Executive summary

Shared Intelligence (Si) was commissioned by the Local Government Association to capture learning for policymakers in central and local government from eight place-based programmes that have been delivered over the last 20 years. The programmes are (in chronological order): Local Public Service Agreements; Local Area Agreements; Total Place; Neighbourhood Community Budgets and Our Place; Whole-place Community Budgets; City Deals; the Troubled/Supporting Families Programme and Devolution Deals. Drawing on a literature review, 13 non-attributable semi-structured interviews and two sense-making workshops we have identified eight key lessons for policymakers to consider. They are:

Programmes such as these can add value, but there is a danger of bolt on, roll out, and move on.

There are real opportunities for councils which participate as pilots or in the first round of new programmes to secure considerable benefits from close engagement with government and the space for fresh thinking and innovation. They benefit most if they have a long-term vision or ambition for their area and use their participation to support action to deliver that vision.

Financial pressures can drive innovation, but they also erode capacity and exacerbate inequalities

Reductions in public expenditure can lead to cuts in councils' corporate capacity that is needed to lead programmes such as these. However, it is possible to secure improved outcomes at less cost through improved collaboration between agencies, a genuine focus on place and deeper engagement with communities. This requires intelligent use of evidence, an appetite to listen to the voice of the citizen and a commitment to prevention and early intervention.

Place is more embedded in government thinking, but progress requires a long-term vision and action across different geographies.

Impactful place-based activity is not a quick fix and often requires a flexible approach to geography and a willingness to treat boundaries as a spur to innovation rather than a barrier to action.

Communities and neighbourhoods are the building blocks of successful places and tapping into the citizens’ voice adds real value.

One of the most important lessons from the programmes we have reviewed is the value of tapping into the citizens’ voice and the lived experience of residents and their interaction with public services.

Relations with government are inevitably unequal but Westminster depends on local action to deliver its priorities.

Deals are useful tools but are not the result of a negotiation between equals. Government has the power and resources but often needs local councils to deliver their ambitions. The process of engagement with government can be a creative one, but Whitehall does not have the capacity to have a creative relationship with every council.

Evidence and intelligence are key ingredients of effective place-based activity.

These programmes demonstrate the value of in-depth analysis of financial and other information and have contributed to a significant evidence base of the value of early intervention and preventative activity.

Just how much value are pilots?

Pilot programmes can create the conditions for innovation but it is essential that lessons are captured and disseminated more systematically in order to influence mainstream practice in the longer-term.

Confident local political leadership is key to realising the benefits of programmes such as these.

If these programmes are to deliver more than incremental change ministers must empower strong local leadership and foster sustained collaboration between localities and Westminster.

Introduction and methodology

The last twenty years has seen a series of place-based programmes and initiatives most of which have been promoted by central government. The programmes were either billed as pilots or included a first round in which the approach was tested before being rolled out more widely. Many of the programmes were evaluated, but in too many cases lessons have not been learnt and there has not been a synthesis of findings from the programmes which would inform future policymaking. This report, commissioned by the LGA, is intended to help fill that gap.

The programmes we reviewed are (in chronological order):

- Local Public Service Agreements

- Local Area Agreements

- Total Place

- Neighbourhood Community Budgets and Our Place

- Whole-place Community Budgets

- City Deals

- Troubled/Supporting Families Programme

- Devolution Deals.

There were three elements to our methodology:

- Literature review: For each of the programmes in scope, we have reviewed the available national evaluations and other relevant literature. The results are set out in Appendix I, which summarises each programme and draws out key messages about what worked well and less well.

- Interviews: We carried out non-attributable semi-structured interviews with 13 people (listed in Appendix II) most of whom had been involved with planning or delivering at least one of the programmes. These were semi-structured interviews allowing interviewees to highlight key aspects of their experience and what they saw as the main lessons.

- Sense-making workshops: We held two online workshops with other people with knowledge of the programmes to test emerging findings and draw out further insights. A list of participants is included in Appendix II.

The following sections of this report comprise of:

- A short summary of each of the programmes and their legacy, together with a timeline and context.

- Our findings, using eight themes that we identified through the analysis of the literature review and interviews.

- A set of conclusions and key messages for policymakers today in central and local government.

- An appendix which summarises each programme, sets out their impact and signposts further reading.

The programmes

The scope of the programmes we have reviewed is summarised below and an example of the legacy of each programme is set out in Figure 1. More detail on each programme is provided in Appendix 1.

Figure 1: Legacy of each programme in relation to place-based collaboration

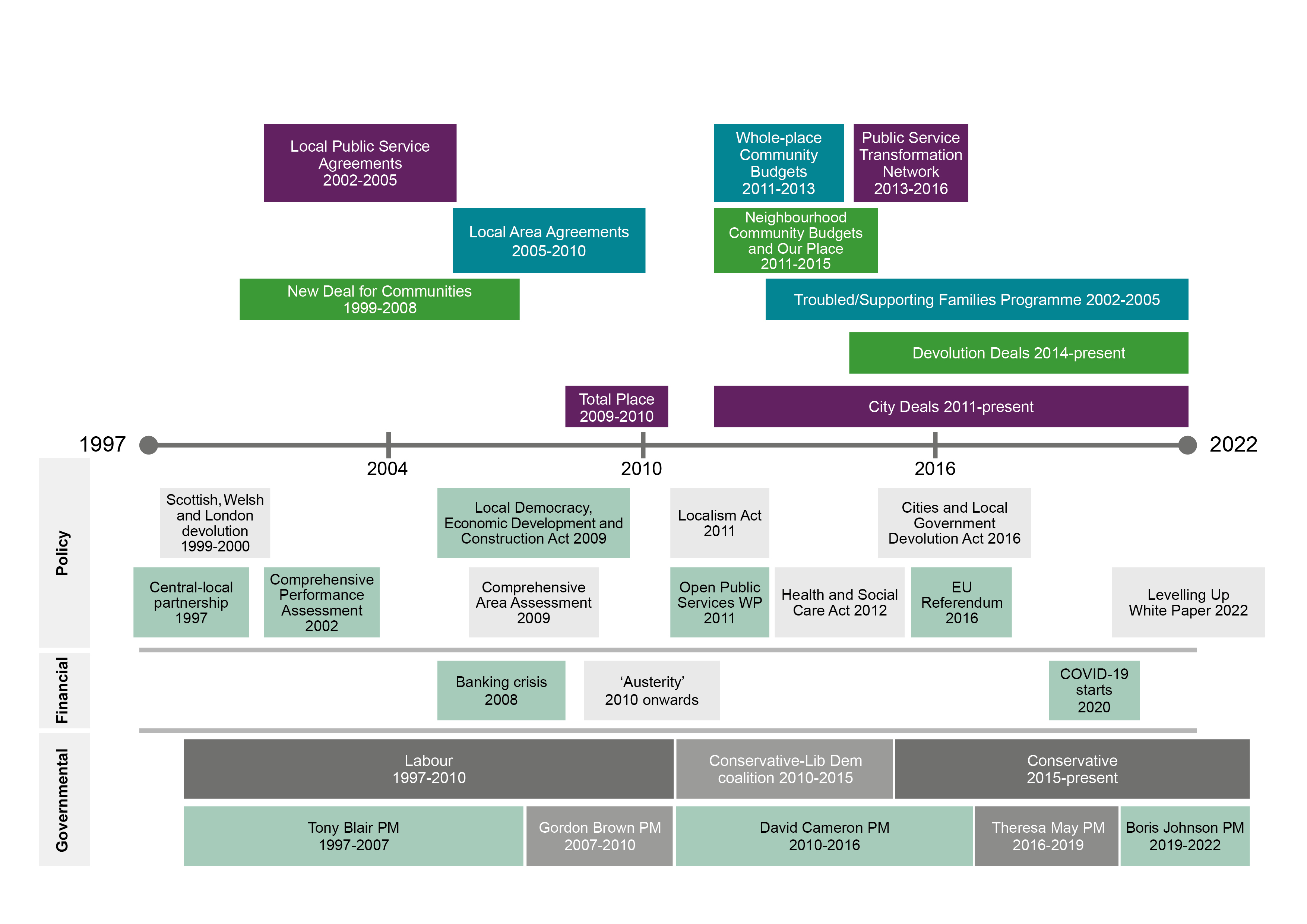

In thinking about the individual and collective impact of the pilots and first rounds of these programmes it is important to understand their historical and spatial context. The timeline in Figure 2 sets out the political, policy, legislative and financial context in which each of the programmes was launched. It shows the importance of the financial context and the way in which some elements have spanned several governments with, for example, the legislation enabling the creation of combined authorities being introduced by the Brown government but realisation of the concept beginning under the coalition.

Figure 2: Timeline and wider context for the eight in scope place-based national programmes

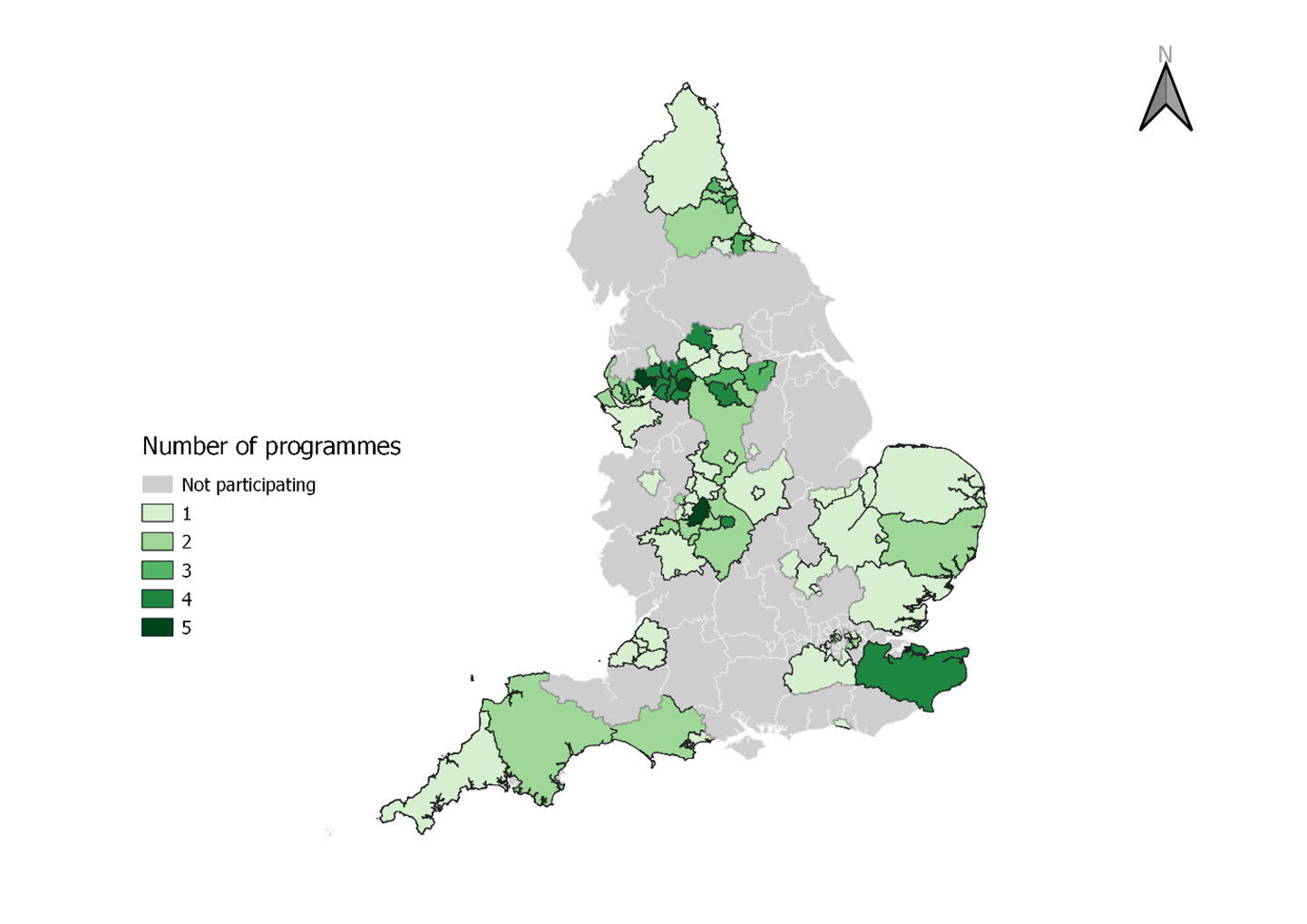

The map in Figure 3 shows the location of the pilots and councils which participated in the first rounds of these programmes. It is interesting to note that there are parts of the country in which no councils participated as pilots or in the first round.

Figure 3: Location of pilot areas in the first round of each in scope programme

The key elements of the programmes we have reviewed are:

Local Public Service Agreements

A mechanism for a local authority to negotiate around 12 targets with central government which would stretch achievement beyond that required by the then national performance regime. A 'performance reward grant' was made for successful delivery of this stretch.

Local Area Agreements

Aiming to incentivise local partnership delivery of stretching outcomes in areas of key importance locally, but which were consistent with national targets. They were seen as a lever to promote devolved decision-making, enabled by a negotiation with government.

Total Place

Sought to gain a greater understanding of how local public services were funded, with a view to strengthening the efficiency of public spending through joining up services. In re-designing service provision, strong priority was given to community engagement and citizen empowerment.

Neighbourhood Community Budgets and Our Place

Neighbourhood Community Budgets were developed to test how services and budgets could be devolved to the neighbourhood level and ran with 12 pilot neighbourhoods. Rebranded and extended as Our Place in 2014, local partnerships developed plans to tackle social issues identified by local people, receiving grants as well as specialist training and advice.

Whole-place Community Budgets

Piloted by four areas, including Greater Manchester and the West London 'tri-borough' councils , the programme developed from the central idea of aligning budgets to increase efficiency and sustainability of local services with a focus on social issues such as employment and skills, reoffending and health and social care. Each area produced an operational plan for change, supported by detailed business cases.

City Deals

A deal between central government and a city area providing specific powers and freedoms to help it support economic growth, create jobs or invest in local projects. Places were invited to set out their growth priorities before making their case to senior government decision-makers.

Troubled/Supporting Families Programme

The programme sought to improve support for families experiencing multiple and complex needs, with a priority focus on early intervention and prevention. It applied in all upper tier local authority areas. Designated keyworkers acted as one point of contact for all services which support the family, whilst also providing hands on and emotional support. The programme continues today as the Supporting Families Programme.

Devolution Deals

Devolution of powers and budgets to 11 areas in England for various purposes, including transport, learning and skills, and investment. For all areas, excluding Cornwall and London, this has involved establishing a Combined Authority that enables two or more councils to collaborate and take collective decisions across council boundaries.

The lessons

In this section we set out the key lessons from the programmes we have reviewed using eight overarching themes.

Programmes such as these can add value, but there is a danger of bolt on, roll out, and move on

It is inevitable that Westminster governments will launch new initiatives and programmes aimed at local councils and their partners. The issues they are intended to address involve deep-seated economic, social, and spatial challenges. There is therefore an onus on both central and local government to ensure that these programmes contribute to, rather than distract from, long-term action to address those issues. Some of the programmes we have reviewed, such as City Deals and Devolution Deals, are long-term endeavours. Others, such as Total Place, were time limited. There is, however, in relation to all these programmes a danger of bolt on, roll out, and move on.

A 'bolt on' is a new initiative, often one step removed from a council’s mainstream activity. A common theme of the evaluations of and personal reflections on these programmes is that innovation and creativity is a feature of the pilot stage or first round. This reflects a number of factors including the level of government engagement and the freedom to innovate at a local level that is often associated with pilot processes. The reference to 'roll out' reflects the experience in many of these programmes, including Local PSAs and Devolution Deals, that when an initiative is rolled out beyond the pilots, the conditions for innovation disappear and the process becomes more transactional and bureaucratic. 'Moving on' is the inevitable consequence of new initiatives being launched and too often leads to the lessons from the innovative phase being lost.

There are two key lessons for central and local government to ensure that places secure maximum long-term value from these programmes.

First, those councils which are pilots or are involved in the first round of a new programme should take advantage of the opportunity of close engagement with government and the space for fresh thinking and innovation. The evidence suggests that there are tangible benefits from this phase including, for example, joint posts, co-located activities, better use of evidence, new relationships, and a better understanding of local challenges within central government. It is important that explicit steps are taken to capture the lessons from this activity and, where appropriate, to consolidate and embed new ways of working. Steps should also be taken to disseminate this learning to the wider sector.

Second, those councils which have secured most value from initiatives such as these have a long-term vision and ambition for their area and have used national initiatives as a means of accelerating or strengthening action to deliver that vision. Greater Manchester is the textbook example of this. This means that councils participating in programmes such as these must do so with their strategic eyes open and push government to appreciate the importance of local calibration of national programmes to enable the long term local strategic fit.

Adopt national policy to meet your plans, not vice versa.

Former council leader

Financial pressures can drive innovation, but they also erode capacity and exacerbate inequalities

It is significant that six of the eight programmes we have reviewed were launched at times of tight controls over public expenditure. Total Place, for example, was launched against the background of the 2008 banking crisis and Whole-place took place in the context of the coalition government's 'austerity' drive.

The evidence from the evaluations of these programmes and the reflections of people involved in delivering them is that financial pressures can drive innovation. We also know, however, that reductions in public expenditure can lead to cuts in councils' corporate capacity that is needed to lead programmes such as these. They can also exacerbate the deep-seated issues, such as health inequalities, that these programmes are intended to address.

Total Place demonstrated that it is possible to secure improved outcomes at less cost through improved collaboration between agencies, a genuine focus on place and deeper engagement with communities. It is important to stress three important contributory factors that were features of this and other programmes:

- First, the need to distinguish between 'better for less' and 'more for less'. Experience shows that the former is a deliverable goal, but the latter is not.

- Second, the value of focussing on the totality of spend on a particular sphere of policy across an appropriate geography as a way of capturing evidence of the potential for different patterns of spend to secure improved outcomes.

- Finally, the centrality of early intervention, investment in prevention and investment in community-based (as opposed to institution-based) activity to so much of the work we have reviewed.

It is also evident from the programmes we have reviewed that three things must be in place if the goal of better for less is to be achieved: high quality cross-agency financial analysis; deep collaboration between public agencies and with citizens and communities; and high quality political leadership to make the case for change, including investment in early intervention and prevention - a theme to which we return later section in this report.

Place is more embedded in government thinking, but progress requires a long-term vision and action across different geographies

There is no doubt that place is more embedded in government thinking than was the case 20 years ago. It was a key strand of the National Industrial Strategy and features in the Levelling Up White Paper, the current reform of the NHS and in the Partnerships for People and Places programme. However, this rhetorical recognition of place does not always translate to government practice. Our interviewees and workshop participants cited aspects of the COVID-19 response as evidence of Whitehall’s centralising instincts – its default behaviour.

The evidence from programmes such as those reviewed in this report is that place-based action can help achieve national goals while enabling the delivery of a local vision and ambition. But two conditions need to be met, covering geographic boundaries and long-term vision.

It is important to recognise that different geographies are appropriate for different purposes. It makes sense, for example, to think about a skills strategy at a combined authority level, but universities, FE colleges, secondary schools and primary schools all have different footprints – as do hospitals and GPs. Too often boundaries are seen as barriers. The effectiveness of programmes such as those reviewed in this research hinges on the adoption of a flexible approach to geographies and the opportunity that cross-boundary work presents for innovation. To make this work, effort needs to go into developing a local infrastructure, involving citizens and communities, across different geographies.

Impactful place-based activity is not a quick fix: at different scales the New Deal for Communities, City Deals and Devolution Deals each demonstrate this. They also provide evidence of the importance of a long-term vision, of local agencies demonstrating what one of our interviewees called 'fidelity' to that vision and of avoiding being distracted by the “bolt on, roll out, and move on” nature of many national programmes.

Building an entrenched understanding of these conditions requires openness and dialogue between central and local politicians. Local politicians have a responsibility for making action sustainable by making participation in a national initiative part of the golden thread of a local long-term vision. But in return, national politicians need to allow their local counterparts the freedom and time to lead the local players to work together in a way that matches the needs of a place.

Government should provide LAs the tools to initiate projects and then let them lead themselves – this avoids initiatives weakening once government loses interest

Former senior civil servant and local authority chief executive

Communities and neighbourhoods are the building blocks of successful places and tapping into the citizens’ voice adds real value

One of the most important lessons from these programmes is the value of tapping into the citizens’ voice and the lived experience of residents including their interaction with public services. This is particularly so in relation to Total Place and Our Place. Those of our interviewees who were involved in Total Place point to its focus on more engagement with communities and citizens as being one of the most important and impactful elements of that programme.

Themes in relation to this topic that have emerged from our review of the literature, interviews and workshops include:

- The insights that are gathered by people such as GPs and councillors who have regular interactions with residents through their surgeries and, in the case of the latter, on the doorstep.

- The importance of community assets and investment in both meeting local needs and creating a sense of confidence in the place.

- The part that community action, such as befriending services, can play in preventative approaches.

- The value that the citizens’ voice can add to the interpretation of forms of evidence, helping councils and their partners to turn data into intelligence.

Connecting senior leaders to the people they serve locally can really change decision-making – providing a different angle on the data they see.

Senior local government officer

Authorities should go out onto the street and engage and survey communities more, and then use this evidence in local policymaking. They need to break the trend of just dealing with ‘business of the council’.

Former council leader

It is more challenging, but no less important, to secure community and resident engagement at a combined authority level. The use of social media and ethnographic approaches have been identified as two ways of doing so.

Relations with government are inevitably unequal but Westminster depends on local action to deliver its priorities

Our interviewees were clear that there are three features of working with government which must be taken on board by councils.

First, although deals and agreements are an important feature of many of the programmes we have reviewed, they do not involve a negotiation between equals: government has more power and resource.

Local government must focus relentlessly on creating better outcomes for citizens rather than trying to fight for a relationship with central government that Whitehall is unlikely to provide.

Former senior civil servant and council chief executive

Second, the link between ministers and their departments, together with the departmental accounting officer role of permanent secretaries, means that government finds it harder to join up than local councils do. Interviewees did, however, speak positively about the role of the Cities and Local Growth Unit.

Third, government does not have the capacity to work creatively with every council at the same time – hence the quality of engagement councils has secured as pilots and in the first round of programmes (compared with that experienced during the roll-out).

Despite these factors, there is significant value for councils and the places they serve in participating in these programmes. The process of negotiation with government may be unequal, but government depends on councils and their partners to deliver its ambitions – for example levelling up – giving them some significant skin in the game. Our interviewees were also clear that the process of negotiation was more fruitful to a council than simply responding to a menu or framework of opportunities.

The process of engagement with civil servants through these programmes is seen as having longer-term benefits for the councils and people involved and for public policy generally. It can only help the policy making process if more government officials have a better understanding of place and place-based working. Those involved in Whole-place, for example, spoke with enthusiasm about the role of government secondees in that programme and the mutual understanding they helped to nurture. They referred to the value of personal relationships over a decade after the initiative in which they were first established.

The impact of the engagement with government that these programmes provide depends in part on the political weather and councils’ understanding of that weather. Individual Ministers make a difference – with interviewees referring to the contributions of Michael Heseltine, Liam Byrne, Jim O’Neill, George Osborne, Greg Clark and Michael Gove – as do individual departments, with significant Treasury engagement widely seen as being a success criterion.

Local PSAs differ from the other programmes in one important respect: they were the result of ideas developed and promoted by the LGA. Similarly, councils in Greater Manchester had a significant influence over the development of combined authorities and devolution deals. More local government-led initiatives of this type would help to strengthen the hand of local government in its exploration with government of how to best secure improved place-based working.

Evidence and intelligence are key ingredients of effective place-based activity

Many of the programmes we have reviewed demonstrate the value of in-depth analysis of financial and other information informed by the citizens’ voice. In Bournemouth, Dorset, and Poole, for example, the Total Place pilot showed that many older people were in hospital unnecessarily, did not want to be in hospital, and that their needs could be met in other ways at less cost.

As we argue below, action on findings such as these requires confident local political leadership. It is important to stress two other features of the use of evidence in and following these programmes.

First, many of the programmes relate in one way or another to the importance of early intervention and investment in preventative activity. This often involves a shift in resource from other forms of activity which can be difficult to achieve, particularly at a time of financial constraint. It is important that the findings of these programmes are consolidated and used to inform future discussions on the case for shifting resource to this type of activity – the Total Place HM Treasury report for example highlighted the need for new freedoms to support investment in prevention.

Second, there is a danger of the use of data and evidence in these programmes being over-engineered, leading to tick box compliance and the bureaucratisation of programmes during the roll-out stage. Many of our interviewees and workshop participants considered that this was the case with Local Area Agreements and the Troubled Families Programme.

Just how much value are pilots?

One of the jokes among policymakers during the first half of the Blair premiership was that the government had more pilots than BA. As we noted earlier, pilot programmes can create the conditions for innovation locally and in government and in the relationship between the two, including the value of “test and learn” approaches which often form part of a pilot concept.

Pilot programmes can, however, be influenced by the process for selecting participants including the balance between the nature of the area, the performance of the council and the quality of the bid. Our interviews were mainly with early adopters and the architects of the programmes. These places had the benefit of pump-priming grant, dedicated Whitehall contacts or secondees and/or close Ministerial interest, which helped to create the capacity and conditions to focus on planning and delivering change. This may have contributed to a positive bias in our findings, but it is clear from our research that areas do benefit from participation in programmes such as this, particularly when doing so is used to help the place to pursue a longer-term vision.

Given the constraints of capacity in central government, there may be benefits in adopting simpler programmes with a menu of options following the initial pilot stage. This would lower the barriers to participation but risks a less innovative, more formulaic approach which is less likely to reflect local needs and priorities.

Wider benefits are often limited by the features of the 'roll out' stage we have highlighted above. But more serious are the constraints of the 'move on' phenomenon and the frequent failure to apply the lessons of programmes such as these so that they can influence mainstream practice in the longer term. Too often the findings in evaluation reports such as those we have reviewed for this research are forgotten in the rush to design or apply to participate in the next initiative.

Confident local political leadership is key to realising the benefits of programmes such as these

All of the programmes we reviewed have generated interesting findings with lessons for more impactful place-based working. Many of them have also led to some, essentially incremental, improvements in policy and practice. Then, as noted above, the government moved on to another programme or initiative. Many of the initiatives, most notably Total Place and Whole-place, made the case for more radical, more far-reaching change, including an increased role for early intervention and investment in preventative activity. Pursuing these approaches would involve significant changes in policy requiring confident local political leadership.

Local politicians are at their most powerful when they can demonstrate that they are transcending politics for a place and lofting the place debate above the political debate.

Former civil servant and local government chief executive

In practice this would also require national politicians to give explicit support to their local colleagues. This means deeper and sustained collaboration between localities and Westminster – the core, but as yet unrealised, ambition of these place-based initiatives.

Conclusions

Our analysis suggests that there are six key messages from these programmes for decision-makers in central and local government.

First, these programmes were most impactful locally when the council (or councils) involved had developed and was pursuing a long-term vision for the place. Ensuring the existence of an up-to-date vision, developed with partners, should be a priority for all councils and the existence of one should feature in the government’s criteria for participation in future programmes of this type.

Second, these programmes demonstrate the value of tapping into the citizens’ voice. This is best achieved locally and the opportunity for Whitehall to access this voice should be a driver of future collaboration between central and local government.

Third, there are wider benefits of deeper engagement between councils and Whitehall/Westminster including the development of long-term personal relationships, and programmes such as these are one of the ways in which they can be developed. To be of lasting value the relationships must extend beyond a gatekeeper or intermediary role and both tiers of government should pay attention to developing and maintaining them.

Fourth, pilots provide a 'creative space' for innovation and a 'test and learn' approach locally and nationally. These opportunities should not be confined to participants in programmes such as these. Thought should be given to how 'creative spaces' between central and local government can be created in other circumstances – as part of mainstream business, and not requiring the level of resource typically associated with some of the pilots we have looked at.

Fifth, several of these programmes ran when targets were a dominant feature of public service delivery. There are examples of how shared targets can focus and incentivise activity. There are also examples of how targets can distort activity through gaming and/or add to weaknesses of the 'roll out' stage we refer to above. Targets should be developed and deployed with care.

Finally, party politics is a key feature of the democratic environment in which both tiers of government operate, but the impact of these programmes demonstrates the benefits of transcending party-political divides in terms of both relations between ministers and council leaders and between councils at a local level.

Appendix 1: Summary findings from each programme in scope

The following findings notes about each of the eight programmes are based on a desk review of the available national evaluations and other salient reports.

Local Public Service Agreements

Summary

Local Public Service Agreements were the product of an LGA proposition, set out in The Local Challenge, in which the association argued that in return for significant freedoms councils would deliver real improvements for local communities in areas which both central and local government consider to be priorities. They were in effect a local manifestation of the national Public Service Agreements that set out government department targets for three-year periods under the Labour government from 1997 to 2010.

Under Local PSAs, a local authority negotiated around 12 targets with central government which would stretch achievement beyond that required by the national performance regime. A negotiation process between the local authority and central government sought to identify targets that addressed local and national priorities.

The concept of Local PSAs was launched in 2000 and negotiations took place with a pilot group of 20 local authorities. Roll out to all upper tier authorities began in autumn 2001. A second generation of Local PSAs began in 2003 and agreements were made with 58 councils, before being subsumed into the emerging Local Area Agreement process. This second generation of local PSAs had in any event focused on priorities for improvement locally, as agreed through Local Strategic Partnerships.

Central government asked for some targets in the areas of education, social care, transport and cost effectiveness. Other target areas reflected local priorities and the aim was to agree a joint set that reflected local and national considerations. 'Pump priming' grant was made available to the participating councils to support work towards the targets and a 'performance reward grant', up to 2.5 per cent of the council’s net budget requirement, was distributed in proportion to the level of achievement against the stretch targets, above a threshold of 60 per cent of the target.

A central plank of the programme was the negotiation of 'freedoms and flexibilities' with government departments which the councils expected would assist in the achievement of the stretch targets. It was envisaged that these would include the relaxation of reporting and planning requirements, changes to government rules, or best endeavours enabling support.

Overall impact

The national evaluation indicated that local PSAs did galvanise activity on specific service areas as a result of the combination of focus and incentives. As a crude measure of improvement, 57 per cent of the available performance reward grant was claimed in return for stretch achievement. The pilot councils particularly appreciated the opportunity to have a direct dialogue with government departments about how to address the challenges associated with the local delivery of the agreed priorities. Local PSAs closely influenced the subsequent development of Local Area Agreements, which extended the concept of reward grant, negotiated targets and freedoms and flexibilities in a local partnership context.

What worked well?

- The programme encouraged closer relationships and understanding between central and local government, particularly for parts of government that did not have active field forces in the regions. One example is of the Manchester health inequalities target leading to dialogue between the Department of Health and the Manchester joint health unit about data.

- HM Treasury involvement was very important for securing the engagement of Whitehall departments in the process.

- The relatively modest pump-priming grant was important – it provided capacity to plan, innovate and deliver change.

- There were spin off benefits expected in terms of data quality and use of data to drive performance.

What worked less well?

There were concerns that the process distorted the identification and delivery of agreed priorities in two ways:

- By focussing on outcomes that were measurable and on which councils were confident that they could maximise their financial reward.

- By constraining the pursuit of preventative activity because of the difficulty in agreeing indicators for this.

- Pilot councils questioned whether the target-led process would create the conditions for sustained improvement or new ways of working.

The negotiation process did not generate significant freedoms and flexibilities which was a source of disappointment. Two reasons were identified for this:

- That local councils were not very creative in what they asked for, were unrealistic or misunderstood what “freedoms and flexibilities” were all about.

- Some central government departments were resistant to change, underestimating how LPSAs were intended to influence ways of working.

Further reading

- National Evaluation of Local Public Service Agreements: Second Interim Report, Communities and Local Government, December 2006.

- Working Paper 3: Evaluation of Local Public Service Agreements: Central-local relations and LPSAs, Office of the Deputy Prime Minister, April 2005.

- Working Paper 4: Evaluation of Local Public Service Agreements: Exploring the Sustainability of Local Public Service Agreements: Office of the Deputy Prime Minister, March 2005.

- Working Paper 5: Evaluation of Local Public Service Agreements: First Target Owners Survey Report, Office of the Deputy Prime Minister, April 2005.

Local Area Agreements

Summary

The first Local Area Agreements (LAAs) were agreed with 21 local authorities in 2005. They were extended in two further waves until they covered all upper tier local authorities. They ran to 2010, when they were abolished by the coalition government.

LAAs aimed to incentivise local partnership delivery of stretching outcomes in areas of key importance locally which were consistent with national targets. They were seen as a key lever to enable devolved decision-making through negotiation with government. LAAs "required collective thinking and tough decisions about how best to focus effort and resources in support of the local ‘stories of place’ being developed across the country" (John Healey MP, Local Government Minister, Foreword to Deal or No Deal?: Delivering LAA Success by Anthony Brand, New Local Government Network, October 2008). A key difference between Local PSAs and LAAs was that the latter involved the local strategic partnership, not just the local authority.

LAAs were three-year agreements between local partnerships and central government and were negotiated under four outcome area 'blocks':

- Children and young people.

- Safer and stronger communities.

- Healthier communities and older people.

- Economic development.

They reflected a number of national indicators, as well as local, and included 'stretch' and 'unstretched' targets for each year.

The ambition was that the process would influence both mainstream expenditure and area-based funding to deliver the LAA outcome targets. In addition, a 'Performance Reward Grant' was available to areas for achieving their targets, although the available pot dropped from £1.5 billion in the first round to £340 million in the third.

LAAs were conceived in a policy context where increasing emphasis was placed on local partnership working. There was a new requirement for local authorities to lead the development of Sustainable Community Strategies (SCSs), and in some places LAAs were seen as part of the delivery mechanism for them. Local Strategic Partnerships were the local construct for agreeing SCSs and LAAs and a 'duty to collaborate' was introduced in the Local Government and Public Involvement in Health Act 2007 to require statutory local partners to participate. There was a significant emphasis on monitoring and, for most of their existence, LAAs operated in a context where Comprehensive Performance Assessment set out 198 national indicators for local government.

Overall impact

The evaluation of the first round of LAAs identifies benefits including:

- The creation of joint posts between agencies.

- The co-location of frontline teams.

- Jointly funded projects.

- Joint commissioning.

A longitudinal study of LAA round one areas, commissioned by the Department for Communities and Local Government, noted that it was difficult to attribute outcome improvements directly to the LAAs, but concluded that that improvements in satisfaction, or reductions in deprivation scores, could be linked to the 'holistic and targeted approach resulting from the inter-agency relationships and wider perspectives' with which LAAs and LSPs were closely associated.

What worked well?

- The rigour of LAAs helped to consolidate partnership working through a comprehensive collection of evidence and developing a 'story of the place'.

- LAAs provided a mechanism for driving visible cross-agency joint working – including shared posts and premises.

What worked less well?

- The LAA process was widely seen as being overly bureaucratic, a point that was stressed by the then Secretary of State, Eric Pickles, when he announced their abolition.

- There were concerns about accountability, including the role of backbench and opposition members and the lack of sanction for partners which did not deliver.

- As with Local PSAs, LAAs achieved little in relation to freedoms and flexibilities. Local areas did not define their requests well, and the government response showed little evidence of allowing local flexibility.

- Difficulty of delivering joined up government support. Negotiations with the government were channelled through Government Offices for the Regions. While this provided a single government voice and relationships were good, it did make for an 'indirect' relationship. Areas in the round 1 longitudinal study cited numerous examples where there were tensions between local and national views of targets, or perceived central reluctance to allow local agencies, such as JobCentre Plus to play a central role.

Further reading

- Deal or No Deal?: Delivering LAA Success by Anthony Brand, New Local Government Network, October 2008.

- Long Term Evaluation of Local Area Agreements and Local Strategic Partnerships: Case Studies Issues Paper, Communities and Local Government, December 2008.

- From Pilot to Phase 2: The ‘New’ Local Area Agreements, Centre for Local Economic Strategies Bulletin. This gives a summary of findings from two Office for Public Management (OPM) evaluations of the process of developing Local Area Agreements in the pilot and 2nd round pilot authorities.

Total Place

Summary

Total Place was launched in 2009 as a response to a recommendation of the national Operational Efficiency Programme but was not extended beyond 2010 by the new coalition government. It was intended to enable collaboration between public service providers at a local level in order to improve outcomes for local people and secure better value for public money spent locally. There were three related strands:

- Counting: pilots were used to conduct a 'count' of public expenditure in their place, including a “deep dive” into specific policy fields. This mapped the complexity of public spending across local partners and aimed to encourage discussion locally and nationally about how to improve the benefit of the spend within an area.

- Culture: Prevailing working culture that Total Place sought to address was that different agencies often targeted the same problem, with some 'owning' certain policy issues but resisting interagency collaboration.

- Citizen insight: This was intended to put citizens 'at the heart of service design' in order to direct funding to locally identified priorities: to achieve this, community engagement and citizen empowerment were prioritised.

Total Place was designed to pursue a diversity of approaches. Solutions were tailored to the varying needs of the 13 pilot areas which had a range of socio-economic and demographic characteristics and different local authority structures which in many cases spanned council boundaries. Each focused on a policy area that reflected local priorities, such as alcohol and drugs; older people’s services; and offender management.

Government was closely involved and a high-level officials’ group, chaired by Michael (now Lord) Bichard, supported and provided oversight for the work of Total Place at national level.

Overall Impact

Although the initiative only lasted 18 months, analysis of the pilots’ work is extensive, including a detailed Treasury report and reports from the Leadership Centre for Local Government examining the experiences of the pilots. This indicated that the programme was highly impactful in the short term.

What worked well?

The pilots produced strong evidence for change. For example:

- The value of a user point of view in demonstrating how services are fragmented and difficult to navigate.

- The use of inter-agency working and data sharing to prioritise preventative services, improving outcomes and reducing costs.

- The role of third sector organisations in facilitating community engagement, engaging citizens in service design as well as delivering services.

- Service managers working with staff and service users in designing their services led to innovative and creative ideas.

- Government deadlines meant that projects had to maintain pace in the face of sensitive and challenging issues.

- Local authorities began to feel less defensive and more confident in their dealings with Whitehall.

Total Place was popular because it was not imposed on anyone.

Former civil servant and council chief executive

What worked less well?

- A NAO 2013 report on the subsequent Whole Place initiative commented that Total Place (and its predecessor, LAAs), “have not led to large-scale and lasting change in how local services are organised, funded and provided.” This suggests that Total Place created energy, evidence and enthusiasm but that the impetus was not maintained, with government support, to create sustained system change.

Further reading

- Total Place: A Practitioner’s Guide to Doing Things Differently, Leadership Centre for Local Government, March 2010.

- Total Place: A Whole Area Approach to Public Services, HM Treasury, March 2010.

- Places, People and Politics: Learning to Do Things Differently, Leadership Centre for Local Government.

- Total Place Summary - Leadership Centre Website

Neighbourhood Community Budgets and Our Place

Summary

The Neighbourhood Community Budgets programme was launched in parallel with Whole-place Community Budgets in October 2011. It was its ultra-local corollary with an emphasis on supporting local people’s influence over neighbourhood level services and budgets and encouraging alignment with community group led action.

The programme ran from April 2012 to March 2013 in 12 selected neighbourhoods across England. Neighbourhoods were asked to create operational plans, supported by business cases. In July 2013, the programme was rebranded as 'Our Place' and extended to 141 communities with a package of support on offer, including grants of between £13,000 and £33,000, specialist training and advice and external programme management provided by Locality. Our Place was operational from January 2014 to summer 2015.

Developed in the context of growing budget pressures on local authorities and local service providers, Our Place shared some of the ambitions of the previous government’s Total Place programme, but at a neighbourhood level. It was intended to encourage local public service providers to look carefully at total public spending in a defined neighbourhood. Projects would then work together, with other interested individuals and organisations, to develop new collaborative approaches. An important aim was to encourage the pooling, devolving or 're-wiring' of budgets at a neighbourhood level with the aim of meeting community needs more effectively, and making savings to the public purse.

The projects were designed to be community-driven and often involved community organisations developing new ways to meet the needs of their communities, alongside the services provided by statutory organisations. Projects often focused on two sets of issues: health and well-being; and employment and skills. Examples included:

- A project in Torbay with an approach to social prescribing.

- North Huyton Communities Future aiming to create a new social housing ownership model to reduce the number of un-let properties.

- Stewkley Parish Council in Buckinghamshire taking on street scene services from the county council and using this also to meet the employment and skills needs of local young people.

Overall Impact

The aims of the projects under the initial and extended programme were diverse and a wide range of methods were used for community engagement and overall governance. The evaluations of both Neighbourhood Community Budgets and Our Place found that the model worked best when there was already a local pattern of statutory services supporting community-led change; where community organisations were already involved and experienced in practical service delivery; and where there were well-identified community needs, which could be a focus for innovation.

What worked well?

- The operational plans demonstrated the potential for neighbourhood level budgeting to offer significant efficiencies through community led service re-design.

- Our Place often saw community and voluntary organisations taking the lead in service provision. The support and funding provided through the programme was effective in building the capacity of such organisations and this resulted in projects that made a difference to the communities.

- Many areas achieved high levels of community engagement and developed new ways of working. However, the Our Place evaluation suggests that local authorities and other public service providers, such as local NHS bodies, were more supportive of implementation where financial values were small in proportion to overall service budgets or contracts. Cost benefit analysis helped build confidence among budget-holders.

- Both programmes set a tight timetable for pulling together the operational plans and the evaluations note the frustrations associated with this, including that it may have limited ambition. However, the pace provided focus and galvanised the community partnerships to deliver their plans – in two years from the start of the first round of Our Place, new service models were up and running and delivering outcomes.

What worked less well?

- There is a lot of emphasis in the evaluations on the difficulty of achieving pooled budgets. However, the work shows that trust can be built through alignment, virtual budgets and quick wins.

- Some felt that there were too many formal milestones to achieve – drop-out rates rose as the process progressed. Sustaining community engagement and input into the work was an on-going challenge described as needing clear governance structures, strong business cases, leadership, and dedicated and determined resources.

- Following on from Our Place funding, statutory services were reluctant to see services developed under the programme as replacements for existing services and therefore they were left with little prospect of receiving mainstream funding.

Further reading

- Community Budgets and City Deals briefing paper, House of Commons Library, May 2015

- Neighbourhood Community Budget Pilot Programme: Research, Learning, Evaluation and lessons, DCLG, July 2013

- Evaluation of the Our Place Programme: 2014-15: A report to Locality by Shared Intelligence, Shared Intelligence, October 2016

- Our Place: Internal Process Evaluation, Big Lottery Fund, May 2012

Whole-place Community Budgets

Summary

Whole-place Community Budgets were originally conceived to test the concept of creating a single pot comprising all local public service expenditure in a place to help local agencies work together more closely. The idea flowed from the July 2011 Open Public Services White Paper and the launch in April 2011 of a pilot programme for 16 areas to test 'Community Budgets' for families with complex needs. Whole-place sat alongside 'Neighbourhood Community Budgets' (covered separately in this appendix).

Following the publication of a prospectus in October 2011, the government selected four areas to pilot Whole-place: Cheshire West and Chester; Essex; Greater Manchester and the West London tri-borough area (Hammersmith and Fulham; Kensington and Chelsea and Westminster).

The pilots provided plans and business cases for redesigned services with detail about the expected improved outcomes and value for money. Co-design between local and central government was key to the way of working and the pilots were supported by civil service “counterpart teams”, and secondees. A 2013 report by the National Audit Office noted that the Department for Communities and Local Government provided £4.8 million from its annual budget to support the work of the pilots, which included funding for 33 senior Whitehall secondees.

In practice, the approach taken by the pilots shifted from the original single or pooled/aligned budget concept to focus on more specific outcomes such as reducing reoffending, preventing avoidable hospital admissions, and developing a more integrated approach to employment and growth. For example, Cheshire West and Cheshire developed six business cases expecting to deliver savings of £108 million over five years for an investment of £41 million. This included a new “assertive case management” approach to 525 troubled families; a council/health joint commissioning approach to children and young people, focused on prevention and early intervention; and a proposal for co-location of national and local employment support work in specific neighbourhoods.

The government supported the potential of the pilots’ business cases, but they were not made subject of a full-scale implementation or roll out. Rather several initiatives were put in place from March 2013 to sustain and expand momentum:

- Establishment of a Public Service Transformation Network, led from DCLG, which worked with 33 upper tier local authorities. The transformation network remained in place until 2016.

- Publication of a joint guide to Community Budgets with the LGA – this showcased the work of the pilots and highlighted their successful ways of working and tools used.

- Launch of a Transformation Challenge Awards competition with a focus on efficiency including back-office transformation.

Overall Impact

The work of the Whole-place pilots was impactful. The 2013 NAO report noted the robustness of the evidence produced in support of the business cases and Prime Minister, David Cameron’s foreword to the joint guide published in 2013 with the LGA stated: “Community Budgets have been shown to work”. The reality was more complex. An LGA commissioned report by Ernst and Young in 2013 extrapolated from the pilot business cases the potential for savings between £9.4 billion and £20.6 billion if the approaches were scaled up nationally. However, it and the 2013 NAO report, were clear that implementation at scale would be highly challenging; and implementation of the pilot proposals would rely on continued collaboration and clear leadership both locally and nationally in designing and implementing new services.

Whole-place Community Budgets were originally conceived to test the concept of creating a single pot comprising all local public service expenditure in a place to help local agencies work together more closely. The idea flowed from the July 2011 Open Public Services White Paper and the launch in April 2011 of a pilot programme for 16 areas to test 'Community Budgets' for families with complex needs. Whole-place sat alongside 'Neighbourhood Community Budgets' (covered separately in this appendix).

Following the publication of a prospectus in October 2011, the government selected four areas to pilot Whole-place: Cheshire West and Chester; Essex; Greater Manchester and the West London tri-borough area (Hammersmith and Fulham; Kensington and Chelsea and Westminster).

The pilots provided plans and business cases for redesigned services with detail about the expected improved outcomes and value for money. Co-design between local and central government was key to the way of working and the pilots were supported by civil service “counterpart teams”, and secondees. A 2013 report by the National Audit Office noted that the Department for Communities and Local Government provided £4.8 million from its annual budget to support the work of the pilots, which included funding for 33 senior Whitehall secondees.

In practice, the approach taken by the pilots shifted from the original single or pooled/aligned budget concept to focus on more specific outcomes such as reducing reoffending, preventing avoidable hospital admissions, and developing a more integrated approach to employment and growth. For example, Cheshire West and Cheshire developed six business cases expecting to deliver savings of £108 million over five years for an investment of £41 million. This included a new 'assertive case management' approach to 525 troubled families; a council/health joint commissioning approach to children and young people, focused on prevention and early intervention; and a proposal for co-location of national and local employment support work in specific neighbourhoods.

The government supported the potential of the pilots’ business cases, but they were not made subject of a full-scale implementation or roll out. Rather several initiatives were put in place from March 2013 to sustain and expand momentum:

- Establishment of a Public Service Transformation Network, led from DCLG, which worked with 33 upper tier local authorities. The transformation network remained in place until 2016.

- Publication of a joint guide to Community Budgets with the LGA – this showcased the work of the pilots and highlighted their successful ways of working and tools used.

- Launch of a Transformation Challenge Awards competition with a focus on efficiency including back-office transformation.

Further reading

- Whole-place Community Budgets: A review of the potential for aggregation, EY for the LGA, January 2013.

- Whole-place community budgets An LGIU essential guide, LGIU, July 2013.

- Local Public Service Transformation: A Guide to Whole Place Community Budgets, HM Government and LGA, March 2013.

- The Public Service Transformation Network, Public Sector Executive, February 2014.

City Deals

Summary

City Deals were announced in a White Paper, Unlocking growth in cities, published by the coalition government in December 2011. The emphasis was on supporting cities, and their wider economic areas, to drive economic growth, recognising that they were home to 74 per cent of population and 78 per cent of jobs. These figures were quoted in the White Paper and based on 2008 data, published in the Department for Communities and Local Government 2010 report 'Updating the Evidence Base on English Cities'.

They were intended to support a changed relationship between the government and cities – a means of empowering local leaders to drive economic growth and in particular to attract private sector investment.

The 'deal' aspect was fundamental to the concept and the white paper emphasised that the government wanted “genuine transactions, with both parties willing to offer and demand things in return”. The intention was that civic and private sector leaders should be able to argue for tailored new powers and funding to support economic competitiveness and innovative plans for growth. The government set out an illustrative menu of powers and freedoms to stimulate the negotiation, with a focus on the ability to invest in growth; the power to drive infrastructure development; and to support skills and jobs.

This was supported by the appointment of Greg Clark as Minister for Cities in a portfolio sitting jointly in the Departments for Business, Innovation and Skills and Communities and Local Government. He was supported by a new Cities Policy Unit in the Cabinet Office to drive co-ordination across government. The minister took a close hands-on role in negotiating the deals.

The first city deals were agreed in 2012 with England’s eight largest cities and surrounding areas outside of London: Greater Birmingham and Solihull; Bristol and the West of England; Greater Manchester; Leeds City Region; Liverpool City Region; Nottingham; Newcastle and Sheffield City Region.

The government had created Local Enterprise Partnerships (LEPs) in 2011 and they were closely involved in the design of the deals – one Wave 1 negotiation was LEP led; most of the others were jointly negotiated by the LEP and the local authorities. Greater Manchester’s was led by the Combined Authority.

In 2015, the National Audit Office estimated that Wave 1 involved government commitment of £2.3 billion of spending over a 30-year period with funding from eight departments.

The majority of funding was capital, and the deals had a long-term focus – 30 years in Wave 1. Precise plans for local economic growth varied, but there was a clear focus on skills and transport projects with every city region in Wave 1 including a skills programme in their deal and all but one including a transport programme. The largest Wave 1 programme was Manchester’s “earn back” arrangement, which will allow the combined authority to retain a portion of additional tax revenue generated by its investment which the NAO estimated to offer a potential value of £900 million.

A second Wave of 18 English City Deals followed in 2014 and further deals were agreed with city regions in Scotland and Wales. The Wave 2 deals were focused on a more limited number of programmes in each area.

Overall impact

Negotiation about outcomes was not new and had been part of the LPSAs and LAAs, including the aim to bring local and national priorities together. However, the NAO’s 2015 report on Wave 1 concludes that City Deals did represent a new way of working between local areas and the government as they gave places a chance to set out their own priorities and explain their growth plans directly to senior government decision-makers. They were the first 'deals' a concept that continues today with the county deals announced in the Levelling Up White Paper.

What worked well?

- By allowing local places a chance to present their own priorities direct to government, the deals were an important catalyst for cities to develop their strategies, capability and capacity to manage devolved funding and increased responsibility. Several went on the establish Combined Authorities. The Centre for Cities noted that City Deals helped to raise ambition within cities.

- The establishment of the Cities Policy Unit in the Cabinet Office provided cities with a direct point of contact in central government. The NAO found that cities felt that the unit helped make sense of the complex government landscape so that they could maintain alignment to their ambition and local priorities.

- The Centre for Cities found that private sector involvement in the deals helped to generate credibility for local government both with their local business base and with ministers.

What worked less well?

- The rapid pace of negotiations caused some problems. When agreeing the deals, the Cities Policy Unit did not always involve other departments whose involvement later would later be critical to programmes’ delivery. The Centre for Cities also noted that some areas did not have viable proposals ready when the invitation was issued – that said, the sense of urgency did also create a positive energy, helping to forge partnerships and generate agreement on joint priorities.

- NAO criticised the lack of a shared evaluation approach. In the context of such long-term arrangements, this makes it difficult to distil the impact of the City Deals on local economic growth.

Further Reading

- Unlocking growth in cities, HM Government White Paper, December 2011

- Devolving responsibilities to cities in England: Wave 1 City Deals, National Audit Office, July 2015

- City Deals, House of Commons Library briefing paper, July 2020

- City Deals - GOV.UK (www.gov.uk)

- City Deals, Insights from the Core Cities, Centre for Cities, February 2013

Troubled/Supporting Families Programme

Summary

The Troubled/Supporting Families Programme has had three iterations since 2012 and represents a concerted approach by the government to support the co-ordination of funding and services around the needs of the most vulnerable people. It was launched in March 2012 as a national programme involving all 152 English upper tier local authorities and was aimed at 'turning around' the lives of 120,000 families, with multiple and complex needs.

The first wave programme built on work with 16 pilot areas from spring 2011 under the original Community Budgets umbrella. That work had aimed to allow councils and their partners to pool various strands of Whitehall funding into a single 'local bank account' for tackling social problems linked to families with complex needs.

The full programme aimed to reduce the very high 'reactive' spend predicted to be associated with these families over life of the programme. The programme allocated £448 million of funding to encourage prioritisation of early intervention and prevention, data sharing and use of designated family keyworkers to facilitate joined-up, collaborative working. There was a payment by results element that councils could claim if they 'turned around' the family.

The second phase of the programme ran from 2015 to 2021 and had a wider reach, targeting 400,000 families with an emphasis on helping them to 'achieve significant and sustained progress against all their multiple problems' and to contribute to longer-term transformation of how public services work with these families. Councils received a service transformation grant to support deliver and there was a payment by results element of payment for success.

Since 2021, the work has been rebranded as Supporting Families with a focus on building the resilience of vulnerable families, and on continued enablement of system change locally and nationally.

Overall Impact

The programme differs from the others in scope for this study. Apart from its short initial pilot phase, it was essentially a national programme and had a cohort rather than a place-focus. Assessment of its impact in phase one was also controversial with criticism from the Public Accounts Committee for a claimed 99 per cent success rate in 'turning around' the target families. In response, in the second phase, the government extended the length of time over which family outcomes would be tracked, in order to focus on sustained change.

What worked well?

- From the first phase, the programme encouraged new more joined up ways of working with the target families with complex needs. The synthesis evaluation of the first phase describes it as a “catalyst for developing and investing in family intervention, at a time when fiscal constraints were being keenly felt”. As a national programme, it created a 'spotlight' that helped the Troubled Families Coordinators in achieving strategic buy-in at a local level.

- Benefits included better multi-agency work to identify and track families, and the employment aspect of the programme promoted better joint working between local authorities and JobCentre Plus at a local level.

- In the second phase, 86 per cent of Troubled Family Coordinators said the programme was “fairly or very effective” in achieving a focus on early intervention.

- Savings could be clearly demonstrated from phase 2. Setting aside impacts on Job Seekers Allowance, the evaluation estimated in 2017/18 that for every £1 spent, the programme delivered £1.94 in economic benefits, and £1.29 in fiscal benefits.

What worked less well?

- The first phase evaluation found mixed evidence about how effectively new ways of working were scaled up, with some evidence of loss quality of family intervention practice.

- The payment by results framework and targets in the first phase was contentious in many local areas and the evaluation noted some claims of perverse incentives.

- The impact of the first phase was also questioned. The evaluation noted that some families had achieved improved outcomes, but technically it could not find evidence of systematic impact' on the target areas of employment, benefit receipt, school attendance, safeguarding and child welfare over and above those experienced by a control group.

- Unsurprisingly for a large national programme, local variations have been a feature from the outset. The evaluation of the second phase continues to note varied performance across the country.

Further reading

- The Troubled Families Programme (England), House of Commons Library, November 2020

- National Evaluation of the Troubled Families Programme: Final Synthesis Report, DCLG, October 2016

- National evaluation of the Troubled Families Programme 2015-2020: Findings, DCLG, March 2019

Devolution Deals

Summary

The prospect of what became known as Devolution Deals was first trailed in September 2014 by the then Prime Minister, David Cameron. Alongside proposals for additional devolution to Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, he said: “It is also important we have wider civic engagement about how to improve governance in our United Kingdom, including how to empower our great cities”.

The first deal was announced in November 2014, for Greater Manchester. The city had agreed a statutory city region pilot in December 2009 covering transport, employment and skills programmes, housing and planning, low carbon, inward investment and innovation. It had also had a Combined Authority since 2011. The deepening of devolution in Greater Manchester and its commitment to the negotiation process played an important role in promoting and developing the devolution deals concept generally. The 2014 Manchester deal paved the way for an elected city-wide mayor who would also fulfil the role of Police and Crime Commissioner. New powers covered transport, business support, employment and skills, spatial planning, housing investment as well as earn back and governance reforms.

The devolution deals concept was given a wider push from 2015 by the Chancellor, George Osborne, with an emphasis on devolving local transport, housing, skills and healthcare to new combined authorities and elected city-wide mayors who should work with the local authorities in their areas. He wanted this to enable cities to grow their economies according to their own ambitions, and to ensure that “local people keep the rewards” (George Osborne, May 2015. Cited in Devolution to Local Government in England, House of Commons Library, February 2022). In terms of national guidelines, the objectives were very broadly framed – linked to support for economic growth and rebalancing, public service reform and improved local accountability. The message was that arrangements should be negotiated in response to local proposals.

To date, devolution deals have been negotiated with the nine mayoral combined authorities and Cornwall Council. All 10 are listed below with the agreement date of the first deal:

- Greater Manchester (November 2014).

- Sheffield City Region/South Yorkshire (December 2014).

- Cornwall (July 2015).

- Tees Valley (October 2015).

- Liverpool City Region (November 2015).

- West Midlands (November 2015).

- West of England (March 2016).

- Cambridgeshire & Peterborough (March 2017).

- North of Tyne (November 2018).

- West Yorkshire (March 2020 - a limited devolution “agreement” was made in 2015).

Although the specific terms and functions of each deal were not guided by a single template, there were core elements which were devolved in most of the deals. For example, each deal included an investment fund of between £15 million and £38 million annually which mayoral combined authorities could bring together into a 'single pot' alongside transport funds, the Adult Education Budget, the Transforming Cities Fund, and EU structural funds. Alongside this, a few regions agreed devolved powers on police and fire, justice, housing, and health.

Several areas have made subsequent deals which developed the extent and nature of devolution. In Greater Manchester there have been five deals since 2014 and arrangement now includes powers and resources in relation to health and social care, overseen by the Greater Manchester Health and Care Partnership. In the West Midlands, a second deal was agreed in 2017, giving the mayor and combined authority a greater role in driving the regional industrial strategy and additional funds for transport, skills and housing.

In a sign of a more formulaic approach to devolution, the current government’s Levelling Up White Paper includes a Devolution Framework with a menu of devolved powers linked to the governance arrangements a place is willing to introduce. The white paper also announced that two combined authorities, West Midlands and Greater Manchester would have an opportunity to negotiate more ambitious “trailblazer” deals.

Overall Impact

As the deals and governance models vary widely across the areas involved, it is difficult to draw out universal lessons. However, one clear message is that the devolution deals concept is an approach that needs careful nurturing and resource commitment to enable success. An NAO report from 2016, English devolution deals, highlighted concern about the ability of places living with reduced budgets to be effective in handling devolved responsibilities. A Shared Intelligence report in 2021 about lessons from the devolution deals highlighted how in many places a sustained effort was needed to build the required collaboration among stakeholders including councils, business and higher and further education. Similarly, commitment is needed from central government in committing capacity to negotiate.

Nevertheless, a 2016 New Economy report for the LGA about learning from devolution deals identified how the first deals should be seen as an on-going process involving further negotiation and implementation. Success is linked to the ability of areas to distil evidence-based strategic priorities which are shared by a broad coalition of partners.

What worked well?

- Agreeing a deal required a firm grounding in a clear and well-developed local strategy and narrative. In places, such as Greater Manchester and Tees Valley, deal agreement fits with the flow of many years of collaboration across the same geography. A 2019 Devolution Deal Impact Assessment for Cornwall highlighted how the achievements of its deal linked to the existence of co-terminous boundaries among public sector partners enabling it to exploit the freedoms of the deal to collaborate on tackling cross-cutting issues such as deprivation and the ageing population.

- Where key components align across the area, there is a sense that devolution deals have been the beginning of a process creating influence beyond formal powers. A 2018 University of Manchester study about learning from the health and social care reforms in Greater Manchester described this as a form of “soft” devolution. While it was cautious about the benefits it may bring in the future, it predicted it would create pressure “to close the gap between statutory legal position and the facts on the ground”.

What worked less well?

- The negotiation of deals appeared to lose steam over time. While early deals were seen to have been an important and creative process, a finding from the 2021 Shared Intelligence report was that government ambition declined leading to more formulaic approach with less willingness to consider new elements. A National Audit Office study from 2016 noted a concern among the local areas it had interviewed about the capacity of the government to maintain sustained commitment from all relevant government departments. There was some evidence that not all government departments fully bought into the negotiations. The 2016 New Economy report describes red lines relating to national post 16 and skills-based programmes and a lack of consistent departmental buy-in to devolution across government.

- There is a fine balance between central guidance and allowing local vision to flourish. The NAO noted that the absence of a government prospectus about options for opportunities led many areas to be guided by the precedent of previous deals to identify what they were likely to be able to achieve.

- Three of the originally proposed deals were not agreed – for the whole North East area (not just North of Tyne); for East Anglia; and Greater Lincolnshire. The reasons are highly nuanced in each case but indicate the dependence on clear and widely accepted area vision as a prerequisite for success.

Further Reading

- Devolution to local government in England, House of Commons library, February 2022

- Learning from English devolution deals, New Economy, July 2016

- Evaluation of Devolved Institutions: BEIS Research paper number: 2021/024, BEIS, May 2021.

- Devolution Deal to Delivery: a guide to help councils navigate devolution deals, Shared Intelligence, July 2021.

- English devolution deals, National Audit Office, April 2016.

- Cornwall Devolution Deal Impact Assessment, Cornwall Council, CIOS LEP and NHS Kernow CCG, 2019.

- Devolving health and social care: Learning from Greater Manchester, The University of Manchester, 2018.

Appendix 2: Interviewees and workshop attendees

Interviewees

Helen Bailey, Chief Executive, London Borough of Sutton and former HM Treasury official.

Lord Bichard, Former local authority chief executive, permanent secretary and chair of the Total Place high level officials’ group.

Sir Merrick Cockell, Former leader of the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea and former chairman of the LGA.

Adam Hawksbee, Deputy Director and Head of Levelling Up, Onward.

John Jarvis, Chief Operating Officer, Leadership Centre.

Dr Peter Kane, Former Head of Local Government Team, HM Treasury.

Lord Kerslake, Former local authority chief executive and former head of the home civil service.

Sir Richard Leese, Former leader of Manchester City Council.

Colin Noble, Former leader of Suffolk County Council

Robert Pollock, Chief Executive of Cambridge City Council and former senior civil servant.

Joe Simpson, Former director, Leadership Centre and Principal Strategic Adviser, Local Government Association.

Tom Walker, Executive Director, Essex County Council and former Head of Levelling Up Task Force.

Patrick White, Director, Metro Dynamics and former director of Local Government Policy, in DCLG.

Attendees

Laurence Ainsworth, Head of Public Service Reform, Cheshire West and Chester Council.

Chris Bally, Deputy Chief Executive and Director of Corporate Services, Suffolk County Council.

Jean Candler, Head of Policy and Public Affairs, Bristol City Council Bristol City Council.

Michael Coughlin, Executive Director, Surrey County Council.