impact of arts programmes on health wellbeing is still relevant as is the Creative and Credible guide (2015). The New Economics Foundation’s guide for measuring impact on wellbeing is aimed specifically at voluntary and community organisations.

There is also more targeted guidance available, such as the ‘What works well for wellbeing’ guide to measuring impact on loneliness. UCL have developed a tool for museums to evaluate their impact on wellbeing and Sport England have created a comprehensive evaluation guide for sport and physical activity initiatives.

The NHS has developed an outcomes framework aimed at measuring three key aspects of social prescribing. All link workers employed by the NHS will be working with this outcomes framework, and it is therefore important to bear this in mind when designing local social prescribing programmes and evaluation processes. Make sure you are in regular dialogue with link workers and talk to them about how you can work together to support evaluation and share results for mutual benefit.

Supporting social prescribing in your area

We hope this guide has helped you to understand social prescribing, the role of arts and culture in its delivery, and that the case studies have inspired you to think creatively about the wealth of ways through which you can improve your residents’ health and wellbeing.

There are a number of common themes found across the case studies which may be helpful to bear in mind as you go forth and develop your local social prescribing offer.

- Local leadership is key to building across organisational boundaries – include PCNs, ICSs, ICBs, ICPs, voluntary and community sectors, social care and public health, GPs, link workers and local patient and carer groups.

- Consider your approaches to commissioning, is it accessible to community organisations already delivering social prescribing?

- Take a holistic approach - if you have not already done so, bring together organisations that include the arts, cultural and leisure sectors, to identify ways that all can contribute to improved health and wellbeing for residents

- The buy-in of senior leaders and decision makers is key to developing understanding, investment and support for the frontline.

- Make social prescribing a key focus for health and wellbeing boards and ICSs.

- Identify strategic and commissioning opportunities to advocate for inclusion of using arts and cultural and leisure providers to improve health.

- Nurture and invest in capacity especially of small organisations, support training and development initiatives for libraries, culture and leisure staff.

- Take contracting approaches proportionate to the value and complexity of the services being provided to avoid excluding small community groups.

- Small community groups need support, development and training rather than over complicated processes and regulation. Maintain close partnerships so that problems can be aired quickly and solutions reached.

- Consider your referral pathways, are they fit for purpose, are they maximising the opportunities or do they need to be simplified?

- Share and promote examples of social prescribing already in action.

- Offer in-kind as well as financial support. For example, offering a venue for activity sessions or office space at a reduced rate, or providing an IT platform to advertise community events. This can particularly help to build the capacity of small voluntary and community sector organisations and may unlock greater opportunities.

It is crucial to work in partnership with local health organisations and the VCSE to understand your current local offer for social prescribing. Then, you can identify key assets and gaps, and develop a strategy to sustain and grow the offer. Finally, be creative about grant funding opportunities from organisations like Arts Council England, Sport England and the Big Lottery Fund which might align with your objectives. The focus of these may be on culture (for example) rather than health but making the connection with wellbeing can help to encourage new and diverse audiences through the door while improving physical and mental wellbeing and sharing the joy of local collections, parks or leisure activities.

Further links and resources

Accelerated Learning in Social Prescribing programme

Launched in September 2021, the Accelerated Learning in Social Prescribing programme is an offer to bring together voluntary organisations with national reach (or ambitions) who can support social prescribing provision, help reduce health inequalities, and aid COVID-19 recovery strategies. It is a joint partnership with the National Academy of Social Prescribing and Royal Voluntary Service.

Culture Health and Wellbeing Alliance

Culture Health and Wellbeing Alliance is a national free to join membership organisation representing everyone who believes that creativity and cultural engagement can transform our health and wellbeing. They advocate, support local networks and provide resources including an extensive catalogue of case studies highlighting how arts and culture responded to the needs of the pandemic.

All-Party Parliamentary Group on Arts, Health and Wellbeing

The All-Party Parliamentary Group on Arts, Health and Wellbeing produced the Creative Health report, which contains a number of recommendations on how to best use the arts and culture sector when developing social prescribing. Among the recommendations is for Creative Health Champions to be appointed to board or strategic level to promote and encourage the use of the arts in health. So far there are 45 creative health champions represented in trusts, councils and clinical commissioning groups.

Organisations

National Academy for Social Prescribing

All-Party Parliamentary Group on Arts, Health and Wellbeing

Culture, health and wellbeing alliance

NHS England social prescribing learning network

National Association of Link Workers

About social prescribing

LGA guide on social prescribing models and local authorities

NHS social prescribing summary guide

Public Health England introduction to social prescribing

University of Wesminster guide to social prescribing

Mayor of London social prescribing resources

Culture and sport

WHO evidence review of the impact of arts on health and wellbeing

UCL e-learning course about culture, health and wellbeing

The health and wellbeing potential of museums and art galleries

Heritage and wellbeing scoping review

Case studies

- Alvanley Family Practice, Stockport

- Social prescribing on track, Cornwall County Council

- Arts on prescription, Doncaster Council

- Supporting residents with cultural commissioning, York

- Living well, East Riding of Yorkshire Council

- Wellbeing Exeter, Exeter City Council

- Nature’s way, Creativity at the Eden Project

- Hampshire Cultural Trust: Brighter Futures

- Thriving Communities, Oldham

- Self-help and social prescribing in libraries, Shropshire

- https://www.edenproject.com/mission/our-projects/natures-way

Acknowledgements

Thank you to everyone who contributed to the updating of this handbook, including;

Anne Rehill, South Downs National Park

Anooshka Rawden, South Downs National Park

Bev Taylor, National Academy for Social Prescribing

Collin Harker, Par Track Limited

Deborah Neubauer, Hampshire Culture Trust -

Dr Rupert Suckling, Doncaster Council

Dr Stephanie Tierney, University of Oxford

Emma Tolley, The Eden Project

Hazel Ainsworth, Natural England

Helen Apsey, Make It York

James Bogue, Exeter City Council

Jennifer Lonsdale, East Riding of Yorkshire Council

Jo Yelland, Exeter City Council

John McMahon, Arts Council England

Kay Keane, Alvanley Family Practice

Laura Windsor-Welsh, Action Together Oldham

Mairead O’Rourke, culturerunner

Mirka Duxberry, Shropshire libraries

Nathan Winch, Greater London Authority

Nicola Gitsham, National Academy for Social Prescribing

Samantha Ramanah, Local Government Association

Sarah Yelland, Devon Community Foundation

Trevor Creighton, Buster Ancient Farm

Victoria Hume, Culture Health & Wellbeing Alliance