About this report

WPI Economics is an economics, data insight and public policy consultancy. We are driven by a desire to make a difference, both through the work we undertake and by taking our responsibilities as a business seriously.

We provide a range of public, private and charitable clients with research, economic analysis and advice to influence and deliver better outcomes through improved public policy design and delivery.

This research was commissioned by the Local Government Association.

We would like to thank all those who contributed their time and valuable input into this research, with specific thanks to Local Partnerships and ADEPT, which offered advice and support throughout the research process.

Foreword

Tackling climate change is one of the world’s biggest challenges. The next decade will be critical for protecting our environment, enhancing biodiversity, and ensuring that we create sustainable, resilient places and communities in all parts of the planet.

Now is the time to strengthen the role of regional and local government in delivering international and national climate ambitions. Councils want to work as partners with Government to tackle climate change. They are integral to transitioning our places and empowering our communities and businesses to a net zero future and are well-placed to deliver transformative local action. This is through their many powers and responsibilities in housing, planning, transport, procurement and as convenors of local partners and residents.

Councils are already taking a leading role on decarbonisation and at a time when they are resetting following the pandemic, driving a green recovery. Over 300 local councils have declared a climate emergency and the National Audit Office found that almost two thirds of councils in England are aiming to be carbon neutral 20 years before the national target.

This research focuses on some of the key areas that councils have significant influence over to reduce carbon emissions, such as housing, transport and renewable energy projects. It provides the strategic and economic case for why and how councils can unlock economic, social and environmental value through the delivery of different low carbon infrastructure projects and, looks at the co-benefits that councils can bring in health, job creation and a reduction in carbon emissions.

It does this through an analysis of how greater investment, clarity of policy and responsibilities and, knowledge and data for councils can enable them to go further and faster to achieve net zero. Examples of good practice by a range of councils are also captured, including where they are already working positively with government to deliver some low carbon infrastructure projects.

If we are to achieve the goals of the Paris Agreement and meet the UK’s net zero target by 2050, decarbonisation must happen in every place across the country and this will require local leadership. I hope you enjoy reading this report.

Councillor David Renard, Chair of the LGA’s Economy, Environment, Housing and Transport Board and Leader of Swindon Borough Council.

Executive summary

Councils can unlock significant economic, social and environmental value by delivering low carbon infrastructure.

Unlocking this value requires national government and local government to be partners in meeting the net zero challenge.

This partnership can support the Government’s ambition to be at the forefront of the Green Industrial Revolution, to Level Up and to Build Back Better.

This report sets out a business case for why councils are best-placed to locally deliver projects in three categories of low carbon infrastructure: buildings, transport and energy.

The strategic case

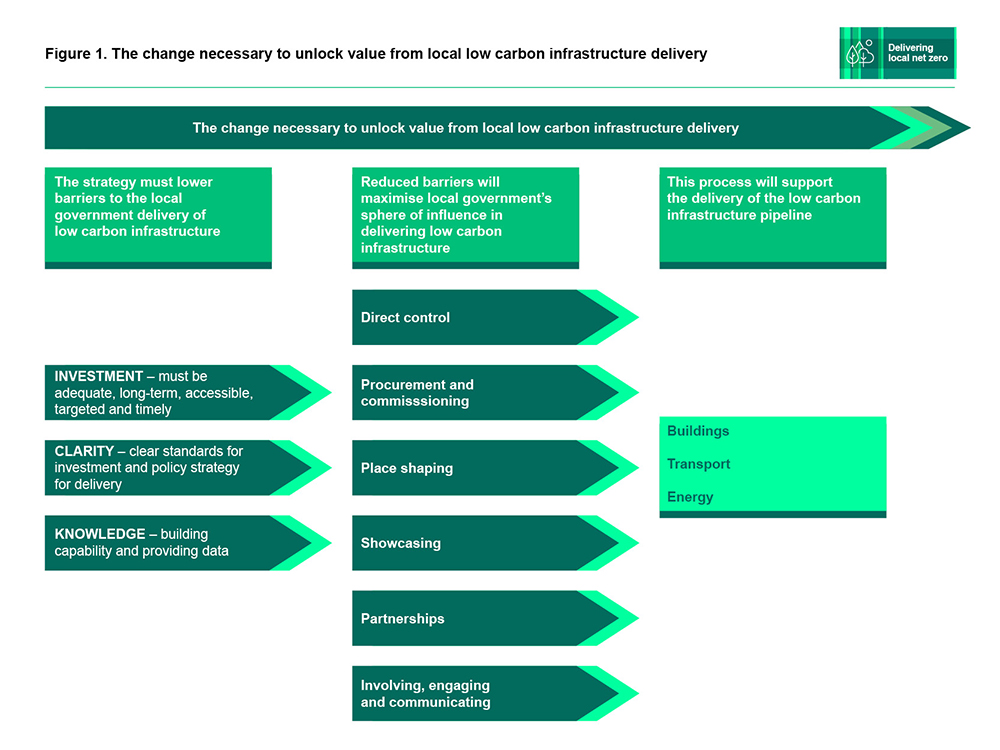

Councils can – and do – control and influence the delivery of low carbon infrastructure using their powers, procurement processes, place-shaping expertise, convening capability and trusted relationship with residents.

There is an opportunity for councils to create more value from locally-delivered low carbon infrastructure. This opportunity can be unlocked by lowering or removing barriers to delivering low carbon infrastructure in three ways:

- A new approach to investment. Longer-term funding to build local government and industry capacity, sufficiency of funding to undertake projects of significant scale and scope, accessibility of funding to all councils, timely funding so as not to deter projects and flexible funding to cover all aspects of local low carbon infrastructure delivery.

- Providing clarity. Unambiguous central government policy positions can provide councils with strategic direction for low-carbon infrastructure delivery.

- Accumulating more knowledge and information. Councils need to develop net zero capability to be able to deliver low carbon infrastructure. This requires resources to hire people into post, either who have experience or who can gain it. There also needs to be a stronger evidence-base, with high-quality data in particular being important to being able to successfully deliver net zero.

The economic case

With a new approach to investment, more clarity and greater knowledge and information, councils will be able to more effectively deliver low carbon infrastructure. This improved effectiveness will unlock value and co-benefits. Our illustrative modelling on the topics of buildings and transport looked at three scenarios:

- Scenario one – the status quo, where low carbon infrastructure delivery related to buildings and transport remains at historic levels in future years. This provides the baseline against which the two other scenarios are assessed.

- Scenario two – intermediate action, where investment is increased to partially meet the balanced net zero pathway for transport set out by the Climate Change Commission (CCC) and, in the case of low carbon buildings, partially meeting the Government’s target to end fuel poverty by 2030. It is assumed that the barriers to delivery of low carbon infrastructure will be partially addressed.

- Scenario three – comprehensive action, where investment is increased to fully meet the balanced net zero pathway for transport set out by the CCC and, in the case of low carbon buildings, fully meet the Government’s target to end fuel poverty by 2030. It is assumed that the barriers to delivery of low carbon infrastructure will be fully addressed.

Buildings – councils retrofitting homes

Through a combination of local knowledge, experience, trusted status, relationships with residents and the ability to forge local partnerships, councils are best-placed to deliver programmes to decarbonise England’s building stock.

Specifically, councils can deliver retrofit programmes for public buildings, local authority-owned housing and fuel poor households more broadly. This retrofit includes energy efficiency measures and installing low-carbon heat sources.

These programmes can create economic, social and environmental value by building and deepening local supply chains (thereby 'pump-priming' the market), supporting jobs, reducing NHS costs and lowering greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions.

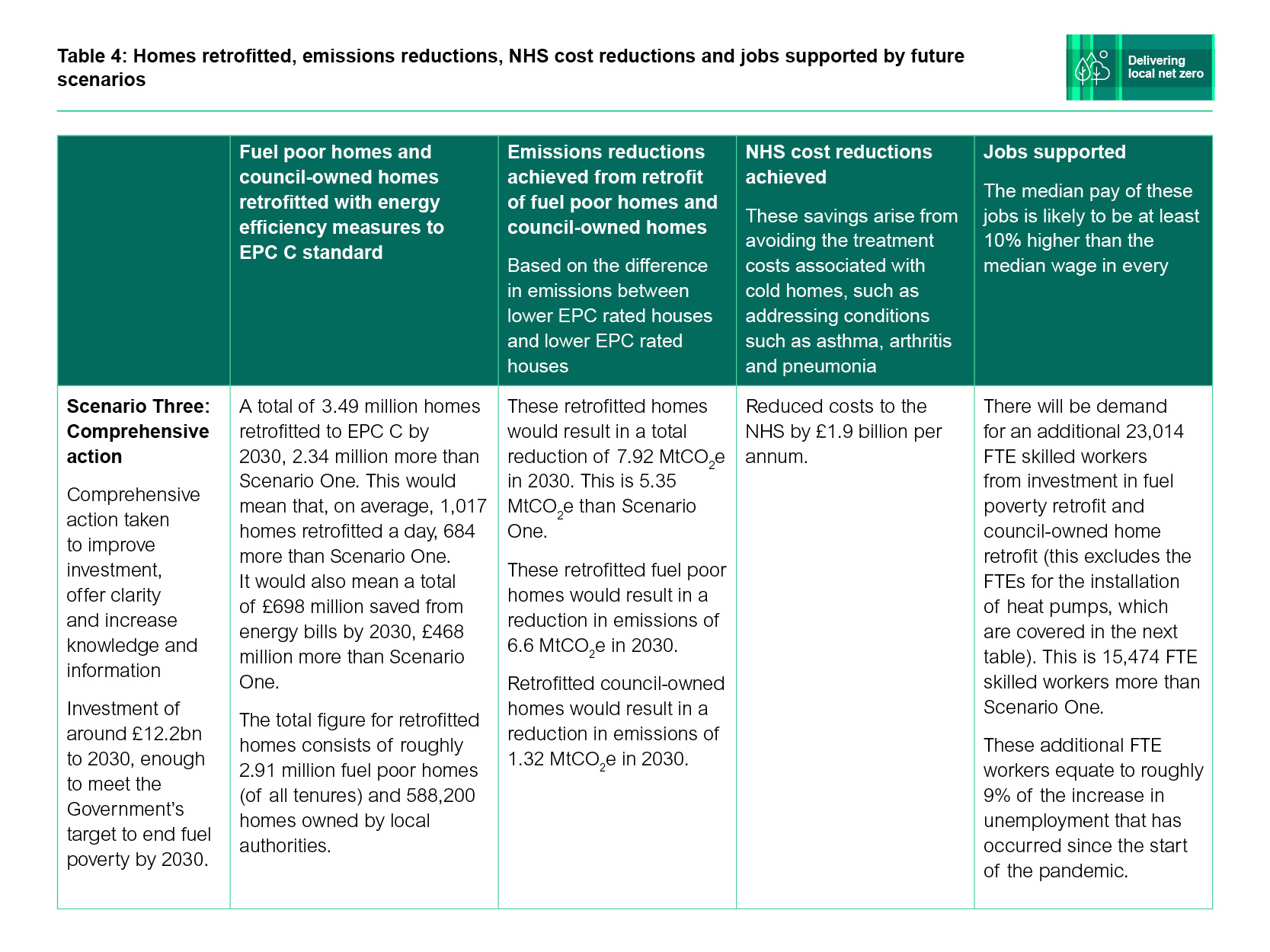

With the comprehensive action on increasing investment, a new approach to investment, central government providing policy clarity, and more knowledge and information accumulated by councils, the following value can be created:

- A total of 3.49 million homes retrofitted to Energy Performance Certificate (EPC) C by 2030, 2.34 million more than the status quo.

- This would mean, on average, 1,017 homes retrofitted a day, 684 more than the status quo.

- It would also mean a total of £698 million saved from energy bills by 2030, £468 million more than the status quo.

- These retrofitted homes would result in a total reduction of 7.92 MtCO2e in 2030. This is 5.35 MtCO2e less than the status quo.

- Reduced costs to the NHS by £1.9 billion per annum

- There will be demand for an additional 23,014 full-time equivalent (FTE) skilled workers from investment in fuel poverty retrofit and local authority-owned home retrofit. This is 15,474 FTE skilled workers more than the status quo.

- These additional FTE workers equate to roughly 9 per cent of the increase in unemployment that has occurred since the start of the pandemic.

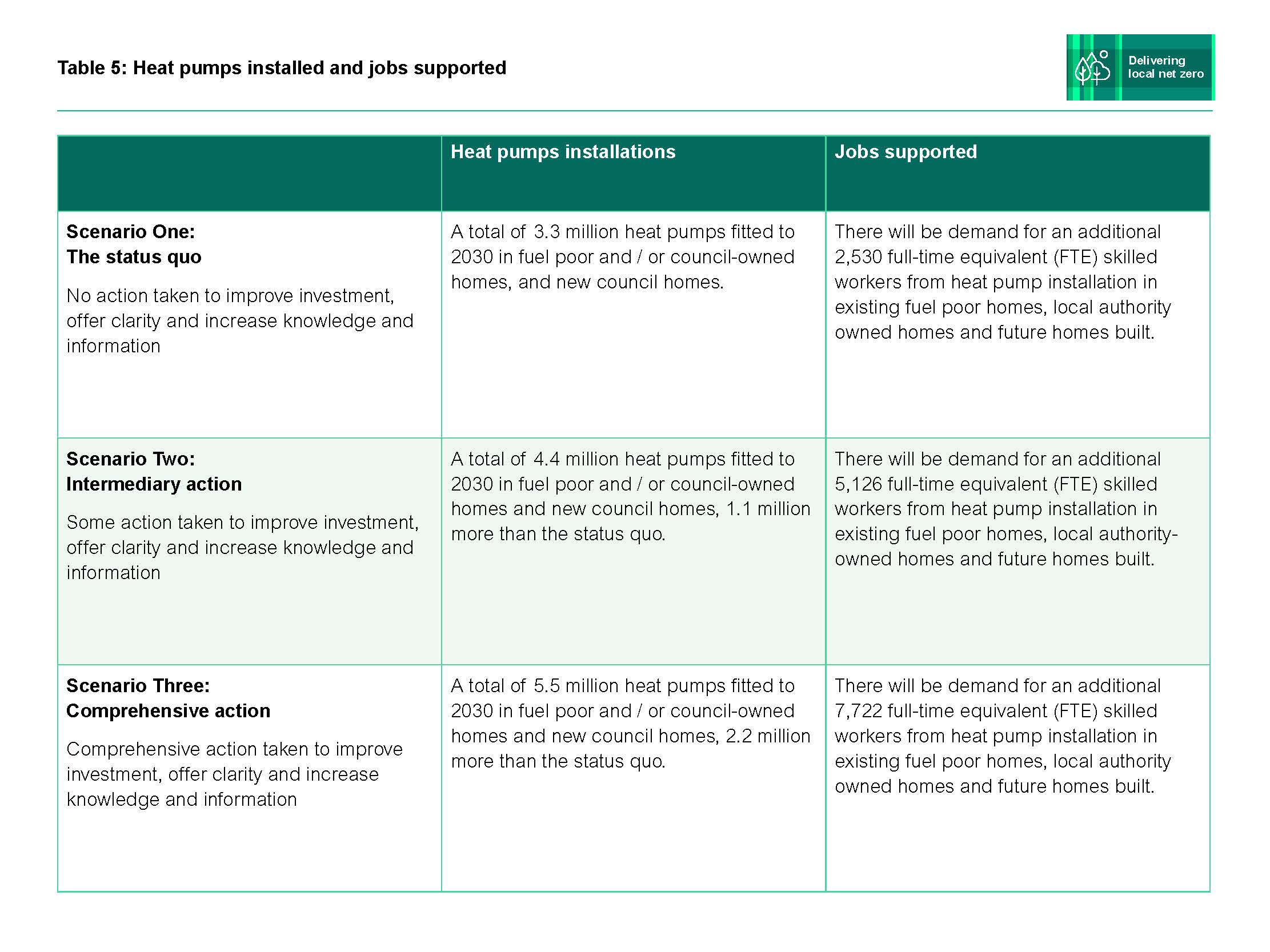

- A total of 5.5 million heat pumps fitted to 2030 in fuel poor and / or council-owned homes and new council homes, 2.2 million more than the status quo.

- There will be demand for an additional 7,722 FTE skilled workers from heat pump installation in existing fuel poor homes, council-owned homes and future homes built.

Transport – councils delivering the infrastructure for modal shift

Councils are best-placed to deliver the infrastructure that will reduce GHG emissions from transport. Through transport plans and local plans, local authorities have the powers to design and deliver a vision for local infrastructure that will enable the switch to low carbon journeys. This council-led infrastructure will unlock value by reducing carbon emissions.

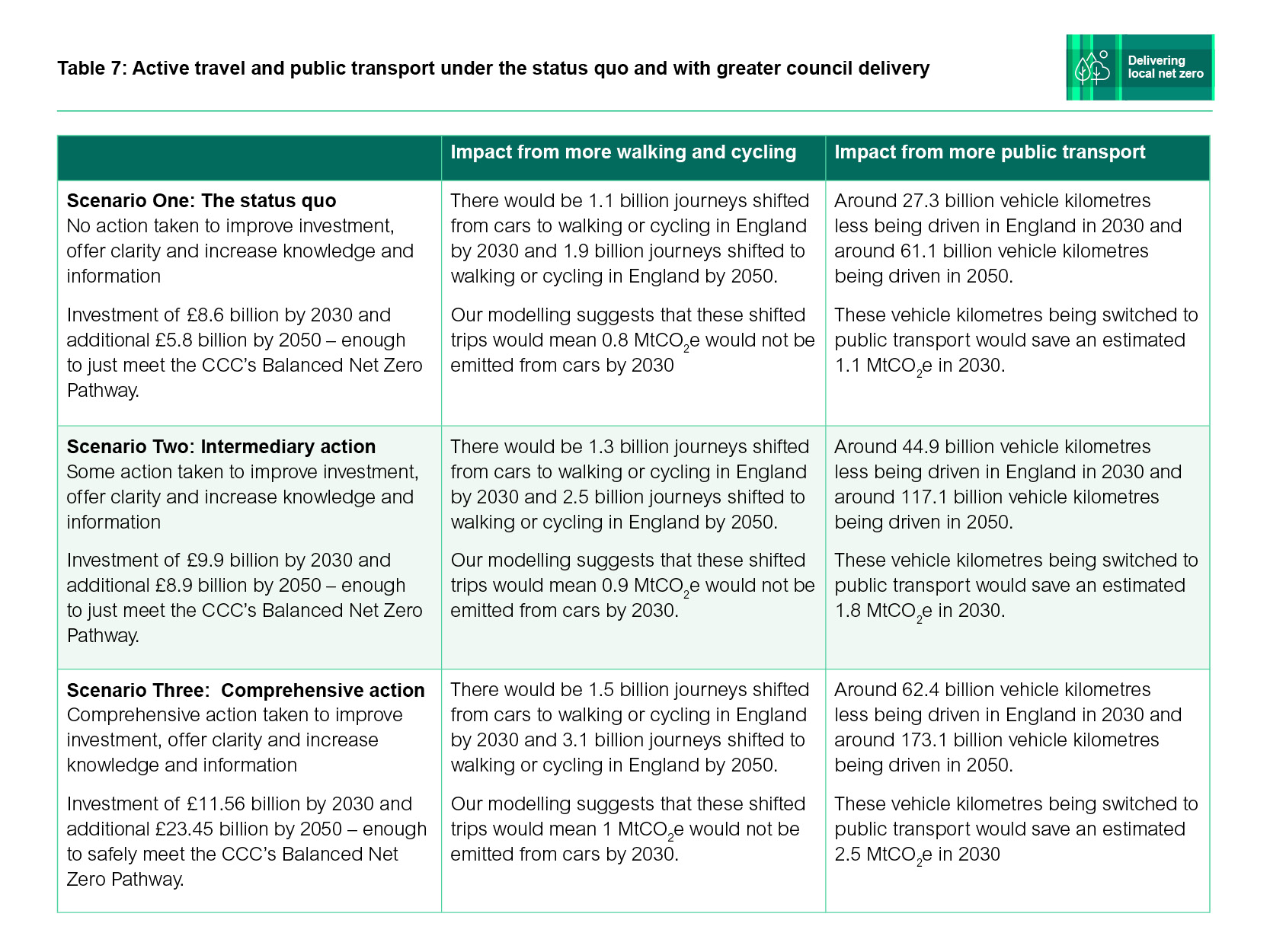

With the comprehensive action on increasing investment, a new approach to investment, central government providing policy clarity, and more knowledge and information accumulated by councils, the following value can be created:

- Investment of £11.56 billion by 2030 and an additional £23.45 billion by 2050 – enough to safely meet the CCC’s Balanced Net Zero Pathway – would mean 1.5 billion journeys shifted from cars to walking or cycling in England by 2030 and 3.1 billion journeys shifted to walking or cycling in England by 2050.

- Our modelling suggests that these shifted trips would mean 1 MtCO₂e would not be emitted from cars by 2030.Enabling switches to public transport away from cars would result in around 62.4 billion vehicle kilometres less being driven in England in 2030 and around 173.1 billion vehicle kilometres less being driven in 2050.

- These vehicle km being switched to public transport would save an estimated 2.5 MtCO₂e in 2030.

Energy – councils making clean energy projects happen

Councils are integral to the delivery of clean energy projects through the planning system, convening relevant local stakeholders, and offering support and information for local community groups to undertake energy projects.

For councils to continue to have a major role in the delivery of renewable energy and heat networks, resource and capability is key. More clean energy infrastructure projects will be needed in the coming decades if net zero is to be met.

With the comprehensive action on increasing investment, a new approach to investment, central government providing policy clarity, and more knowledge and information accumulated by councils, councils can continue to be instrumental in the delivery of clean infrastructure projects, of which they have a strong record:

Introduction

Councils as Government’s partners to deliver low carbon infrastructure

Councils are committed to achieving net zero through both adaptation and mitigation. They are developing capability on environmental issues, setting ambitious local climate targets and implementing innovative, emissions-reducing policies. They are delivering economic, social and environmental value in the process.

This report presents a business case, arguing that councils can create even greater economic, social and environmental value from the local delivery of low carbon infrastructure.

This greater value would bring co-benefits – job creation, business creation, innovation and a healthier population. It would also support the Government’s ambition to be at the forefront of the Green Industrial Revolution, to Level-Up and to Build Back Better.

Unlocking this value requires a change to the status quo. Local government and national Government must strengthen their partnership in the delivery of low carbon infrastructure if the scale of the net zero challenge is to be met.

The content of the report was informed by a literature review, semi-structured interviews with local government officials, senior councillors, representative bodies, Whitehall officials and an illustrative modelling and quantitative analysis.

Defining low carbon infrastructure

The types of infrastructure that will contribute to net zero are many and varied, from residential retrofits to renewable energy projects, and from Electrical Vehicle (EV) charging points to reforested land.

Some of this infrastructure directly contributes to reducing GHG emissions – a wind turbine producing zero-emissions energy, for instance. Some of the infrastructure indirectly contributes, such as a new cycle lane that enables commuters to leave their car at home.

This report focuses on three categories of low carbon infrastructure – buildings, transport and energy – that will play a significant role in the transition to net zero, and that councils can have an instrumental role in delivering.

The rest of this report

The rest of this report is structured as follows:

- An outline business case. Describing the strategic case and the economic case for why a strengthened partnership between local and national government can deliver greater value from the delivery of low carbon infrastructure.

- Key statistics. Summarising the key statistics from the analysis undertaken.

Business case

How councils can create more value from the local delivery of low carbon infrastructure

The business case analysis has two parts:

- The strategic case. Explaining why councils are important to delivering low carbon infrastructure projects through their functions and responsibilities.

- The economic case. Illustrating how councils can create more economic, social and environmental value in the delivery low carbon infrastructure.

The analysis in this chapter is based upon HM Treasury’s guidance for how to develop business cases for new spending proposals.

The strategic case

The strategic context

Following an audit of low carbon infrastructure types, our research identified three categories of low carbon infrastructure that councils can significantly influence the delivery of:[F1]

- Buildings. The existing and future stock of residential, commercial and public buildings that account for a large proportion of the UK’s carbon emissions.

- Transport. The physical infrastructure that will enable a change in the transport we use and how we use it.

- Energy. The many new and emerging methods of generating cleaner energy and reducing energy consumption.

A key point is that while councils can significantly influence the delivery of these types of infrastructure, they will need the right support and partnerships with central government and the private sector.

Central Government has a range of policies – targets, funding pots and regulatory change – to support the local delivery of low carbon infrastructure in each of the above categories. Moreover, national government can be supportive and enabling of local government in making the low-carbon transition, with local energy strategies, local energy hubs and the national bus strategy all being referenced in this regard during our research interviews.

Private businesses will also have a role, be it in decarbonising the buildings they occupy and their production processes, developing low-carbon supply chains through their purchasing, nudging and encouraging employees and customers to make low-carbon decisions, as well as innovating in low-carbon goods and services.[1]The private sector will be important for providing the funding for low-carbon infrastructure at a local level, with investors being a source of long-term capital that can complement public funds.[2] A good example is the Heat Networks Investment Project, which is being used to leverage around £1billion of private investment to support the commercialisation and construction of heat networks.[3]

The large majority of councils have plans to deliver low carbon infrastructure (and many councils have looked at their own estates and assets as a starting point to do so). Working with central government and private business, councils – as the CCC has set out – have the ability to exert significant control and influence over the delivery of local low carbon initiatives (described below in Table One).[4]

|

Council area of control and influence |

Examples of action |

|---|---|

|

Direct control Energy used in council owned buildings and estates, car fleets and electricity purchases, tree planting on council land. |

Leeds City Council currently has one of the largest local authority fleets with 380 EVs, 45 of which are being used by local businesses as part of an EV Trials Scheme to encourage wider uptake. After taking part in the Trials scheme, 50 per cent of organisations have told the council that they are now considering switching to zero emission vehicles.[6] North Somerset Council plans to rewild as much of its land as possible, following a public consultation held in 2019/20, which includes allowing natural succession to take place on some grassy areas.[7] |

|

Procurement and commissioning Large contracts and purchases for external services and resources in waste collection, construction, social services and facilities management. |

Cornwall Council was the first council in the UK to successfully commission a council-owned solar farm which produces eight megawatts of solar PV - enough to provide energy for 1500 homes.[8] Nottingham City Council have pledged in their Neutral Action Plan to work with businesses and citizens to use procurement approaches that encourage suppliers to report on their operational emissions. They will look to establish a citywide energy and carbon ratings scheme for businesses, encouraging transparency in procurement.[9] |

|

Place shaping Use of statutory powers and duties that considers the interconnectivity of planning, land use, buildings, transport, and sustainable development. |

Bury Council ran a Local Area Energy Planning pilot in collaboration with Energy Systems Catapult. This was an example of powers being utilised by local planning authorities. The study found that decarbonisation options were highly specific to local conditions, existing buildings and infrastructure.[10] Implementing heat networks and converting gas boilers to heat pumps are examples of infrastructures that require a holistic approach and spatial planning is one of the biggest opportunities local authorities have to deliver net zero.[11] |

|

Showcasing Demonstrating climate awareness by implementing innovative technologies and processes at the top, rewarding good practice and scaling up successful measures where appropriate. |

Lancaster City Council declared a Climate Emergency in January 2019, at which point the Local Plan had been submitted and it was not possible to be significantly amended. The Local Plan was adopted in July 2020, and the council immediately entered a Climate Emergency partial review to ensure that climate change mitigation and adaptation become fundamental to placemaking in the district. Following a scoping consultation, 32 policies were highlighted for review, improvement, and strengthening. The policies encompass the themes of sustainable design, energy efficiency and renewable energy, sustainable transport, green and blue infrastructure, heritage, and water management. [12] |

|

Partnerships Coordinating thinking across business, academic, public, community and voluntary sectors. |

Essex County Council plan to develop an Essex Waste Partnership which will fully engage with producers, industry and research bodies to support a circular economy. This will involve setting up a network of community-based reuse and repair hubs by 2024 to reduce wasteful consumption and encourage upcycling of possessions.[13] Plymouth City Council is installing a network of underground pipes that has given resource to developers, architects and businesses to fit necessary units.[14] |

|

Involving, engaging and communicating Using local communications to provide information, request feedback and consult residents, maximising engagement and involvement.

|

The London Waste and Recycling Board created the Advance London programme of investment and free business support for London SMEs that have a circular economy business model or that want to transition to a circular economy business model, contributing to the Mayor’s desire to move London towards becoming a zero waste city.[15] |

The case for change

While councils across the country are delivering local low carbon infrastructure, central government can work with local authorities to reduce or remove barriers to delivering low carbon infrastructure under three categories, set out in Table Two below.

|

Theme |

Description |

|---|---|

|

Investment |

|

|

Clarity |

|

|

Knowledge and information |

|

What change will look like

The economic case

The strategic case set out in the previous chapter explained the opportunity for councils to unlock greater economic, social and environmental value from the delivery of low carbon infrastructure.

The economic case in this chapter sets out the results of an illustrative modelling analysis to quantify this value and the co-benefits for the infrastructure categories of buildings, transport and energy.

For each of these infrastructure categories, the following is described:

- why the infrastructure is relevant to net zero

- why councils are best-placed to deliver the infrastructure

- the potential value that this infrastructure delivery could bring

- a case study of how local authorities are delivering the infrastructure now.

Some of the modelling results come with a high degree of uncertainty. Hence, where appropriate, we have conducted analysis with a range of assumptions to demonstrate where there is a range of options.

For the topics of buildings and transport our illustrative analysis looked at three scenarios:

- Scenario one – the status quo, where low carbon infrastructure delivery related to buildings and transport remains at historic levels in future years. This provides the baseline against which the two other scenarios are assessed.

- Scenario two – intermediate action, where investment is increased to partially meet the balanced net zero pathway set out by the CCC and, in the case of low carbon buildings, partially meeting the Government’s target to end fuel poverty by 2030. It is assumed that the barriers to delivery of low carbon infrastructure will be partially addressed.

- Scenario three – comprehensive action, where investment is increased to fully meet the balanced net zero pathway set out by the CCC and, in the case of low carbon buildings, fully meet the Government’s target to end fuel poverty by 2030. It is assumed that the barriers to delivery of low carbon infrastructure will be fully addressed.

The investment needed to fund the net zero transition will come from a combination of public, private and household sources. Hence, the figures for the investment needed to meet different scenarios do not specify the investment source. However, government has a crucial role in mobilising private finance and some types of low carbon infrastructure will rely on public investment more than others (for example, fuel poor households).

A methodology and data sources used for the quantitative exercise can be found in Annex I.

Buildings – councils retrofitting homes

Key points

- Because of their local knowledge, experience, trusted status, relationships with residents and the ability to forge local partnerships, councils are best-placed to deliver programmes to decarbonise England’s building stock.

- Specifically, councils can deliver retrofit programmes for public buildings, council-owned housing and fuel poor households. These programmes would include energy efficiency measures and the installation of low-carbon heat sources.

- These programmes can create economic, social and environmental value by building and deepening local supply chains (thereby 'pump-priming' the market), supporting jobs, reducing NHS costs and lowering GHG emissions.

Background

Our homes, workplaces and publicly-owned properties are responsible for 17 per cent of all UK GHG emissions. The large majority of these emissions are created from burning fossil fuels for heat. [19]

As a result, making current and future buildings more energy efficient and heated from lower carbon sources are important routes to net zero.[20]

The Government is taking action in this regard. Various funding streams have been put in place. Five Local Energy Hubs – to support councils, community groups, businesses and residents to lead energy projects – have been created. A Buildings and Heat Strategy is due to be published.

The scale of the task to decarbonise the country’s buildings, however, is huge. The CCC estimates that the combination of energy efficiency measures and low carbon heating methods required in homes to meet net zero will cost £250 billion by 2050 (funded by a combination of public, commercial and household investment). [21] For context, the investment needed to complete Phase One of HS2 is around a fifth of this figure.[22]

Why councils can deliver more value

Councils are taking action to decarbonise buildings in their areas. They are retrofitting public sector buildings and council-owned housing. They are promoting the benefits of retrofit within their communities and trialling innovative new retrofit approaches. They are building low carbon council houses and using the planning process to implement higher energy efficiency standards than the minimum required by building regulations.[23]

Original research for this report, and a range of existing evidence, provides five reasons why councils are best placed to deliver further programmes to decarbonise buildings:

- Local knowledge. Councils know the state of their local housing stock and the characteristics of their local population. This means councils can tailor retrofit schemes to take account of local factors such as tenure, housing type and deprivation.[24]

- Experience. Councils have been involved in energy efficiency schemes for low-income households for many years, for instance, through referring their residents to energy suppliers as part of the Energy Company Obligation.[25]

- Trust. Vulnerable households can sometimes trust councils more than they trust private companies, some of which are associated with sub-standard work.[26]

- Leadership. If residents are to be mobilised to change behaviour to support net zero then local authorities have a clear role to play in making “national policy locally relevant”.[27]

- Ability to forge local partnerships. Local authorities can act as intermediaries to drive innovative, partnership approaches to retrofit.[28]

Our analysis illustrates the type of value councils can deliver in two areas:

- Retrofit of fuel poor households and council-owned homes. The Government counts a household as 'fuel poor' if its residual income is below the poverty line after accounting for fuel costs, and lives in a home that has an energy efficiency rating below EPC Band C.[29] Council-owned homes are the homes that are rented directly from councils. Some (but not all) council-owned homes are classed as fuel poor.[30]

- Heat pump installation. Part of the Government’s plan to tackle fuel poverty is increasing energy efficiency by installing heat pumps (where appropriate).[31]

Fuel poor households and council-owned housing are occupied by those unlikely to be able to pay for energy efficiency measures. By giving councils the certainty and means to invest in retrofit programmes, local supply chains will be bolstered and 'pump-prime' local retrofit and low-carbon heating markets for the households that are able to pay. These more developed supply chains will support higher quality and lower cost retrofits and installations [32]

A focus on fuel poor and council-owned households

There are an estimated 3.5 million households in England that are either fuel poor and / or owned by councils that require retrofitting to achieve energy efficiency rating EPC C.

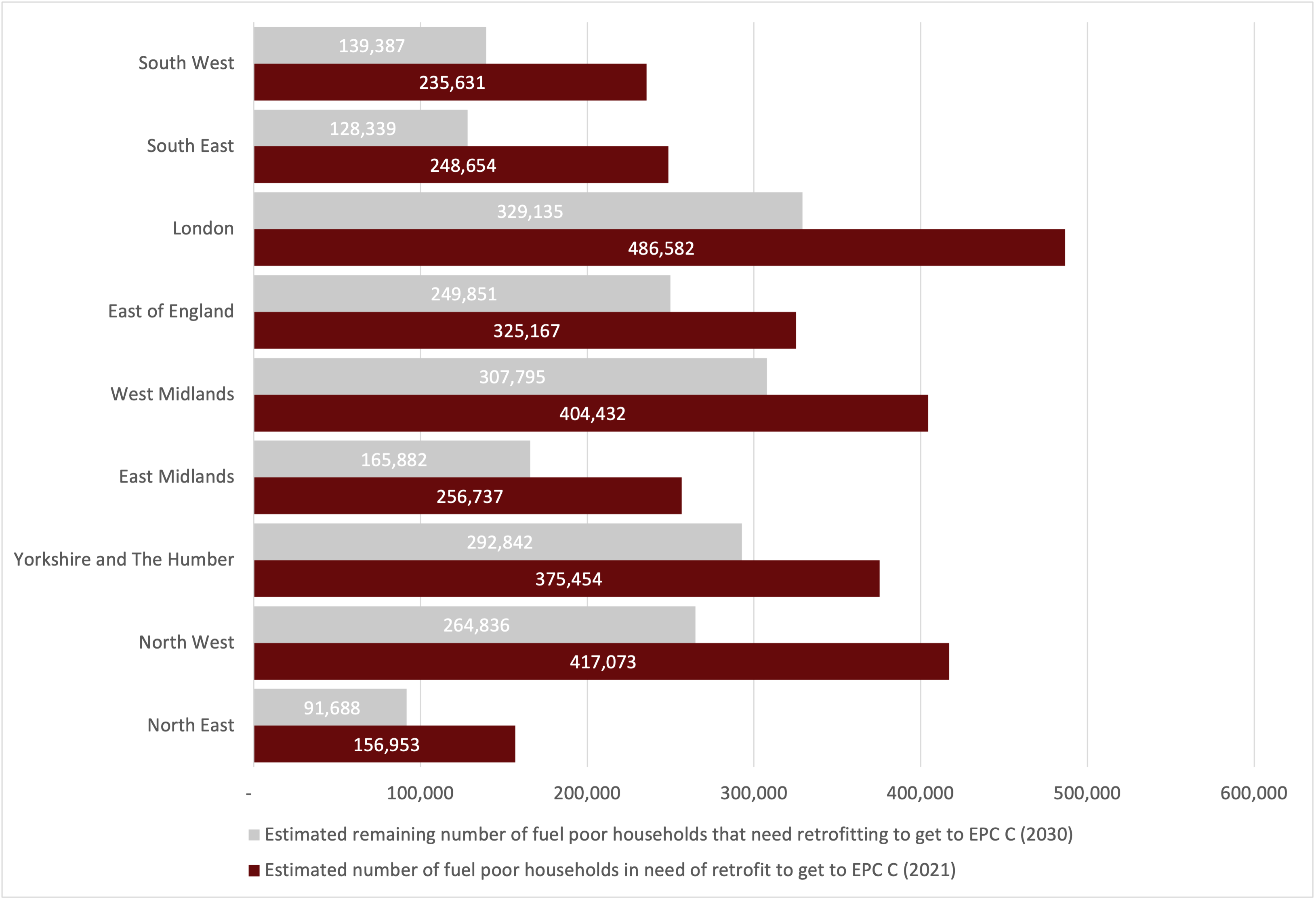

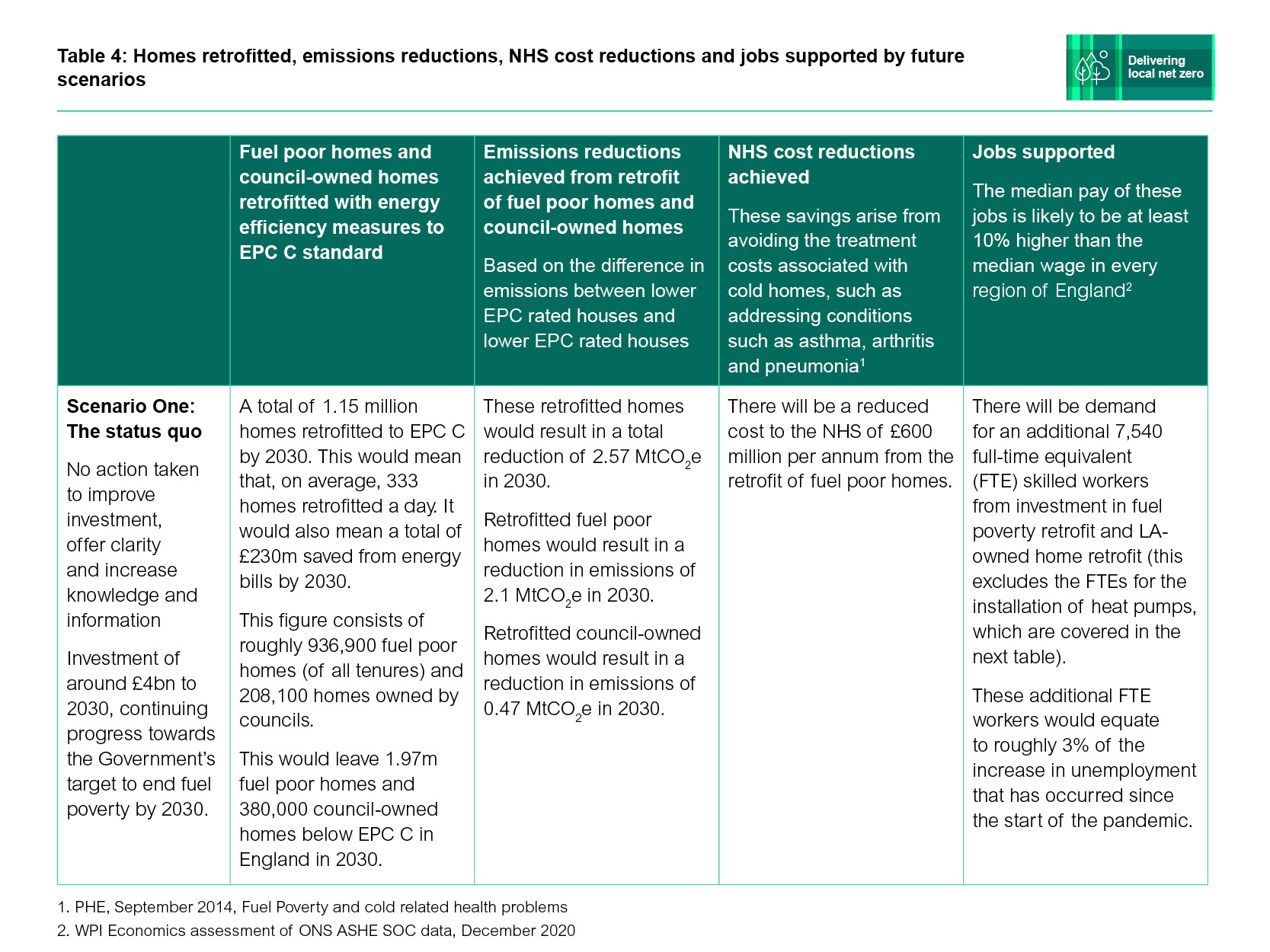

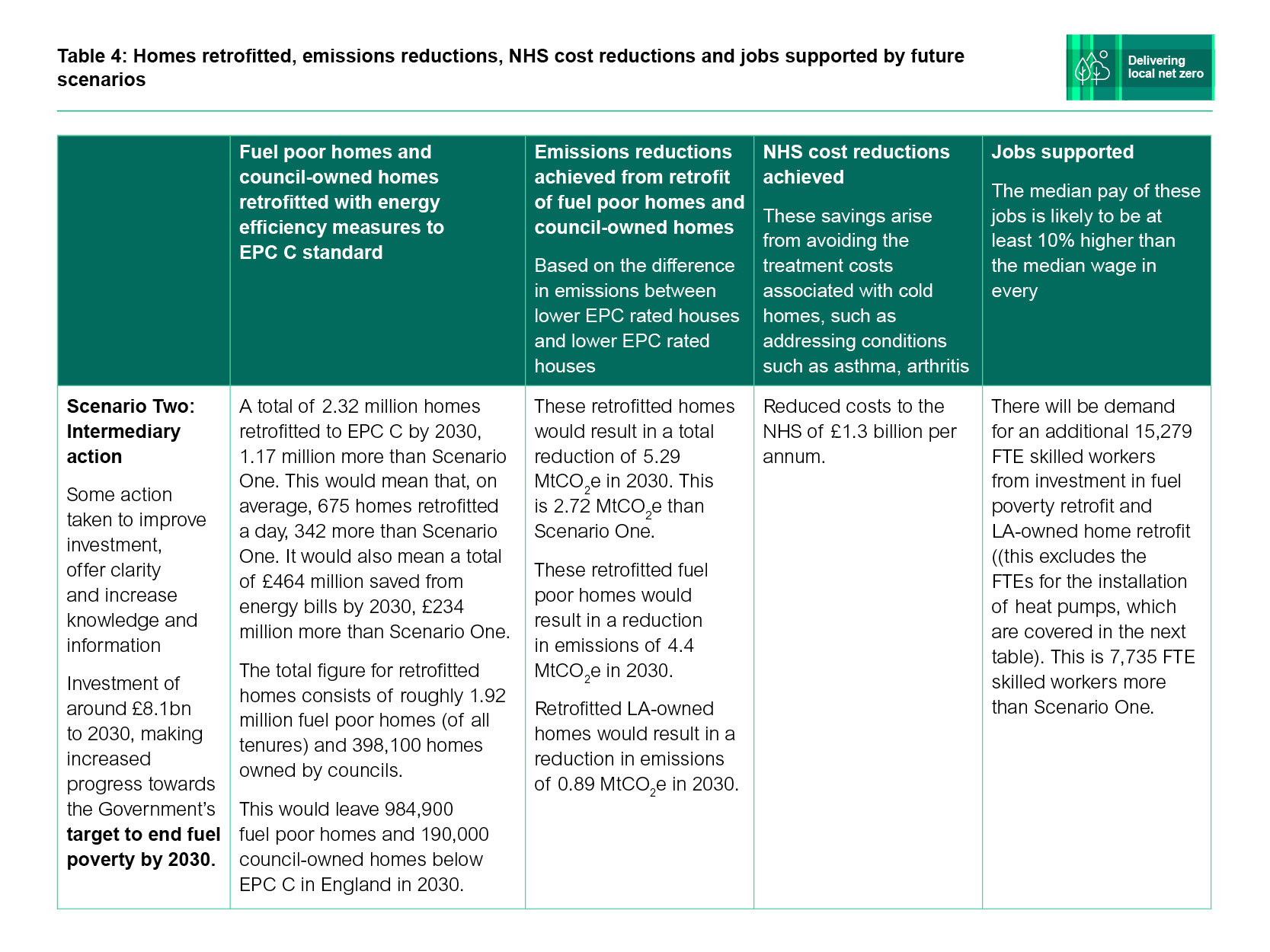

Of this 3.5 million figure, roughly 2.9 million are fuel poor homes (of all tenures, including council-owned housing).[F2] The Government has a statutory fuel poverty target, “to ensure that as many fuel poor homes as is reasonably practicable achieve a minimum energy efficiency rating of Band C, by 2030”.[33] If the rate of reduction in fuel poor households is the same in the 2020s as it was in the 2010s then there will still be 1.97 million households in need of fuel poverty retrofit by 2030. These households will be spread across all regions of England (see Chart One, below). Put another way, without a change of course, only 32 per cent of the required retrofits to meet the Government’s target will have taken place by 2030.

Based on trends of the last ten years, unless Government changes course, there will be 1.97m English households in need of fuel poverty retrofit by the end of the decade.

[F2] This 2.9 million figure is modelled for 2021 (with the latest available data 2019). Households living in EPC A, B or C homes that are unable to afford sufficient energy to keep warm are not included in the Government’s fuel poor households definition. These households will not significantly benefit from further energy efficiency measures. Thus, to ensure the end of fuel poverty on the Government’s definition requires increasing energy efficiency to EPC C in all fuel poor households (where possible). There are two other routes to ending fuel poverty that the Government has much less control over – incomes in fuel poor households could rise, or energy bills could fall (or both).

The remaining 0.6 million of the 3.5 million figure are not fuel poor and are owned by councils.

Council-owned homes – which includes both flats and houses – tend to have higher EPC C ratings, on average, than privately rented flats and homes. Yet it is still estimated that 39 per cent of these homes are below EPC C rating within homes.[34] On current trends, just over a third of these homes (35.3 per cent) will be retrofitted by 2030, leaving 380,000 council-owned homes below EPC C rating.

In our illustrative modelling scenario that assumes comprehensive action (see these scenarios in Table Three), councils would retrofit all 3.5 million fuel poor homes to EPC C and this would create a range of co-benefits in health, job creation and carbon reduction. These are:

- a total of £698 million saved from energy bills by 2030

- a reduction in emissions of 7.9 MtCO2e, roughly 8.7per cent of the total emissions from buildings that were identified by the CCC

- reduced costs to the NHS of £1.9 billion per annum, from avoiding the treatment costs of health issues associated with cold homes

- demand for 23,014 FTE skilled workers from investment in fuel poverty and council-owned retrofit (These additional FTE workers equate to roughly 9 per cent of the increase in unemployment that has occurred since the start of the pandemic)

A focus on heat pumps

Key to making homes more energy efficient is changing how they are heated. The CCC expects the large majority of low carbon heat installations in residential buildings to be heat pumps. However, the market for heat pump installation is very much in its infancy, with rapidly scaled-up supply chains required if heat pumps are to contribute to net zero in the way that is hoped.

Councils can play a role in scaling-up these supply chains and building a thriving market for low-carbon heat through retrofitted installations within fuel poor homes and council-owned homes, and in the future pipeline of new council homes. There will be tens of thousands of new council homes built over the next decade, which have the potential to be built to low carbon standards and using low carbon heat solutions.

Some councils are already installing heat pumps in their council housing stock and in low-income households. There are examples from Warwick, Hambleton and Manchester councils – to name just a few – that are using Green Homes Grant Local Authority Delivery scheme (GHGLAD) to install heat pumps. The CCC has also suggested that ‘pathfinder cities’ can be funded to demonstrate how heat pumps could be deployed at scale.

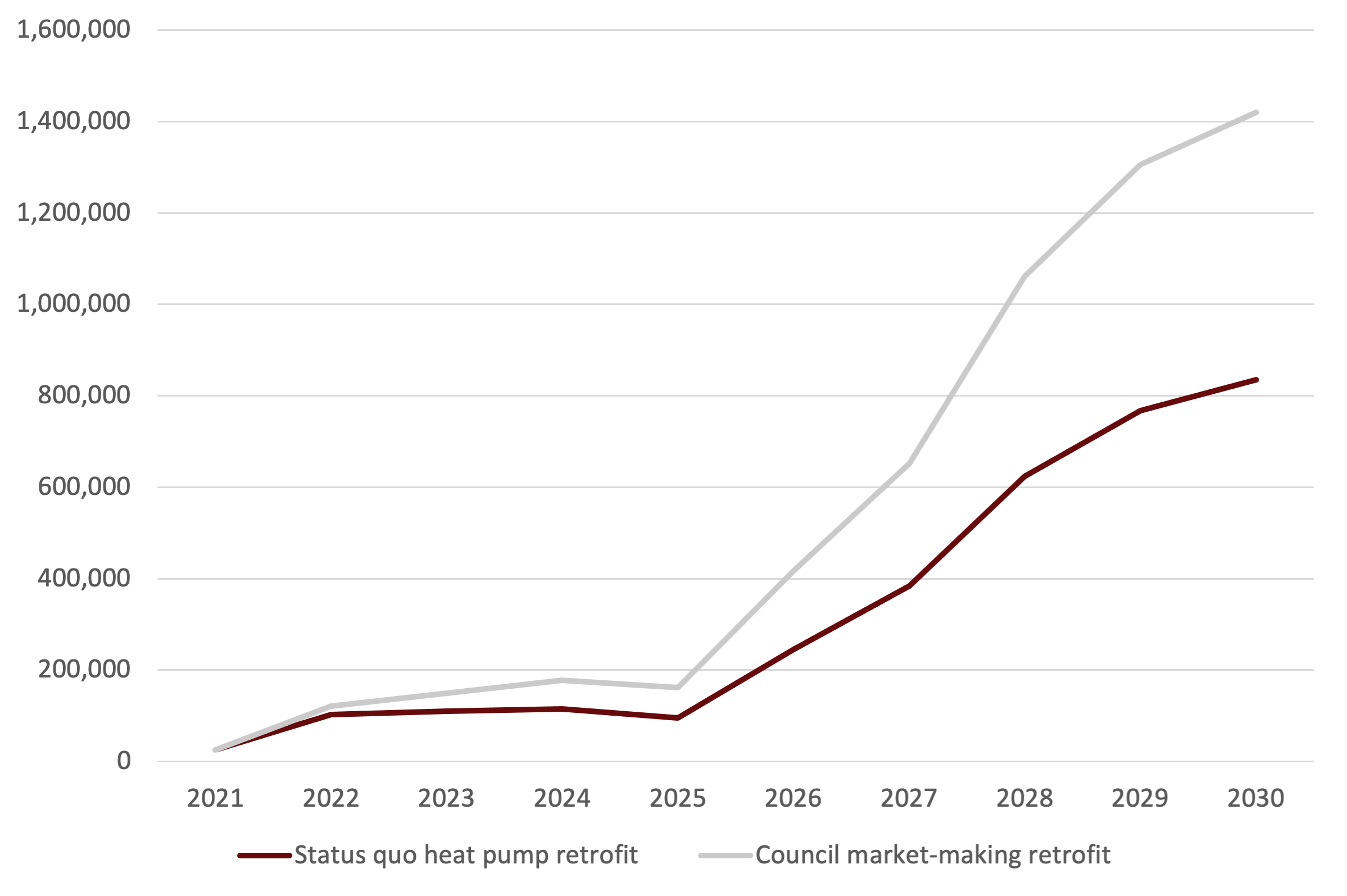

Our illustrative modelling scenario that assumes comprehensive action suggests that if councils were funded to deliver heat pumps in the 3.5 million fuel poor, existing council-owned homes and new council-owned homes (based upon current build rates), the installation numbers of heat pumps over the next decade could be higher (see Chart Two, below). The analysis suggests that this could lead to:

- 585,000 more installations a year by 2030

- a total of 2.2 million more heat pump installations by 2030 than otherwise would be the case

- a total of 7,772 jobs supported.

This would go some way to achieving the government’s target of installing 600,000 heat pumps a year by 2028 as set out in the Energy White Paper.[35]

2.2 million more heat pump could be installed by 2030 if councils were funded to lead heat pump installation programmes in fuel poor homes, local authority owned-homes and new council houses. WPI Economics analysis

Supporting jobs

It is widely accepted that more skilled workers are needed in construction supply chains to retrofit our building stock.[36] As explained above, councils have the potential to support almost 31,000 jobs from the retrofit of fuel-poor and council homes and the installation of heat pumps all over the country. The highest number of skilled workers would be supported in urban areas – Birmingham, Leeds, Sheffield, Manchester and Bradford. The highest relative numbers of additional skilled workers required can be found in areas outside the South East. Table Three sets out the number of jobs supported through retrofit and heat pump installation programmes.

Some areas will require more investment to undertake the measures described above. For instance, the Midlands and North of England require higher investment on a per household basis because there are relatively more fuel poor households in these regions. As a result, our modelling suggests that 54 per cent of all investment into energy efficiency measures in fuel poor households would be needed in the Midlands and North.

| Specialism |

Proportion of jobs |

Total jobs |

|---|---|---|

|

Heating, ventilation and air conditioning (HVAC) specialisms |

10% |

3,089 |

|

Hydrogen boiler conversion |

1% |

214 |

|

Heat pump installation |

25% |

7,722 |

|

Electricals |

9% |

2,714 |

|

Smart metering |

7% |

2,062 |

|

Renewables specialisms |

3% |

870 |

|

Window installation |

5% |

1,400 |

|

General construction training |

15% |

4,721 |

|

TrustMark retrofit other specialisms |

14% |

4,369 |

|

TrustMark retrofit coordinator |

11% |

3,575 |

Table five (tagged PDF): Heat pumps installed and jobs supported

Case study – Hampshire County Council, approach to housing retrofit

The challenge

In order to meet the recommendations set out by the CCC, the UK building stock will need to be completely decarbonised by 2050.[39]

It is estimated to cost £15 billion to retrofit all homes in Hampshire, which will require partnerships across private and public organisations and a spectrum of available job opportunities.

Hampshire County Council first ran a retrofit initiative in 2008 with ‘Insulate Hampshire’. The scheme ran its course due to the end of the ECO funding for it.

The solution

The Hub’s collaboration with Local Enterprise Partnerships has allowed the number and the quality of retrofit projects to be extended across the Greater South East and West regions of England.

The Hub also works through local organisations, which incorporates collective action to purchase and manage energy, working more efficiently and allowing for better value for money.

This model is currently the most viable to address the low income retrofit issue due to the short-term nature of current funding.

The benefits

There has been an increased effort in recent times to address retrofit in existing council stock and commercial buildings, but by reaching the bulk of the domestic market (which isn’t always incentivised by market forces to make energy efficiency changes), Hampshire will be taking the vital next steps to achieving net zero by 2050.

The existing experience and knowledge in retrofitting social housing and estates in the area will be highly transferable and will create the right environment for more ambitious programmes.

It is expected that the Hampshire strategy will increase political legitimacy and citizen engagement which can further increase energy savings, as well as contribute to green recovery and job creation post pandemic.

Transport – councils delivering the infrastructure for modal shift

Key points

-

Councils are best-placed to deliver the infrastructure that will reduce vehicle miles. Through transport plans and local plans, local authorities have the powers to design and deliver a vision for local infrastructure that will enable the switch to low carbon transport.

- This council-led infrastructure will unlock value by generating health benefits and by reducing carbon emissions.

Background

Surface transport was responsible for 113 MtCO2e in 2019, making up 22 per cent of total UK GHG emissions. Fossil-fuelled cars, vans and heavy good vehicles (HGVs) are the biggest contributing factor to these emissions.[40]

There LGA has identified three routes to reducing carbon emissions from surface transport:[41]

- Avoid. Travelling less often and reducing the demand for car travel, for example through car sharing or working from home.

- Shift. Supporting investments in cycling, walking and public transport infrastructure as well as encouraging take up of zero-emissions vehicles.

- Improve. Ensuring that existing vehicles are more efficient, such as through lighter-weight designs.

The Government has set targets related to the emissions-reducing pathways for surface transport. One example is the phasing out of petrol and diesel cars and vans, which requires associated electric vehicle charging infrastructure. Another example is the Government’s aim for half of all journeys in towns and cities to be undertaken by cycling or walking, which will require new cycle paths and a different approach to town planning.

The role of councils is to design and deliver the built environment that will enable more low carbon journeys to take place. They are best-placed to do this because they have decision-making powers for transport planning and public transport, as well as responsibility for parking and development. Ultimately, councils can lead transport decarbonisation by treating local transport as a whole system, understanding how different modes of transportations can interact.

This chapter sets out how councils can create more value from delivering low-carbon transport infrastructure under an approach that offers more investment, clarity and information and knowledge than the status quo.

Why councils can deliver more value

Every local area is home to car owners who can switch some of their journeys to lower-carbon alternatives – such as walking, cycling or public transport – and who will eventually have to buy an electric vehicle.

This switch requires locally-delivered infrastructure. Some local funding is already available for this. For instance, £2 billion of funding for cycle and walking infrastructure has been provided over the next five years.[42] The On-street Residential Chargepoint Scheme (ORCS) also allocated over £6.5 million to English local authorities for EV charging infrastructure in the 2020-21 financial year.[43]

This funding will support active travel and public transport initiatives as an alternative to car use. And where cars are needed, the funding will support the infrastructure to ensure they can be electric.

Our analysis looks at the value of councils in delivering infrastructure to enable the switch between public transport and active travel. These are described below, along with a brief note on EV charging infrastructure. Some of the economic and social value is set out in Table Eight, which follows these sections.

Public transport

Councils have significant influence over public transport. They can build partnerships with neighbouring councils, different tiers of government, public transport operators and different sectors. These relationships can help to deliver the fifth commitment outlined in the Government’s Transport Decarbonisation Plan – embedding transport decarbonisation principles in spatial planning and across transport policymaking. This can improve land use at the margin by forbidding new development that is car-dependent and by encouraging residential living around urban centres to reduce road transport carbon emissions[44]. Councils can also help to deliver zero-emissions transportations options, particularly clean buses. They can use data on local travel methods to increase knowledge and understanding about how public transportation systems should be altered and amended.[45]

Councils need investment, clarity and knowledge and information to do this. With comprehensive action to provide this, our analysis suggests that enabling switches to public transport away from cars will result in approximately 62.4 billion vehicle kilometres less being driven in England in 2030 and around 173.1 billion vehicle kilometres less being driven in 2050 (see table six, below).

|

Region |

2030 |

2050 |

|---|---|---|

|

England |

62.5 |

173.1 |

|

North East |

2.9 |

7.4 |

|

North West |

8.0 |

22.2 |

|

Yorkshire and The Humber |

6.8 |

20.3 |

|

East Midlands |

6.1 |

18.4 |

|

West Midlands |

6.6 |

17.9 |

|

South East |

10.1 |

25.5 |

|

South West |

7.7 |

22.2 |

|

East of England |

7.8 |

21.8 |

|

London |

6.4 |

18.7 |

Active travel

The investment previously made available to councils to introduce walking and cycling schemes is a good case study for fragmented local authority funding. Between 2016/17 – 20/21 funding for such schemes came from 16 different sources.

The Department for Transport’s own assessment of this investment was that it was inadequate, supporting only around 40 per cent of the gap towards the Government’s target of doubling cycling by 2025.[46]

While the Government has made more funding available, its plan for decarbonising transport also suggests that the investment is insufficient to realise the potential of walking and cycling. The plan includes forecast scenarios for how active travel journeys could increase for a given increase in investment. The footnotes explain that many more walking and cycling journeys can take place if spending per person on active travel goes above levels of other European nations and that the cost-effectiveness of cycle spending reaches Dutch levels. While comparable statistics are hard to come by, the average annual spend per person on walking and cycling is around £7.65 per head in England compared with an average annual spend of around £25.60 per head in the Netherlands.[47]

With the right investment, there is the potential for 1.5 billion journeys shifted from cars to walking or cycling in England by 2030 and 3.1 billion journeys shifted to walking or cycling in England by 2050. WPI Economics analysis

Councils are the only route to allocate spending on these schemes and are therefore the only route to greater cost-effectiveness. Our modelling suggests that with much greater investment there would be 1.5 billion journeys shifted from cars to walking or cycling in England by 2030 and 3.1 billion journeys shifted to walking or cycling in England by 2050.[48]

This value is summarised in the below table.

EV charging infrastructure

The CCC’s expectation is that around 260,000-480,000 public chargers will be required for electric vehicles by 2040. Based on current estimates of the cost of installation of a charging point, this will cost between £1.8 billion and £3.4 billion.

Councils are able to influence the delivery of EV charging points through their local plans.[49] Not all of these 260,000-480,000 public chargers will need to be on council-owned land (or will require council backing to install if not on council owned land). Nevertheless, the chargers that do require some council intervention can only be effectively supported if schemes like ORCS are user friendly and attractive for councils to use.

Flexibility in funding is key as there are differences within and across places for EV charging need. Only councils can make sense of where funds invested in charging infrastructure can support switch to EV.

Case study – Transport for Greater Manchester

Transport for Greater Manchester is the local government body responsible for delivering Greater Manchester’s transport strategy and commitments. It combines transport functions of a local authority with strategic decisions made at a regional level.

The challenge

Transport currently accounts for 30 per cent of carbon emissions in the area and of these, 95 per cent are from road vehicles.[50]

Road transport in particular has a seriously detrimental impact on air quality and particulate emissions is estimated to cause at least 1000 deaths each year in Greater Manchester.

Creating a joint up travel system that encourages walking and cycling activity will also improve access to healthier lifestyles, reducing the burden on the NHS.

The solution

Franchising powers were reintroduced in Greater Manchester in 2021, which is the first arrangement outside of London.

Control of day-to-day powers and devolution has allowed for greater accountability and for a stronger collective effort in which to tackle transport challenges.

Greater Manchester Council were prepared to stake significant resources into a fund in return for greater certainty over a longer period and for a removal of ring-fences so that money can be managed in one fund. This led to the creation of the Greater Manchester Transport Fund which guarantees predictability of funds.[51]

The benefits

Under this structure, Transport for Greater Manchester can handle businesses cases instead of central government, which can increase turnaround time and the number of projects being processed at any one time.

This has led to the integration and actioning of a variety of projects including but not limited to: bus franchising, extending the Metrolink, developing the bee network, bike hire scheme and the EV charging network.

Transport for Greater Manchester have reallocated resources to increase the capability to handle the volume of business case planned and a critical friend approach has been introduced to assist in more 'first pass' approvals.[52]

Energy – councils making local clean energy projects happen

Key points

- Councils are integral to the delivery of clean energy projects through the planning system, convening relevant local stakeholders, and offering support and information for local community groups to undertake energy projects.

- For councils to continue to have a major role in the delivery of renewable energy and heat networks, resource and capability is key. More clean energy infrastructure projects will be needed in the coming decades if net zero is to be met.

Background

An increase in clean energy production is crucial to the Government achieving its climate goals. For instance, the CCC estimates that to stay on track for net zero, the emissions intensity of generating electricity needs to drop from around 200 gCO2/kWh today to around 10 gCO2kWh in 2035.[53]

Understanding local energy needs – such as the increasing demand for electricity from electric vehicles and heat pumps – will be key to increasing cleaner energy production. This has been described as taking a 'whole systems' approach. The Energy Systems Catapult (ESC) has developed a framework for this approach called Local Area Energy Planning (LAEP). It involves gathering and assessing technical and non-technical evidence, the close coordination of different stakeholders, including local and national government, network operators, energy suppliers, local communities and businesses, and appropriate governance and delivery structures.[54]

LAEP incorporates different facets of decarbonisation, including that of buildings and transport (subjects discussed in the previous two chapters). It also incorporates the subjects of renewable energy generation and district heating, which are discussed below.

Why councils can deliver more value

Every council can encourage the development of clean energy infrastructure. They can bring relevant local partners together to develop plans for the future of local energy, can influence clean energy infrastructure implementation with planning policy, and offer support for local people and community energy organisations to undertake energy projects.

The available data on clean energy infrastructure and how it relates to councils is not as comprehensive as the data related to buildings and transport, meaning that a scenario analysis cannot be undertaken with the same level of detail. However, it is possible to demonstrate how councils play an instrumental role in the delivery of renewables and district heating projects, and why that role will become more important in future years.

Renewables

One example of councils’ role in the delivery of renewable energy is the installation of solar panels. Firstly, councils can lead schemes to install solar panels on public properties. For instance, Oldham Council recently completed a successful pilot that included setting-up a community-owned co-op to installing solar PV on schools and community buildings.[55] Secondly, councils can raise awareness and reduce costs for residents wanting to install solar energy systems. For instance, the Waltham Forest 'Solar Together' scheme encouraged group buying of solar infrastructure for residential properties and gave residents confidence in their purchase by pointing towards vetted installers.[56]

Another example of the role of councils in the delivery of renewable energy is through planning consent. Previous research has highlighted how local planning authorities will provide support to neighbourhood planning groups, including mapping, technical support and support with policy writing. As a practical case study of the importance of council planning departments, a business that installed an onshore wind turbine in Bristol referenced how planning authorities were integral to its development.[57]

There is data that shows the importance of panning departments to renewable energy:

- Over the last ten years, English councils have granted planning permission for 5.5 GW of large onshore wind, offshore wind, energy from waste and solar PV installations.

District heating

The CCC expects around a fifth of heat for buildings to be distributed via heat networks by 2050 and that supply chains need to be quickly scaled-up.[58] The Association of Decentralised Energy estimates that the growth in heat networks could contribute to creating 46,400 to 63,400 new jobs annually during the peak period of heat network installation.[59]

Councils are integral to developing heat network infrastructure. They are best-placed to understand local options for developing heat networks (of which there are numerous types, suited to varied circumstances).

To do this, however, councils need resource and capability to deliver heat network projects.

This is something that has been recognised by the Government in establishing the Heat Networks Delivery Unit (HNDU) in 2013, to help local authorities overcome the challenges in delivering heat networks.[60] Further Government action has come through the Heat Networks Investment Project (HNIP), created to provide £320 million of capital investment to ensure that heat networks get built.[61]

The HNDU and the HNIP will need to continue to be funded well for councils to deliver more via heat networks.

Case study – West of England Combined Authority, South West Energy Hub

The South West Energy hub programme, hosted by the West of England Combined Authority and BEIS, works across the South West region to identify, develop and implement low carbon energy projects. The types of energy projects supported range from home energy retrofitting to street lighting replacement, and from low carbon electricity and heat generation to energy supply for low carbon vehicles.[62]

The challenge

The South West has an abundance of renewable energy resources, including the best wind resource in Western Europe, the best solar resource in the mainland UK and the best geothermal resource in the UK.

However, currently the region is not widely benefitting from these resources and imports almost 88 per cent of its energy, costing £9 billion.[63]

The South West Energy hub is therefore well placed to prime the industry to attract investment and scale of local energy projects.

The solution

The hub provides community support in the form of the Rural Community Energy Fund.

The hub is well represented with representatives made up from the BEIS Local Energy team and each of the seven South West LEP regions.

The management structure ensures that the benefits of the hub are spread evenly across the South West with project managers located in each of the greater sub-regions.

This system ensures that local institutions are connected and best practice is communicated across the hub regions.

The benefits

The hub is well placed to support small scale projects, that central government cannot access as easily.

It also provides a critical central access point for BEIS, private and third sector, local government and public sector to collaborate. This approach can maximise the benefits across the region, driving economies of scale and accelerating routes to market for programmes that are stuck in the financing, planning or feasibility stages.

Annex I

Methodological notes and sources

Much of the modelling was undertaken by establishing baselines for future performance based upon past performance. Then applying assumptions against these baselines to understand the uplift in value that could be generated. Some sources are set out under each heading below.

Buildings

Sources used for the modelling include:

- BEIS fuel poverty statistics: www.gov.uk/government/statistics/fuel-poverty-detailed-tables-2021

- MHCLG Dwelling Stock Statistics: www.gov.uk/government/statistical-data-sets/live-tables-on-dwelling-stock-including-vacants

- ONS EPC Data: www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/housing/articles/energyefficiencyofhousinginenglandandwales/2020-09-23

The heat pumps calculation is based upon heat pump deployment expected by the CCC,[64] with the increase based upon assumptions of the size of the market support provided by government intervention in supporting the solar PV market. While the scale of the impact may vary in practice, this does illustrate the significant role that public funding can play in growing and maturing markets.

Transport

- For public transport calculations the baseline against which change was judged applied the growth rate in vehicle km from 1993 to 2019 to the years to 2050 (the year 2020 was excluded given the exceptional nature of the pandemic). The assumptions used against this baseline for a reduction in vehicle km were taken from the Climate Change Committee’s assumptions to apply low, medium and high scenarios. The source for the baseline data was DfT road traffic statistics, Table TRA 8906, www.gov.uk/government/statistical-data-sets/road-traffic-statistics-tra#traffic-volume-in-kilometres-tra02

- For active travel calculations, the baseline was trip volumes per person per year taken from the DfT data set Table NTS9903 (www.gov.uk/government/statistical-data-sets/nts01-average-number-of-trips-made-and-distance-travelled). The assumptions used against this baseline for a reduction in vehicle km were taken from the Climate Change Committee’s assumptions to apply low, medium and high scenarios.

Energy

Two data sources used for the analysis were:

- For heat network analysis: BEIS experimental statistics on heat networks - https://data.gov.uk/dataset/2f86f969-2036-4564-b690-2cd361cc8983/heat-networks-dataset

For renewables analysis: BEIS regional renewable statistics - www.gov.uk/government/statistics/regional-renewable-statistics

Endnotes

[1]The CCC, December 2020, The role of business in delivering the net zero transition, www.theccc.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/The-role-of-business-in-delivering-the-UKs-Net-Zero-ambition.pdf

[2] Climate Change Committee, 2020. Local Authorities and the Sixth Carbon Budget. Available from: www.theccc.org.uk/publication/local-authorities-and-the-sixth-carbon-budget/

[3] HNIP, Delivering financial support for heat networks, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/748477/hnip-launch.pdf

[4] Climate Change Committee, 2020. Local Authorities and the Sixth Carbon Budget. Available from: www.theccc.org.uk/publication/local-authorities-and-the-sixth-carbon-budget/

[5] Climate Change Committee, 2020. Local Authorities and the Sixth Carbon Budget. Available from: www.theccc.org.uk/publication/local-authorities-and-the-sixth-carbon-budget/

[6] Quantum Strategy & Technology Ltd for UK100, 2021. Power Shift: Research into Local Authority powers relating to climate action. Available from: www.uk100.org/sites/default/files/publications/Power_Shift.pdf

[7] Inkcap Journal, 2021. One quarter of English councils have plans to rewild. Does yours? Available from: www.inkcapjournal.co.uk/council-rewilding-england/

[8] Place-Based Climate Action Network, 2021. Trends In Local Climate Action in the UK. Available from: https://pcancities.org.uk/sites/default/files/TRENDS%20IN%20LOCAL%20CLIMATE%20ACTION%20IN%20THE%20UK%20_FINAL_0.pdf

Cornwall Council, Solar panels and planning permission. Available from: www.cornwall.gov.uk/planning-and-building-control/planning-advice-and-guidance/solar-panels-and-planning-permission/

[9] Nottingham City Council, 2020. Carbon Neutral Nottingham. Available from: www.nottinghamcity.gov.uk/media/2619917/2028-carbon-neutral-action-plan-v2-160620.pdf

[10] Energy Systems Catapult, 2018. Local Area Energy Planning in Newcastle, Manchester and Bridgend. Available from: https://es.catapult.org.uk/case-studies/local-area-energy-planning/

[11] Climate Change Committee, 2020. Local Authorities and the Sixth Carbon Budget. Available from: www.theccc.org.uk/publication/local-authorities-and-the-sixth-carbon-budget/

[12] Quantum, 2021. Power Shift: Research into Local Authority powers relating to climate action. Available from: www.uk100.org/sites/default/files/publications/Power_Shift.pdf

[13] Essex County Council, 2021. Net Zero: Making Essex Carbon Neutral. Available from: www.essex.gov.uk/climate-action

[14] Plymouth Council. District Energy. Available from: www.plymouth.gov.uk/climateemergency/projects/districtenergy

[15] London Waste and Recycling Board, 2021. London Waste and Recycling Board Response to the Draft London Food Strategy. Available from: https://relondon.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/LWARB-Response-to-the-Draft-London-Food-Strategy.pdf

[16] Ibid

[17] Ibid

[18] Place-Based Climate Action Network, 2021. Trends In Local Climate Action in the UK. Available from: https://pcancities.org.uk/sites/default/files/TRENDS%20IN%20LOCAL%20CLIMATE%20ACTION%20IN%20THE%20UK%20_FINAL_0.pdf

[19] BEIS, February 2021, Sustainable Warmth, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/960200/CCS207_CCS0221018682-001_CP_391_Sustainable_Warmth_Print.pdf

[20] LGA, Tackling Fuel Poverty Through Local Leadership, July 2013, www.local.gov.uk/sites/default/files/documents/tackling-fuel-poverty-thr-008.pdf

[21] Parliamentary Library, July 2020, Energy Company Obligation, https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/CBP-8964/CBP-8964.pdf

[22] BEIS Committee, June 2019, Building Towards Net Zero, https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201719/cmselect/cmbeis/1730/1730.pdf

[23] Centre for Sustainable Energy, June 2007, Mobilising individual behavioural change through community initiatives: Lessons for tacking climate change, www.cse.org.uk/downloads/reports-and-publications/community-energy/behaviour-change/mobilising-individual-behavioural-change-through-community-summary.pdf

[24] BEIS, May 2021, International review of domestic retrofit supply chains, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/987411/international-review-domestic-retrofit-supply-chains.pdf

[25] BEIS, Sustainable Warmth: Protecting vulnerable households, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/960200/CCS207_CCS0221018682-001_CP_391_Sustainable_Warmth_Print.pdf

[26] MHCLG, March 2021, Dwelling stock statistics, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/987564/Dwelling_Stock_Estimates_31_March_2020_Release.pdf

[27] BEIS, Sustainable Warmth: Protecting vulnerable households, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/960200/CCS207_CCS0221018682-001_CP_391_Sustainable_Warmth_Print.pdf

[28] Environmental Audit Committee, May 2021, Energy Efficiency of Existing Homes, https://committees.parliament.uk/publications/5810/documents/66321/default/

[29] Climate Change Committee, December 2020, Data and Tables, www.theccc.org.uk/publication/sixth-carbon-budget/

[30] Ibid

[31] Climate Change Committee, December 2020, www.theccc.org.uk/publication/sixth-carbon-budget/

[32] DfT, March 2021, HS2 six-monthly report to Parliament, www.gov.uk/government/speeches/hs2-6-monthly-report-to-parliament-march-2021

[33] UK Government, October 2017, Clean Growth Strategy, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/700496/clean-growth-strategy-correction-april-2018.pdf

[34] MHCLG, English Housing Survey Energy Report, 2019-20, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1000108/EHS_19-20_Energy_report.pdf

[35] HM Government, 2020. Powering our net zero future. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/945899/201216_BEIS_EWP_Command_Paper_Accessible.pdf

[36] CITB, March 2021, Building Skills for Net Zero, www.citb.co.uk/media/vnfoegub/b06414_net_zero_report_v12.pdf

[37] PHE, September 2014, Fuel Poverty and cold related health problems, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/357409/Review7_Fuel_poverty_health_inequalities.pdf

[38] WPI Economics assessment of ONS ASHE SOC data, December 2020, https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/earningsandworkinghours/datasets/regionbyoccupation4digitsoc2010ashetable15

[39] UK Parliament. Achieving net zero. Available from: https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm5801/cmselect/cmenvaud/346/34605.htm

[40] Climate Change Committee, December 2020, Surface transport, www.theccc.org.uk/publication/sixth-carbon-budget/

[41] Ibid

[42] DfT, Gear Change, June 2020, www.gov.uk/government/publications/cycling-and-walking-plan-for-england

[43] Parliamentary Question, June 2021, Electric Vehicles: Charging Points, https://questions-statements.parliament.uk/written-questions/detail/2021-06-28/23093

[44] Department for Transport, 2021. Transport decarbonisation plan. Available from : www.gov.uk/government/publications/transport-decarbonisation-plan

[45] LGA, January 2021, The future of public transport and the role of local government, www.local.gov.uk/systra-lga-bus-report#enablers-for-the-delivery-of-local-authority-ambitions

[46] DfT, February 2020, Cycling and Walking Investment Strategy, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/936926/cycling-and-walking-investment-strategy-report-to-parliament-document.pdf

[47] Sources taken from https://www.cyclinguk.org/news/how-much-are-local-authorities-really-spending-cycling-and-walking and www.aviewfromthecyclepath.com/2010/05/487-million-euros-for-cycling.html

[48] Assumption of this is taken from the Government’s Cycling and Walking Investment Strategy Report to Parliament – Moving Britain Ahead, February 2020, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/936926/cycling-and-walking-investment-strategy-report-to-parliament-document.pdf

[49] LGA, making the case for electric vehicle investment, https://local.gov.uk/sites/default/files/documents/Councils%20in%20charge%20making%20the%20case%20for%20electric%20charging%20investment%20WEB.pdf

[50] Transport for Greater Manchester. Available from: https://assets.ctfassets.net/nv7y93idf4jq/Ykfjd8IKMCe4cYuyy2i6y/89f015d16abcfb2595630ceb1be9d99e/14-1882_GM_Transport_Vision_2040.pdf

[51] LGA, 2017. Funding certainty for Greater Manchester – Transport for Greater Manchester. Available from: www.local.gov.uk/case-studies/funding-certainty-greater-manchester-transport-greater-manchester

[52] Greater Manchester Transport Committee, 2020. Walking and Cycling Update and forward look report. Available from: https://democracy.greatermanchester-ca.gov.uk/documents/s9870/GMTC%2020201009%20Walking%20and%20Cycling%20Update%20and%20forward%20look.pdf

[53] Climate Change Committee, 2020. Sixth Carbon Budget. Electricity Generation. Available from: www.theccc.org.uk/publication/sixth-carbon-budget/ [Accessed 12/07/2021].

[54] Energy Systems Catapult, December 2018, Local Area Energy Planning in Newcastle, Manchester and Bridgend, Local Area Energy Planning in Newcastle, Manchester and Bridgend - Energy Systems Catapult

[55] Oldham Council, 2017. Community Energy - ‘Generation Oldham’. Available from: https://committees.oldham.gov.uk/documents/s52200/Cabinet%2017_11_14%20-%20Community%20Energy%20-%20Appendix%201.pdf

[56] Waltham forest website, www.walthamforest.gov.uk/content/community-led-initiative-help-waltham-forest-council-residents-boost-local-renewable-energy

[57] Accolade Wines website, www.accoladewines.com/accolade-park-installs-wind-turbine-in-uk-business-first/

[58] Climate Change Committee, 2020. Sixth Carbon Budget. Electricity Generation. Available from: www.theccc.org.uk/publication/sixth-carbon-budget/

[59] The Association of Decentralised Energy, January 2018, Heat Networks in the UK, www.theade.co.uk/assets/docs/resources/Heat%20Networks%20in%20the%20UK_v5%20web%20single%20pages.pdf

[60] BEIS Heat Networks Page, www.gov.uk/guidance/heat-networks-overview

[61] Ibid

[62] South West Energy Hub. The South West Energy Hub. Available from: www.westofengland-ca.gov.uk/south-west-energy-hub/

[63] Heart of the South West – Local Enterprise Partnership. LEPs agree to make energy and clean energy a priority for the South West. Available from: https://heartofswlep.co.uk/news/leps-agree-make-energy-clean-energy-priority-south-west/

[l64] Calculation taken from BEIS, UK Energy in brief, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/904503/UK_Energy_in_Brief_2020.pdf