Introduction

It recognises that while sometimes hospital is the most appropriate place for someone to be, most people want to be at home and independent for as long possible, and that this is generally the best place for them to recover.

A preventable admission is one where there was scope for earlier, or different, action to prevent an individual’s health or social circumstances from deteriorating to the extent where hospital or long-term bed-based residential or nursing care is required. This tool identifies actions and interventions which will enable systems to understand their populations, identify those most at-risk of a preventable admission and take action to engage individuals and target support to improve their health and wellbeing.

Who is most at risk of a preventable admission?

Research commissioned by the LGA found in 2016:

In over a quarter (26 per cent) of cases reviewed where people had been admitted to an acute hospital, there had been missed opportunities to make interventions that would have avoided the need for admission.”

High rates of emergency hospital admissions of people with conditions that are considered to be amenable to prompt, person-centred care in the community, suggest the need for more co-ordinated care.

The Nuffield Trust has shown:

“In 2019/20, nine in every 1,000 people in England were admitted to hospital in an emergency with an ambulatory care sensitive condition and 25 in every 1,000 people were admitted with an urgent care sensitive condition. This is surprisingly high given that these are potentially preventable causes of emergency admission.”

There are many different labels that are used to categorise people at risk of a preventable admission and the statistics can hide the richness, challenges, and complexity in their lives. The COVID-19 pandemic has both increased awareness of, and exacerbated, the risks that health and wider inequalities, including deprivation, can pose to health and wellbeing, and how these risks can overlap and compound their impact. Being frail, for example, does not preclude anyone from also having any number of long-term health conditions, mental ill-health, or from experiencing the impact of inequalities.

How to use this resource

System leaders and staff from across local government, the NHS, the voluntary, community and social enterprise sector, and service user and carers groups all have a part to play in working together to improve health and wellbeing, and deliver person-centred care in the most appropriate setting.

By working together, partners can pool and build on their collective local knowledge and expertise to identify and take a strength- and asset-based approach to understanding and addressing preventable admissions in their area.

Local partners should take from this document what is most relevant and appropriate for their context, acknowledging that not all the interventions outlined here will be appropriate for all individuals and in all circumstances.

The Care and Health Improvement Programme’s Integration support offer can support local systems with these conversations.

Why now?

- Intervening proactively with lower-intensity support can help to delay or reduce someone’s need for more care in the future and help them retain their independence, health, and wellbeing for longer.

- The incidence of preventable admissions is a strong indicator of both the local social, demographic, and economic environment and the degree of system cohesion in supporting person-centred and coordinated care, support, treatment and safeguards.

- Unplanned admissions, whether to hospital or a care home, can be distressing experiences for individuals and their families, and expensive in terms of resource use for the health and care system. They can create uncertainty for those responsible for planning and delivering services.

- Significant savings are possible by reducing avoidable admissions to bed-based care (Shifting the balance of care: great expectations). Research routinely demonstrates that people are over-prescribed care, which is above their care needs, reducing their independence and tying up resources in the provision of unnecessary care (Efficiency opportunities through health and social care integration: delivering more sustainable health and care).

- Those with ambulatory care sensitive conditions account for a significant proportion of avoidable admissions that could have been prevented with timely detection and intervention in the community (Reducing avoidable emergency admissions. Analysis of the impact of ambulatory care sensitive conditions in England. Dr Foster).

- Identifying those people who have a greater level of frailty can help avoid these events happening; such identifying those who have a higher risk of falls, self-neglect, carer breakdown, infections leading to delirium, hospital admissions or admission to long-term bed-based care.

- Those who experience health, social and/or economic inequalities have an increased risk of preventable admissions and the compounding effects of overlapping inequalities.

- The COVID-19 pandemic has required partners to develop a joint response which has in turn highlighted the importance of reducing preventable admissions and the role of community-based services in achieving this.

Policy context

This High Impact Change Model to Reduce Preventable Admissions is informed by:

- The Care Act’s vision that “the care and support system works to actively promote wellbeing and independence, and does not just wait to respond when people reach a crisis point”.

- Shifting the Centre of Gravity which shows how a model of person-centred, place-based integrated care and support can successfully improve people’s health and wellbeing, including reducing the need for unplanned hospital admissions and long-term residential care.

- How the Better Care Fund supports many areas to join health and care services through implementing integrated local models of health and care that aim to enable people to manage better their own health and wellbeing, and live in their communities for as long as possible.

- The Home First ethos and the Hospital Discharge Service: Policy and Operating Model which encourages wraparound care at home to aid recovery and sustain independence at home for longer .

- The NHS Long Term Plan and the NHS 2021/22 priorities and planning guidance which include, for example, population health management, anticipatory care, urgent community response and recovery of elective activity

- Requests to focus on this area, which were made during the 2019 review of the ‘High Impact Change Model: Managing Transfers of Care between Hospital and Home’.

- The COVID-19 pandemic, which has also shown:

- systems have immense ability to overcome barriers and shift resources for timely response

- that there is an appetite and impatience for faster and sustainable change

- an increased national focus and attention on a system that was already under intense pressure

- an adverse impact on those who were already experiencing inequalities

- the importance of having an adaptable and sufficient workforce with parity between health and social care

- removing the financial barriers can lead to effective discharge to assess practice

- a reluctance of individuals to visit A&E

- because of its impact, such as on mental health or for those with long COVID for example, it is generating a need for certain services.

Principles

There is a platform of eight overarching principles that underpin this model and its implementation:

1. Commitment and focus to support people to remain in their homes, or usual place of residence, when they are having a health or social care crisis, preventing admission to hospital or long-term care where possible AND then supporting them to maintain or regain skills, confidence and independence.

2. Transferring power and knowledge to individuals and communities so they can take ownership of their health and wellbeing.

3. “Right care, right time, right place.”

4. The workforce understands the community it serves and places the individual at the centre.

5. Inclusive, person-centred, strength-based partnerships with communities and individuals provide the foundation for reducing preventable admissions.

6. Do it at scale: support planning, infrastructure, delivery, and person-centred practice with, and across, individuals, neighbourhood, place, and system levels.

7. Health and wider inequalities, as well as their compounding effects, must be considered and addressed in every high impact change.

8. Focus on what works using research, emerging and established evidence and lessons learned.

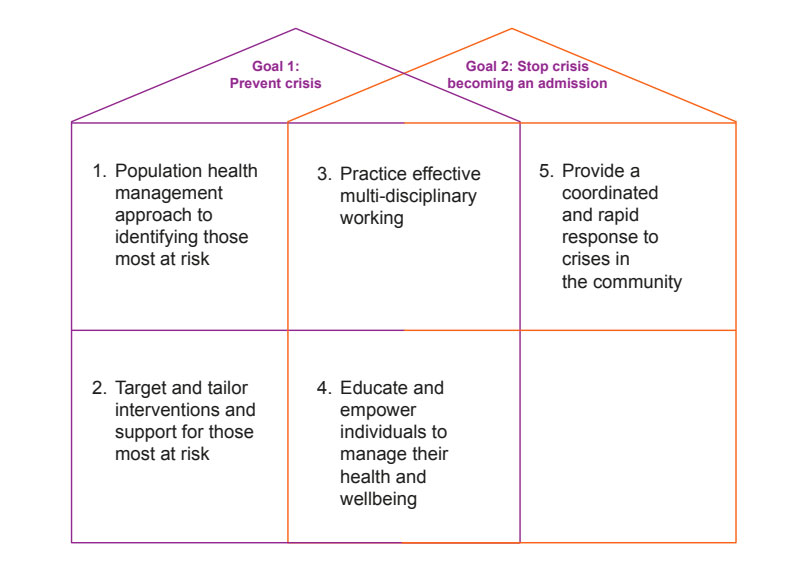

The High Impact Change Model: Reducing Preventable Admissions

There are many different interventions and services that can contribute to preventing crises developing or stop them escalating, and in some cases both.

Here are some examples to illustrate the model; this is not an exhaustive list but one designed to prompt conversations about how local interventions and services can contribute to these two goals.

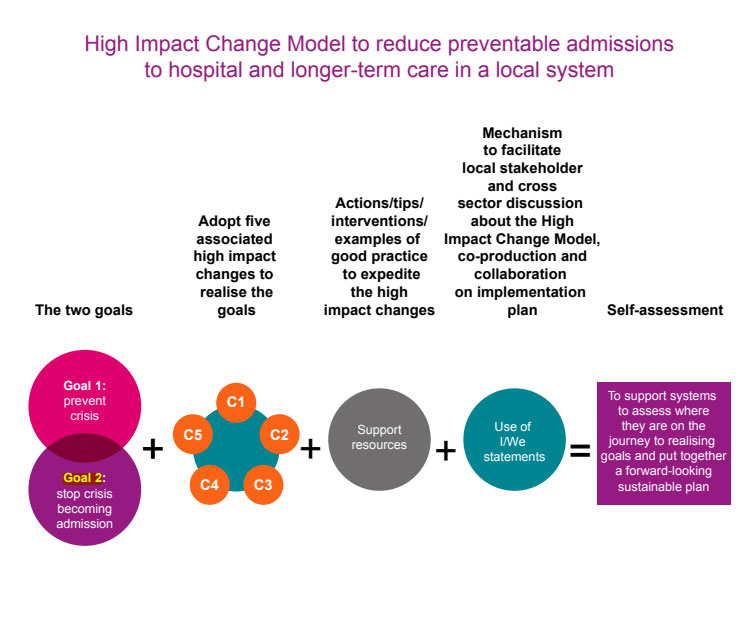

The 2 Goals Explained

The model focuses on two goals and five high impact changes that help realise one or both goals. For each of the high impact changes, the model includes tips, case studies and links to further information, as described in this diagram. The Care and Health Improvement Programme’s Integration support offer [https:// www.local.gov.uk/our-support/our-improvement-offer/care-and-health-improvement/ integration-and-better-care-fund] can support local systems with these conversations. Preventable admissions are those where there was scope for earlier, or different, action to prevent an individual’s health deteriorating to the extent where hospital or l

1. Population health management approach to identifying those most at risk. 2. Target and tailor interventions and support for those most at risk. 3. Practice effective multi disciplinary working. 4. Educate and empower individuals to manage their health and wellbeing. 5. Provide a coordinated and rapid response to crises in the community.

For each of the high impact changes, the model includes tips, case studies and links to further information, as described in this diagram. The Care and Health Improvement Programme’s Integration support offer can support local systems with these conversations.

Making It Real: framework

Providing personalised care and support is central to providing the right care in the right place and reducing preventable admissions.

The framework is based on the following principles and values of personalisation and community-based support:

- People are citizens first and foremost.

- A sense of belonging, positive relationships and contributing to community life are important to people’s health and wellbeing.

- Conversations with people are based on what matters most to them. Support is built around people’s strengths, their own networks of support, and resources (assets) that can be mobilised from the local community.

- People are at the centre. Support is available to enable people to have as much choice and control over their care and support as they wish.

- Co-production is key. People are involved as equal partners in designing their own care and support.

- People are treated equally and fairly, and the diversity of individuals and their communities should be recognised and viewed as a strength.

- Feedback from people on their experience and outcomes is routinely sought and used.

Change 1: Population health management approach to identifying those most at risk

Collaborate with local partners to bring together data and insight to form an integrated view of those at high risk of preventable admissions

Making it Real statements

I am supported by people who listen carefully, so they know what matters to me and how to support me to live the life I want."

We know how to have conversations with people that explore what matters most to them – how they can achieve their goals, where and how they live, and how they can manage their health, keep safe and be part of the local community."

Tips for success

- Ensure there is a clear understanding and agreement across all partners, from the start, of what datasets are available across the system relevant to preventable hospital and long-term care admissions and how they will be used for the analysis.

- Align datasets to identify those who are frequent users of urgent and emergency care or are at risk of bed-based care. These may include people with ambulatory care sensitive conditions, urgent care sensitive conditions, increasing frailty, those with multiple long term conditions, or who are particularly socially isolated.

- Use population health assessments or joint strategic needs assessments to understand which population groups are at risk of preventable admissions, drawing on the existing knowledge and strength of partners. This analysis may include demographic patterns, health and wider inequalities, people’s lived experience, admissions data, trends, service use, provider data, gap analysis, care quality assessment, benchmarking, challenges, and recommendations. Use population segmentation tools and techniques to identify and understand the needs of local population groups. Triangulate quantitative data with qualitative data, such as care teams’ views, feedback from staff or local Healthwatch.

-

Assess the effects of health and wider inequalities, and the impact of local levels of deprivation, on the rate of preventable admissions.

-

With partners, agree a system-wide interpretation of the combined data and insight so there is common understanding of local trends and each partner can model risk as they address the common agreed actions. Individual partners can use this agreed interpretation as a guide, giving them flexibility to tailor their own contribution to reducing preventable admissions.

-

Risk stratification should be a dynamic process. Risk levels should be re-evaluated and adjusted regularly.

Examples of emerging and developing practice

- Advancing population health management: stories from 10 areas about their different experiences of using Population Health Management, NHS Clinical Commissioners, February 2020.

- Using data mapping to inform care decisions: ‘The Bridge’ is a data visualisation tool, designed to display public sector data and provide effective economic forecasting and market insights to inform commissioning decisions, strengthen local care provider markets and inform the development of future strategy. LGA, March 2021.

- Improving population health on the frontline – a patient’s view, A short video about a couple with type 2 diabetes who have seen benefits to their health after professionals in the Berkshire West Integrated Care System used a Population Health Management (PHM) approach to understand their issues and offer them more personalised care options, January 2020.

Supporting materials

- An introduction to population health management, NHS Confederation PCN Network, 2020

- Disparities in the risk and outcomes of COVID-19, Public Health England, 2020

- Reducing avoidable emergency admissions, analysis of the impact of ambulatory care sensitive conditions in England, Dr Foster, 2019

- Population segmentation tools: ‘How to’ Guide: The BCF Technical Toolkit, Section 1, Better Care Fund, August 2014

- Risk stratification tools; for guidance and Top Tips on using risk stratification see Annex A, NHS England, June 2014

- Ambulatory Care Sensitive Conditions: Analysis of certain conditions for which unplanned hospitalisation may be prevented or reduced by provision of care in primary or community settings. NHS Digital, September 2020

- What are health inequalities? The King’s Fund, February 2020

- Health Inequality and the A&E Crisis, Centre for Health Economics, January 2016

- Homelessness: applying All Our Health, Public Health England, guide for front-line health and care staff to take action on homelessness, June 2019.

Change 2: Target and tailor interventions and support for those most at risk

Address the most pressing clinical and social barriers, identified by data and insight, that put people at risk of a preventable admission through dedicated services.

Making it Real statements

I feel safe and am supported to understand and manage any risks."

We work with people to manage risks by thinking creatively about options for safe solutions that enable people to do things that matter to them."

Tips for success

-

Having formed an integrated view of those at high risk of preventable admissions, maintain and use local lists and registers of at-risk cohorts to offer regular timely screenings and interventions. Take account of when seasonal or time-based responses may be needed, such as ‘flu or months when falls-related admissions increase.

-

Make the use of screening tools, such as the Frailty Index, part of the pathway used to identify individuals at risk. Support more integrated care for people living with frailty by developing enriched summary care records.

-

Provide a single point of access for health and care staff to make referrals for community interventions. Where possible these should be trusted referrals which lead straight to intervention, to avoid the person repeating their situation and so that they can be coordinated around the individual and their family and/or carer(s).

-

Ensure collaboration between pharmacists and other community services to support medicine reconciliation and review.

-

Early use of technological interventions and solutions, where appropriate, can promote independence for longer and so delay or remove the need for community services, such as homecare, altogether. Develop a process to introduce assistive living equipment and digital tools to support self-management as soon as possible after the need is identified.

-

Use telehealth and telecare to support the treatment and monitoring of people at home to anticipate potential problems or crises. Embed the use of digital technology, where appropriate, such as remote monitoring and video consultations, across the pathway from home to hospital or care home, and then the transition back to community.

-

Ensure that housing needs are considered. Ready access to an appropriate range of housing related support can help people stay in their own home as well as support those with no or inappropriate housing.

-

The NHS Enhanced Healthcare in Care Homes framework sets out the key actions to support health and wellbeing for care home residents.

-

Where telecare is used as a reablement intervention, consider expanding this offer to include other types of telehealth digital monitoring devices. Use trusted assessment to prevent delays in assessment. Reablement can be used as a preventative intervention.

-

Unlocking the preventative benefits of care technology requires a good understanding of the digital and data capabilities of your local care technology offer. What is your approach to using data from devices to drive real-time decision making or to anticipate and prevent crises? How will the data collected from technology be analysed and used to inform care planning and reviews or reassessments?

-

Ensure that care plans for those at the highest risk include regular prompts for timely screenings and other forms of preventive care. Consider also whether a safeguarding plan is required.

Examples of emerging and developing practice

- Following two avoidable deaths of people with learning disabilities Camden introduced a population health management approach to avoiding physical health hospital admissions for people with learning disabilities. This led to the implementation of ‘Significant 7+’ which has increased the confidence of supported living provider staff to take early action including saving a life through early identification of sepsis and reducing 999 calls. LGA, April 2021

- ‘How (I try!) to avoid a hospital admission for someone with frailty’, A blog from a community geriatric team doctor working in West Kent’s Home Treatment Service, British Geriatric Society, March 2018

- Increasing uptake of assistive technology through behavioural insights: Knowsley Metropolitan Borough Council increased the use of assistive technology in the home by targeting groups of residents who might benefit – those with blue badges and those with assisted bin collections, LGA February 2019

- Health Call Digital Care Home: Durham has taken a partnership approach to rolling out technology, including remote monitoring across older people care homes, extra care and two specialist learning disabilities homes, which has contributed to a reduction of two hospital admissions per care home per month, LGA, June 2020.

- Meeting the home adaptation needs of older people, Is your council actively addressing residents' need for help with home adaptations?, LGA, March 2020.

- NHS Quick Guide: Health and Housing, Provides tips and case studies to support health and care systems, 2016.

- Adaptations without delay, A guide to planning and delivering home adaptations differently, Royal College of Occupational Therapists, 2019.

- Help with home adaptations: improving local services, A ‘Home Adaptation Challenge Checklist’ for older people’s forums and other stakeholders, Care and Repair, 2019.

- NHS Frailty resources Including the NHS Rightcare Frailty Toolkit, June 2019.

- Healthcare Improvement Scotland’s webpages: What is Anticipatory Planning Toolkit to help planning for the future.

- Safeguarding resources, LGA and ADASS Safeguarding Network web page.

- Transforming out-of-hospital care for people who are homeless, Support Tool & Briefing Notes complementing the High Impact Change Model for transfers between hospital and home, King’s College, November 2019.

- LGA Care Technology Planning Resource, a practical tool to enable councils to review their local care technology approach in a structured way and to act as a catalyst for further activity, November 2020.

Change 3: Practise effective multi-disciplinary working

Foster trusted and joint assessments, shared decision-making and positive risk-taking to deliver pro-active person-centred care. Working together with individuals, and their family and/or carers can build confidence and facilitate a holistic approach to meeting needs.

Making it Real statements

I have care and support that is coordinated, and everyone works well together and with me."

We work with people as equal partners and combine our respective knowledge and experience to support joint decision-making."

Tips for success

-

Work out who needs to be involved in delivering holistic, person-centred and coordinated care and support in each locality. Working with independent, voluntary, community and social enterprise organisations is important, including for people who are funding their own care.

-

Adapt the membership of your multi-disciplinary team (MDT) according to the care and support needs of your local population and individuals with whom you work. Consider collaborating with wider professionals and care givers such as mental health practitioners, pharmacists, carers, dietitians, housing representatives (such as housing or homelessness officers or home improvement agency staff), and any other specialists who may bring expertise and coordination.

-

Successful joint assessments and care planning can prevent admissions when people and their family and/or carers are involved in, and share, the decision-making. This can be underpinned by shared care records and standardised documentation practices across the MDT and care providers.

-

Using trusted assessment principles to carry out a holistic assessment of need avoids duplication and can reduce the time someone waits to be assessed. This can be the best-placed person who is involved in the person’s care, for example social worker, community physiotherapist or crisis response team.

-

Train team members to identify how health and wider inequalities’ impact on population groups, individuals, and their carers to find solutions that help to mitigate their risk of admission.

-

Train members of MDTs in shared decision-making, strengths-based approaches and positive risk-taking so they are confident in having honest conversations with individuals, and their carers, about their options. Frontline staff should feel comfortable discussing options, risks, and benefits with individuals to weigh up their preferences and capabilities for self-management.

-

Meeting regularly in a ‘huddle’ can help multi-disciplinary colleagues to plan proactively the care of people with more complex needs to reduce the risk of admissions.

-

Provide training, forums or peer-learning meetings that support dialogue and reflections among different roles involved in admission avoidance to foster trust and an open culture within MDTs.

-

Develop and maintain close joint working with local welfare and benefits advice, housing information and advice services so that staff can help people find and use up-to-date sources, including local directories.

-

Link services’ regular monitoring of individuals who are at risk of an emergency admission including those who have intensive or complex care packages, frequent health crises and GP call outs, and multiple outpatient appointments or are near the end of their life.

-

Regularly review how effectively people are handed between services and work collaboratively to improve processes along the whole admissions avoidance pathway.

-

Focus on using proactive case management approaches and support to provide home-based care rather than secondary care.

-

End of life care, including advance care planning must always be personalised [Adult social care: our COVID-19 winter plan 2020 to 2021, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/adult-social-care-coronavirus-covid-19-winter-plan-2020-to-2021/adult-social-care-our-covid-19-winter-plan-2020-to-2021]. The individual must be the decision-maker for their care at the end of their life, supported by informed discussions with their MDTs. Hospice at home models and community specialist palliative care teams, some of whom operate through hubs which are set up to respond to crisis situations, can make an important contribution to care at home and reduce preventable admissions.

-

Consider moving towards a transdisciplinary model where one discipline may take on the traditional function of another by agreement.

Examples of emerging and developing practice

- Greenwich’s Joint Emergency Team (JET) provides integrated care using multi-disciplinary and trans-disciplinary team approaches to prevent unnecessary hospital admissions in Accident & Emergency, the Acute Medical Unit and the community, British Journal of Research, October 2019.

- Barnsley Council: collaborative working with the voluntary and community sector to improve individual experiences at the end of life, A Macmillan social worker is part of the MDT providing expert support for people in need of complex palliative care and support at the end of their life in Barnsley, LGA September 2020.

- Gateshead and Newcastle’s Falls Rapid Response Service is crewed by a paramedic and occupational therapist who reduce response times by taking referrals direct from 999/111 for people aged over 60 who have had a fall in their own home. The service can arrange onward referral to prevent future falls, January 2020.

Supporting materials

- Making it happen: Multi-disciplinary (MDT) team working, NHS England, January 2015.

- Positive risk taking, Joseph Rowntree Foundation, 2014.

- Quick guides to support health and social care systems, NHS website.

- Enhanced Health in Care Homes NHS England Improvement, March 2020.

- End of life care: guide for councils, LGA/ADASS, September 2020.

- Ambitions for Palliative and End of Life Care: A national framework for local action 2015-2020.

- Making decisions on the duty to carry out Safeguarding enquiries, Making Safeguarding Personal, ADASS and LGA, August 2019.

Change 4: Educate and empower individuals to manage their health and wellbeing

Facilitate sustainable interventions and support that enable individuals, and their carers, to confidently manage their own health and wellbeing, and maintain their independence at home or their usual place of residence.

Making it Real statements

I am in control of planning my care and support. If I need help with this, people who know and care about me are involved."

We work with people as equal partners and combine our respective knowledge and experience to support joint decision-making."

Tips for success

-

Peer support and health coaching interventions have been found to be effective in helping to develop coping mechanisms. Health and social care commissioners should consider aligning or jointly commissioning.

-

Train and support staff to promote self-management as part of their routine practice and to trust people’s ability to manage their health and wellbeing. Be proactive in checking on individuals and their carers so they continue to feel supported to self-manage and know what to do if their condition changes. Use technology to support self-management and promote independence where appropriate.

-

Train frontline staff in communication techniques, such as motivational interviewing and patient activation, that engage people in honest conversations about their health and wellbeing. Be clear about the responsibilities that their health and social care teams hold for providing their care.

-

Consider using a self-management measurement tool to evaluate individuals’ knowledge, confidence, and skills to manage their own health conditions in order to personalise interventions, support and strength-based conversations.

-

Work with unpaid carers to identify and address their needs so that they can continue to care. A breakdown in care can increase the risk of an unplanned or prolonged admission to hospital or care home.

-

Help individuals access appropriate equipment and adaptations to make their home environment more suitable for managing their condition.

-

Support those with complex conditions to be able to navigate their care networks efficiently, particularly when they receive care from multiple places.

-

Personal assistants can enable people to be more independent and in control of their lives. Promote these benefits by providing advice and guidance about employing personal assistants to people, their families, and those who work with them. Consider creating support structures to facilitate informed decisions.

-

Compassionate and timely advanced care planning can help people to plan and anticipate how to meet their current and future care needs.

-

Encourage early conversations about advanced care planning, to be able to uphold people’s wishes should they have diminishing capacity, be receiving palliative care or are at the end of their life.

-

Ensure information and advice is available to help everyone regardless of their circumstances. This includes self-funders, to help them make informed choices about their care and how they will pay for it.

-

Provide a range of accessible resources to educate people and their family and/or carers to understand and manage their medicines.

-

Ensure timely translation of key messages and materials into the languages and formats that people can understand. Collaborate with partners, local community groups and networks to identify and engage community influencers, whom people trust, to deliver these messages, such as community leaders, religious leaders, or health or care workers.

-

Promote health literacy by assisting individuals and their family and/or carers to accessible information and advice resources, both online and offline, that will help them manage their health conditions. Where appropriate, expand this offer to include digital self-management tools, educational interventions and one-to-one support that is tailored to the needs of the local population. Reducing digital exclusion, as well as social exclusion and associated health inequalities, will help more people to feel confident to use these tools.

-

Provide opportunities to share and learn from others. Connect people to local support groups and informal networks that will help build their confidence and resilience.

-

Invest in building capacity and confidence for self-management by digital means. Understand how well connected your target group is and address the barriers some people face in using digital tools.

-

Allocate resources to reaching people who might be receptive to managing their health conditions and building their support networks through national initiatives such as Self Care Week (15-21 November 2021).

Examples of emerging and developing practice

-

“A Digital Health Hub is a trusted place, with trusted people accessing trusted information.” 100% Leeds Digital partnered with Cross Gates & District Good Neighbours scheme to launch a digital health hub in 2019 which has since supported people through lockdown.

-

The Central and North West London Recovery and Wellbeing College provides educational courses, workshops and resources to people with mental health difficulties, their families, supporters and carers, and staff to give them the skills and confidence to manage their mental health, physical health and wellbeing and aim to promote recovery and social inclusion.

-

Isle of Wight: Personal Assistant Hospital Discharge Initiative and PA Hub: The council has worked with partners to establish a personal assistant market that supports residents in their own homes and reduces avoidable admissions to care homes. LGA, December 2020.

-

Huntingdonshire District Council: getting cancer and cardiac rehab patients active with self-care: case study about supporting good rehabilitation and self-care, LGA November 2018.

-

Since it started to use the House of Care model to support people to self-manage their conditions, Leeds has continued to embed its person centred approach by providing training on collaborative care and support planning through ‘Better Conversations’ and its’ ‘Supporting people through kind conversations’ elearning package.

Supporting materials

- Carers UK's advice on planning for emergencies, December 2020.

- Communities who are prepared to help, Hospice UK’s toolkit, July 2019.

- Digital Motivation: Motivational barriers of non-users of the internet , Good Things Foundation, February 2019.

- Social prescribing, NHS webpage.

- Supported self-management, NHS webpage.

- Supported self-management summary guide, NHS England and NHS Improvement, March 2020.

- Health Coaching Implementation and Quality Summary Guide, NHS England and NHS Improvement, March 2020.

- Advance Care Planning, The Gold Standards Framework, April 2018.

- Self care: councils helping people to look after themselves, LGA November 2018.

Change 5: Provide a coordinated and rapid response to crises in the community

Establish a range of integrated services that provide a coordinated and personalised response in the community.

Making it Real statements

I can plan ahead and stay in control in emergencies. I know who to contact and how to contact them and people follow my advance wishes and decisions as much as possible."

We make sure that people, and those closest to them, know what to do and who to contact if their health condition, support arrangements or housing conditions are deteriorating, and a crisis could develop. We respond quickly to anyone raising concerns."

Tips for success

-

The NHS Planning guidance asks all systems to provide a two-hour community response covering 8am to 8pm, 7 days a week. Crisis response teams can be made up of a range of professionals such as nurses, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, paramedics, social workers and social care staff in order to provide a coordinated response. Make sure frontline staff know how to refer people to these services and also ensure the public and ambulance services can access the service via NHS111.

-

Comprehensive assessment and streaming services with triage pathways for people who attend A&E either voluntarily or through ambulance conveyance ensure that people are admitted only if clinically necessary to do so.

-

Consider commissioning local voluntary sector organisations, including housing and homelessness workers, to support individuals in A&E or at the front door to adult social care, providing an alternative to admission.

-

A carers’ emergency service can provide replacement care so that individuals being cared for are not admitted to hospital or other bed-based care due to a breakdown in informal caring arrangements.

-

Ensure a clear set of options for referral pathways between paramedics, the ambulance service and local urgent care services including rapid response. Ensure frontline staff are informed, understand, and adhere to these options.

-

Update NHS111 regularly with local crisis response arrangements and how to access them by ensuring all services are updated on the Directory of Services. Ensure appropriate data sharing processes are in place prior to crisis so that personal information, such as medications, is easily available so that an appropriate response can be provided in the community. Ensure that this information travels with individuals when they transfer between care settings.

-

Provide the workforce with the technology that enables them to communicate and collaborate with other health and care colleagues when on a call-out.

-

Reablement services can support an individual as a preventative measure for those most at risk of an admission as well as to support recovery after a hospital stay. Intensive reablement, such as live-in care or 24hour care, can be used for short periods to stabilise individuals.

-

The services and approaches described in other changes in this tool can be utilised as a crisis response, such as deploying aids, adaptations, and voluntary sector support.

-

Think creatively about alternative housing options that could prevent a crisis escalating and leading to a care home admission, such as extra care and innovative shared lives models of care. For more information, see the High Impact Change Model: Managing Transfers of Care between Hospital and Home.

Examples of emerging and developing practice

- The multi-agency REACT team (Reactive Emergency Assessment Community Team) helps prevent more than 600 admissions to Ipswich Hospital every month by making sure people receive the right treatment in their own homes.

- By providing an immediate response, primarily to people aged over 65, operating 12 hours a day, seven days a week, the East of England Ambulance Service’s Early Intervention Vehicle has reduced ambulance conveyances and unplanned hospital admissions.

- Salford Royal NHS Foundation Trust has used virtual wards to monitor the condition of COVID-positive individuals who have not required a hospital admission but are deemed to be at risk of deterioration using pulse oximetry at home. December 2020.

- Leicester Partnership NHS Trust is able to prioritise referrals requiring a 2-hour crisis or 2-day reablement response from the urgent community response teams by using Autoplanner, software built into the Electronic Patient Record. December 2020.

- Lincolnshire’s hospital avoidance response team (HART) helps avoid hospital admissions by supporting the clinical assessment service, LGA September 2019.

Supporting materials

- Urgent Treatment Centres, NHS webpage.

- Urgent community response – two-hour and two-day response standards, 2020/21 Technical data guidance, NHS England and NHS Improvement, November 2020

- Community health services two-hour crisis response standard guidance, NHS England

- Ambulatory Emergency Care Network website.

- Reducing avoidable ambulance conveyance in England: Interventions and associated evidence, The University of Sheffield, School of Health and Related Research, March 2020.

- Rapid Response Teams, NHS news item, January 2020.

- Intermediate care including reablement NICE guideline, September 2017.

- Reablement resources and updated guidance, SCIE, September 2020.

- Quick Guide: Hospital Transfer Pathway – ‘Red Bag’, DHSC/NHSEI, June 2018.

- Clinical Assessment Services, NHS Digital, November 2019.

- Shared Lives Plus website.

Self-assessment questions

Change 1 Population health management approach to identifying those most at risk

- To what extent is there a shared understanding and agreement across partners about what relevant datasets are available and how they will be used for analysis?

- To what extent do all partners have a common understanding of local trends and insights so there is a single shared truth? Does this include a shared understanding the impact of health and wider inequalities at a local level?

- How well does each partner use this agreed interpretation to model risk and tailor their own contribution to reducing preventable admissions?

Change 2 Target and tailor interventions and support for those most at risk

- To what extent do services address the most pressing clinical and social needs, as identified by data and insights?

- Is there a single point of access and how effective is it in coordinating referrals for community interventions around the individual and their family and carers?

- To what extent is there ready access to an appropriate range of services that can help prevent or avert crises?

- To what extent is digital technology used to identify and precent escalating need in people most at risk?

Change 3 Practice effective multi-disciplinary working

- How successful are multi-disciplinary teams in adapting and flexing their membership to the needs of their specific local area?

- To what extent are individuals, their families and carers routinely and meaningfully involved in joint assessments and making decisions about their care plans? Does this include planning proactively with people with more complex needs?

- How successful is training to promote a pro-active, preventative, and multi-disciplinary approach, with the right mix of skills? How do staff describe the culture?

- How well understood is the impact of multiple inequalities on individuals’ risk of preventable admissions?

Change 4 Educate and empower people to manage their own health and wellbeing

- What opportunities are available for people to build their confidence, and resilience? What information and resources are allocated to reaching people who might be receptive to managing their health conditions and building their support networks?

- How do partners work with unpaid carers to identify and address their needs so they can continue to care? What are the measures of success?

- How are staff enabled to promote self-management as part of their routine practice? How much do staff trust and build people’s ability to self-manage and support them when their condition changes?

- How accessible, timely and relevant is the information available to help people make informed choices?

- How receptive have people been to making their home and social environments more suitable? For example, using equipment, adopting technology, or joining peer or local community groups networks that can help them manage more easily?

Change 5 Provide a coordinated and rapid response to crises in the community

- To what extent are appropriate services in place for your area? Do they include reducing the risk of reoccurrence?

- How well do staff understand and use what local crisis response services are available and how to access them?

- What systems are in place to facilitate the timely sharing of information to prevent a person from having to tell their story more than once?

- To what extent are enablement and step-up services offered to those most at risk of an admission, including intensive enablement or 24-hour care?