About mentoring

All of our improvement work is informed by the concept of sector-led improvement, meaning that it is peer-led and involves councillors and officers helping each other to improve. Sector-led improvement is based on the underlying principles that local authorities are:

- responsible for their own performance

- accountable locally, not nationally.

It works on the principle that there is a sense of collective responsibility for the performance of the local government sector as a whole, with the role of the LGA being to provide tools and support, including commissioning councillor and officer peers to provide that support via our regional principal advisers and political lead peers.

Overview

Many councillors and political leaders have benefitted from being involved in our peer support activities, by serving as LGA peers themselves or by working alongside LGA peers. Mentoring is an important way in which we can further contribute to improvements in the quality of political and managerial leadership to build capacity and support and to increase the role effectiveness and performance of councillors at all levels.

Benefits

Mentoring aims to benefit all parties involved in the process, including the mentor. The primary aim is to build the capability of the individual mentee so that all those involved in the outcome benefit – the specific local authority, fellow colleagues, and the wider local government sector. The benefits for the mentor include further developing skills that will make them a more effective leader in their own council and other working environments, including developing new councillors and future leaders.

Common elements

There are common elements relevant to all mentoring activities. Each activity is designed to build leadership capacity and is based around an individual learning agreement, which involves a planned and defined approach and should result in clear outcomes. These outcomes should be robust and capable of review and analysis so that measurable progress of the individual is achieved.

Support and management

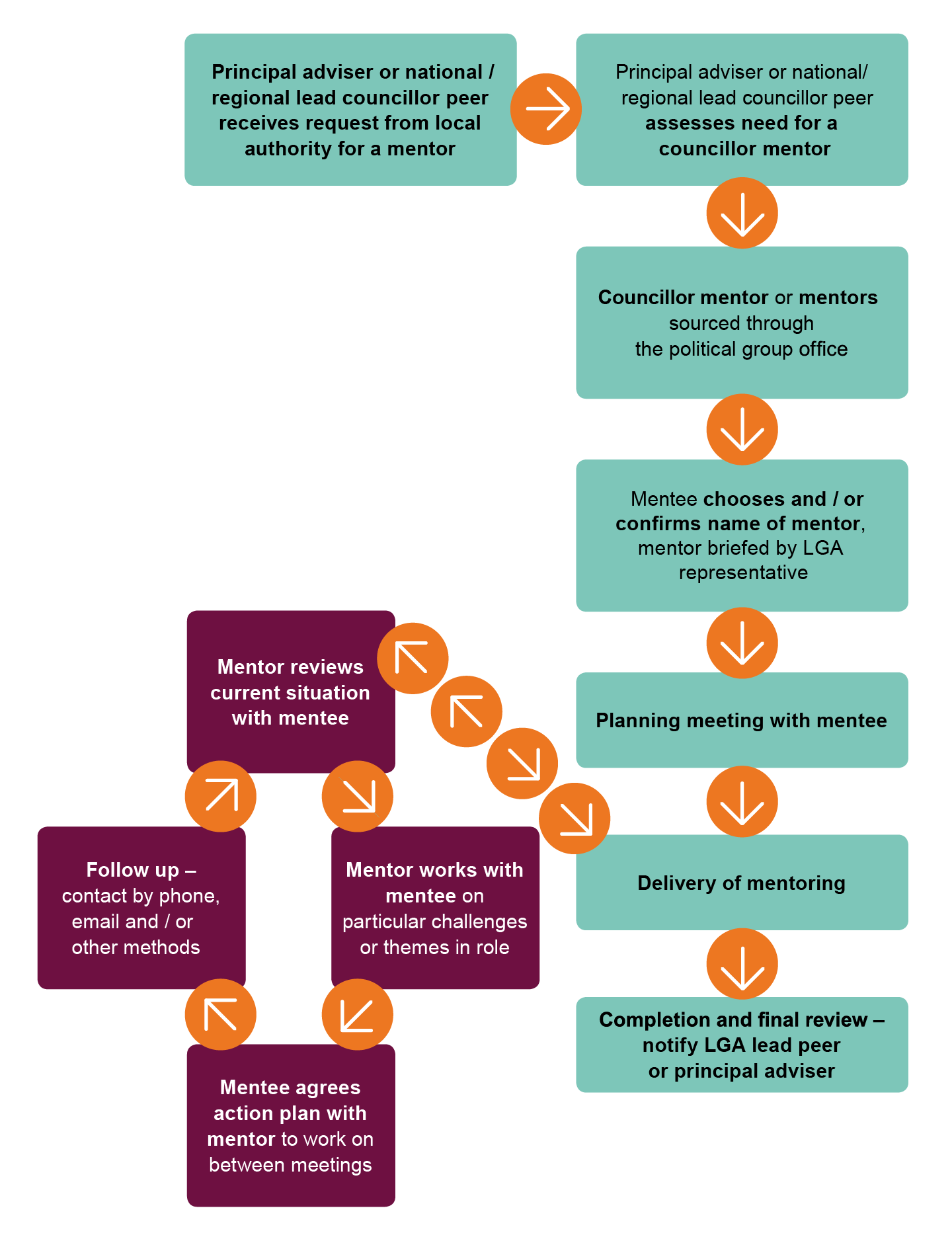

National and regional lead peers

Our national and regional lead peers help to identify mentoring opportunities within local authorities in which their help is needed to support and develop councillor support programmes. They also suggest how our range of mentoring activities can actively support the political leadership of the council.

Principal advisers (for the regions)

Our regional principal advisers, with the assistance of their teams, scope out and negotiate the programme of mentoring with a local authority, and commissions our LGA political groups to supply suitable potential mentors.

The mentoring relationship

This section covers your mentoring relationship in more depth. It outlines the principles that underpin your work as a councillor mentor and summarises your main responsibilities, skills and qualities required. It also outlines the practical arrangements for starting your mentoring activity. This includes information on planning and the paperwork to help you plan the agreed actions and review the progress you make with your mentee/s.

Mentoring principles

Our councillor mentoring model has been developed around a number of key principles. These will help inform the evaluation the programme and underpin your work with the mentee to ensure an effective and productive relationship.

Mentees must be in control of their own learning – the mentor’s prime purpose is to meet the mentee’s needs and provide benefit to them within their environment:

- the mentee’s needs must be met within the context of achieving the council’s corporate objectives, building leadership capacity and increasing their effectiveness within their role

- the relationship requires confidentiality between mentor and mentee and should be based on mutual trust and respect

- the scope and structure of the mentoring will be mutually agreed between mentor and mentee

- mentors should manage the mentee’s dependency, ensuring that disengagement occurs at an agreed time, in accordance with the mentee’s needs, but within the scope and duration of the mentoring as agreed by the council and an LGA representative at the start of the process

- the mentoring relationship should balance both being politically partisan with objective support to improve the role effectiveness of the individual

- mentors should develop a non-supervisory or performance management relationship with the mentee. It is not the mentor’s role to instruct or check up on the mentee’s work – rather to guide and support in their work as a councillor

- mentors should support behavioural change where necessary to ensure that political standards, probity, and ethics are observed.

Mentor responsibilities

The role of the councillor mentor will involve an element of constructive criticism. You should understand the importance of the ‘critical friend’ ethos particularly where there is a requirement for you to challenge attitudes or behaviour. Providing sufficient opportunities within the relationship for ongoing reflection will also benefit the mentee. And the relationship will be helped if mentor and mentee have specified and agreed the mentee’s desired outcomes at the outset.

The mentoring agreement will help mentor and mentee to structure those outcomes at the start.

Mentor skills and qualities

These can be summarised as an individual who:

- is committed to making the relationship work at all levels

- listens as much as questions

- challenges as a ‘critical friend’

- encourages reflective learning

- is motivated to feedback and pass on know-how

- is capable of identifying and expressing improvement options

- is able to provide advice on specifics

- is a guide and catalyst for mentee networking opportunities

- is a gateway to other people’s experiences and sources of knowledge

- is respected and trusted.

If you have received training in mediation skills and techniques, you can also use this experience to navigate hostile, complex, and disruptive political relationships to the benefit of the council, party and individuals concerned.

Planning for mentoring

Careful planning and preparation for your mentoring activities is essential. Gathering as much information about the individual mentee or group to be mentored, their organisation and the environment in which they work beforehand will be of great value. The briefing from the LGA principal adviser, senior regional adviser or regional lead peer will be key to gaining this information and intelligence and will take place soon after you are notified that you have been selected as mentor.

For example, newly elected councillors will have a range of mentoring needs including getting to know who’s who, dealing with officers, constituents, and the media, coping with time management, balancing their workload, paperwork, and information and communications technology (ICT), and keeping proper records.

In addition to making the most of the time available to you, it will help you to prepare for the relationship and think about the desired outcomes before you start the activity. This preparation will help you to be more effective and might differ depending on the mentoring option you use.

Ground rules for the mentoring relationship

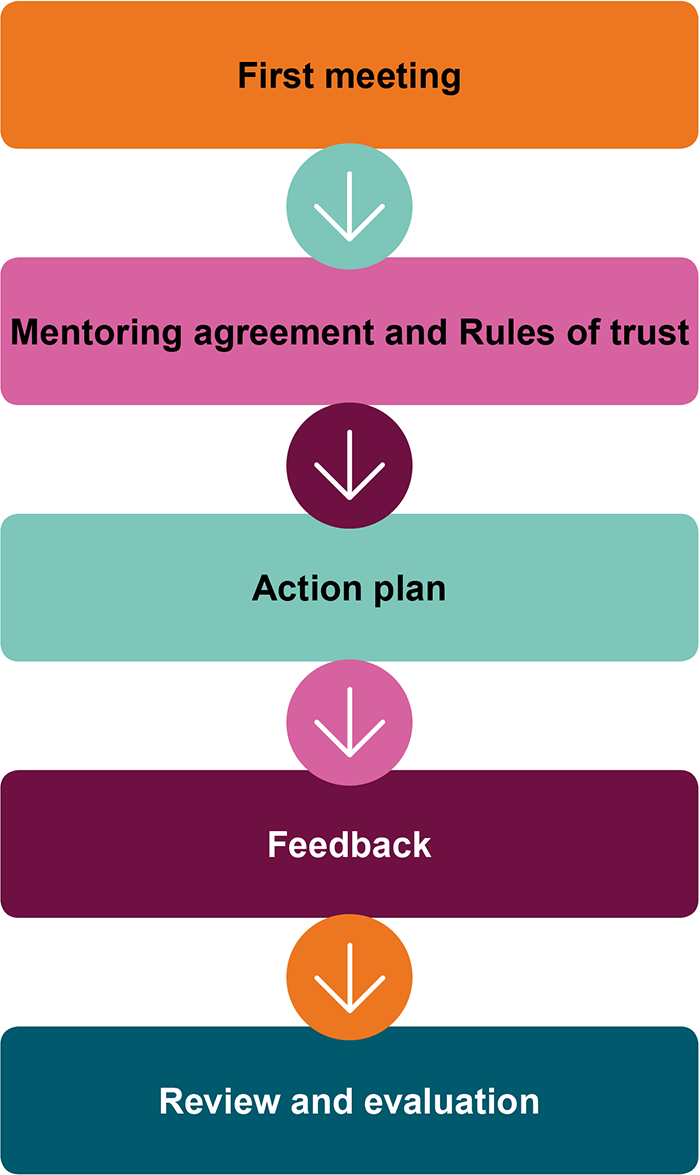

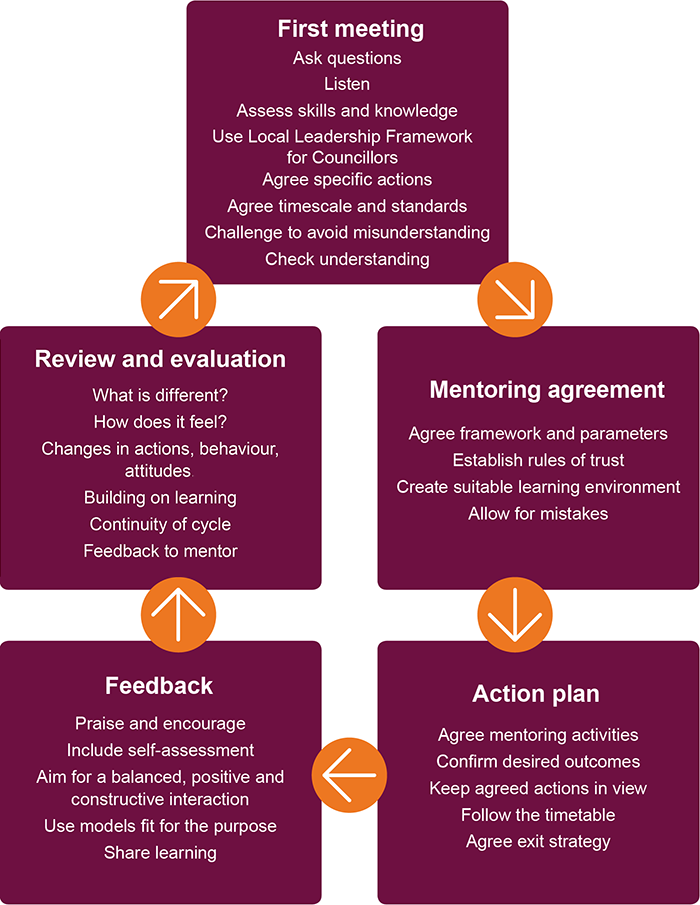

First meeting

Your first meeting sets the scene and enables you to begin building rapport with your mentee. It is at this initial meeting that mentor and mentee should also identify the skills set areas that the mentee wishes to develop to improve their performance as a councillor.

Mentoring agreement

The Mentoring agreement is a document that mentor and mentee should use to at the start and during their mentoring relationship to ensure they identify and address what they need to (see the 'Downloadable forms to track mentoring progress' section below for details of the Mentoring agreement and to download a template Mentoring agreement form). A Mentoring agreement should be established with an individual mentee or group and will provide a valuable framework and plan in which development and achievement can be jointly monitored during the stages of the mentoring activity. It establishes the benchmark against which the success of the mentoring relationship is measured. The mentoring agreement will also help establish the rules of trust that should be inherent to your mentoring relationship and ensure that mutual respect is engendered, and confidentiality maintained. The rules of trust include:

- the mentor and individuals / groups will establish a relationship based on trust and honesty

- any information obtained because of the mentoring relationship will be deemed to be confidential unless the parties involved give clear permission for information to be used outside the relationship

- it is the responsibility of the person / persons being mentored to keep the mentor informed of changes of circumstance.

Action plan – mentoring activities

When you have covered all the ground rules and your mentoring agreement is in place you will be ready to proceed with the development of the action plan. It is the mentee’s responsibility to ensure that the plan stays on track and to take the necessary steps along the way to ensure that the agreed actions stay clearly in view. The route you take will be dependent on which mentoring activities you are involved in although there are common factors applicable to each action, for example, keeping to regular appointments and agreeing when the mentor support will be completed. In summary, the action plan should:

- record when and where mentor and mentee/s will meet to set out the learning that all parties feel needed to support the development of individuals or groups and how that may be enabled

- plan and record the exit strategy at an appropriate time as agreed by all parties

- identify a set aside time for the mentor to seek mentee feedback on the process and reflect on the performance of both parties.

Feedback

Providing feedback to the individual or group you work with, both positively and constructively, is vital to the success of the mentoring activity. This ensures that you as mentor remain fully aware of how the mentee is finding the process, and if necessary, alter your practice to meet their needs. Mentors should also work with mentees to do some self-assessment of progress, as well as reflect themselves on their own performance. An LGA principal adviser or senior regional adviser may also seek mentee feedback on how things are going.

Planning for mentoring – the five stages

Resources for practical support

The resources below provide a set of practical learning tools with which to plan, problem-solve, assess skills, and analyse individual behaviour in your role as a councillor mentor. This does not preclude you from using other techniques that you have found helpful in your mentoring experience to date.

Experience in practice

The role of mentor is specialised – you not only need to understand the roles and responsibilities of councillors, and guide them in their personal development, but also to understand:

- the analytical tools that are available to help assess individual learning styles and preferences and how to use them

- which behaviours will help or hinder learning to take place.

Some of the councillors you mentor might have experienced using some of these analytical tools and techniques and / or questionnaires before. If so, they should be encouraged to share the outcomes with you. If the questionnaires are new to the councillor/s, you might suggest that one is completed as part of the ‘getting to know you’ process, in preparation for your second meeting.

Kolb's learning styles and experiential learning cycle, for example, is an accepted and well-regarded model that helps remind us of the importance of learning from experience. The concept of ‘action learning,’ developed by Kolb, forms the basis of many of the techniques featured here.

The GROW Model is a widely used model for coaching and underpins many subsequent frameworks. Although, during mentoring sessions, we might ask different questions, the model provides a powerful framework for navigating a route through a mentoring session.

GROW is an acronym for the four key steps in GROW coaching:

- G for goals

- R for reality

- O for options

- W for will.

Through effective questioning and discussion, a mentor can quickly raise awareness and responsibility in each area:

The key is to set a goal which is inspiring and challenging, as well as SMART (specific, measurable and achievable in a realistic time frame). Then move flexibly through the other stages, including revisiting the goal if necessary.

The final 'will' element is the barometer of success. It converts the initial desire and intention into successful action.

The GROW Model is designed to promote confidence and self-motivation. With the intention that it will lead to increased engagement and personal satisfaction.

Models and questionnaires

The models and structures are best used in conjunction with the Local Leadership Framework for Councillors to help you decide which technique is most appropriate in each mentoring situation. They each address a wide range of requirements in the mentoring relationship – the need for structured questioning and listening, behavioural analysis and ‘reality checks,’ skills assessment, planning and problem-solving.

You can find more information about these resources in the 'Further reading' section below. You can use these resources in your mentoring work and relationships with mentee/s or they can be used by the mentee on an individual basis to help identify opportunities for personal improvement. They should be seen as a suite of potential tools to use, rather than a prescriptive model. Once you have completed the Mentoring agreement with your mentee and you start work on improving the competencies as agreed, you can use various models and processes to help.

Kolb's learning styles and experiential learning cycle shows that it is necessary to follow through on the learning and development process, building in planning and reflection to promote positive outcomes and reduce mistakes. The period of reflection during the ‘think about it’ stage in the mentoring relationship is important to ensure that agreed actions and progress are discussed and that failure to meet agreed learning objectives is avoided.

A competency model can be used to reassure mentees that we learn in incremental stages before we can do things automatically. Explaining the process by which we move from one level of competence to another can help demonstrate that how we learn is as valuable as what we learn.

The Johari Window is a similarly useful tool, which is best used in one-to-one sessions as a means of exploring areas of an individual’s behaviour that affect their professional effectiveness. It is designed to give individuals a picture of themselves in relation to others, so that they can achieve their objectives more readily. It can help explain why, for example, a councillor is not attaining the outcomes that he/she expects – clarifying in simple terms, the difference between conscious and unconscious behaviour and its impact on working relationships. In addition to working together to identify conscious and unconscious behaviours that affect performance, it can be helpful for mentees to reflect on how they are seen and then

compare this with an observer’s perspective.

The managing time questionnaire is designed to highlight areas where time management is an issue. Councillors inevitably lead very busy lives and time management techniques can help them to make the most of the time available and become more efficient. This may be completed by the mentee in preparation for a meeting with you and can help you identify the most appropriate approach for enhancing the mentee’s skills with respect to time management and more broadly.

Radiant thinking or mind mapping, scenario planning or visioning

Cost benefit analysis (CBA) planning and problem-solving techniques can be variously used to stimulate ideas, remove blockages in thought processes, find new ways of expressing ideas through plan for action and to evaluate advantages and disadvantages of a course of action in relation to expenditure, people, and time.

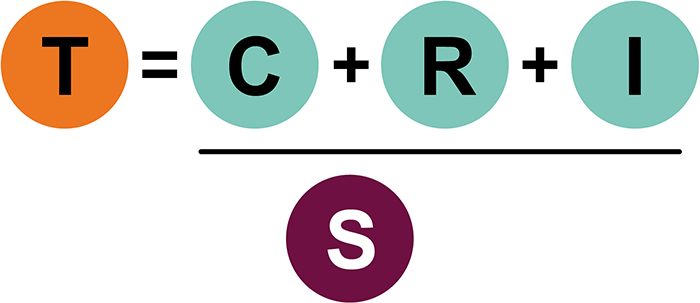

The Trust Equation

The traditional view of a mentor is that they are more senior or hold a higher status in the organisation. In fact, the principal role of the mentor is as a trusted adviser, supporter, teacher, or wise counsel. All of which could be fulfilled by a peer. The only requirement is that the person has knowledge and experience that they can pass on to the mentee.

Maister, Green and Galford in their publication, ‘The Trusted Advisor’, describe a way of quantifying ‘trust’ with the following equation:

- T for trustworthiness

- C for credibility (words)

- R for reliability (actions)

- I for intimacy (emotions)

- S for self-orientation (motives)

The Political Skills Councillor Toolkit, based on the Local Leadership Framework for Councillors, will allow mentees to review their current skill levels and how often they need to use them. This will help them to identify their development priorities.

The Gibbs Reflective Cycle

The Gibbs Reflective Cycle from Learning by Doing: a guide to teaching and learning methods by Graham Gibbs is a reflective model based on several stages, during which you are required to answer several questions to go as deep as possible with your reflections. Gibbs suggests the following stages: description, feelings, evaluation, analysis, conclusions, and action plan.

Mentoring issues

There are any number of factors that can diminish the mentoring experience for you and for your mentee, therefore it is worth becoming aware of the most common ones, so that you can try to avoid them or take remedial action if you find yourself affected by them.

Julie Starr, in her book ‘The Mentoring Manual’, lists five common factors:

- putting yourself under too much pressure

- having an agenda

- feelings of superiority or prestige

- low levels of engagement

- dependency.

Putting yourself under too much pressure

As you have put yourself forward as a mentor, it is more than likely that you feel it is important to succeed in the role. A problem arises when that obligation to perform reaches a point at which it can have the opposite effect. This can result in issues such as:

- reduced abilities to think clearly

- behaviours such as talking too quickly or over-explaining

- tension, tiredness, or frustration.

These arise from a gap between what we would like to achieve and our perception of how we think we are doing or have done. It is worth remembering that, whilst you do not want to minimise the importance of the role you are playing, not all conversations will go as you would like, and you will not be able to answer all questions posed by your mentee.

Tips for maintaining a balance between healthy and unhealthy pressures

These include:

- have an open dialogue with your mentee about what they want from you and what you feel you are capable of delivering

- develop a positive mindset by focusing on what is or has been going well rather than on perceived difficulties

- recognise that success in the relationship is not solely down to you but is a collaborative effort

- don’t become fixated by creating or achieving successful outcomes. These are in the control of the mentee, not you.

Having an agenda

Having an agenda for your mentee such as, ‘What they really need help with is x’ or ‘What they need to do or achieve is y’, is likely to be counterproductive. If you have any of these thoughts, this is likely to result in you:

- over-emphasising or narrowing down conversations onto topics you think are important

- offering a lot of advice on a topic of little interest to the mentee

- being selective in your listening

- displaying impatience.

If the mentee does not share your vision, this can lead to the mentee feeling uncomfortable or disengaged from the process, or it may lead to a loss of self-confidence.

Of course, as a mentor, it is your role to introduce ideas to help the mentee achieve their goals. However, to see a single idea as the one and only solution might prevent you from listening to what the mentee perceives they need. Certainly, introduce ideas into your conversations; that is what the mentee will expect, but you are likely to be of more benefit to your mentee by adopting a listening approach and responding appropriately. The key to this is ‘staying in the moment’. When listening, avoid thinking about how you are going to respond, or how you are going to make your point once the other person has finally stopped talking. Void your mind of other thoughts and listen to what is being said and how. This is the art of ‘deep listening’.

Feelings of superiority or prestige

Achieving an open dialogue and free exchange of ideas during mentoring conversations can only be achieved if both parties believe there is equality within the relationship.

If you are conscious of an inequality in terms of status, power and influence, there is always the possibility, unless you guard against it, that this will influence the way you relate to your mentee. Typically, this will manifest itself in behaviours such as speaking down to them, e.g. simplifying your language or concepts, giving them instructions, or perhaps, in terms of transactional analysis, adopting the ‘parent’ ego state in any discussion.

The less control the mentee feels they have, because their mentor is adopting a dominant role, the more likely they are to disengage from the process.

The way to avoid this is to become self-aware. Be clear about:

• your motivation for being a mentor

• your objectives in the mentoring relationship

• your thought and feelings in the moment

• your behavioural drivers

• the impact events or situations are likely to have on your feelings.

Low levels of engagement

Any of the above factors could result in low levels of engagement from the mentor or the mentee.

From your perspective as a mentor, this could manifest itself as cancelling meetings at short notice as you respond to other priorities, a lack of willingness to give practical help, a lack of energy or rigor during meetings, or clear signs that you are not enjoying the experience.

Some of the reasons for this could be:

- other pressures outweighing the benefits of mentoring

- a failure to see what’s in it for you

- anxiety around the role or the relationship

- a lack of observed progress or improvement from the mentee.

Once again, being self-aware is essential if your lack of engagement is not to impact negatively on your mentee. Question your own motivation as a mentor and investigate the cause of any negative feelings. Where appropriate, talk to your mentee about their experience and whether they are still getting benefit from the relationship.

From the perspective of the mentee, low levels of engagement could result in a lack of effort in taking actions, blame for lack of progress directed at you or at themselves, or low levels of self-esteem and confidence.

Responding appropriately is important. If you identify that the problem is on your side it would help to explore the issue with your mentee as a step towards resolving the problem. If you feel that the problem sits with the mentee, you need to raise the issue in a way that does not compound the causes. Try not to be accusatory when you do address issues.

Avoid statements such as:

‘Why haven’t you completed any of the actions you committed to at the last meeting?’

Use instead objective observations, such as:

‘I notice that you haven’t managed to complete any of the actions we discussed at the last meeting. There must have been a reason for that. Would you like to talk about it?’

The purpose is to avoid being seen as judgmental or disapproving. If the mentee has not completed the actions they initially committed to, there will have been a reason. You are far more likely to get a comprehensive explanation if you invite the mentee to share. A fuller explanation gives you something to work with in trying to remove any blockages.

Dependency

It is important during any mentoring relationship to maintain a degree of distance, that is, not to become reliant on each other.

The goal for the mentee is ultimately empowerment, so you need to ensure that your mentee does not become dependent on you for:

- ongoing praise and encouragement

- support in making decisions

- feelings of wellbeing or euphoria following your conversations.

Similarly, the mentor should not become dependent on the relationship for positive feelings about:

- being needed

- their professional standing

- the level of influence they can exert on the mentee.

In either case, there may be a tendency for the relationship to continue long beyond its useful purpose. For the mentee, they need to be able to move on independently.

Added to this might be some of the challenges created by the way in which we frequently work in local government, in which not all your interactions will be done face to face.

Mentoring remotely

Since the COVID-19 pandemic, we have moved increasingly to holding many meetings online. There are, no doubt, numerous benefits to this approach. Including a saving in time, reduced environmental impact and greater flexibility. The downside, of course, is how the process of building relationships is impacted, which is integral to successful mentoring. While many of us feel we can build and sustain relationships without meeting face-to-face, not everyone feels that way.

In addition, for some, there may be accessibility issues. Those with visual or hearing impairment, for example, may feel more comfortable meeting in person, while others who live in busy households or share accommodation may not have a suitable place from which to conduct sensitive meetings.

These are issues that might be discussed at the chemistry meeting.

Julie Starr offers us these principles for our mentoring journey:

Your relationship is one of equality and yet has a natural bias / emphasis

Your role is to provide support and guidance to help the mentee grow and progress, while increasing their sense of empowerment. This is a collaborative process. An imbalance of power and an emphasis on status can get in the way of that process. The natural bias or emphasis comes from the fact that you, as the mentor, inevitably have more experience in some areas than the mentee. This should not be used to ‘manage’ the mentee.

The responsibility for learning, progress and results ultimately rests with the mentee

This naturally follows from the first principle. If the mentee is to feel empowered, they have to have the responsibility for the learning journey. Whilst it is normal for a mentor to want to help the mentee to achieve success, the mentor needs to beware of this becoming a ‘personal agenda’. The measure of success for the mentor is the ‘level of support offered’ not the ‘success achieved by the mentee’. This principle should be discussed early in the process.

Mentoring is a collaboration between you, your mentee and ‘everyday life’

We have already mentioned that this is a collaborative process. However, the inclusion of ‘everyday life’ in the principle above is a reference to the fact that real life will intervene during the mentoring period. It is possible that the process will start with, say, the mentee wanting to achieve promotion but deciding later that a role with fewer demands would be a more appropriate goal. The mentor is not in control of this change in direction, but they can still provide a valuable role in helping the mentee achieve success, whatever that now looks like.

Ultimately what your mentee chooses to do, learn, or ignore from the mentoring is not the mentor’s business

In line with the principle of helping the mentee feel empowered, we have to accept that the mentee might choose to ignore our advice. If we have made an emotional investment in the mentoring process, as is likely as we get to know the person better, we may feel frustrated if the mentee chooses a path different to the one, we recommend. The key to staying true to this principle is to remain ‘interested’ in what the mentee does, not ‘invested’ in it. We have to be careful that we don’t let our egos get the better of us.

Some results of mentoring can be identified or measured, while some cannot

At the start of the process, we help the mentee define, as part of their objective setting, how they will measure success. This question is likely to be an important part of crystallising the mentee’s thoughts around their goal; ‘What does success look like?’ However, while we would like to be able to measure the output from the mentoring exercise, if only to justify the time, effort, and cost, some of the impact may not be obvious. For example, the mentee may exhibit an increasing level of confidence, introspection, or determination over the course of the exercise. This shift, which might not have been the primary objective, might only become apparent over time and, indeed, would be difficult to measure. That doesn’t mean the results are any less significant than the initial objective.

Further reading

A list of publications and online resources that may support your work as a councillor mentor:

Bibliography

- Arnott, J. and Sparrow, J. (2004) The coaching study, Birmingham: University of Central England.

- Buzan, T. (1989) Use your head, London: BBC Books.

- Buzan, T. with Buzan, B. (1993) The Mind Map, London: BBC Books.

- Casey, D., Roberts, P. and Salaman, G., (1992) 'Facilitating learning in small groups' in Leadership and Organizational Development Journal, Vol. 13, No. 4, pp. 8–13.

- Clutterbuck, D. (1995) Counselling adults – making the most of mentoring, London: Channel 4 Television.

- Clutterbuck, D. (2004) Everyone needs a mentor, 4th Edition, London: CIPD Books.

- Clutterbuck, D. (2002) Learning alliances – tapping into talent, London: CIPD Books.

- Coates, J. (1994) Managing upwards, Aldershot: Gower.

- Covey, S. !1992) The seven habits of highly effective people, London: Simon and Schuster.

- Garvey, B. (2004) 'The mentoring / counselling / coaching debate' in Development and Learning in Organizations, Vol. 18, No. 2, pp. 6–8.

- Gibbs, G. (1988) Learning by Doing: a guide to teaching and learning methods by Graham Gibbs (free online resource), Oxford: Oxford Polytechnic (now the Oxford Centre for Staff and Learning Development at Oxford Brookes University).

- Hagemann, G. (1992) The motivation manual, Aldershot: Gower.

- Handy, C. (1994) The empty raincoat, London: Century.

- Hay, J. (1995) Transformational mentoring – creating development alliances, London: Sherwood.

- Hay, J. (1997) Action mentoring, London: Sherwood.

- Jeffers, S. (1996) Feel the fear and do it anyway, London: Century.

- MacLennan, N. (1995) Coaching and mentoring, Aldershot: Gower.

- Maister D., Green, C. and Galford R. M. (2002) The Trusted Advisor, London: Simon and Schuster.

- Megginson, D. and Clutterbuck, D. (1995) Mentoring in action, London: Kogan Page.

- North, V. with Buzan, T. (1993) Radiant thinking, Bournemouth: Buzan Centre Books.

- Rogers, C. (1978) Carl Rogers on personal power, London: Constable.

- Rogers, C. (1965) Client-centred therapy, London: Century.

- Rogers, C. (1961) On becoming a person, London: Constable.

- Sloman, M. (2003) Training in the age of the learner, London: CIPD Books

- Starr, J. (2014) Mentoring Manual – your step-by-step guide to being a better mentor, London: Pearson.

- Stewart, V. and A. (1982) Managing the poor performer, Aldershot: Gower.

- Warner, J. and Suff, P. (2004) E-learning – management best practice, London: Work Foundation.

- Woodcock, M. (1989) Team development manual, 2nd Edition, Aldershot: Gower.

Online resources

- Local Leadership Framework for Councillors | Local Government Association

- Chartered Management Institute (CMI)

- Coaching and Mentoring Network

- Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development

- Kolb's learning styles and experiential learning cycle | Simply Psychology

- What is a competency model? | Valamis

- The Johari Window | MindTools

- How good is your time management questionnaire | MindTools

- Mind mapping and radiant thinking | Bill Synnot and Associates

- Cost benefit analysis | Bennett Institute for Public Policy, University of Cambridge

Downloadable forms to track mentoring progress

The mentoring agreement

The mentoring agreement is the foundation for successful mentoring activities. It should be completed during the individual meetings and used to help create a positive relationship between the mentor and mentee/s:

- identifying individual/group leaning needs, aims and objectives

- setting out expectations and responsibilities

- agreement on what actions will support the mentoring

- identifying any practical resources required

- final review and reflection of learning objectives.

Satisfactory matching of mentor to mentee is crucial. If either participant is concerned that after the first meeting the match is not appropriate, they should contact either their political group office or regional principal adviser or the authority’s liaison person (in the case of the mentee) so that an alternative mentor can be found.

Completing the mentoring agreement

The mentoring activity will have been agreed within the context of the authority’s circumstances and the wider member development. It is important when agreeing actions that both mentor and mentee understand what these are. If these have not already been communicated, the project manager and/or authority liaison person should be asked to supply details.

The progress review section should be used at relevant points during the mentoring relationship to support reflection and agree changes where necessary.

The final review section is to be completed by the mentor at the final meeting with the mentee.

In agreement with the mentee(s), the completed learning agreement and final review will be used to support the evaluation of the mentoring activity and discussed with the client authority.

The mentoring agreement includes the following information:

- name of mentor

- name of mentee/s (if a group, please give group name)

- name of local authority where mentoring is being delivered

- type of mentoring being delivered.

Download Mentoring agreement form

Progress review form

This form is designed give a structure for the mentor to guide the mentee/s to:

- focus on the actions that have been taken place in the intervening period between meetings, by asking them to describe what went well and what had been difficult

- identify the key areas of learning

- identify with their feelings about the actions

- look at what actions they were unable to take and why

- concentrate on what they would do differently following the actions that they took

- draw up their next action plan.

The progress review form asks: Do you need to adjust the action plan in the light of what has happened?

If so, please return to section 4 of the mentoring agreement to revise, as necessary.

Final review form

This is designed to help the mentor to guide the mentee/s to:

- reflect on the overall effects of the mentoring support in terms of supporting personal learning and development as well as general progress and key areas of learning

- consider what they would do differently as a consequence of the mentoring.